The 1970s, a decade often pigeonholed by its cultural quirks like bell-bottoms and disco, was, in reality, a crucible for cinematic innovation, widely recognized as the most astonishing period in film history. This was unequivocally the “director’s era,” a golden age when filmmakers, armed with burgeoning knowledge from film schools and newfound artistic freedom, seized control of the narrative. They bravely ventured into territories previously deemed taboo, deploying frank language, explicit sexuality, and unflinching themes, transforming the silver screen into a canvas for raw, unadulterated art that profoundly reflected its turbulent times.

This generation of visionary artists, many of whom honed their skills in the fast-paced world of television, fundamentally reshaped the cinematic landscape. Dubbed the “movie brats,” they not only stormed Hollywood, dominating the decade with their distinctive voices and challenging the established order, but also laid crucial groundwork for both the future of blockbusters and the burgeoning independent film movement. Their impact was staggering, a rare constellation of gifted creators whose influence continues to resonate through subsequent decades, their works still vital and relevant even as they now stand as the venerable “old guard” of cinema.

From sprawling epics exploring power and corruption to intimate psychological thrillers and searing social commentaries, these directors transcended mere entertainment to craft cultural touchstones. Their films delved into the human condition with unparalleled depth and visual flair, becoming enduring masterpieces that continue to captivate. Here, we embark on a deep dive into the minds and filmographies of five such influential directors, whose audacious visions cemented their legacies and continue to “wow us” with their timeless brilliance, illustrating precisely how a single decade could forever alter the very course of cinematic art.

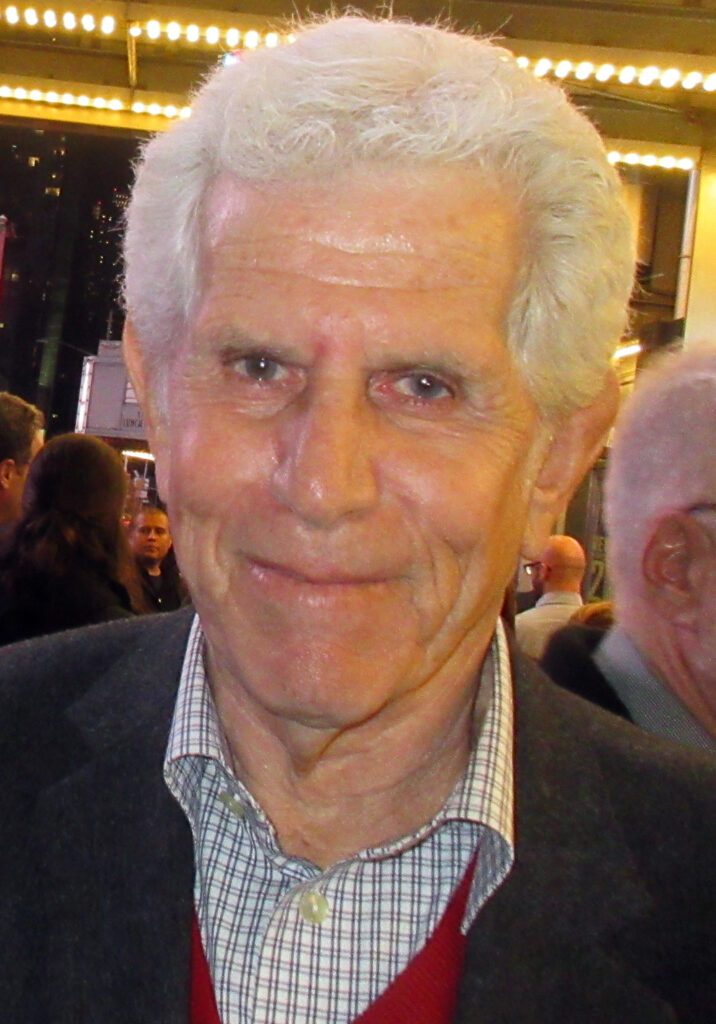

1. **Francis Ford Coppola: The Unrivaled Maestro of an Era** No director in film history dominated a decade with the sheer artistic force and consistency of Francis Ford Coppola in the 1970s. His run of masterpieces during this period is almost unimaginable. Upon being hired for ‘The Godfather,’ Coppola immediately perceived the novel as a profound, dark metaphor for the American Dream, meticulously exploring how immigrants seeking a better life sometimes found wealth through the shadowy avenues of crime. He brought the Corleone family’s ascent to power into vivid, unforgettable focus, utilizing Gordon Willis’s dark lighting to plunge audiences into the clandestine world of their operations, yet artfully presenting them as a loving family, whose ‘business’ simply happened to be crime.

Coppola’s genius extended even further with ‘The Godfather Part II,’ somehow surpassing the original. He imbued it with an epic sweep, exploring the Mafia’s overwhelming power and global reach with even greater depth. Seamlessly moving between Vito Corleone’s past as an immigrant and Michael’s present as a formidable chieftain, Coppola juxtaposed stunning images of hope at Ellis Island with the stark reality of corruption. The film’s masterful, often understated, editing facilitated a fluid movement between timelines, enriching the narrative and vividly illustrating how absolute power corrupts. This culminates in Michael’s tragic loss of his soul, a hauntingly intense portrayal by Al Pacino.

His unparalleled success culminated with ‘Apocalypse Now,’ a film he famously declared “is not about Vietnam, it is Vietnam,” capturing the war’s absolute madness and visceral beauty with breathtaking artistry. Loosely based on Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness,’ the film plunged viewers into a cinematic inferno, following Willard’s descent into the jungle to confront the rogue Colonel Kurtz. ‘Apocalypse Now’ boasts cinematography widely regarded as among the finest in film history, its surrealistic storytelling immersive and terrifying. Coppola’s pervasive presence never distracts from the experience, culminating an extraordinary decade that saw him earn two DGA Awards, five personal Academy Awards, and witness each of his directed films become Best Picture nominees, cementing his status as a cinematic deity.

2. **Robert Altman: The Genre-Bending Maverick** Robert Altman personifies the “director’s era” in the 1970s, consistently delivering surprises and challenging cinematic norms. He began the decade with a groundbreaking masterpiece, then followed with a prolific and idiosyncratic output that fundamentally altered what was permissible in comedy and revolutionized entire genres. Altman’s consistent brilliance is often compared to Renoir or Hitchcock, a testament to his sustained creative energy and artistic daring. His unique approach to storytelling and visual style marked him as a true innovator.

His 1970s odyssey began with ‘M*A*S*H’ (1970), arguably the most influential satire of all time, a war comedy bursting with endless comedic ingenuity that instantly established his unique voice. This was rapidly followed by ‘McCabe & Mrs. Miller’ (1971), a masterpiece-worthy revisionist Western that deconstructed the genre with melancholic, snow-laden beauty. Altman then explored new depths with ‘Images’ (1972), a thrilling psychological horror character study, showcasing an enigmatic and unsettling quality unlike any other Altman film. He continued this streak with ‘The Long Goodbye’ (1973), an almost-masterpiece neo-noir that brilliantly reprised the Philip Marlowe character, demonstrating his versatility and knack for reinventing classic tropes.

Altman’s creative zenith arrived with ‘Nashville’ (1975), a tour-de-force ensemble masterpiece. This film intricately wove together the lives of twenty-four characters, offering a sprawling, satirical portrait of America that remains iconic. Even when subsequent films like ‘Buffalo Bill and the Indians’ (1976) saw a slight dip in quality, Altman’s distinctive observant style—characterized by zooms, smart cuts, and an effortless flow—remained intact. He concluded his extraordinary run in 1977 with ‘3 Women,’ another enigmatic psychological thriller, further cementing his range and commitment to exploring human complexities. Altman was a consistent boundary-pusher, redefining cinematic “allowances” and leaving an indelible mark on genre filmmaking.

3. **Rainer Werner Fassbinder: The Prolific Auteur of the Human Condition** Rainer Werner Fassbinder was an extraordinary movie-making machine, whose brief yet incandescent career left an immense legacy on cinema. From his breakthrough with ‘The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant’ in 1972, he embarked on a relentless creative streak. He released at least one, and often two, great films every single year until his untimely death in 1982, before reaching 40 years old. In just approximately 13 years, he directed over 40 feature-length films, an output remarkable not only for its frequency but also for its consistent quality and ambitious thematic scope.

Fassbinder’s films are defined by their immense thematic complexity, offering incisive examinations of the human condition. He often explored societal pressures, power dynamics, and personal despair. Few of his films are without a touch of melancholy; many are deeply depressing, reflecting an unflinching look at the darker aspects of human existence. This commitment to challenging and often uncomfortable narratives made his work incredibly potent and emotionally resonant, establishing him as a master of psychological realism and social commentary, unafraid to expose difficult truths.

Beyond his thematic depth, Fassbinder’s visual style was distinct, layered, and instantly recognizable. He employed sophisticated depth of field, vibrant colors, neon lighting, and meticulously composed character arrangements, alongside precise blocking within the frame. These elements created striking cinematic worlds. This unique visual language, rich in textures and evocative palettes, positioned him as an eccentric yet brilliant bridge between Ozu’s minimalist aesthetics and Wes Anderson’s highly stylized compositions. His technical mastery and bold artistic choices ensured that each frame of a Fassbinder film was a carefully constructed piece of a larger, emotionally charged puzzle.

4. **Stanley Kubrick: The Formal Perfectionist’s Few, Unforgettable Films** Achieving a spot among the top five directors of a decade with only two feature films is an extraordinary feat, one accomplished solely by Stanley Kubrick. Both of his 1970s films secured a place within the top seven of the decade’s best, a testament to the unparalleled quality and profound impact of his work. Kubrick was a filmmaker whose meticulous attention to detail and unwavering artistic vision consistently resulted in films that were not just movies, but profound, unforgettable, and uncompromising experiences. His rare output was a guarantee of cinematic excellence, showcasing his singular genius.

His first 1970s contribution, ‘A Clockwork Orange’ (1971), is a startling drama set in a dystopian near-future. Decades later, it remains remarkably futuristic and disturbingly plausible. Based on Anthony Burgess’s novel, the film immediately pulls viewers into the bizarre world of Alex (Malcolm MacDowell), the gleefully violent leader of the droogs. Kubrick’s superb direction imbued Alex with a jaunty step and upbeat demeanor even amidst brutal acts. The fight sequences were staged with an almost balletic precision, rendering them both shocking and strangely beautiful. The film’s blackly comic tone, coupled with its unflinching portrayal of perversity and social conditioning, ensures that the camera’s relentless, in-your-face perspective offers an unforgettable glimpse into Alex’s twisted mind, leaving audiences both repulsed and utterly captivated.

Kubrick’s films are widely celebrated as formal, visual, and writing masterworks, and ‘A Clockwork Orange’ exemplifies this meticulous craftsmanship. Every element, from the production design to the unsettling soundtrack, was carefully orchestrated to create a cohesive and deeply unsettling experience. The film stands as an uncompromising vision, a unique work that only Kubrick could have successfully brought to the screen with such profound impact. His visionary approach ensured that even with a limited filmography in a decade dominated by prolific talents, his contributions stood as towering achievements, influencing countless filmmakers and sparking endless discussion.

5. **Andrei Tarkovsky: The Master of Slow Cinema and Visual Beauty** Andrei Tarkovsky’s esteemed position among the top directors of the 1970s is significantly amplified by his direction of what many critics consider the second-best film of the decade. While he did direct two other masterpieces during this period, they are often regarded as “lower tier” compared to the sheer, bombastic greatness of his seminal work, ‘Stalker.’ This single film alone tremendously elevates his standing, demonstrating a director in absolute control of his craft, who masterfully transformed slow cinema into a profound vehicle for philosophical inquiry and breathtaking visual artistry.

Tarkovsky was a filmmaker renowned for meticulously crafting every frame, known for his methodical, elegant approach to cinema. His works are characterized by rigorous formal detail and an overflowing visual beauty that frequently borders on the sublime. He possessed a unique ability to tackle exceptionally heavy, existential themes—exploring spirituality, memory, and humanity’s place in the universe—with a visual language both deeply personal and universally resonant. His long, contemplative takes and deliberate pacing invited audiences to fully immerse themselves in the cinematic experience, fostering a meditative engagement with his profound narratives.

The 1970s unequivocally marked Tarkovsky’s most artistically potent decade, solidifying his reputation as one of film history’s greatest auteurs. ‘Stalker,’ with its haunting atmosphere, deep philosophical underpinnings, and stunning cinematography, remains a perennial contender for the title of the best film ever made, a testament to his singular vision. His ability to evoke intense emotional and intellectual responses through his unique filmmaking style—where landscapes become characters and silence often speaks volumes—established him as an influential force, expanding the possibilities of cinematic expression and proving that patience in storytelling could yield unparalleled artistic rewards.

6. **Nicolas Roeg: The Visually Daring Innovator**Nicolas Roeg burst onto the cinematic scene in the 1970s with an undeniable force, seemingly emerging from “absolutely nowhere” to immediately establish himself as a director whose vision was as unique as it was unforgettably bold. His debut in the decade, “Memo for Turner,” was a “flabbergasting formal masterpiece” starring Mick Jagger. It introduced the world to Roeg’s “loud, detailed, expressive and endlessly imaginative” editing style, instantly captivating critics with its vibrant energy and unconventional rhythm.

Roeg’s genius extended beyond editing; his “very unique visual design” and confident “color choices” imbued his films with a distinct aesthetic. Following his debut, he explored “Australian wild life” in a film that, while a “big step down” from his earlier work, still contained “visual and narrative gems.” Roeg consistently pushed boundaries, proving cinema could be intellectually stimulating and visually arresting.

His creative journey continued with a “depressive, long-lasting and psychologically-disturbed horror film driven by guilt,” which many consider his personal best work. This film stood out for its narrative and stylistic strength, even surpassing the imaginative flair of his 1970 debut, and featured “some of Donald Sutherland’s and Julie Christie’s career best work.” This unsettling masterpiece delved deep into human psyche, showcasing Roeg’s comfort with dark, complex themes.

“The Man Who Fell to Earth” showcased Bowie’s “one-of-a-kind, brilliant performance” and pushed visual storytelling boundaries. Roeg’s direction was astonishing, with “powerful and the most imaginative” visuals and editing. From the initial “shots and editing choices,” audiences knew they were in for “one hell of a ride,” a profound and spectacular journey that solidified Roeg’s reputation.

7. **Roman Polanski: The Master of Psychological Depth and Atmospheric Thrills**Roman Polanski, a director of unparalleled vision, delivered “three masterpieces” in the 1970s, each a “completely different film,” yet unified by his “one central visionary force.” His work during this prolific decade cemented his reputation as a master craftsman, capable of crafting narratives that were deeply unsettling, visually meticulous, and profoundly impactful.

His most celebrated achievement is “Chinatown,” “the best work of his career.” While Robert Towne’s “exceptional screenplay” is praised, Polanski’s “old fashioned atmosphere,” “carefully constructed visual design,” and “imaginative presentation” “rest almost entirely on Polanski’s shoulders.” The iconic “final elevation of the camera” subtly emphasizes themes of corruption and fate.

Polanski then explored disturbing territory with “The Tenant,” a “disturbing, darkly funny and formally layered thriller.” “Anybody else could create such a powerful masterpiece out of such bizarre premise” is doubtful, showcasing Polanski’s talent. His knack for exploring trapped characters made this film unforgettable and unsettling.

He concluded the decade in spectacular fashion with “Tess,” a film that “looks like no other Polanski film to date.” This visually breathtaking adaptation was “truly painterly gorgeous,” with many speculating that its beauty was partly due to the cinematographer. Yet, it was Polanski who “directed every scene and every set-piece with such precision and detail like only he could,” ensuring every frame was a meticulously composed work of art, a stunning capstone to an incredibly influential decade for the director.

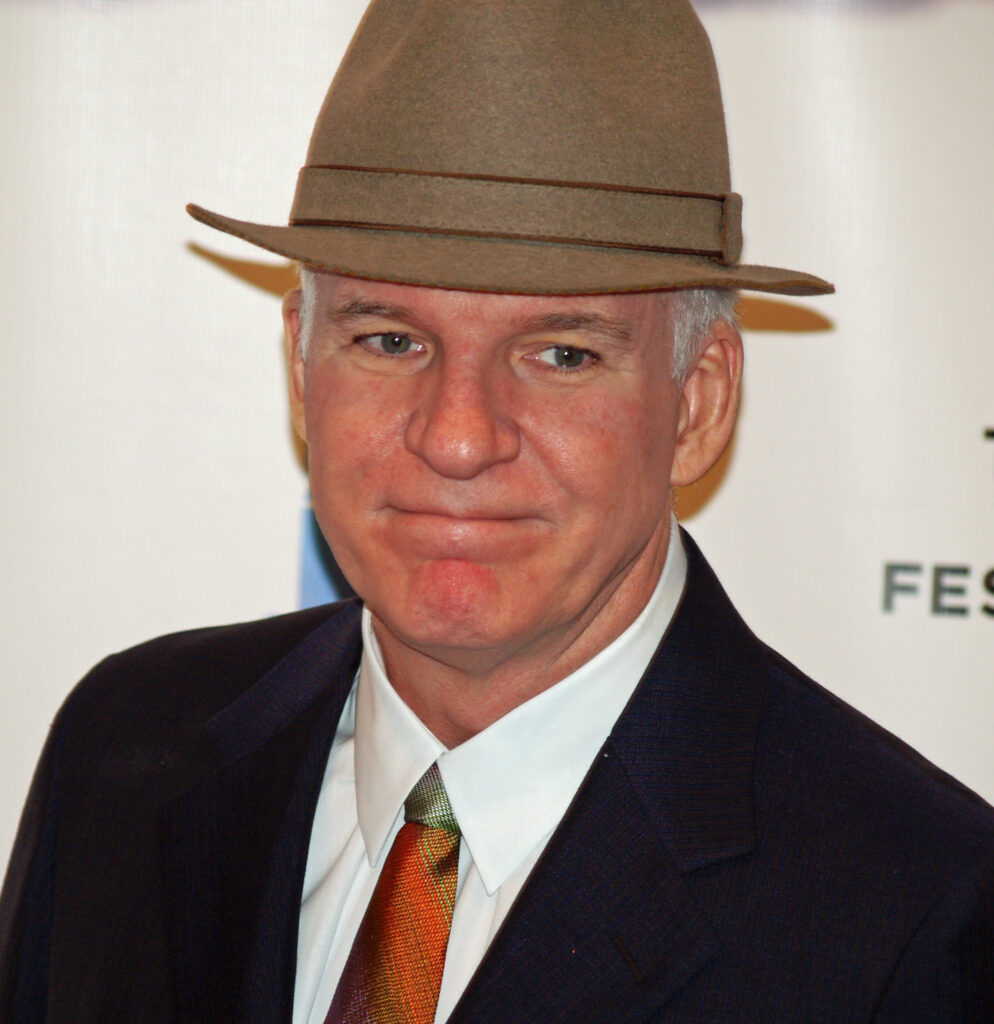

8. **Woody Allen: The Evolution of an Intellectual Comedian**Woody Allen’s 1970s journey began with an “uninteresting start,” “a lot of funny comedies with zero artistic flourish.” This quickly transformed, as Allen evolved from a comedic writer into a profound and inventive filmmaker. His career took off, demonstrating rapid growth in thematic depth and stylistic ambition.

The “legend of Woody” properly began with “Sleeper,” where he “proves as one of the funniest screenwriters of all time.” This talent was further “cemented with Love and Death,” establishing Allen “as also one of the most intelligent, imaginative and elegantly witty writers in any medium.” These early works refined his comedic timing, laying groundwork for later complex narratives.

“Annie Hall” saw Allen “climb up this list,” and it’s “easy to see why.” He maintained “imaginative comedy,” elevating it “to eleven,” and integrated “tender, believable and compassionate romance.” “Annie Hall” was groundbreaking for its “formal pops of genius in style of Godard,” incorporating “subtitles,” “animation cutaways,” and “split screens,” alongside a “sublime Antonioni style ending” and a “tour-de-force performance from Diane Keaton.”

Allen explored new depths with “Interiors,” a bold departure, which with Gordon Willis, “updated the visual beauty of Annie Hall and its thematic complexity.” His “first ‘serious’ film,” it “sucked out most of the humor,” leaving “dry, witty, and smart comedy woven with troublesome family dynamics.” He peaked with “Manhattan,” a “gorgeous film,” “his most visually impressive work, ever,” and arguably “Willis’s best work.” This masterpiece blended humor with “potent and delicately handled romance,” creating “the single best dramedy of all time and simply one of the best romance films ever made,” with “superb performances by Hemingway and Keaton” and “one of the strongest formal bookends” in its iconic “still life montage of NYC and Rhapsody in Blue.”

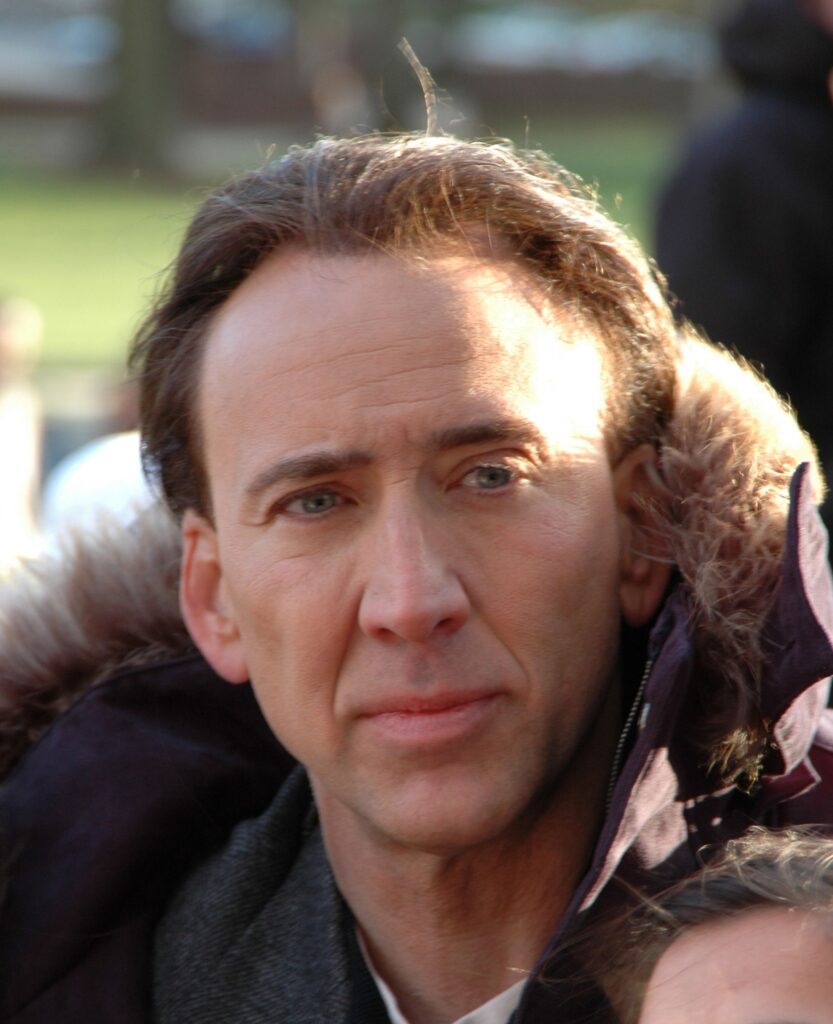

9. **Martin Scorsese: The Raw Poet of Urban Grit**Martin Scorsese burst onto the American cinematic scene in the 1970s with a raw, visceral energy, announcing “one of the most unique new voices.” His arrival was a stylistic bomb, marking him as “violent, cool, stylistically brave and weirdly funny,” and “new, exciting and completely unique.” His early work set the stage for a career defined by unflinching urban portraits, complex characters, and groundbreaking visual storytelling.

His breakout masterpiece, “Mean Streets,” firmly established his signature style, a distinct blend of gritty realism and kinetic filmmaking. After his explosive debut, Scorsese took a surprising turn with “Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore,” a “low key studio drama.” Though he handled this “standard material surprisingly well,” the film was “quite underwhelming and very stylistically dry,” with the context suggesting “anybody else” could have directed it to “similar results.” This detour underscored his personal, intense projects’ distinctiveness.

A “superb return to form” came with “Taxi Driver,” an undisputed classic and definitive statement on urban alienation. It was “gloomy and dark, thematically and stylistically layered, complex in its narrative and gorgeous in its expressive visuals.” Scorsese was “extremely successful in creating a haunting and magnetic atmosphere,” perfectly complementing Paul Schrader’s “all timer screenplay” and perhaps “the best work of De Niro’s career.”

“Taxi Driver” follows Travis (Robert De Niro), a Vietnam veteran driven to despair by the city’s “filth.” His encounter with “twelve-year-old hooker, Iris (Jodie Foster)” pushes him “over the edge.” His failed assassination leads to a brutal slaughter, ironically making him a “hero.” De Niro’s “seething performance” and Foster’s “remarkable” portrayal anchored the film’s brutal violence and “dream-like” nightlife. “New York, New York,” while “a bit underwhelming” after this, remained “very stylistically potent and a very Scorsese film,” still possessing its “funny and cool, yet kind of menacing” quality.

10. **Ingmar Bergman: The Enduring Scandinavian Philosopher**Ingmar Bergman, a titan of world cinema, was “one of the rare directors who appears in the top ten of three consecutive decades,” showcasing his sustained artistic brilliance. Though the 1980s and 90s were “pretty underwhelming” (except “Fanny and Alexander”), his 1970s output was remarkable, solidifying his legacy as an auteur whose work transcended entertainment for deep philosophical inquiries.

His 1970s contributions began with “Cries and Whispers,” praised as an “exploration of fiery family dynamics.” This “carnal, disturbing and hard to watch” masterpiece was elevated by its iconic “red set-design,” “perfectly amplif[ying] the conflicts and inner disturbances,” creating a visually arresting and emotionally charged experience. Its “detailed formal structure,” particularly “the fades to red,” represented “some of the most powerful formal work of Bergman’s career,” enhancing the “all time great writing by Bergman himself.”

Following this, “Scenes from a Marriage” delved even deeper into “world class writing,” showcasing Bergman’s masterful ability to craft compelling dialogue and intricate character studies. The film’s “dedication to the motifs of separation and togetherness” made it “one of the best things in any Bergman film,” and “one of his most uniquely directed films ever,” notable for its “surprisingly minimalist” approach.

Bergman rounded out the decade with “Autumn Sonata,” another “very standard Bergman film,” and by his high standards, “an almost masterpiece.” This film featured “simply incredible writing, performances, production design and formal bookends,” demonstrating his consistent mastery. Its themes were “simple, yet complex,” and its overall execution “all-around brilliant.” Bergman’s indelible mark on the 1970s reinforced his reputation as a director whose works, though often somber, were universally acclaimed for their profound psychological insights, formal elegance, and timeless exploration of existential questions.

**An end to an astonishing era… and an enduring legacy.**

As we conclude this journey, looking back at these ten extraordinary filmmakers, it’s clear why the 1970s stands as a beacon of cinematic innovation. This decade saw audacious visions flourish, with directors daring to challenge conventions and redefine film’s language. From Coppola’s epics to Bergman’s dramas, Altman’s satires to Scorsese’s urban poetry, each contributed a unique brushstroke to a vibrant, vital period. Their films were reflections of a turbulent era, mirrors to the human condition, crafted with unrivaled artistic integrity. Many of these “movie brats” and masters are still creating, influencing, and reminding us of that magical time when cinema became art. Their legacies live vibrantly on screen, continuing to “wow us” with timeless brilliance, proving true artistry never fades.