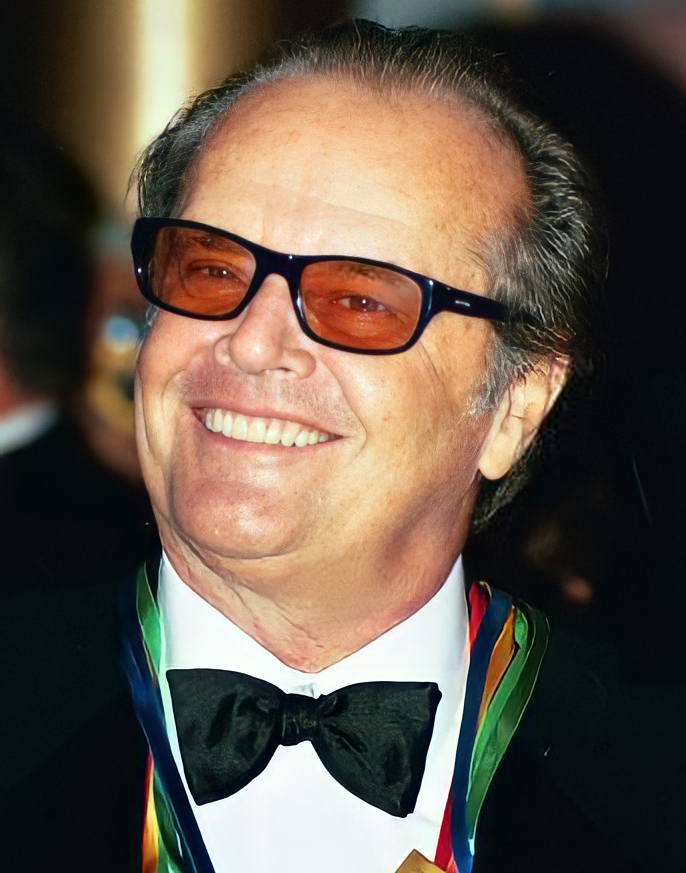

In 1966, a cinematic earthquake rumbled through Hollywood, largely unnoticed by the mainstream, yet it would reverberate through the very foundations of the Western genre for decades to come. As the old guard of Tinseltown began to yield to the audacious spirit of a new generation, two unassuming films emerged from the Utah desert, born of a shoestring budget and boundless creative ambition. These were *The Shooting* and *Ride in the Whirlwind*, directed by the visionary Monte Hellman and starring a young, already exceptionally talented Jack Nicholson.

These weren’t your father’s dusty sagas of square-jawed heroes and clear-cut villains. Instead, Hellman, with Nicholson as his crucial collaborator, was crafting something far more subversive and intellectually potent: the “acid Western.” These films were genre-twisting, existential dramas that would brilliantly deconstruct traditional Western tropes of heroism and masculinity, reframing them for a world ready for “sex, drugs, and rock-and-roll.” Fifty-nine years later, their impact and legacy continue to resonate, proving that sometimes the quietest revolutions leave the deepest imprints.

1. **The Genesis of “Acid Westerns”: Corman, Hellman, and a New Genre** The unlikely birthplace of these groundbreaking Westerns was the fertile, if frugal, imagination of Roger Corman, the undisputed “King of ‘B Movies'”. Known for his ingenious ability to make films “fast and cheap,” Corman’s production model was practically an art form, perfectly suited for ambitious filmmakers with limited resources. It was Corman who spurred Monte Hellman and Jack Nicholson to embark on this dual Western venture, a testament to his knack for identifying raw talent and unconventional ideas.

Hellman and Nicholson had already proven their synergistic capabilities, having previously employed a back-to-back filming method in the Philippines for the thrillers *Flight to Fury* and *Backdoor to Hell*. After pitching an unloved script called *Epitaph* to Corman, the producer, ever pragmatic, inquired if they would consider making a Western instead. When their interest was piqued, he upped the ante, suggesting they film *two* Westerns, an audacious plan that would maximize their resources and creative output.

Thus began the journey into what would later be recognized as the “acid Western” — a nascent genre that would come into full fruition with Alejandro Jodorowsky’s 1970 cult classic *El Topo*. These films, shot on a modest budget in the stark beauty of the Utah desert, were far from the epic scope of John Ford or Anthony Mann. Instead, they embraced an intimate, jagged, anti-narrative fashion, replete with wandering conversations and surreal flights of fancy that dared to mirror the fractured psyches of their characters.

The shared themes, crews, and actors of *The Shooting* and *Ride in the Whirlwind* fostered a cohesive vision, laying the groundwork for a cinematic movement that challenged the very essence of the Western. They weren’t merely stories set in the West; they were philosophical explorations, dissecting the established myths and ethos that had long defined the genre, making them profoundly relevant to a new era of critical, questioning audiences.

2. **Jack Nicholson: Actor, Writer, Producer – His Multifaceted Role in the 1966 Westerns** Even in these formative years, the sheer breadth of Jack Nicholson’s talent was undeniable, evident in his profound involvement in *The Shooting* and *Ride in the Whirlwind*. Not only did he star in both films, but he also penned the screenplay for *Ride in the Whirlwind* and served as a co-producer on *The Shooting*. This multi-faceted engagement speaks volumes about his early dedication and his burgeoning understanding of the entire filmmaking process.

Nicholson’s role as Billy Spear in *The Shooting* marked his 13th film appearance and his fourth collaboration with director Hellman, solidifying a creative partnership that was both productive and, at times, fraught. As a co-producer on *The Shooting*, Nicholson found himself deeply immersed in the challenging realities of independent filmmaking. The film’s meager budget became a constant source of tension, with Hellman famously calling Nicholson’s co-producer decision “the biggest mistake of my life” due to his incessant budget concerns.

These behind-the-scenes skirmishes, however, underscore Nicholson’s commitment to the project, even if it meant clashing with his director over “minuscule budgetary concerns.” His willingness to tackle the financial and logistical headaches alongside his acting and writing duties highlights a hands-on approach that would characterize much of his career. It demonstrates a desire not just to perform, but to shape the narrative and the very existence of these films.

Moreover, his authorship of *Ride in the Whirlwind* further cemented his creative authority, proving he wasn’t just a charismatic face but a keen storyteller with a vision. This early period was a crucial crucible for Nicholson, where he honed not only his acting chops but also his skills as a writer and producer, laying the groundwork for his future iconic status as one of Hollywood’s most versatile and impactful figures.

3. **”The Shooting”: A Bleak, Existential Manhunt Unfolds** *The Shooting* thrusts its audience into a stark, unforgiving landscape, initiating a journey that is as much an internal struggle as it is a physical trek across the desert. The narrative centers on Willett Gashade, a former bounty hunter, and his dimwitted companion, Coley, who are unexpectedly hired by a mysterious, unnamed woman. Their quest takes them through a desolate expanse, where the line between hunter and hunted, good and evil, becomes increasingly blurred.

The unsettling dynamics intensify with the introduction of Billy Spear, played by Jack Nicholson, a black-clad gunslinger who shadows the group, his intentions veiled in menace. This mysterious pursuit forms the backbone of a story that is less about traditional Western action and more about a “Kafkaesque drama,” as critics would later describe it. The film’s climax, famously dubbed “puzzling” by some yet “incredible” and “unexpected” by others, provides no easy answers, leaving a lasting impression of profound ambiguity.

Shot in the vast and unforgiving Utah desert, *The Shooting* eschews grand, sweeping vistas for a more claustrophobic and psychologically intense experience. Its “small casts and limited locations” serve to heighten the sense of isolation and impending doom, stripping away external distractions to focus solely on the raw human drama. This intimate approach, combined with its “jagged, anti-narrative fashion,” allows the film to delve deep into the characters’ “fractured psyche.”

Ultimately, *The Shooting* is a masterclass in thematic deconstruction, focusing on the “manhunt” as a metaphor for existential dread and moral ambiguity. Its bleak climax, where intentions and identities converge in a deadly, enigmatic confrontation, epitomizes the film’s refusal to offer conventional resolution. It challenges viewers to grapple with the “detached fatalism” that defines its world, making it a powerful, enduring piece of cinematic art.

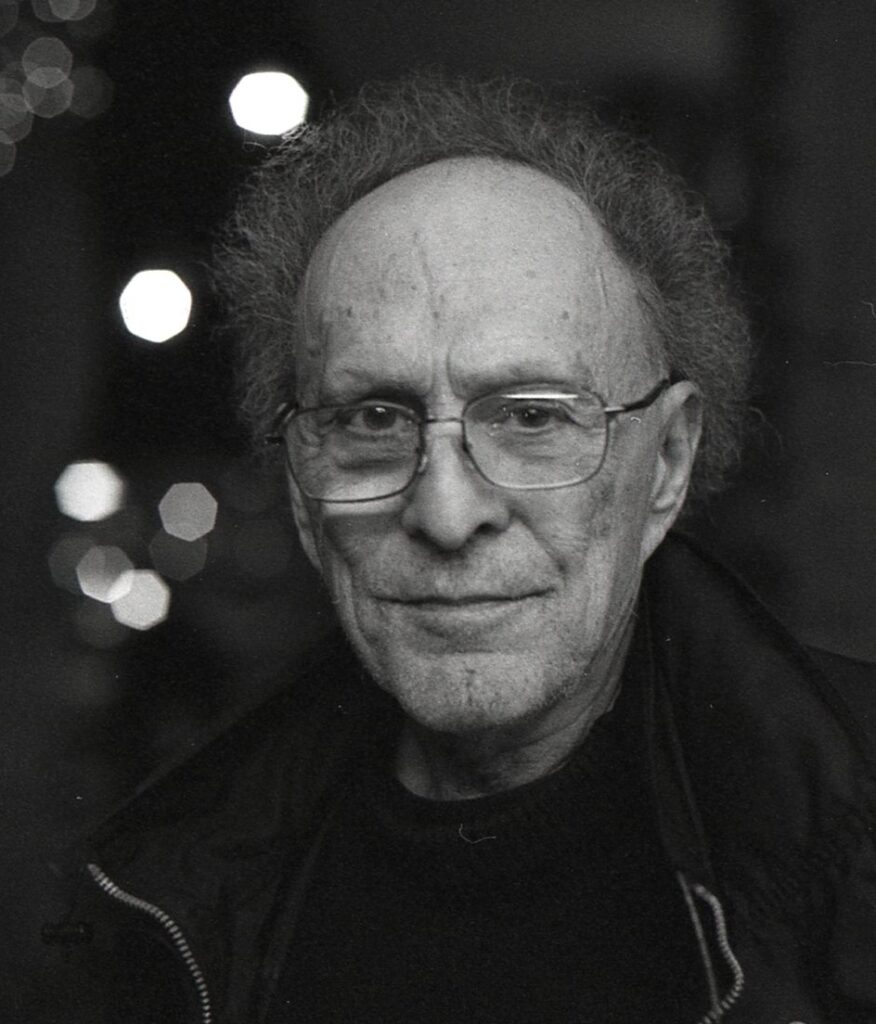

4. **Monte Hellman’s Vision: Anti-Narrative and Fractured Psyches** Monte Hellman, the directorial force behind *The Shooting* and *Ride in the Whirlwind*, was not interested in replicating the grand narratives or heroic archetypes of traditional Westerns. His vision was far more subversive, opting for an “intimate approach” that consciously departed from the “epic scope of John Ford and Anthony Mann.” Hellman’s cinematic language was characterized by a “calculated style, replete with disorientating close-ups and strange moments,” all designed to confirm the “detached fatalism” of his stories.

A defining characteristic of Hellman’s style was his embrace of an “anti-narrative fashion,” where conventional plot progression was often superseded by “wandering conversations and surreal flights of fancy.” This unconventional structure allowed the films to mirror the internal turmoil and “fractured psyche of the characters,” drawing the audience into a more profound, often unsettling, psychological space. He believed that “Exposition, by its very nature, is artificial,” leading him to famously delete the first ten pages of Carole Eastman’s script for *The Shooting*.

Despite Hellman’s artistic conviction, Corman, ever the pragmatist, insisted on inserting some expository material, believing that repeated mentions of Gashade having a brother would prevent audience confusion during the film’s climax. Hellman, though reluctant, eventually conceded. This negotiation between artistic integrity and commercial accessibility underscores the tension inherent in Corman’s B-movie ecosystem, yet Hellman’s core vision largely prevailed, cementing his reputation as a director unafraid to challenge conventions.

Hellman’s meticulous approach extended beyond the screenplay, influencing every aspect of production. He was known for his demanding nature, even clashing with actors like Warren Oates over line delivery, illustrating his unwavering commitment to his artistic vision. The result was a pair of films that are not merely Westerns but deeply philosophical works, laying the groundwork for the “acid Western” and demonstrating Hellman’s unique ability to craft rich, complex narratives from sparse, enigmatic elements.

5. **The Shoestring Budget: Crafting Epic Scope on Limited Resources** The legend of *The Shooting* and *Ride in the Whirlwind* is inextricably linked to their incredibly modest origins. Both films were brought to life on a collective budget of just $75,000 for *The Shooting*, a sum so restrictive it dictated nearly every aspect of their production. Roger Corman’s mandate was simple: make movies fast and cheap, a challenge that Hellman and Nicholson met with remarkable ingenuity, proving that creativity often thrives under severe constraints.

The production crew for *The Shooting* numbered a mere “seven individuals,” a testament to the bare-bones approach. This meant that every member had to wear multiple hats, performing tasks that would typically require an entire department on a larger film. The challenges were immediate and severe, with production on *The Shooting* facing “near-constant rain, which caused severe flooding in the areas where they had planned to shoot,” wasting an estimated $5,000 of the already minuscule budget in the first two days alone.

Beyond the weather, the financial realities forced radical choices. “No lighting equipment was used during the shoot,” requiring cinematographer Gregory Sandor to capture “the entire film in existing light (XL).” For tracking shots, the crew was limited to “about eight feet of dolly tracks,” a constraint that pushed them to find innovative ways to achieve dynamic visuals. The only unionized element of the film, apart from the actors, were the horse wranglers, whose salaries accounted for another $10,000 of the budget.

Despite these formidable limitations, Hellman and Nicholson managed to complete both films within their original budget estimates, shooting *The Shooting* and *Ride in the Whirlwind* in a total of “six weeks of continuous shooting (three weeks per film).” The films, far from hiding their low budgets, openly “wear their low budgets on their sleeves,” transforming what could have been weaknesses into strengths. They demonstrated that a compelling story could be told with “simple elements,” achieving a stripped-down, almost “Samuel Beckett level of inputs,” that ultimately amplified their existential themes.

6. **Warren Oates as Willett Gashade: A Veteran Actor’s Intense Portrayal** When Monte Hellman cast Warren Oates as Willett Gashade in *The Shooting*, he brought aboard a formidable talent already deeply steeped in the Western genre. By 1966, Oates was a “veteran Western character actor,” boasting dozens of film and television series credits in the genre since 1957. Jack Nicholson, Hellman’s co-star and co-producer, immediately recognized the brilliance of the choice, agreeing that Oates would be perfect for the complex, weary bounty hunter role.

However, the creative intensity on set often spilled over into friction, particularly between Oates and Nicholson. The two “repeatedly clashed,” leading to “frequently ending up in screaming matches” during the filming. One notable incident saw Oates refusing to deliver a substantial piece of dialogue as Hellman desired, preferring to “whisper the lines almost unintelligibly.” His defiance led to a walk-off, causing “production had to shut down for half a day” as the director insisted.

Eventually, Hellman allowed Oates to perform the lines his way, provided he also delivered them in the director’s preferred manner. Yet, in the editing room, Hellman ultimately “rejected Oates’s version,” affirming his original vision for the scene. This anecdote, while highlighting the on-set tensions, also speaks to the profound artistic commitment of both actor and director, each pushing for their interpretation of the material.

Despite the clashes, Oates’s portrayal of Gashade is central to the film’s power, imbuing the character with a hardened authenticity and a palpable sense of resignation. His performance anchors the film’s “detached fatalism,” making Willett Gashade a memorable antihero in a genre that was actively seeking to redefine its masculinity. Oates’s raw, intense performance remains a significant component of *The Shooting*’s lasting impact.

7. **Millie Perkins as the Enigmatic Woman: Challenging Western Tropes** Millie Perkins, an actress perhaps best remembered for her poignant portrayal of Anne Frank in *The Diary of Anne Frank*, took on a distinctly different, yet equally compelling, role in *The Shooting*. As Hellman’s next-door neighbor, she was a natural fit for the part of the “enigmatic, unnamed woman” who sets the film’s grim narrative in motion, leading the search party to their ambiguous, and potentially fatal, destination. This was her fifth film, immediately followed by another starring role in Hellman’s companion Western, *Ride in the Whirlwind*.

Perkins’s character is a radical departure from traditional female figures in Westerns. She is neither a damsel in distress nor a romantic interest in the conventional sense. Instead, she is shrouded in mystery, manipulative, and often “rude and insulting” to both Gashade and Coley. Her refusal to disclose her name or her true intentions injects a powerful “Kafkaesque drama” into the narrative, forcing both the characters and the audience to grapple with unresolved questions and unsettling motives.

While Perkins enjoyed the creative environment and became good friends with Warren Oates during the back-to-back productions, she did express a particular frustration with Hellman’s uncompromising insistence on realism. She was “dismayed that Hellman insisted on such realism that he allowed only the most minimal of makeup to be applied to the actors.” This meant she often felt she was “constantly filmed in an unflattering manner,” a sacrifice for the film’s stark aesthetic.

This commitment to raw, unvarnished portrayal, however, served to amplify the woman’s mystique and her role as a catalyst for the film’s existential exploration. Perkins delivers a performance that defies easy categorization, her character an embodiment of the film’s deconstruction of heroism and morality. She is a powerful, unsettling presence, a harbinger of the genre’s evolving understanding of character and motivation, making her a vital element in *The Shooting*’s enduring legacy as a revisionist Western.” , “_words_section1”: “1994

8. **”Ride in the Whirlwind”: An Accidental Pursuit and Moral Ambiguity**Where *The Shooting* plunged its audience into a relentless, enigmatic chase, its companion piece, *Ride in the Whirlwind*, spun a similarly unsettling tale from the opposite perspective: that of the pursued. Released in the same transformative year of 1966, this film, also directed by Monte Hellman, thrusts three innocent cowhands—Wes (Jack Nicholson), Vern (Cameron Mitchell), and Blind Dick (Harry Dean Stanton)—into a nightmare scenario after they unwittingly stumble upon a gang of stagecoach robbers. Before they know it, a posse descends, and the trio finds themselves branded as criminals, forced to flee for their lives.

This narrative pivot, focusing on men caught in a web of mistaken identity and relentless pursuit, allows Hellman to continue his rigorous deconstruction of the Western genre’s moral certainties. The context meticulously outlines the desperate flight of Wes and Vern, who, despite their innocence, resort to taking a rancher, Evan, his wife, Catherine, and their daughter, Abigail (Millie Perkins again, making this a true ensemble cross-pollination), hostage to evade the vigilantes. This scenario creates a powerful ethical dilemma, blurring the lines of culpability and demonstrating the harsh, arbitrary justice of the frontier.

While some might argue that the film offers “little character development, and little character,” as noted in some early critiques, this is precisely where its acid Western sensibilities shine. Hellman isn’t interested in conventional arcs or tidy resolutions; instead, he crafts a visceral, unrelenting experience of survival and paranoia. The desperate journey, culminating in a bleak climax where “two of them die, one is still running,” speaks volumes about a world where innocence is no shield and escape is a fleeting, often fatal, dream. It’s less a story about individuals and more a meditation on the crushing weight of circumstance.

Ultimately, *Ride in the Whirlwind* deepens the thematic explorations begun in *The Shooting*, cementing the pair’s reputation for “examining morality in shades of gray as opposed to black-and-white.” Its narrative of accidental outlawry and the relentless, unforgiving nature of a manhunt from the perspective of the hunted offers a poignant counterpoint to its predecessor. This film, alongside *The Shooting*, proved that the Western landscape could be more than just a backdrop for heroes and villains; it could be a crucible for profound existential inquiry.

9. **Jack Nicholson as Wes: The Reluctant Antihero**Beyond his electrifying, albeit villainous, turn as Billy Spear in *The Shooting*, Jack Nicholson’s fingerprints were even more indelibly pressed upon *Ride in the Whirlwind*. Here, he not only delivered a compelling performance as Wes, one of the three cowhands caught in the posse’s relentless crosshairs, but also penned the screenplay himself. This dual role, combining his burgeoning acting prowess with his undeniable writing talent, underscores the depth of his early commitment to filmmaking and his holistic approach to storytelling.

Nicholson’s authorship of *Ride in the Whirlwind* signifies a crucial moment in his evolution from a charismatic actor to a formidable creative force. The context makes it clear that he “started working on the script for *Ride in the Whirlwind*” while Monte Hellman sought a writer for *The Shooting*. This wasn’t merely a performance; it was a deeply personal narrative shaped by his own vision, a testament to his burgeoning understanding of how to craft a compelling story that defied genre conventions. His ability to conceive and then inhabit such a nuanced character—an ‘innocent’ man thrust into outlaw status—speaks volumes about his multifaceted talent.

As Wes, Nicholson embodies the reluctant antihero, a man whose primary goal is simply survival, devoid of the grand, heroic ambitions often attributed to Western protagonists. His portrayal in *Ride in the Whirlwind* stands in stark contrast to the menacing, black-clad gunslinger Billy Spear. Here, Nicholson navigates a character defined by vulnerability and desperation, showcasing a range that even in his early career, hinted at the versatility that would make him a Hollywood icon. It’s a performance that grounds the film’s bleak existentialism, making Wes’s plight profoundly relatable.

This early period, where Nicholson was juggling acting, writing, and co-producing roles, proved to be a critical crucible. His involvement in *Ride in the Whirlwind* demonstrates a willingness not just to perform within a director’s vision, but to actively shape the narrative itself. It solidified his reputation as a filmmaker who understood the power of unconventional storytelling, laying the groundwork for a career characterized by an eagerness to challenge norms and delve into the complexities of the human condition, even within the confines of a B-movie budget.

10. **Deconstructing Western Tropes: Heroes, Villains, and Shades of Gray**Together, *The Shooting* and *Ride in the Whirlwind* weren’t just two films; they were a double-barreled assault on the very tenets of the traditional Western genre. Hellman and Nicholson, fueled by Roger Corman’s pragmatic creativity, consciously stepped away from the “epic scope of John Ford and Anthony Mann” to forge an “intimate approach” that dissected the established myths of the American West. These films didn’t just tell stories set in the frontier; they were philosophical interrogations, stripping away the romantic veneer to reveal a landscape of moral ambiguity and psychological unease.

The context explicitly states that both films “share many narrative and thematic similarities, from their focus on manhunts to their bleak climaxes. They also both focus on antiheroes, examining morality in shades of gray as opposed to black-and-white.” This was a radical departure from the clear-cut good-versus-evil narratives that had long dominated the genre. In *The Shooting*, the motivations of the enigmatic woman and Billy Spear remain shrouded, and even the protagonist, Gashade, is a former bounty hunter whose moral compass feels weathered by the harsh desert. *Ride in the Whirlwind* flips the script, placing innocent men in the roles of fugitives, forcing audiences to question the very nature of justice and villainy.

This ethical ambiguity and “valorization of outlaws” predated seminal New Hollywood films like *Bonnie and Clyde*, which would, along with *The Graduate*, famously “blew the gates off the Hollywood studio system.” Hellman’s Westerns, made just a year before these game-changers, were already anticipating a shift towards more complex, human-centric narratives. They bravely tackled “sex, drugs, and rock-and-roll generation” themes by challenging the traditional notions of heroism and masculinity, reframing them for an era hungry for authenticity and introspection.

By presenting characters driven by murky motives and caught in inescapable, often fatalistic, circumstances, Hellman and Nicholson crafted narratives that resonated with a generation questioning authority and traditional societal structures. These films dared to suggest that the true West was less about triumphant conquest and more about an arduous, often senseless, struggle for survival, where moral certainties crumbled under the relentless desert sun. Their power lay in their refusal to provide easy answers, leaving a lasting impression that challenged viewers long after the credits rolled.

11. **The Long Road to Recognition: Distribution Woes and Festival Acclaim**In a twist of cinematic irony, two films that would come to redefine a genre initially found themselves adrift in a sea of indifference from their home country. Despite their groundbreaking artistic merit, *The Shooting* and *Ride in the Whirlwind* faced a notoriously difficult path to distribution in the United States. No U.S. distributor expressed any interest in either film after their completion in 1965, leaving Hellman and Nicholson to navigate a frustrating labyrinth of international sales and legal battles.

Initially, Nicholson sold the foreign rights to a French film producer, a promising lead that unfortunately fizzled when the producer went bankrupt, leaving the prints of both films languishing “in bond at the Paris airport for almost two years.” It took “considerable legal maneuvering” for Hellman and Nicholson to reclaim the rights. Yet, a glimmer of hope appeared on the international circuit. In 1967, both films garnered “excellent reviews at the Montreal World Film Festival” and were even shown “out-of-competition at the Cannes Film Festival,” signaling their undeniable artistic impact overseas. In 1968, Hellman managed to secure theatrical showings for both films in Paris, where *The Shooting* impressively became “a sizeable arthouse hit and played for over a year.”

However, American audiences remained largely unaware of these cinematic gems. The U.S. rights were eventually sold to the Walter Reade Organization, a New York-based theatre chain. But even they “decided to pass on a theatrical release,” opting instead to sell “both films directly to television.” This relegated Hellman’s visionary works to the small screen, far from the arthouse recognition they deserved and received abroad. It wasn’t until Jack Nicholson’s star power exploded with his roles in *Easy Rider* and *Five Easy Pieces* (the latter scripted by Carole Eastman, who also wrote *The Shooting*) that these hidden treasures finally began to receive the attention they merited from U.S. audiences.

The journey to appreciation was a long and arduous one, yet ultimately rewarding. The newfound fame of their lead actor prompted Jack H. Harris Enterprises Inc. to obtain theatrical rights in 1971 “on the strength of Jack Nicholson’s new-found fame.” Decades later, the films’ critical standing was further cemented by “pristine restorations by The Criterion Collection.” This slow but steady ascent from obscurity to cult classic status is a testament to their enduring quality, proving that sometimes, truly innovative art just needs a little extra time and a shift in cultural tides to find its audience. As the saying goes, “Better late than never.”

12. **Legacy of the “Acid Western”: Influencing a New Generation**While the term “acid Western” might conjure images of hallucinogenic landscapes and surreal encounters, *The Shooting* and *Ride in the Whirlwind* laid its foundational groundwork with a quiet, yet utterly transformative, power. Jonathan Rosenbaum, a renowned film critic, referred to *The Shooting* as the “first acid Western,” recognizing its pioneering spirit in deconstructing the genre’s familiar contours. These films were instrumental in charting a new course for Westerns, moving away from conventional narratives into more existential, fragmented, and psychologically driven territories.

This nascent genre, initiated by Hellman and Nicholson, found its full “fruition with Alejandro Jodorowsky’s 1970 cult classic *El Topo*,” a film whose overt surrealism and spiritual quest epitomized the ‘acid’ in its designation. The influence of Hellman’s minimalist, anti-narrative approach can also be distinctly traced to later works, with Rosenbaum specifically citing *The Shooting* “as an inspiration for Jim Jarmusch’s *Dead Man*.” Both films share a stark, enigmatic quality, a journey through a desolate landscape that transcends mere plot to delve into profound philosophical questions.

Beyond the ‘acid Western’ label, Hellman and Nicholson’s 1966 double feature played a critical role in paving the way for the broader movement of “revisionist Westerns.” These were films that critically re-examined the myths and legends that had long defined the genre, offering complex, often unflinching, portrayals of the American West. The ethical ambiguity and challenging of traditional archetypes in *The Shooting* and *Ride in the Whirlwind* clearly anticipated the likes of Sam Peckinpah’s *The Wild Bunch*, Arthur Penn’s *Little Big Man*, and Robert Altman’s *Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull’s History Lesson*.

These films were more than just entertainment; they were cinematic provocations, demonstrating that the Western could be a vehicle for profound social and philosophical commentary. They contributed to a seismic shift in Hollywood, helping to usher in an era where filmmakers were eager to tell “more personal, complex stories” that resonated with a questioning, post-sixties audience. The legacy of Hellman’s two desert-baked gems lies in their daring to reinvent a classic genre, proving that sometimes, the most revolutionary cinema springs from the most unconventional of sources.

13. **The Enduring Power of Simplicity: Samuel Beckett and Beyond**Far from being a liability, the notoriously meager budget of just $75,000 for *The Shooting* (and its companion piece filmed immediately afterward) became foundational to their artistic triumph. Roger Corman’s mandate to make films “fast and cheap” forced Monte Hellman and Jack Nicholson into a creative crucible, where limitations bred ingenuity and stripped-down aesthetics became a powerful artistic choice. These films, as the context aptly observes, “wear their low budgets on their sleeves,” transforming what could have been weaknesses into strengths that magnified their profound existential themes.

In a world where cinematic grandeur often equated to lavish expenditures, Hellman and Nicholson dared to prove that a compelling story could be told with “simple elements.” The minuscule production crew, the reliance on “existing light (XL)” for cinematography, and the bare-bones locations of the Utah desert weren’t just cost-saving measures; they were deliberate artistic decisions that heightened the films’ sense of raw, unvarnished realism. This minimalist approach was so effective that, as critic Jonathan Rosenbaum noted, it brought the films to a “Samuel Beckett level of inputs,” underscoring their stark, almost allegorical, exploration of human existence.

This commitment to simplicity is precisely what allowed *The Shooting* and *Ride in the Whirlwind* to transcend their B-movie origins and achieve significant critical acclaim. Critics like David Pirie recognized their profound depth, calling *The Shooting* “probably the first Western which really deserves to be called existential” and a “Kafkaesque drama.” Phil Hardy hailed it as “a marvelous film,” while James Monaco described it as “highly effective, playing with various levels of character and ideas.” The fact that these low-budget, seemingly uncommercial films resonated so deeply with critics and played successfully in Paris arthouses for over a year speaks to their potent, enduring power.

Ultimately, the enduring legacy of these two Monte Hellman Westerns lies in their audacious demonstration that artistic profundity doesn’t require extravagant production values. Instead, it demands a bold vision, intellectual rigor, and an unwavering commitment to storytelling that challenges conventions. By embracing their limitations and transforming them into stylistic virtues, Hellman and Nicholson crafted timeless works that continue to inspire and provoke, proving that sometimes the quietest revolutions, wrought with the simplest tools, leave the deepest and most indelible marks on cinematic history.

Fifty-nine years on, these two unassuming Westerns, born of a shoestring budget and boundless creative ambition in the desolate Utah desert, stand as towering achievements. *The Shooting* and *Ride in the Whirlwind* are more than just films; they are cinematic manifestos, brilliantly deconstructing the very essence of the Western while forging a new path for intelligent, introspective storytelling. They introduced the world to the “acid Western” and paved the way for a generation of revisionist filmmakers, proving that the most profound revolutions often begin not with a bang, but with a quiet, persistent whisper carried on the desert wind.