America. The land of the free, the home of the brave, and a nation forged in a crucible of monumental events that continue to define its character. Forget what you thought you knew about the ‘top’ lists; today, we’re not ranking comfort foods or hidden gems, but diving deep into the very fabric of American history itself. It’s a journey not just through time, but through the very soul of a country that has continuously reinvented itself.

From the fiery sparks of revolution to the profound struggles for equality, the United States has journeyed through a series of transformative eras, each leaving an indelible mark. These weren’t just isolated incidents; they were seismic shifts that reshaped its borders, its people, and its place on the world stage, culminating in the complex, diverse, and powerful nation we recognize today. Each era presented its own unique challenges and triumphs, fundamentally altering the trajectory of the young republic.

So, buckle up, because we’re taking a thrilling ride through the moments that truly define America. This isn’t just a history lesson; it’s an exploration of the foundational battles, ingenious ideas, and sheer will that propelled a nascent group of colonies into a global superpower. Prepare to discover the epic turning points that make America, well, America, and understand why these historical showdowns still resonate in its contemporary identity.

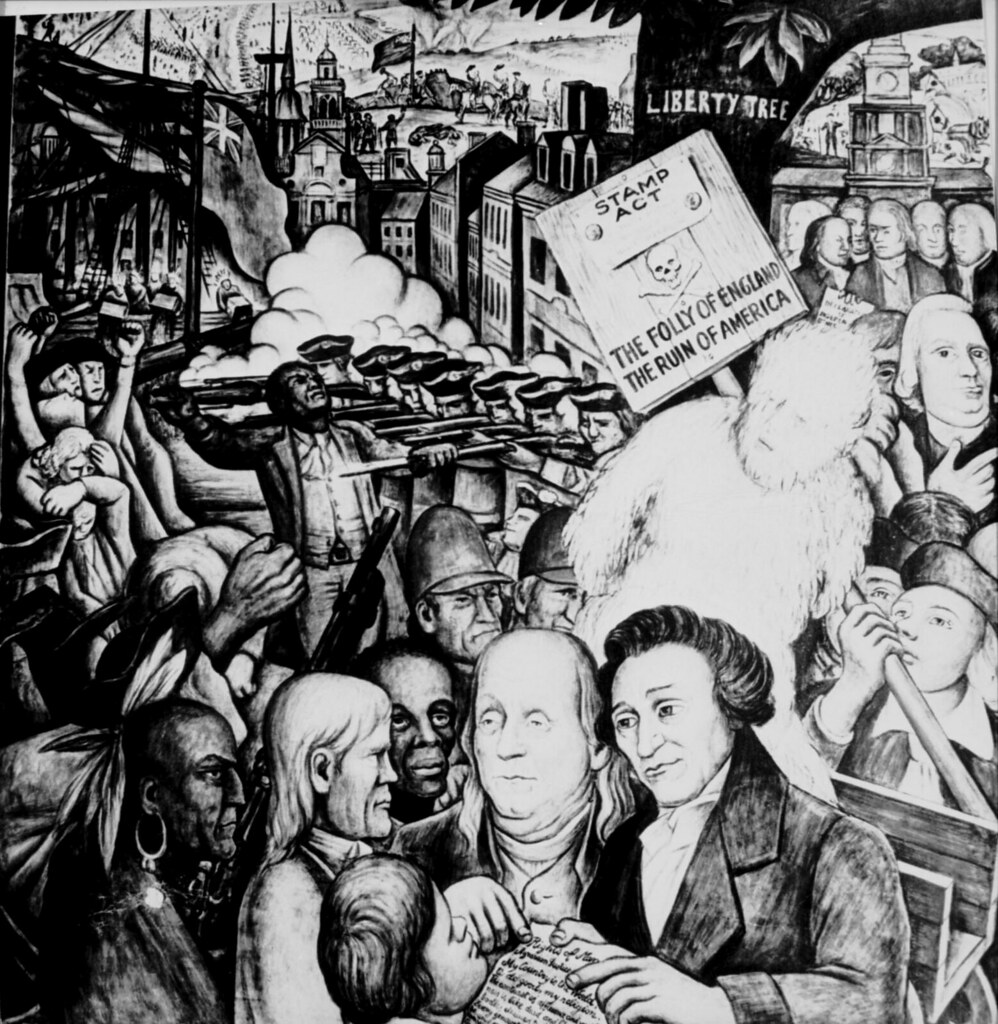

1. **The Birth of a Nation: The American Revolution and Declaration of Independence** Imagine a time when the burgeoning colonies, administered as possessions of the British Empire, chafed under Crown-appointed governors despite having local elections for most white male property owners. British assertiveness grew after their victory in the French and Indian War, leading to increased control over local colonial affairs. This sparked significant political resistance, as a primary grievance was the denial of their rights as Englishmen, particularly representation in the British government that taxed them. To demonstrate their dissatisfaction and resolve, the First Continental Congress met in 1774 and passed the Continental Association, a colonial boycott of British goods that proved remarkably effective.

The British attempt to disarm the colonists then ignited the American Revolutionary War with the Battles of Lexington and Concord in 1775. Amidst this rising conflict, the Second Continental Congress convened and appointed George Washington commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. A pivotal committee was formed, tasking Thomas Jefferson with drafting what would become the Declaration of Independence. On July 4, 1776, just two days after passing the Lee Resolution to create an independent nation, this groundbreaking document was adopted, formally announcing the colonies’ separation from Britain.

The political values born from the American Revolution were nothing short of revolutionary themselves. They championed liberty, inalienable individual rights, and the profound sovereignty of the people. This movement vigorously supported republicanism, rejecting monarchy, aristocracy, and all forms of hereditary political power, while fiercely vilifying political corruption. The Founding Fathers, including luminaries like Washington, Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin, drew deep inspiration from Classical, Renaissance, and Enlightenment philosophies and ideas, weaving them into the very fabric of the new nation’s ethos.

Although it had been in practical effect since its drafting in 1777, the Articles of Confederation were formally ratified in 1781, establishing a decentralized government that would operate until 1789. The British surrender at the siege of Yorktown in 1781 sealed the victory. American sovereignty was internationally recognized by the Treaty of Paris in 1783, a landmark agreement through which the U.S. gained vast territory stretching west to the Mississippi River, north to present-day Canada, and south to Spanish Florida, laying the groundwork for future expansion.

2. **Foundational Framework: The U.S. Constitution and its Enduring Legacy** The nascent nation quickly recognized the limitations of the Articles of Confederation, which had created a government too decentralized to effectively address the challenges facing the young republic. To overcome these inherent weaknesses, the U.S. Constitution was meticulously drafted at the 1787 Constitutional Convention. This monumental document went into effect in 1789, creating a robust federal republic governed by three separate branches, each meticulously designed to ensure a system of checks and balances, preventing any single branch from becoming supreme.

Under this new Constitution, George Washington was unanimously elected as the country’s first president, setting a precedent for leadership. To allay the concerns of skeptics worried about the power of the more centralized government, the Bill of Rights, a series of amendments guaranteeing fundamental individual liberties, was adopted in 1791. Washington’s selfless resignation as commander-in-chief after the Revolutionary War and his later refusal to run for a third presidential term established critical precedents for the supremacy of civil authority and the peaceful transfer of power in the United States.

At its core, the U.S. national government is a presidential constitutional federal republic and a representative democracy, characterized by its distinct three separate branches. All three branches are strategically headquartered in Washington, D.C., symbolizing the centralized authority of the federal government. This intricate system ensures a division of responsibilities and powers, a hallmark of American governance.

The legislative branch, the U.S. Congress, is a bicameral body composed of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Senate consists of 100 members, with two residents from each state elected by that state’s voters for a six-year term, providing equal representation for every state. In contrast, the House of Representatives comprises 435 members, each elected for a two-year term by the constituency of a congressional district, with district boundaries decided by state legislatures to ensure equivalent populations.

Congressional election years for senators are cleverly staggered, meaning only one-third of them face election every two years, providing continuity. U.S. representatives, however, are all up for election simultaneously every two years. Congress wields significant power: it makes federal law, declares war, approves treaties, holds the critical “power of the purse,” and possesses the power of impeachment. Beyond legislation, one of its foremost non-legislative functions is the crucial power to investigate and oversee the executive branch, a responsibility often delegated to its bipartisan committees, facilitated by the power to issue subpoenas. Furthermore, the principle of federalism grants substantial autonomy to the 50 states, while 574 Native American tribes also retain sovereignty rights, including 326 Native American reservations, reflecting a complex tapestry of governance.

3. **A Continent Unfolds: The Louisiana Purchase and Westward Expansion** As the 18th century drew to a close, American settlers began pushing westward in ever-increasing numbers, driven by a powerful sense of manifest destiny—the belief in the nation’s divinely ordained expansion across North America. This territorial ambition reached an astonishing peak with the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. This single transaction, acquiring vast lands from France, nearly doubled the entire territory of the United States, irrevocably altering its geographical footprint and strategic outlook.

Despite the monumental acquisition, lingering issues with Britain persisted, eventually leading to the War of 1812, which was fought to a draw. Meanwhile, Spain continued to cede its territorial claims, transferring Florida and its Gulf Coast territory to the U.S. in 1819. The nation grappled with its growing size and the contentious issue of slavery, leading to the Missouri Compromise of 1820. This agreement admitted Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state, attempting to balance the conflicting desires of northern states to prevent slavery’s expansion and southern states to extend it into new territories. Crucially, the compromise prohibited slavery in all other lands of the Louisiana Purchase north of the 36°30′ parallel.

As Americans continued their relentless expansion into territories long inhabited by Native Americans, the federal government enacted increasingly forceful policies of Indian removal or assimilation. The most significant of these was the Indian Removal Act of 1830, a key policy championed by President Andrew Jackson. This draconian measure culminated in the infamous Trail of Tears (1830–1850), a period during which an estimated 60,000 Native Americans living east of the Mississippi River were forcibly removed and displaced to lands far to the west. This brutal forced march resulted in an estimated 13,200 to 16,700 deaths, a tragic chapter in American history, and settler expansion, combined with this influx of Indigenous peoples from the East, fueled the American Indian Wars west of the Mississippi.

The United States continued its aggressive territorial expansion, annexing the Republic of Texas in 1845. The 1846 Oregon Treaty then secured U.S. control of the present-day American Northwest, further solidifying its presence on the Pacific coast. A dispute with Mexico over Texas escalated into the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). Following a decisive U.S. victory, Mexico recognized American sovereignty over Texas, New Mexico, and California in the 1848 Mexican Cession. These acquired lands also encompassed the future states of Nevada, Colorado, and Utah, dramatically expanding the national domain. The California gold rush of 1848–1849 spurred an even larger migration of white settlers to the Pacific coast, intensifying confrontations with Native populations and leading to one of the most violent episodes, the California genocide of thousands of Native inhabitants, which tragically lasted into the mid-1870s as additional western territories and states were created.

4. **A Nation Divided: The American Civil War and the Abolition of Slavery** During the colonial period, slavery had been a legal and deeply entrenched institution in the American colonies, becoming the primary labor force in the large-scale, agriculture-dependent economies of the Southern Colonies, stretching from Maryland to Georgia. However, the practice began to face significant moral and political challenges during the American Revolution. Spurred by a powerful and active abolitionist movement that reemerged in the 1830s, states in the North progressively enacted laws to prohibit slavery within their boundaries, moving towards a free labor system. Simultaneously, support for slavery had paradoxically strengthened in Southern states, largely due to inventions like the cotton gin in 1793, which made slave labor immensely profitable for the Southern elites and their plantation economy.

Throughout the 1850s, this escalating sectional conflict regarding slavery was further inflamed by controversial national legislation passed by the U.S. Congress and contentious decisions handed down by the Supreme Court. In Congress, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 mandated the forcible return of escaped slaves to their owners in the South, even if they had found refuge in non-slave states, deeply angering abolitionists. The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 then effectively gutted the anti-slavery requirements of the earlier Missouri Compromise, allowing for popular sovereignty on the issue in new territories. Adding to the firestorm, the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision of 1857 ruled against a slave brought into non-slave territory, simultaneously declaring the entire Missouri Compromise to be unconstitutional, thus denying Congress the power to prohibit slavery in the territories. These and other explosive events exacerbated the tensions between North and South that would tragically culminate in the American Civil War (1861–1865).

The breaking point arrived in 1861 when, beginning with South Carolina, eleven slave-state governments voted to secede from the United States. They subsequently joined together to create the Confederate States of America, forming a rival nation based on the preservation of slavery. In response, all other state governments remained fiercely loyal to the Union, setting the stage for an unprecedented internal conflict. War finally broke out in April 1861 after the Confederacy launched a devastating bombardment of Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, marking the official start of the Civil War.

A transformative moment arrived with the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, issued by President Abraham Lincoln, which declared that all enslaved people in Confederate territory were free. Following this declaration, many freed slaves bravely joined the Union army, fighting for their own liberation and the preservation of the Union. The tide of the war began to turn decisively in the Union’s favor following the strategic 1863 Siege of Vicksburg and the pivotal Battle of Gettysburg. The Confederates, facing overwhelming pressure, finally surrendered in 1865 after the Union’s decisive victory in the Battle of Appomattox Court House, bringing an end to the brutal conflict and leading to the national abolition of slavery.

Read more about: Unraveling Presidential Impact: 10 Defining Moments in U.S. History Shaped by American Leadership

5. **Rebuilding and Reshaping: The Reconstruction Era and its Aftermath** Even before the final cannons of the Civil War fell silent, efforts toward reconstruction in the secessionist South had begun as early as 1862, aimed at readmitting the former Confederate states and integrating newly freed African Americans into society. However, it was only after the tragic assassination of President Abraham Lincoln that three crucial Reconstruction Amendments to the Constitution were ratified, designed to codify and protect civil rights nationally. These monumental amendments formally abolished slavery and involuntary servitude (except as punishment for crimes), promised equal protection under the law for all persons, and explicitly prohibited discrimination based on race or previous enslavement, fundamentally transforming the legal landscape of the nation.

As a direct consequence of these reforms and the presence of federal troops, African Americans seized the opportunity to take an active and vital political role in the ex-Confederate states during the decade following the Civil War. They participated in elections, held public office, and contributed to the rebuilding efforts, showcasing the potential for a truly multiracial democracy. The former Confederate states were gradually readmitted to the Union, a process that began with Tennessee in 1866 and concluded with Georgia in 1870, symbolically reuniting a fractured nation.

However, the promise of Reconstruction was short-lived and ultimately betrayed. The Compromise of 1877 is widely considered the end of this transformative era, as it resolved the contentious electoral crisis following the 1876 presidential election. As part of this political bargain, President Rutherford B. Hayes agreed to reduce the role of federal troops in the South, effectively removing the enforcement arm of federal civil rights policies. Immediately following this withdrawal, a powerful political faction known as the “Redeemers” began systematically evicting the “Carpetbaggers”—Northern individuals who had come South—and swiftly regained local control of Southern politics, explicitly in the name of white supremacy.

The consequences for African Americans were devastating. They endured a prolonged period of heightened, overt racism following the formal end of Reconstruction, an era often tragically referred to as the nadir of American race relations. A series of regressive Supreme Court decisions, most notably *Plessy v. Ferguson* (1896), systematically emptied the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments of their intended force, allowing Jim Crow laws to flourish unchecked throughout the South. This legal framework of racial segregation extended to “sundown towns” in the Midwest and institutionalized segregation in communities across the entire country, which was further reinforced by discriminatory policies like “redlining” later adopted by the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, cementing decades of systemic inequality.

Alright, you’ve journeyed through the crucible of America’s birth and its early, often brutal, expansion and transformation. But the story of this nation is far from over. If you thought the early years were a rollercoaster, prepare yourself, because what comes next is a series of seismic shifts that catapulted the U.S. onto the global stage, defined its modern identity, and continue to resonate in its ongoing societal showdowns. We’re about to explore the thrilling, sometimes tumultuous, eras that solidified America’s place as a global superpower and reveal the complex layers of its evolving character. These are the unsung chapters, the massive movements, and the radical transformations that truly made the America we know today.

We’re picking up right where we left off, plunging into the dramatic aftermath of the Civil War and the dawn of a new, industrialized America. Get ready for five more unforgettable moments that didn’t just happen *in* history, they *are* history.

6. **From Rebirth to Industrial Might: The Gilded Age and Progressive Era (1863–1917)** After the Civil War’s brutal end, the South faced a monumental task of reconstruction. This era saw remarkable efforts to mend a fractured nation and integrate newly freed African Americans into society. Crucially, the three Reconstruction Amendments to the Constitution were ratified, designed to solidify and safeguard civil rights across the nation. These landmark amendments nationally codified the abolition of slavery, promised equal protection under the law for all persons, and expressly outlawed discrimination based on race or previous enslavement, laying down a legal foundation for true equality.

Fueled by these groundbreaking reforms and the reassuring presence of federal troops, African Americans stepped onto the political stage in the ex-Confederate states during the decade following the war. They cast votes, held public office, and actively contributed to the gargantuan rebuilding efforts, offering a glimpse of a truly multiracial democratic future. As these former Confederate states gradually rejoined the Union, starting with Tennessee in 1866 and concluding with Georgia in 1870, the nation seemed poised for a more unified and equitable future.

But as is often the case with grand promises, the vision of Reconstruction was tragically short-lived. The Compromise of 1877, a political deal struck to resolve the contentious 1876 presidential election, effectively pulled the plug on federal protection. President Rutherford B. Hayes agreed to reduce the role of federal troops in the South, and almost immediately, a powerful faction known as the “Redeemers” swept into power, swiftly regaining local control of Southern politics under the banner of white supremacy.

The consequences for African Americans were nothing short of devastating. They were plunged into a prolonged period of intensified, overt racism—a dark chapter often called the nadir of American race relations. A series of regressive Supreme Court decisions, most notoriously *Plessy v. Ferguson* in 1896, systematically stripped the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments of their power. This opened the floodgates for Jim Crow laws to proliferate throughout the South, institutionalized segregation in communities across the entire country, and policies like “redlining” further entrenched systemic inequality for generations.

Yet, amidst this social turmoil, America was simultaneously experiencing an explosion of technological innovation and unprecedented economic expansion. The Gilded Age, aptly named for its glittering surface masking deep inequalities, was characterized by the exploitation of cheap immigrant labor and the meteoric rise of industrialists who amassed immense power by forming trusts and monopolies. Tycoons spearheaded expansion in critical sectors like railroads, petroleum, and steel, while the nation emerged as a pioneer in the burgeoning automotive industry. This rapid growth, however, came at a cost, creating significant increases in economic inequality, widespread slum conditions, and social unrest, which in turn spurred the growth of labor unions and socialist movements. This tumultuous period eventually gave way to the Progressive Era, a time characterized by significant reforms aimed at addressing the injustices and imbalances created by rampant industrialization and unchecked corporate power. Beyond the mainland, America was flexing its muscles internationally, acquiring Hawaii, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Guam, American Samoa, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, expanding its influence across oceans.

7. **Global Conflict and Domestic Upheaval: World War I and the Great Depression (1917–1940)** As the 20th century dawned, America, now a burgeoning industrial powerhouse, found itself increasingly entangled in global affairs. Though initially clinging to neutrality, the United States eventually entered World War I in 1917, joining forces with the Allies and dramatically tipping the scales against the Central Powers. This wasn’t just a military conflict; it was a profound moment that forced America to reckon with its role on the world stage, forever altering its isolationist tendencies and forging a new, more interconnected identity. The war effort galvanized the nation, demonstrating its immense capacity for mobilization and innovation.

The aftermath of the war ushered in a vibrant, yet ultimately fragile, era of prosperity and profound social change known as the Roaring Twenties. In 1920, a monumental constitutional amendment finally granted nationwide women’s suffrage, marking a massive leap forward for democratic principles and women’s rights. Beyond politics, this decade saw astonishing transformations in communication, with the widespread adoption of radio for mass communication and the nascent emergence of early television, connecting Americans in unprecedented ways and profoundly shaping a national popular culture.

However, this glittering façade of prosperity masked deep economic vulnerabilities, which tragically culminated in the Wall Street Crash of 1929. This catastrophic event triggered the Great Depression, an economic contraction of unparalleled scale that brought widespread unemployment, poverty, and despair across the nation. It was a crisis that tested the very resilience of the American spirit and forced a fundamental rethinking of the government’s role in the economy and society.

In response to this immense challenge, President Franklin D. Roosevelt unveiled the New Deal. This wasn’t just a band-aid; it was a sweeping, transformative plan built on “reform, recovery and relief.” It launched an unprecedented series of recovery programs and employment relief projects, creating jobs and stimulating the economy, alongside crucial financial reforms and regulations designed to prevent such a collapse from ever happening again. The New Deal fundamentally reshaped the relationship between government and its citizens, establishing a new social contract that expanded the federal government’s role in ensuring economic stability and social welfare.

8. **The Greatest Generation’s Fight: World War II (1941–1945)** Even as the nation wrestled with the lingering effects of the Great Depression, a new and far more dangerous storm was brewing across the globe. Initially, the United States maintained a stance of neutrality during World War II, a reflection of its deep-seated isolationist sentiment. However, the tide irrevocably turned in March 1941 when the U.S. began supplying crucial war materiel to the Allied powers, signaling its growing involvement. The defining moment arrived in December 1941, when the Empire of Japan launched a devastating attack on Pearl Harbor, forcing America directly into the heart of the global conflict.

America’s entry into World War II transformed the nation into a powerhouse of production and innovation. The country rapidly mobilized its industries and manpower, becoming the “arsenal of democracy.” It also undertook one of the most secretive and revolutionary scientific endeavors in human history: the development of the first nuclear weapons. The devastating use of these weapons against the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 brought the war to a swift, albeit controversial, end.

With the cessation of hostilities, the United States emerged as one of the “Four Policemen” – a group that also included the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and China – tasked with planning the post-war world order. Unlike many of its allies and adversaries, the U.S. emerged relatively unscathed from the global conflict, with its industrial capacity intact and its economic power significantly amplified. This war solidified America’s position on the world stage, granting it unprecedented international political influence and setting the stage for the next monumental chapter in its history.

9. **Two Superpowers, One Cold War: Social Revolution and the Space Race (1945–1991)** The end of World War II, while bringing peace, immediately ushered in a new era of global tension. The United States and the Soviet Union, former allies, quickly emerged as rival superpowers, each wielding immense political, military, and economic influence and vying for ideological dominance. This geopolitical standoff rapidly escalated into the Cold War, a decades-long struggle that reshaped international relations and deeply influenced domestic policies in both nations. The U.S. adopted a policy of containment, seeking to limit the USSR’s sphere of influence around the globe and often engaging in covert actions and regime changes against governments perceived to be aligned with Moscow.

This intense rivalry fueled an extraordinary technological race, most famously manifested in the Space Race. The United States, through sheer ingenuity and national will, ultimately prevailed, achieving the monumental feat of the first crewed Moon landing in 1969. This achievement not only demonstrated American scientific prowess but also served as a powerful symbol of its technological and ideological superiority in the global competition.

Domestically, the post-World War II period was a time of significant economic growth, rapid urbanization, and a booming population. However, this prosperity also brought simmering social injustices to a head. The Civil Rights Movement erupted, with figures like Martin Luther King Jr. becoming prominent leaders in the early 1960s, demanding an end to racial segregation and discrimination. President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration responded with the groundbreaking Great Society plan, which resulted in broad-reaching laws, policies, and a constitutional amendment designed to counteract the worst effects of lingering institutional racism, aiming to build a more just and equitable society.

Simultaneously, America experienced a powerful counterculture movement that sparked significant social changes. Attitudes towards recreational drug use and sexuality underwent a profound liberalization, challenging traditional norms. The movement also galvanized widespread opposition to U.S. intervention in Vietnam, encouraging open defiance of the military draft—a resistance that ultimately led to the end of conscription in 1973—and culminating in the total U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam in 1975. Furthermore, a significant societal shift in the roles of women led to a dramatic increase in female paid labor participation during the 1970s, reaching a point where, by 1985, the majority of American women aged 16 and older were employed, fundamentally reshaping the workforce and family dynamics.

As the century drew to a close, a monumental shift in global power occurred. The Fall of Communism and the dissolution of the Soviet Union from 1989 to 1991 officially marked the end of the Cold War. This left the United States as the world’s sole superpower, a position that solidified its global influence and reinforced the concept of the “American Century,” with the U.S. dominating international political, cultural, economic, and military affairs like never before. It was a new world order, and America was at its undisputed helm.

10. **Navigating a New Millennium: Contemporary Challenges (1991–Present)** With the Cold War in the rearview mirror, the 1990s ushered in what many consider the longest recorded economic expansion in American history. This era was characterized by a dramatic decline in U.S. crime rates and an explosion of technological innovation. Breakthroughs like the World Wide Web, the continuous evolution of the Pentium microprocessor, rechargeable lithium-ion batteries, the first gene therapy trial, and cloning either emerged from American ingenuity or were significantly advanced there. The Human Genome Project formally launched in 1990, and Nasdaq became the first U.S. stock market to trade online in 1998, truly kicking off the digital age.

Yet, the new millennium quickly presented its own formidable challenges. After leading an international coalition to expel an Iraqi invasion force from Kuwait in the Gulf War of 1991, America soon faced a threat closer to home. The devastating September 11 attacks in 2001 by the pan-Islamist militant organization al-Qaeda led to the launch of the “War on Terror,” initiating subsequent military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq that reshaped U.S. foreign policy and global security for decades to come.

Domestically, a booming economy experienced its own reckoning. The U.S. housing bubble reached its peak in 2007, triggering the Great Recession—the most significant economic contraction since the Great Depression. This period tested the resilience of American households and businesses, prompting extensive governmental responses to stabilize the financial system and stimulate recovery. The aftermath of this economic turmoil, combined with other societal pressures, has profoundly influenced the nation’s political landscape.

In the 2010s and early 2020s, the United States has grappled with increasing political polarization and worrying signs of democratic backsliding. This growing division culminated in a violent reflection of the country’s tensions: the January 2021 Capitol attack. During this unprecedented event, a mob of insurrectionists stormed the U.S. Capitol, attempting to prevent the peaceful transfer of power in what has been described as an attempted self-coup d’état. This moment starkly highlighted the profound challenges America faces in maintaining unity and upholding its democratic principles in an increasingly fractured society.

So there you have it – the epic saga of America’s historical showdowns. From its rebellious birth to its current complex challenges, the United States has always been a nation in perpetual motion, constantly redefining itself. It’s a land of fierce debates, undeniable triumphs, and ongoing quests for a more perfect union. What a ride, right? Whether you’re a history buff or just looking for the next big story, understanding these pivotal moments isn’t just about looking back; it’s about understanding the very DNA of a nation that continues to shape the world.