There’s a peculiar fascination with creatures that once walked, swam, or soared across our planet, but are now forever gone. The very idea of an animal type, perhaps even one resembling our beloved canine companions, vanishing from existence sparks a deep curiosity within us. It’s a journey into the past, a mental exploration of what once was and what lessons we can glean from their silent departure.

While the concept of “dog types” that no longer roam the Earth might immediately bring to mind lost breeds or ancient wolves, the tapestry of extinction is far broader and more intricate. True, documented cases of extinct domestic dog breeds are rare in the historical records provided by scientific context, beyond a few notable canids. However, by looking at a fascinating array of other extinct animal types—from close relatives of modern dogs to iconic megafauna and ancient mammals—we can gain a much richer understanding of the forces that drive species to disappear, and how these forces have shaped the biodiversity of our world, including the ancestors and contemporaries of what we might call “dog types.”

So, prepare to embark on a Mental Floss-style expedition into the annals of natural history. We’re going to uncover some truly remarkable beings that faced the ultimate challenge: survival in a changing world. Each story is a unique blend of biology, environment, and sometimes, the undeniable impact of human activity. Let’s delve into the lives and losses of ten incredible animal types that, for various profound reasons, no longer grace our Earth.

1. **The Japanese Wolf (Canis lupus hodophilax): A Vanished Canine Cousin**The Japanese wolf, known scientifically as *Canis lupus hodophilax*, stands as perhaps the most direct answer to our quest for an extinct “dog type.” A subspecies of the gray wolf, it was once a native inhabitant of the Japanese archipelago. Its story is a poignant example of a species pushed to the brink, with the last universally accepted sighting occurring over a century ago. This makes it a stark reminder that even well-established predators can be incredibly vulnerable.

In the grand scheme of canine evolution, the Japanese wolf was a fascinating branch, adapted to its island environment. Its disappearance highlights the delicate balance of ecosystems and how quickly even formidable animals can succumb to pressures, especially those introduced by human civilization. The concept of local extinction, where a species vanishes from a specific area but exists elsewhere, contrasts sharply with the global extinction suffered by this unique wolf. While some speculate about its continued existence, the scientific consensus largely points to its tragic loss.

Its fate underscores several common themes in extinction: habitat degradation, disease, and direct human predation. As human populations expanded across Japan, natural habitats were converted for farming, reducing the wolf’s territory and prey. Additionally, disease outbreaks, likely introduced through domestic animals, would have further decimated their numbers. The Japanese wolf’s story is a sober lesson in the swift and devastating consequences that can arise when a species is unable to adapt to drastic changes in its environment or withstand intense human-driven pressures.

2. **The Thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus): The Marsupial ‘Wolf’ of Tasmania**Moving slightly beyond the strict definition of a “dog type” but certainly within the realm of “dog-like” creatures that roamed, we encounter the magnificent thylacine, *Thylacinus cynocephalus*. More commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger or Tasmanian wolf, this unique marsupial carnivore was an apex predator native to Tasmania. Despite its striped coat earning it the “tiger” moniker, its overall build, skull structure, and predatory lifestyle bore a striking resemblance to a canid, leading to its “Tasmanian wolf” designation, a perfect illustration of convergent evolution.

Its extinction is one of the most well-documented and heartbreaking of modern times. The last known thylacine, named Benjamin, died in Hobart Zoo in Tasmania in 1936. This relatively recent disappearance offers invaluable, albeit tragic, insight into how human actions can swiftly eradicate a species. The thylacine was hunted relentlessly, primarily by European settlers who viewed it as a threat to livestock, often with government bounties exacerbating the persecution. This relentless “overharvesting” combined with habitat destruction significantly contributed to its demise.

Despite its official extinction, the thylacine remains a poignant example of a “Lazarus species” in the realm of speculation. Its name often appears in discussions of animals thought extinct but with ongoing (though often unverified) sightings. The memory of the thylacine serves as a powerful symbol of the irreversible loss of biodiversity and a stark reminder of the urgent need for conservation efforts to prevent similar fates for other endangered species. It challenges us to consider what we truly lose when a unique branch of the tree of life is severed forever.

3. **Mammoths: The Gentle Giants of the Ice Age**From fearsome predators, we turn our attention to the colossal mammoths, another “notable extinct animal species” that truly characterized ancient landscapes, much like their modern elephant relatives today. These magnificent herbivores, often depicted with their distinctive long, curved tusks, were once widespread across northern continents. While clearly not a “dog type” in any sense, their story is critical to understanding the loss of megafauna that once shared vast territories with early canids and humans, painting a grander picture of life that no longer roams our planet.

From fearsome predators, we turn our attention to the colossal mammoths, another “notable extinct animal species” that truly characterized ancient landscapes, much like their modern elephant relatives today. These magnificent herbivores, often depicted with their distinctive long, curved tusks, were once widespread across northern continents. While clearly not a “dog type” in any sense, their story is critical to understanding the loss of megafauna that once shared vast territories with early canids and humans, painting a grander picture of life that no longer roams our planet.

Mammoths represent a monumental loss from Earth’s biodiversity, captivating our imagination with their sheer size and adaptation to cold climates. Their extinction, predominantly occurring tens of thousands of years ago, is often cited in discussions about the interplay between rapid climate change and the impact of early human populations. The context notes that “human-driven extinction started as humans migrated out of Africa more than 60,000 years ago,” and the swift extinction of megafauna in areas like North and South America around 12,000 years ago is often linked to the “overkill hypothesis”—the idea that newly arrived human hunters, encountering animals unadapted to their predation techniques, caused rapid population declines.

The disappearance of mammoths serves as a stark reminder of the vulnerability of even the largest and most seemingly resilient species when faced with profound environmental shifts and persistent human pressures. Their story is a cornerstone in the scientific understanding of extinction, helping to illustrate how habitat degradation, climate change, and human-induced predation can combine to extinguish an entire “type” of animal from the face of the Earth. The recovery of such massive phylogenetic diversity, as noted in a 2018 report, would require millions of years, underscoring the irreversible nature of their loss.

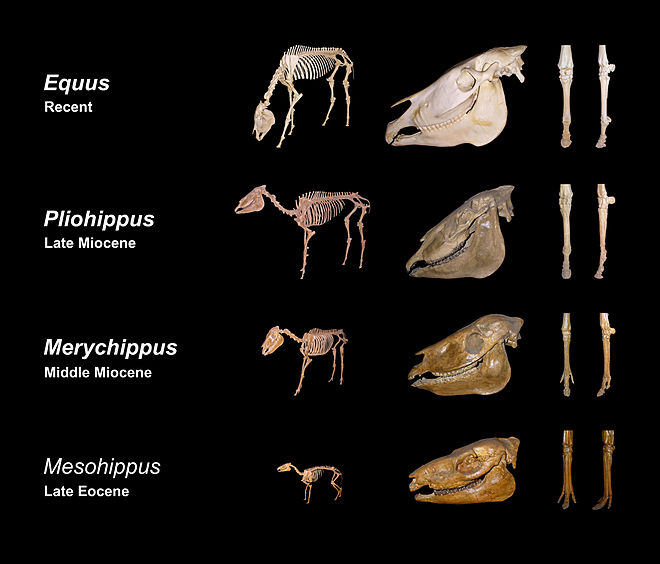

4. **Hyracotherium (Early Horse): The Ancestor That ‘Pseudo-Extincted’**Our journey through extinct animal types takes us to the truly ancient, to a creature that embodies a fascinating concept of disappearance: the *Hyracotherium*. Often referred to as an “early horse,” this small, dog-sized mammal might not resemble its modern equine descendants, but its story is crucial for understanding “pseudoextinction,” or phyletic extinction. It’s a prime example of an animal “type” that no longer roams the Earth in its original form because it evolved into something new.

*Hyracotherium* is sometimes claimed to be pseudoextinct rather than extinct because its lineage continued to transform, leading to the diverse species of *Equus* we see today, including zebras and donkeys. In essence, the original taxon vanished, not by dying out completely, but by being transformed through the process of anagenesis into successor species. This concept is a cornerstone of evolutionary biology, highlighting that species don’t always end in a dead-end, but can evolve into new forms.

However, demonstrating pseudoextinction is a complex scientific endeavor. As the context points out, “as fossil species typically leave no genetic material behind, one cannot say whether *Hyracotherium* evolved into more modern horse species or merely evolved from a common ancestor with modern horses.” Regardless of this scientific challenge, *Hyracotherium* represents an early mammalian “type” whose story underscores the dynamic, ever-changing nature of life on Earth. Its legacy lives on not in its original form, but through the vibrant diversity of horses and their relatives that continue to roam today, a testament to the power of evolution and the diverse ways a species can ‘leave’ the Earth as we knew it.

5. **The Dodo (Raphus cucullatus): A Symbol of Swift, Human-Driven Loss**From the ancient past, we leap to a more recent, and perhaps more famously tragic, tale of extinction: the dodo. This flightless bird, native to the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean, has become an enduring symbol of species loss, its very name synonymous with a vanished existence. Unlike the vast timescales associated with prehistoric extinctions, the dodo’s demise unfolded rapidly, a mere blink in geological time, driven almost entirely by the arrival of humans and the creatures they brought with them.

The dodo was a plump, unsuspecting bird, unaccustomed to predators in its island paradise. Its evolutionary journey had led it to a life of abundance without the need for flight, making it exceptionally vulnerable when new threats emerged. European sailors, who began visiting Mauritius in the late 16th century, found the dodo an easy source of fresh meat. However, it wasn’t just direct hunting that spelled doom for *Raphus cucullatus*; the indirect impacts were far more insidious and devastating.

The true culprits behind the dodo’s swift decline were the invasive species introduced by human visitors. Pigs, rats, and monkeys, escaping from ships, found the dodo’s ground-nesting habits and defenseless chicks an easy feast. These new predators, combined with the clearing of forests for human settlement and agriculture, decimated the dodo population with alarming speed. By the late 17th century, a little over a century after its first recorded sighting, the dodo was gone, an “often-cited example of modern extinction,” as the context aptly notes.

The dodo’s story is a powerful, if grim, lesson in the fragility of island ecosystems and the profound, often unforeseen, consequences of human activity. It highlights how a species, perfectly adapted to its unique environment, can be utterly unprepared for external pressures. Its legacy continues to serve as a cautionary tale, spurring conservation efforts worldwide to prevent other vulnerable island species from following in its wingless footsteps.

6. **The Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius): From Billions to Zero in Decades**Imagine a sky so darkened by birds that it took hours for the flock to pass overhead. Such was the reality of the passenger pigeon, *Ectopistes migratorius*, once the most abundant bird in North America, possibly even the world. Their numbers were truly staggering, estimated to be between 3 to 5 billion individuals at their peak, constituting up to 40 percent of the total bird population of North America. Yet, in less than a century, this once-ubiquitous species was hunted to extinction, a shocking testament to the speed and scale of human-driven loss.

The sheer volume of passenger pigeons meant they were considered an inexhaustible resource. Early European settlers and later commercial hunters engaged in “overharvesting” on an industrial scale. Their enormous flocks made them easy targets, and methods ranged from nets to shotguns, often targeting nesting colonies. The meat was cheap protein, and the birds were even used as fertilizer. This relentless, unsustainable hunting pressure was the primary driver of their catastrophic decline, a brutal illustration of how intense human exploitation can wipe out even seemingly limitless populations.

Beyond hunting, habitat destruction played a significant, albeit secondary, role. The passenger pigeon relied on vast tracts of old-growth forests for nesting and foraging, particularly for mast crops like acorns and chestnuts. As these forests were cleared for agriculture and timber, the pigeons’ habitat fragmented and dwindled. Their social behavior, which involved nesting in enormous, dense colonies, also made them vulnerable; once their numbers dropped below a critical threshold, their ability to reproduce successfully plummeted, leading to an extinction vortex.

The last known passenger pigeon, named Martha, died in the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914, bringing a poignant end to a species that had literally overshadowed the continent. The passenger pigeon’s story is a chilling reminder that immense numbers offer no guarantee against extinction, especially when faced with unchecked human exploitation and habitat loss. It powerfully illustrates how “human-driven extinction started as humans migrated out of Africa more than 60,000 years ago,” and intensified dramatically in recent centuries, underscoring the irreversible nature of such a profound loss.

7. **The Moa and Haast’s Eagle: A Cascade of Coextinction in Aotearoa**Our next entry unveils a tragic duo, two distinct animal types whose fates were inextricably linked: the mighty moa and the formidable Haast’s eagle of New Zealand. Their story is a classic example of “coextinction,” where the disappearance of one species directly precipitates the demise of another. It’s a vivid illustration of the intricate web of life, where severing one thread can unravel an entire tapestry, especially when it involves a keystone species or a predator-prey relationship.

The moa were a group of nine species of flightless birds endemic to New Zealand, ranging in size from turkey-like to towering giants over 3.6 meters (12 feet) tall. They were the dominant herbivores of their ecosystem, living for millions of years in the absence of mammalian predators. This made them uniquely vulnerable when humans—the Māori settlers—arrived in New Zealand around 1300–1500 AD. The moa were an easy and abundant food source, and within a few centuries, all moa species were hunted to extinction, a clear case of the “overkill hypothesis” playing out in real-time.

Enter the Haast’s eagle, *Harpagornis moorei*, the largest eagle known to have existed, with a wingspan of up to 3 meters (9.8 feet). This colossal raptor was New Zealand’s apex aerial predator, uniquely adapted to hunt the large, slow-moving moa. Its immense size and power were perfectly suited for taking down such formidable prey. As the moa populations plummeted due to human hunting, the eagle’s primary food source vanished. With no alternative large prey readily available, the Haast’s eagle inevitably followed its prey into oblivion.

The coextinction of the moa and Haast’s eagle is a profound example of how human-induced changes can cascade through an ecosystem, leading to multiple losses. As the context explains, “Coextinction refers to the loss of a species due to the extinction of another; for example, the extinction of parasitic insects following the loss of their hosts.” Here, the predator lost its prey, showcasing the delicate balance of ecological niches. Their story powerfully reminds us that even seemingly indirect actions can have widespread, devastating effects on biodiversity, creating “chains of extinction” that are tragically irreversible.

8. **Palaeotherium and Anoplotherium: Unearthing the Concept of Extinction with Georges Cuvier**Venturing further back into the Eocene epoch, approximately 56 to 34 million years ago, we encounter two “animal types” that are crucial not just for their own existence, but for how they revolutionized our understanding of extinction itself: *Palaeotherium* and *Anoplotherium*. These ancient mammals, distinct from any living species, became the cornerstone of Georges Cuvier’s groundbreaking work, challenging deeply held beliefs about the completeness and perfection of nature and paving the way for the modern scientific acceptance of species vanishing forever.

Before Cuvier, the prevailing scientific and theological view in Western society, often tied to the “great chain of being,” asserted that species did not truly go extinct. If an animal was no longer seen, it was simply “hiding” in an unexplored corner of the globe. However, Cuvier, a brilliant geologist and anatomist, brought irrefutable fossil evidence to the table. By meticulously comparing the fossilized jaws and skeletons of *Palaeotherium* and *Anoplotherium*—which he named—to those of living animals, he concluded that these were not merely variants but entirely different forms of life that no longer existed.

Cuvier’s work on these and other fossils from the Paris Basin, where he observed patterns of appearance and disappearance across geological strata, led him to propose a radical idea: that Earth had experienced “historic cycles of catastrophic flooding, extinction, and repopulation of the earth with new species.” *Palaeotherium*, described as an “extinct genus that is only recorded from fossil records before the existence of hominids,” and *Anoplotherium*, a contemporary Paleogene mammal, were central to his argument that life forms could indeed be permanently lost from the planet, possibly due to events like the “Grande Coupure extinction event.”

The significance of *Palaeotherium* and *Anoplotherium* lies not just in their own biological history, but in their pivotal role in establishing the “modern conception of extinction.” Cuvier’s rigorous comparative anatomy demonstrated that these were distinct animal types, irrevocably gone. Their study shattered the old paradigms, forcing the scientific community to confront the reality of deep time and the impermanence of species, fundamentally altering our understanding of Earth’s biological past and the natural processes that shape it.

9. **The Non-Avian Dinosaurs: The Ultimate Mass Extinction Event**No discussion of extinct “animal types” would be complete without paying homage to the undisputed champions of ancient Earth: the non-avian dinosaurs. For over 160 million years, these magnificent reptiles dominated terrestrial ecosystems, evolving into an astonishing array of forms, from the towering sauropods to the fearsome *Tyrannosaurus*. Their dramatic disappearance approximately 66 million years ago, known as the Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) extinction event, represents perhaps the most iconic and thoroughly studied “mass extinction” in our planet’s history.

The K-Pg event was a truly cataclysmic affair, wiping out roughly three-quarters of all plant and animal species on Earth, including every non-avian dinosaur. While the precise details are still debated, the overwhelming scientific consensus points to the impact of a massive asteroid or comet near what is now the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico as the primary trigger. This impact would have unleashed a global winter, caused widespread fires, acid rain, and blocked out sunlight, devastating photosynthesis and collapsing food chains across the globe.

While the dinosaurs were not “dog types” in the traditional sense, their story is absolutely essential for understanding the concept of mass extinctions—”relatively rare events; however, isolated extinctions of species and clades are quite common, and are a natural part of the evolutionary process.” The K-Pg event stands as a stark reminder that even dominant and seemingly invincible species can be vulnerable to sudden, profound environmental shifts. It showcases a different scale of extinction from human-driven losses, a natural catastrophe that reshaped the entire trajectory of life on Earth.

The legacy of the non-avian dinosaurs lives on, not only in the fascination they inspire but also in the crucial lessons they teach us about planetary resilience and vulnerability. Their extinction opened up ecological niches, allowing for the rapid diversification and ascendancy of mammals, including our own distant ancestors. Thus, while they no longer roam the Earth in their ancient forms, their demise was a pivotal moment, fundamentally altering the course of evolution and underscoring that extinction, in its grandest scale, is an undeniable, powerful force of nature.

Our journey through these ten remarkable “animal types” that no longer roam the Earth offers a poignant reflection on life’s impermanence and the dynamic forces that shape our planet’s biodiversity. From the tragic tales of the dodo and passenger pigeon, illustrating humanity’s swift, devastating impact, to the intricate coextinctions of the moa and Haast’s eagle, and the ancient revelations of Cuvier’s *Palaeotherium*, each story unveils a unique facet of extinction. The ultimate drama of the non-avian dinosaurs reminds us that life on Earth has always been subject to profound, cataclysmic changes. These vanished creatures are more than just historical footnotes; they are invaluable teachers, urging us to understand the delicate balance of ecosystems and to safeguard the incredible diversity that still graces our world. Their stories serve not as somber endings, but as compelling calls to action, inspiring a deeper appreciation for the life that surrounds us and a renewed commitment to its preservation.