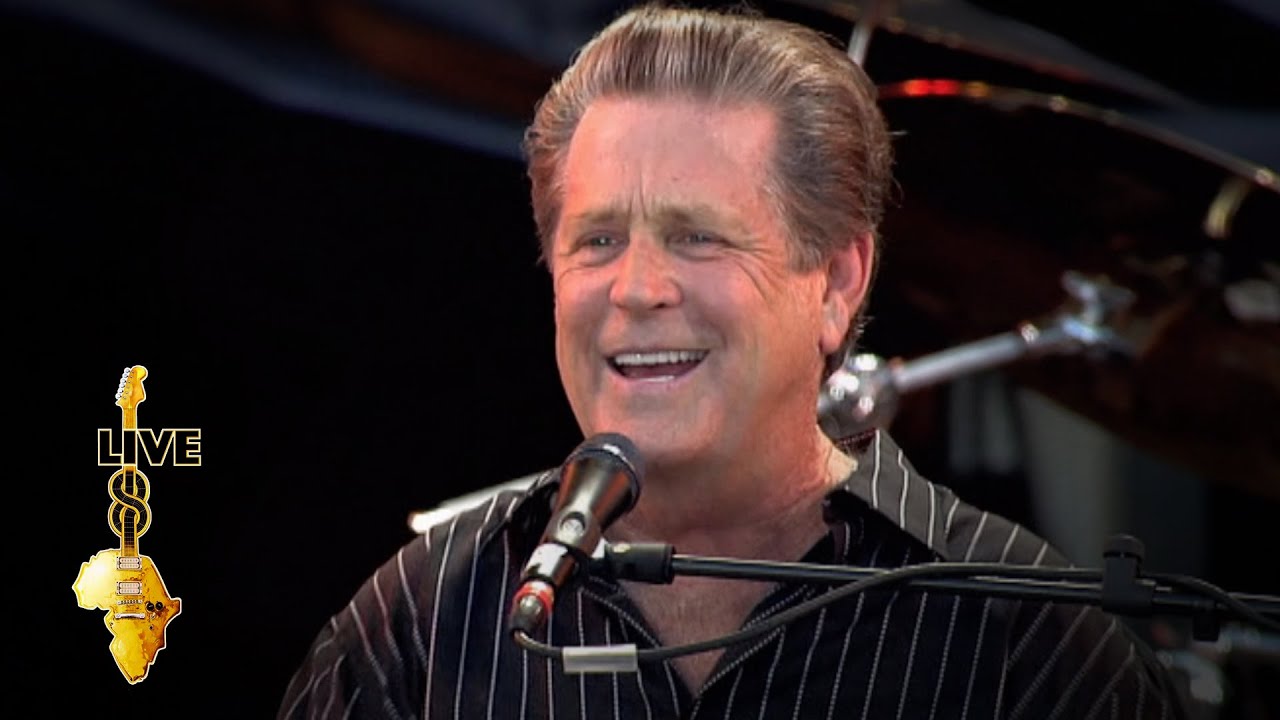

The music world pauses to reflect on the monumental life and career of Brian Douglas Wilson, the American musician, songwriter, singer, and record producer who co-founded The Beach Boys. His passing in 2025 at the age of 82 marks the end of an era, leaving behind an unparalleled legacy of innovative sound and profound cultural impact. Wilson received widespread recognition as one of the most significant musical figures of his era, celebrated for his distinctive contributions that reshaped popular music.

Wilson’s work was distinguished by its high production values, complex harmonies and orchestrations, and intricate vocal layering. His introspective or ingenuous themes resonated deeply with audiences, while his versatile head voice and falsetto became a signature element of The Beach Boys’ sound. Beyond his role as a performer, Wilson pioneered the concept of the studio as an instrument, becoming one of the first music producer auteurs and contributing to the development of numerous genres from the California sound to psychedelia.

1. **Early Life and Formative Musical Influences** Brian Douglas Wilson was born on June 20, 1942, in Inglewood, California, the eldest of Audree Neva and Murry Wilson’s three sons. The family later moved to Hawthorne, California. From a very young age, Wilson displayed an extraordinary aptitude for learning by ear, with his father recalling the infant Wilson reproducing melodies. Murry, a machinist and part-time songwriter, was instrumental in cultivating his children’s musical talents, despite Brian’s later characterization of him as “violent” and “cruel.”

Wilson’s musical education was largely self-driven and eclectic. He took accordion lessons, performed choir solos where he was declared to have perfect pitch, and immersed himself in diverse sounds. He owned *The Instruments of the Orchestra* record, listened to KFWB, absorbed R&B introduced by his brother Carl and uncle Charlie, and was deeply influenced by The Four Freshmen. He credited Bob Flanigan’s high voice with teaching him “how to sing high,” meticulously deconstructing their harmonies on the piano.

A pivotal moment occurred at 12 when his family acquired an upright piano, enabling him to spend hours mastering songs and teaching himself. While in high school, he briefly worked odd jobs but remained focused on music. For his 16th birthday, a portable two-track Wollensak tape recorder allowed him to experiment with recording group vocals and rudimentary production techniques, a precursor to his later studio innovations. His ambition to “make a name for myself […] in music” was clearly stated in a 1959 essay, foreshadowing his legendary career.

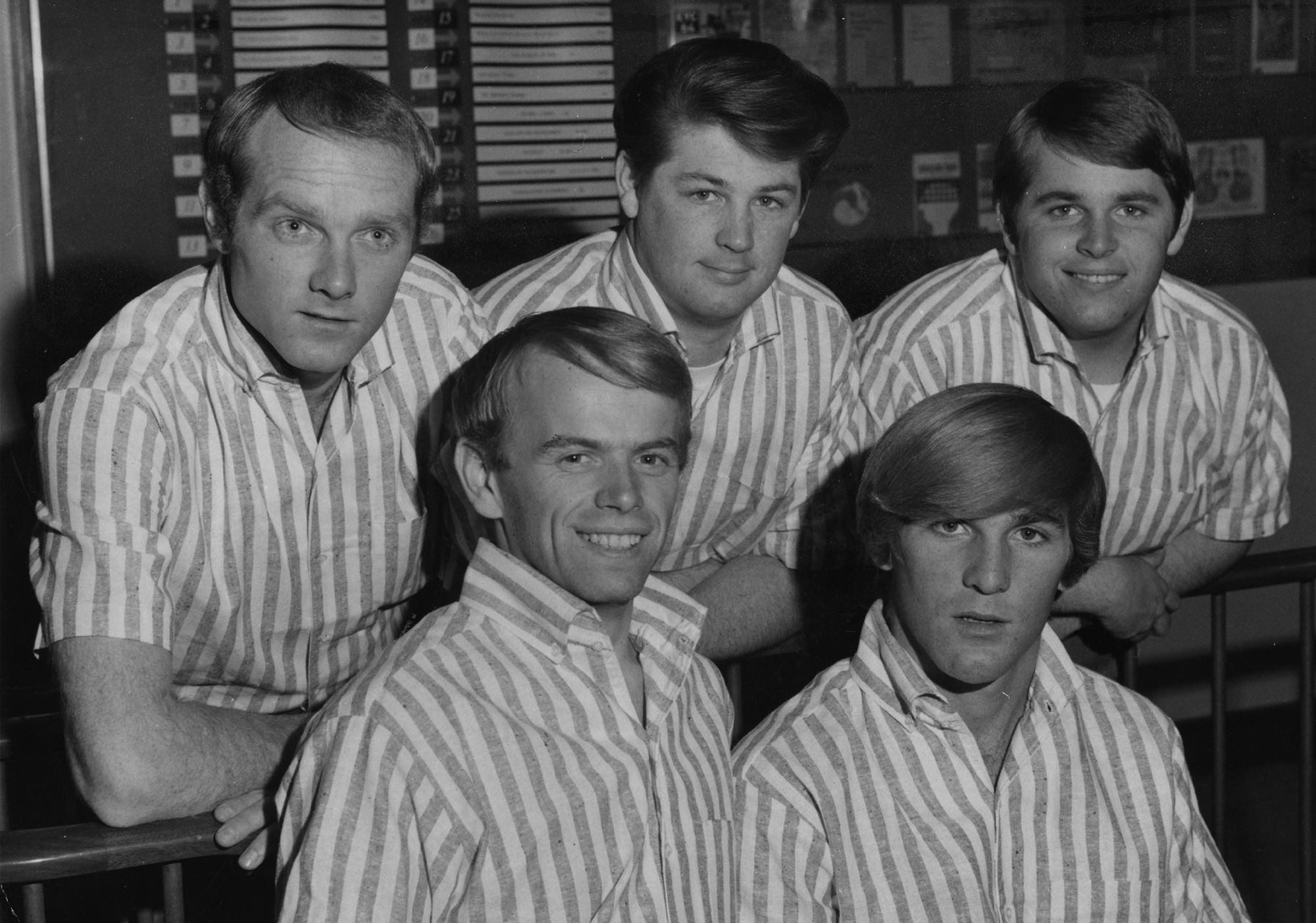

2. **The Genesis of The Beach Boys and Initial Breakthrough** The foundation of The Beach Boys was laid in the autumn of 1961 when Brian Wilson, his brothers Dennis and Carl, cousin Mike Love, and friend Al Jardine formed “the Pendletones.” Dennis, the sole surfer, provided Brian with the “jargon” for their surf-themed songs. Their first co-written original, “Surfin’,” captured California’s burgeoning surf culture and, produced by Hite and Dorinda Morgan on Candix Records, became a local hit, reaching number 75 nationally. Candix Records subsequently renamed them “the Beach Boys.”

Their major live debut on New Year’s Eve, 1961, saw Brian quickly learn to play an electric bass, prompting Jardine to switch to rhythm guitar. However, Candix Records’ financial troubles led to the sale of their master recordings and the termination of their contract. Undeterred, Brian, the creative engine, collaborated with local musician Gary Usher to produce demos for new tracks like “409” and “Surfin’ Safari.”

These demos proved crucial, persuading Capitol Records to release them as a single. This double-sided national hit propelled The Beach Boys into the mainstream, setting the stage for their rapid ascent. It cemented Brian Wilson’s role not just as a songwriter, but as a driving force in the band’s sound and identity, laying the groundwork for their subsequent commercial and artistic triumphs.

3. **Ascending Producer and Independent Vision** In 1962, Brian Wilson’s artistic control became evident when The Beach Boys signed with Capitol Records. He insisted on recording outside the label’s basement studios, securing permission for external sessions funded by the band while retaining recording rights. Crucially, Wilson gained production control over their debut album, *Surfin’ Safari*, though initially uncredited, marking an early assertion of his visionary approach.

Inspired by Phil Spector, Wilson saw himself as a “behind-the-scenes man” aiming to emulate Spector’s career. He actively pursued this vision by collaborating with Gary Usher on numerous songs and producing records for local talent, albeit without immediate commercial breakthroughs. His first uncredited production outside The Beach Boys was Rachel and the Revolvers’ “The Revo-Lution.” Official credit came in October 1962 on “The Surfer Moon” by Bob & Sheri, released by Murry’s short-lived Safari Records, solidifying Brian’s burgeoning role as a multi-faceted musical architect.

Wilson’s dedication to studio work became paramount during the production of *Surfin’ U.S.A.* (1963), where he limited public appearances to prioritize recording. The album’s success, reaching number two on Billboard, cemented The Beach Boys as a major act. Defying Capitol and his father’s disapproval, Wilson collaborated with Jan and Dean, co-writing “Surf City,” which topped U.S. charts in July 1963 and revitalized the duo’s career. This period, including his work with “the Honeys” and full production credit on *Surfer Girl* and *Little Deuce Coupe*, showcased his independent spirit and growing confidence as a hitmaker and entrepreneurial producer.

4. **International Acclaim and the Pressures of Stardom** The year 1964 brought The Beach Boys international acclaim but also intensified Brian Wilson’s psychological strain. As he toured globally and produced albums like *Shut Down Volume 2* and *All Summer Long*, the band dismissed Murry Wilson as their manager after a particularly stressful tour. The arrival of Beatlemania in the U.S. deeply concerned Wilson, who felt their supremacy threatened. He responded by “stepping on the gas,” leading to “I Get Around,” their first U.S. number-one hit, marking an unofficial rivalry with The Beatles.

Despite the success, Wilson felt the immense weight of his “Mr Everything” role. He began distancing himself from surf-themed material, aiming to “produce a sound that teens dig, and that can be applied to any theme.” He felt “mentally drained,” unable to rest, and concerned about the group’s “business operations” and record quality under constant pressure. This mounting stress took a severe toll on his well-being.

The strain culminated in a nervous breakdown on December 23, 1964, during a flight to Houston for a tour. Sobs of stress over his recent marriage led to his replacement by Glen Campbell for the remainder of the tour, marking what Wilson called “the first of a series of three breakdowns.” This pivotal event prompted his decision in January 1965 to withdraw from touring permanently, freeing him to focus exclusively on studio work, a move that would profoundly alter The Beach Boys’ trajectory and usher in an unprecedented era of studio innovation.

5. **The Revolutionary Era of ‘Pet Sounds’** Freed from touring, Brian Wilson immersed himself in studio experimentation, cultivating a new social circle independent of familial oversight by late 1964. Talent agent Loren Schwartz introduced him to philosophy, world religions, and, controversially, marijuana and hashish, influencing his artistic output and contributing to marital tensions. His first song composed under marijuana’s influence was “Please Let Me Wonder” (1965), signaling a shift in his creative process.

In 1965, Wilson’s musical ambitions soared with *The Beach Boys Today!* and *Summer Days (And Summer Nights!!)*. Early in the year, he experienced his first LSD trip, describing it as a transformative experience during which he composed portions of “California Girls.” He considered the backing track session for this song his “favorite” and its opening orchestral section “the greatest piece of music that I’ve ever written,” though he later attributed persistent paranoia to his LSD use.

After reconciling with Marilyn and relocating to Beverly Hills, Wilson experienced an “unexpected surge of creativity,” fueled by heavy drug use which made him “really introspective.” Over five intense months, he planned an album to elevate his music to “a spiritual level,” leading to *Pet Sounds*. Collaborating with lyricist Tony Asher in December 1965, Wilson produced most of the album between January and April 1966, primarily using session musicians for backing tracks and bandmates for vocals. He highlighted “Let’s Go Away for Awhile” as his “most satisfying piece of music” and “Caroline, No” as “probably the best [song] I’ve ever written,” which was released as his first solo-credited single.

Despite critical acclaim, *Pet Sounds’* failure to reach number one on the charts “mortified” Wilson. Marilyn recalled, “When it wasn’t received by the public the way he thought it would be received, it made him hold back.” This disappointment, however, did not deter his creative drive; as Marilyn stated, “he didn’t stop. He couldn’t stop. He needed to create more,” setting the stage for his next ambitious, yet ultimately unfinished, project.

6. **”Good Vibrations,” the Ambitions of ‘Smile,’ and Worsening Mental Condition** The period following *Pet Sounds* saw Brian Wilson achieve unprecedented commercial triumph with “Good Vibrations,” topping U.S. charts in December 1966. This success coincided with a public relations campaign by Derek Taylor, The Beatles’ former press officer, promoting Wilson as a “genius.” While the campaign bolstered *Pet Sounds’* critical reception in the UK, Wilson later expressed resentment toward this label, feeling it imposed an unsustainable burden of unrealistic expectations for his subsequent work.

Wilson then embarked on *Smile*, intended as the follow-up to *Pet Sounds*, famously touted as a “teenage symphony to God.” As his creative endeavors intensified, his social circle expanded, influencing both his business and creative decisions. Van Dyke Parks described this environment as “self-interested people pulling him in various directions.”

The pressures took a severe toll on Wilson’s mental well-being. A 1967 documentary visitor characterized his home as “a playpen of irresponsible people.” Late 1966 marked a critical turning point with erratic behavior during “Fire” sessions, signaling a significant decline. This contributed to *Smile* remaining unfinished, leading Wilson to relocate to Bel Air, constructing a home studio, and increasing his isolation.