.jpg)

The 1970s, often perceived through a hazy lens of disco balls and bell-bottoms, was in fact a decade of profound global upheaval—a true “pivot of change,” as historians in the 21st century have increasingly portrayed it. Far from being merely a backdrop for burgeoning youth culture, these ten years from 1970 to 1979 witnessed the dramatic rise and precipitous fall of powerful ideologies, entrenched political systems, and towering figures whose influence once seemed boundless. This era was a crucible, forging new global realities from the ashes of old orders, often with startling speed and irreversible consequence.

In an age where the concept of “teen idol” typically conjures images of ephemeral pop stars, the 1970s presented a different, more substantial kind of fleeting prominence. This was a time when grand narratives—of economic stability, political détente, and enduring imperial might—dominated the global stage, only to experience an equally dramatic retreat or collapse. What follows is an in-depth examination of twelve such ‘idols’ of influence, these foundational elements of the 20th century, which, like any celebrity, were everywhere until, suddenly, they weren’t.

Our journey through this transformative decade reveals not just the stories of individual prominence and decline, but also the broader cultural shifts and societal observations that Vanity Fair is known for illuminating. We delve into the complexities and untold stories behind these public figures and events, painting vivid pictures of an era marked by profound transitions. From the grand geopolitical strategies that sought to stabilize a fractured world to the enduring legacies of colonial rule, each ‘idol’ offers a window into the dynamic and often tumultuous spirit of the 1970s, where change was the only constant and yesterday’s certainty was tomorrow’s historical footnote.

1. **Détente: The Easing of Tensions That Couldn’t Last**

As the 1970s opened, a discernible shift occurred in superpower relations. Following decades of tense Cold War confrontations that risked nuclear war, a new policy of détente emerged, promoting resolution through negotiation. This strategic departure from earlier brinkmanship offered hope for global peace. Both the United States and the Soviet Union, despite their ideological rivalry, endorsed nuclear nonproliferation and sought to lessen conflict, influencing foreign policy and arms control.

Despite the public spirit of détente, the US-Soviet geopolitical rivalry continued in more indirect ways. The superpowers relentlessly vied for influence over smaller nations, turning regions across Asia, Africa, and Latin America into proxy battlegrounds. Their intelligence agencies supported various groups and governments, each side aiming for geopolitical advantage. Even in Europe, Soviet-backed Marxist terrorist groups operated, signifying the persistent ideological struggle beneath the surface of official détente.

The optimistic policy of détente met an abrupt end with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979. This aggressive military action shattered the premise of peaceful coexistence, abruptly reigniting Cold War tensions. Widely condemned, the invasion demonstrated the Soviet Union’s willingness to use force, directly challenging the notion of negotiated solutions. What was once a pervasive global policy suddenly wasn’t, replaced by renewed suspicion and a more hawkish stance, redefining superpower relations.

2. **Keynesian Economic Theory: The Unraveling of an Orthodoxy**

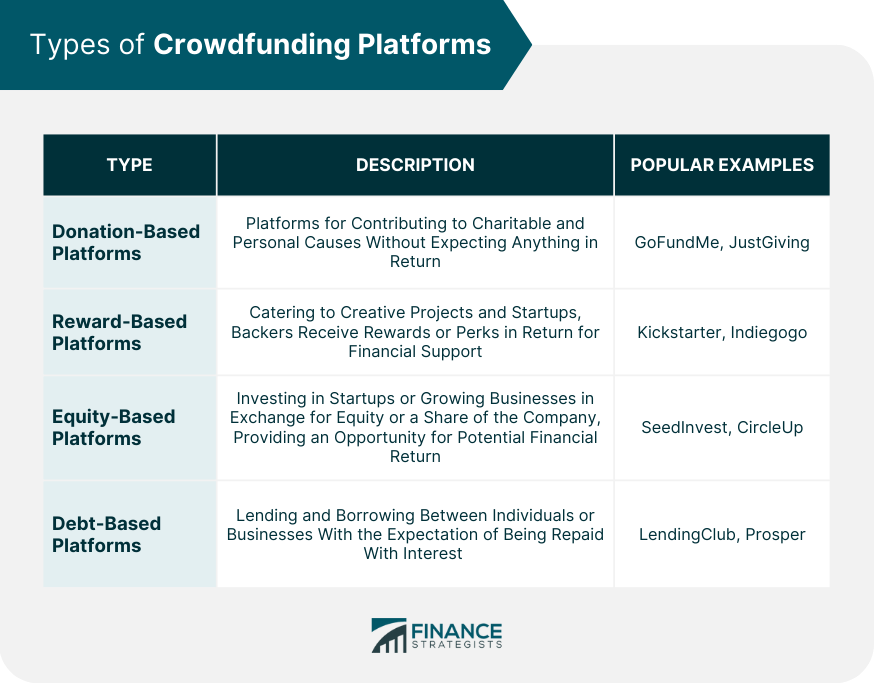

For much of the post-World War II era, Keynesian economic theory dominated industrialized countries, serving as the bedrock of governmental policy. This influential thought advocated for state intervention—through fiscal and monetary policies—to stabilize economic cycles and achieve full employment. Its principles were widely accepted as conventional wisdom, deeply embedded in Western economic frameworks and credited for the post-war economic boom. Keynesianism was an omnipresent intellectual force, shaping responses to recessions and booms.

Keynesian theory faced an unprecedented challenge in the 1970s: stagflation. This economic nightmare combined stagnant growth and high unemployment with rising inflation, baffling Keynesian models. The 1973 oil crisis, caused by OPEC embargoes, triggered dramatic oil price spikes, increasing production costs and fueling inflation while economies slowed. This external shock exposed a critical vulnerability, as traditional tools against recession or inflation proved ineffective, raising serious questions about Keynesianism’s universal applicability.

The failure of Keynesian economics to address stagflation created an ideological void. This led to a significant trend: its replacement by neoliberal economic theory. Neoliberalism advocated for free markets, deregulation, and reduced government spending as solutions. The 1973 Chilean coup d’état brought the first neoliberal government to power, and Margaret Thatcher’s 1979 UK election victory cemented this shift, initiating an agenda of reduced spending and liberalization. What was once “everywhere” as the dominant economic paradigm suddenly wasn’t, marking a profound reorientation of global economic thought.

3. **The Postwar Economic Boom: From Golden Age to Economic Upheaval**The decades following World War II brought sustained economic prosperity to the developed world, known as the postwar economic boom. Characterized by robust industrial growth, burgeoning international trade, and significantly improved living standards, this era instilled a pervasive sense of optimistic progress. Economies expanded, opportunities multiplied, and full employment was often achieved. Governments and citizens grew accustomed to this upward trajectory, viewing it as the natural order, a testament to effective policies and global cooperation.

The decades following World War II brought sustained economic prosperity to the developed world, known as the postwar economic boom. Characterized by robust industrial growth, burgeoning international trade, and significantly improved living standards, this era instilled a pervasive sense of optimistic progress. Economies expanded, opportunities multiplied, and full employment was often achieved. Governments and citizens grew accustomed to this upward trajectory, viewing it as the natural order, a testament to effective policies and global cooperation.

As the 1970s unfolded, strains began to appear in the postwar economic boom’s edifice. While developing world economies, aided by the Green Revolution, initially progressed steadily, they too felt emerging global headwinds. Underlying vulnerabilities gradually surfaced. Global competition intensified, and the seemingly endless supply of cheap energy—a key ingredient for industrial expansion—began to be questioned. These nascent signs suggested the boom’s powerful engine was losing momentum, foreshadowing dramatic upheavals.

The postwar economic boom definitively ended in the 1970s, primarily triggered by the 1973 oil crisis. OPEC embargoes caused oil prices to soar, plunging industrialized nations into severe recession and sparking global economic upheaval. Historians portray the 1970s as a “pivot of change,” focusing on these economic shifts. The oil crisis also instigated stagflation—simultaneous stagnation and inflation—which defied conventional wisdom. What was “everywhere” as pervasive growth suddenly wasn’t, forcing nations to confront a new reality of limited resources and interdependence.

4. **Colonial Empires (Portuguese and Spanish): The Final Sunset**

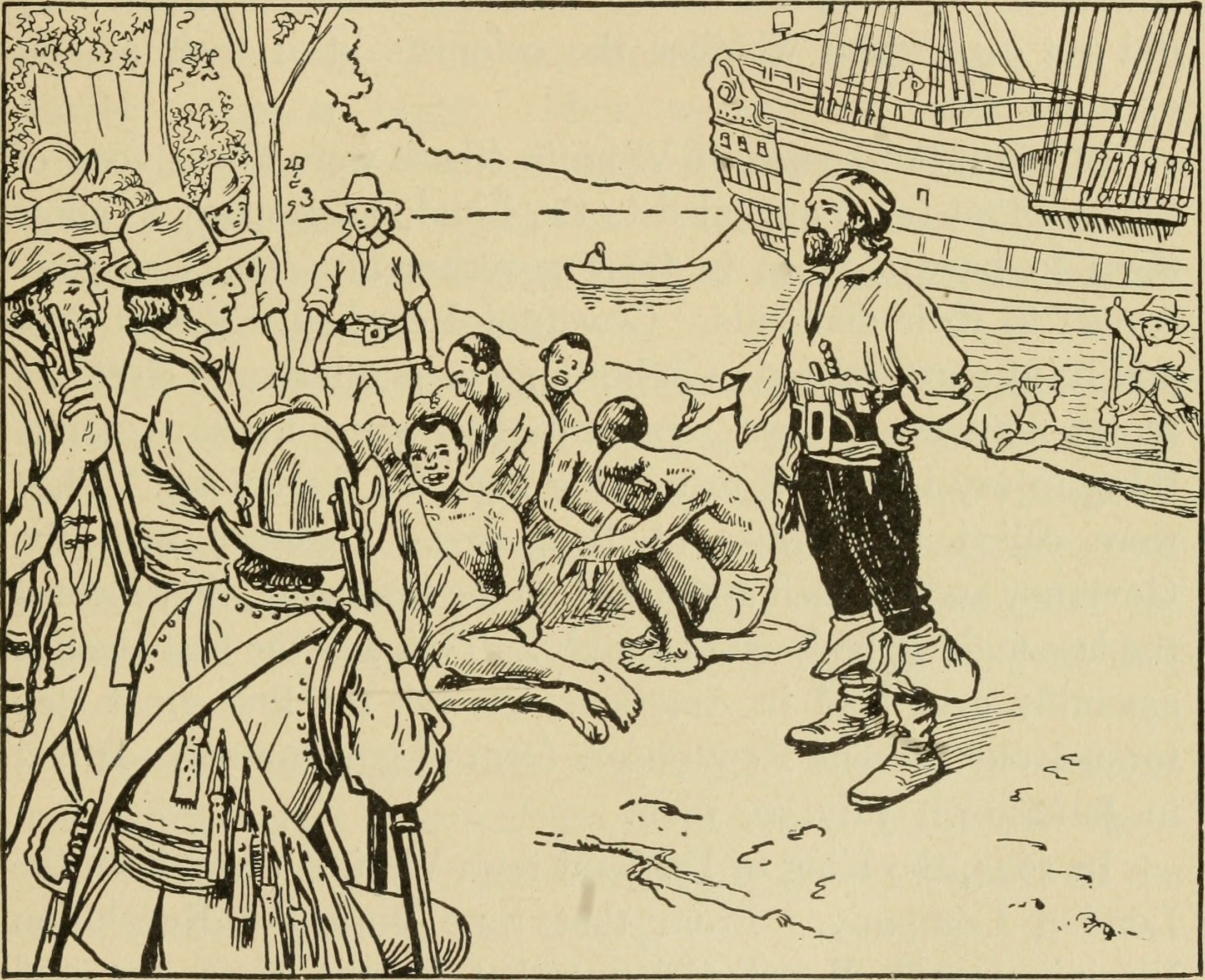

At the dawn of the 1970s, the legacies of European colonialism still persisted in Africa, particularly in Portuguese territories like Angola and Mozambique, and Spain’s Spanish Sahara. These empires, some of the oldest, maintained a firm grip, dictating political structures and exploiting resources. The Portuguese Colonial War raged, underscoring Portugal’s determination despite international pressure. These colonial presences were “everywhere” in their respective regions, dictating daily life and representing enduring imperial authority.

The Portuguese Empire’s grip was fundamentally challenged not externally, but by a dramatic internal upheaval: the Carnation Revolution of April 25, 1974. Originating as a military coup against the fascist regime, it quickly gained widespread popular support, transforming into a largely peaceful uprising. This revolution was fueled by dissatisfaction with authoritarianism, the economic drain of colonial wars, and a desire for democracy. The costly conflicts had become unpopular, linking Portugal’s internal political transformation to its colonies’ fate.

The Carnation Revolution’s consequences were immediate for the remaining colonies. Angola and Mozambique gained independence in 1975, marking the definitive end of nearly five centuries of Portuguese imperial rule. This rapid decolonization, while liberating, regrettably led to civil wars in these newly independent nations. Similarly, Spain withdrew its claim over Spanish Sahara in 1976, marking the formal end of the Spanish Empire. What had been “everywhere” as symbols of European power suddenly weren’t, fundamentally redrawing Africa’s political map and conclusively ending an era.

5. **US Involvement in the Vietnam War: The End of a Long Chapter**

As the 1970s began, the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War was an all-consuming national obsession, pervasive in American life and global geopolitics. The conflict dictated foreign policy, fueled massive military spending, and profoundly divided society. It was “everywhere”—on television, in protests, in debates, deeply ingrained in the national consciousness. This monumental commitment aimed to stem communism, shaping an entire generation and significantly impacting America’s world standing.

Political pressure against America’s involvement reached a crescendo in the early 1970s. Leaked information, mounting casualties, and growing anti-war movements eroded public and congressional support. The protracted, seemingly unwinnable conflict led to re-evaluation of its costs. The US began disengagement, gradually withdrawing forces and implementing “Vietnamization” to empower South Vietnamese forces. This strategic pivot marked the reluctant but firm decision to wind down an increasingly unpopular war.

America’s formal withdrawal concluded in 1973, but the war itself persisted. The cessation of direct US military engagement left South Vietnam vulnerable, leading to the Fall of Saigon in 1975. On April 30, the capital fell, resulting in South Vietnam’s unconditional surrender and evacuations. The following year, Vietnam was officially reunited under communist rule. What was “everywhere” as a central pillar of American foreign policy suddenly wasn’t, closing a long chapter and fostering introspection about interventionism.

Read more about: Robert Jay Lifton: A Psychiatrist’s Profound Journey Into Humanity’s Extreme Situations and the Quest for Understanding Evil, Dead at 99

6. **Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s Monarchy in Iran: From Pro-Western Ally to Revolutionary Overthrow**

For decades, Iran, under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, served as a crucial pro-Western monarchy. His autocratic rule was “everywhere,” permeating political life and driving ambitious modernization programs fueled by oil wealth. He envisioned a rapid Westernization, challenging traditional Islamic values. Allied with Western powers, especially the US, the Shah was a pillar against Soviet influence and a figure of immense power, his decisions shaping Iran and its significant role in regional and global oil politics.

Despite outward stability, deep discontent simmered beneath the Shah’s rule. His modernization, often disruptive, alienated traditionalists and clergy. The autocratic regime, marked by suppressed dissent and human rights abuses, fueled widespread opposition from intellectuals and political groups. Economic prosperity was accompanied by inequality and corruption, eroding legitimacy. His reliance on Western support also led to accusations of being a foreign puppet, subtly undermining his seemingly unassailable authority.

Political tensions erupted into the 1979 Iranian Revolution, dramatically overthrowing the Pahlavi dynasty. Iran transformed from a pro-Western monarchy to a theocratic Islamist government led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The Shah was forced into exile in January; Khomeini returned in February. What was “everywhere” as the ruling power suddenly wasn’t, replaced by a radically different system. This led to the Iran hostage crisis in November 1979 and profoundly altered global attitudes, marking the complete dismantling of a once-ubiquitous political entity.

Continuing our exploration into the profound transformations of the 1970s, we turn our gaze to yet another set of ‘teen idols’—the powerful regimes, deeply embedded political structures, and defining conflicts that, once considered immovable fixtures on the global stage, were dramatically dismantled or fundamentally redefined by the close of this tumultuous decade. These were not just shifts in policy, but seismic reconfigurations of entire societies, embodying the era’s relentless march of change.

7. **Haile Selassie’s Monarchy in Ethiopia: The Fall of an Ancient Lineage**

For centuries, the Ethiopian monarchy, embodied by Emperor Haile Selassie, stood as a symbol of continuity and ancient power, its influence pervasive across the nation and recognized globally. This was a realm where tradition held sway, and the emperor’s rule, despite underlying societal pressures, seemed an unyielding fixture of African political life, representing one of the world’s longest-lasting monarchies. His stately presence and historical lineage marked Ethiopia as a distinctive and enduring entity in a rapidly changing continent.

However, the 1970s brought an abrupt end to this venerable institution. A military coup in Ethiopia, which began in 1974, dramatically toppled Haile Selassie from power. This internal upheaval, fueled by growing dissatisfaction with the authoritarian regime and mounting economic and social issues, rapidly gained momentum, revealing the fragility beneath the surface of seemingly eternal rule. The pressures of modern governance and widespread calls for change ultimately overwhelmed the historical precedent.

The coup culminated in the overthrow of Haile Selassie, marking the definitive end of a monarchy that had persisted through millennia. A communist junta, led initially by General Aman Andom and later by Mengistu Haile Mariam, seized control. What had been a ubiquitous symbol of ancient African sovereignty suddenly wasn’t, replaced by a radically different political order that forever altered Ethiopia’s trajectory and dissolved a foundational aspect of its identity.

8. **The Spanish Dictatorship Under Francisco Franco: From Authoritarian Grip to Democratic Dawn**

For nearly four decades, the iron grip of Francisco Franco’s dictatorship defined Spain, permeating every aspect of political and social life. His authoritarian rule, established in 1939, was a pervasive and unyielding force, stifling dissent and shaping the nation’s direction with an absolute authority that seemed beyond challenge. This formidable regime, once an omnipresent reality for the Spanish people, cast a long shadow over the European continent, representing a relic of an earlier, more autocratic age.

The seismic shift arrived with Franco’s death in 1975, a moment that abruptly removed the lynchpin of the entire system. Following his demise, King Juan Carlos I ascended to the throne, and with remarkable foresight and courage, he immediately called for the reintroduction of democracy. This pivotal decision signaled an unequivocal break from the past, setting Spain on an irreversible course toward liberalization and marking the beginning of a profound political transformation.

The transition to democracy was swift and comprehensive. The first general elections were held in 1977, ushering in a new era of political representation. Previously outlawed parties, including the Socialist and Communist parties, were legalized, and a new, progressive Spanish Constitution was signed in 1978. What was once the unyielding power of a totalitarian dictatorship suddenly wasn’t, replaced by a vibrant parliamentary democracy, fundamentally redefining Spain’s place in the modern world.

9. **China’s Maoist Orthodoxy and Isolation: The Cracks in the Ideological Wall**

Throughout the early 1970s, the People’s Republic of China remained largely defined by the pervasive ideological orthodoxy of Mao Zedong and a stance of significant international isolation, a direct consequence of the Cultural Revolution and the geopolitical landscape. Mao’s revolutionary vision and strict communist principles were everywhere, shaping domestic policy and public life, while China’s relationships with the wider world were limited, only just beginning to change after its recognition by the United Nations.

A profound turning point arrived in 1976 with the deaths of both Mao Zedong and his premier, Zhou Enlai. These monumental losses signaled the undeniable end of an era, creating a leadership vacuum and opening the door for new political directions. After a brief period under Mao’s chosen successor, Hua Guofeng, Deng Xiaoping emerged as China’s paramount leader. Deng initiated a strategic and far-reaching shift away from strictly ideologically driven policies toward market economics, signaling a radical reorientation of the nation’s future.

This internal re-evaluation was mirrored by significant shifts in China’s international relations. President Richard Nixon’s historic visit in 1972, following earlier visits by Henry Kissinger, had already begun to thaw relations with the United States, though formal diplomatic ties were not established until 1979. This movement towards openness, combined with Deng Xiaoping’s visit to the US in 1979, fundamentally redefined China’s global posture. What was once a deeply isolated and ideologically rigid nation suddenly wasn’t, moving towards greater engagement and economic liberalization, profoundly altering the geopolitical balance.

10. **Idi Amin’s Regime in Uganda: A Brutal Reign’s Abrupt End**

In 1971, Idi Amin seized power in Uganda through a military coup, swiftly establishing a brutal dictatorship that became omnipresent in the lives of his citizens and notorious on the international stage. His regime was characterized by widespread persecution of political opposition and a deeply racist agenda, most notably the expulsion of Asians from Uganda, many of whom had resided there since British colonial rule. Amin’s tyrannical rule and erratic pronouncements created an atmosphere of fear and instability throughout the country.

Driven by an expansionist agenda, Amin initiated the Ugandan–Tanzanian War in 1978, forming an alliance with Libya in a bid to annex territory from neighboring Tanzania. This audacious military venture, born from the dictator’s hubris and desire for regional dominance, proved to be a critical miscalculation. The conflict escalated, drawing international attention and resources, and stretching Amin’s forces thin as Tanzania mounted a robust defense.

The war ultimately led to the dramatic downfall of Amin’s regime. In 1979, Ugandan forces, supported by Tanzania, suffered a decisive defeat, which directly culminated in Amin’s overthrow. What had been a seemingly entrenched and terrifying dictatorship suddenly wasn’t, its brutal rule collapsing under the weight of its own aggressions and the resistance it provoked. Amin was forced into exile, marking the abrupt conclusion of a dark chapter in Uganda’s history.

11. **The Enduring Arab-Israeli Conflict: A Landmark Shift Towards Peace**

For decades, the Arab-Israeli conflict was a pervasive and defining feature of the Middle East, its tensions and hostilities deeply ingrained in regional and global geopolitics. This enduring state of conflict was tragically underscored by the Yom Kippur War in October 1973, when Egypt and Syria launched a coordinated attack against Israel to reclaim territories lost in the 1967 conflict. The war, a stark reminder of the deeply entrenched hostilities, further solidified the perception of an intractable and omnipresent struggle.

Yet, as the 1970s progressed, a remarkable and unprecedented diplomatic shift began to unfold. In a bold move towards reconciliation, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat engaged in peace negotiations with Israel. These efforts culminated in the historic Camp David Accords, signed in 1978 in the United States, an ambitious attempt to resolve the outstanding disputes that had fueled decades of warfare and suspicion. The accords represented a profound departure from the entrenched cycle of conflict.

The diplomatic breakthroughs at Camp David led directly to the signing of the 1979 Egypt–Israel peace treaty, a truly landmark achievement that fundamentally altered the dynamics of the Middle East. This treaty officially ended the state of war between the two nations, earning both Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin the Nobel Peace Prize. What had been everywhere as an incessant and defining conflict suddenly wasn’t, replaced by a formal peace, demonstrating the transformative power of dialogue in a region long accustomed to animosity.

12. **Yugoslavia’s Centralized Power: The Seeds of Decentralization and Discontent**

In the early 1970s, Yugoslavia, under the unwavering leadership of its communist ruler Joseph Broz Tito, presented a facade of pervasive, centralized power and national unity. Tito’s authority, though absolute, was delicately balanced across its diverse republics. However, this seemingly monolithic structure faced its first significant internal challenge with the emergence of the Croatian Spring movement in 1971, a growing demand for greater decentralization of power to Yugoslavia’s constituent republics.

Tito, while swiftly subduing the Croatian Spring movement and arresting its leaders to maintain order, recognized the underlying currents of discontent. In a shrewd move that both asserted his control and acknowledged the need for reform, he initiated a major constitutional overhaul, resulting in the 1974 Constitution. This document significantly decentralized powers to the republics, notably granting them the official right to separate from Yugoslavia, a concession that fundamentally reshaped the federal structure.

While the 1974 Constitution also consolidated Tito’s dictatorship by proclaiming him president-for-life, its provisions simultaneously weakened the influence of Serbia, Yugoslavia’s largest republic, by granting significant powers to its autonomous provinces of Kosovo and Vojvodina. This complex rebalancing, while intended to stabilize, ultimately proved to be a double-edged sword: it became resented by Serbs and unwittingly initiated a gradual escalation of ethnic tensions. What was once a seemingly immutable, centrally controlled entity suddenly wasn’t, its foundations subtly eroded by the very reforms designed to preserve it, sowing the seeds for future fragmentation.

As we look back at the 1970s, it becomes strikingly clear that this decade was far more than a period of fleeting fashion and ephemeral trends; it was a crucible where entrenched powers, global ideologies, and long-standing political systems were put to the ultimate test. Each ‘idol’ we’ve examined, from the grand aspirations of détente to the ancient lineage of an emperor, from the suffocating grip of dictatorships to the unifying promise of peace treaties, reveals the profound truth that even the most seemingly ubiquitous forces can vanish or be irrevocably transformed. The 1970s stands as a powerful testament to the relentless, often sudden, and always dramatic march of history, reminding us that yesterday’s certainty is indeed tomorrow’s historical footnote.