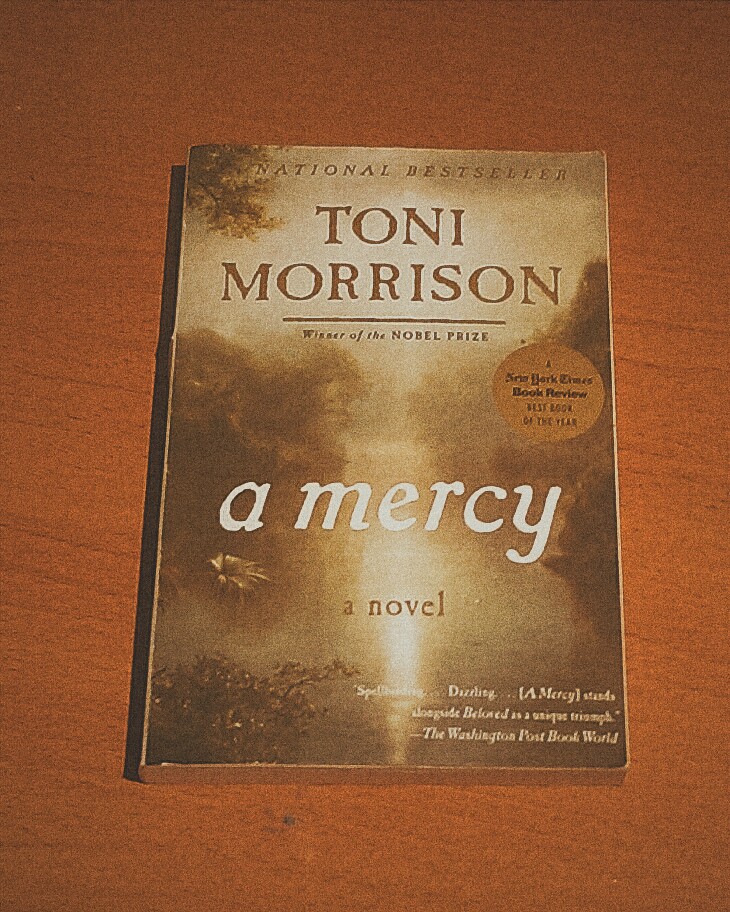

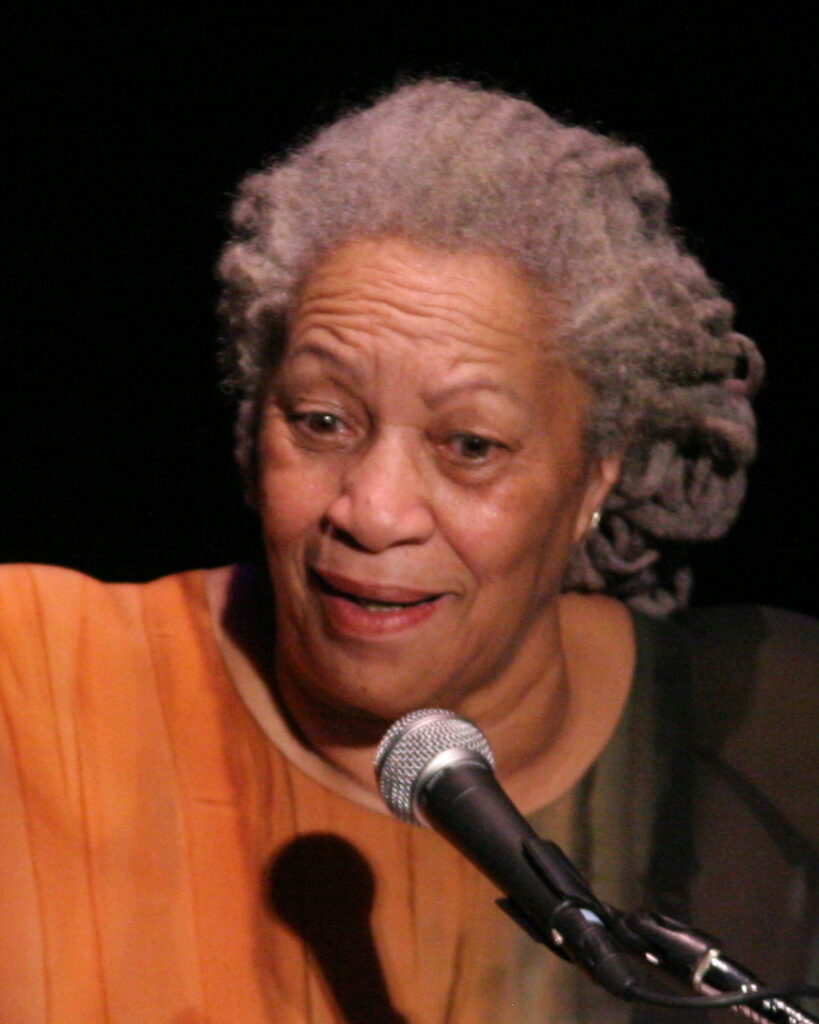

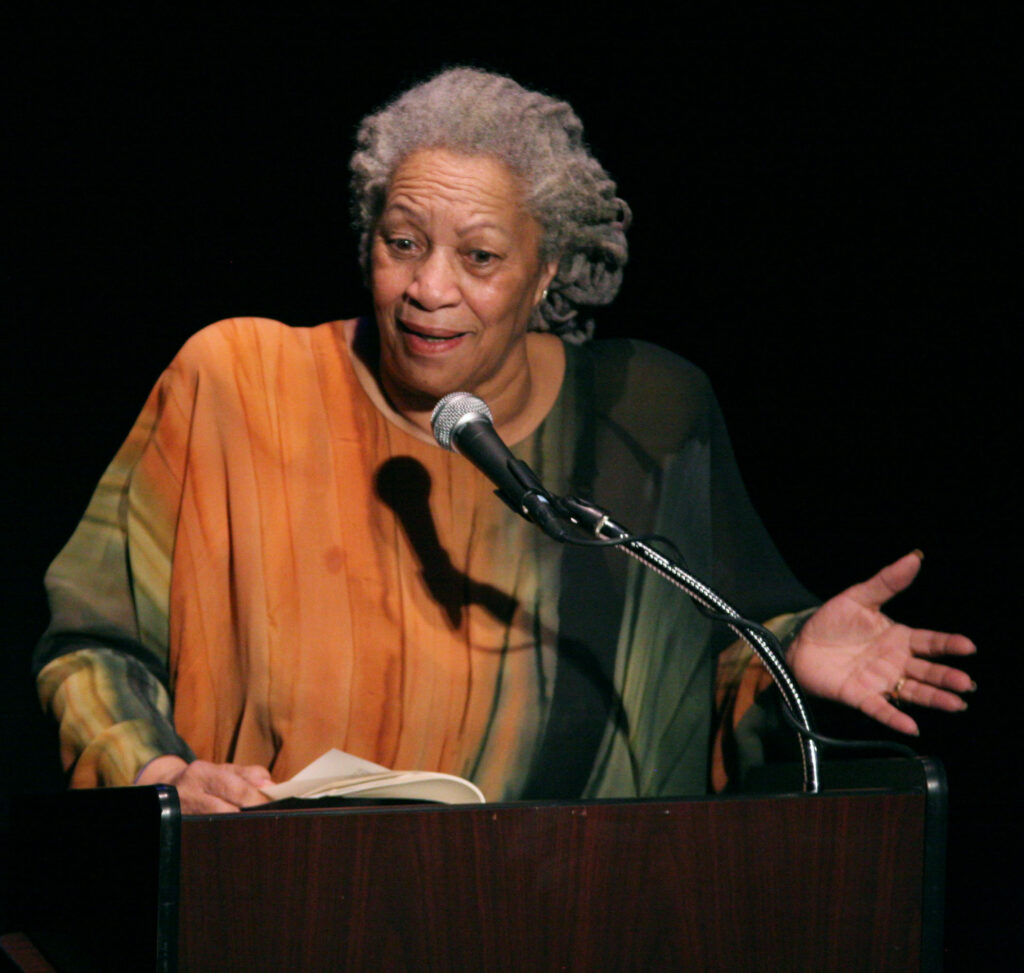

Remember those books that just stick with you? The ones that make you think, feel, and maybe even a little bit uncomfortable, but in the best possible way? Well, get ready to dive into one of *those* literary giants: Toni Morrison’s *Beloved*. This isn’t just a book you read; it’s an experience that stays with you, sparking conversations, challenging perspectives, and reminding us of the profound power of storytelling.

*Beloved* isn’t just a novel; it’s a cultural phenomenon. It’s won prestigious awards, inspired generations of readers and writers, and even stirred up significant debate, landing it on — and sometimes off — school reading lists. But beyond the accolades and controversies, at its heart, it’s a deeply human story, one that bravely confronts the darkest chapters of American history with an unflinching gaze and a vibrant, unforgettable voice.

So, buckle up, because we’re taking a deep dive into 15 incredible aspects of *Beloved* that make it an absolutely essential read. From its real-life origins to its groundbreaking themes and unforgettable characters, prepare to see why this masterpiece continues to resonate so powerfully today. Let’s unpack the magic, the heartbreak, and the undeniable genius of Toni Morrison.

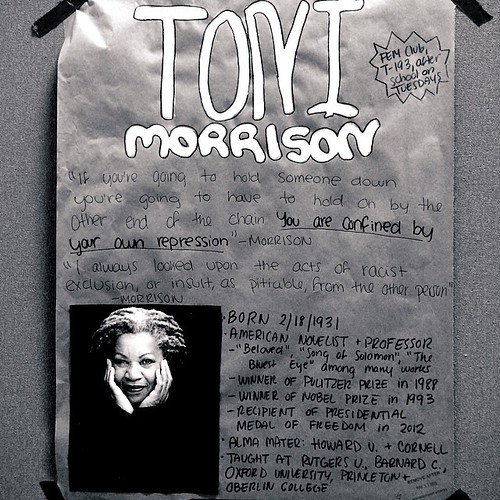

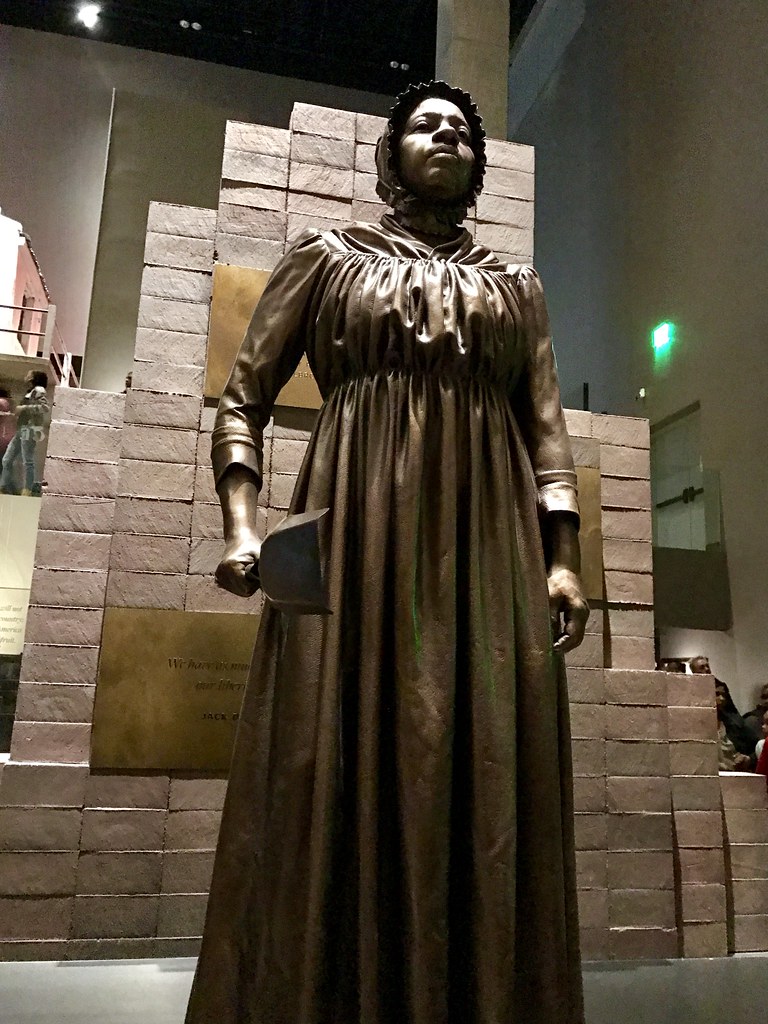

1. **The Chilling True Story That Sparked It All: Margaret Garner** It’s hard to believe that the deeply unsettling core of *Beloved* isn’t purely fiction. Toni Morrison’s main inspiration for the novel came from the life of Margaret Garner, a real-life enslaved woman whose story is as heartbreaking as it is defiant. Garner’s harrowing journey from Kentucky, a slave state, to the free state of Ohio in 1856, set the stage for Sethe’s own desperate flight.

Margaret Garner’s story took a tragic turn when she was subject to capture under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. When U.S. marshals broke into the cabin where she and her children had barricaded themselves, Garner made an unimaginable choice. She was attempting to kill her children, and had already killed her youngest daughter, in hopes of sparing them from being returned to the brutal life of slavery. This act, born of a mother’s desperate love and a terror of re-enslavement, is the powerful, agonizing crucible from which Sethe’s story emerges.

Morrison herself stumbled upon an account of this event titled “A Visit to the Slave Mother who Killed Her Child.” It was initially published in an 1856 newspaper article in the American Baptist and later reproduced in *The Black Book*, an anthology of texts of Black history and culture that Morrison had edited in 1974. This historical echo chamber of trauma and resistance became the fertile ground for her masterpiece.

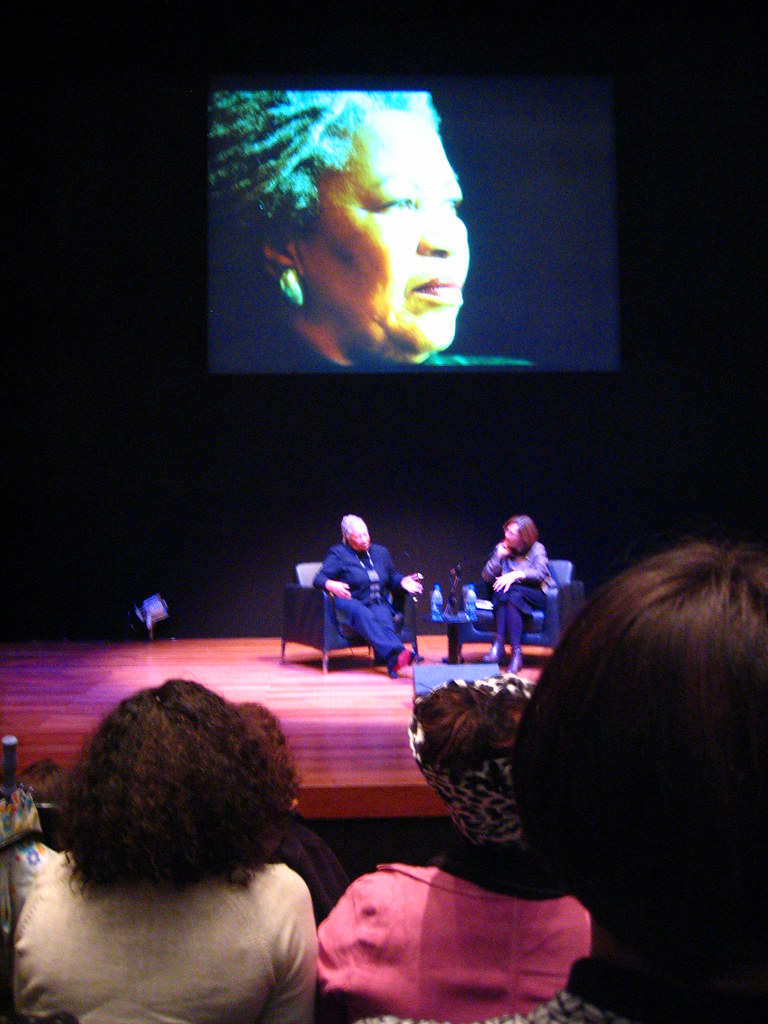

2. **A Literary Powerhouse: Pulitzer Prize and Widespread Acclaim** Just a year after its publication, *Beloved* wasn’t just a book; it was a phenomenon, recognized with one of the literary world’s highest honors. The novel won the prestigious Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, cementing its place in the literary canon and signaling its profound impact on readers and critics alike. It was also a finalist for the 1987 National Book Award, a testament to its immediate and undeniable significance.

But the accolades didn’t stop there. Over the years, *Beloved* continued to be recognized as a groundbreaking work. A survey of writers and literary critics compiled by *The New York Times* ranked it as the best work of American fiction from 1981 to 2006. This kind of consistent, long-term praise underscores its enduring power and its critical role in shaping contemporary American literature.

Its powerful narrative also caught the attention of Hollywood, leading to a major adaptation. The novel was brought to the big screen as a 1998 movie of the same name, starring none other than the iconic Oprah Winfrey. This adaptation further broadened its reach, introducing the story to an even wider audience and sparking new conversations about its themes and characters.

3. **The Haunting Dedication: “Sixty Million and More”** Even before the story truly begins, *Beloved* makes a profound statement with its dedication: “Sixty Million and more.” This powerful phrase isn’t just a number; it’s a haunting echo, referring to the untold millions of Africans and their descendants who perished as a direct result of the horrific Atlantic slave trade. It sets a somber and weighty tone, immediately grounding the reader in the immense historical tragedy that underpins the narrative.

This dedication serves as a stark reminder of the massive human cost of slavery, a statistic so staggering it’s almost incomprehensible. It forces us to confront the sheer scale of the atrocity, urging us to remember those whose lives were brutally cut short or irrevocably altered by this inhumane system. Morrison doesn’t just tell a story; she demands remembrance, providing a memorial where none officially existed.

The book’s epigraph, drawn from Romans 9:25 (King James Bible), further deepens this spiritual and historical resonance: “I will call them my people, which were not my people; and her beloved, which was not beloved.” This biblical reference foreshadows the novel’s exploration of identity, belonging, and the redemptive, albeit painful, journey towards self-acceptance and community, especially for those who were dehumanized and cast aside.

Read more about: Toni Morrison’s “Beloved”: An Enduring Masterpiece’s Unflinching Exploration of Slavery’s Profound Scars

4. **A Ghost Story Unfolding: The Plot’s Gripping Beginnings** The novel opens in 1873 in Cincinnati, Ohio, immediately plunging us into the unsettling world of Sethe, a formerly enslaved woman. She lives at 124 Bluestone Road with her 18-year-old daughter, Denver, in a home that has been haunted for years. The malevolent spirit, they believe, is that of Sethe’s eldest daughter, creating an atmosphere of dread and isolation that permeates their lives.

The haunting has had a tangible impact on the family. Denver is portrayed as shy, friendless, and housebound, trapped by the specter. Sethe’s sons, Howard and Buglar, couldn’t endure the supernatural presence and ran away from home by the age of 13, a decision Sethe sadly attributes to the ghost. Further deepening the sense of loss, Baby Suggs, Sethe’s mother-in-law, died eight years before the novel begins, soon after the boys fled.

A pivotal shift occurs with the arrival of Paul D, one of the enslaved men from Sweet Home, the plantation where Sethe, Halle, and Baby Suggs were once held captive. He forces out the oppressive spirit, much to Denver’s initial contempt, as she feels he’s driven away her only companion. Paul D, however, brings a glimmer of hope and connection, persuading Sethe and Denver to leave the house together for the first time in years to attend a carnival.

But the respite is short-lived. Upon their return, they find a young woman sitting in front of the house who calls herself Beloved. Paul D is immediately suspicious, sensing something off about her, and warns Sethe. However, Sethe, perhaps swayed by a deep longing or a mother’s intuition, is charmed by the young woman and chooses to ignore his apprehension. Denver, starved for companionship and connection, is eager to care for the sickly Beloved, gradually beginning to believe that this mysterious stranger is her older sister, returned from the dead.

As Beloved’s presence grows, Paul D begins to feel increasingly uncomfortable, sensing he’s being deliberately driven out of the house. One night, Beloved corners him, making a deeply unsettling demand to touch her on her “inside part.” During their intimate encounter, Paul D is overwhelmed by horrific memories from his past, including the sexual violence he and other men suffered while in a chain gang. He tries to confide in Sethe but struggles to articulate his trauma, instead blurting out his desire to have a baby with her. When Paul D shares his plans for a new family with his friends at work, their fearful reactions prompt Stamp Paid, a community elder, to reveal the reason for the community’s long-standing rejection of Sethe by showing Paul D a newspaper clipping. This article reveals the shocking truth about a fugitive woman who killed her child, bringing the story’s central tragedy to light for Paul D.

5. **Unpacking the Core: Mother-Daughter Relationships** At the heart of *Beloved* lies a searing examination of mother-daughter relationships, particularly as they are distorted and challenged by the brutal legacy of slavery. The maternal bonds between Sethe and her children, while deeply loving, paradoxically inhibit her own individuation and prevent the development of her true self. Sethe develops a dangerous maternal passion, a desperate drive to protect, that ultimately leads to the tragic killing of her eldest daughter—an act she believes is saving her “best self” from a life of bondage.

In the relative freedom of Ohio, Sethe continues to struggle with the aftermath of her past. She fails to recognize her surviving daughter Denver’s crucial need for interaction with the Black community, an essential step for Denver to fully enter into womanhood. Both the tragic infanticide and Denver’s subsequent isolation are direct outcomes of Sethe’s desperate attempts to salvage her “fantasy of the future,” her children, from the horrors of slavery. This intense, almost suffocating love, born of unimaginable trauma, creates its own set of problems.

However, the novel also portrays a powerful journey of healing and growth. At the end of the novel, with the help of Beloved’s mysterious arrival and subsequent departure, Denver succeeds in establishing her own self and embarking on her individuation, forging connections with the wider community. Sethe, too, only becomes truly individuated after Beloved’s exorcism. She is then free to fully accept the first relationship that is completely “for her,” her profound connection with Paul D, which offers her a path forward, relieving her from the self-destruction she was unknowingly causing based on her overwhelming maternal bonds.

The emotional impairment experienced by both Beloved and Sethe stems directly from Sethe’s enslavement. Under the cruel system of slavery, mothers were routinely stripped of their children, leading to devastating consequences for both parent and child. Baby Suggs, Sethe’s mother-in-law, coped with this by refusing to become too close to her children, remembering what she could of them as a protective measure. Sethe, however, desperately tried to hold onto her children and fight for them, even to the extreme point of taking their lives so they could be free from slavery’s clutches. This stark contrast highlights the different, yet equally painful, coping mechanisms forced upon enslaved mothers.

One of the most profound traumas for Sethe was having her milk stolen, a violation that not only deprived her of physical sustenance but also symbolically severed the fundamental bond between herself and her daughter by preventing her from feeding her. This act of dehumanization is a recurring motif, underscoring how slavery attacked the very essence of motherhood and the natural, nurturing connections that define it. The novel thus delves deep into how slavery warped the most fundamental human relationships.

6. **The Echoes of Trauma: Psychological Effects of Slavery** The enduring psychological scars of slavery form a central, haunting theme in *Beloved*. For most former slaves, the immense suffering under bondage led to a desperate attempt to repress and forget the past. This repression, this dissociation from the traumatic memories, resulted in a fragmentation of the self and a profound loss of true identity. Sethe, Paul D, and Denver all experienced this deep-seated loss of self, a void that could only begin to be remedied when they were finally able to confront and reconcile their pasts and memories of earlier identities.

The enigmatic character of Beloved serves as a powerful catalyst in this painful process. She acts as a living, breathing reminder for these characters, forcing their repressed memories to the surface. Her presence, while disruptive and ultimately consuming, eventually leads to a necessary, albeit agonizing, reintegration of their fragmented selves. It’s through her that the past, no longer silent, demands to be heard and reckoned with.

Slavery, as depicted in the novel, shatters a person into a fragmented figure, a “self that is no self.” This identity, burdened by painful and unspeakable memories, is denied and kept at bay, creating an internal chasm. To heal and to humanize oneself, one must constitute this fractured self in a language, reorganize the painful events, and retell the agonizing memories. The “self” becomes subject to a violent practice of making and unmaking; only when acknowledged by an audience does it begin to become real again.

Sethe, Paul D, and Baby Suggs all fall short of this full realization for a time, unable to remake themselves precisely because they try to keep their pasts at bay, holding on to an illusion of an “uncomplicated past.” The “self” is often located in a word, defined by others, and power lies in that word—once the word changes, so does the identity. All of the characters in *Beloved* face the immense challenge of an unmade self, composed of their “rememories” and defined by perceptions and language imposed upon them.

The formidable barrier that keeps them from the remaking of the self is this deep-seated desire for an “uncomplicated past” and the terrifying fear that truly remembering will lead them to “a place they couldn’t get back from.” Morrison expertly explores this psychological minefield, showing how the past is not merely gone but lives on, profoundly shaping the present. The novel underscores that confronting these deeply buried traumas, however painful, is the only path to genuine freedom and self-possession.

7. **Redefining Manhood: Paul D’s Struggle for Identity** The novel offers a profound and nuanced discussion of manhood and masculinity, particularly as these concepts are shattered and rebuilt in the aftermath of enslavement. The overarching meaning of Sethe’s story, while central, is expertly intertwined with the experiences of men like Paul D. *Beloved* portrays slavery not just through the lens of love and self-preservation, but also through its devastating capacity to distort a man from himself, challenging his very essence.

Morrison meticulously depicts the horrors of enslavement and its lasting effects, communicating powerful morals about the definition of manhood. She skillfully uses stylistic devices to reveal different pathways to understanding what manhood means when constantly under assault. To immerse the audience in Paul D’s internal world, Morrison deliberately inserts his half-formed words and fragmented thoughts, offering a raw taste of his inner turmoil and ongoing struggle to define himself.

Throughout the novel, Paul D’s perception of manhood is relentlessly challenged by the prevailing norms and values of white culture, which sought to dehumanize and diminish Black men. Morrison masterfully demonstrates the distinctions between Western and African values, and how the dialogue, or often conflict, between these two value systems is expressed through striking juxtaposition and evocative allusions. Scholar Zakiyyah Iman Jackson compellingly argues that Paul D’s reduced manhood emerges in direct relation to a discourse of animality, reflecting how enslaved men were often stripped of their humanity and relegated to a lesser status.

Paul D embodies the tragic victim of racism, a man whose dreams and goals, once so high and fervent, remain tragically out of reach because of the pervasive systemic racism of his era. He believes he has earned his right to pursue these goals through his immense sacrifices and unimaginable suffering, holding onto the hope that society would eventually compensate him and allow him to fulfill his heart’s desires. Yet, the harsh reality of post-slavery America repeatedly denies him this right, crushing his spirit and challenging his very sense of self-worth.

In the era following Reconstruction (1890–1910), Jim Crow laws were systematically put in place to severely limit the movement and involvement of African Americans in the White-dominant society. Black men during this tumultuous time were forced to forge their own identities within an oppressive framework, a task that often seemed impossible due to the myriad limitations imposed upon them. Many Black men, much like Paul D, struggled profoundly to find meaning and achieve their goals in a society that constrained them to a “lower-status” position based solely on the color of their skin. Stamp Paid’s poignant observation of Paul D, sitting on the base of the church steps, “…liquor bottle in hand, stripped of the very maleness that enables him to caress and love the wounded Sethe…,” powerfully illustrates this emasculation. The recurring image of Paul D sitting on a ‘base’ or ‘foundation’—like a tree stub or the church steps—symbolically exemplifies his foundational but subjugated place in society, highlighting how Black men were coerced into a system that depended on their labor but denied them their rightful humanity and standing.

8. **The Complexities of Family Relationships Under Duress**Family isn’t just a theme in *Beloved*; it’s the very soul of the narrative, revealing the immense stress and systematic dismantlement of African-American families during and after slavery. The brutal reality of the system meant that enslaved individuals had no rights to themselves, their loved ones, or their children. This profound lack of agency sets the stage for Sethe’s unimaginable act, where killing her daughter was, in her mind, a desperate act of salvation, a twisted form of peace to spare her child from the horrors of enslavement. It’s a stark portrayal of a mother’s love pushed to its absolute breaking point.

This desperate act, however, shatters the family further, leaving it fragmented and bruised, much like the post-Emancipation era itself. The novel vividly illustrates how formerly enslaved families were left reeling from the hardships and trauma they endured. Their very structures were irrevocably altered, forcing them to find new, often painful, ways to define what ‘family’ truly meant.

Adding another layer to these already complex relationships, the novel hints at the significant role of the supernatural in the lives of enslaved people. Cut off from societal events, many placed their faith and trust in spiritual beliefs, rituals, and prayers. Beloved’s mysterious arrival, after Sethe, Denver, and Paul D return from a rare social outing at the carnival, is a direct manifestation of this intersection between profound familial trauma and the spiritual realm. She embodies the fractured family bond, haunting Sethe and forcing a reckoning with an unspeakable past.

This ghostly presence, believed by Sethe to be her murdered daughter, becomes a central means through which the novel explores mental strife. Beloved is not just a character; she’s a living embodiment of memory, grief, and the agonizing space between Sethe and her lost child. Her presence in the house, a place meant for warmth and vulnerability, forces other characters like Paul D and Baby Suggs to confront the pain Sethe tries to suppress, highlighting how deeply slavery warped the most fundamental human connections.

Read more about: The ’90s Called, They Want Their Laughs Back! Unpacking 10 Hilariously Iconic Comedy Movies That Still Rule Your Rewatch List

9. **The Universality and ‘Romanticization’ of Pain**Oh, the pain! It courses through *Beloved* like a river, touching every single character and leaving indelible scars—physical, mental, sociological, psychological. It’s a universal suffering, a systematic torture that people who had been enslaved had to navigate even after the Emancipation Proclamation. Morrison doesn’t shy away from depicting this immense hurt, but she also delves into the complex ways characters try to cope, sometimes even attempting to ‘romanticize’ their pain as a turning point in their lives, a concept with echoes in early Christian contemplative tradition and African-American blues.

The novel’s narrative itself is a complex labyrinth, reflecting how characters have been ‘stripped away’ from their voices, their stories, their very language, leaving their sense of self diminished. Each character’s experience with slavery is distinct, carving out unique stories and narratives within this overarching landscape of suffering. It’s a powerful reminder that trauma is deeply personal, even when experienced collectively.

One of the most striking examples of attempting to ‘beautify’ pain is Sethe’s insistence on describing the brutal whip scars on her back, not as ugly wounds, but as a ‘Choke-cherry tree. Trunk, branches, and even leaves.’ She repeats this description to everyone, desperately seeking to find beauty in her pain, a testament to the human spirit’s desire for meaning even in the face of immense trauma. Yet, the reactions of Paul D and Baby Suggs—their disgust and denial of this description—poignantly underscore the inherent ugliness of the act that caused such scars.

Similarly, Sethe’s interaction with Beloved embodies this complex relationship with pain. She sees Beloved, all grown and alive, not as a reminder of the agony of infanticide, but as her lost child returned. Paul D and Baby Suggs, however, recognize Beloved as an uninvited, painful presence in their home. It’s only at the novel’s end, when Beloved is gone and Paul D encourages Sethe to love herself, that Sethe begins to question her self-destructive embrace of past suffering, starting a path toward healing.

10. **Heroism in the Face of Opposition: Sethe and Denver’s Journey**Forget capes and superpowers; in *Beloved*, heroism is redefined as the ability to do what one believes is right, even when the world—or your community—stands against you, and to inspire others to break free from the past’s painful grip. This novel challenges the idea that heroism is absolute, showing instead how it’s relative to past experience and the profound influence of community. Sethe and Denver, our two powerful female leads, are perfect examples of this unconventional heroism.

Sethe, in particular, is far from a conventional hero. Her shocking decision to kill her own child, Beloved, is met with scorn and condemnation from the community. Yet, Sethe never wavers in her conviction, stating, “It ain’t my job to know what’s worse. It’s my job to know what is and to keep them away from what I know is terrible. I did that.” She starkly contrasts society’s expectation—to peacefully deal with Schoolteacher’s return—with her self-assigned role: to protect her children from the venomous anguish of slavery, even if it means death. For Sethe, death was truly preferable to a life in bondage.

But Sethe’s heroism isn’t just about her defiant act; it also extends to helping others heal. We see this powerfully when she helps Paul D grapple with his own agonizing past. Paul D recalls her tenderness about his iron bit, how she ‘never mentioned or looked at it, so he did not have to feel the shame of being collared like a beast.’ This seemingly small act of non-acknowledgment allowed Paul D to retain his sense of manhood, a core part of his identity that slavery had tried to strip away. Her understanding, though unspoken, was a profound act of support.

Then there’s Denver, who embarks on her own heroic journey, breaking free from the suffocating isolation of 124 Bluestone Road. Trapped by her past and the haunting presence, Denver finds the courage to step beyond the house and seek help from the community she’d been alienated from. When she realizes that ‘neither Beloved nor Sethe seemed to care what the next day might bring. Denver knew it was on her. She would have to leave the yard; step off the edge of the world, leave the two behind and go ask somebody for help,’ it’s her tipping point. This metaphorical ‘stepping off the edge of the world’ vividly illustrates her immense courage to forge a new path for herself and her mother.

Denver’s actions are not just personal; they are transformative for the community. She assumes a maternal role, caring for Sethe and inspiring Ella to rally a group of women to exorcise Beloved. Their united voices, compared to a ‘wave of sound wide enough to sound deep water and knock the pods off chestnut trees,’ demonstrate the incredible power of a community working together. Through Denver’s bravery, Sethe is cleansed and freed from Beloved’s oppressive grip, underscoring Morrison’s message that true heroism lies in resisting societal norms, standing up for one’s beliefs, and positively influencing others.

11. **Sethe: The Resilient Protagonist, Scars and All**Our protagonist, Sethe, is the beating heart of *Beloved*, a formerly enslaved woman who escaped the horrors of the Sweet Home plantation. She lives at 124 Bluestone Road, a place haunted not just by a ghost, but by the weight of her own past—the unfathomable act of killing her infant child to spare her from slavery. This trauma has driven her sons away and left her with only her daughter, Denver, for companionship, yet it defines her fierce, protective motherhood. Sethe is, in every sense, resilient, but her character is irrevocably shaped by the unspeakable experiences she endured.

Sethe is maternal in the most intense way imaginable, willing to do anything to shield her children from the same abuses she suffered. She carries her trauma literally, with ‘a tree on her back’—the horrific scars from being whipped. This image is not merely physical; it’s a profound symbol of the lasting emotional and psychological wounds of slavery that she struggles to repress. Born in 1836, she was just 19 when Denver was born, marking a life steeped in the cruel realities of bondage from an early age.

Her repression of trauma creates a complex inner world, where memories, or ‘rememories’ as she calls them, don’t just fade but live on, shaping her present. Sethe’s journey is one of profound internal conflict, caught between a desperate need to forget the past and the impossibility of doing so. Her unwavering conviction in her actions, however tragic, speaks volumes about her strength and her unique definition of love and protection.

Read more about: Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’: An In-Depth Examination of Its Haunting Narrative, Complex Characters, and Profound Themes

12. **Beloved: The Mysterious Catalyst and Haunting Presence**Beloved. Her very name, derived from the single word Sethe could afford on her murdered baby’s tombstone, is steeped in tragedy and mystery. The novel’s central enigma, Beloved appears out of nowhere, soaking wet by a body of water, and is found on Sethe’s doorstep after a carnival outing. She’s taken in, and immediately, the haunting at 124 Bluestone Road ceases, fueling the pervasive belief that she is the murdered baby, returned to her mother.

Her character is deliberately opaque, a vessel for both profound remembrance and unsettling madness. She behaves in many ways like a child, yet possesses an ancient, knowing quality. Beloved serves as a powerful catalyst, forcing the repressed traumas of Sethe, Paul D, and Denver to the surface. Her arrival disrupts the fragile peace, demanding an accounting for the past and compelling the characters to confront their deepest, most buried pains.

Yet, Beloved’s presence is not purely redemptive. As she grows increasingly demanding and consumes Sethe’s life—her time, her money, her very essence—she begins to embody the destructive power of unresolved trauma. She grows physically, even taking the form of a pregnant woman, mirroring Sethe’s own state when she fled Sweet Home, and symbolizing the unending cycle of past burdens. Her actions ultimately deplete Sethe, highlighting the dangerous cost of clinging too tightly to a ghost, however beloved.

Morrison herself stated that Beloved *is* the daughter Sethe killed, clarifying the supernatural core of the character while still allowing for critical debate about her nature. Beloved’s presence forces a difficult reckoning, pushing Sethe to the brink, but ultimately paving the way for Denver’s growth and the community’s intervention, leading to her eventual, necessary disappearance and Sethe’s path toward self-love.

Read more about: Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’: An In-Depth Examination of Its Haunting Narrative, Complex Characters, and Profound Themes

13. **Denver: From Shy Isolation to Protective Womanhood**Denver, Sethe’s only surviving child who remains at 124, begins the novel as a shy, friendless, and housebound young woman. Isolated from the Black community after the infanticide and further by the oppressive haunting, she initially forms an intense, almost suffocating bond with her mother. She’s a child of immense trauma, her early life shaped by the lingering specter of her older sister’s ghost, which she initially viewed as her only companion.

Her world is tiny and contained, centered around her mother and the haunted house. When Beloved arrives, Denver is starved for connection and companionship. She eagerly embraces the mysterious young woman, caring for her and quickly coming to believe that this stranger is her older sister, returned from the dead. This new bond, while initially fulfilling a deep need, also traps her in the cycle of her family’s trauma and the growing madness within 124.

However, Denver undergoes one of the most significant character arcs in the novel. As Beloved’s influence becomes increasingly detrimental, consuming Sethe and plunging the house into chaos, Denver realizes she must break the cycle. She evolves from a childish, passive figure into a fiercely protective woman, fighting not only for her own independence but for her mother’s well-being. This pivotal shift leads her to courageously seek help from the community, shattering her long-standing isolation and demonstrating remarkable growth and resilience.

Read more about: Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’: An In-Depth Examination of Its Haunting Narrative, Complex Characters, and Profound Themes

14. **Baby Suggs and Halle: Community Wisdom and Tragic Disappearance**Baby Suggs, Sethe’s mother-in-law, is a formidable figure, a beacon of wisdom and community leadership whose freedom was bought by her son, Halle. Once free, she traveled to Cincinnati and quickly established herself as a respected matriarch, preaching powerful messages of self-love to the Black community, encouraging them to embrace their own worth when the white world refused to. Her ‘Clearing’ sermons, where people gathered to express their emotions and find solace, were a vital part of the community’s spiritual and emotional life.

However, her respected position took a tragic turn. An act of generosity—turning some food into an extravagant feast—stirred envy in the community, and this, coupled with Sethe’s unspeakable act of infanticide, caused Baby Suggs to withdraw. Disillusioned and heartbroken by the community’s judgment and the overwhelming pain of the world, she retired to her bed, choosing to spend her remaining eight years contemplating only ‘pretty colors,’ a poignant retreat from the harsh realities of existence. Her death, eight years before the main events of the novel, leaves a void of spiritual guidance.

Halle, Baby Suggs’ son and Sethe’s husband, is a haunting presence through flashbacks. He worked tirelessly to buy his mother’s freedom, a testament to his good nature and hardworking spirit. Paul D was the last to see him at Sweet Home, churning butter, and it’s heavily implied that Halle went mad after witnessing the horrific violation of Sethe by Schoolteacher’s nephews. His disappearance and presumed descent into madness underscore the devastating psychological toll of slavery on men, leaving Sethe to carry their collective burden and further fragmenting their family.

15. **Critical Acclaim, Enduring Legacy, and Lingering Controversies**While *Beloved* won the Pulitzer Prize shortly after its publication, its critical reception was complex, cementing its place not just as a literary achievement but as a lightning rod for debate. In fact, when it initially lost the National Book Award in 1987, a powerful letter of protest, signed by 48 African-American writers and critics including luminaries like Maya Angelou and Angela Davis, was published in *The New York Times Book Review*, demanding recognition for its profound significance. This collective voice underscored the novel’s immediate and undeniable impact on the literary world and Black intellectual thought.

Beyond awards like the Pulitzer, the Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Book Award, and the Melcher Book Award, *Beloved*’s legacy is perhaps best encapsulated by Toni Morrison’s own words. Upon accepting the Melcher Book Award, Morrison lamented the absence of a proper memorial for the millions who died in the Atlantic slave trade. Her poignant statement, ‘There’s no small bench by the road,’ directly inspired the Toni Morrison Society to establish ‘bench by the road’ memorials at significant sites of slavery history across America, transforming a literary lament into a tangible act of remembrance and cultural footprint.

The novel has also sparked extensive scholarly debate, particularly concerning the character of Beloved herself. Is she truly a ghost, the literal incarnation of Sethe’s murdered daughter, or a real person whose identity has been mistaken? Critics like Elizabeth B. House argue for the latter, suggesting Beloved is not a ghost, which reframes many ‘puzzling aspects’ and emphasizes Morrison’s focus on familial ties. This ongoing discussion highlights the novel’s depth and its capacity for varied, profound interpretations, pushing readers and scholars alike to consider the complex interplay of memory, identity, and history.

And let’s be real, a book this powerful isn’t without its share of controversy, especially in the realm of education. *Beloved* has faced numerous attempts at banning in U.S. schools, often cited for its graphic descriptions of sex, violence, and infanticide. Notable instances, like its temporary ban at Eastern High School in Kentucky and its role in inspiring Virginia’s ‘Beloved Bill’—legislation requiring parental notification for ‘sexually explicit content’—underscore its continued ability to provoke discussion and discomfort. This persistent controversy is, in a way, another testament to the novel’s enduring power; it forces uncomfortable but necessary conversations about America’s past and how we choose to confront it in our present.

Read more about: Olivia Hussey: A Life Defined by Star-Crossed Romance, Acclaim, and Lingering Controversy (1951-2024)

Truly, *Beloved* is more than just a book; it’s a living, breathing testament to the human spirit’s resilience in the face of unspeakable cruelty. It’s a reminder that history isn’t just dates and facts, but a tapestry woven with the searing ‘rememories’ of individuals who fought, loved, and survived. Morrison’s masterpiece challenges us to confront the darkest corners of our past, to acknowledge the pain, and to find the heroism in healing and community. It’s a story that echoes across generations, urging us to remember, to understand, and to ensure that ‘sixty million and more’ are never forgotten.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(919x599:921x601)/kelly-clarkson-brandon-blackstock-1-9eabc0058e1a4b6c8bc26e0923da6cfd.jpg)