Marshall Brickman, a prolific and versatile writer whose career spanned award-winning screenplays, groundbreaking Broadway musicals, and seminal moments in late-night television comedy, died on Friday in Manhattan. He was 85. His daughter Sophie Brickman confirmed his death, though a cause was not cited.

Mr. Brickman’s profound impact on American culture is perhaps most vividly remembered through his collaborations with Woody Allen, particularly their Oscar-winning script for “Annie Hall.” Yet, his creative footprint extended far beyond, encompassing the book for the enduring Broadway hit “Jersey Boys,” his foundational work as a head writer for Johnny Carson’s “The Tonight Show,” and a lesser-known but equally fascinating career as a folk musician.

His diverse talents allowed him to navigate different facets of the entertainment industry with a singular wit and an innate understanding of narrative and humor. From the philosophical musings of urban neurotics to the gritty backstory of a 1960s rock group, Mr. Brickman brought depth, precision, and an unmistakable voice to every project he touched, leaving behind a legacy marked by both critical acclaim and popular success.

1. **The Oscar-Winning Collaboration with Woody Allen on “Annie Hall”**Marshall Brickman’s name became synonymous with a particular brand of sophisticated, neurotic comedy through his collaborations with Woody Allen, most notably their Academy Award-winning screenplay for “Annie Hall” (1977). This film, an unconventional romance about urban neurotics, broke new ground with its loosely structured narrative and blend of intellectual wit and cultural references. It began as a story of a man turning 40, trying to gain perspective on his life, and originally did not even feature the character of Annie.

Mr. Brickman is credited with suggesting the creation of a character opposite to Allen’s persona to build dramatic tension, specifically writing with Diane Keaton in mind. This creative decision led to one of film history’s most endearing and iconic characters. The film, opening in April 1977, garnered widespread critical acclaim and went on to secure four Academy Awards: Best Picture, Best Actress for Diane Keaton, Best Director for Mr. Allen, and Best Original Screenplay for both Mr. Brickman and Mr. Allen.

Mr. Allen, notoriously disdainful of award ceremonies, did not attend, leaving Mr. Brickman to accept their shared Oscar. In his acceptance speech, Mr. Brickman acknowledged Mr. Allen’s indispensable contribution, stating, “Half of this little piece of tin, if not much more, belongs to Woody, who is probably the greatest collaborator anyone could ever wish for.” He humorously added that Mr. Allen also “picks up my lunch check for about five months, and [today] he refuses to come out of his apartment.” Mr. Brickman also referenced one of the film’s oft-quoted lines, saying, “I’ve been out here a week, and I still have guilt when I make a right turn on a red light.”

Beyond its accolades, “Annie Hall” was celebrated for its intellectual depth and its ability to capture a specific cultural moment. Mr. Brickman told Vanity Fair in 2017, “If the film is worth anything, it gives a very particular specific image of what it was like to be alive in New York at that time in that particular social-economic stratum.” Roger Ebert, in a 2002 appreciation, noted that “‘Annie Hall’ contains more intellectual wit and cultural references than any other movie ever to win the Oscar for best picture,” cementing its place as a cinematic benchmark.

Read more about: Tony Roberts, Urbane Stage and Screen Veteran, Dies at 85: A Life Defined by Versatility and Woody Allen Collaborations

2. **The Foundational Partnership: “Sleeper” and “Manhattan”**The creative synergy between Marshall Brickman and Woody Allen extended beyond “Annie Hall” to form a significant body of work that defined an era of sophisticated American comedy. Their partnership began with the 1973 film “Sleeper,” a science fiction comedy set in a totalitarian 22nd-century America. Originally conceived as an homage to silent comedy, with Mr. Allen initially intending to forgo dialogue, the film evolved to incorporate the neurotic, witty character that Mr. Allen had spent years developing, realizing that dialogue was essential to play to those strengths.

Vincent Canby, then the chief film critic of The New York Times, lauded “Sleeper,” comparing it to “the best of Laurel and Hardy,” and describing it as “charming — a very even work, with almost no thudding bad lines and with no low stretches.” This early success laid the groundwork for their subsequent projects. Mr. Allen and Mr. Brickman’s collaboration on “Sleeper” proved to be a pivotal moment, a “pleasure and a life changer,” as Mr. Brickman described it in a 2011 Writers Guild Foundation interview.

Following “Annie Hall,” the duo collaborated on “Manhattan” (1979), a black-and-white romantic comedy hailed as a “love letter to New York.” The film’s narrative explored the complexities of relationships, often featuring witty, pithy observations that became hallmarks of their joint screenplays. While the film has been remembered for its central, controversial relationship between a middle-aged man and a high school girl, it was initially widely acclaimed, winning BAFTAs for Best Film and Best Screenplay, and named Best Foreign Film at France’s César Awards.

Mr. Canby further observed Mr. Allen’s rapid progress as a filmmaker with “Manhattan,” noting, “Mr. Allen’s progress as one of our major filmmakers is proceeding so rapidly that we who watch him have to pause occasionally to catch our breath.” These early films established a distinctive comedic voice that blended intellectualism with everyday neuroses, a style that Marshall Brickman helped to refine and articulate, making him an indispensable partner in Mr. Allen’s most celebrated early works.

3. **A Lighter Touch: “Manhattan Murder Mystery” and Lifelong Friendship with Allen**While “Annie Hall,” “Sleeper,” and “Manhattan” solidified Marshall Brickman’s status as a formidable screenwriter, his later collaboration with Woody Allen on “Manhattan Murder Mystery” (1993) showcased a different facet of their creative relationship. This dark comedy, from an Allen-Brickman script that had been set aside decades earlier, marked a return to their collaborative efforts amidst significant changes in Mr. Allen’s personal life and film productions, including replacing Mia Farrow with Diane Keaton as the female lead. The film demonstrated their enduring ability to craft engaging narratives with a blend of humor and suspense, even under challenging circumstances.

The professional partnership between Mr. Brickman and Mr. Allen was underpinned by a deep and lasting personal friendship. They had first met in the early 1960s when Mr. Allen was an emerging stand-up comedian and Mr. Brickman was brought on to write jokes for him. Their shared background in New York, and a common understanding of its unique cultural neuroses, fueled their creative chemistry. As Mr. Brickman said in a 2011 interview with the Writers Guild, while Mr. Allen was the dominant voice in their writing, Mr. Brickman was undoubtedly a significant contributor, shaping the material with his unique perspective.

Mr. Allen himself recalled their collaborative process, describing days spent talking about scenes and characters while strolling around Central Park and the city, often concluding with dinner at Elaine’s. “I usually write alone,” Mr. Allen stated. “I’ve done 50 movies, almost all of them alone. So working with him was not so lonely.” This intimate, conversational approach highlights the depth of their rapport, which transcended mere professional collaboration to become a bond of mutual respect and creative camaraderie.

Even with the film’s original title, “Anhedonia” — meaning the inability to feel pleasure — being rejected by the distributor, United Artists, Mr. Allen recalled the “manic euphoria” they felt when devising it, showcasing a shared sense of humor and intellectual playfulness. Mr. Allen praised Mr. Brickman’s unique comedic talent, saying, “There are many people making a living from comedy, but really authentically funny people, there aren’t a lot of them. I felt Marshall was an authentically funny person — a wonderful wit.” Their lifelong friendship and working relationship stands as a testament to Mr. Brickman’s enduring impact on Mr. Allen’s most cherished works.

4. **Crafting Comedy Gold for Johnny Carson: Carnac the Magnificent**Before his illustrious film career, Marshall Brickman had already made an indelible mark on American television comedy, most notably as head writer for Johnny Carson’s “The Tonight Show.” His tenure in the late 1960s was a period of creative ferment that yielded some of the show’s most beloved and enduring sketches. Mr. Brickman joined the show when Dick Cavett, then another up-and-coming joke writer, helped him get in the door. When head writer Walter Kempley quit over a salary dispute, Mr. Brickman stepped into the role.

One of Mr. Brickman’s most enduring contributions to pop culture from this period was the creation of “Carnac the Magnificent.” This recurring sketch featured Johnny Carson donning a black cape and a bejeweled wine-red turban, holding a sealed envelope to his forehead, and appearing to intuit the contents. The segment was a masterclass in comedic timing and inverse punchlines, with Carson divining the answer before revealing the question. Examples included, “‘A budget cut,’ he might say. Then he’d open the envelope and clarify: ‘What do you get from a discount rabbi?’” or “‘The winners,’ followed by ‘Who are the Dodgers playing tonight?’”

Mr. Brickman confessed to inventing what he called the “Carnac Saver,” a follow-up joke designed to salvage laughs when an initial punchline fell flat. He claimed to have “invented the Carnac Saver” to prevent comedic failures. Examples included, “May your Perrier water be secretly bottled in Tijuana” and “May a love-starved fruit fly molest your sister’s nectarines.” This ingenious device underscored his deep understanding of comedic mechanics and his dedication to ensuring the success of the material, even going to his grave apologizing for it, according to an interview for Mike Sacks’ 2009 book, *And Here’s the Kicker*.

Despite the significant workload associated with being head writer — which included writing “five spots” like Aunt Blabby, Carnac, and Tea Time Movies — Mr. Brickman described the experience as “great, it was absolutely great.” His time on “The Tonight Show” demonstrated his exceptional talent for crafting accessible yet sophisticated humor that resonated with a mass audience, establishing a foundation for the wide-ranging career that followed. This period showcased his ability to develop iconic characters and comedic structures that remain celebrated decades later.

5. **The Unexpected Musical Beginnings: The Tarriers and “Dueling Banjos”**Long before he became an Oscar-winning screenwriter, Marshall Brickman nurtured a passion for music, particularly the banjo, which led him down an unexpected path in his early career. After graduating from the University of Wisconsin with degrees in science and music, he initially considered a career as a doctor but changed his mind after a semester assisting a pathologist. Music became a serious career option, and he joined the folk group The Tarriers in 1962, replacing Alan Arkin, who left to pursue improv comedy and acting.

The Tarriers had previously scored a hit with “Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)” when Mr. Arkin was a member. Mr. Brickman joined the group not just for his musical talent, but also because, as he told the Writers Guild in 2011, “One of the reasons I was asked to join was because they needed somebody to front the group and talk while everybody was tuning up.” This informal role allowed him to begin developing the comedic bits and routines that would later define his writing career.

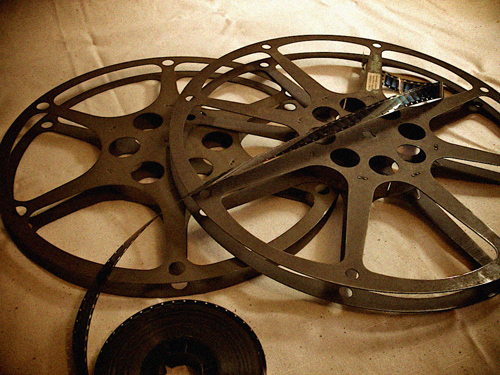

In a fascinating twist of fate, an album Mr. Brickman recorded years earlier with his college roommate Eric Weissberg, titled “New Dimensions in Banjo and Bluegrass,” was unexpectedly chosen as the soundtrack for the 1972 Burt Reynolds film “Deliverance.” This album included the now-iconic track “Dueling Banjos.” Mr. Brickman humorously recounted how his accountant called him with a check for $170,000 from Warner Bros., leaving him bewildered as he had no idea why. Warner Bros. had taken their old Elektra label album and renamed it the soundtrack from “Deliverance,” selling over a million units, a testament to the album’s unexpected popularity.

Mr. Brickman also briefly played banjo as a member of The New Journeymen in 1964, a trio that included John Phillips and Michelle Phillips. When Mr. Brickman left the group, the couple brought in two new partners, subsequently forming The Mamas & the Papas, a band that would go on to achieve immense fame. This early musical journey not only provided him with a living but also served as an unwitting training ground for his comedic instincts and narrative development, proving that fortune indeed favors not just the prepared, but sometimes the lucky.

6. **Solo Directorial Ventures: “Simon,” “Lovesick,” and “The Manhattan Project”**While Marshall Brickman is widely celebrated for his screenwriting partnerships, he also ventured into directing films on his own, showcasing his unique comedic voice and narrative interests. His directorial debut was the 1980 film “Simon,” a quirky comedy starring Alan Arkin as a psychology professor who is brainwashed into believing he is from outer space. The film explored themes of identity and perception through a distinctly offbeat lens, reflecting Mr. Brickman’s penchant for clever, intellectual humor.

He followed “Simon” with “Lovesick” in 1983, a romantic comedy that featured Dudley Moore as a psychiatrist who falls in love with one of his patients, Elizabeth McGovern. Adding a surreal touch, Alec Guinness appeared as the ghost of Sigmund Freud, offering relationship advice to the protagonist. This film further demonstrated Mr. Brickman’s willingness to blend comedic situations with fantastical elements, pushing the boundaries of conventional storytelling while maintaining an engaging narrative.

His third directorial effort, “The Manhattan Project” (1986), took a more satirical and darkly comedic approach. The film centered on a high school student who, for a science fair project, successfully builds a nuclear weapon. This ambitious premise allowed Mr. Brickman to explore complex social and political themes through the accessible framework of a teen drama, highlighting his versatility as a storyteller. He also served as writer or co-writer on all three of these films, demonstrating his comprehensive creative control over these projects.

These films, while not achieving the widespread recognition of his collaborations with Woody Allen or his Broadway successes, were important showcases for Mr. Brickman’s independent vision as a filmmaker. They solidified his reputation as a director capable of crafting comedies that were both intellectually stimulating and entertaining, contributing to a diverse and expansive career that defied easy categorization.

7. **The Broadway Triumph: “Jersey Boys” and a New Stage**Marshall Brickman’s remarkable career took a significant turn toward the stage, culminating in the monumental success of the Broadway musical “Jersey Boys.” Teaming with Rick Elice, Mr. Brickman penned the book for this acclaimed production, which chronicled the rise of the iconic 1960s rock group The Four Seasons. Initially, Mr. Brickman was not immediately drawn to the project, but a deeper dive into the group’s origins proved compelling.

His interest was piqued upon discovering the gritty back story of The Four Seasons, rooted in Newark neighborhoods where, as he noted, “the Mafia was just another bit of local color.” This human element, combined with the “brink-of-manhood perspective” evident in their hit songs, resonated with his storytelling sensibilities. Mr. Brickman observed that “the songs the Four Seasons did were guys singing to each other about girls,” highlighting the raw authenticity he sought to capture.

His academic background, particularly his degree in music from the University of Wisconsin, proved invaluable in this new endeavor. Collaborating with composers, Mr. Brickman found his musical understanding facilitated a seamless creative process. “It allows me to talk to composers in their own language,” he stated, adding, “I understand how to achieve certain effects harmonically. There’s no decoding necessary.” This unique advantage allowed him to contribute profoundly to the musical’s structure and emotional resonance.

“Jersey Boys” premiered in November 2005 and became a sensation, running on Broadway for an extraordinary 12 years. The production garnered widespread critical acclaim and popular adoration, securing four Tony Awards, including the coveted prize for Best Musical. Although the book for the musical, co-written by Mr. Brickman and Mr. Elice, was nominated but ultimately lost to “The Drowsy Chaperone,” its enduring appeal led to a 2014 film adaptation, for which Mr. Brickman and Mr. Elice also wrote the screenplay, marking Mr. Brickman’s last film script.

8. **Expanding Horizons: “The Addams Family” and Stagecraft Philosophy**Following the unqualified success of “Jersey Boys,” Marshall Brickman continued his collaborative foray into musical theater with Rick Elice, contributing to the book for “The Addams Family” in 2010. This production brought the beloved, ghoulish characters created by Charles Addams and popularized by the television show to the Broadway stage. The musical, which starred Nathan Lane and Bebe Neuwirth in lead roles, embarked on a 20-month run at the Lunt-Fontanne Theater.

While “The Addams Family” did not achieve the same colossal, enduring success as “Jersey Boys,” it further demonstrated Mr. Brickman’s versatility and his capacity to adapt diverse source material for the demanding live stage. His work on this musical showcased his adeptness at translating established characters and their distinctive humor into a new format, a testament to his wide-ranging creative abilities. The transition from film to theater presented distinct challenges, as he noted.

Mr. Brickman reflected on the technical intricacies inherent in stage productions, contrasting them with the flexibility of filmmaking. He explained to The Greenville (S.C.) News in 2013 that “Broadway is much more complicated technically, in a way, than film because on film you can stop and go back and do it again.” This observation underscores his deep understanding of the unique demands and craft required for each medium, navigating the live, unforgiving nature of theater with his characteristic precision.

His contributions to Broadway solidified his reputation as a writer who could seamlessly transition between different forms of entertainment, from late-night television sketches and Oscar-winning screenplays to successful musical theater productions. His work with “The Addams Family” reinforced his position as a multifaceted storyteller whose creative reach knew few bounds, always bringing his distinctive wit and narrative intelligence to each project.

9. **Formative Television: “Candid Camera,” “The Dick Cavett Show,” and “The Muppet Show”**Before his acclaimed tenure as head writer for Johnny Carson’s “The Tonight Show” and his celebrated film collaborations, Marshall Brickman honed his comedic and narrative skills in the burgeoning world of television. His earliest known writing credit dates back to 1960, when he joined the first season of CBS’s “Candid Camera.” This pioneering “pre-reality-show reality show,” as it has been described, offered Mr. Brickman an early platform to develop his keen observational humor.

Mr. Brickman recounted that securing a position on “Candid Camera” was relatively straightforward due to the demanding nature of its creator-producer, Allen Funt, whom few could tolerate for long. It was during this period that Mr. Brickman shared an office with other future comedic luminaries like Fannie Flagg and Joan Rivers, an environment that undoubtedly fueled his comedic development. Interestingly, Woody Allen also wrote for and appeared in segments of the program, foreshadowing their future collaborations.

After his influential years at “The Tonight Show,” Mr. Brickman transitioned to “The Dick Cavett Show” in the early 1970s, taking on the role of creative consultant and producer. This move reunited him with Dick Cavett, a former “Tonight Show” writer who had helped Mr. Brickman get his start there. This period allowed him to explore different facets of late-night talk, contributing to a more intellectual and conversational style of comedy.

Further cementing his diverse television portfolio, Mr. Brickman was one of four writers for the 1975 television pilot, “The Muppet Show: Sex and Violence.” Conceived as a satire on what was perceived as the declining quality of television, this pilot, after substantial revisions, evolved into “The Muppet Show,” the beloved syndicated half-hour series created by Jim Henson. His involvement in this iconic program underscored his ability to contribute to a broad spectrum of comedic genres, from satirical sketches to family-friendly entertainment.

10. **The Writer’s Ethos: Philosophy on Collaboration and Craft**Marshall Brickman often articulated a clear and insightful philosophy regarding the art of writing and, particularly, the dynamics of creative collaboration. He maintained a strong belief that for any partnership to thrive, a singular vision must ultimately guide the project. “I don’t think there’s any such thing really as an equal collaboration,” Mr. Brickman told the Writers Guild, explaining, “I think that in any collaboration, one person, one personality, one point of view has to dominate.”

This perspective was especially evident in his work with Woody Allen, where Mr. Brickman readily acknowledged Mr. Allen as the dominant creative force. He clarified, however, that this did not diminish his own significant contributions. He pointed out that Mr. Allen was inherently writing for himself as an actor and director, making him the natural choice to steer the material. Mr. Brickman also suggested that writing often involves a deeply personal, almost therapeutic process, where one seeks to “work something out” through the narrative.

Working alongside Mr. Allen, Mr. Brickman found a unique professional intimacy that transcended typical collaboration. Mr. Allen himself remarked on this, stating, “I usually write alone. I’ve done 50 movies, almost all of them alone. So working with him was not so lonely.” Their collaborative process involved long days of conversation, strolling through Central Park, discussing scenes and characters, often concluding with dinner, a testament to their deep friendship and shared intellectual life.

Mr. Brickman’s insights extended to the practicalities and personal choices shaping a career in entertainment. Despite his success, he admitted to never having a grand “career master plan,” humorously remarking to The New York Times in 1986 that some early decisions were “based on how late I could sleep in the morning.” He also reflected on the interplay of preparation and fortune, stating, “It’s important to be lucky,” even while believing “fortune favored the well prepared,” encapsulating his humble yet profound understanding of his own journey.

11. **Formative Years: From Rio to Brooklyn and the Roots of a Creative Mind**Marshall Brickman’s life began far from the bustling artistic centers of New York, born on August 25, 1939, in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. His parents, Abram and Pauline Brickman, were devoted Jewish socialists; his father had fled Poland during World War II, and his mother hailed from the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Their time in Brazil was tied to Abram Brickman’s work in the import-export business, but the family soon relocated to the United States in 1943, settling in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn.

It was in Brooklyn that Mr. Brickman spent his formative years, growing up in an environment where music was not just appreciated but actively emphasized by his parents. Sundays often saw the Brickman family attending folk festivals in Washington Square Park, fostering a deep connection to music that led him to learn the banjo, guitar, and mandolin. This early immersion in musical culture laid a foundational layer for his later, unexpected musical career, as well as influencing his comedic timing and narrative sensibilities.

His academic journey initially pointed towards a career in medicine. After graduating from Brooklyn Technical High School, Mr. Brickman enrolled at the University of Wisconsin with aspirations of becoming a doctor. However, a semester assisting a pathologist at Wisconsin General Hospital led him to a pivotal change of heart. He subsequently shifted his major to music, acquiring two degrees that, in his characteristic wit, he once described as “two worthless pieces of paper instead of one.”

Despite the self-deprecating humor, his diverse educational background in science and music proved instrumental in his eclectic career. The cultural milieu of his Brooklyn upbringing, infused with his parents’ socialist ideals and the vibrant New York-Jewish humor, undeniably shaped his perspective. This background was a shared thread with Woody Allen, contributing to the distinct “humor and neuroses signature to New York-Jewish culture” that became a hallmark of their collaborative screenplays, particularly “Annie Hall.”

12. **The Broad Strokes of a Lasting Legacy**Marshall Brickman’s death at 85 marked the end of a career that was as varied as it was impactful, leaving an indelible mark across multiple facets of American entertainment. Beyond the iconic films, the beloved television sketches, and the award-winning Broadway musicals, his legacy is defined by a unique blend of intellectual rigor, accessible humor, and an unwavering commitment to the craft of storytelling. He was honored by the Writers Guild in 2006, a testament to the respect he commanded from his peers.

His diverse talents allowed him to navigate different facets of the entertainment industry with a singular wit and an innate understanding of narrative and humor. From the philosophical musings of urban neurotics to the gritty backstory of a 1960s rock group, Mr. Brickman brought depth, precision, and an unmistakable voice to every project he touched. Even in his later career, he continued to explore new avenues, directing the 2001 Showtime movie “Sister Mary Explains It All,” an adaptation starring Diane Keaton, showcasing his continued range and adaptability.

Mr. Brickman often shared insights into his approach to his craft, embodying a professional ethos that valued both integrity and adaptability. He once told Variety that while he had few regrets, he made choices based on “who I don’t mind having lunch with,” highlighting a preference for congenial partnerships over purely strategic career moves. This personal philosophy underpinned his long-standing and creatively fruitful relationships, most notably with Woody Allen.

Read more about: Unlock the Power of Nine: Practical Insights into a Pervasive Number

His passing is mourned by his family, including his wife, Nina Feinberg, whom he married in 1973 and who also worked as a film editor and producer; his daughters Sophie and Jessica; and five grandchildren. Marshall Brickman’s life stands as a testament to a career shaped not by a rigid master plan, but by a curious mind, a versatile talent, and an openness to serendipitous opportunities, leaving behind a body of work that continues to entertain and resonate with audiences worldwide.