Ever heard the word “cult” tossed around in conversations, maybe when someone’s *really* into a new hobby or a super intense group? It’s a term that tends to grab attention, often sparking images of mysterious rituals and charismatic leaders. But have you ever stopped to wonder what “cult” actually means, beyond the sensational headlines or casual chat?

Turns out, it’s a whole lot more complex and nuanced than you might think! The concept of a cult has a fascinating history, evolving definitions, and has been an ongoing source of debate among scholars for decades. What one person calls a cult, another might see as a legitimate spiritual path or even a visionary organization.

So, buckle up, because we’re about to take a deep dive into the real talk about cults. We’re cutting through the noise to explore how academics, sociologists, and even governments have tried to define, classify, and understand these unique social groups. Get ready to have your mind opened and your perspective shifted as we unravel the intricate world of cults, from their ancient roots to modern-day controversies!

1. **The Elusive Nature of the Term ‘Cult’**

The word “cult” itself is a bit of a shapeshifter, isn’t it? In modern English, when we hear “cult,” it often comes with a loaded, pejorative vibe, immediately bringing up negative connotations. It’s frequently applied to groups accused of being abusive, coercive, or even likened to gangs, organized crime, and terrorist organizations. Yikes!

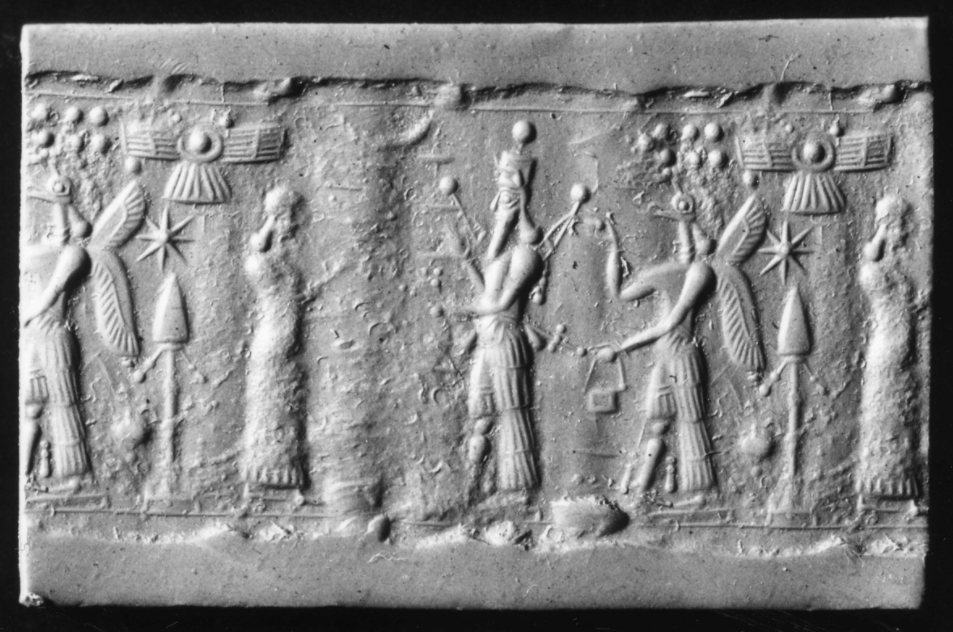

But here’s a fun fact: the word actually comes from the Latin term *cultus*, which simply means “worship.” Imagine that! So, historically, it just indicated a set of religious devotional practices that were conventional within a culture, often linked to a specific figure or place, or just the collective participation in religious rites.

Think about the “imperial cult of ancient Rome” – that’s an example where the word was used in a non-pejorative sense. It was all about conventional worship. It wasn’t until the 19th century that a derived sense of “excessive devotion” popped up, and its usage expanded beyond strictly religious contexts. This historical twist really highlights how much the meaning of words can transform over time.

As scholar Susannah Crockford puts it, “the word ‘cult’ is a shapeshifter, semantically morphing with the intentions of whoever uses it.” It resists a rigorous definition, making it a tricky term to pin down. She argues that perhaps the least subjective definition refers to a religion or religion-like group “self-consciously building a new form of society,” which the rest of society then rejects as unacceptable. Talk about a linguistic journey!

Read more about: Unearthing Ancient Powerhouses: The Top 10 Superfoods Revolutionizing Your Plate in 2024

2. **Sociological Roots: Weber’s & Troeltsch’s Influence**

Believe it or not, before the term “cult” got all its modern baggage, it was a legitimate subject of academic study! Starting way back in the 1930s, new religious movements, often perceived as cults, became a fascinating object of sociological study. Experts began analyzing them within the broader context of religious behavior, trying to understand what made these groups tick.

One of the O.G. theorists in this field was Max Weber, whose work from 1864–1920 laid some serious groundwork. Weber is super important for understanding cults because his ideas on “charismatic authority” are foundational. He also made a crucial distinction between “churches” and “sects,” which helped kickstart the academic conversation around religious group classifications.

Building on Weber’s brilliant insights, German theologian Ernst Troeltsch further elaborated on this “church–sect division.” He didn’t just stop there, though! Troeltsch cleverly added a “mystical” categorization to accommodate those more personal or individual religious experiences, showing that not all religious journeys fit neatly into boxes. These early sociological giants really set the stage for how we’d eventually categorize and understand the diverse world of religious movements.

So, next time you hear about a “cult,” remember that its academic journey began with these foundational theories, far from the dramatic portrayals we often see today. It’s a reminder that beneath the surface, there’s a rich history of intellectual inquiry trying to make sense of human belief and community.

3. **Becker’s Refinement: Cults as Unorganized Groups**

Just when you thought the definitions were getting clear, along came American sociologist Howard P. Becker to add another layer of complexity! He took Troeltsch’s church–sect framework and bisected it even further, making the distinctions even sharper. Becker split the “church” category into “ecclesia” and “denomination,” and then refined the “sect” category into “sect” and, you guessed it, “cult.” It’s like he was creating a more granular map for understanding religious landscapes.

In Becker’s view, a “cult” referred specifically to small religious groups that seriously lacked the kind of formal organization you’d find in a church or even a sect. These groups, according to Becker, placed a huge emphasis on the private nature of personal beliefs. Think of them as more intimate, less structured gatherings where individual spiritual journeys took center stage.

This sociological lens helps us understand that not all groups labeled “cults” are massive, centrally controlled organizations. Many, in their earliest forms or even enduringly, might simply be small clusters of individuals drawn together by shared, often unique, personal convictions. It’s a fascinating perspective that broadens our understanding beyond the popular, often fear-driven, imagery associated with the term.

Becker’s work truly illustrates how academic study tries to categorize and understand social phenomena without judgment, providing a framework that helps differentiate groups based on their structural and experiential qualities. It’s a key piece in the puzzle of deciphering what a ‘cult’ means in a sociological context.

4. **Deviant Beliefs and High Tension**

Moving forward from those foundational theories, later sociological formulations added even more depth to our understanding of cults. They started placing an additional emphasis on cults as religious groups that were seen as “deviant.” This wasn’t necessarily a moral judgment, but rather an observation that these groups often drew their inspiration from outside the predominant religious culture. They weren’t just a different flavor of the same old, they were something distinctly new and different.

Because of this “outside inspiration,” a high degree of tension often popped up between the cult group and the more mainstream culture surrounding it. It’s a bit like being the new kid in school who dresses completely differently – everyone notices, and sometimes there’s a bit of friction. This characteristic of high tension is actually something cults share with religious sects, creating a unique dynamic in society.

However, there’s a crucial distinction here: sects are typically seen as products of a religious schism, meaning they splintered off from a larger, established religion. So, while they might have new interpretations, they still maintain a continuity with traditional beliefs and practices. Cults, on the other hand, are often described as arising more spontaneously, forming around truly novel beliefs and practices that don’t necessarily have a direct lineage from existing religions. It’s a neat way to categorize new movements!

This distinction helps us appreciate that not all non-mainstream religious groups are the same. Some are offshoots, while others truly forge entirely new paths, leading to different kinds of societal interactions and reactions. It’s a testament to the ever-evolving nature of human spirituality and belief systems.

Read more about: 60s Movie Stars Who Vanished After Their Big Break: A Deep Dive into the Decade’s Most Mysterious Exits

5. **Bainbridge & Stark’s Three Cult Types**

Just when you thought we had a handle on cults, sociologists William Sims Bainbridge and Rodney Stark jumped in with an even more nuanced classification, proposing three distinct kinds of cults. Their work suggests that not all cults are created equal, and they certainly don’t all operate in the same way. It’s like a tiered system for understanding these diverse groups, all of which, they argued, share a common thread: offering a “compensator,” or rewards, for the things members invest into the group. This could be anything from spiritual fulfillment to a sense of community.

First up, they identified “cult movements.” These are actual, complete organizations, but here’s the kicker: they differ from a “sect” because they didn’t splinter off from a bigger, established religion. Instead, a cult movement is its own thing, a freestanding entity with its unique beliefs and structure. It’s a fresh start, not a breakaway faction.

Then there are “audience cults.” These are super interesting because they’re much more loosely organized. Think about groups that spread their ideas and gather followers primarily through media – maybe books, broadcasts, or online content. People might engage with the ideas without being part of a tightly knit, face-to-face community. It’s a more passive, widespread form of affiliation.

And finally, we have “client cults.” These are groups that offer specific services, often for a fee, like psychic readings, meditation sessions, or self-help workshops. They’re less about full-blown conversion and more about providing a particular experience or benefit to individuals. The cool thing is, one type can even morph into another; the Church of Scientology, for instance, is cited as an example of a group that transitioned from an audience to a client cult. Pretty wild, right?

It’s worth noting that sociologists who follow the Bainbridge-Stark classification are among the few academics who still consistently use the word “cult,” unlike many other scholars who’ve largely moved on to terms like “new religious movement.” However, even Bainbridge later admitted he regretted having used the word at all. They even challenged the traditional concept of “conversion,” suggesting that “affiliation” might be a more accurate term for how people join new religious groups. Talk about rethinking everything!

6. **The Role of Personal Relationships in Conversion**

Ever wondered what really draws people into new religious groups, sometimes against all odds? Back in the early 1960s, sociologist John Lofland decided to get up close and personal with members of the Unification Church in California, studying their efforts to promote their beliefs and win new followers. His findings were nothing short of groundbreaking, revealing a powerful truth about human connection.

Lofland observed that for all the effort members put into proselytizing, most of their direct outreach was actually pretty ineffective. It wasn’t slick pamphlets or grand sermons that did the trick! Instead, he found that the vast majority of people who eventually joined the Unification Church did so because of existing personal relationships with other members. Often, these were family relationships, highlighting the profound influence of interpersonal bonds.

This insight completely flipped the script on how we understand religious conversion. It suggested that rather than a sudden, dramatic intellectual shift, joining a new religious group was frequently a process deeply rooted in social networks and trust. It’s a reminder that even in seemingly radical life changes, the human need for connection and belonging plays a starring role.

Lofland’s eye-opening research was first published in 1964 as his doctoral thesis, “The World Savers: A Field Study of Cult Processes,” and then in book form in 1966 as *Doomsday Cult: A Study of Conversion, Proselytization, and Maintenance of Faith*. This work is still considered one of the most important and widely cited studies in the entire field of religious conversion. It truly emphasizes that sometimes, the most powerful persuaders aren’t ideas, but the people we already know and care about.

Read more about: The Truth About Bailee Madison Is Tumbling Out: Unraveling a Concept Deeper Than Celebrity

7. **The Rise of Academic Study in the 1970s**

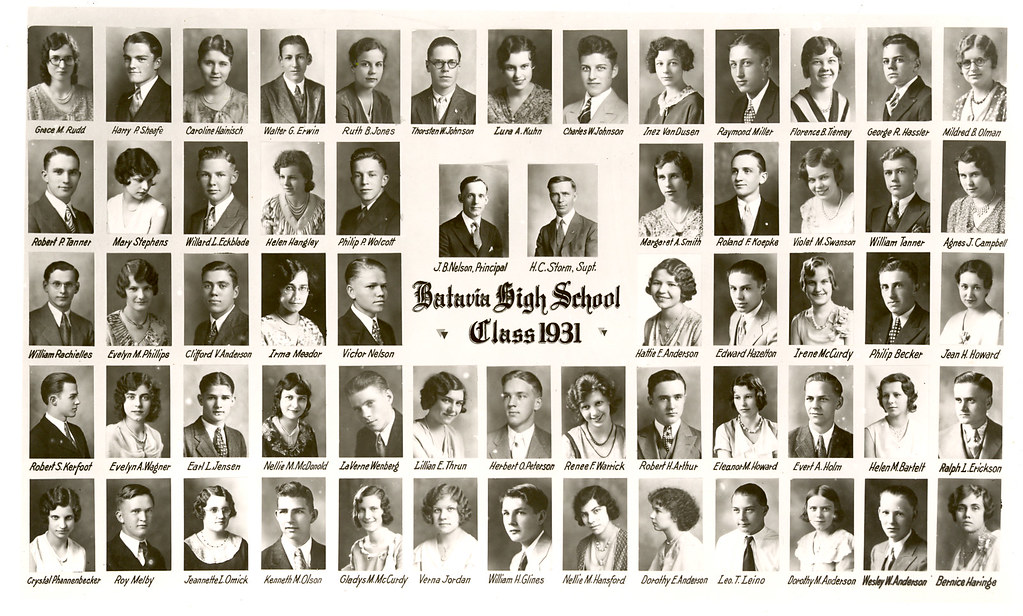

It’s hard to believe now, but if you rewind to 1970, the academic landscape for studying new religions was pretty sparse. J. Gordon Melton, a respected scholar in the field, noted that you could practically “count the number of active researchers on new religions on one’s hands.” It was a niche area, to say the least, and not yet the bustling academic subfield it would become.

However, things were about to change dramatically! According to James R. Lewis, writing in 2004, the “meteoric growth” in this field of study can be directly attributed to the “cult controversy” that really kicked off in the early 1970s. This period saw a significant “wave of nontraditional religiosity” sweeping across the globe, especially in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Academics suddenly found themselves confronted with a whole new array of religious innovations, distinct from previous spiritual movements. These “new religious movements” presented fresh challenges and questions, demanding dedicated study and analysis. It wasn’t just about understanding existing faiths anymore; it was about grappling with emerging spiritual phenomena that defied easy categorization and often sparked public debate. This surge in interest, fueled by societal changes and controversies, transformed a quiet corner of academia into a vibrant and essential area of research, ultimately shaping our contemporary understanding of diverse faith traditions.”

We’ve explored how “cult” is defined and its academic journey, but let’s be real, the term usually brings up images far from scholarly. It’s often linked to serious controversies and, frankly, the darker side of group dynamics. So, what happens when groups cross that line, and how have societies, even governments, dealt with them?

Get ready, we’re about to explore the more intense, sometimes unsettling, aspects of cults. This includes “destructive” and doomsday groups, how religious and secular movements have challenged them, and how different countries navigate policy. It’s a wild ride, so keep your mind open!

Read more about: Unpacking the Building Blocks of Thought: An Accessible Deep Dive into the World of Concepts

8. **When Things Go Sideways: The Destructive Cult**

Beyond academic definitions, many associate “cult” with “destructive cults.” This loaded term, used by the anti-cult movement, describes groups seen as unethical, deceptive, and manipulative. They’re accused of using “strong influence” or “mind control” to impair critical thinking.

Michael Langone, executive director of the International Cultic Studies Association, defines a destructive cult as “a highly manipulative group which exploits and sometimes physically and/or psychologically damages members and recruits.” Eli Shapiro, in *Cults and the Family*, describes “destructive cultism” as a “sociopathic syndrome.” He highlights alarming qualities like “behavioral and personality changes, loss of personal identity, estrangement from family… and pronounced mental control and enslavement by cult leaders.”

However, scholars often criticize this “destructive cult” label as overgeneralized. John A. Saliba, in *Understanding New Religious Movements*, argues its use can unfairly imply other groups will commit extreme acts, like the mass suicide at Peoples Temple, seen as the “paradigm of a destructive cult.” This illustrates the label’s contentious nature.

9. **The End Is Nigh (or Is It?): Doomsday Cults**

Some groups take beliefs to an extreme, predicting or even attempting a dramatic, often catastrophic, world transformation. These “doomsday cults” feature apocalypticism and millenarianism – prophecies about an era’s end or a thousand-year period of significant change.

In the 1950s, Leon Festinger and colleagues studied the Seekers, a UFO religion whose leader prophesied world destruction. Their findings in *When Prophecy Fails* offered rare insights into belief dynamics when the prophecy failed.

Doomsday cults drew intense media attention in the late 1980s, often portrayed as serious societal threats. A 1997 psychological study by Festinger, Riecken, and Schachter suggested people sometimes turn to a “cataclysmic world view” after failing to find meaning in mainstream movements. Extreme visions can offer appealing answers when conventional paths fall short.

10. **Power Plays: The Rise of Political Cults**

Cult dynamics aren’t exclusive to religious groups; they can manifest politically. A “political cult” refers to groups primarily interested in political action and ideology, often pushing boundaries with an almost religious fervor for specific goals.

Journalists and scholars have observed these groups, particularly those with far-left or far-right agendas. They often coalesce around a charismatic leader demanding absolute loyalty and adherence to a specific, fervent worldview, echoing religious cult characteristics.

Dennis Tourish and Tim Wohlforth explored this in their 2000 book, *On the Edge: Political Cults Right and Left*, examining a dozen organizations in the US and Great Britain. Their work reveals how readily intense devotion and control can permeate civic life, demonstrating that extreme group dynamics aren’t limited to the spiritual realm.

11. **Standing Against the Tide: The Christian Countercult Movement**

As new religious groups emerged, some established Christian denominations responded by forming the “Christian countercult movement” in the 1940s. These evangelicals actively identify and oppose non-Christian religions and any Christian sects deemed “heretical” or “counterfeit,” particularly those deviating from Christian orthodoxy and biblical inerrancy.

For this movement, groups claiming Christianity but with diverging teachings are labeled cults. They also scrutinize non-Christian religions like Hinduism if perceived as problematic from their theological perspective.

A core mission of the Christian countercult movement is evangelism. Activist writers emphasize evangelizing followers of “cults,” aiming to guide individuals they believe have gone astray back into what they consider true Christianity. This proactive approach stems from deep convictions about spiritual truth.

12. **Fighting for Freedom (or Control?): The Secular Anti-Cult Movement**

A different opposition arose in the late 1960s: the “secular anti-cult movement” (ACM), fueled by new religions and tragic events like Jonestown. ACM organizations advocated for relatives of “cult” converts, believing their loved ones had not acted of their own free will.

This led psychologists and sociologists to suggest “brainwashing” techniques maintained loyalty, spawning controversial “deprogramming” attempts. In mass media, “cult” became a heavily loaded term, associated with kidnapping, abuse, criminal activity, and mass suicide.

While a small minority of new religious groups *have* been involved in horrific activities, mass culture often unfairly extends these negative qualities to *any* culturally deviant group. Most sociologists eventually abandoned brainwashing theories by the late 1980s, viewing conversion as “an act of rational choice,” albeit influenced by psychological mechanisms.

13. **When Governments Get Involved: Policies and Legal Challenges**

Governmental intervention adds complexity. “Cult” or “sect” labels in official documents reflect popular, negative connotations, a practice sociologists criticize for potentially infringing religious freedoms.

During the 1990s counter-cult movement, some governments published “lists of cults.” These labeled groups, found globally, vary from small local gatherings to international organizations. Yet, criteria for these lists were inconsistent, and many governments avoided such terminology.

Since the 2000s, some governments have distanced themselves from rigid classifications, though responses remain mixed. Some align with critics, distinguishing “legitimate” religions from “dangerous,” “unwanted” cults in public policy. This highlights ongoing challenges in regulating religious expression.

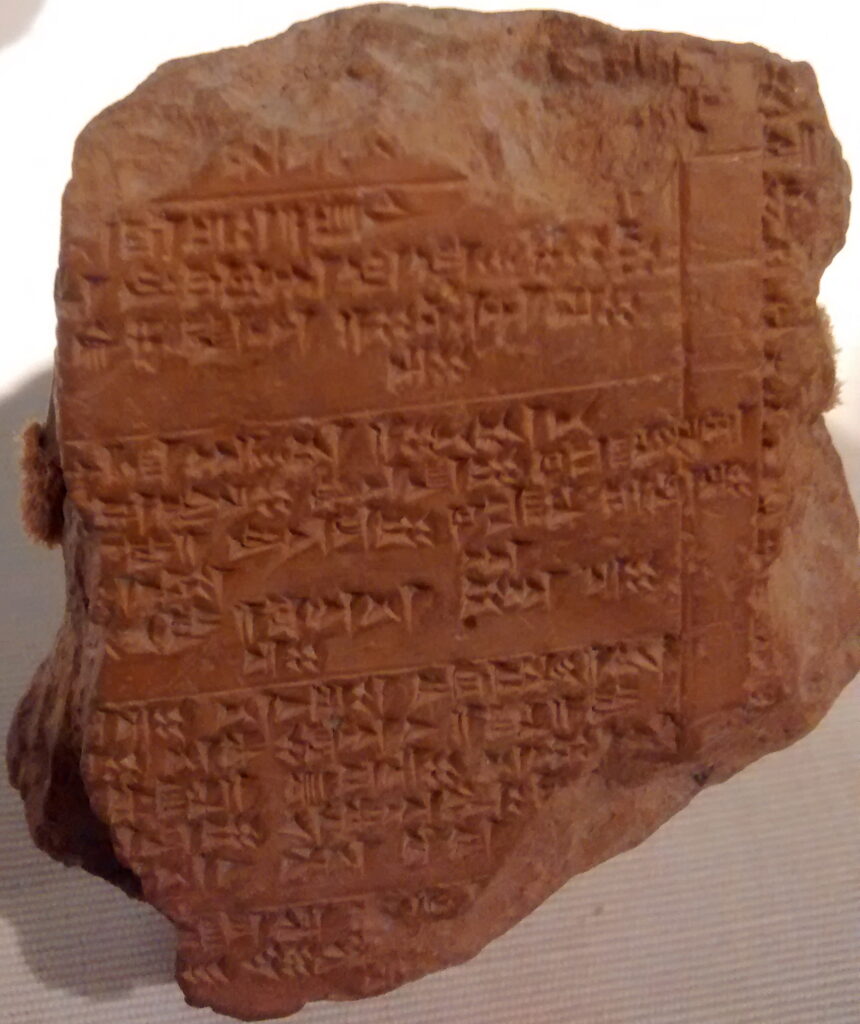

14. **From Imperial China to Falun Gong: China’s “Xiejiao”**

China’s history includes classifying religions as *xiéjiào* (邪教), or “evil cults.” Historically, this wasn’t about the truth of beliefs, but about state authorization and perceived challenges to state legitimacy. Groups branded *xiejiao* faced severe suppression and punishment.

This demonstrates how governments can wield labels to control religious expression. In modern China, Falun Gong, an ultra-conservative new religious movement headquartered in New York, is a prominent example of a *xiejiao* that has faced intense suppression.

This classification powerfully showcases the deep entanglement of religion, state power, and societal control, with significant consequences for groups deemed outside the accepted norm.

15. **Global Crackdowns and Protections: Russia, US, and Western Europe**

Governmental responses to cults vary widely. In Russia, the Interior Ministry’s 2008 list of “extremist groups” included Islamic groups outside “traditional Islam” and “Pagan cults.” In 2009, a Ministry of Justice council listed 80 “potentially dangerous” large sects, including groups like The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and Jehovah’s Witnesses.

In the United States, 1970s debates over “brainwashing theory” in court cases to justify “deprogramming” saw sociologists often defending new religious movements. A landmark 1990 court case, *United States v. Fishman*, ended the use of brainwashing theories by expert witnesses, citing the *Frye standard*. While religious activities are First Amendment-protected, no members are immune from criminal prosecution.

Western European approaches differed. France and Belgium accepted “brainwashing” theories, leading to interventionist policies. Nations like Sweden and Italy were more cautious. The Solar Temple mass murder/suicides contributed to Europe’s anti-cult stances, and concerns even arose that anti-cult laws could affect groups *within* the Roman Catholic Church. This illustrates policy and perception’s complex interplay.

**The Unending Quest for Understanding**

Phew! What a journey, right? We started with “worship” and navigated academic debates to governmental crackdowns. “Cult” isn’t just a simple label; it’s a loaded term sparking intense discussions, raising profound questions about belief, community, and control, reflecting the fascinating, sometimes frightening, diversity of human social organization.

From nuanced sociological classifications to emotionally charged controversies and diverse governmental responses, it’s a field that continues to evolve. Understanding these complex social groups requires more than a snappy headline. It demands curiosity, critical thinking, and a recognition of the incredibly human need for belonging, purpose, and sometimes, something radically new. So, keep questioning, keep learning, and keep engaging with the captivating, often challenging, world around us!