The 1990s. For many, it evokes images of grunge music, the burgeoning internet, and a hopeful post-Cold War world. Yet, beneath the surface of cultural shifts and technological marvels, it was a decade defined by profound geopolitical realignments and assertive displays of power, shaping global dynamics in ways that reverberate even now. It was a time when the world population surged from 5.3 to 6.1 billion, a period of both immense growth and significant conflict.

This era saw the United States emerge as the world’s sole superpower following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, leading to a new global order. Accompanying this shift were prevailing attitudes and approaches—what we might call ‘power personas’—that, while perhaps effective or accepted at the time, were intrinsically tied to the specific circumstances of the Nineties. These personas often reflected a direct, sometimes confrontational, and frequently dominant approach to international relations, economic policy, and even social dynamics. The very fabric of society was changing with greater attention to multiculturalism and the advance of alternative media.

As we navigate the complexities of the 21st century, it becomes strikingly clear that many of these defining ’90s power personas, if resurrected without adaptation, would simply fail to resonate or even cause outright rejection. The world has evolved, and the seeds of that evolution were often sown in the ’90s themselves, through the proliferation of new media like the internet, and growing public discourse around issues like human rights and environmentalism. We’re diving into ten such personas, beginning with five that powerfully illustrate this fascinating temporal disconnect.

1. **The Sole Superpower Persona**One of the most defining characteristics of the 1990s was the dramatic reshaping of the global power landscape, leading directly to the emergence of what we term the “Sole Superpower Persona.” With the monumental dissolution of the Soviet Union on December 26, 1991, Russia’s status as a superpower effectively ended. This pivotal event didn’t just mark the end of a multipolar world; it ushered in an era where one nation stood preeminent. The context notes this directly, stating the US “emerged as the world’s sole superpower, creating relative peace and prosperity for many western countries.”

This newfound status fostered a certain kind of geopolitical confidence, an assumption of leadership that often manifested in direct, assertive foreign policy. From the Gulf War to the later interventions in the Balkans, the US, often leading international coalitions, was seen as the primary arbiter of global security and order. While this period did indeed bring “relative peace and prosperity for many western countries,” it also set a precedent for a more unilateral approach to international crises, driven by a perception of unchallenged authority. The world population, which grew from 5.3 to 6.1 billion during this decade, looked to this single power for stability, even as anti-Western sentiment began to rise elsewhere.

However, this “Sole Superpower Persona,” with its unquestioned global authority, would find the modern international stage far more challenging. The very “rise of anti-Western sentiment” mentioned in the context, though nascent in the ’90s, has significantly intensified. Today’s geopolitical landscape is increasingly fragmented, with a resurgence of multipolarity and complex power blocs. The internet, initially seen as a tool for connection, has also amplified diverse voices and challenged singular narratives, making a top-down, “sole superpower” approach far less palatable or effective.

Moreover, the 1990s also saw “greater attention to multiculturalism and advance of alternative media,” subtle shifts that hinted at a future demanding more inclusive, collaborative global governance. An assertive unilateralism, once accepted as necessary for post-Cold War stability, would now be met with widespread skepticism and pushback from a more informed and interconnected global citizenry. The unadulterated confidence of the “Sole Superpower Persona” would clash with a demand for shared responsibility and more equitable international relations.

Read more about: Beyond the Pages: 15 Jaw-Dropping Reasons Why Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’ Still Shakes the Literary World (and Our Hearts!)

2. **The Unchecked Neoliberal Capitalist Persona**The economic ethos of the 1990s was heavily dominated by what we identify as the “Unchecked Neoliberal Capitalist Persona.” This was a period defined by an enthusiastic embrace of market-driven policies, globalization, and the “mass-mobilization of capital markets through neoliberalism,” as the context highlights. With the end of the Cold War, the ideological battle between capitalism and communism was widely perceived as settled, paving the way for a rapid expansion of free-market principles across the globe.

This persona manifested in concrete policy actions, such as the establishment of major trade agreements like the European Union in 1993, NAFTA in 1994, and the World Trade Organization in 1995. These agreements facilitated unprecedented increases in international trade, fueling economic prosperity in “high-income countries” that experienced “steady growth during the Great Moderation.” The narrative of the decade was one of triumphant, unbridled economic expansion, where the free flow of capital and goods was seen as the ultimate engine of progress, often with little consideration for downsides.

However, the seeds of future discontent were also sown by this very persona. While many experienced prosperity, the context starkly notes that “the GDP of former Soviet Union states declined as a result of neoliberal restructuring.” This hints at the uneven distribution of benefits and the social upheaval that such rapid, unchecked economic shifts could cause. The “dot-com bubble of 1997–2000” also brought “wealth to some entrepreneurs before its crash of the early-2000s,” a stark reminder of the speculative risks inherent in this aggressive capitalist approach.

If this “Unchecked Neoliberal Capitalist Persona” were to operate with the same assumptions today, it would encounter significantly stronger resistance and scrutiny. The global financial crises of the 2000s and a heightened awareness of economic inequality have shifted public and political discourse dramatically. Modern sensibilities demand more regulated markets, greater social safety nets, and a stronger focus on equitable distribution of wealth. The once-celebrated unfettered market approach would now be widely criticized for its lack of social responsibility and potential to exacerbate divides.

3. **The Strongman Autocrat Persona**Throughout the 1990s, despite a global trend towards political liberalization, the specter of the “Strongman Autocrat Persona” persisted, demonstrating a tenacious grip on power in various regions. This persona represented leaders who ruled with an iron fist, often for decades, epitomizing concentrated, authoritarian control. The context provides striking examples, such as Mobutu Sese Seko, whose “32-year rule of Zaire” ended with his overthrow in the First Congo War. Similarly, “Indonesian President Suharto resigned after ruling the country for 32 years,” a tenure that only concluded in 1998 after widespread riots.

These leaders often maintained power through military force, political suppression, and cultivated public image, representing a traditional ‘macho’ governance. Their actions could be exceptionally brutal, as seen in the context’s mention of Saddam Hussein’s decision to invade Kuwait in 1990 after accusing them of oil market manipulation. Even in nascent democracies, elements of this persona could surface; Boris Yeltsin, the president of the Russian Federation, resorted to “ordering the controversial shelling of the Russian parliament building by tanks” during the 1993 Russian constitutional crisis, a stark display of forceful executive power.

However, the ’90s also contained the very forces that would chip away at the viability of the “Strongman Autocrat Persona.” The advent of the World Wide Web and the proliferation of “new media such as the internet” began to challenge traditional control over information. While the “digital divide was immediate,” limiting access initially, the foundations were laid for an era where state narratives would be harder to maintain. The rise of international human rights advocacy, though not explicitly detailed as a 90s movement in the text, is implicitly contrasted by the sheer number of documented genocides and war crimes mentioned, which eventually garnered global condemnation.

In today’s interconnected world, the “Strongman Autocrat Persona” would face unprecedented scrutiny and widespread public resistance. Global media, fueled by social platforms and instant communication, would relentlessly expose abuses of power. International sanctions and diplomatic pressure would be more readily mobilized. While such figures regrettably still exist, their ability to maintain absolute power and control public perception without significant challenge has dramatically diminished compared to the relative insulation enjoyed by some autocrats in the 1990s. The global landscape demands accountability, transparency, and adherence to human rights, making overt displays of autocratic might much less sustainable.

4. **The Unilateral Interventionist Persona**The 1990s, particularly after the Cold War, frequently showcased what can be described as the “Unilateral Interventionist Persona” in international affairs. This attitude was characterized by the readiness of powerful nations, often led by the United States, to deploy military force or exert significant influence in global conflicts, sometimes with robust international backing, and at other times, with less consensus. The Gulf War exemplifies the former, where the UN “immediately condemned the action” of Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, leading to a “coalition force led by the United States” decisively driving the Iraqi army out.

While the Gulf War had UN approval, the decade progressed to demonstrate instances where interventionist actions were taken with less universal endorsement, highlighting a more assertive and independent stance. The Kosovo War stands as a prime example of this persona’s later manifestation. In 1999, “NATO, led by the United States, launched air attacks against Yugoslavia” to address atrocities in Kosovo. Crucially, the context points out that “The intervention lacked UN approval yet was justified by NATO based on accusations of war crimes committed by Yugoslav military forces working alongside nationalist Serb paramilitary groups.”

This “Unilateral Interventionist Persona,” though driven by humanitarian or strategic interests, assumed powerful actors could determine the necessity and legality of interventions without full global institutional backing. The rapid and decisive nature of such actions, like the four-day expulsion of the Iraqi army from Kuwait, reinforced a perception of military might as the ultimate solution to complex problems. Such actions were presented as decisive and necessary, aligning with a more ‘macho’ approach to conflict resolution.

However, the present global climate would render the “Unilateral Interventionist Persona” far more problematic and less effective. The experiences of subsequent decades, and the complexities that often follow such interventions, have led to increased caution and a greater emphasis on multilateralism and international law. The “advance of alternative media” and the widespread reach of the internet mean that military actions are subjected to instantaneous and global scrutiny, challenging the narratives of intervening powers. An intervention lacking UN approval today would provoke far more widespread and sustained international condemnation and domestic dissent than in the 1990s, highlighting a shift towards diplomacy and consensus-building over swift, independent military action.

5. **The Dogmatic Nationalist Persona**The 1990s, while a decade of globalization, was paradoxically marred by the rise of the “Dogmatic Nationalist Persona.” This virulent strain of identity politics, characterized by an aggressive assertion of ethnic or national identity, often led to brutal conflicts and mass atrocities. The dissolution of multinational states, notably Yugoslavia, provided fertile ground for this persona to flourish. The context explicitly states that “Ethnic tensions and violence in former Yugoslavia during the 1990s created a greater sense of ethnic identity among nations in newly independent countries and a marked increase in the popularity of nationalism.”

The consequences of this persona were devastatingly real. The “Yugoslav Wars (1991–1995)” were “notorious for war crimes and human rights violations, including ethnic cleansing and genocide,” with Muslim Bosniaks suffering the most. Similarly, the “Rwandan genocide (1994)” stands as a horrific testament to dogmatic nationalism, where “hundreds of thousands of Rwanda’s Tutsis and Hutu political moderates were killed by the Hutu-dominated government under the Hutu Power ideology.” These events underscore a grim ‘macho’ assertion of group identity that prioritized perceived ethnic purity and dominance over human life and rights. Even conflicts like “The First Chechen War” between the Russian Federation and the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria had strong nationalist undertones.

While the ’90s witnessed these atrocities, the global response, though often slow or insufficient, began to highlight a growing international consciousness around such issues. The United Nations and major states “came under criticism for failing to stop the [Rwandan] genocide,” indicating that even then, there was an expectation for international bodies to act. This criticism itself marks a nascent rejection of extreme nationalism as an acceptable basis for state action, hinting at a future where such ideologies would face greater condemnation.

In today’s world, the “Dogmatic Nationalist Persona” would be met with an even more immediate and forceful global outcry. The internet, which provided “anonymity for individuals skeptical of the government” in the ’90s, has also become a powerful tool for documenting and exposing human rights abuses in real-time. International justice mechanisms have evolved, and the concept of state sovereignty as an absolute shield against intervention in cases of genocide and ethnic cleansing has weakened. While nationalism still exists, its most dogmatic and violent forms would now be almost universally condemned, facing swifter, more concerted international action, making such a persona far less tenable as a legitimate political force.

6. **The Post-Cold War Triumphalist Persona**The fall of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent dissolution of the Soviet Union on December 26, 1991, ignited a profound sense of ideological victory across the Western world, birthing what we’ve termed the ‘Post-Cold War Triumphalist Persona.’ This era was characterized by an almost giddy confidence in the triumph of liberal democracy and capitalism, as the “former countries of the Warsaw Pact moved from single-party socialist states to multi-party states with private sector economies.” It was a period where the world seemed to exhale a collective sigh of relief, imagining a future largely free from the existential dread of superpower confrontation, fostering “relative peace and prosperity for many western countries.”

This persona wasn’t just about political ideology; it permeated cultural and economic narratives. The context notes that “market reforms made incredible changes to the economies of Second World socialist countries such as China and Vietnam,” indicating a global embrace of market principles. There was a prevailing belief that the major questions of governance and economic organization had been answered, and the path forward was clear: globalization, free markets, and democratic expansion. This self-assuredness fueled a certain ‘macho’ swagger on the international stage, a feeling that history had delivered a definitive verdict in favor of one way of life.

Indeed, the 1990s presented a landscape where such triumphalism could genuinely take root. With the US as the “sole superpower,” there was a perceived vacuum in global leadership that was quickly filled by a confident, often assertive, Western agenda. This confidence, while perhaps understandable given the monumental shifts, often led to an underestimation of nascent challenges and complexities that were simultaneously emerging across the globe, including the subtle “rise of anti-Western sentiment” that the context hints at.

However, this ‘Post-Cold War Triumphalist Persona’ would utterly flop in today’s deeply interconnected and profoundly nuanced world. The simplistic narrative of a singular ideological victory has been shattered by a series of global financial crises, the enduring rise of diverse economic and political models beyond the Western paradigm, and the increasing recognition of systemic inequalities. That early “rise of anti-Western sentiment” has matured into a significant geopolitical force, challenging any presumption of universal acceptance for a Western-led global order.

Moreover, the “advance of alternative media” and the widespread reach of the internet mean that any top-down, triumphalist narrative would be met with immediate and critical global scrutiny. Today’s public demands a more humble, collaborative, and self-reflective approach to global affairs, acknowledging the complexities of different cultures and historical experiences. The unadulterated certainty of the ’90s triumphalist would appear tone-deaf and out of touch in an era that values dialogue and multilateralism over ideological pronouncements.

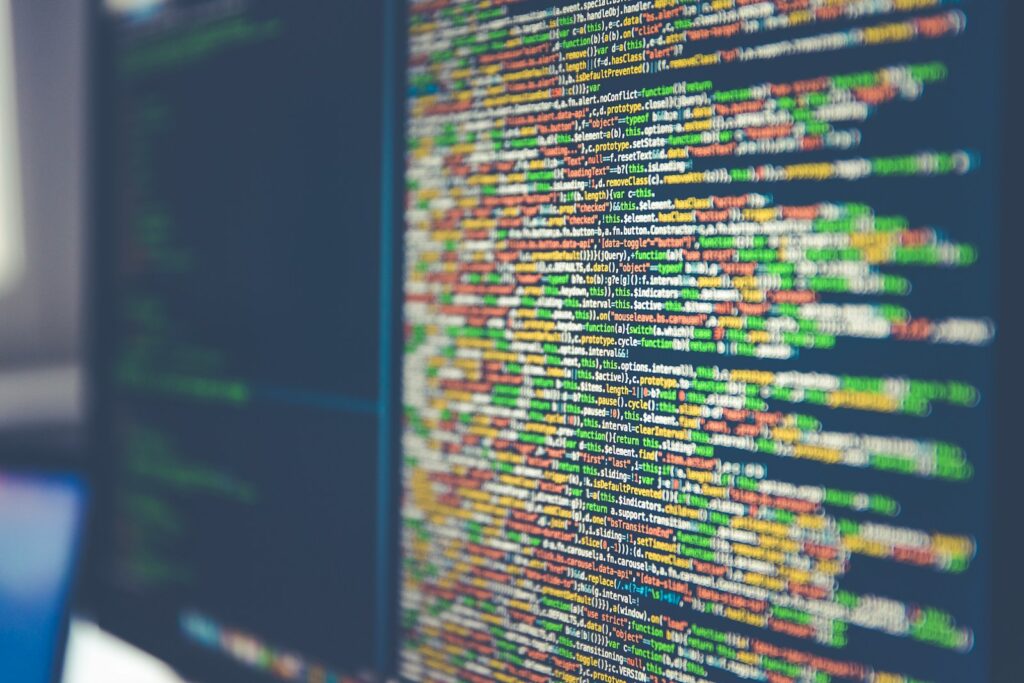

7. **The Dot-Com Bubble Entrepreneur Persona**The 1990s witnessed the birth of the internet as a mainstream phenomenon, giving rise to what we can call the ‘Dot-Com Bubble Entrepreneur Persona.’ This was a breed of ambitious, often young, innovators who saw the World Wide Web not just as a new technology but as a boundless frontier for unprecedented wealth creation. There was an exhilarating sense of being at the forefront of a revolution, where “mainstream internet users were optimistic about its benefits, particularly the future of e-commerce.” Nasdaq, notably, “became the first US stock market to trade online,” perfectly symbolizing this new, fast-paced digital economy.

This persona thrived on rapid growth, speculative investments, and the promise of disruptive innovation. The context mentions that “the dot-com bubble of 1997–2000 brought wealth to some entrepreneurs before its crash of the early-2000s,” capturing the essence of this high-stakes, high-reward era. Companies with often flimsy business models but catchy ‘.com’ names commanded astronomical valuations, attracting capital in what seemed like an endless flow. It was a ‘macho’ pursuit of rapid expansion, often prioritizing market share and user acquisition over sustainable profitability, fueled by a belief that the internet would change everything overnight.

The “proliferation of new media such as the internet” empowered these entrepreneurs, allowing them “to self-publish web pages and make connections on professional, political and hobby topics,” fostering a sense of democratized innovation. While the “digital divide was immediate,” limiting initial access, the underlying optimism was infectious. This era celebrated the maverick, the individual who could spot the next big thing and ride the wave of digital transformation to unimaginable riches, with little emphasis on established rules or cautious forecasting.

However, the ‘Dot-Com Bubble Entrepreneur Persona,’ with its emphasis on unbridled speculation and growth at all costs, would dramatically flop in today’s more mature and scrutinizing tech landscape. The lessons learned from the early 2000s crash have instilled a greater demand for robust business models, ethical practices, and long-term sustainability. Investors and the public are far warier of hype, looking for tangible value and responsible innovation rather than just soaring valuations.

Modern entrepreneurs face intense scrutiny regarding data privacy, user well-being, and the broader societal impact of their platforms. The era of ‘move fast and break things’ has given way to a call for accountability and a more conscious approach to technology development. Today’s successful tech leaders must demonstrate not just innovation, but also social responsibility, transparency, and a commitment to bridging the “digital divide” rather than just exploiting new markets, making the ’90s-style, purely profit-driven, speculative approach seem remarkably out of step.

Read more about: Nostalgic for the Nineties? Relive the Pivotal Moments, Tech Booms, and Global Shifts That Defined a Decade

8. **The Technological Frontier Conqueror Persona**The 1990s was a decade characterized by a relentless march of scientific and technological progress, fostering what we identify as the ‘Technological Frontier Conqueror Persona.’ This mindset embodied an almost boundless optimism about humanity’s ability to master nature and revolutionize daily life through scientific innovation. The sheer volume of breakthroughs was staggering, from the “World Wide Web” gaining “massive popularity worldwide” to the “evolution of the Pentium microprocessor,” setting the stage for personal computing dominance.

This persona celebrated advancements that promised to reshape industries and human understanding. Major scientific endeavors like “The Human Genome Project, launched in 1990,” aimed “to sequence the entire human genome,” signaling humanity’s ambition to unlock the very code of life. Similarly, the commencement of “Building the Large Hadron Collider… in 1998” highlighted an audacious drive to explore the fundamental particles of the universe. Even in entertainment, “Video game popularity exploded due to the development of CD-ROM supported 3D computer graphics on platforms such as Sony PlayStation, Nintendo 64, and PCs,” showcasing technological mastery for leisure.

Such was the pace and scale of innovation that it cultivated a ‘macho’ belief in technology as an unalloyed good, an unstoppable force that would inevitably solve humanity’s problems and push the boundaries of what was possible. The invention of “rechargeable lithium-ion batteries” and the “first gene therapy trial” further underscored this narrative of constant forward momentum and the conquest of perceived limitations. This was an era where the risks and ethical implications, while perhaps considered by some, often took a backseat to the excitement of discovery and development.

However, this ‘Technological Frontier Conqueror Persona’ would find itself severely challenged and potentially rejected in the contemporary world. The uncritical optimism of the 1990s has given way to a more cautious and ethically informed perspective. We now grapple with the profound societal implications of rapid technological change, from concerns over data privacy, the spread of misinformation (amplified by the very internet celebrated in the ’90s), to the ethical dilemmas posed by advancements like AI and genetic engineering.

The context’s subtle mention of “environmentalism divided between left-wing green politics, primary industry-sponsored environmentalist front organizations, and a more business-oriented approach” in the ’90s points to a nascent awareness that has since exploded into mainstream consciousness. Today, the environmental footprint of technology is a critical concern, and any ‘conqueror’ mentality that overlooks sustainability or social equity, particularly regarding the “digital divide,” would be met with widespread skepticism. Modern tech leadership requires a deep sense of responsibility and a collaborative spirit, rather than the singular, often hubristic, drive to merely push boundaries.

9. **The Media Spectacle Politician Persona**The 1990s, with its burgeoning cable television and the early days of the internet, fostered the ‘Media Spectacle Politician Persona’—a figure adept at navigating an increasingly sensationalized media landscape. While “traditional mass media continued to perform strongly,” the “advance of alternative media” began to hint at a more fragmented, yet equally voracious, public appetite for news and political drama. This was a time when politicians were increasingly judged not just on policy, but on their ability to perform under intense public scrutiny and manage perception in a rapidly evolving media environment.

Perhaps the most iconic example of this persona’s challenge and endurance was the “Lewinsky scandal,” which caught “US president Bill Clinton in a media-frenzied scandal” in 1998. The sheer volume of media coverage and public discourse surrounding this event highlighted how political figures were forced to become central characters in ongoing national dramas. Despite the “United States House of Representatives impeached Bill Clinton… for perjury under oath,” he was ultimately acquitted by the Senate, serving out his term. This demonstrated a certain resilience possible within the ’90s media framework, where a seasoned politician could weather even the most intense storms.

This persona often involved a carefully curated public image, an ability to charm or deflect, and a reliance on established media gatekeepers to control narratives. Even global figures like “Nelson Mandela voting in 1994” were presented through powerful media imagery, shaping public perception on a grand scale. The humor of the decade, “marked by ironic self-references mixed with popular culture references” in television and film, reflected a societal shift towards a more self-aware, mediated existence, which politicians had to adapt to.

However, the ‘Media Spectacle Politician Persona’ of the 1990s would be woefully unprepared for today’s hyper-connected, real-time media ecosystem. The control over narrative that politicians once exerted, even during scandals, has largely evaporated. Social media, citizen journalism, and the 24/7 news cycle mean that every action, every statement, and every perceived misstep is immediately amplified, dissected, and often weaponized across global platforms.

In the ’90s, “the internet provided anonymity for individuals skeptical of the government,” but today, that skepticism is amplified and organized through networked communities, making it far harder to manage a crisis behind closed doors or through carefully worded press releases. The public now demands authenticity and direct engagement, and any attempt by a politician to rely on the ’90s model of a managed media spectacle would likely be perceived as inauthentic, manipulative, and quickly unravel under the relentless glare of modern digital scrutiny, rendering such a persona obsolete.

Read more about: From Honda to Hypercars: A Deep Dive into Jeff Bezos’ $20 Million Garage and His Eclectic Automotive Passions

10. **The Regional Power Assertor Persona**Amidst the larger narratives of globalization and technological progress in the 1990s, there persisted a tenacious ‘Regional Power Assertor Persona,’ characterized by the willingness of states or factions to aggressively pursue territorial, economic, or ethnic claims within their immediate spheres of influence. This often manifested in overt military action or intense diplomatic pressure, reflecting a ‘macho’ assertion of dominance in localized contexts. The post-Cold War vacuum, in some areas, allowed these regional ambitions to flourish without immediate, overwhelming global consensus for restraint.

Numerous conflicts across the decade exemplify this persona. Iraq’s “invasion and conquered Kuwait” in 1990, driven by accusations of oil market manipulation, clearly demonstrates a regional power acting aggressively on economic pretexts. Similarly, “The Eritrean–Ethiopian War (1998–2000) was commenced by the invasion of Ethiopia by Eritrea due to a territorial dispute.” The “Yugoslav Wars (1991–1995)” were notorious for “ethnic cleansing and genocide,” directly stemming from “ethnic tensions and violence… creating a greater sense of ethnic identity among nations in newly independent countries and a marked increase in the popularity of nationalism.” These were fierce assertions of identity and power on a regional scale.

Even in other parts of the former Soviet bloc, regional powers asserted themselves forcefully, such as “The First Chechen War (1994–1996)” between the Russian Federation and the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria. Later in the decade, “The Kargil War (1999) began… when Pakistan covertly sent troops to occupy strategic peaks in Kashmir,” a direct, aggressive territorial claim against India. These events showcase a willingness to employ military might to achieve regional objectives, often with a calculated risk of international backlash, which in the ’90s, might not have been as immediate or decisive as it is today.

However, this ‘Regional Power Assertor Persona’ would face an entirely different and far more formidable global response in the 21st century. The lessons learned from the humanitarian catastrophes of the 1990s, such as the “Rwandan genocide” where the “United Nations and major states came under criticism for failing to stop,” have significantly heightened global sensitivity to human rights violations and aggressive territorial expansion. This now translates into swifter, more coordinated international condemnation, economic sanctions, and often, more decisive multilateral interventions.

Today’s interconnected world, amplified by instant global communication through the internet and “advance of alternative media,” means that regional aggressions are immediately visible to billions, creating immense pressure for international action. Furthermore, the economic interdependencies of globalization make aggressive regional actions far more costly, as exemplified by the “political fiasco for Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif” following the Kargil War. The ‘macho’ display of regional military might, once a viable, albeit brutal, strategy for some ’90s leaders, is now largely unsustainable, with a greater emphasis on diplomacy, multilateralism, and adherence to international law being expected from even regional actors.

As we close the book on these ten ‘macho personas’ from the 1990s, it’s abundantly clear that the global stage has undergone a seismic transformation. The confidence of the sole superpower, the unbridled ambition of early tech moguls, the uncritical faith in scientific progress, the carefully managed political spectacle, and the raw assertion of regional power—all hallmarks of the Nineties—would simply not translate effectively into our current reality. The subtle shifts and emerging trends of that decade, from the “advance of alternative media” to the nascent “rise of anti-Western sentiment” and growing awareness of “multiculturalism,” have blossomed into defining forces of the 21st century. Today’s world demands nuanced understanding, collaborative leadership, ethical consideration, and an accountability that the ’90s, for all its dynamism, often overlooked. These personas, once dominant, now stand as fascinating relics, powerful reminders of how quickly the world can change, rendering even the most formidable attitudes of yesterday utterly irrelevant today.”

, “_words_section2”: “1945