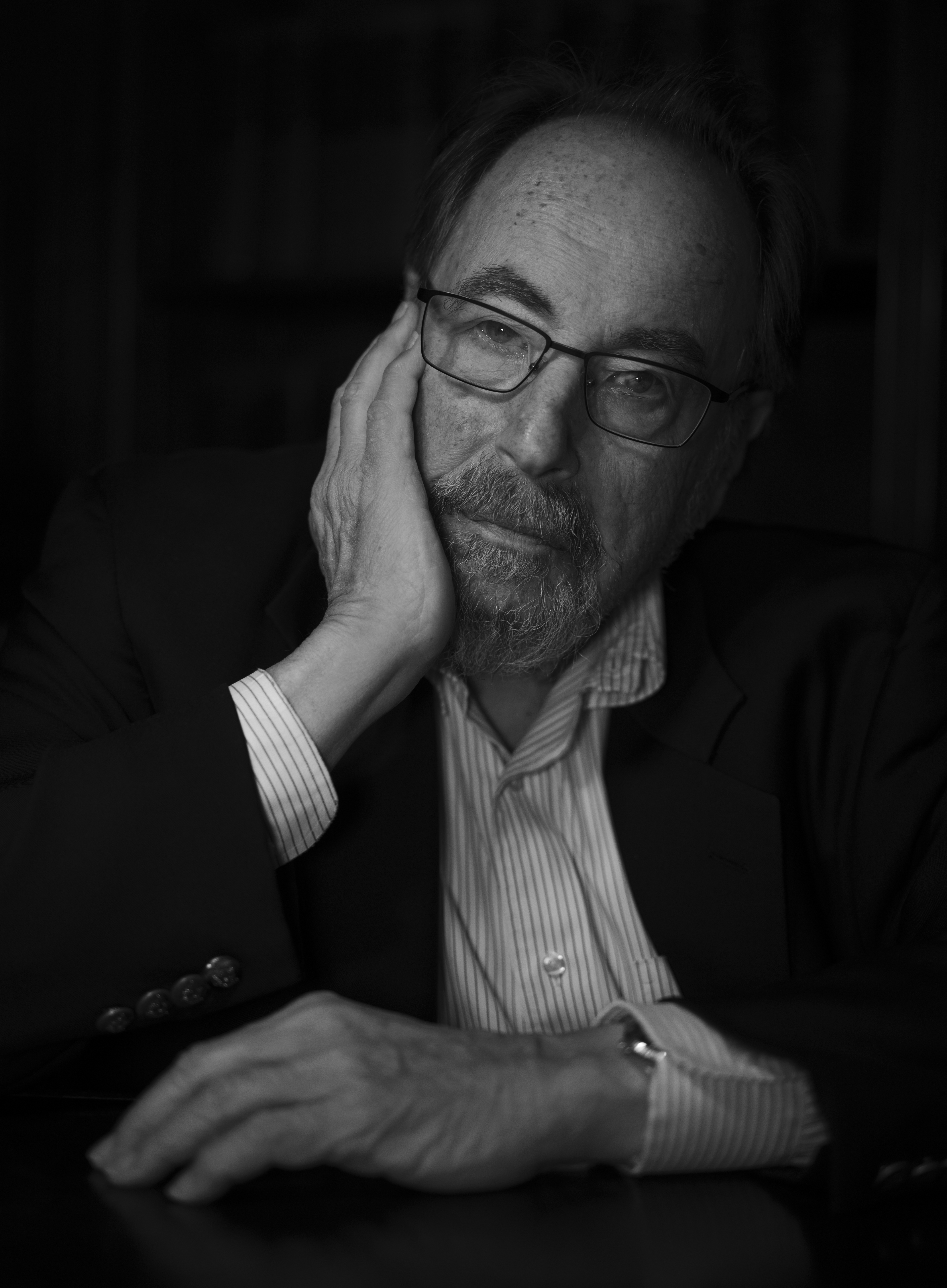

David Baltimore, a towering figure in modern biology whose groundbreaking discoveries reshaped our understanding of genetic information flow and profoundly influenced fields from immunology to cancer and AIDS research, died on Saturday at his home in Woods Hole, Mass. He was 87. The cause was complications of several cancers, his wife, Alice Huang, said. His passing marks the end of an extraordinary intellectual life, one characterized by unparalleled scientific acumen, bold leadership, and a steadfast commitment to advancing human health.

Dr. Baltimore, who shared the 1975 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine at the remarkably young age of 37, challenged what was then a foundational tenet of biology, the central dogma. His work did not merely add to existing knowledge; it reoriented the very trajectory of molecular biology, revealing a fluidity in genetic information transfer previously thought impossible. This revelation laid the groundwork for understanding retroviruses, including H.I.V., and paved the way for innovative gene therapies now used to correct genetic diseases.

Throughout a career that spanned more than half a century, Dr. Baltimore remained at the forefront of scientific inquiry, admired and envied in equal measure. He navigated intense scientific and political scrutiny, led two prominent universities, and served as an early, fervent proponent of AIDS research. This article will explore the pivotal moments and profound contributions that defined the life and enduring legacy of David Baltimore.

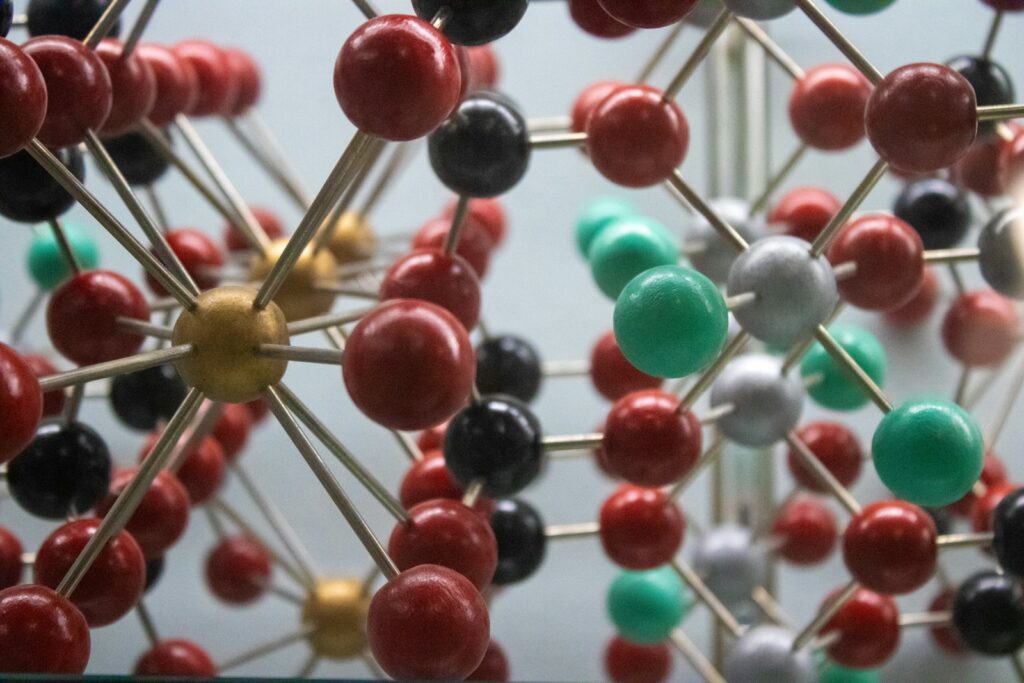

1. **The Nobel-Winning Discovery of Reverse Transcriptase**In 1970, while at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, David Baltimore made the startling discovery that would earn him a share of the Nobel Prize five years later. His work revealed that retroviruses, a class of RNA viruses, possess a unique enzyme capable of generating a DNA copy from viral RNA. This enzyme, which he named reverse transcriptase, was so named because it reversed the then-assumed direction of genetic information flow within cells.

This finding was not merely incremental; it was a fundamental shift in scientific understanding. As Carlos Lois, a neuroscientist and Baltimore’s colleague at Caltech, eloquently stated, “The experiment is an exemplar of excellence and simplicity.” Lois further noted the remarkable context of this achievement: “It is a testament to David’s acumen that he had never worked with retroviruses before! For this experiment, he requested purified retroviral particles from another lab at the National Institutes of Health. The viruses were sent to him by mail, and he did the experiment. So, the first time that he had ever worked with retroviruses, he did an experiment that got him a Nobel Prize.”

The existence of reverse transcriptase provided a crucial molecular mechanism for understanding how certain viruses operate and propagate. This enzyme became indispensable for subsequent research, enabling laboratories worldwide to study the molecular biology of retroviruses. Its discovery was a direct catalyst for the biotechnology revolution of the early 1980s, as the application of reverse transcriptase became central to cloning and manipulating genes, technologies that underpin much of modern molecular biology and genetic engineering.

2. **Upending the Central Dogma of Molecular Biology**Prior to Dr. Baltimore’s discovery, the prevailing belief in molecular biology was encapsulated in what was known as the central dogma. This dogma dictated that genetic information flowed in a singular, unidirectional manner: from DNA to RNA, and then to the synthesis of proteins. This principle had been a cornerstone of the fledgling field, providing a seemingly immutable framework for cellular processes.

Dr. Baltimore’s identification of reverse transcriptase directly challenged this established tenet. By demonstrating that information could also flow in the reverse direction, from RNA to DNA, he effectively “rocked the foundations” of the field. This revelation was profound, indicating a flexibility in genetic information transfer that scientists had not previously contemplated. It expanded the conceptual landscape of molecular biology, forcing a re-evaluation of fundamental assumptions about life’s molecular machinery.

The impact of this discovery was immediately recognized by his peers. David Botstein, a former Princeton professor and a friend of Dr. Baltimore during their time at MIT, recalled the moment Dr. Baltimore first presented his data. “I remember it like it was yesterday,” Dr. Botstein said, recounting an evening seminar in an M.I.T. classroom. “He gave this talk and I remember walking out of it and saying to Maurie Fox” — another faculty member — “‘He is going to get the Nobel Prize for that.’” Botstein’s prescient prediction materialized just a few years later.

In 1975, Dr. Baltimore was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine, sharing the honor with Howard Temin, who had independently made the same discovery, and Renato Dulbecco, for his significant work on tumor viruses. The Nobel committee recognized their collective contributions “for their discoveries concerning the interaction between tumor viruses and the genetic material of the cell,” highlighting the immense significance of reverse transcriptase in understanding viral mechanisms and their links to disease.

3. **Early Life, Education, and Academic Beginnings**David Baltimore was born on March 7, 1938, in Manhattan to Richard and Gertrude (Lipschitz) Baltimore. His formative years included a significant move to Great Neck, N.Y., on Long Island, when he was in second grade. This relocation was orchestrated by his parents, who sought to ensure that David and his younger brother, Robert, could attend better schools, underscoring an early emphasis on education within the family.

While his father worked in the garment industry selling women’s clothes and never attended college, his mother pursued higher education, studying psychology at the New School and later becoming a tenured faculty member at Sarah Lawrence at age 62. This blend of practical background and academic pursuit within his family environment likely contributed to David’s own unique intellectual path, fostering both an appreciation for real-world application and rigorous scholarly inquiry.

From a young age, David exhibited exceptional academic prowess, displaying a brilliance that bordered on the precocious. He was, by his own admission, “perhaps a bit of a show-off.” During high school, he famously turned in only the answers for his math homework, written in the upper corners of pieces of paper, because he could solve everything mentally. “I simply wrote down all the answers, without having to do any calculations,” he recounted in an oral history interview for the California Institute of Technology. “It all came very easily to me.” This early display of intellectual self-assurance would characterize his scientific career.

His passion for science crystallized after his junior year in high school, during a summer spent at the Jackson Laboratory in Maine, a renowned center for mouse genetics studies. “I made the discovery that a person with only the education I have could work at the forefront of science,” Dr. Baltimore reflected. This transformative experience cemented his life’s direction: “I came back and said, ‘This is what my life is going to be.’” This clarity of purpose propelled him forward, setting the stage for his future scientific endeavors.

Read more about: Jay North, the Enduring Spirit of ‘Dennis the Menace’ Star, Dies at 73: A Comprehensive Look at His Tumultuous Journey and Lasting Impact

4. **Foundational Research at Rockefeller and Salk Institutes**Upon completing high school, David Baltimore had his choice of colleges, ultimately selecting Swarthmore, where he truly discovered his vocation. His time there coincided with the nascent stages of molecular biology, a field that was rapidly taking shape and promised revolutionary insights into life itself. “I realized I was living through a revolution that I could become part of,” he said in an interview, captivated by the unfolding discoveries of the genetic code and how genes instruct protein synthesis.

His academic journey continued at Rockefeller University in New York City, where he joined the Ph.D. program, initially focusing on bacteriophages before a summer course on animal virology at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory shifted his focus. He transferred to work with Richard Franklin, a pioneer in the molecular biology of animal viruses, and rapidly made his mark. His work, focusing on the replication of RNA viruses like poliovirus, attracted immediate attention, leading to a Ph.D. in only two years.

Dr. Baltimore’s Ph.D. thesis in 1964 was regarded as a major breakthrough, establishing crucial methods for studying viruses in animal cells. Its significance was underscored during his thesis defense when Igor Tamm, a professor of virology and medicine, lauded Dr. Baltimore’s work as one of those rare instances “in the development of a field of knowledge when the ground for the next major development is laid.” This early recognition foreshadowed the profound impact his subsequent research would have.

A year after earning his doctorate, Dr. Baltimore was enticed by Renato Dulbecco to join the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego. It was at the Salk Institute that he met Alice Huang, an accomplished biologist who had just arrived as a postdoctoral fellow after receiving her Ph.D. at Johns Hopkins. Their scientific partnership blossomed into a personal one, and they married three years later, forging a powerful intellectual and personal bond that would last 57 years.

5. **The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Years and Initial Breakthroughs**In 1968, David Baltimore joined the faculty of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a move that would prove to be immensely consequential for his career and for the field of molecular biology. It was within two years of his arrival at MIT that he embarked on the pivotal work that would culminate in his Nobel Prize, making his seminal discovery of reverse transcriptase.

The MIT biology department during this era was a vibrant, highly competitive environment, famously populated by a group of what were described as “Young Turks.” Dr. Baltimore was undoubtedly among them, known for his “competitive smartness.” His presence attracted a coterie of graduate student aspirants who “hung onto his every word and vied to work in his lab,” drawn to his intellect and the exciting research underway. His friend David Botstein noted, “Most of us young faculty at M.I.T. were thought of as arrogant. David fit into that culture of competitive smartness. He was the smartest of all.”

The informal setting of an evening seminar in an MIT classroom, room 16-310, became the stage for Dr. Baltimore’s first presentation of the data that would overthrow the central dogma. He invited only faculty and friends, creating an intimate yet highly charged atmosphere for this groundbreaking revelation. Dr. Botstein, who was present, vividly recalled the moment: “I remember it like it was yesterday… He gave this talk and I remember walking out of it and saying to Maurie Fox… ‘He is going to get the Nobel Prize for that.’”

A few years later, Botstein’s prediction came true. The news of his Nobel Prize reached him in a uniquely personal way. Dr. Alice Huang, his wife and an accomplished biologist who was working alongside him in his lab during the prizewinning discovery, was attending a conference in Copenhagen in 1975 when she learned the news from a committee member. She “immediately got on the phone and called me,” Dr. Baltimore recalled in an interview for his obituary, speculating that he was probably “the only person who ever was told he had won a Nobel Prize by his wife.” This personal anecdote highlights the shared journey and profound connection between the two scientists.

6. **The Genesis and Founding of the Whitehead Institute**Following his groundbreaking discovery and Nobel recognition, David Baltimore’s influence extended beyond his laboratory, into the realm of institutional leadership and scientific infrastructure. In 1982, he co-founded the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, a major research center for molecular biology and genetics, partnering with philanthropist Edwin C. “Jack” Whitehead. This initiative underscored his vision for fostering cutting-edge science in a collaborative environment.

Dr. Baltimore served as the founding director of the Whitehead Institute until 1990. Under his guidance, the institute rapidly ascended to prominence. Within a decade of its establishment, the Baltimore-led Whitehead Institute was recognized as the world’s top research institution in molecular biology and genetics, a testament to his strategic vision and leadership. This success was built on a foundation of attracting exceptional talent and cultivating an environment conducive to breakthrough discoveries.

Phillip Sharp, an MIT Institute Professor Emeritus and fellow Nobel laureate, remarked on Baltimore’s enduring impact: “Of all David’s myriad and significant contributions to science, his role in building the first independent biomedical research institute associated with MIT and guiding it to extraordinary success may well prove to have had the broadest and longest-term impact.” Ruth Lehmann, the current director and president of the Whitehead Institute, similarly acknowledged her indebtedness, stating, “I, like many others, owe my career to David Baltimore. He recruited me to Whitehead Institute and MIT in 1988 as a faculty member, taking a risk on an unproven, freshly-minted PhD graduate from Germany.”

A key aspect of the Whitehead Institute’s mission under Baltimore’s direction was the cultivation of the next generation of scientific leaders. To this end, he established the Whitehead Fellows program, an innovative initiative designed to provide exceptionally talented recent Ph.D. and M.D. graduates with the unparalleled opportunity to launch their own independent laboratories, bypassing traditional postdoctoral positions. David Page, MIT professor of biology and the Whitehead’s first fellow, lauded this strategy, noting that it reflected Baltimore’s “recipe for institutional success: gather up the resources to allow young scientists to realize their dreams, recruit with an eye toward potential for outsized impact, and quietly mentor and support without taking credit for others’ successes — all while treating junior colleagues as equals.”

7. **Pioneering AIDS Research and Global Health Advocacy**Even after his monumental Nobel-winning discovery, David Baltimore demonstrated remarkable intellectual agility and a profound commitment to addressing urgent global health challenges. In 1986, he redirected a significant portion of his laboratory’s focus to AIDS research, recognizing the escalating threat posed by the human immunodeficiency virus. He also took on a leadership role, heading a national committee on AIDS policy, signaling his dedication to not only scientific inquiry but also public health strategy.

Baltimore understood the gravity of the emerging AIDS pandemic and tirelessly advocated for broader scientific engagement. He pleaded with other virologists to turn their attention to the crisis, stating, “I said it is the responsibility of anyone working in virology to get involved in this problem. It threatens to be the worst public health disaster of our time.” Despite his impassioned pleas, he noted with regret that “most of the virology community did not respond. They were very involved in their own work and AIDS had gotten very politicized.” This observation highlights both his foresight and the challenges of mobilizing the scientific community against a complex, politicized health issue.

His commitment to understanding and combating HIV was unwavering. He continued to research HIV through the AIDS crisis until the very end of his research career. According to Vincent Racaniello, a virologist at Columbia University and a former postdoc in Baltimore’s lab, some of Dr. Baltimore’s final experiments were focused on working on gene therapies for those with HIV/AIDS. This sustained dedication underscores his profound sense of responsibility toward improving the human condition through scientific endeavor.

Earlier in his career, following the Nobel Prize, Baltimore had already reoriented his laboratory’s focus to pursue a mix of immunology and virology. This shift laid the groundwork for his later deep involvement in AIDS research, as it equipped his lab with the expertise necessary to tackle the complexities of a retrovirus that attacks the immune system. His foresight in diversifying his research interests proved crucial in his ability to respond effectively to new scientific and public health imperatives.

Read more about: Remembering Queer Icons: A Look Back at 9 Celebrities Who Lost Their Lives to AIDS

8. **The Baltimore Affair: A Decade of Controversy and Resilience**David Baltimore’s illustrious scientific career faced intense scrutiny during the “Baltimore affair” in the mid-1980s. This protracted controversy involved accusations of scientific fraud concerning a 1986 paper, co-authored by Baltimore and published in *Cell*, detailing immune system gene rearrangement. Notably, Dr. Baltimore himself was never accused of misconduct, and the work was not conducted in his lab.

The allegations originated from a postdoctoral fellow in the lab of his MIT colleague, Thereza Imanishi-Kari, who claimed an inability to replicate experiments. Dr. Baltimore staunchly defended his co-author, refusing retraction, a stance that ignited a decade-long saga involving the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Secret Service, and politically charged congressional hearings. This public spectacle profoundly impacted his professional life and reputation.

As the investigation escalated, including forensic analysis of lab notebooks, Dr. Baltimore’s leadership faced severe pressure. Having become president of Rockefeller University in 1989, his tenure was abruptly cut short. When a leaked NIH report in 1991 found Dr. Imanishi-Kari guilty, the public outcry forced Dr. Baltimore to resign from his presidency after just 18 months, a significant personal and professional setback.

Despite the intense toll, Baltimore’s resolve remained firm. He consistently insisted there had been no fraud, standing his ground against Representative John Dingell Jr. This unwavering defense was ultimately vindicated in 1996 when an appeals panel dismissed the claims. The ordeal concluded with Dr. Baltimore finding solace in a *New York Times* editorial that finally cleared his name, marking the end of a challenging chapter that tested his remarkable resilience.

9. **Steering the California Institute of Technology: A Return to Academic Leadership**Emerging from the shadow of the Baltimore affair, David Baltimore received a profound vote of confidence. In 1997, just a year after his exoneration, he was appointed president of the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), a prestigious institution renowned for its scientific and engineering prowess. This appointment marked a significant return to high-level academic leadership, reaffirming his standing as a towering figure in global science.

During his tenure at Caltech, which lasted until 2006, Dr. Baltimore continued to shape scientific research and education. He spearheaded various fundraising initiatives, particularly bolstering the biological sciences. He also established a three-million-dollar fund dedicated to supporting student-life activities and services, demonstrating a holistic approach to institutional development beyond pure research.

Beyond fundraising, Dr. Baltimore championed diversity and inclusion. He actively led policies to increase campus diversity and notably brought more women into administrative roles, fostering a more equitable and inclusive academic environment. His leadership at Caltech was characterized by a forward-thinking vision for institutional excellence and broad-based academic support.

Upon stepping down as president in 2006, Dr. Baltimore did not retire from scientific inquiry. Instead, he remained at Caltech as a professor of biology, returning to his laboratory to focus on research and teaching. This transition underscored his lifelong passion for direct scientific engagement, allowing him to continue exploring fundamental biological questions, including his sustained work on viral vectors and mammalian immune systems.

10. **Enduring Scientific Contributions: Immunology, Cancer, and Gene Therapies**David Baltimore’s Nobel Prize in 1975 was monumental, yet far from the end of his scientific contributions. Following this discovery, he demonstrated remarkable intellectual agility, reorienting his laboratory’s focus to delve into immunology and virology. This strategic shift laid the groundwork for a series of other significant breakthroughs, reshaping biological understanding with direct implications for human health.

One pivotal achievement was the identification of NFkappaB, a major regulator for inflammatory processes, now understood to be implicated in numerous autoimmune diseases and cancers. Concurrently, his students discovered genes responsible for antibody diversity, providing a molecular understanding of how the immune system generates billions of different antibodies. These discoveries proved crucial for targeted therapies and understanding immune responses.

A tangible outcome of his later work was its contribution to developing the cancer drug Gleevec. This groundbreaking medication, the first small molecule targeting an oncoprotein inside cells, emerged from investigations into how certain viruses cause cell transformation and cancer, including his discovery of a cancer-causing gene in the Abelson leukemia virus. This showcased his profound impact on clinical medicine, translating insights into life-saving treatments.

Even in his final research years, Dr. Baltimore remained committed to urgent health challenges. His former postdoc, Vincent Racaniello, noted that some of Dr. Baltimore’s final experiments focused on gene therapies for HIV/AIDS. This sustained dedication, extending decades beyond his initial Nobel recognition, exemplified his unwavering pursuit of scientific solutions to improve the human condition, continually pushing boundaries in medical science.

11. **Championing Bioethics and Responsible Scientific Innovation**Beyond his laboratory and academic institutions, David Baltimore emerged as a leading voice in critical discussions surrounding bioethics and responsible scientific advances. His foresight in addressing societal implications of new technologies was evident early in his career, shaping foundational principles for genetic research that still influence policy today.

In 1975, the year he received his Nobel Prize, Dr. Baltimore co-organized the landmark Asilomar Conference on Recombinant DNA Molecules. This pivotal gathering brought together scientists, lawyers, and ethicists to establish self-imposed guidelines for safe genetic technology. Asilomar became legendary for its foundational discussions, setting a crucial precedent for proactive ethical considerations in rapidly evolving scientific fields.

His commitment to defining ethical boundaries for biological advances continued. In 2015, Dr. Baltimore was among prominent scientists who publicly called for a global ban on using genome-editing techniques to alter human DNA. This advocacy underscored his deep concern for the long-term societal impacts of powerful new technologies and the necessity of international dialogue before profound biological interventions.

Current Caltech President Thomas F. Rosenbaum acknowledged this, noting Baltimore’s “deep involvement in international efforts to define ethical boundaries for biological advances.” Dr. Baltimore understood that scientific progress carries profound responsibilities. He tirelessly advocated for a thoughtful, cautious approach to ensure innovation served humanity’s best interests, leaving an enduring model for integrating science with social responsibility.

12. **A Profound Mentor and Cultivator of Scientific Talent**David Baltimore was celebrated not only for his monumental discoveries but also for his profound impact as a mentor to generations of aspiring scientists. He possessed a unique ability to inspire and empower, creating vibrant environments where young researchers could thrive. His mentorship style blended challenging intellect with genuine, unwavering support.

Ruth Lehmann, director of the Whitehead Institute, recalled how Baltimore’s mentorship shaped her career. “I, like many others, owe my career to David Baltimore,” she stated, remembering how he “recruited me to Whitehead Institute and MIT in 1988 as a faculty member, taking a risk on an unproven, freshly-minted PhD graduate.” She lauded his skill at “bringing together talented scientists” and facilitating collaboration.

The Whitehead Fellows program, which Dr. Baltimore founded, stands as a testament to his innovative mentorship. This program offered exceptionally talented recent Ph.D. and M.D. graduates the unparalleled opportunity to launch independent laboratories, bypassing traditional postdoctoral positions. David Page, the Whitehead’s first fellow, praised this “beautiful strategy,” reflecting Baltimore’s “recipe for institutional success” by empowering young scientists.

Vincent Racaniello, a former postdoc, initially felt “scared to death” to join a Nobel laureate’s group, yet found Baltimore “made me so comfortable.” This highlights Baltimore’s ability to foster a supportive atmosphere amidst rigor. His colleague, Carlos Lois, described Baltimore’s lab as “electrifying” and “tremendously inspiring,” noting the unparalleled motivation and drive among his team, a direct reflection of Baltimore’s nurturing leadership.

13. **A Multifaceted Life: Broad Interests Beyond the Laboratory**While David Baltimore’s public persona was defined by his unparalleled scientific achievements, those closest to him knew a man of remarkably diverse interests and a zest for life extending far beyond the lab. He was a polymath in spirit, engaging with the world with an insatiable curiosity that permeated every aspect of his existence.

Thomas Palfrey, an economist and close friend at Caltech, offered a personal glimpse into this rich inner life. “Everyone knows about [his science],” Palfrey said, “But what they probably don’t know is how diverse and broad his interests were: music, classical, jazz, art, wine, exceptional food.” This portrayal reveals a man who appreciated culture and gastronomy, suggesting a deep engagement with aesthetic and sensory pleasures.

Palfrey further elaborated on Baltimore’s relentless drive and enthusiasm. “He led a very multifaceted life, one of these people who put his foot on the accelerator and never let up his whole life,” he recalled. “The amount of things that he did—traveling for pleasure and work—were mind-boggling.” This speaks to an individual who embraced life fully, balancing rigorous academic pursuits with a passion for exploration and experience.

His commitment to his friends and the broader world was also a defining characteristic. “He cared about his friends, and he cared about the world,” Palfrey emphasized. “A lot of his work was trying to improve the human condition. He should be remembered for that.” This sentiment underscores that even his “outside” interests were connected to a larger humanitarian perspective, suggesting his scientific endeavors were part of a deeply integrated personal philosophy dedicated to global betterment.

14. **An Enduring Legacy: Reshaping the Landscape of Science and Medicine**David Baltimore’s passing at 87 marked the culmination of an extraordinary intellectual journey, leaving an indelible legacy that reshaped biology and profoundly influenced medicine. His contributions, spanning over half a century, extended far beyond the Nobel-winning discovery of reverse transcriptase, creating ripples felt across diverse scientific disciplines.

His pioneering work laid the foundation for understanding retroviruses, including HIV, and directly informed gene therapies now used to correct genetic diseases. The biotechnology revolution of the early 1980s was a direct consequence of applications derived from his seminal discoveries, underscoring his role as a catalyst for modern molecular biology and genetic engineering, fundamentally altering scientific methodology and therapeutic approaches.

Beyond his direct research, Dr. Baltimore’s impact as an institution builder was monumental, exemplified by his founding of the Whitehead Institute and his presidencies at Rockefeller University and Caltech. Through these roles, he cultivated environments of scientific excellence, fostered the next generation of researchers, and championed diversity in academia, leaving behind thriving institutions embodying his forward-thinking vision.

His commitment to ethical leadership was equally significant, demonstrated by his instrumental role in establishing bioethical guidelines at the Asilomar Conference and his later advocacy for responsible genome editing. He tirelessly worked to ensure innovation served humanity’s best interests, advocating for a human-centered approach to scientific advancement.

Read more about: Joshua Abram’s Enduring Legacy: How a Visionary Reshaped Workspace, Advertising, and Fertility Care

As the scientific community reflects on the life and work of David Baltimore, it is clear that his legacy is one of transformative impact. He was a scientist who dared to challenge established dogmas, a leader who shaped institutions and inspired countless individuals, and a visionary who consistently looked beyond immediate discovery to consider the broader ethical and societal implications of his work. His remarkable intellect, coupled with his deep commitment to human well-being, ensured that his name will forever be etched in the annals of science, a testament to a life lived at the forefront of discovery and dedicated to the relentless pursuit of knowledge for the betterment of humankind.