In the grand tapestry of human existence, there are threads so ancient, so intricate, that they can only be traced by those with the dedication to unearth them. Imagine civilizations rising and falling, stories untold, technologies forged, and beliefs held, all buried beneath the dust of millennia. This is the realm of archaeology—a discipline that doesn’t just study history, but actively *reconstructs* it, bringing to life the silent narratives of our collective past and, sometimes, challenging everything we thought we knew about human origins. The promise of newly unearthed civilizations isn’t just a thrilling headline; it’s a testament to the ongoing power of this vital science. It holds the potential to add entirely new chapters to humanity’s story, forcing us to re-evaluate our timelines, our migrations, and our very understanding of how societies evolve.

Archaeology is more than just digging up old bones and pottery; it’s a profound journey into the heart of what it means to be human. It’s a quest that provides invaluable insights into the past, helping us understand the development, diversity, and interconnectedness of human societies across vast spans of time. Through meticulous investigation and passionate interpretation, archaeologists piece together the fragments of vanished worlds, tracing the origins of civilizations, unraveling historical mysteries, and ultimately enriching our comprehension of human achievement and struggle. Their work offers a unique window into cultures that left no written records, or whose records were biased or incomplete, providing a balanced perspective that written history alone cannot achieve.

We are about to embark on an incredible journey, exploring the fascinating world of archaeology. From its fundamental definition to the diverse duties of its practitioners, the intricacies of fieldwork and analysis, the critical role of cultural heritage preservation, and the vast chronological framework that underpins all archaeological inquiry, we will delve into the very essence of how we come to know the people and societies who walked this earth long before us. Prepare to be amazed by the dedication, science, and sheer wonder involved in rewriting human origins, one artifact at a time.

1. Archaeology: Unearthing the Human Story

At its core, archaeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. This encompasses a vast array of evidence, including artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscapes. It is a discipline that uniquely straddles the realms of both a social science and a branch of the humanities, drawing on rigorous scientific methods while also delving into the nuanced cultural contexts of human experience. This dual nature allows for a comprehensive understanding of past societies, blending empirical data with interpretive insights.

Archaeology is particularly important for learning about prehistoric societies—those cultures that, by definition, did not make use of writing. This constitutes over 99% of the human past, stretching from the Paleolithic era until the advent of literacy in societies around the world. Without the diligent work of archaeologists, little or nothing would be known about the use of material culture by humanity that predates written records, leaving vast stretches of our collective story utterly blank. It is through these material remains that we can trace the fundamental developments that shaped early humanity.

The goals of archaeology are broad and deeply significant, ranging from understanding culture history to meticulously reconstructing past lifeways, and documenting and explaining changes in human societies through time. The scope of archaeological inquiry is immense, investigating human prehistory and history from the development of the first stone tools at Lomekwi in East Africa 3.3 million years ago, right up until recent decades. Crucially, archaeology is distinct from palaeontology, which focuses on the study of fossil remains of ancient life, whereas archaeology specifically investigates human activity and its material traces.

2. The Archaeologist’s Calling: Core Duties and Responsibilities

The duties and responsibilities of archaeologists are as diverse as the past itself, often varying depending on their specific area of expertise, the nature of the project or site they are working on, and the overarching goals of their research. However, universally, archaeologists provide invaluable insights into the past, helping us understand the development, diversity, and interconnectedness of human societies. Their tireless work helps us trace the origins of civilizations, unravel historical mysteries, and meticulously piece together the narratives of our collective human heritage. It’s a role that demands both intellectual rigor and immense practical skill.

In general, archaeologists engage in a broad spectrum of activities. This includes extensive fieldwork, where they survey, excavate, and document archaeological sites with painstaking precision. Back in the lab, they perform artifact analysis, meticulously examining recovered objects. Beyond individual artifacts, they undertake data interpretation, synthesizing vast amounts of information to reconstruct past societies. Essential to the academic fabric of the discipline, they also conduct significant research and contribute to scholarly publication, sharing their findings with the wider academic community and the public.

Furthermore, many archaeologists play a crucial role in cultural resource management, assessing the impact of modern development on historical sites. Collaboration and outreach are also key components of their work, as they frequently partner with colleagues from related fields, specialists, and local communities, engaging the public through lectures and exhibits. Underlying all these duties is a strong commitment to ethical considerations, ensuring respect for cultural heritage, responsible excavation, and the judicious dissemination of research findings. It is a profession built on careful observation, scientific analysis, and profound respect for the human story.

3. Into the Field: The Art and Science of Excavation

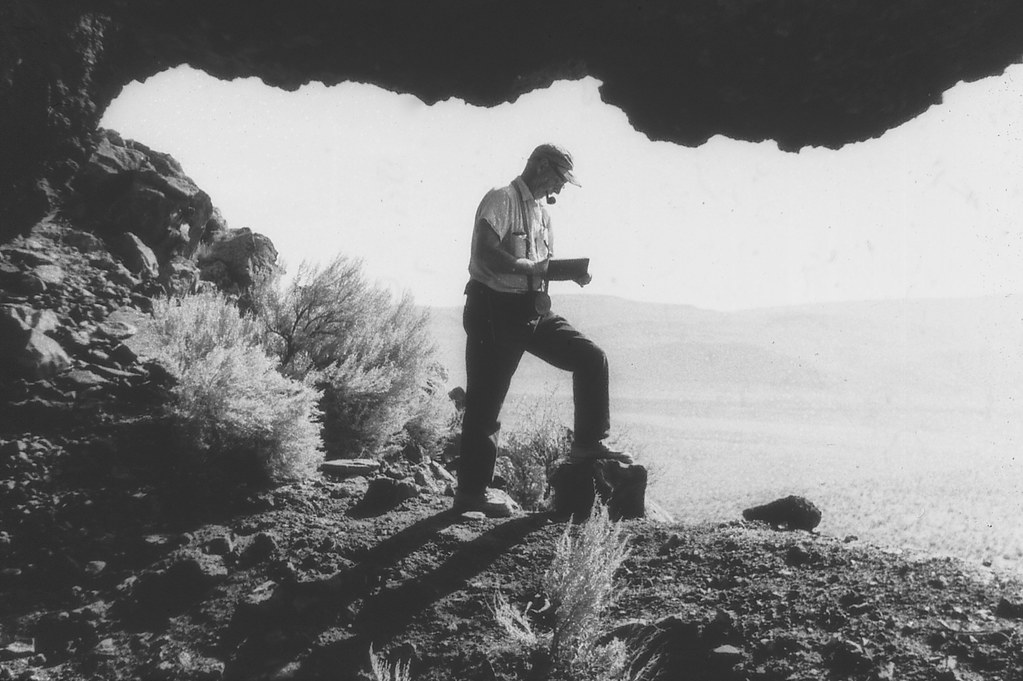

Fieldwork stands as a significant and often romanticized component of archaeological practice. It involves the direct engagement with archaeological sites through surveying, excavating, and documenting. Archaeologists deploy a variety of specialized tools and techniques to carefully unearth and recover artifacts, ecofacts (environmental remains), and architectural structures from the ground. This process is not merely about finding objects, but about ensuring the meticulous preservation of crucial contextual information, which is paramount to understanding the significance of any discovery. Every layer, every position, tells a part of the story.

A cornerstone of fieldwork is meticulous site recording and documentation. Archaeologists create detailed maps of sites, take numerous photographs from multiple angles, and maintain exhaustive notes on every aspect of the excavation. They pay particular attention to the stratigraphy—the layering of soil and artifacts—which is essential for understanding the chronology and context of the site. This precise record-keeping allows researchers to reconstruct the three-dimensional relationships between objects and features, providing the vital data needed to interpret human activities over time. Without this careful documentation, artifacts would lose much of their meaning.

The environment for fieldwork can be incredibly diverse, ranging from remote and rugged landscapes, often far from modern infrastructure, to urban areas undergoing rapid development. This demanding aspect of the work frequently requires considerable physical labor, including digging, sifting soil by hand, and carefully documenting and collecting fragile artifacts and ecofacts. Often, archaeologists work in close-knit teams, collaborating not only with fellow researchers and field technicians but also, increasingly, with local community members, whose traditional knowledge and participation can enrich the understanding of a site.

4. Unlocking the Past: Artifact Analysis and Data Interpretation

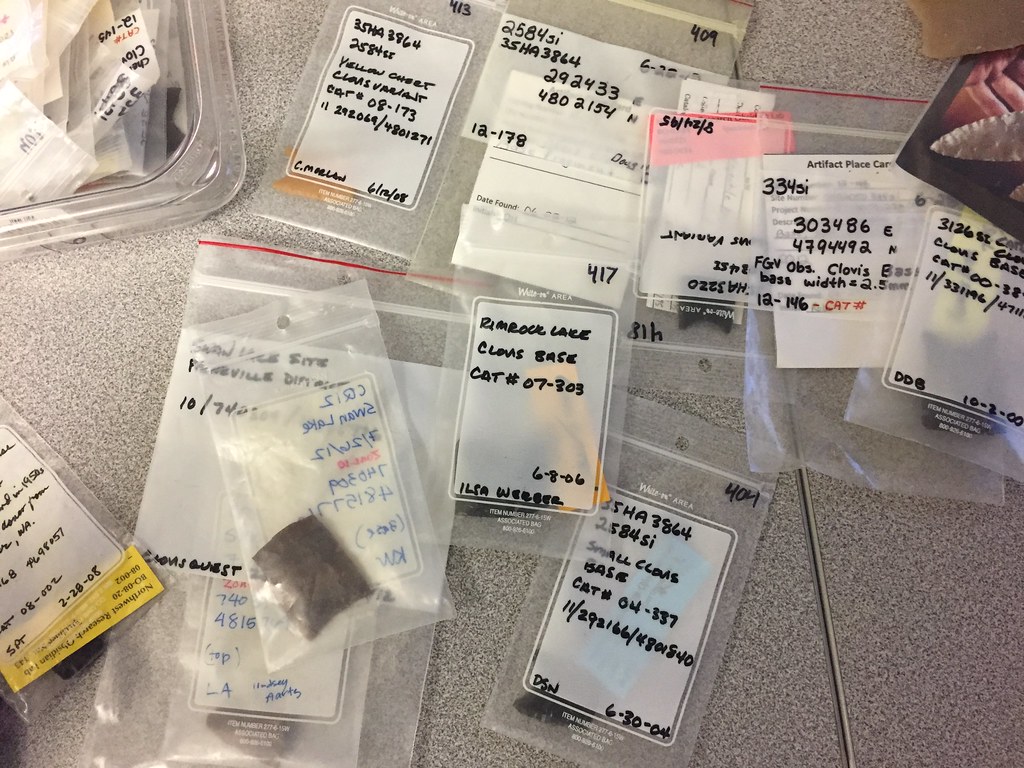

Once removed from their original context, the journey of archaeological finds continues into the laboratory, where artifact analysis commences. Here, archaeologists meticulously study the recovered objects, examining their materials, craftsmanship, and styles to glean insights into their functions, cultural significance, and the technological advancements of the people who created and used them. This intricate examination allows for a deeper understanding of daily life, ritual practices, and artistic expressions in past societies. Every chip, every wear pattern, holds a clue.

To further investigate artifacts and obtain additional information, archaeologists often conduct sophisticated laboratory analyses. These can include techniques such as radiocarbon dating, which provides chronological information by measuring the decay of radioactive isotopes in organic materials, or various forms of chemical analysis to determine the composition and origin of materials. Microscopic examination can reveal details about manufacturing techniques, diet, or environmental conditions, providing a wealth of information that is invisible to the naked eye. These scientific methods transform raw finds into data-rich evidence.

The ultimate goal of all this meticulous work is data interpretation, where archaeologists synthesize the vast amount of information they gather to reconstruct past societies. They analyze the spatial distribution of artifacts, architecture, and features to understand patterns of human behavior, settlement patterns, and economic networks, such as trade routes. They also seek to decipher social structures and belief systems. This interpretive phase often involves comparing their findings with historical documents, if available, or even oral traditions, to gain a broader and more nuanced understanding of the culture they are studying, weaving a coherent narrative from disparate pieces of evidence.

5. Stewards of the Past: Cultural Resource Management (CRM)

Cultural Resource Management (CRM) represents a crucial and increasingly prominent sector within archaeology, where practitioners work diligently in compliance with cultural resource management regulations. The primary function of CRM archaeologists is to assess the potential impact of proposed construction projects, infrastructure development, or land-use changes on archaeological sites and other cultural resources. This proactive approach ensures that the remnants of the past are not inadvertently destroyed by the march of progress, safeguarding irreplaceable heritage for future generations.

In this vital role, CRM archaeologists conduct systematic surveys of areas slated for development. These surveys are designed to identify significant archaeological sites, both known and previously undiscovered. Following identification, they make expert recommendations for their preservation or mitigation. Mitigation might involve careful excavation and detailed recording of a site before development proceeds, thus salvaging information that would otherwise be lost. Their work often involves navigating a complex interplay of legal requirements, development interests, and the inherent value of cultural heritage.

The contributions of CRM archaeologists are immense, ensuring the protection and preservation of cultural resources while simultaneously facilitating necessary development. They serve as a critical bridge between academic archaeology and the practical demands of modern society, emphasizing the ethical considerations central to the discipline—respecting cultural heritage, practicing responsible excavation and artifact preservation, and ensuring the responsible dissemination of research findings. It is a field that underscores the tangible value of the past in the face of ongoing change, embodying a commitment to responsible stewardship of the world’s ancient legacies.

6. Unpacking the Past’s Eras: The Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic Periods

Archaeologists commonly divide human history into distinct time periods, which serve as essential frameworks for study and analysis. While the specific divisions may exhibit slight variations depending on the geographical region or cultural context under examination, these chronological markers allow for a structured approach to understanding the immense sweep of human development. These periods help organize the vast amounts of material evidence recovered and interpreted, making sense of the long trajectory of human innovation and adaptation.

The earliest of these foundational periods is the Paleolithic, or Old Stone Age. This immense span encompasses the earliest known human history, distinguished by the characteristic use of rudimentary stone tools and the gradual development of early human species, the hominids. Extending from the very emergence of these early ancestors until the profound environmental shifts marking the end of the last Ice Age, roughly around 10,000 BCE, the Paleolithic witnessed fundamental advancements such as the evolution of humanity itself, the mastery of fire, and the initial creation of tools that defined our earliest interactions with the world.

Bridging the gap between the nomadic hunter-gatherer existence of the Paleolithic and the settled agricultural communities that followed is the Mesolithic, or Middle Stone Age. This transitional period, generally spanning from around 10,000 to 5,000 BCE, is characterized by the development of new, more refined tools, significant technological advancements, and evolving subsistence strategies. Humans adapted to post-glacial environments, developing specialized hunting and gathering techniques, and often utilizing smaller, more efficient stone tools known as microliths, reflecting a deeper understanding of their local ecosystems.

Following this is the Neolithic, or New Stone Age, a period marked by some of the most profound cultural and technological advancements in human history. Beginning typically around 8,000 BCE, it saw the revolutionary rise of agriculture, the domestication of animals, and the establishment of permanent settlements. This shift from mobile foraging to sedentary farming fundamentally reshaped human societies, leading to population growth, the development of villages, and new forms of social organization. The Neolithic typically concludes with the advent of metalworking, with dates varying regionally, generally between 2,000 to 4,000 BCE.

7. The Age of Metals: Bronze Age and Iron Age Societies

The transition from the Stone Ages ushered in a new era defined by metallurgical innovation, profoundly altering human technology and social organization. The Bronze Age, for example, is characterized by the widespread adoption and use of bronze—an alloy primarily of copper and tin—for crafting tools, weapons, and intricate ornaments. This period represents a significant shift from relying solely on stone, bone, and wood, as bronze offered superior hardness and durability. Dates for the Bronze Age vary across regions, generally spanning from around 3,300 to 1,200 BCE, and saw the rise of complex trade networks to acquire the necessary raw materials.

Building upon the foundations laid by the Bronze Age, the Iron Age is distinguished by the increasing use of iron for tools and weaponry, gradually replacing bronze. Iron, being more abundant than copper and tin, democratized access to strong metal tools and weapons, making them available to a broader segment of the population. This period is frequently associated with the emergence of even more complex societies, the formation of early states, and the rise of powerful empires, as agricultural output increased and military technologies advanced. The specific start and end dates of the Iron Age are regionally diverse, typically beginning around 1,200 BCE and continuing until the introduction of widespread written records in a given area.

These metal ages mark crucial milestones in human technological and societal evolution. The ability to extract, smelt, and work with metals not only led to more efficient tools for agriculture and construction but also revolutionized warfare and craftsmanship. The societal implications were immense, fostering new divisions of labor, specialized artisans, and increasingly stratified social structures. Through the study of the material remains from the Bronze and Iron Ages, archaeologists gain unparalleled insights into the economic systems, political organizations, and cultural identities of these transformative periods in human history.

8. Echoes of Empire: The Classical and Medieval Periods

Archaeology provides invaluable windows into periods marked by monumental shifts, specifically the Classical and Medieval eras. The Classical Period, spanning roughly from the 5th century BCE through the Roman Empire until 476 CE, showcased unparalleled cultural and intellectual contributions. Classical archaeologists meticulously investigate ancient Greece and Rome’s architecture, art, and material culture, excavating cities and analyzing inscriptions and pottery to reconstruct daily life and political structures. Their discoveries often corroborate or challenge classical texts, adding tangible dimensions to historical narratives.

Following this, the Medieval Period, or Middle Ages, spans from approximately the 5th to the 15th century CE. This era brought profound transformations in Europe, including the dissolution of the Western Roman Empire, the emergence of feudal systems, and the widespread dissemination of Christianity. Medieval archaeologists delve into the material remnants of this dynamic age, unearthing castles, monasteries, and fortified villages.

Their findings reveal intricate social hierarchies, evolving agricultural practices, and the daily struggles and beliefs of people during times of constant change. By preserving and interpreting this rich tapestry, medieval archaeology ensures a comprehensive understanding of post-Roman European development, enriching our knowledge of how societies adapted and rebuilt after imperial decline.

9. Modern Insights: Archaeology in the Recent Past

Beyond ancient worlds, archaeology extends its lens to the more recent past, offering insights into the origins of our modern society. The “Modern Period,” from the 15th century CE to the present, includes pivotal epochs like the Renaissance, Age of Exploration, and Industrial Revolution. Historical archaeologists reveal the tangible remnants of societies that shaped our current global landscape, providing crucial understanding of these transformations through material culture.

These specialists combine traditional archaeological methods with deep engagement in written records like ledgers, diaries, and maps. This dual approach offers a remarkably rich understanding of everyday life, social structures, trade networks, and interactions during rapid global change. They uncover stories often absent from official histories, providing ground-level perspectives on societal shifts.

By examining colonial settlements or early industrial complexes, historical archaeologists unearth objects speaking to class distinctions, evolving technologies, and individual experiences. This sub-discipline ensures a balanced perspective, bridging documentary evidence with lived realities, making recent history truly alive and highlighting tangible legacies that still influence our present.

10. Specialized Paths: A Glimpse into Diverse Archaeological Disciplines

Archaeology is a vibrant field with numerous specialized paths, each offering a distinct lens into the human past. This disciplinary breadth allows archaeologists to delve deeply into particular aspects of human interaction with environment, technology, and biology, revealing an astounding diversity in our collective heritage. These specializations demand focused expertise for comprehensive understanding of ancient life.

Bioarchaeologists, for instance, meticulously analyze human remains from archaeological sites. Their work reconstructs intricate details about ancient health, diet, diseases, and population movements. Employing techniques from physical anthropology, osteology, and forensic science, they vividly portray past individuals’ lives and experiences, revealing adaptations and challenges faced by our ancestors through their bones.

Environmental Archaeologists unravel complex interactions between past societies and their natural surroundings, studying botanical and faunal remains and ancient landscapes. They piece together how human activities impacted ecosystems, shaped agriculture, and responded to climate change. Similarly, Industrial Archaeologists investigate factories and infrastructure, shedding light on industrialization’s transformative impact. These specializations underscore archaeology’s expansive scope, telling the human story from countless material perspectives.

11. Underwater Worlds: The Realm of Maritime Archaeology

Beyond land-based discoveries, maritime archaeology explores an entire realm beneath the waves, investigating and preserving submerged archaeological sites. These can range from ancient shipwrecks to sunken cities, often safeguarding artifacts and structures in a unique state rarely seen on land. This offers an unparalleled window into past maritime activities and cultures, highlighting humanity’s long relationship with the sea.

Maritime archaeology presents profound challenges, necessitating specialized methodologies and equipment. Underwater archaeologists are skilled divers, adept at perilous environments, employing advanced remote sensing like sonar to locate sites. Every artifact requires careful documentation and recovery with techniques adapted for the underwater setting, ensuring contextual preservation.

Discoveries often reveal not just individual vessel tales, but broader narratives of ancient trade routes, naval warfare, and shipbuilding innovation. From Roman merchant ships to colonial-era wrecks, these sites are dynamic archives of human ingenuity. Collaboration with marine biologists and conservationists ensures artifact preservation and ecological understanding, enriching our knowledge of underwater cultural heritage.

12. Where the Past Comes to Life: The Archaeologist’s Workplace

The archaeologist’s workplace is remarkably diverse, spanning from rugged outdoor settings to advanced indoor facilities, reflecting the wide array of tasks involved. While fieldwork—surveying and excavating—is significant, the journey of discovery extends far beyond initial unearthing, encompassing rigorous analysis and diligent preservation. Field locations vary from remote deserts to bustling urban centers, often requiring physical labor and collaborative team efforts.

Beyond the field, the journey continues in laboratories, where recovered finds undergo intensive analysis. Techniques include radiocarbon dating, ceramic analysis, and microscopic examination. Specialized software is used for data analysis, mapping, and 3D modeling, transforming raw finds into scientific evidence. Museums are also crucial workplaces for cataloging, conservation, and curatorial tasks, ensuring proper artifact presentation.

Finally, the office environment facilitates extensive research, report writing, funding acquisition, and collaborative meetings. This blend of physical exertion, scientific rigor, and intellectual engagement truly defines the dynamic workplace of an archaeologist. Opportunities for travel, attending conferences, and field schools further enrich this demanding yet rewarding profession.

13. Anthropologist or Archaeologist? Defining the Disciplinary Lines

In human studies, “anthropologist” and “archaeologist” are often conflated, yet represent distinct disciplines with a hierarchical relationship crucial to understanding their contributions. Both professions share a profound curiosity about human existence, but approach inquiry from different angles and methodologies, though they frequently inform one another.

Anthropology, as a broader field, holistically studies human culture, society, and biology across all times and places. Anthropologists delve into aspects like social organization, cultural beliefs, linguistic structures, and human evolution. They employ qualitative research methods such as participant observation, interviews, and ethnographic research to understand contemporary cultures and societies, often immersing themselves in living traditions.

Archaeology, conversely, is a specialized subfield *within* anthropology. Its distinct focus is studying past human societies and civilizations through meticulous analysis of their material remains. Archaeologists investigate ancient settlements and sites, uncovering artifacts and structures to reconstruct history, technology, social structures, and cultural practices, especially from periods lacking written records. While all archaeologists are anthropologists, not all anthropologists are archaeologists, as their scope extends to contemporary societies and other biological dimensions of humanity.

14. Pioneers and Foundations: A Brief History of Archaeological Development

The journey of archaeology from a curious pastime to a rigorous scientific discipline is a fascinating narrative, rooted in early antiquarian pursuits. While humans have always been intrigued by ancestral vestiges, the systematic study of remains coalesced in 19th-century Europe, growing from multi-disciplinary antiquarianism. Early scholars sought to understand history through empirical evidence from ancient artifacts, manuscripts, and sites.

Traces of archaeological thought appear much earlier. King Nabonidus of Mesopotamia, circa 550 BCE, engaged in what could be considered first archaeological excavations. Later, Cyriacus of Ancona, 15th century, meticulously recorded Greek and Roman antiquities. In Song dynasty China, Ouyang Xiu and Zhao Mingcheng established traditions of epigraphy, investigating ancient bronze inscriptions, showcasing early, albeit distinct, forms of material study.

The Enlightenment saw tentative steps towards systematization. Early excavations like John Aubrey’s at Stonehenge (late 17th century) and Roque Joaquín de Alcubierre’s at Pompeii (mid-18th century) made significant finds but lacked methodological rigor. Johann Joachim Winckelmann in the mid-18th century applied systematic style categories to art history, distinguishing Greek art into periods, marking a crucial intellectual shift.

The 19th century was transformative with stratigraphy development—understanding that soil and artifact layers correspond to successive periods—borrowed from geology. Pioneers like William Cunnington meticulously recorded barrows. Augustus Pitt Rivers, the first scientific archaeologist, insisted on collecting *all* artifacts, arranging them typologically and chronologically. William Flinders Petrie revolutionized dating through pottery analysis. Later, Sir Mortimer Wheeler pioneered the highly disciplined grid system of excavation in the early 20th century, refined by Kathleen Kenyon, solidifying archaeology as a truly scientific and essential discipline.

This journey through archaeology’s diverse facets—from its specialized fields and dynamic workplaces to its historical evolution and critical distinctions—underscores its profound importance. As new civilizations are unearthed and ancient mysteries solved, archaeology continuously rewrites our human story, enriching our understanding of where we come from and what it truly means to be human. It stands as an ongoing testament to humanity’s enduring quest to connect with its past, offering invaluable lessons for our present and future.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(902x701:904x703)/Taylor-Swift-Travis-Kelce-Amsterdam-070624-03-b71d09f4779b4d109dc7be8f2f372e15.jpg)