No movie is set in stone from the second cameras stop rolling, and truer words have rarely been spoken. The magic of filmmaking isn’t just in the shooting; it’s a dynamic, often tumultuous process that continues long after the director yells “cut.” Post-production is a critical phase where a vision truly takes shape, allowing filmmakers to “hone, refine, and fine-tune their vision before settling on their final cut.” But sometimes, the decisions are taken out of their hands, with studios dictating significant changes.

In the realm of cinema, where every frame and line of dialogue is meticulously crafted, it’s astonishing to consider how a single excised moment can ripple through an entire narrative, altering our perception of beloved characters, pivotal plot points, and even the fundamental tone of a film. These aren’t just minor trims; these are sequences that held the potential to transform a movie into something entirely different, sending audiences home with a radically shifted perspective or laying groundwork for sequels that never came to be.

Today, we’re diving deep into the fascinating, often frustrating, world of deleted scenes – those tantalizing glimpses into alternate cinematic realities. With the advent of DVD and Blu-ray, film fans have gained unprecedented access to these “what if” scenarios, allowing us to explore the roads not taken. Join us as we explore 14 infamous deleted movie scenes that, for better or worse, could have changed everything you thought you knew about some of the silver screen’s most iconic productions and sprawling franchises.

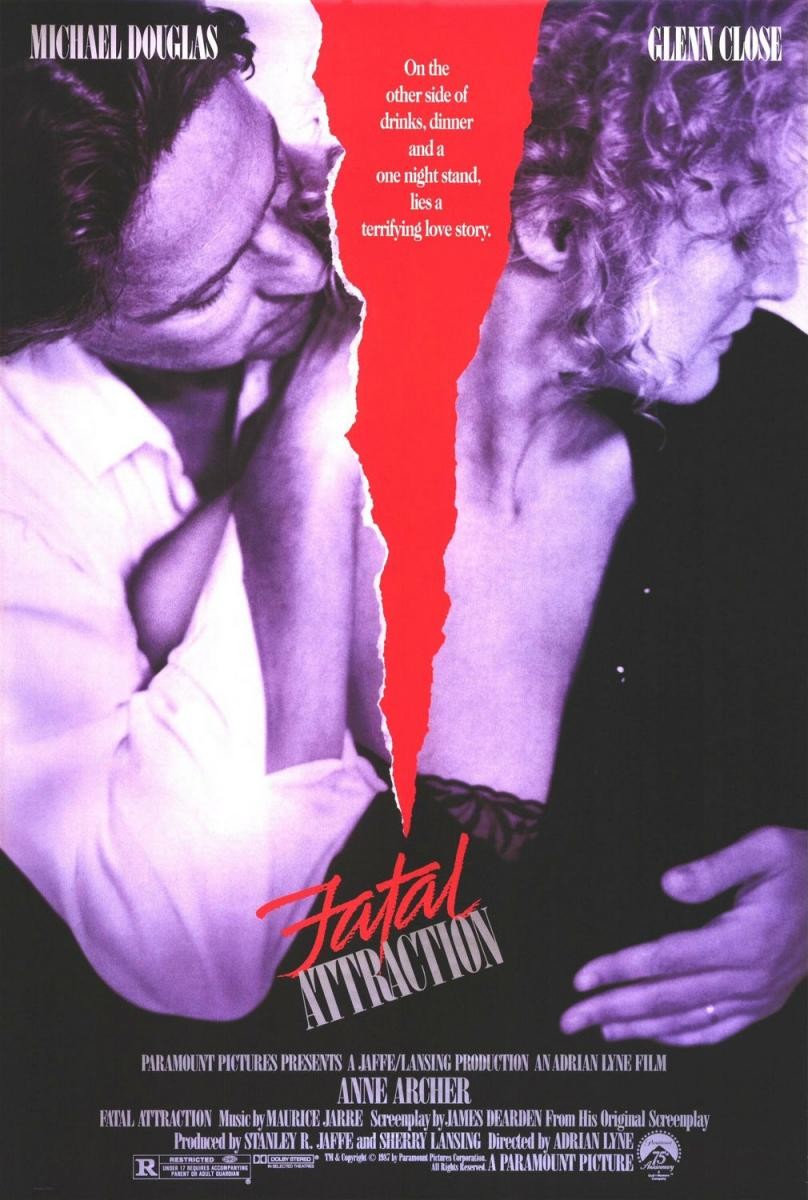

1. **Fatal Attraction (Adrian Lyne, 1987)**:”Fatal Attraction” undeniably “Kickstarting the erotic thriller boom of the late 1980s and early 1990s,” becoming a cultural touchstone with Glenn Close’s unforgettable performance as Alex Forrest. The film’s theatrical ending, as viewers widely remember, culminates in a violent confrontation where Alex, after a terrifying home invasion, “is gunned down by Anne Archer’s Beth Rogerson Gallagher.” It provides a cathartic, if somewhat conventional, resolution to the escalating madness.

Yet, this wasn’t the original, darker conclusion envisioned by the filmmakers. The context reveals that “the movie would have concluded on a serious downer had test audiences not rejected the initial finale.” This original ending saw a much more disturbing fate for Alex Forrest, one that would have left Michael Douglas’s Dan Gallagher in a far more dire predicament. It was a bleak, unsettling climax that would have solidified the film’s tragic undertones.

“Originally, Alex slashes her own throat with the knife she wields to terrorise the Gallaghers, getting the last laugh by going out on her sword and having Douglas’ Dan face a murder charge.” This self-inflicted demise is a chilling act of ultimate control and revenge, framed to implicate Dan in her death. Such an ending would have underscored Alex’s psychological manipulation and determination, painting her as a tragic figure capable of profound self-destruction to achieve her twisted aims.

Close herself “spent two weeks refusing to shoot it until she was convinced,” highlighting the scene’s emotional intensity and the profound impact it would have had on her character’s legacy. Had this original ending stood, “Fatal Attraction would have been a drastically different film,” far less concerned with audience satisfaction and more committed to a harrowing depiction of obsession’s ultimate cost. It would have left audiences with a lingering sense of unease, questioning justice and moral culpability.

2. **Terminator 2: Judgment Day (James Cameron, 1991)**: James Cameron’s “Terminator 2: Judgment Day” is widely heralded as a seminal sequel, pushing the boundaries of action cinema and special effects. A core component of its emotional resonance is the evolving relationship between Edward Furlong’s John Connor and Arnold Schwarzenegger’s T-800, who transforms from relentless killer to unlikely protector and father figure. The film artfully portrays the cyborg’s capacity for learning and empathy.

However, the theatrical cut omitted a scene that would have provided a crucial, scientific explanation for this transformation, deepening the film’s lore and character dynamics. “Director’s cuts have given filmmakers the opportunity to add extra footage to enhance the overall experience,” and T2 is a prime example where such additions could have been profoundly impactful. This particular deleted moment offers an invaluable piece of information that clarifies the T-800’s evolution.

In this excised sequence, “Arnold Schwarzenegger’s cyborg explains to Edward Furlong’s John Connor that when Terminators are mass-produced, their CPU is set to a default setting that prevents them from learning.” This single line of dialogue provides the technical underpinning for the T-800’s capacity for growth, implying that its learning capabilities were initially suppressed and later unlocked or overcome. It makes its development from a machine to a near-human entity more believable.

The scene also features Linda Hamilton’s Sarah Connor, who “doesn’t care,” a detail that “robbing the movie of some integral character development along the way.” The context argues this scene would have achieved multiple narrative goals: “In one fell swoop, it explains how the Terminator could change its ways, establishes John’s growth into a leader, and intimates that Sarah is willing to trust a machine under the right circumstances.” Its omission, “in the name of time constraints,” arguably sacrifices depth for pacing.

3. **Return of the Jedi (Richard Marquand, 1983)**: “Return of the Jedi,” the conclusion of the original “Star Wars” trilogy, resolved many lingering questions, but one major plot point continued to spark debate among fans. “One of the longest-running questions surrounding the original trilogy is why Obi-Wan Kenobi didn’t bother to tell Luke Skywalker that his father wasn’t only alive but Darth Vader.” This central mystery fuels much of Luke’s emotional journey and confrontation with his destiny.

Fortunately, “Yoda offered an explanation, even if it wasn’t in the original cut.” This deleted scene from “Return of the Jedi” provides much-needed clarity on the Jedi Masters’ controversial decision to withhold such critical information from Luke. It directly addresses the ethical dilemma of manipulating a young hero’s fate and the burden of knowledge.

In this excised exchange, “The little green guy explains that he instructed his own protege to withhold that information so it wouldn’t affect Luke’s destiny and prevent the reputation of the Jedi from being tarred by association.” This reveals a calculated, pragmatic side to Yoda, showing a master willing to make difficult, morally grey choices for the perceived greater good of the galaxy and the Jedi Order. It adds layers to their characterization beyond simple wisdom.

“If that had been laid out in the open,” the context suggests, “then it would have shined even more light and added extra depth to the spacefaring father/son duo at the heart of the original trilogy.” This scene not only explains the plot hole but also subtly complicates our understanding of Obi-Wan and Yoda, presenting them as fallible strategists rather than infallible sages. It would have deepened the moral complexities of the Jedi Order itself.

4. **Aliens (James Cameron, 1986)**: James Cameron’s “Aliens” stands as a monumental achievement, a sequel that not only matched but arguably surpassed its predecessor in sheer visceral impact and thematic depth. A significant part of its enduring power lies in the evolving character of Ellen Ripley, masterfully portrayed by Sigourney Weaver, whose transformation into a fierce maternal protector for the young Newt forms the film’s emotional bedrock. This unexpected bond between a hardened survivor and an orphaned child elevates the sci-fi action into a deeply human drama.

However, the theatrical cut omitted a crucial piece of Ripley’s backstory that would have added even greater pathos and clarity to her sudden, powerful maternal instincts. This excised scene, later reinstated in the director’s cut, offered an invaluable insight into Ripley’s emotional state and explained the profound connection she swiftly forms with Newt. It wasn’t just about saving a child; it was about reclaiming a lost piece of her own life.

In a devastating scene that takes place before Ripley blasts off for LV-426, she meets with Paul Reiser’s Carter Burke. Here, she makes the harrowing discovery that while she was in hypersleep for 57 years after the events of the first ‘Alien’ film, her own daughter, whom she had promised to return to by her 11th birthday, had grown old and died. “Awaking 57 years after she first set off with the Nostromo promising to return in time for her 11th birthday, Ripley is shocked to discover that her daughter died while Ripley was in hypersleep.”

This emotionally charged revelation reshapes our understanding of Ripley entirely. It paints her in a softer, more tragic light, clarifying why she so readily adopts Newt as a surrogate child. Without this scene, Ripley’s emergence as a mother figure takes on a slightly different tone, and the profound, almost desperate motivation behind her apparent suicide mission to rescue Newt from the alien hive is less prominent. Its inclusion undeniably enhances “her Academy Award-nominated work,” injecting an even deeper layer of emotional resonance into her character and the film’s central themes of motherhood and sacrifice.

5. **The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980)**: Stanley Kubrick’s “The Shining” is a masterclass in psychological horror, a film that thrives on its unsettling atmosphere and the lingering questions it poses about madness, isolation, and the malevolent forces within the Overlook Hotel. Its chilling ambiguity is a cornerstone of its lasting legacy, allowing viewers to endlessly debate the nature of Jack Torrance’s descent and the true extent of the hotel’s supernatural influence. The film consciously avoids neat resolutions, preferring to leave audiences haunted by what remains unsaid.

However, even a visionary like Kubrick can have second thoughts, as evidenced by a climactic scene that was hastily recalled and cut after the film had already begun screening nationwide. This deleted epilogue would have drastically altered the enigmatic conclusion, providing a level of expository closure that Kubrick ultimately deemed detrimental to the film’s powerful sense of dread and mystery. It offered answers where ambiguity was ultimately more terrifying.

“The Shining had already been playing in cinemas for a week before Stanley Kubrick changed his mind, hastily ordered for all the prints to be recalled, and cut a climactic scene that drastically altered every preceding moment of the movie.” This excised scene “shows Wendy recovering in hospital following her ordeal when Overlook Hotel manager Mr Ullman turns up, explains that Jack’s body was never found, and hands young Danny the very same tennis ball his father had been tossing around during his descent into madness.”

This scene, while seemingly offering a touch of closure, would have introduced a whole new layer of questions that might have undermined the film’s core appeal. The fact that Jack’s body was never found, combined with the reappearance of Danny’s ominous tennis ball, would have firmly cemented the supernatural elements of the Overlook Hotel, rather than letting the psychological interpretations fester. As the context notes, “The classic psychological horror thrives on its unanswered questions, and tying everything up in a neat little expository bow was the wrong call.” Kubrick’s realization, even belatedly, was a testament to his artistic integrity and understanding of horror’s power. Some things are indeed better left unsaid, especially when they contribute to a truly unforgettable chill.

6. **Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines (Jonathan Mostow, 2003)**: While “Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines” may not have ascended to the iconic heights of its legendary predecessors, it carved out its own space as an enjoyable addition to the franchise. Bolstered by engaging performances from Nick Stahl and Claire Danes, who brought a much-needed dramatic weight to the film’s high-octane B-movie sensibility, the film also saw Arnold Schwarzenegger return, injecting a dose of humor into his time-traveling robot assassin. Yet, despite its entertainment value, the film left certain long-standing franchise mysteries deliberately unanswered.

One of the most persistent and often-debated questions among fans across the “Terminator” saga has been the perplexing consistency in the appearance of the T-1000 models. Specifically, why do they all bear the unmistakable likeness of Arnold Schwarzenegger? It’s a fun, albeit unexplained, quirk of the cinematic universe that has fueled countless fan theories and discussions for decades. It’s the kind of lore detail that fans love to dissect and speculate about, adding a layer of meta-narrative to the otherwise serious sci-fi action.

However, “Terminator 3” very nearly provided a definitive, if entirely unexpected, answer to this enduring mystery. A deleted scene from the film, while comedic in tone, would have fundamentally altered this piece of franchise lore. The scene, set within the sterile confines of Skynet headquarters, depicts executives watching a video. This video “explains how the robots are being modeled on a soldier called Sergeant Candy.”

What follows is a delightfully absurd reveal: a grinning Schwarzenegger, portraying Sergeant Candy, describes in a comically “badly dubbed Texan accent” how thrilled he is to have been chosen for the modeling. A watching executive expresses concern over Candy’s distinctive twang, only to be reassured by a co-worker, speaking in a thick German accent, that they “can fix it.” While the gag lands perfectly, director Jonathan Mostow ultimately opted to omit the scene, preferring to “let the mystery be.” This decision, while sacrificing a moment of pure fan service, allowed the enduring question of Arnie’s ubiquitous likeness to persist, leaving it open to interpretation and future, perhaps less humorous, explanations, thereby maintaining a certain mystique around the franchise’s most recognizable icon.

The journey through these deleted scenes is more than just a peek behind the curtain; it’s a powerful reminder of the delicate, often agonizing choices made during the filmmaking process. Each excised moment, whether due to pacing, budget, audience reaction, or a director’s changing vision, represents a road not taken—an alternate reality for characters and franchises we hold dear. They highlight the incredible influence of editing, demonstrating how a few seconds of footage can shift tone, rewrite destinies, and forever alter our perception of cinematic history. These tantalizing glimpses into what might have been ensure that the debates and discussions around our favorite films will continue for generations to come, enriching our appreciation for the art and craft of storytelling.