The Middle East is a region often misunderstood, its complexities frequently reduced to soundbites. Yet, beneath the surface of geopolitical narratives lies a vibrant, ancient, and deeply interwoven tapestry of faiths, each contributing unique threads to the region’s rich cultural and historical fabric. For millennia, this land has been a crucible of spiritual innovation, giving birth to some of the world’s most enduring belief systems and fostering a diversity of traditions that continue to shape lives and landscapes.

From the bustling streets of Cairo to the historic cities of Iran, and across the diverse plains of the Levant, religious practice is not merely a personal conviction but a cornerstone of identity, community, and heritage. Understanding these faiths is not just an academic exercise; it is key to appreciating the depth and dynamism of Middle Eastern societies, offering insights into their past, present, and future. It’s about recognizing the commonalities that bind and the distinctions that define, all within a narrative steeped in profound spiritual significance.

In this comprehensive exploration, we embark on a journey through the major religious communities that call the Middle East home. We’ll delve into their origins, their tenets, their historical roles, and their contemporary presence, uncovering the remarkable array of beliefs that coexist and sometimes intersect in this pivotal part of the world. Join us as we unpack the layers of devotion, tradition, and community that form the spiritual bedrock of the Middle East, moving “Beyond the Headlines” to truly appreciate its vibrant mosaic of faiths and traditions.

1. **Islam: The Dominant Faith**Islam stands as the most widely followed religion throughout the Middle East, a powerful force that has shaped the region’s cultural, social, and political landscape for centuries. Emerging in Arabia in the 7th century CE, it rapidly spread, becoming the dominant religion in nearly every Middle Eastern country today. Approximately 91.17% of the people in the Middle East are Muslim, and about 20% of the world’s total Muslim population resides within this historically significant region.

At its heart, Islam is a monotheistic religion, firmly teaching belief in one God, referred to as Allah. Its foundational text, the Quran, serves as the central religious scripture, believed by Muslims to be the word of God revealed to the Prophet Muhammad. Muslims hold that Muhammad is the final prophet in a long lineage of divine messengers, a chain that stretches from Adam through figures like John the Baptist and Jesus, culminating in Muhammad himself. This belief in a singular, omnipotent deity and the finality of Muhammad’s prophethood are core tenets universally accepted across its diverse branches.

The vast majority of Muslims globally and within the Middle East adhere to either the Sunni or Shi’a branches, which, despite sharing fundamental beliefs and the teachings of the Quran, have distinct historical origins in their leadership succession after the Prophet Muhammad’s death. Beyond these two major sects, smaller groups such as Ibadism, Sufism, and non-denominational forms also exist, as does the Ahmadiyya. However, it is important to note that Ahmadis are considered heretical by the majority of Muslims, highlighting some of the nuanced theological distinctions within the broader Islamic faith.

The profound influence of Islam on the Middle East is undeniable, extending far beyond religious practice to inform legal systems, artistic expression, philosophical thought, and daily life. Its principles of community, justice, and devotion have left an indelible mark, shaping the region’s identity and its interactions with the wider world. Understanding Islam is therefore fundamental to grasping the essence of the Middle East.

Read more about: The Archangel Michael: An Enduring Saga of Divine Roles and Reverence Across Abrahamic Faiths

2. **Sunni Islam: The Majority Branch**Sunni Islam represents the largest branch of Islam, not only globally but also within most countries of the Middle East, constituting the overwhelming majority of Muslims in many nations across the region. According to Sunni traditions, Muhammad left no explicit successor, leading to the appointment of Abu Bakr as the first caliph by the participants of the Saqifah event. This historical event and the subsequent caliphate lineage distinguish Sunni Islam from other branches that hold differing views on the rightful spiritual and political leadership after the Prophet Muhammad.

The legal and theological framework of Sunni Islam is primarily based on the Quran, alongside the Hadith, which are collections of sayings and actions attributed to the Prophet Muhammad. Specifically, the Kutub al-Sittah, six major collections of Hadith, are highly revered and form a crucial basis for traditional jurisprudence. In conjunction with binding juristic consensus, these sources provide the foundation for Sharia rulings within Sunni Islam.

Sunni jurisprudence also incorporates other principles such as analogical reasoning, consideration of public welfare, and juristic discretion, all developed within the framework of traditional legal schools. In terms of creed, the Sunni tradition upholds the six pillars of imān, or faith. The Ash’ari and Maturidi schools of Kalam, a form of scholastic theology, as well as the textualist school known as traditionalist theology, are prominent in matters of doctrine, illustrating the intellectual depth and diversity of Sunni thought.

This widespread adherence to Sunni Islam has naturally led to its significant cultural and social imprint across the Middle East. Its interpretations of religious law and tradition have historically guided societal norms, governance, and individual practice in numerous countries, fostering a collective identity rooted in its specific theological and historical understandings, and shaping the region’s societal fabric.

3. **Shia Islam: Its Diverse Branches**Shia Islam, or Shīʿīsm, stands as the second-largest branch of Islam, representing a significant and historically influential community, particularly within the Middle East. The fundamental schism between Shi’as and Sunnis occurred shortly after the death of Muhammad, stemming from a disagreement over who should succeed the Prophet as the leader of the Muslim community. While members of the ‘ummah’ who later became Sunni preferred Abu Bakr, representatives of the Shi’ita branch preferred Ali ibn Abi Talib, Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law, as the rightful ruler. This foundational divergence led to significant historical events, such as the Battle of Siffin and the Battle of Karbala, which deepened the divide and cemented the distinct identities of the two sects.

Modern Shia Islam is broadly categorized into three main groupings: Twelvers, Ismailis, and Zaidis. Among these, the Twelvers constitute the largest and most influential group, making up perhaps 85 percent of all Shias. They hold significant populations in the Middle East, notably in Iran, where 75% of the population is Twelver Shia, and in Iraq, with 45%. Other countries with notable Twelver Shia populations include Bahrain (35-40%), Kuwait (15%), Yemen (30%), Syria (12.5%), Lebanon (20%), Saudi Arabia (8%), Oman (6%), UAE (5%), and Turkey (12.5%), among others.

Over the centuries, other differences have emerged between Sunni and Shia practices, beliefs, and cultural expressions, beyond the initial question of succession. These distinctions, while sometimes subtle, have contributed to varying interpretations of Islamic law, religious rituals, and community structures. Many conflicts between the two communities have occurred throughout history. The historical and ongoing dynamic between Sunni and Shia communities remains a pivotal aspect of religious and political life in several Middle Eastern nations.

Understanding the unique theological perspectives and historical trajectory of Shia Islam, particularly its Twelver majority and its diverse sub-sects, is crucial for appreciating the intricate religious landscape of the Middle East. It highlights a rich tradition of scholarship, devotion, and a distinct lineage of spiritual authority that continues to resonate powerfully throughout the region.

4. **Zaydi Shi’a: A Unique Yemeni Tradition**Among the various branches of Shia Islam, Zaydi Shi’a represents a distinct and historically significant group, particularly prominent in Yemen. Followers of the Zaydi Islamic jurisprudence are called Zaydi Shi’a and constitute approximately 30% of the Muslim population in Yemen. This sect emerged in the eighth century, out of Shi’a Islam, and holds a unique position within the Islamic theological spectrum.

The Zaydis are named after Zayd ibn ʻAlī, the grandson of Husayn ibn ʻAlī, whom they recognize as the fifth Imam. Their theological and legal interpretations differ from other Shia branches, particularly the Twelvers, primarily regarding the lineage of Imams and certain aspects of jurisprudence. This historical divergence led to the formation of a distinct school of thought, which has maintained its identity and influence over centuries.

The presence of Zaydi Shi’a in Yemen underscores the diverse tapestry of Islamic practice even within a single country in the Middle East. Their historical and ongoing role in Yemeni society has been profound, shaping political dynamics, cultural practices, and religious life in the northern parts of the country. This tradition represents an important strand of Islamic history, showcasing the enduring capacity for unique theological development within the wider faith, contributing to the rich pluralism of the region.

5. **Alawites: A Syncretic Syrian Sect**Alawites, also rendered as Alawīyyah or Nusạyriyya, are a distinctive syncretic sect that falls under the broader umbrella of the Twelver branch of Shia Islam. Primarily centered in Syria, this community holds a significant demographic and political presence in the country. The eponymously named Alawites revere Ali (Ali ibn Abi Talib), considered the 1st Imam of the Twelver school. However, their unique theological interpretations often lead them to be considered Ghulat, or ‘extremists,’ by most other sects of Shia Islam, highlighting their distinctiveness.

The sect is believed to have been founded by Ibn Nusayr during the 9th century and fully established as a religion. This historical origin is why Alawites are sometimes referred to as Nusayris, although this term has, in modern times, acquired a pejorative connotation. Another name, Ansari, is thought to be a mistransliteration of Nusayri, underscoring the historical ambiguity and external interpretations surrounding their identity.

Alawites have historically maintained a degree of secrecy regarding their beliefs, particularly from outsiders and non-initiated members. At the core of Alawite belief is a divine triad, which comprises three aspects of the one God, a concept that further distinguishes them from mainstream Islamic monotheism. They have traditionally inhabited the An-Nusayriyah Mountains along Syria’s Mediterranean coast, with Latakia and Tartus serving as principal cities, and are also concentrated in the plains around Hama and Homs.

Today, Alawites represent an estimated 11 percent of the Syrian population, numbering around 2.6 million out of a total population of 22 million. They are also a notable minority in Turkey and northern Lebanon, and a small population resides in the village of Ghajar in the Golan Heights. In Syria, Alawites form the dominant religious group along the coast and in coastal towns, living alongside Sunnis, Christians, and Ismailis, demonstrating the intricate intercommunal dynamics of the region.

6. **Alevism: A Unique Turkish Form of Islam**Alevism represents a small yet significant syncretic and heterodox form of Islam, primarily found among ethnic Turks and Kurds in Turkey. This unique faith tradition blends elements from Shia, Sufi, Sunni, and local traditions, creating a spiritual path that is distinct from mainstream Islamic practice. Adherents of Alevism follow the mystical (bāṭenī) teachings of Ali, the Twelve Imams, and especially the revered 13th-century Alevi saint, Haji Bektash Veli, emphasizing an internal, spiritual journey.

Estimates place the Alevi population between 8 and 12 million, making them one of the largest branches of Islam in Turkey after the majority Sunni Islam, comprising between 10% and 15% of the country’s total population. Their spiritual centers are not traditional mosques but rather “cemevi” halls, which serve as gathering places for worship ceremonies. These ceremonies are notably characterized by the inclusion of wine, music and dancing, and both women and men participate together, a significant departure from many mainstream Islamic practices.

Further distinguishing Alevism are its unique ritual observances. Alevis typically do not observe the five daily salat prayers or prostrations in the same manner as mainstream Muslims; they only bow twice in the presence of their spiritual leader. They also do not observe Ramadan in the traditional sense, nor the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, considering a true pilgrimage to be an internal, spiritual one. While Alevis share some links with Twelver Shia Islam, such as the importance of the Ahl al-Bayt, the day of Ashura, and the Mourning of Muharram commemorating Karbala, they do not follow “taqlid” (emulation) towards a Marja’ (source of emulation). Many Alevi practices are also influenced by Sufi elements of the Bektashi tariqa, further highlighting their rich syncretic nature.

Alevism’s distinctive blend of traditions and practices underscores the vast diversity within Islam, demonstrating how local cultures and mystical interpretations can lead to unique expressions of faith. Their enduring presence and unique customs offer valuable insight into the pluralistic religious landscape of the Middle East, particularly within Turkey, enriching the region’s spiritual heritage.

7. **Christianity: An Ancient and Diverse Presence**Christianity, a religion with deep roots in the Middle East, originated in the region in the 1st century AD. For several centuries, it stood as one of the major religions until the Muslim conquests of the mid-to-late 7th century AD. The Christian communities in the Middle East are renowned for their remarkable diversity in beliefs and traditions, presenting a stark contrast to the more monolithic perceptions often held in other parts of the world. This rich tapestry of denominations, rites, and cultures is a testament to its long and complex history within this pivotal geographical area.

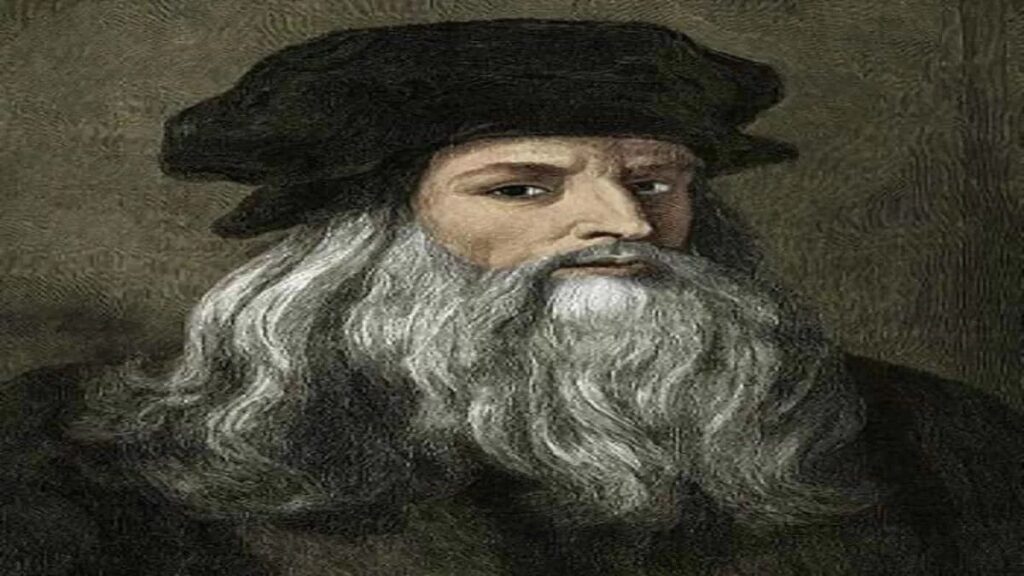

Throughout history, Christian communities have played an indispensable and vital role in the social, intellectual, and cultural development of the Middle East. Scholars and intellectuals agree that Christians in the Middle East have made significant contributions to Arab and Islamic civilization since the introduction of Islam. They have profoundly impacted the culture of the Mashriq (the Arab East), Turkey, and Iran, serving as crucial bridges of knowledge, art, and intellectual exchange, and leaving an enduring legacy in various fields, from medicine to philosophy.

However, the Christian population in the Middle East has experienced a notable decline over the past century. From comprising 20% of the population in the early 20th century, Christians now make up approximately 5%. This demographic shift is largely attributed to factors such as extensive emigration, as many have sought security and stability outside their homelands due to political turmoil. These challenges have pressed indigenous Near Eastern Christians of various ethnicities towards seeking security and stability outside their homelands, impacting the size and vibrancy of long-established communities.

Presently, Cyprus stands as the only Christian-majority country in the Middle East, reflecting the broader demographic changes across the region. Despite these shifts, the various Christian denominations—including Orthodox, Catholic, and Protestant traditions, alongside ancient Eastern churches—continue to maintain a presence, often as resilient minorities who actively preserve their unique spiritual and cultural heritages, contributing to the enduring diversity of the Middle Eastern religious landscape. Middle Eastern Christians are also noted as being relatively wealthy, well educated, and politically moderate, playing an active role in various social, economical, sporting, and political aspects in the Middle East.

8. **Coptic Orthodox Christians: Egypt’s Enduring Faith**The largest Christian group in the Middle East is the Coptic Orthodox Christian population, an Egyptian ethnoreligious community that originally spoke Coptic but is now Arabic-speaking. This community is a vibrant and deeply rooted part of Egypt’s fabric, with official census figures citing 6–11 million people in the past decade, though Coptic sources suggest figures closer to 15–20 million. Their presence is primarily concentrated in Egypt, with smaller communities also found in Sudan, Libya, Israel, Cyprus, and Jordan, showcasing their historical reach.

Copts have historically demonstrated a strong socio-economic standing within Egypt. They tend to have relatively higher educational attainment, a comparatively higher wealth index, and a stronger representation in white-collar job types. Historically, many Copts were accountants, and in 1961, Coptic Christians owned a significant 51% of Egyptian banks. According to scholar Andrea Rugh, Copts tend to belong to the educated middle and upper-middle class, while scholar Lois Farag noted that “The Copts still played the major role in managing Egypt’s state finances. They held 20% of total state capital, 45% of government employment, and 45% of government salarie.”

Despite these historical contributions and current achievements, Copts face certain challenges, including limited representation in security agencies. There is a degree of tension between Muslims and Copts in Egypt, with Copts advocating for greater representation in government and reduced legal and administrative discrimination. The modernization of media and the liberalization of the Egyptian press in the 2000s have brought Coptic Christianity to the forefront of religious discussions, sometimes exacerbating sectarian tensions due to the publicizing of extremist views from minorities within both religious communities.

Nonetheless, the Coptic Orthodox Christian community remains a steadfast and integral part of the Middle East’s religious mosaic. Their enduring faith, rich history, and significant cultural contributions continue to shape the spiritual and social landscape of Egypt and beyond. Their resilience in maintaining their distinct identity and traditions, despite societal pressures, highlights the deep historical layers of religious life in the region.

Continuing our journey through the Middle East’s rich spiritual tapestry, we now turn our attention to other significant Abrahamic traditions and then venture into ancient non-Abrahamic faiths that have profoundly shaped the region. From resilient Christian communities to the enduring legacy of Judaism and the distinct doctrines of esoteric groups, this section unveils more layers of the Middle East’s diverse religious landscape, showcasing the profound depth of its spiritual heritage.

9. **Maronites: Lebanon’s Enduring Christian Community**Among the prominent Christian groups in the Middle East, the Arabic-speaking Maronites stand out, primarily concentrated in Lebanon, with significant communities also found in Syria, Israel, and Cyprus. Numbering between 1.1 and 1.2 million across the region, they represent a pivotal ethnoreligious community. Their historical influence in Lebanon is so profound that, under the terms of the informal National Pact, the country’s president must always be a Maronite Christian.

This unique political arrangement underscores the deep integration of the Maronite community into Lebanon’s national identity and governance. Beyond the presidency, Christians in Lebanon, including Maronites, hold 50% of the Parliament’s representation and play active roles across media, politics, entertainment, and banking sectors, both within Lebanon and globally. This enduring presence reflects a community that has not only persevered but thrived, contributing significantly to the social and economic fabric of their homelands.

The Maronites’ history is one of resilience and distinct cultural preservation. They are Eastern Catholics of the Syriac tradition, maintaining a strong connection to their ancient liturgical practices and Aramaic heritage, even as they are now primarily Arabic-speaking. Their steadfast adherence to their faith and traditions, often amidst complex regional dynamics, makes them a vital thread in the Middle East’s intricate mosaic of beliefs, embodying a unique blend of historical depth and contemporary relevance.

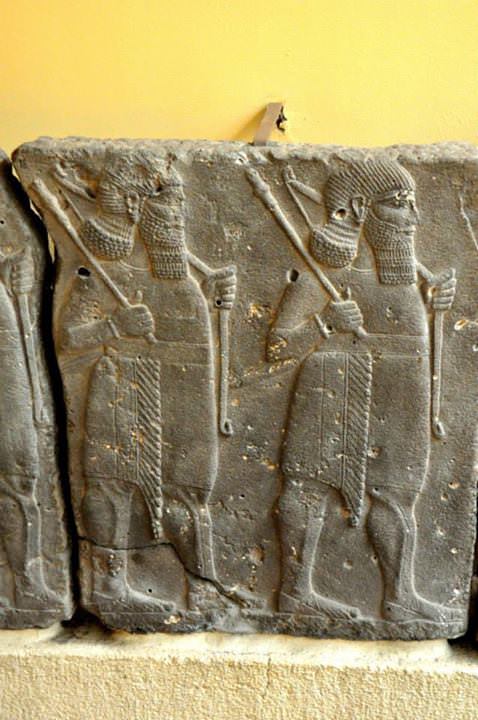

10. **Assyrians: Guardians of Ancient Aramaic Heritage**The Assyrians represent another deeply rooted Christian ethnoreligious group in the Middle East, indigenous to historical lands encompassing Iraq, southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, and northeastern Syria. These Eastern Aramaic-speaking people are direct descendants of ancient Mesopotamian civilizations, carrying a heritage that spans millennia. Their presence is a testament to the remarkable continuity of some of the region’s earliest Christian communities.

However, the Assyrian community has faced immense challenges, including severe ethnic and religious persecution over the centuries, notably the Assyrian genocide and the Simele massacre. These historical traumas have led to significant diaspora, with many fleeing to the West or consolidating in specific areas within the Middle East. Despite these adversities, they have maintained their distinct cultural and linguistic identity, with Syriac Christian communities, a mix of Neo-Aramaic speaking Assyrians and other Arabic-speaking Christian groups, still numbering between 877,000 and 1,139,000 in Syria alone.

In Iraq, the numbers of indigenous Assyrians have declined to around 140,000, yet they remain a resilient community striving to preserve their unique religious and cultural practices. Their enduring presence, despite persecution and displacement, highlights the strength of their faith and their determination to safeguard a heritage deeply interwoven with the very origins of Christianity in the region, serving as living links to an ancient past.

11. **Judaism: An Ancient Faith’s Modern Presence**Judaism, one of the three major Abrahamic religions, has an ancient and profound history throughout the Middle East, where a large portion of Jewish people resided for over 2,000 years. These communities, colloquially known as Mizrahi Jews, include descendants from diverse areas such as Babylonia, Morocco, Egypt, Syria, Iran, and Yemen, among others. Their traditions and customs bear strong influences from the Muslim and broader Middle Eastern cultures with which they coexisted for centuries.

A significant demographic shift occurred since the 1950s, largely driven by growing antisemitism, leading most of these Jewish communities to emigrate to Israel. Today, Mizrahi Jews constitute the majority of Israel’s Jewish population and roughly a third of total world Jews, marking a dramatic change in their geographical distribution. While their numbers in other Middle Eastern countries are now small and scattered, their historical impact remains indelible.

Presently, Israel is the primary center of Jewish life in the Middle East, with its population being 75.3% Jewish. This nation stands as a beacon for the enduring legacy of Judaism, which originated in the Levant in the 6th century BCE. The faith continues to flourish, with its ancient spiritual practices, rich cultural expressions, and deep historical ties to the land, representing a cornerstone of the region’s diverse religious identity and its foundational Abrahamic heritage.

12. **Druzism: A Unique Esoteric Faith of the Levant**Druzism stands as one of the major religious groups in the Levant, an esoteric monotheistic faith that developed from Isma’ilism but whose adherents do not identify as Muslims. With between 800,000 and a million adherents, Druze communities are predominantly located in Lebanon, Syria, and Israel, with smaller numbers in Jordan. They form significant percentages of the population in these countries, notably 5.5% in Lebanon, 3% in Syria, and 1.6% in Israel.

The oldest and most densely populated Druze communities are found in Mount Lebanon and in the south of Syria around Jabal al-Druze, literally “the Mountain of the Druze.” While originating from Isma’ilite teachings, Druzism incorporates a fascinating blend of elements from Jewish, Christian, Gnostic, Neoplatonic, and Iranian traditions, creating a deeply spiritual and distinct theological system. Their beliefs are often kept secret from outsiders, fostering a strong sense of internal community and identity.

Druze maintain their Arabic language and culture as integral parts of their identity, showcasing a unique synthesis of regional heritage and distinct spiritual practice. Their resilience and ability to preserve their faith and community structures, often in challenging political landscapes, highlight the profound diversity of belief systems that coexist in the Middle East, making Druzism a captivating example of the region’s rich religious pluralism.

13. **Baháʼí Faith: A Global Message from Middle Eastern Origins**The Baháʼí Faith is a relatively new religion, established by Baháʼu’lláh in 19th-century Iran, with its roots deeply embedded in the Middle East. Teaching the essential worth of all religions and the fundamental unity of all people, it offers a modern global message of peace and reconciliation. Despite its profound and inclusive teachings, the Baháʼí community has faced ongoing persecution since its inception in its region of origin.

Central to Baháʼí teachings is the belief that religion is revealed progressively by a single God through “Manifestations of God,” figures like Buddha, Jesus, and Muhammad, with the Báb and Baháʼu’lláh being the most recent. This perspective views major religions as unified in purpose, differing only in social practices and interpretations, emphasizing a harmonious understanding of spiritual truth. The faith explicitly rejects racism, sexism, and nationalism, advocating for a unified world order that ensures the prosperity of all.

With an estimated 7 to 8 million followers worldwide, the Baháʼí Faith has a noteworthy presence in Iran, Yemen, United Arab Emirates, Palestine, Israel, and Turkey. Its international headquarters are symbolically located on the northern slope of Mount Carmel in Haifa, Israel, serving as a spiritual and administrative center for its global community. This faith represents a powerful modern expression of spirituality that emerged from the Middle East, offering a vision of global unity and understanding.

14. **Zoroastrianism: Persia’s Ancient Monotheistic Legacy**Venturing into the non-Abrahamic traditions, Zoroastrianism stands as one of the world’s oldest monotheistic religions, founded approximately 3,500 years ago. Its origins are deeply intertwined with ancient Persia, and for about a millennium, it was one of the most powerful religions globally, particularly during the Persian pre-Islamic dynasties. Today, it maintains a small but significant presence in central Iran, with fewer than 20,000 adherents remaining in the country.

At its core, Zoroastrianism centers on the supreme deity Ahura Mazda, the lord of wisdom, symbolized by the light of the sun and fire. It embodies a dualistic principle of Spenta Mainyu (creative mind or goodness) and Angra Mainyu (destructive mind or evil), known as Ahriman in Middle Persian. This philosophy posits that individuals have the free will to choose between these two paths, emphasizing moral choice and responsibility in life, as guided by their primary sacred text, the Avesta.

Despite now being one of the smallest religions worldwide, with only 190,000 followers globally, Zoroastrianism’s ancient heritage profoundly influenced later monotheistic traditions, including Abrahamic faiths. Its enduring presence in the Middle East, particularly in Iran, represents a living link to the region’s ancient spiritual roots, enriching the broader tapestry of its religious history with its unique theological depth and ethical framework. It serves as a powerful reminder of the diverse and ancient spiritual currents that have flowed through this historic land.

**Beyond the Headlines: A Tapestry of Faiths**

As we conclude our extensive exploration of the Middle East’s religious landscape, it becomes abundantly clear that this region is far more than the headlines often portray. It is a vibrant, living tapestry woven from millennia of spiritual devotion, intellectual inquiry, and communal resilience. From the dominant currents of Islam and Christianity to the distinct streams of Judaism, Druzism, Baháʼí Faith, and Zoroastrianism, each tradition contributes an invaluable thread to a narrative of unparalleled depth and diversity.

These faiths, with their unique histories, practices, and perspectives, not only define individual and community identities but also collectively shape the region’s cultural, social, and political contours. Understanding them allows us to move beyond simplistic narratives, appreciating the intricate interconnections and rich pluralism that have always characterized this cradle of civilizations. The Middle East, in its profound spiritual diversity, continues to be a testament to humanity’s enduring quest for meaning and connection, inviting us all to look closer and discover its true, multifaceted essence.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/061125-Dolly-Parton-Summer-d491337e1d9c4023bcf0ab42aafff3ea.jpg)