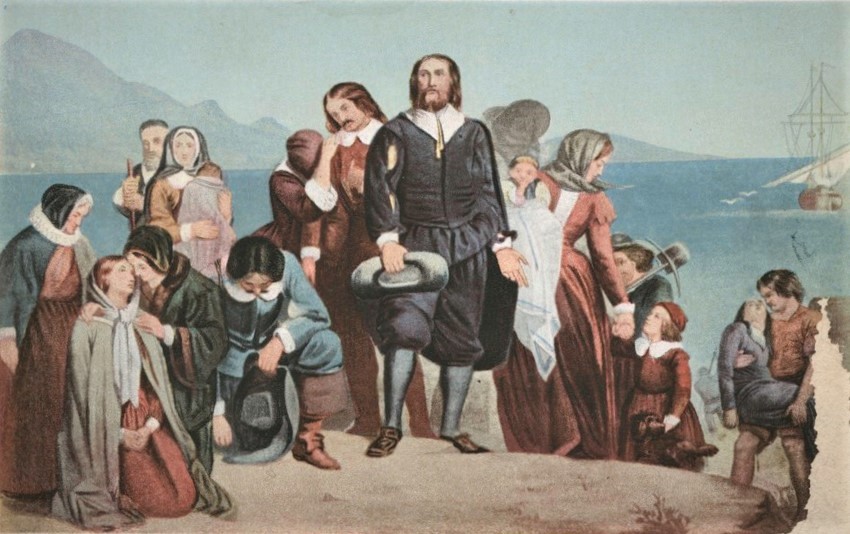

Hey there, history buffs and culture vultures! Ever scrolled through old paintings and thought, “Wow, that’s just a painting of a king, what’s the big deal?” Well, buckle up, because we’re about to take a wild ride back to the 18th century, a time when a simple royal portrait could ignite a firestorm of public debate, challenge centuries of tradition, and basically make people clutch their pearls! We’re talking about the Age of Enlightenment, a period in Europe and Western civilization from the late 17th to the 19th century that was less “polite tea party” and more “intellectual mosh pit.”

This wasn’t just about fancy wigs and powdered faces; it was a total intellectual and cultural earthquake that shattered old ways of thinking. Imagine a world where people suddenly started emphasizing reason, empirical evidence, and the scientific method over blind faith and inherited power. They promoted wild new ideals like individual liberty, religious tolerance, progress, and natural rights! Sounds like a playlist of revolutionary hits, right? These ideas weren’t just for dusty books; they seeped into every corner of life, including how people viewed their monarchs – and, consequently, how those monarchs were depicted in art. A royal portrait, once a symbol of unquestionable divine right, suddenly became a battleground of ideas.

So, how did a period defined by big brains like Voltaire and Kant, and monumental shifts like the Scientific Revolution, turn royal portraiture into something truly *shocking*? It’s all about context, baby! The Enlightenment wasn’t just a backdrop; it was the main event, creating a new public mindset that scrutinized power, questioned tradition, and demanded more than just a pretty face on canvas. Get ready to dive into the first five mind-blowing concepts that basically told the old world, “It’s time for a glow-up, or prepare for the drama!” These are the ideas that had everyone buzzing, whispering, and totally rethinking what it meant to look at a king or queen.

1. **The Ascent of Reason and Individual Liberty**Alright, first up on our “What Made Royal Portraits Spicy” list is the absolute triumph of *reason* and the burgeoning idea of *individual liberty*. Before the Enlightenment crashed the party, the world largely ran on tradition, authority, and often, the divine right of kings. But then came thinkers like René Descartes, with his famous “Cogito, ergo sum” (“I think, therefore I am”), encouraging everyone to systematically disbelieve everything unless there was a well-founded reason for accepting it. This wasn’t just a philosophy class assignment; it was a direct challenge to the idea that a monarch’s power was simply God-given and beyond question. If individuals were encouraged to think for themselves, how could they passively accept a portrait that just screamed, “I’m in charge because… well, because I am!”?

This new emphasis on reason meant that the legitimacy of power, including that depicted in a royal portrait, was now subject to rational scrutiny. No longer could a painting merely showcase opulent robes and a crown as proof of authority; the enlightened public started asking, “But *why* is this person worthy?” Furthermore, the Enlightenment vigorously promoted ideals of individual liberty. Think about it: if every person has an inherent right to freedom, how does that square with a monumental portrait of a ruler who symbolizes absolute control over subjects? The dissonance alone could be genuinely shocking, subtly undermining the very image of unquestioned sovereignty that such art was designed to project.

The “Age of Reason” wasn’t just a catchy nickname; it was a complete paradigm shift. Royal portraits, which historically functioned as propaganda for absolute power, suddenly had to contend with an audience trained to “dare to know,” as Immanuel Kant put it with his phrase “sapere aude.” A portrait that clung too closely to old, irrational assertions of power would not only fail to inspire awe but could actively provoke intellectual disdain, becoming a symbol of the very “ignorance and prejudice” that Frederick the Great, an enlightened monarch himself, sought to combat. This intellectual awakening transformed the passive viewer into an active critic, making the portrayal of royalty a far more perilous artistic venture.

Read more about: Unpacking the Legacy: 12 Pivotal Chapters in the Illustrious Life of George Washington

2. **Undermining Traditional Authority: Monarchy and Church**Next up, let’s talk about the ultimate mic drop of the Enlightenment: its relentless drive to *undermine the authority of the monarchy and religious officials*. Imagine a world where your rulers and religious leaders are the unquestionable top dogs, and then suddenly, a whole intellectual movement starts poking holes in their divine armor. This movement paved the way for the political revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries, but even before the guillotines, it was shaking up public perception in a huge way. When Voltaire and Rousseau started questioning the very fabric of society based on faith and Catholic doctrine, it wasn’t just abstract philosophy; it had real-world implications, even for a piece of painted canvas.

A royal portrait, by its very nature, was a grand statement of traditional authority, often imbued with religious symbolism to underscore the monarch’s divine mandate. But as Enlightenment ideas spread, especially through new institutions like scientific academies, literary salons, and coffeehouses, these symbols began to lose their power. The public, increasingly aware of alternative forms of governance and critical of religious dogma, might look at a king’s portrait not with reverence, but with skepticism or even disdain. The grandeur that once commanded respect could now be seen as extravagant, anachronistic, or even an insult to rational principles.

Consider the French Enlightenment, which found a focus in the monumental project of the Encyclopédie. Compiled by Diderot and d’Alembert, this publication helped spread ideas across Europe that argued for a society based on reason, not faith. In this climate, a royal portrait that presented the monarch as an almost sacred figure, chosen by God, would clash dramatically with the emerging secular worldview. Such an image could be deeply shocking to an enlightened public, revealing a monarch out of touch with the burgeoning intellectual currents and potentially even fueling anti-monarchical sentiments. It was a subtle, yet powerful, shift in how power was visually consumed and critiqued.

3. **Social Contract Theory and the Consent of the Governed**Hold onto your powdered wigs, because this next one is a game-changer: *Social Contract Theory*. This wasn’t just some dusty academic debate; it was the ultimate makeover for how governments were *supposed* to get their power. English philosopher Thomas Hobbes kicked things off with his Leviathan in 1651, but John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau truly spun it into a web of ideas that redefined political legitimacy. Forget divine right; now, the government’s authority was seen as stemming from a “social contract” based on “natural rights” and, crucially, the *consent of the governed*. Talk about a mic drop moment for monarchs!

If a king’s power came from the people’s consent, rather than a heavenly decree, then a royal portrait that depicted him as an absolute, unchallenged ruler would be profoundly shocking. It would be seen as a visual lie, a denial of the very principles that Enlightenment thinkers were championing. Locke explicitly argued that the authority of government was limited and required the consent of the governed. How could a portrait of Louis XIV, famously embodying absolute power, be viewed without intellectual dissonance by someone who had read Locke’s Two Treatises of Government? The artwork would then represent an outdated, even tyrannical, claim to power, rather than a legitimate one.

Rousseau’s take, particularly in “The Social Contract,” even suggested that “civil man” is corrupted, while “natural man” has no want he cannot fulfill himself. He proposed that people join civil society via the social contract to achieve unity while preserving individual freedom. This is embodied in the sovereignty of the general will, the moral and collective legislative body constituted by citizens. This meant that a royal portrait, especially one glorifying a single monarch, could be seen as an affront to collective sovereignty and individual liberty. The visual narrative of the painting would literally contradict the core tenets of modern political thought, making it not just a depiction of a ruler, but a potentially scandalous political statement that flew in the face of what “enlightened” governance should be. Such a portrait, far from being just art, became a lightning rod for political commentary and a stark reminder of the old order’s perceived abuses.

4. **The Quest for Natural Rights**Okay, so we’ve talked about reason and social contracts, but let’s zoom in on something even more fundamental: *natural rights*. This concept was like throwing a wrench into the finely-tuned machine of absolute monarchy. Locke, one of the most influential Enlightenment thinkers, laid it all out: individuals have a right to “Life, Liberty, and Property.” These aren’t just polite suggestions; they are universal and inalienable rights that all men possess, not because a king grants them, but because they are inherent to human existence. Suddenly, the traditional hierarchy where a monarch held all the cards looked incredibly flimsy.

Imagine a grand royal portrait, showcasing a king or queen in all their regal splendor, surrounded by symbols of their inherited power and vast dominion. Now, superimpose the Enlightenment idea that every single person, from the lowliest peasant to the highest noble, is born with equal, inalienable rights. The visual message of profound inequality inherent in such a portrait could be deeply shocking to a public increasingly educated in these radical new principles. The stark contrast between the absolute power conveyed in the painting and the emerging understanding of universal individual rights would be jarring, to say the least.

Locke even argued against indentured servitude on the basis that enslaving oneself goes against the law of nature because a person cannot surrender their own rights: freedom is absolute, and no one can take it away. If freedom is absolute and inherent, how could a portrait that visually reinforces a system of inherited privilege and subservience *not* be shocking? Such an image would serve as a powerful visual reminder of a world that Enlightenment thinkers were actively trying to dismantle. It would highlight the perceived injustices of the “Old Regime” and could easily be interpreted as a defiant, almost arrogant, assertion of power that denied the very humanity and inherent rights of the public.

Read more about: Unlock Your Power: 11 Essential Legal Rights Every American Tenant Must Master for a Stress-Free Rental Life

5. **Emergence of Enlightened Absolutism**And for our fifth mind-bender, let’s explore *Enlightened Absolutism* – talk about an oxymoron that *screams* complexity! This was where some rulers, like Frederick the Great of Prussia, Catherine the Great of Russia, and Joseph II of Austria, actually *welcomed* Enlightenment leaders to their courts. They wanted to apply Enlightenment thought – things like religious and political tolerance – to their governance, but here’s the kicker: they wanted to do it while remaining *absolute monarchs*. It was like trying to have your cake and eat it, too, but with more philosophers and fewer calories.

So, what happens when an “enlightened despot” commissions a royal portrait? The result could be genuinely shocking, but for different reasons than traditional depictions. A portrait might try to blend traditional royal grandeur with symbols of rationality, public service, or even intellectualism. Imagine a king depicted not just with a scepter, but perhaps with books, scientific instruments, or engaged in thoughtful contemplation. While this might have been an attempt to show the monarch as progressive, it could also be deeply confusing or even hypocritical to an enlightened public.

For some, such a portrait might be “shocking” because it didn’t go far enough – it still represented absolute power, even if dressed up in intellectual garb. For others, particularly conservatives or those clinging to traditional religious authority, a portrait that abandoned overt divine symbolism for secular, rational imagery could be equally, if not more, shocking! It signaled a dangerous drift from the sacred foundations of monarchy. Joseph II of Austria, for instance, was “over-enthusiastic” with his reforms, leading to revolts. A portrait of such a figure attempting to embody both absolute power and Enlightenment ideals would undoubtedly provoke a wide spectrum of reactions, creating a visual tension that perfectly encapsulated the era’s grand ideological struggle. These portraits were attempts to navigate a new world, and in doing so, they often inadvertently highlighted the inherent contradictions of their time.

Alright, history lovers, you’ve just seen how Enlightenment philosophy laid the intellectual groundwork, but now let’s crank up the drama! We’re diving into the cultural and political bombshells that didn’t just question royal imagery, but absolutely *transformed* how people saw it. These next six factors weren’t just background noise; they were the seismic shifts that made traditional royal portraits not just old-fashioned, but genuinely *shocking* to the enlightened public. Get ready for some serious upheaval!

6. **The Democratizing Power of Print Culture**So, you know how ideas spread like wildfire on the internet today? Well, back in the Enlightenment, print culture was the original viral sensation! Before this era, information was often controlled, scarce, and, let’s be real, pretty slow. But suddenly, with an expanding print culture of books, journals, and pamphlets, ideas were circulating widely, making enlightenment thinking accessible to an increasingly literate population.

This wasn’t just about reading more novels; it was about spreading revolutionary thoughts! Think about the Encyclopédie, compiled by Diderot and d’Alembert. This monumental project, published in 35 volumes, literally helped spread Enlightenment ideas across Europe and beyond. Suddenly, everyone—or at least, a lot more people—were in on the intellectual buzz, from scientific academies to literary salons and bustling coffeehouses.

What did this mean for royal portraits? Well, with more people reading and discussing radical new concepts like individual liberty and the consent of the governed, a grand painting of an unquestionable monarch wasn’t just admired; it was *scrutinized*. The public was armed with new knowledge, new questions, and a newfound critical eye. A portrait that once projected unquestionable power could now, thanks to print, become a glaring symbol of the very traditions the Enlightenment was actively tearing down, making it truly shocking to a newly informed populace.

Read more about: 10 Proven Strategies to Increase Your Online Following in 2025: Your Blueprint for Digital Dominance

7. **The Influence of Scientific Empiricism on Aesthetic Expectations**Remember how the Scientific Revolution was basically the prequel to the Enlightenment? Well, that emphasis on empirical evidence and the scientific method didn’t just stay in the labs; it totally seeped into how people viewed *everything*, including art! This shift away from superstition and toward rational, observable facts meant that people started looking for realism and truth, even in their royal depictions.

Scientific advancement was super associated with the overthrow of religion and traditional authority. Thinkers had backgrounds in the sciences, and Enlightenment science valued empiricism and rational thought as central to progress. This intellectual climate made people question things that seemed purely symbolic or religiously dogmatic.

So, when a royal portrait came along, steeped in allegorical grandeur and divine symbolism, it might have felt a bit out of sync with the times. An enlightened public, accustomed to the clarity and logic of scientific inquiry, might find a highly stylized, idealized, or overly symbolic depiction of a monarch to be less awe-inspiring and more… well, unconvincing. They wanted something that reflected reality, not just lofty claims.

Interestingly, not everyone was on board with science’s universal benefits. Rousseau himself criticized the sciences for “distancing man from nature and not operating to make people happier.” This critical perspective meant that royal portraits that leaned too heavily on purely “scientific” or rational imagery, perhaps stripping away traditional majesty, might also have shocked some who felt it lost a connection to human essence or beauty, highlighting the era’s complex relationship with progress.

8. **The Seismic Impact of the American and French Revolutions**If the Enlightenment was a slow burn, then the American and French Revolutions were the explosive fireworks that truly lit up the sky! These weren’t just local squabbles; they were global game-changers, deeply influenced by the very Enlightenment ideals we’ve been talking about. And trust us, when heads start rolling (or rather, when colonists declare independence!), royal portraits take on a whole new, often horrifying, meaning.

First, across the Atlantic, the American Revolution (1765–1783) gave flesh and bones to Locke’s ideas. Figures like Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, deeply influenced by European Enlightenment thought, incorporated ideals like natural rights—”Life, Liberty, and Property”—and the consent of the governed into foundational documents like the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. When a government, represented by King George III, didn’t adequately represent the colonists’ interests, the result was a fight for self-governance.

Then came the French Revolution (1789–1799), which saw the systematic dismantling of the *Ancien Régime* – a system of rigid social hierarchy and absolute monarchical power. Think about Alexis de Tocqueville’s observation that the “literary politics” of the Enlightenment promoted equality, fundamentally opposing the monarchical regime. This created a “public opinion” that challenged the monarchy’s legitimacy. The clash between the old “divine right” and the new “consent of the governed” often erupted in violent upheaval, making any symbol of the old order instantly controversial, if not outright condemned.

For a public caught in the fervor of these revolutions, looking at a portrait of a king or queen in all their traditional glory wasn’t just *shocking*; it was an ideological assault. Such images no longer represented stability but tyranny, not divine blessing but the very system being overthrown. They became potent reminders of the past, provoking anger and revolutionary zeal, symbolizing everything the revolutionaries fought against, turning art into a political declaration.

Read more about: Beyond the Leg Warmers: 14 Defining Moments of the 80s That Still Resonate Today

9. **The Burgeoning Ideas of Early Feminist Philosophers**Okay, let’s talk about another revolutionary idea that rocked the Enlightenment world: the burgeoning call for women’s rights! While it might not have caused immediate street riots over paintings, these ideas subtly but profoundly shifted how society, and thus royal imagery, was perceived. When thinkers start arguing for *everyone’s* reason, including women’s, it changes the game for power dynamics, even those displayed on a canvas.

Mary Wollstonecraft, one of England’s earliest feminist philosophers, was a total trailblazer. Her masterpiece, *A Vindication of the Rights of Woman* (1792), argued for a society based on reason, and crucially, that women *as well as men* should be treated as rational beings. This was a direct challenge to deeply entrenched patriarchal norms, which often confined women to specific domestic roles and denied them intellectual equality.

Now, how does this link to royal portraits? Traditionally, royal imagery, especially of queens, often emphasized their roles as mothers, consorts, or symbols of grace, often within a male-dominated power structure. While some queens were powerful, their portrayal rarely challenged the underlying patriarchal assumptions of monarchy. Wollstonecraft’s arguments introduced the idea that a woman’s worth and capacity for leadership should be based on her intellect and reason, not just her lineage or beauty.

Therefore, a royal portrait that presented a queen solely as a decorative figure, or that underscored her position through traditional, restrictive feminine ideals, could be seen as *shocking* to an enlightened individual who believed in women’s rationality and equal rights. It highlighted the dissonance between the progressive ideals of the era and the conservative, often gender-constricting, visual narratives of the monarchy. These portraits inadvertently showcased the inequality that early feminists were fiercely fighting to overcome.

10. **The Contentious Debates Around Religious Tolerance and Secularism**After a century of intense religious conflict, like the devastating Thirty Years’ War, the Enlightenment brought a much-needed breath of fresh air: a push for religious tolerance and even secularism! This wasn’t just a polite suggestion; it was a huge deal, fundamentally reshaping the relationship between church, state, and, yes, even royal portraits.

Enlightenment thinkers were desperate to reform faith to its “non-confrontational roots” and stop religious controversy from spilling into politics and warfare. John Locke advocated for an “unprejudiced examination” of the Word of God, focusing on a simple belief in Christ the redeemer. Others, like Voltaire, famously argued for religious tolerance, stating, “I say that we should regard all men as our brothers.” This progressive stance even led to the “Radical Enlightenment” promoting the concept of separating church and state, a concept Locke is often credited with.

This intellectual movement also saw the development of new religious ideas, including deism—a belief in God the Creator without reliance on the Bible or miracles—and even discussions about atheism. While true atheists were rare, many thinkers, like Pierre Bayle, argued that atheists could indeed be moral. This created a climate where traditional religious dogma and the political power of organized religion were intensely questioned, making them less central to governance and public life.

So, imagine a royal portrait loaded with overt religious symbolism—a king depicted with a halo, receiving divine inspiration, or surrounded by cherubs! To an enlightened public grappling with deism, secularism, and the separation of church and state, such an image could be deeply *shocking*. It wouldn’t just be an artistic choice; it would be a brazen assertion of an outdated, arguably intolerant, worldview that flew in the face of the era’s calls for reason and individual conscience. It was a visual argument for the very intertwining of church and state that many now sought to dismantle.

11. **The Biting Critiques from Influential Figures like Voltaire and Rousseau**Finally, let’s talk about the OG influencers of the Enlightenment: figures like Voltaire and Rousseau, whose razor-sharp wit and profound philosophical critiques weren’t just whispers in salons; they were intellectual grenades that exploded public perceptions, especially of royalty. These guys didn’t just challenge; they *dismantled* old ways of thinking, making royal portraits ripe for their scathing commentary.

Voltaire, a true rockstar of the French Enlightenment, famously argued for a society based on reason, not faith or Catholic doctrine. He even said that an absolute monarch “must be enlightened and must act as dictated by reason and justice,” essentially advocating for a “philosopher-king.” He was so influential that enlightened despots like Frederick the Great welcomed him to their courts, and Voltaire was eager to accept after being “imprisoned and maltreated by the French government.” His critiques, even when aimed at reform, chipped away at the mystique of inherited power.

Then there’s Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose ideas, especially in “The Social Contract,” were truly radical. He suggested that “civil man” is corrupted, while “natural man” is pure. His concept of the “general will” and collective legislative body directly challenged the idea of a single, absolute monarch. These weren’t just academic musings; they were blueprints for a new political order, making any grand display of individual royal power deeply contentious.

When intellectual heavyweights like Voltaire and Rousseau were actively campaigning for reason, individual freedom, and the consent of the governed, any royal portrait clinging to traditional, unquestioned authority was destined to be seen through a critical, often cynical, lens. Their “biting critiques” created an atmosphere where art was no longer just decorative but a political statement, open to intellectual dissection and often found wanting. These portraits, once symbols of unshakeable power, became stark reminders of the old order’s perceived abuses, making them undeniably shocking to a public steeped in revolutionary thought.

Wow, what a journey through the dazzling, dramatic, and downright daring world of Enlightenment art and ideas! From the quiet rise of reason to the thunderous roars of revolution, it’s clear that royal portraits during this era were never just pretty pictures. They were battlegrounds of ideology, canvases of controversy, and reflections of a world furiously rethinking everything it once held sacred. These paintings, in their audacious displays of power or their subtle attempts at modernity, became fascinating, and often *shocking*, snapshots of an age caught between the old world and the bravely dawning new one. Who knew art could be such a troublemaker?