The narrative of Ukraine is inextricably linked with an enduring struggle for self-determination amidst centuries of external influence and geopolitical contestation. Situated at the crossroads of Eastern Europe, its geography has perpetually placed it in the crucible of competing empires, shaping a rich yet often tragic history. Understanding this complex past is imperative for comprehending the profound challenges the nation faces today and the wider implications for global stability.

From its earliest human settlements dating back tens of millennia to its emergence as a pivotal centre of East Slavic culture, Ukraine’s journey is a testament to persistent cultural identity and resilience. The nation’s experience, marked by periods of remarkable power and cultural flourishing, has always been punctuated by fragmentation and external domination. This analysis delves into the foundational chapters of Ukraine’s story, meticulously tracing its evolution from antiquity through the transformative upheavals of the early 20th century.

1. **The Etymology and Sovereignty of “Ukraine”**

The very name of Ukraine carries a deep historical resonance, frequently interpreted from the Old Slavic term for ‘borderland,’ or ‘krajina.’ This interpretation, prevalent in the English-speaking world for much of the 20th century, led to the common usage of “the Ukraine.” Such phrasing, mirroring “the Netherlands,” suggested a geographical region rather than an independent sovereign entity, reflecting a perception rooted in its contested existence.

However, since Ukraine’s declaration of independence in 1991, this linguistic nuance has undergone a significant political transformation. The usage of “the Ukraine” has become politicised and is now considerably rarer, with contemporary style guides advising against it. The official Ukrainian position states that “the Ukraine” is both grammatically and politically incorrect, signifying a rejection of any implication that diminishes its hard-won sovereignty.

2. **Ancient Roots: Early Human Inhabitation and Proto-Indo-European Origins**

The land constituting modern Ukraine boasts an exceptionally deep history of human presence. Evidence of hominin habitation dates back an astonishing 1.4 million years, demonstrated by stone tools discovered at Korolevo in western Ukraine. Modern human settlement is securely dated to 32,000 BC, marked by the Gravettian culture in the Crimean Mountains. This rich archaeological record highlights Ukraine’s ancient role as a cradle of human civilisation in Europe.

Further testament to Ukraine’s ancient significance is the flourishing of the Neolithic Cucuteni–Trypillia culture by 4,500 BC, spanning wide areas including the Dnieper-Dniester region. Ukraine is also considered a probable location for the first domestication of the horse, an event that profoundly reshaped human societies. Moreover, the Kurgan hypothesis posits the Volga-Dnieper region as the linguistic homeland of the Proto-Indo-Europeans, whose migrations spread their ancestry and languages across vast swathes of Europe.

3. **The Golden Age of Kievan Rus’: A European Powerhouse**

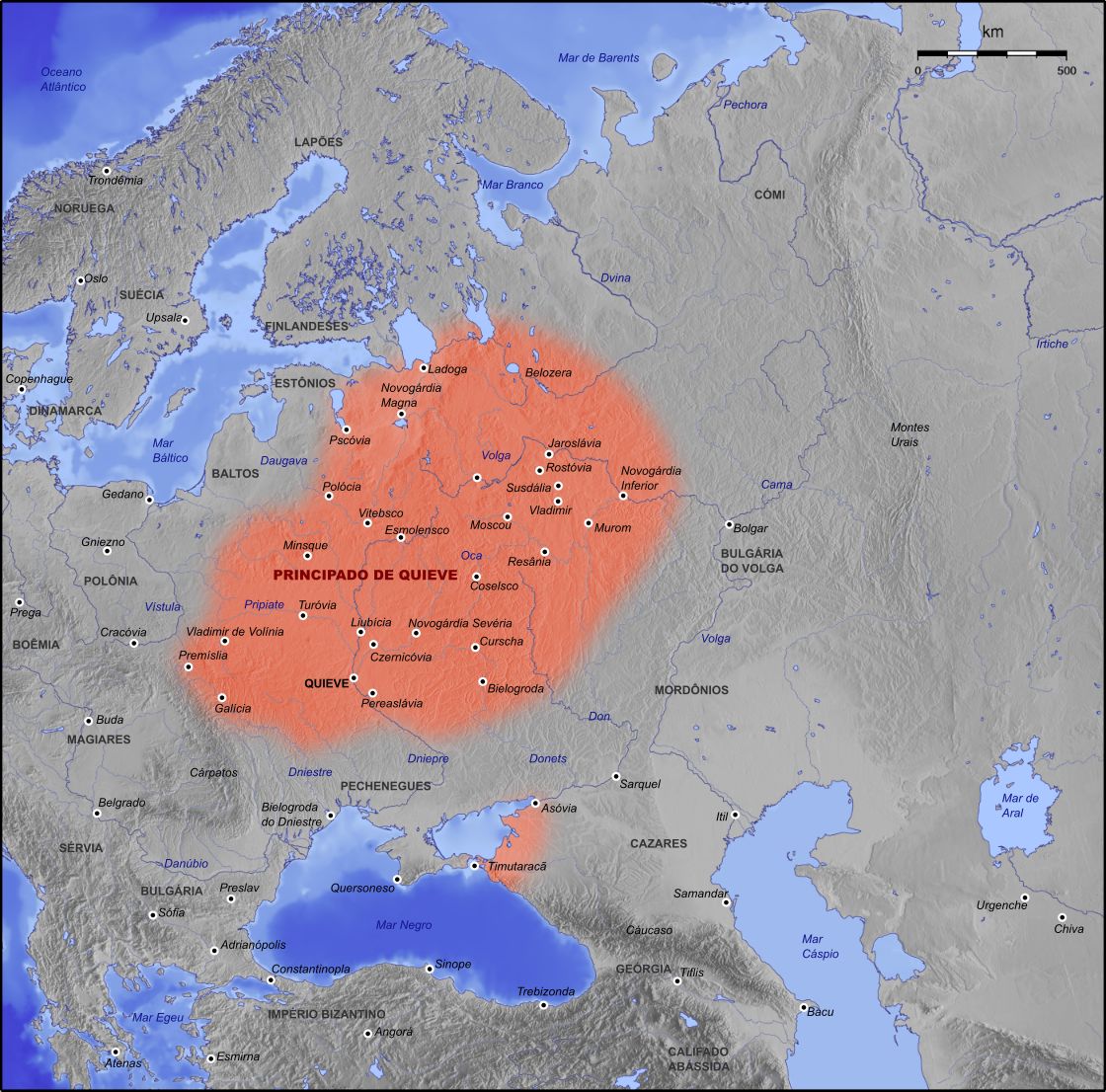

The emergence of Kievan Rus’ in the 9th century marked a transformative period, encompassing much of present-day Ukraine, Belarus, and western European Russia. While accounts like the Primary Chronicle suggest a Varangian (Norse) origin, other historians argue for independent state formation among East Slavic tribes, with the Varangian elite later assimilating. Kievan Rus’ achieved its zenith of cultural development and military power during the 10th and 11th centuries, an era known as its Golden Age.

This era commenced notably with the reign of Vladimir the Great (980–1015), who introduced Christianity, a pivotal event. His son, Yaroslav the Wise (1019–1054), further consolidated this power, establishing a realm arguably the largest and most influential in Europe. Despite its strength, Kievan Rus’ eventually fragmented into separate principalities following Mstislav’s death in 1132. The Mongol invasions in the mid-13th century delivered a devastating blow, destroying Kyiv in 1240 and ending Kievan Rus’ as a unified power, paving the way for subsequent foreign dominations.

4. **Centuries of Contestation: Ukraine Under Foreign Domination**

Following the demise of Kievan Rus’, the lands of Ukraine entered a prolonged period of foreign domination, becoming a battleground for various external powers for six centuries. In the west, the principalities of Halych and Volhynia merged to form the Principality of Galicia–Volhynia, briefly reuniting much of south-western Rus’ under Daniel of Galicia. However, this unity was short-lived.

By 1349, the region was partitioned between the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. After the Union of Lublin in 1569, most Ukrainian lands transferred to the Crown of Poland. This period saw increased Polonisation, with many Ruthenian gentry converting to Catholicism and integrating into Polish nobility, alongside the establishment of the Ruthenian Uniate Church.

The Crimean Khanate was founded in 1441, orchestrating devastating Tatar slave raids that enslaved an estimated two million people over three centuries. Other powers like the Ottoman Empire and the Tsardom of Russia also carved out spheres of influence. Ukraine was continually divided and ruled by a multitude of external powers, a legacy of fragmentation that deeply impacted its socio-political development.

5. **The Rise and Fall of the Cossack Hetmanate**

Amidst pervasive foreign domination and the harsh enserfment of the Ruthenian peasantry, the Zaporozhian Cossacks emerged in central Ukraine. These Dnieper Cossacks and Ruthenian peasants formed a military quasi-state, the Zaporozhian Host, in the mid-17th century. This provided protection and symbolised nascent Ukrainian identity. While Poland found the Cossacks useful, their continued suppression of the Orthodox Church and severe serfdom ultimately alienated them.

This alienation culminated in the 1648 uprising led by Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky, which garnered widespread support against the Commonwealth. Khmelnytsky’s success led to the establishment of the Cossack Hetmanate, an independent Cossack state. Following a defeat in 1651, Khmelnytsky sought assistance from the Russian tsar, leading to the Pereiaslav Agreement in 1654, forming an alliance that acknowledged loyalty to the Russian monarch, a decision with long-lasting implications.

After Khmelnytsky’s death, the Hetmanate endured a devastating “Ruin” (1657–1686). The Treaty of Perpetual Peace in 1686 formally divided the Hetmanate’s lands between Russia and Poland. Further autonomy attempts, like Ivan Mazepa’s alliance with the Swedes, were crushed. By the late 18th century, Catherine the Great fully incorporated much of Central Ukraine into the Russian Empire, abolishing the Cossack Hetmanate and the Zaporozhian Sich, ending this period of limited self-governance.

6. **The Shadow of Empire: Russification and Suppressed Nationalism**

With the annexation of Crimea by Russia in 1783, a vast Ukrainian territory was opened to Russian settlement. This was accompanied by a tsarist policy of Russification, a deliberate effort to suppress the Ukrainian language and national identity. Western Ukraine, after the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth’s fall in 1795, was split between Russia and Habsburg-ruled Austria, each pursuing assimilation.

The 19th century, however, witnessed a burgeoning Ukrainian nationalism, a cultural trend aligned with romantic nationalism that sought national rebirth and social justice. A committed Ukrainian intelligentsia emerged, led by Taras Shevchenko and Mykhailo Drahomanov, championing the movement. While conditions were lenient in Austrian Galicia, Russian-controlled parts faced severe restrictions, including an outright ban on Ukrainian books in 1876.

7. **The Tumultuous Birth of Modern Ukraine: Independence Wars and Soviet Formation**

World War I plunged Ukraine into profound turmoil, with fighting persisting until late 1921. Ukrainians were initially divided, serving in both the Austro-Hungarian and the Imperial Russian armies. The collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917 ignited the Ukrainian War of Independence, a complex, multi-sided conflict involving various armies and external interventions.

An attempt to establish an independent state, the left-leaning Ukrainian People’s Republic (UNR), was declared by Mykhailo Hrushevsky. This period was plagued by extreme political and military instability, with the UNR briefly deposed by a German-backed coup and subsequent restoration efforts failing due to constant military overruns. Short-lived republics also failed to unify with the rest of Ukraine.

The protracted conflict, part of the broader Russian Civil War, devastated eastern and central Ukraine, resulting in over 1.5 million deaths and hundreds of thousands displaced, compounded by a famine in 1921. Ultimately, the conflict concluded with a partial victory for the Second Polish Republic, which annexed western Ukrainian provinces, and a more significant triumph for pro-Soviet forces. These forces led to the establishment of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, which soon became a constituent republic of the Soviet Union.

The crucible of modern Ukrainian history is marked by profound suffering, remarkable resilience, and an unwavering drive towards self-determination. From the devastating man-made famine to its pivotal role in a global conflict, and from complex integration into the Soviet system to the tumultuous journey of independence, Ukraine has consistently navigated extraordinary challenges. This segment delves into these defining modern chapters, illustrating the relentless struggle against external pressures and the persistent pursuit of a distinct national destiny, culminating in the contemporary confrontation with renewed Russian aggression.

8. **The Holodomor: A Manufactured Catastrophe**

The inter-war period in Soviet Ukraine was initially characterized by a policy of Ukrainisation, pursued by the national Communist leadership, which encouraged a national renaissance in Ukrainian culture and language. This was part of the broader Soviet-wide policy of Korenisation, aimed at promoting native peoples, their languages, and cultures within their respective republics’ governance. Concurrently, Vladimir Lenin’s New Economic Policy (NEP) introduced market socialism, successfully restoring the war-torn nation to pre-World War I production levels by the mid-1920s, with a significant portion of agricultural output originating from Ukraine. These policies even drew prominent former Ukrainian People’s Republic (UNR) figures, including Mykhailo Hrushevsky, back to Soviet Ukraine, where they contributed to the advancement of Ukrainian science and culture.

However, this brief period of relative cultural flourishing was abruptly curtailed with Joseph Stalin’s ascent to leadership and the subsequent abandonment of the NEP in what became known as the Great Break. From the late 1920s, Soviet Ukraine was integrated into a centrally planned industrialization scheme, quadrupling its industrial output throughout the 1930s. Nevertheless, Stalin harbored a deep suspicion of Ukrainian aspirations for independence, implementing severe measures to eliminate both the Ukrainian peasantry and the elite Ukrainian intellectuals and culture, perceiving them as threats to Soviet control.

As a direct consequence of Stalin’s new policies, the Ukrainian peasantry endured immense suffering under the program of collectivization of agricultural crops. Enforced by regular troops and the secret police (Cheka), collectivization led to widespread resistance, with those who resisted being arrested and deported to gulags and work camps. The imposition of unrealistic quotas, often denying collective farm members any grain until targets were met, resulted in the Holodomor, or ‘Great Famine,’ during which millions starved to death. This human-made catastrophe has been recognized by some countries as an act of genocide perpetrated by Joseph Stalin and other Soviet officials. This era also saw the Great Purge, which, while targeting Stalin’s perceived political enemies, led to the profound loss of a new generation of Ukrainian intelligentsia, now remembered as the Executed Renaissance.

9. **Ukraine’s Crucible in World War II**

World War II plunged Ukraine into another profound period of devastation and conflict. Following the invasion of Poland in September 1939, German and Soviet troops divided Polish territory, leading to Eastern Galicia and Volhynia, with their Ukrainian populations, becoming part of the Ukrainian SSR, effectively uniting the nation for the first time in history. Further territorial gains were secured in 1940 with the incorporation of northern and southern Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina, and the Hertsa region from Romania, territorial acquisitions internationally recognized by the Paris Peace Treaties of 1947. However, this unification was short-lived as German armies invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, initiating nearly four years of total war on Ukrainian soil, including the fierce Battle of Kyiv, where the city earned acclaim as a ‘Hero City’ for its desperate resistance, resulting in over 600,000 Soviet soldiers killed or captured.

After its conquest, most of the Ukrainian SSR was organized within the Reichskommissariat Ukraine, with the explicit aim of exploiting its vast resources and preparing for eventual German settlement. Initially, some western Ukrainians, who had only joined the Soviet Union in 1939, hailed the Germans as liberators; however, this perception quickly faded as the Nazis made little effort to exploit dissatisfaction with Stalinist policies. Instead, the Nazis preserved the collective-farm system, carried out genocidal policies against Jews—including an estimated 1.5 million Jewish lives taken by the Einsatzgruppen—deported millions to work in Germany, and initiated a depopulation program in preparation for German colonization. Amidst this, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), the armed forces of the underground Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), emerged in Western Ukraine, supporting the goal of an independent Ukrainian state. While at times allied with Nazi forces, from mid-1943 until the end of the war, the UPA carried out massacres of ethnic Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia, killing approximately 100,000 Polish civilians, which led to reprisals, in an attempt to create a homogeneous Ukrainian state.

The vast majority of fighting in World War II occurred on the Eastern Front, with Ukraine enduring catastrophic losses. The number of ethnic Ukrainians who fought in the ranks of the Soviet Army is estimated between 4.5 million and 7 million, while half of the pro-Soviet partisan guerrilla resistance units, totaling up to 500,000 troops by 1944, were also Ukrainian. The total losses inflicted upon the Ukrainian population during the war are estimated at 6 million, including the aforementioned Jewish victims. Of the estimated 8.6 million Soviet troop losses, 1.4 million were ethnic Ukrainians, underscoring the immense human cost borne by Ukraine in the conflict.

10. **Post-War Soviet Integration and Development**

Following the devastating war, the Ukrainian SSR was heavily damaged, with more than 700 cities and towns and 28,000 villages destroyed, necessitating immense recovery efforts. This dire situation was further exacerbated by a famine in 1946–1947, triggered by a severe drought and the wartime destruction of infrastructure, leading to the deaths of at least tens of thousands. Despite its status as a constituent republic of the Soviet Union, in 1945, the Ukrainian SSR became one of the founding members of the United Nations (UN) through a special agreement at the Yalta Conference, granting it, alongside Belarus, voting rights in the UN even though they were not independent states.

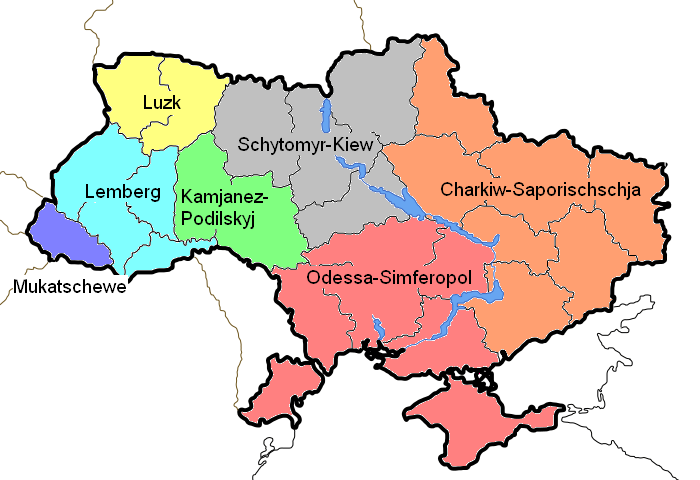

Post-war, Ukraine’s borders expanded further with the annexation of Zakarpattia, and its population became significantly more homogenized due to forced post-war population transfers, notably involving Germans and Crimean Tatars. As of January 1, 1953, Ukrainians constituted 20% of the total adult ‘special deportees,’ ranking second only to Russians. The death of Stalin in 1953 led to Nikita Khrushchev’s rise and the implementation of de-Stalinization policies. During his leadership of the Soviet Union, Crimea was formally transferred from the Russian SFSR to the Ukrainian SSR, purportedly as a friendship gift to Ukraine and for economic reasons, thereby establishing the final extension of Ukrainian territory and forming the basis for its internationally recognized borders today.

Throughout this period, numerous top positions within the Soviet Union were occupied by Ukrainians, most notably Leonid Brezhnev, who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964 to 1982. Paradoxically, it was Brezhnev and his appointee in Ukraine, Volodymyr Shcherbytsky, who presided over extensive Russification policies in Ukraine and were instrumental in repressing a new generation of Ukrainian intellectuals known as the Sixtiers. Despite these cultural suppressions, the republic had fully surpassed its pre-war levels of industry and production by 1950, quickly becoming a European leader in industrial output and a crucial center for the Soviet arms industry and high-tech research, albeit with heavy industry maintaining an outsized influence.

11. **The Cataclysm of Chernobyl**

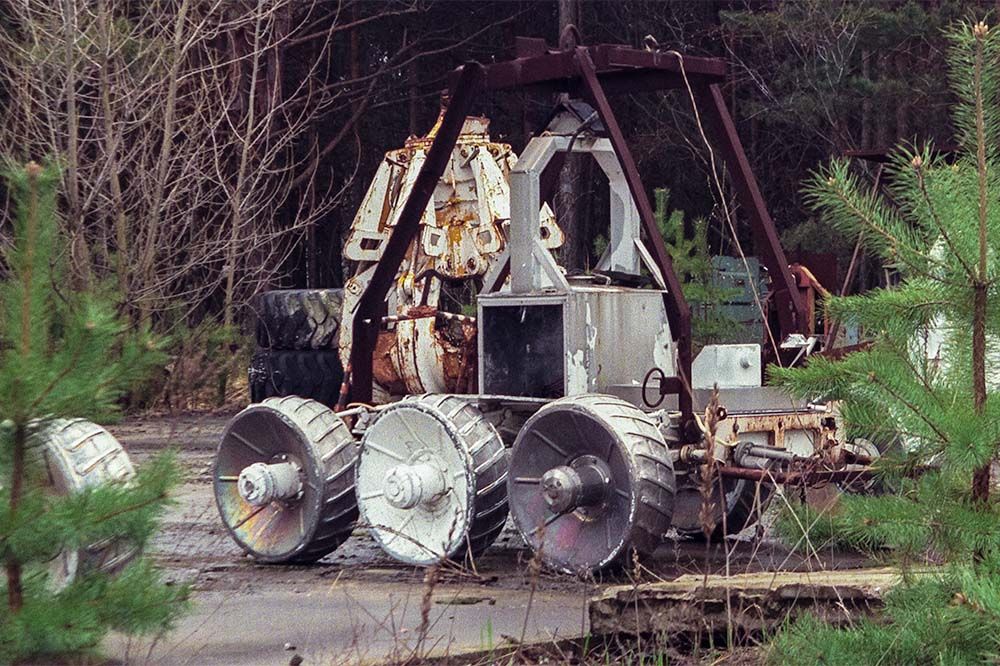

The rapid industrialization and development within Soviet Ukraine spurred significant energy demands, prompting substantial investment in hydroelectric and nuclear power projects. These initiatives, while fueling the republic’s economic and technological growth, also introduced profound risks that would ultimately lead to one of the most catastrophic environmental disasters in human history. The pursuit of ambitious energy targets and the reliance on nuclear technology underscore a critical tension between rapid industrial progress and inherent safety concerns within the Soviet system.

On April 26, 1986, this tension culminated in tragedy when a reactor in the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant exploded. This event, occurring near the city of Pripyat, resulted in the Chernobyl disaster, which is widely recognized as the worst nuclear reactor accident in history. The explosion and subsequent fire released massive quantities of radioactive material into the atmosphere, contaminating vast areas of Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia, with fallout detectable across Europe.

The Chernobyl disaster had immediate and long-term consequences, leading to widespread evacuations, severe health issues for many, and a profound environmental impact that continues to be felt decades later. The event not only exposed critical flaws in Soviet nuclear safety protocols and a culture of secrecy but also served as a stark reminder of the potential for human-made catastrophes to transcend national borders and leave an indelible mark on both the land and its people. Its legacy remains a powerful symbol of the risks associated with unchecked technological ambition and inadequate oversight.

12. **The Dawn of Independence and Economic Upheaval**

The late 1980s saw Mikhail Gorbachev’s attempts to reform the stagnating Soviet economy through policies of limited liberalization known as perestroika. While these economic reforms largely failed, the broader democratization of the Soviet Union inadvertently fueled nationalist and separatist tendencies among its diverse ethnic minorities, including Ukrainians. As part of the so-called ‘parade of sovereignties,’ the newly elected Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic adopted the Declaration of State Sovereignty of Ukraine on July 16, 1990, marking a significant step towards self-determination.

The path to full independence accelerated dramatically after a failed coup by hardline Communist leaders in Moscow, which attempted to depose Gorbachev. Seizing this critical moment, Ukraine proclaimed its outright independence on August 24, 1991, a declaration overwhelmingly approved by 92% of the Ukrainian electorate in a nationwide referendum held on December 1. Ukraine’s newly elected President, Leonid Kravchuk, subsequently signed the Belavezha Accords, which formally dissolved the Soviet Union and made Ukraine a founding member of the much looser Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), although Ukraine notably never became a full member as it did not ratify the agreement establishing the CIS. These landmark documents collectively sealed the fate of the Soviet Union, which formally ceased to exist on December 26, 1991.

Initially, Ukraine was perceived as possessing favorable economic conditions compared to other regions of the Soviet Union, despite being one of the poorer Soviet republics by the time of dissolution. However, its transition to a market economy proved exceptionally challenging, with the country experiencing a deeper economic slowdown than almost all other former Soviet Republics. During the recession between 1991 and 1999, Ukraine’s GDP plummeted by 60%, and it suffered from hyperinflation that peaked astonishingly at 10,000% in 1993. The economic situation only began to stabilize after the new national currency, the hryvnia, sharply depreciated in late 1998, partially as a fallout from the Russian debt default earlier that year. A defining legacy of the economic policies of the 1990s was the mass privatization of state property, which inadvertently created a new class of extremely powerful and wealthy individuals known as the oligarchs.

13. **Political Upheavals: Orange Revolution and Euromaidan**

Ukraine’s post-independence economic performance has generally underperformed, largely attributed to pervasive corruption and mismanagement, issues that, particularly in the 1990s, incited widespread protests and organized strikes. The country subsequently endured a series of sharp recessions, stemming from global events such as the Great Recession, and later, the domestic impact of the Russo-Ukrainian War, which began in 2014, and finally, the full-scale invasion by Russia in February 2022. Efforts to combat the COVID-19 pandemic, which emerged in 2020, were significantly hampered by low vaccination rates and, later in the pandemic, by the ongoing invasion.

From a political perspective, a defining characteristic of Ukraine’s post-independence landscape has been its division along two persistent issues: the nation’s relationship with the West versus Russia, and the more classical left-right political divide. The first two presidents, Leonid Kravchuk and Leonid Kuchma, generally attempted to balance these competing visions for Ukraine. However, subsequent leaders, Viktor Yushchenko and Viktor Yanukovych, were largely perceived as pro-Western and pro-Russian, respectively, exacerbating these underlying societal tensions.

These divisions periodically erupted into major political crises and mass demonstrations. The Orange Revolution in 2004 saw tens of thousands protest alleged election rigging in favor of Yanukovych, ultimately leading to Yushchenko’s election as president. A decade later, in the winter of 2013/2014, even larger crowds gathered on the Euromaidan in Kyiv to oppose Yanukovych’s sudden refusal to sign the European Union–Ukraine Association Agreement. By February 21, 2014, Yanukovych fled Ukraine and was subsequently removed by parliament in what is widely termed the Revolution of Dignity. Russia, however, vehemently refused to recognize the interim pro-Western government, denouncing the events as a ‘junta’ and a coup d’état sponsored by the United States, setting the stage for direct confrontation.

14. **The Resurgence of Russian Aggression**

Despite the signing of the Budapest Memorandum in 1994, an international agreement in which Ukraine relinquished its nuclear weapons in exchange for guarantees of security and territorial integrity from major powers, including Russia, the latter reacted violently to the political shifts in Ukraine. In late February and early March 2014, Russia unilaterally occupied and annexed Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula, utilizing its Black Sea Fleet based in Sevastopol, as well as the deployment of so-called ‘little green men,’ unmarked military personnel facilitating the takeover.

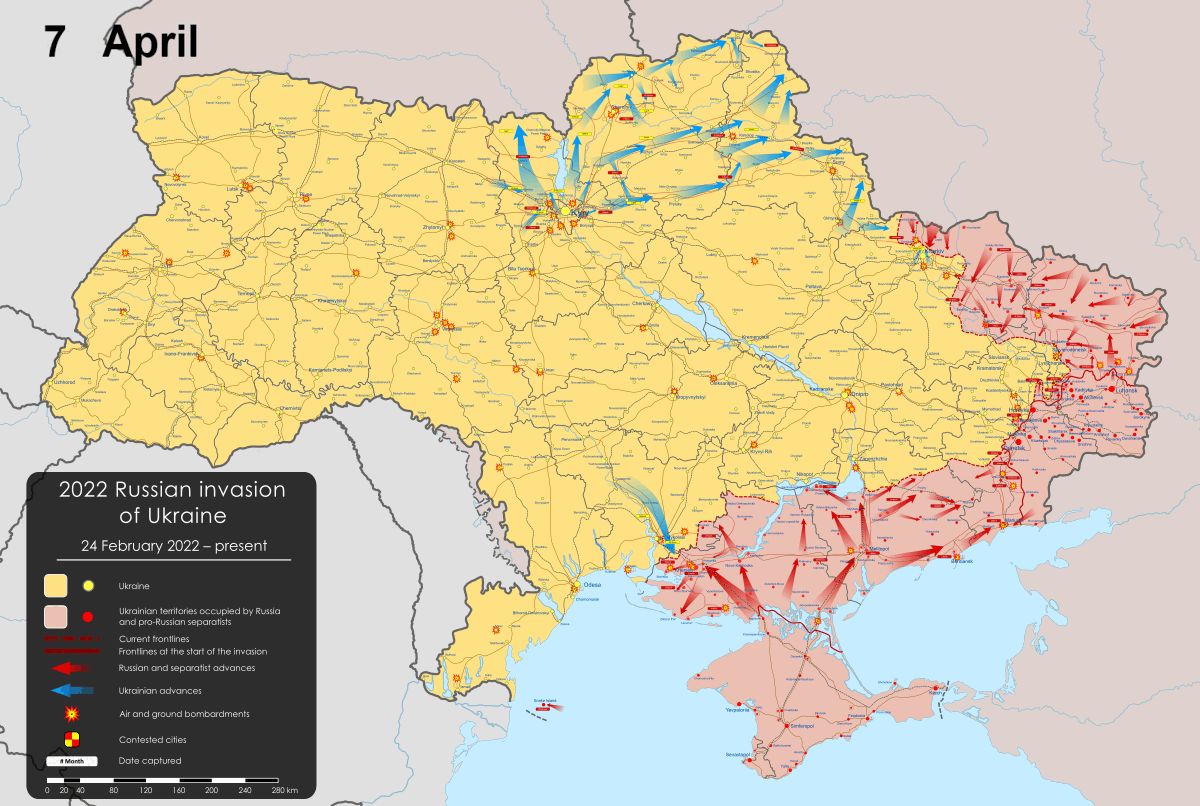

Following the successful annexation of Crimea, Russia further escalated its aggression by launching a proxy war in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine. This conflict saw the rise of Russian-backed separatists and the establishment of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic and Luhansk People’s Republic. The initial months of this conflict were characterized by fluidity, but Russian forces then launched an open invasion in Donbas on August 24, 2014. Together with the separatists, they pushed back Ukrainian troops to the frontline established in February 2015, notably after Ukrainian forces withdrew from Debaltseve.

The conflict in Donbas subsequently entered a ‘frozen’ state, characterized by intermittent fighting and a stalemated frontline, which persisted until the early hours of February 24, 2022. On this date, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, marking a dramatic and devastating escalation of the conflict. A year later, Russian troops controlled approximately 17% of Ukraine’s internationally recognized territory, including a significant majority of Luhansk Oblast (94%), Kherson Oblast (73%), Zaporizhzhia Oblast (72%), Donetsk Oblast (54%), and all of Crimea, fundamentally reshaping the geopolitical landscape of Eastern Europe.

Ukraine’s journey through its modern crucible is a testament to its enduring spirit, forged in the fires of famine, global war, and continuous struggles for freedom. Its resilience in the face of persistent external pressures and the ongoing battle for its territorial integrity underscores a profound commitment to its sovereign identity. This intricate tapestry of trials and triumphs not only defines the nation but also carries profound implications for the principles of international law, security, and the future of global stability. The saga continues, with Ukraine standing as a pivotal frontline in the broader defense of self-determination against renewed imperial ambitions.