For eons, humanity has gazed upon the Moon, a silent, luminous sentinel in our night sky. We see its familiar face, track its phases, and perhaps even feel its pull in the tides. Yet, beneath this seemingly serene and constant presence lies a world far more complex, dynamic, and frankly, astounding than most realize. Our natural satellite, a celestial body of profound significance to human history, science, and imagination, harbors secrets that could easily be overlooked in a casual glance.

Prepare to embark on a fascinating journey, much like a meticulous archivist unearthing hidden scrolls, to uncover some of the most captivating facts about our Moon. Forget what you think you know; these insights delve into its very essence, from its violent origin story to the peculiar mechanics governing its dance with Earth, and the fiery internal processes that once shaped its rugged visage. It’s a testament to the incredible forces at play in our Solar System and the endless wonders awaiting discovery.

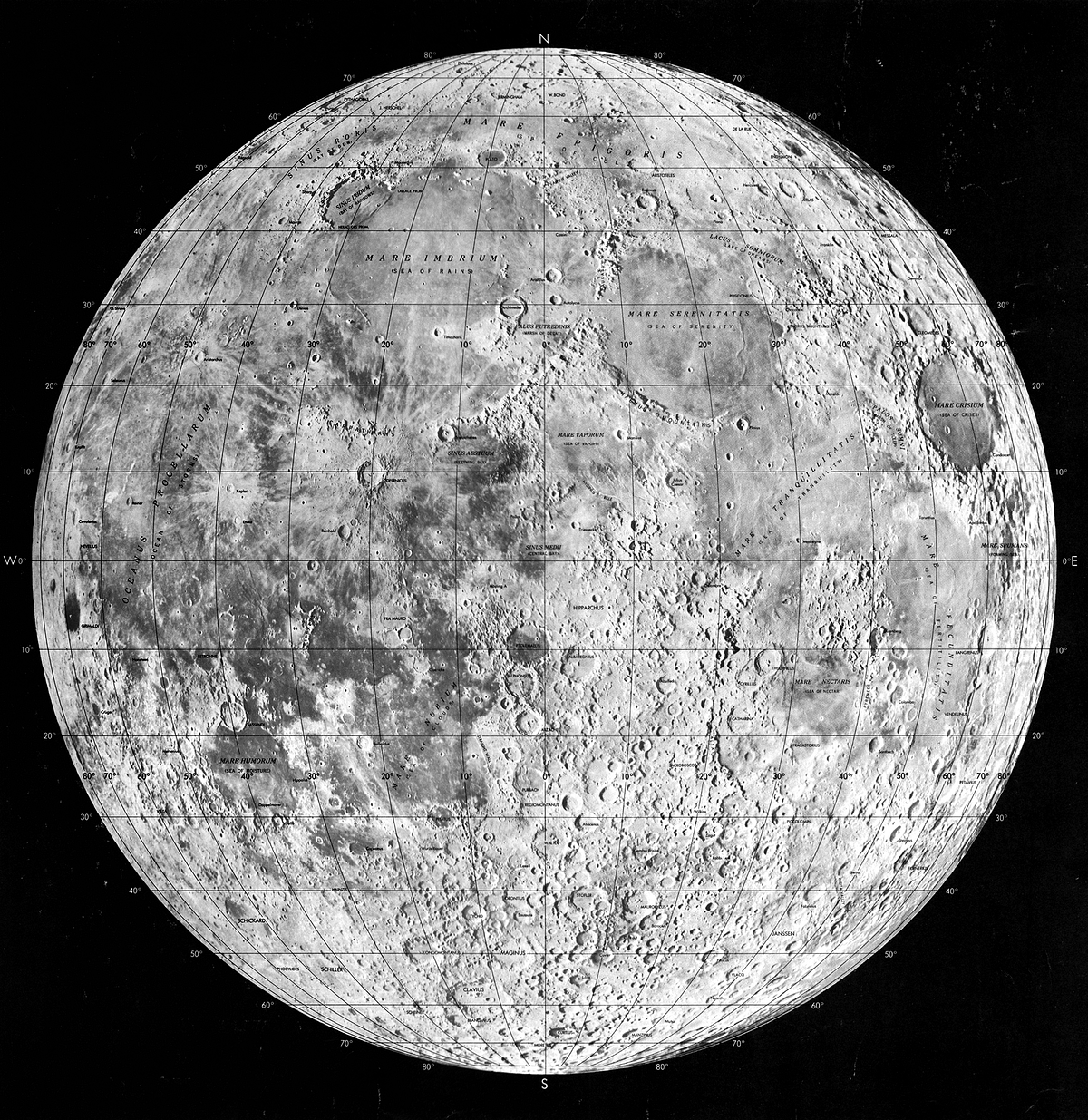

From the ancient observations that mapped its features to the groundbreaking missions that touched its surface, the Moon has consistently pushed the boundaries of our knowledge. In the spirit of uncovering the curious and the compelling, let’s explore fifteen remarkable truths about our closest celestial neighbor, facts that illuminate its extraordinary past and present in ways that are truly out of this world.

1. **The Moon’s Constant Companion: A Tale of Tidal Locking**One of the most widely recognized, yet still deeply fascinating, facts about our Moon is that we always see the same face of it. This isn’t a cosmic coincidence but rather a phenomenon known as tidal locking. For all of recorded human history, and indeed for billions of years before, the Moon has presented an unchanging visage towards Earth, a consistent near side that has inspired countless myths and observations. It’s a remarkable celestial ballet, orchestrated by powerful gravitational forces.

This gravitational synchronization is driven by the mutual pull between the Earth and the Moon. Over eons, the Earth’s gravity has exerted a tidal force on the Moon, causing a bulge in its shape. This bulge is pulled back towards alignment with Earth, and through a process of energy dissipation, the Moon’s rotation gradually slowed down until its rotation period matched its orbital period around Earth. The result is a perfect, albeit permanent, lock: the lunar day is precisely as long as the lunar month.

The implications of tidal locking are profound. It means that while the Moon spins on its axis, it does so at the exact rate it orbits Earth, ensuring that the same hemisphere is perpetually oriented towards us. We only glimpse parts of the far side due to a slight rocking motion called libration, which allows us to see about 59% of the lunar surface over time, but the core principle of its ‘fixed’ face remains a cornerstone of its interaction with our planet.

2. **A Cosmic Cataclysm: The Giant-Impact Origin**The story of the Moon’s birth is anything but serene; it’s a narrative of unimaginable cosmic violence. The prevailing scientific theory, known as the giant-impact hypothesis, posits that the Earth-Moon system formed after a catastrophic collision involving a Mars-sized body, famously named Theia, with the proto-Earth. This wasn’t a gentle nudge but an oblique impact that unleashed colossal energy, dramatically reshaping both celestial bodies.

The immense force of this impact blasted a tremendous amount of material into orbit around the Earth. This ejected debris, a swirling ring of incandescent rock and gas, then accreted over time to form the Moon, just beyond Earth’s Roche limit. Computer simulations of these giant impacts have consistently produced results that align with key characteristics of the Earth-Moon system, such as the mass of the lunar core and its total angular momentum, lending strong support to this dramatic origin story.

Adding another layer of intrigue, Earth and the Moon share nearly identical isotopic compositions of elements like oxygen and tungsten, which is quite unusual compared to other inner Solar System bodies. This isotopic equalization might be explained by the intense mixing of vaporized material that occurred post-impact, although this remains a topic of active debate. Furthermore, recent computer simulations from November 2023 suggest a truly mind-bending possibility: remnants of Theia, the ancient impactor, could still be present deep inside the Earth today.

3. **More Than Just a Satellite: The Moon’s Imposing Scale**While we often refer to it simply as ‘the Moon,’ our natural satellite is a truly significant celestial body in its own right, earning the classification of a ‘planetary-mass object’ or ‘satellite planet.’ Within the vastness of our Solar System, it holds an impressive rank: it is the fifth-largest and fifth-most massive moon overall. Its physical stature is quite remarkable, being smaller than the planet Mercury but considerably larger than the dwarf planet Pluto.

What truly sets our Moon apart, however, is its colossal size in proportion to its parent planet. It holds the distinction of being the largest natural satellite in the Solar System relative to its primary planet. Its diameter measures approximately 3,474 kilometers (2,159 miles), which is roughly one-quarter the width of Earth itself. To put this into perspective, the face of the Moon is comparable to the width of the contiguous United States, or even mainland Australia or Europe.

This impressive scale isn’t limited to its diameter. The Moon’s entire surface area spans about 38 million square kilometers, a vast expanse comparable to that of the entire Americas. With a mass that is 1/81 of Earth’s, it is also the second densest among planetary moons, second only to Jupiter’s Io, and boasts the second-highest surface gravity among all moons in our solar neighborhood. These statistics paint a picture of a celestial body that is far from a mere rock orbiting our world.

4. **Unveiling the Interior: A Differentiated Lunar Structure**Far from being a homogenous sphere of rock, the Moon is a fully differentiated body, meaning it has distinct layers, much like Earth. Its internal structure consists of a geochemically distinct crust, a mantle, and a core, all formed through processes that occurred billions of years ago. This intricate layering provides crucial insights into its formation and evolution, showcasing a complexity that might surprise many.

The Moon’s core structure is particularly intriguing. At its very center lies a solid, iron-rich inner core, estimated to have a radius possibly as small as 240 kilometers (150 miles). Surrounding this solid core is a fluid outer core, primarily composed of liquid iron, with a radius of roughly 300 kilometers (190 miles). These metallic layers are further enveloped by a partially molten boundary layer, extending to about 500 kilometers (310 miles) in radius, indicating areas where material is still in a viscous state.

Beyond the core, the Moon features a hardened mantle and a crust. The crust, on average, is about 50 kilometers (31 miles) thick, though its thickness varies significantly. Lunar rock samples retrieved from flood lavas that erupted onto the surface from partial melting in the mantle confirm that the mafic mantle composition is notably more iron-rich than that of Earth. This layered structure is a testament to the immense heat and geological processes that were active in the Moon’s early history.

5. **A Fiery Cradle: The Ancient Lunar Magma Ocean**Immediately following its violent formation approximately 4.5 billion years ago, the newly coalesced Moon was an incredibly hot place, so hot that it is believed to have possessed its own global magma ocean. This wasn’t just a shallow pool; its depth is estimated to have ranged from about 500 kilometers (300 miles) to a staggering 1,737 kilometers (1,079 miles), potentially encompassing much of the Moon’s interior at the time.

The crystallization of this deep magma ocean was a critical process in shaping the Moon’s internal structure as we understand it today. As the molten rock began to cool and solidify, denser minerals such as olivine, clinopyroxene, and orthopyroxene would have precipitated out and sunk, forming the Moon’s mafic mantle. This gravitational sorting laid the foundation for the distinct layers that characterize its interior.

Once about three-quarters of this vast magma ocean had crystallized, lower-density plagioclase minerals began to form. These lighter minerals, unable to sink through the denser, already solidified mantle, floated upwards, accumulating to form the Moon’s crust. The final liquids to crystallize, rich in incompatible and heat-producing elements, would have been sandwiched between this newly formed crust and the mantle, completing the Moon’s initial geological differentiation. Geochemical mapping from orbit supports this perspective, revealing a crust composed mostly of anorthosite, a type of plagioclase-rich rock.

6. **The Near Side’s Thin Skin: Crustal Asymmetry and Mare Distribution**One of the more subtle yet profound facts about the Moon is the distinct asymmetry in its crustal thickness, particularly between the side that always faces Earth and its hidden far side. Topographical measurements have clearly shown that the near side of the Moon possesses a crust that is, on average, thinner than that of the far side. This geological disparity is not just a curious detail; it has significant implications for how we interpret the Moon’s surface features.

This relative thinness of the crust on the near side is hypothesized to be a key factor in explaining the uneven distribution of the Moon’s most prominent volcanic features: the dark plains of basalt known as maria. With a thinner crust, it would have been easier for lava from the Moon’s interior to breach the surface, flowing out and filling ancient impact basins. This facilitated volcanic activity on the near side, leading to the vast, dark ‘seas’ that we can readily observe from Earth.

Conversely, the far side of the Moon is characterized by substantially thicker highlands. While the exact causes of this distribution are not yet fully understood, one possible scenario suggests that large impacts on the near side may have thinned the crust, making it more permeable to lava. Another intriguing hypothesis ties the thicker far side crust to a slow-velocity impact of a second, smaller moon of Earth, which may have occurred tens of millions of years after the Moon’s initial formation, adding material and thickness to that hemisphere.

7. **A Fiery Past: Billions of Years of Volcanic Activity**Though today it appears largely geologically inert, the Moon was a remarkably volcanically active body for billions of years of its history. This intense period of volcanism fundamentally reshaped its surface, most notably by surfacing vast amounts of lava, primarily on the thinner near side, which filled ancient craters and depressions. As this molten rock cooled and solidified, it formed the today prominently visible dark plains of basalt, which early astronomers mistook for seas, hence their name ‘maria.’

The majority of these immense mare basalts erupted during a period known as the Imbrian period, roughly 3.3 to 3.7 billion years ago, profoundly altering the lunar landscape. However, the Moon’s volcanic timeline wasn’t neatly contained; evidence suggests some mare basalts are as young as 1.2 billion years old, while others date back as far as 4.2 billion years, indicating prolonged and episodic activity over an enormous span of time. This shows a long and complex thermal history for our satellite.

As these maria formed, the cooling and contraction of the basaltic lava created distinct geological features, visible even today. Wrinkle ridges, low sinuous elevations, extend for hundreds of kilometers across some mare surfaces, often outlining buried structures beneath. Additionally, arcuate rilles, concentric depressions along the edges of maria, formed as the immense weight of the basaltic lava caused the underlying crust to sink inwards, leading to fracturing and separation. There are also ‘cryptomares,’ older mare deposits now covered by ejecta from subsequent impacts, hinting at even more widespread ancient volcanism than is immediately apparent.

8. **The Moon’s Tenuous Atmosphere: A Whisper in Space**When we think of the Moon, we imagine a barren, airless void. While you couldn’t breathe there, it’s not entirely without an atmosphere; ‘exosphere’ is a more accurate term. This incredibly tenuous envelope of gas has a total mass of less than 10 tonnes, a mere whisper compared to Earth’s thick blanket. Its surface pressure is an astonishing 3 × 10⁻¹⁵ atm, subtly varying with the lunar day. Its sources include outgassing and sputtering from solar wind ions bombarding lunar soil, releasing elements like sodium, potassium, helium-4, neon, and even radioactive argon-40.

Curiously, common elements like oxygen and carbon, present in the regolith, are absent from this exosphere, a puzzle for researchers. However, Chandrayaan-1 detected water vapor, peaking around 60–70 degrees latitude, suggesting sublimation from regolith ice. These gases are fleeting, either returning to the regolith or lost to space by solar radiation pressure or the solar wind’s magnetic field.

Intriguingly, a permanent dust cloud envelops the Moon, generated by comet particles striking the surface. An estimated 5 tonnes of particles hit daily, sending dust soaring up to 100 kilometers for about 10 minutes. Furthermore, Apollo-era magma samples reveal the Moon once had a relatively thick atmosphere, twice as dense as present-day Mars, 3 to 4 billion years ago, before solar winds stripped it away.

9. **Extreme Lunar Surface Conditions: A Harsh Reality**Beyond its wispy exosphere, the Moon’s surface is a realm of formidable extremes. Ionizing radiation from cosmic rays and the Sun bombards the surface, resulting in an average level of 1.369 millisieverts per day. This is 2.6 times higher than the ISS and 200 times more than Earth’s surface, making robust shielding crucial for future explorers. This intense radiation also electrically charges the highly abrasive lunar dust. This fine silicon dioxide glass, resembling snow, levitates when charged, becoming sticky and damaging to equipment and potentially astronaut health.

Adding to the challenge are radical temperature swings. The Moon’s axial tilt is a mere 1.5427°, minimizing seasonal variations. However, local temperatures fluctuate wildly: direct sunlight brings scorching highs of 120 °C, while areas in shadow plummet to a frigid −171 °C. Permanently shadowed regions, especially at the poles, become some of the coldest places in the Solar System, even colder than Pluto. These deep-frozen pockets are potential traps for volatiles like water ice, but also incredibly challenging to explore.

Finally, the Moon’s surface is blanketed by regolith, a layer of comminuted material from billions of years of impacts. Beneath this lunar soil, with a scent resembling spent gunpowder, lies the megaregolith—a layer of highly fractured bedrock many kilometers thick. These harsh conditions underscore the extreme challenges of living and working on our nearest celestial neighbor.

10. **The Moon’s Fading Magnetic Field: An Ancient Shield**Unlike Earth’s strong global magnetic field, the Moon today possesses only a minuscule external magnetic field, less than 0.2 nanoteslas. That’s less than one hundred thousandth the strength of Earth’s. This seemingly simple fact reveals a complex geological past where an active dynamo once operated, a stark contrast to its current state. Instead of a global field, the Moon exhibits crustal magnetization, a fossilized magnetism embedded within its rocks.

This magnetization was likely acquired around 4 billion years ago when a powerful dynamo, comparable to Earth’s present-day field, operated within the lunar core. This ancient magnetic shield would have provided crucial protection against solar radiation for the early Moon. However, this early dynamo wasn’t destined to last; it apparently expired by about one billion years ago, after the lunar core crystallized and cooled.

Yet, the story continues: some largest crustal magnetizations are near the antipodes of giant impact basins, suggesting transient magnetic fields were generated during large impacts. The Moon also interacts dynamically with Earth’s magnetosphere. Approximately 27% of the time, it passes through Earth’s magnetotail, exposed to ‘Earth wind’ rather than direct solar wind. This subtle magnetic relationship highlights its ties to our home planet.

11. **Gravity’s Lumpy Embrace: Lunar Mascons**While the Moon’s average surface gravity is a mere one-sixth of Earth’s, allowing astronauts to ‘bunny hop,’ its gravitational field is far from uniform. The Moon features significant gravitational anomalies known as ‘mascons,’ or ‘mass concentrations.’ These large positive anomalies are associated with some giant impact basins, causing certain areas to exert a stronger pull, initially discovered by tracking spacecraft accelerations.

Their primary cause is partly attributed to dense mare basaltic lava flows filling those ancient basins. These vast sheets of heavy volcanic rock added significant mass to specific crustal areas. However, the mascon story isn’t entirely straightforward; lava flows alone cannot fully explain all observed gravitational signatures, and some mascons exist without links to mare volcanism. This suggests other geological processes or subsurface structures contribute, an area of active research crucial for orbital navigation.

Beyond its immediate surface, the Moon defines a specific region of gravitational influence. Its ‘Hill radius’ extends about 60,000 kilometers, a sphere where its gravity dominates over Earth’s. This encompasses much of the space between Earth and Moon, extending to the Earth-Moon Lagrange points. This entire region, crucial for spacecraft dynamics, is known as cislunar space.

12. **A Shrinking World: The Moon’s Fault Scarps**For a long time, the Moon was largely considered geologically ‘dead.’ However, recent discoveries reveal a more dynamic picture: our celestial neighbor is still undergoing subtle but significant changes. One compelling piece of evidence for this ongoing activity is the presence of lobate thrust fault scarps—cliffs formed as the Moon contracts.

These fascinating features, identified through detailed imaging, suggest the Moon has shrunk by about 90 meters (300 feet) in circumference within the past billion years. Imagine a grape shriveling into a raisin, but on a grand scale. This global contraction is likely due to the cooling of its interior, causing its outer layers to crack and buckle. This phenomenon isn’t unique to the Moon; similar shrinkage features exist on Mercury.

While the Moon lacks Earth’s dramatic tectonic plates, its tectonic processes are slow yet persistent. Cracks and fault lines continue to develop as it loses residual heat, subtly reshaping its ancient surface. Even areas like Mare Frigoris, once assumed inert, show signs of cracking and shifting. These observations highlight the need for continued geological study of our closest cosmic companion, revealing a subtly evolving body.

13. **Subterranean Sanctuaries: The Lunar Caves**Imagine a natural shelter on the Moon, a place where future astronauts could escape brutal radiation, extreme temperatures, and constant micrometeorite bombardment. Such places exist, and their discovery is one of the most exciting recent revelations: confirmed lunar caves. Scientists identified an entry point to a collapsed lava tube near the Sea of Tranquillity, close to the Apollo 11 landing site.

This specific cave, analyzed from 2010 NASA photos, is roughly 45 meters wide and up to 80 meters long. This is more than a geological curiosity; it’s a potential game-changer for human exploration. The interiors of these lava tubes, shielded by rock, maintain a surprisingly stable temperature of around 17 °C. This offers a far more hospitable environment than the wildly fluctuating surface, protecting against space hazards.

While unlocking their full potential presents challenges, like accessibility and risks of avalanches, the implications for future lunar bases are profound. Such natural sanctuaries could drastically reduce shielding requirements for habitats, making long-duration Moon stays far more feasible and safer. The discovery of confirmed lunar caves has ignited immense excitement, transforming our approach to lunar settlement and scientific research.

14. **Echoes of Fire: Recent Lunar Volcanism**While the Moon’s most dramatic volcanic period occurred billions of years ago, evidence suggests its fiery past isn’t entirely extinguished. In a truly surprising revelation, scientists have found tantalizing signs of much more recent volcanic activity. This challenges the long-held view of the Moon as geologically inert, suggesting its interior might be warmer and more active than previously believed in certain regions.

One significant piece of evidence came from a 2006 study of Ina, a tiny depression in Lacus Felicitatis. This feature exhibited jagged, relatively dust-free characteristics, appearing to be only about 2 million years old—a mere blink in geological terms. Such pristine features indicate surprisingly recent lava flows. Further reinforcing this, over 70 ‘irregular mare patches’ have been identified, some estimated to be less than 50 million years old.

This widespread evidence for relatively recent volcanism raises a fascinating possibility: a warmer lunar mantle, at least on the near side due to greater concentrations of heat-producing radioactive elements. Even on the far side, evidence for 2-10 million-year-old basaltic volcanism has been found within Lowell crater. These discoveries dramatically reshape our understanding of the Moon’s thermal evolution.

15. **The Elusive Lunar Water: A Key to Future Exploration**For decades, the Moon was considered a bone-dry world, devoid of water. However, groundbreaking discoveries have completely overturned this assumption. The Moon is not only home to water but potentially vast quantities, largely as ice. This is arguably one of the most significant revelations for the future of lunar exploration and human presence beyond Earth.

While much of the Moon’s surface is arid, Chandrayaan-1 first detected water vapor in the tenuous exosphere, possibly linked to sublimating ice in the regolith. The real game-changer came with confirming water ice deposits in permanently shadowed craters at the lunar poles. These regions, never touched by sunlight, act as natural cold traps, preserving ice accumulated over billions of years from comet impacts and solar wind.

Lunar water ice isn’t just a scientific curiosity; it’s a strategic resource. If extracted and processed, it could provide breathable air, rocket fuel, and potable water for astronauts. This dramatically reduces material needed from Earth, making lunar bases and deep-space missions more sustainable and cost-effective. This newfound understanding directly fuels ambitious plans like NASA’s Artemis program, transforming the Moon’s water from a little-known fact into a cornerstone of humanity’s off-world future.

And so, our extraordinary journey through the Moon’s hidden truths concludes. From its constant, enigmatic face to its violent birth, from a fiery magma ocean to its current subtle geological dance, the Moon reveals itself as far more complex and dynamic than casual glances suggest. It is a world of extreme conditions, faint atmospheres, and surprising, recent discoveries—a testament to the enduring mysteries of our cosmos.

As we continue to gaze upon our closest celestial neighbor, remember that its silent presence holds countless stories. These narratives patiently await the next generation of explorers. The Moon isn’t just a rock in the sky; it’s a library of cosmic history, a potential stepping stone to the stars, and a constant source of wonder. With every new discovery, it reminds us just how much more there is to learn about the universe, starting right next door.