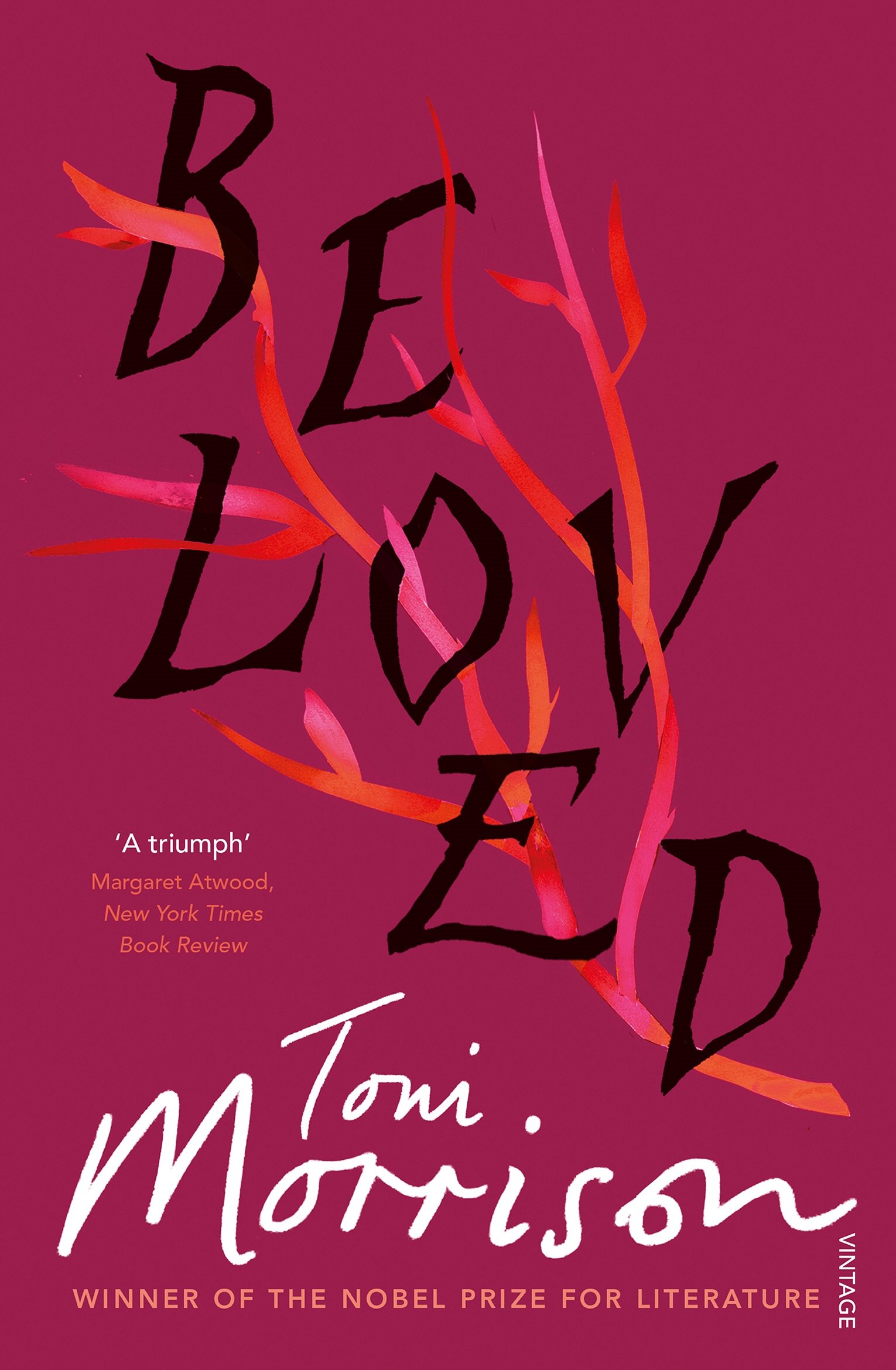

Toni Morrison’s “Beloved,” a monumental 1987 novel, stands as a searing testament to the enduring scars of slavery and the profound human struggle for freedom, identity, and healing in its wake. Recognized with the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction a year after its publication and later ranked by The New York Times as the best work of American fiction from 1981 to 2006, its impact on the literary landscape is undeniable. The novel plunges readers into the harrowing reality of a post-Civil War America, where the physical chains of bondage may have been broken, but the psychological and spiritual reverberations continued to haunt individuals and communities.

This in-depth exploration will navigate the intricate layers of “Beloved,” unraveling its historical tapestry, dissecting its unforgettable characters, and examining the pervasive themes that resonate with such powerful authenticity. We will embark on a journey through the narrative, from its real-life inspirations to the spectral presence that defines its core, understanding how Morrison meticulously crafted a world where past and present are inextricably linked, and where the fight for selfhood is a continuous, agonizing process.

As we delve into the initial seven dimensions of this literary classic, we will uncover the origins that fueled Morrison’s vision, trace the contours of the story that unfolds at 124 Bluestone Road, and intimately meet the complex figures who populate this haunted landscape. Their struggles with memory, love, loss, and the very definition of humanity lay the groundwork for a narrative that is as challenging as it is profoundly moving, inviting readers to confront the unspeakable and to seek understanding in the depths of human experience.

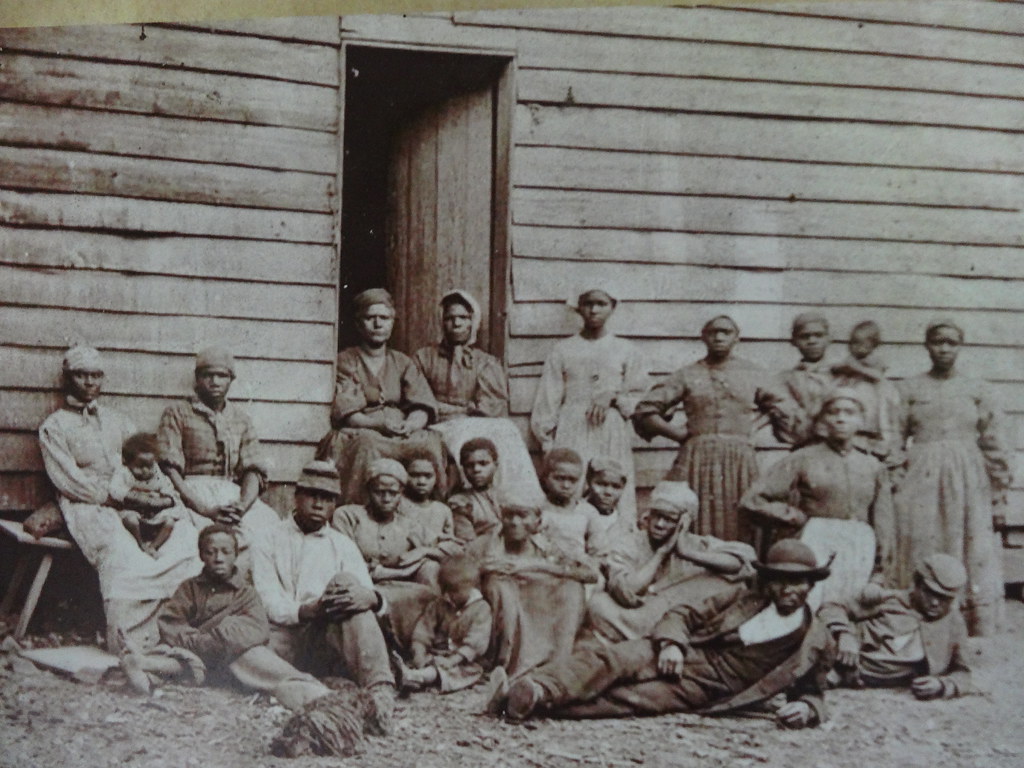

1. **The Genesis of a Masterpiece: Margaret Garner’s Story and Morrison’s Dedication**Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” is not merely a work of fiction; it is a profound literary response to a real-life atrocity, firmly rooted in the historical narrative of American slavery. The primary inspiration for the novel stems from the harrowing account of Margaret Garner, a slave from Kentucky who, in 1856, made a desperate bid for freedom by fleeing to the free state of Ohio. Her story, a stark illustration of the brutal realities enforced by the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, provides the agonizing historical backbone for Sethe’s own tragic choices within the novel.

Garner’s attempt to escape the horrors of re-enslavement culminated in an act of unfathomable desperation. When U.S. marshals cornered her and her children in a cabin, she attempted to kill them all, succeeding in taking the life of her youngest daughter, in the hopes of sparing them from a return to bondage. This chilling event was documented in an 1856 newspaper article titled “A Visit to the Slave Mother who Killed Her Child,” which Morrison encountered and reproduced in “The Black Book,” an anthology of Black history and culture she had edited in 1974. It was this historical fragment, this stark testament to a mother’s ultimate sacrifice against an inhumane system, that catalyzed Morrison’s creative process.

Beyond this specific incident, Morrison’s broader intention for “Beloved” is underscored by its poignant dedication: “Sixty Million and more.” This powerful phrase refers to the untold number of Africans and their descendants who perished as a direct consequence of the Atlantic slave trade. This dedication transforms the novel from a singular narrative into a universal memorial, a literary monument for those whose lives were brutally stolen or irrevocably scarred. Morrison herself articulated this very need, stating that “the book had to” exist as that memorial in the absence of suitable physical monuments. This deep sense of historical responsibility and commemoration permeates every page of “Beloved,” making it an essential act of remembrance and reckoning.

2. **The Haunting at 124 Bluestone Road: A Summary of the Narrative**The narrative of “Beloved” commences in 1873, in Cincinnati, Ohio, at the dilapidated house numbered 124 Bluestone Road, a place thoroughly steeped in a malevolent spiritual presence. Here lives Sethe, a formerly enslaved woman, with her 18-year-old daughter, Denver. The house has been haunted for years by what they believe is the ghost of Sethe’s eldest daughter, a presence so potent that it drove Sethe’s sons, Howard and Buglar, away by the age of 13. This opening immediately establishes an atmosphere of isolation, trauma, and the inescapable past.

The fragile existence at 124 is disrupted by the arrival of Paul D, an enslaved man from Sethe’s past at the Sweet Home plantation. His presence is a catalyst, challenging the established order of the haunted house by forcing out the malevolent spirit. Paul D attempts to rekindle a sense of normalcy and hope, persuading Sethe and Denver to leave the house for the first time in years to attend a carnival. However, upon their return, a young woman identifying herself as Beloved is found sitting on their doorstep, soaking wet and profoundly mysterious.

Beloved’s sudden appearance sets off a series of escalating psychological and emotional disturbances within the household. While Paul D harbors suspicion, Sethe is captivated, and Denver, starved for companionship, eagerly embraces Beloved, convinced she is her resurrected older sister. Beloved’s presence forces repressed memories to the surface for all characters, particularly Paul D, who endures horrific flashbacks of sexual violence and chain gang life after an encounter with her. The mystery deepens as Stamp Paid reveals a newspaper clipping detailing Sethe’s infanticide, unraveling the community’s long-standing ostracization of her and finally exposing the profound trauma that binds the family to their haunted home.

3. **Sethe: The Protagonist’s Burden of Memory and Maternal Love**Sethe, the undeniable protagonist of “Beloved,” is a woman defined by her harrowing past as an enslaved person and her fiercely protective, yet ultimately destructive, maternal love. Having escaped the brutal Sweet Home plantation, she carries the indelible marks of her bondage, including severe scars on her back that she ironically attempts to “beautify” by repeating a white girl’s description of them as a “Choke-cherry tree,” a perception that Paul D and Baby Suggs vehemently reject. Her resilience is evident, but it is inextricably interwoven with the trauma she endured, making her a figure constantly battling the internal and external manifestations of slavery.

Her life at 124 Bluestone Road is a testament to her repression of this trauma. The haunting, believed to be her murdered infant daughter, underscores her inability to escape the past. Sethe’s desperate act of infanticide—killing her eldest daughter and attempting to kill her other children—was, in her mind, an ultimate act of protection, an attempt to put her “babies where they would be safe” from the unimaginable horrors of re-enslavement under the vicious Schoolteacher. This decision, while abhorrent to the community, is rooted in her conviction that death was preferable to the “venomous anguish of life as an enslaved person,” revealing a profound, if distorted, moral framework shaped by her experiences.

As the narrative progresses, Sethe becomes convinced that the mysterious young woman, Beloved, is indeed the daughter she killed, a belief fueled by the fact that “BELOVED” was the only word she could afford to have engraved on the child’s tombstone. This conviction leads her to an obsessive devotion, spending all her time and money on Beloved, seeking to atone for her past actions. However, Beloved’s presence becomes parasitic, consuming Sethe’s life force, physically diminishing her while Beloved herself grows in size. This destructive dynamic highlights how Sethe’s unresolved guilt and singular focus on her past prevent her from truly living, embodying the novel’s exploration of trauma’s lingering grip and the arduous path to individual healing.

4. **Beloved: The Enigmatic Manifestation of Past Trauma**The character of Beloved is perhaps the most enigmatic and central figure in the novel, functioning as both a literal presence and a symbolic embodiment of the collective trauma of slavery. Her mysterious arrival, soaking wet from a body of water and appearing on the doorstep of 124 Bluestone Road, marks a turning point in the narrative. While widely believed to be the ghost of Sethe’s murdered baby—a belief reinforced by the cessation of the house’s haunting upon her arrival and her childlike behaviors—her true nature remains debated among scholars, some arguing for a more complex interpretation of mistaken identity, where she is a young woman escaped from another form of bondage who believes Sethe to be her mother.

Morrison herself clarified that Beloved is indeed the daughter Sethe killed, thereby solidifying her role as a direct manifestation of Sethe’s unbearable past. The name itself, derived from the single word Sethe could afford for her child’s tombstone, underscores her identity as the lost, unmourned, and deeply felt presence of a child brutally taken. Beloved acts as a catalyst, forcing Sethe, Paul D, and Denver to confront their repressed memories and the psychological wounds inflicted by slavery, serving as a conduit through which the unspeakable past finally finds a voice, leading to a potential reintegration of their fragmented selves.

However, Beloved’s influence is not solely restorative; it is also profoundly destructive. As Sethe dedicates herself entirely to appeasing Beloved, out of guilt and a desperate hope for family reunification, Beloved becomes increasingly demanding and volatile. She consumes Sethe’s resources and energy, growing physically while Sethe wastes away, symbolizing how an unresolved past, when clung to obsessively, can drain the life out of the present. Her spectral and demanding presence illustrates the “heavy ghost” of history, a force that, while demanding acknowledgment, can also become a suffocating burden, ultimately requiring exorcism for the living to move forward.

5. **Paul D: Reclaiming Manhood Amidst the Scars of Slavery**Paul D, one of the enslaved men from Sweet Home, arrives at 124 Bluestone Road bearing the deep, physical, and psychological scars of his past, representing the profound challenge to manhood under the institution of slavery. He carries with him not only memories of his time at Sweet Home but also the trauma of being forced into a chain gang, experiences that have made him perpetually transient and guarded. His heart is metaphorically described as a “tobacco tin,” a container in which he represses his painful memories, symbolizing the profound emotional suppression required for survival under brutal conditions.

His re-encounter with Sethe, a woman from his shared past, sparks a romantic relationship and a tentative hope for a new beginning. However, Beloved’s arrival intensely challenges his fragile equilibrium. She specifically targets his repressed trauma, cornering him and triggering horrific flashbacks of sexual violence and the dehumanizing conditions of his past, causing his “tobacco tin” heart to burst open. This confrontation forces Paul D to face the unspeakable, highlighting how slavery distorted and stripped enslaved men of their inherent masculinity, replacing it with a sense of animality and profound shame, particularly concerning his “neck jewelry”—the iron bit he was forced to wear.

Despite these immense challenges, Paul D demonstrates a crucial journey toward reclaiming his manhood. His initial suspicion of Beloved, his attempt to shield Sethe, and his eventual confrontation with Sethe over her infanticide, all point to his struggle to define himself on his own terms, beyond the confines of his past. By the novel’s end, he returns to a devastated Sethe, offering her comfort and a path toward self-love, telling her that she is her own “best thing.” This act of affirmation, alongside his own gradual healing, underscores Morrison’s exploration of how Black men, despite systemic oppression, endeavored to establish their identity and dignity in a society that sought to deny it.

6. **Denver: From Childhood Isolation to Communal Engagement**Denver, Sethe’s 18-year-old daughter, begins the novel as a shy, friendless, and housebound character, a direct consequence of her family’s isolation stemming from Sethe’s traumatic past and the haunting of 124 Bluestone Road. Her childhood has been shaped by the presence of the ghost of her elder sister, which she cherishes as her only companion, and the subsequent departure of her brothers, who fled due to their fear of Sethe and the unsettling supernatural presence. This profound isolation has stunted her development, keeping her in a state of prolonged childhood.

Beloved’s arrival, however, acts as an unexpected catalyst for Denver’s transformation. Initially, Denver clings to Beloved, eager to care for her and convinced she is her resurrected sister, an act that initially deepens her isolation within the household. Yet, as Beloved’s presence becomes increasingly demanding and parasitic, consuming Sethe’s life force and transforming Sethe into a childlike figure, Denver is forced to confront the harsh reality of their situation. She observes the destructive merger of Sethe and Beloved’s voices, realizing the peril her mother is in and recognizing the need for external intervention.

This realization marks Denver’s pivotal shift from a dependent child to a protective woman, initiating her journey towards individuation. Overcoming her deep-seated fear of the outside world and the community that had ostracized them, Denver courageously leaves the confines of 124 to seek help. Her act of reaching out to the Black community, asking Mr. Bodwin for work and inspiring the local women to intervene, is a monumental step towards breaking the cycle of isolation. By the novel’s end, Denver not only secures her personal independence but also plays a crucial role in her mother’s wellbeing, transforming into a working member of the community and embodying a new definition of heroism centered on communal care and self-determination.

7. **Baby Suggs: The Voice of Self-Love and Its Tragic Silencing**Baby Suggs, Sethe’s mother-in-law and Halle’s mother, stands as a figure of immense spiritual authority and communal leadership, particularly in the immediate aftermath of her freedom. Her son Halle worked tirelessly to buy her freedom, a rare and profound act that allowed her to travel to Cincinnati and establish herself as a respected leader. She became known for her powerful sermons in the Clearing, where she exhorted the Black community to love themselves—their bodies, their hearts, their hands, their eyes—because, as she recognized, “other people will not.” This message of radical self-affirmation was a vital balm for a community scarred by the systemic dehumanization of slavery.

However, Baby Suggs’s influence and the relative privilege she enjoyed through Halle’s actions eventually turned sour. Her generosity, epitomized by turning a simple meal into a lavish feast, ironically bred envy within the community, contributing to the family’s later isolation. More devastatingly, Sethe’s act of infanticide, driven by the trauma Baby Suggs herself had experienced through losing many of her own children to slavery, further alienated the family. The community’s horror at Sethe’s deed compounded their existing resentments, leading to a profound withdrawal of support.

As we conclude this profound journey through Toni Morrison’s “Beloved,” it becomes clear that its resonance extends far beyond the pages of a single novel. It is a enduring testament to the human spirit’s capacity to both endure and transcend unimaginable suffering, a vital act of remembrance for lives shattered by slavery, and a call to confront the persistent echoes of history. The novel compels us to listen to the “sixty million and more,” offering not just a story, but a pathway to understanding, healing, and a deeper appreciation for the complex tapestry of the human condition.