The narrative of American expansion is interwoven with tales of struggle and profound conviction, few more compelling than that of Lawrence, Kansas. This vibrant college town, now home to the University of Kansas and Haskell Indian Nations University with a 2020 population of 94,934, belies a tumultuous past etched into the very fabric of its identity. Situated strategically along Interstate 70, between the Kansas and Wakarusa Rivers, Lawrence emerged not from economic opportunity but from the fiery crucible of a nation divided.

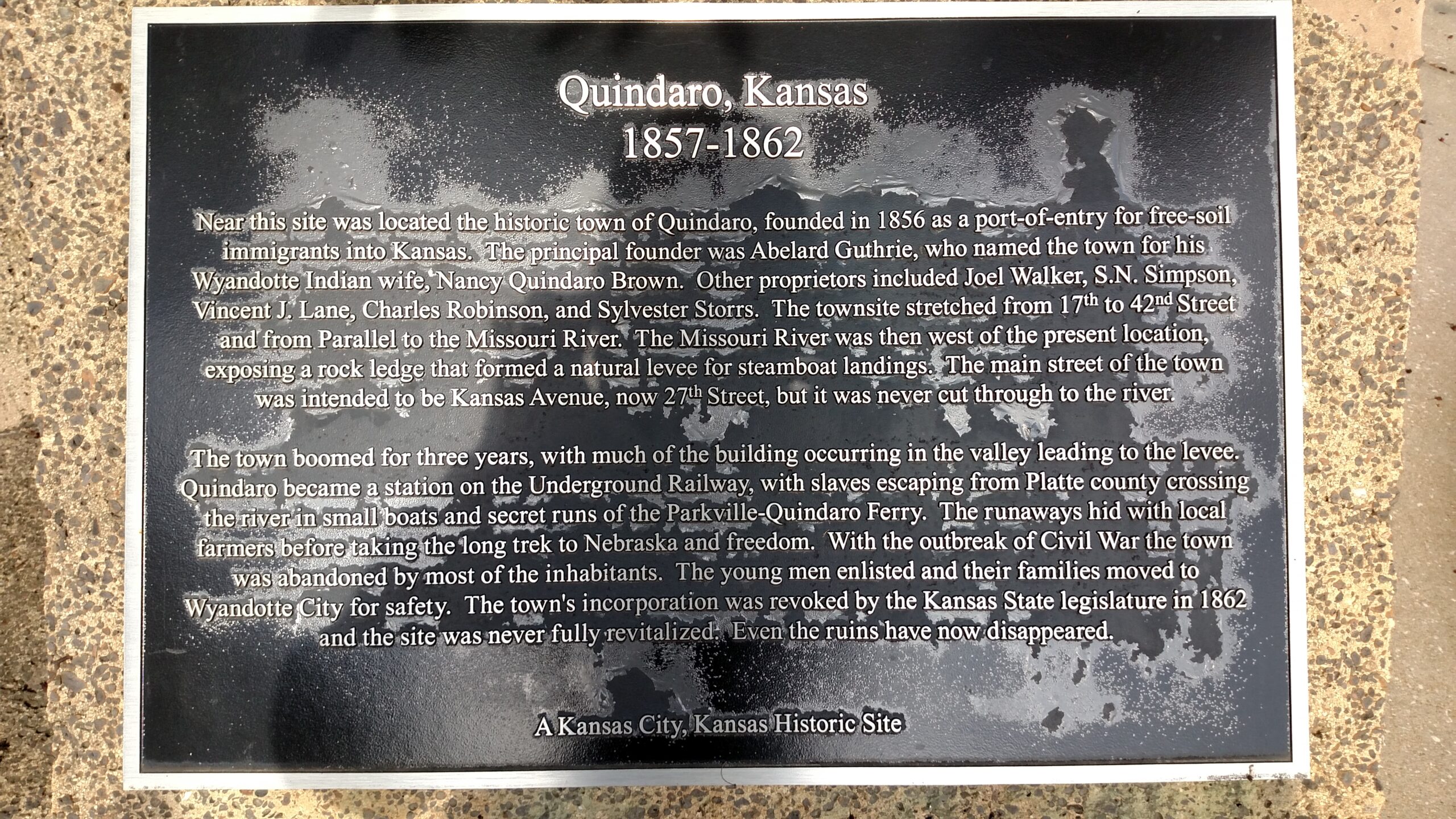

Its founding was “strictly for political reasons,” inextricably linked to the fierce national debate over slavery in the mid-19th century. Lawrence became a focal point in the “Bleeding Kansas” period, a brutal ideological and physical conflict that served as a grim prelude to the American Civil War. Here, the principles of liberty and self-determination were fiercely contested, transforming the nascent settlement into a battleground for the future of the Union itself.

This article delves into Lawrence’s foundational years, exploring the legislative catalysts, the courageous pioneers, and the harrowing conflicts that forged its character. We will examine how a community, against overwhelming odds, carved out a sanctuary for freedom, shaping a legacy that continues to define Lawrence as a beacon of progressive thought and educational excellence. It’s a testament to unwavering conviction and the powerful resilience of a community determined to build a future rooted in anti-slavery ideals.

1. **The Genesis of a Free-State Ideal: The Kansas-Nebraska Act and Popular Sovereignty**: The very foundation of Lawrence, Kansas, directly stems from the intense national debate surrounding slavery’s expansion in the mid-19th century. At its core was “popular sovereignty,” a concept pushed by Northern Democrats like Senators Lewis Cass and Stephen A. Douglas. This doctrine proposed that citizens of new territories, rather than federal politicians, should directly determine whether slavery would be legal in their lands. Proponents hailed it as a democratic solution, empowering local populations with a direct say in a momentous issue.

However, this idea was vehemently opposed in the North, where it was derisively termed “squatter sovereignty.” The critical legislation, Douglas’s Kansas–Nebraska Act, passed by Congress in 1854, cemented popular sovereignty for the territories. Crucially, this act repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had prohibited slavery north of 36°30′ parallel, thus opening Kansas and Nebraska to its possibility. This legislative move ignited a national firestorm, dismantling a long-standing agreement that had previously maintained a delicate balance.

The Act’s passage sparked “despondency all over the north,” as many viewed it as “equivalent to making Kansas a slave state.” This fear was largely justified; nearby Missouri was a slave state, and it was widely assumed early Kansas settlers would come from there, bringing slavery with them. The Kansas–Nebraska Act, therefore, galvanized antislavery forces, uniting them into a powerful movement, eventually institutionalized as the Republican Party. This pivotal moment set the stage for free-state migration to Kansas, driven by a determination to actively counter the expansion of slavery and lay the groundwork for a free-state future.

2. **Pioneering the Future: The New England Emigrant Aid Company’s Vision**: To combat the threat of Kansas becoming a slave state, a robust counter-movement emerged, spearheaded by the New England Emigrant Aid Company (NEEAC). Led by figures such as Eli Thayer, a Republican Congressman, and Amos A. Lawrence, a prominent Republican abolitionist and businessman, the NEEAC had a clear, audacious goal: to populate Kansas Territory with antislavery settlers. Their vision was to ensure a decisive free-state vote when the time came for the territory to determine its stance on slavery, thereby securing freedom through democratic means.

The NEEAC acted swiftly. By June 1854, Dr. Charles Robinson and Mr. Charles H. Branscomb were dispatched to Kansas to scout for an ideal colonial site. Robinson, already familiar with the territory, had noted the strategic beauty of Hogback Ridge, later named Mount Oread. His previous observations proved instrumental in the final selection, highlighting the importance of foresight in their ambitious endeavor.

The chosen location near Hogback Ridge offered significant advantages. It was strategically positioned along the Oregon Trail, and also intersected with the Santa Fe and 1846 Military Trails, ensuring accessibility. Furthermore, it was identified as the “first desirable location where emigrant Indians had ceded their land rights,” making it readily available for settlement. This meticulous planning by the NEEAC and its agents underscored their systematic approach to securing Kansas for the free-state cause, translating political ideals into a tangible, strategic settlement.

3. **Laying the Foundations: Early Settlers, Topography, and the Naming of Lawrence**: The practical task of establishing the colony began with the NEEAC’s first settlers. Though a cholera outbreak reduced their initial numbers, a resolute group of 29 men, known as the “pioneer colony,” volunteered for the journey. Led by Branscomb, they departed Boston on July 17, 1854, arriving in Kansas Territory near the end of July. Their first meal on Hogback Ridge on August 1st marked the symbolic and literal birth of the settlement, soon to be renamed Mount Oread after a Massachusetts institute.

Immediately, this pioneering group began establishing their city between Mount Oread and the Kansas River, approximately where Massachusetts Street now lies. They were soon joined by a second, larger party of around 114 people, including women and children, led by Robinson and Samuel C. Pomeroy. Subsequent settler groups arrived in October and December, steadily increasing the population, though some, disappointed by the harsh conditions, eventually returned to New England.

The nascent community rapidly moved to formalize its structure. By September 18, colonists had established a “voluntary municipal government,” adopting a constitution by September 20 that included prohibitionary Maine law principles. Initially called Wakarusa or New Boston, the name “Lawrence” gained favor, honoring Amos A. Lawrence, a key abolitionist funder of the Emigrant Aid Company. This choice proved financially astute, encouraging further monetary support, and was politically neutral, having “no bad odor attached to it in any part of the Union.” On October 1, 1854, “Lawrence” was formally approved as the city’s name, cementing its identity and anti-slavery commitment.

4. **Kansas Statehood and the American Civil War: A Nation Divided, A State Forged**: The arduous struggles of the ‘Bleeding Kansas’ era finally culminated in a decisive moment for the territory. On October 4, 1859, the Wyandotte Constitution, which enshrined free-state principles, was approved by a significant referendum vote of 10,421 to 5,530. This victory signaled a clear end to the pro-slavery forces’ bid to control Kansas, paving the way for its official entry into the Union. Following its approval by the U.S. Congress, Kansas proudly achieved statehood as a free state on January 29, 1861.

However, this hard-won triumph for freedom arrived concurrently with a cataclysmic national event: the outbreak of the American Civil War. Kansas’s admission was notably facilitated by the departure of seceding states’ pro-slavery congressmen, whose previous obstruction had long stalled the process. Thus, the very moment Kansas joined the Union as a beacon of liberty, the nation plunged into its deepest conflict, ensuring the state’s early years would remain steeped in the fight for freedom.

During this tumultuous war period, Lawrence rapidly transformed into a vital stronghold for Unionist irregulars, particularly the infamous Jayhawker guerrilla units. These groups, often referred to as ‘Red Legs,’ operated under the leadership of figures such as James Lane, James Montgomery, and ‘Doc’ Jennison. Their operations included frequent raids into parts of western Missouri, where they engaged in acts of reprisal, stealing goods and burning down farms.

It became a widely held belief among Southerners that the vast quantities of goods and plunder seized by these Jayhawkers were routinely stored within Lawrence. This perception, whether entirely accurate or not, solidified Lawrence’s image in the eyes of Confederate sympathizers as a primary target, further embroiling the city in the brutal border warfare that characterized the conflict along the Kansas-Missouri frontier.

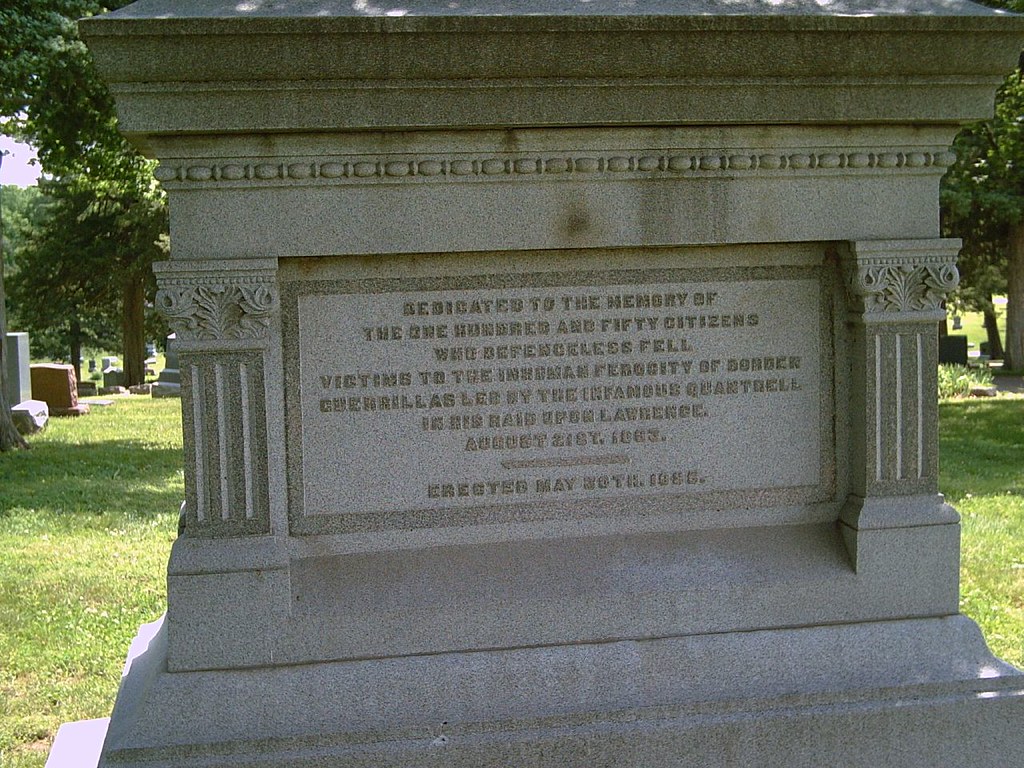

5. **Quantrill’s Raid: The Lawrence Massacre of 1863**: The lingering animosity and the city’s reputation as a Jayhawker haven led to one of the most brutal and devastating attacks in American history. On the morning of August 21, 1863, Lawrence was suddenly and violently attacked by William Quantrill and hundreds of his irregular Confederate raiders. This surprise assault, born of vengeful intent, descended upon a city largely unprepared for such a concentrated and merciless onslaught, leaving an indelible scar on its collective memory.

The scale of destruction was catastrophic, transforming the vibrant free-state town into a scene of utter desolation. Quantrill’s men systematically burned most of Lawrence’s houses and businesses to the ground. The human cost was even more horrific: between 150 and 200 men and boys were murdered in cold blood, leaving an agonizing legacy of 80 widows and 250 orphans. The financial toll was equally staggering, with an estimated $2,000,000 worth of property destroyed, an amount equivalent to over $51 million in 2024, highlighting the immense economic devastation inflicted upon the community.

Amidst the widespread destruction, the Plymouth Congregational Church in Lawrence remarkably survived the inferno, a testament to its resilience, although a number of its dedicated members tragically lost their lives, and its historical records were destroyed. This attack, a stark reminder of the Civil War’s brutal realities, aimed not just to punish Lawrence, but to break its spirit and eliminate its influence as a beacon of abolitionism.

In the immediate aftermath of the massacre, the survivors, alongside their steadfast Unionist allies, courageously began the daunting task of cleaning up the damage and restoring their shattered settlement. A harsh Kansas winter temporarily forced a pause in their efforts, but rebuilding efforts recommenced with a fierce determination in 1864. Richard Cordley, a contemporary observer, famously described this intense commitment to reconstruction as akin to ‘a religious obligation,’ underscoring the community’s unwavering resolve.

The trauma of 1863 left Lawrence’s citizens understandably on edge, with Cordley noting, ‘Rumors [of guerrilla attacks] were thick and the people [of Lawrence] were particularly sensitive to them.’ To counter future threats, citizens promptly organized themselves into local companies to protect the city. The federal government also responded by erecting several military posts on Mount Oread, including Camp Ewing, Camp Lookout, and Fort Ulysses, to maintain a vigilant guard over the city. Fortunately, no further major attacks were made on Lawrence, and these vital defensive installations were eventually abandoned and dismantled after the war’s conclusion.

6. **From the Ashes: Post-War Reconstruction and the Founding of the University of Kansas**: Amidst the profound trauma and the monumental task of reconstruction following the Quantrill’s Raid, a new vision for Lawrence began to take shape, focused on intellectual and cultural growth. Early attempts to establish a university in Kansas had been made as far back as 1855, but it was only after Kansas achieved statehood in 1861 that these aspirations began to bear fruit. The Kansas Constitution itself, upon statehood, included a crucial provision for a state university, laying the legislative groundwork for future academic excellence.

The question of the university’s precise location became a subject of heated debate between 1861 and 1863, with Lawrence, Manhattan, and Emporia all vying for the prestigious honor. Manhattan eventually secured the designation as the site of the state’s land-grant college on January 13, 1863, narrowing the choice to just Lawrence and Emporia. This pivotal moment intensified the competition, with each city highlighting its unique advantages.

Lawrence presented a compelling case, offering a substantial financial contribution of $10,000, along with interest, generously donated by Amos Lawrence, the city’s namesake. Furthermore, the city pledged 40 acres of land specifically for the university’s campus. These significant material contributions held “great weight” with the state legislature, proving instrumental in the final decision. In a truly narrow victory, Lawrence ultimately triumphed over Emporia by a single vote, securing its destiny as a major educational hub.

As a direct result of this legislative decision and the community’s steadfast efforts, the University of Kansas (KU) proudly opened its doors to students in 1866. Its establishment served as a powerful symbol of rebirth and a profound commitment to education in a city that had endured such immense hardship. The university quickly grew to become a cornerstone of Lawrence’s identity, attracting scholars and students and fostering an environment of intellectual inquiry.

Complementing this educational growth, critical infrastructure began to connect Lawrence to the wider world. The first railroad to reach Lawrence, originating from Kansas City, was completed in 1864, with the inaugural train arriving on November 28 of that year. This vital link, surveyed by the Union Pacific Railway, Eastern Division, significantly boosted the city’s economic prospects. Further expansion saw the first train to operate in Kansas south of the Kansas River crossing into Lawrence on November 1, 1867, solidifying the city’s role as a regional transportation nexus.

7. **Powering Progress: Industrial Development and the Bowersock Dam**: The burgeoning city of Lawrence, eager to capitalize on its strategic location and growing population, soon faced a critical challenge: a reliable energy source to fuel its industrial ambitions. In the early 1870s, facing an acute energy crisis, the city embarked on an ambitious project, contracting with Orlando Darling to construct a dam across the Kansas River. This undertaking was designed to harness the river’s power and provide the much-needed energy for Lawrence’s burgeoning industries.

The project, however, was not without its trials. In the winter of 1873, an unforgiving ice jam broke loose, causing significant damage to a portion of the incomplete dam. This setback proved too much for Darling, who subsequently resigned and departed Lawrence shortly thereafter. Despite this initial disappointment, the vision for a powered city remained, and the local determination to see the project through persisted.

The Lawrence Land & Water Company stepped in to continue the work, successfully completing the dam later that same year. Yet, the challenges continued, as damage from seasonal floods plagued the company year after year. The persistent maintenance issues and financial strain eventually led the company into receivership in 1878. It was then purchased by James H. Gower and his son-in-law, Justin DeWitt Bowersock, who would leave an enduring mark on Lawrence’s industrial landscape.

It was only after Bowersock assumed direct responsibility for the extensive dam repairs in 1879 that the regular and costly damage to the structure finally ceased. Under his astute management and engineering oversight, the dam was stabilized and made operational, providing consistent power. The Bowersock Dam, which proudly remains the only hydropower dam in the state of Kansas, played a pivotal role in Lawrence’s transformation, helping it establish itself as a significant industrial city, a far cry from its early days as a political battleground.

While the dam eventually closed in 1968, its importance to the city’s identity and energy needs led to its reopening in 1977. This revitalization was aided by the city, which had plans to construct a new city hall adjacent to the Bowersock Plant, demonstrating a clear commitment to integrating its industrial heritage with modern municipal development. Beyond this monumental project, Lawrence also saw other early industrial endeavors, including the construction of the first wind-powered mill in Kansas in 1863 near 9th Street and Emery Road. Though partially destroyed during Quantrill’s Raid, it was rebuilt in 1864 at a cost of $9,700, continuing to operate until July 1885 before being tragically consumed by fire in 1905, marking the end of an era.

8. **A Beacon for Indigenous Education: The Establishment of Haskell Indian Nations University**: Lawrence’s commitment to education expanded significantly with the establishment of another vital institution, one with a unique mission. In 1884, the United States Indian Industrial Training School opened its doors in Lawrence. This Native American Boarding School was founded with the explicit goal of assimilation, aiming to provide vocational and practical training to Indigenous students from various tribes across the nation. It represented a complex chapter in American history, reflecting prevailing policies of the era.

Responding to evolving educational needs, the school expanded its offerings in 1885 to include academic training, moving beyond purely vocational instruction. A commercial department, notably equipped with five typewriters, was opened, marking a significant milestone as it initiated the very first touch-typing class in Kansas. This forward-thinking addition underscored a broader commitment to preparing students for a changing economic landscape and administrative roles.

The institution underwent a name change in 1887, becoming the Haskell Institute, a tribute to Dudley Haskell, a legislator instrumental in securing the school’s location in Lawrence. Over the years, Haskell gained considerable renown, particularly for its athletic prowess, earning the formidable nickname ‘Powerhouse of the West.’ Its teams achieved impressive victories over collegiate powerhouses like Oklahoma A&M, Kansas State, Texas, and Nebraska, and notably, the legendary Olympian Jim Thorpe was among its distinguished graduates, further cementing its athletic legacy.

High school classes were first offered in 1927, providing a comprehensive education path for students. The last high school class graduated in 1965, as the school progressively transitioned its focus towards post-high school education, adapting to the changing educational landscape. This evolution continued with the school being renamed Haskell Indian Junior College in 1970, and finally, reflecting its elevated academic standing and broadened mission, it became Haskell Indian Nations University in 1993, a testament to its enduring legacy as a premier institution for Indigenous education.

9. **Charting the 20th Century: Milestones and Modern Foundations**: The 20th century ushered in a new era of growth and transformation for Lawrence, marked by significant institutional development, natural challenges, and cultural moments. In 1888, the city saw the opening of Watkins National Bank at 11th and Massachusetts, founded by the prominent Jabez B. Watkins. This financial institution served the community until 1929, becoming a fixture of downtown commerce.

Following its closure, Watkins’s widow, Elizabeth, a dedicated philanthropist who also funded buildings for the University of Kansas and two local hospitals, generously donated the bank building to the city for use as its city hall. This act of civic generosity provided a central hub for municipal governance for decades. In 1970, with the construction of a new city hall, the historic bank building underwent extensive renovations and reopened in 1975 as the Elizabeth M. Watkins Community Museum, preserving a piece of Lawrence’s architectural and social history for future generations.

Despite its progressive development, Lawrence remained susceptible to the formidable power of nature, particularly devastating floods. The Kansas River, a lifeblood for the city, swelled dramatically in 1903, causing widespread property damage, especially in North Lawrence, with waters reaching as high as 27 feet. Even today, water marks on buildings, such as at TeePee Junction and Burcham Park, serve as silent reminders of this historic deluge. The city would face further major floods in 1951, when water levels rose over 30 feet, and again in 1993, though by then, an improved reservoir and levee system minimized damage compared to previous events.

Presidential visits also punctuated Lawrence’s 20th-century timeline, highlighting its growing national recognition. Theodore Roosevelt made a brief stop in 1903 on his way to Manhattan, delivering a speech and dedicating a fountain at 9th & New Hampshire, which was later relocated to South Park. He returned in 1910 after dedicating the John Brown State Historical Site in Osawatomie, where he delivered a notable speech on his ‘New Nationalism’ philosophy, linking Lawrence to broader national political discourse.

Urban infrastructure and entertainment evolved rapidly. The Lawrence Street Railway Company, established in 1871, offered early public transport with horse- and mule-pulled streetcars along Massachusetts Street. However, the 1903 flood damaged the Kansas River bridge, making it unsafe for streetcars and leading to the company’s closure. A new streetcar system was eventually implemented in 1909, operating until 1935, while a memorable wooden roller coaster, Casey’s Coaster, delighted visitors in Woodland Park from 1909 to the 1920s. Healthcare also advanced, with Lawrence Memorial Hospital opening in 1921 with 50 beds, expanding to 200 by 1980.

The city’s 75th anniversary in 1929 was a moment for reflection and dedication, marked by the unveiling of Founder’s Rock, also known as the Shunganunga Boulder, which honors the Emigrant Aid Society’s pioneering settlers. This year also saw the dedication of the Lawrence Municipal Airport on October 14, a clear sign of the city’s forward-looking spirit. A unique chapter unfolded during World War II, when German and Italian prisoners of war were transported to Kansas in 1943 to alleviate wartime labor shortages on farms. Lawrence hosted a smaller branch camp near 11th & Haskell Avenue, near the railroad tracks, which operated until the end of 1945, contributing to the national war effort in an unexpected way.

Post-war, local entrepreneurship flourished, with Gilbert Francis and his son George opening Francis Sporting Goods downtown in 1947, initially specializing in fishing and hunting gear. After decades of serving the community, the retail business within Lawrence’s Downtown Historic District closed in November 2014, allowing the Francis family to pivot their focus to supplying uniforms and equipment to teams. A more dramatic turn came in the early 1980s when Lawrence captured international attention as the filming location for the television movie ‘The Day After.’ This powerful and unsettling film depicted the aftermath of a nuclear war in the United States, with hundreds of local residents participating as extras and in speaking roles. The movie brought a fictional but deeply impactful narrative to life against the backdrop of Lawrence, sparking a global conversation about the horrors of nuclear conflict.

10. **Contemporary Lawrence: Navigating Growth and Embracing the Future**: As Lawrence progressed into the 21st century, its identity as a vibrant college town, steeped in a rich and often tumultuous history, continued to evolve. The dynamic interplay between its esteemed educational institutions—the University of Kansas and Haskell Indian Nations University—its deep commitment to historical preservation, and the collective aspirations of its community has largely defined its trajectory in recent decades. The city consistently strives to balance its cherished heritage with the demands of modern development and growth.

In 2020, a comprehensive report commissioned by the Lawrence City Council brought into sharp focus critical economic considerations for the city’s future. The report’s findings were stark, concluding that Lawrence urgently needed to “promote a vital expansion or risk turning into an unaffordable albatross.” This assessment underscored a pressing need for strategic economic development to ensure long-term stability and prosperity for its residents.

The analysis further emphasized a crucial imperative: the city must attract “more kinds of businesses” to diversify its economic base. The warning was clear: without such diversification, Lawrence could potentially “become a bedroom community that’s not affordable for people who don’t commute elsewhere.” This forward-looking assessment highlights the ongoing challenge of carefully balancing growth, maintaining affordability for its diverse population, and preserving its distinctive character as a hub of progressive thought and educational excellence.

Lawrence today stands as a powerful testament to its past—a city quite literally forged in the fires of conflict and defined by its unwavering resilience. Yet, it remains a forward-looking community, continually embracing the future. Its vibrant atmosphere, dynamically fueled by the intellectual energy and cultural diversity brought by the University of Kansas and Haskell Indian Nations University, continues to be a significant draw. This ensures Lawrence’s ongoing importance and enduring legacy as a pivotal cultural, educational, and historical center within the heart of Kansas, a place where history resonates deeply with contemporary life.