Marilyn Monroe, born Norma Jeane Mortenson, remains an indelible figure in the annals of American cinema and popular culture, a symbol whose luminescence has only intensified in the decades since her untimely passing at the age of 36. Her life, a complex tapestry woven with threads of vulnerability, ambition, and extraordinary talent, continues to captivate and provoke discussion, far beyond the ‘blonde bombshell’ image that first catapulted her to global fame. This article aims to delve deeply into the formative experiences and pivotal career moments that shaped one of Hollywood’s most enduring legends, meticulously drawing from the available historical record.

From a challenging childhood marked by instability and the relentless pursuit of artistic credibility, Monroe navigated a treacherous path through an industry often eager to typecast and exploit. Her journey from the assembly line to the silver screen, through highly publicized marriages and groundbreaking battles for professional autonomy, illustrates a resilience often overshadowed by the narratives surrounding her personal struggles. Understanding her story requires an examination of the precise junctures where her personal history intersected with her public persona, revealing the depth beneath the glamorous surface.

What emerges from a comprehensive review of her life is not merely the story of a sex symbol, but of a woman who, despite immense personal obstacles and systemic pressures, strove for control over her craft and her image. Her impact reverberated through her era and continues to shape contemporary perceptions of stardom, ambition, and the human cost of immense fame. Let us embark on an in-depth exploration of the key facets that defined Marilyn Monroe’s remarkable, albeit tragically short, life and career, ensuring that her complex legacy is viewed through a lens of objective factual reporting.

1. **Early Life and Formative Years: The Foundations of a Star**Marilyn Monroe’s journey began not in the glittering lights of Hollywood, but in a childhood marked by profound instability and emotional hardship. Born Norma Jeane Mortenson at Los Angeles General Hospital on June 1, 1926, her early years were largely spent moving between foster homes and an orphanage, a stark contrast to the glamorous image she would later embody. Her mother, Gladys Pearl Baker, was mentally and financially unprepared for a child, having a complex personal history including a prior abusive marriage and the kidnapping of her two older children.

Gladys, who worked as a film negative cutter, eventually suffered a mental breakdown in January 1934, leading to a diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia and subsequent commitment to a state hospital. This left seven-year-old Monroe a ward of the state, with her mother’s friend, Grace Goddard, taking responsibility for her affairs. This period was fraught with difficulty, including a potential experience of sexual abuse during her stay with the Atkinsons, and alleged molestation during a second brief stay with Grace and Erwin “Doc” Goddard.

These early traumas contributed to a shy demeanor, the development of a stutter, and a tendency to withdraw. However, it was also during this tumultuous time that her aspirations for acting began to take root. Monroe later articulated her motivation, stating, “I didn’t like the world around me because it was kind of grim … When I heard that this was acting, I said that’s what I want to be … Some of my foster families used to send me to the movies to get me out of the house and there I’d sit all day and way into the night. Up in front, there with the screen so big, a little kid all alone, and I loved it.” This early fascination with cinema offered an escape and planted the seeds for her future career, providing a profound insight into the origins of her ambition.

Her education at Emerson Junior High School saw her excel in writing and contribute to the school newspaper, though she was otherwise a mediocre student. Facing the prospect of returning to the orphanage when her foster family, the Goddards, had to relocate out of state due to Doc’s employment, she made a pivotal decision. To circumvent California child protection laws, it was decided that she would leave high school and marry their neighbor, factory worker James Dougherty, who was five years her senior. The marriage took place shortly after her 16th birthday on June 19, 1942, a pragmatic decision born of necessity rather than romance, a circumstance Monroe would later describe with a sense of “dying of boredom.”

Read more about: Joan Plowright, an Era-Defining Actress of Dazzling Versatility, Dies at 95: A Retrospective on a Seven-Decade Career

2. **From Factory Worker to Pin-Up Model: The Genesis of an Icon**With her husband, James Dougherty, deployed to the Pacific in April 1944 as part of the Merchant Marine during World War II, Monroe moved in with his parents and took a job at the Radioplane Company, a munitions factory in Van Nuys, contributing to the war effort. It was in this unexpected setting that a chance encounter would fundamentally alter the trajectory of her life. In late 1944, photographer David Conover, working for the U.S. Army Air Forces’ First Motion Picture Unit, visited the factory to capture morale-boosting images of female workers.

Although none of the photographs featuring Monroe were ultimately used, the experience ignited a new path. By January 1945, she had left her factory job and embarked on a modeling career, working for Conover and his associates. This decision, made in defiance of her deployed husband and his disapproving mother, led her to sign a contract with the Blue Book Model Agency in August 1945, marking her official entry into the professional modeling world. The agency quickly recognized her potential, albeit steering her towards pin-up rather than high fashion, a genre better suited to her developing figure.

During this period, she underwent a significant transformation of her public image, straightening her naturally curly brown hair and dyeing it the iconic platinum blonde that would become synonymous with her persona. Emmeline Snively, the owner of the Blue Book Model Agency, observed Monroe’s ambition and diligence, noting that by early 1946, she had graced the covers of 33 magazines, including prominent publications such as *Pageant*, *U.S. Camera*, *Laff*, and *Peek*. Occasionally employing the pseudonym Jean Norman, she rapidly ascended as one of the agency’s most sought-after models.

Her burgeoning success as a pin-up model laid the groundwork for her transition into acting. The visual appeal and public recognition she garnered through her modeling assignments were undeniable assets. It was through Snively’s connections that Monroe secured a contract with an acting agency in June 1946, setting the stage for her next crucial step toward Hollywood stardom. This phase of her life illustrates a determined young woman, seizing opportunities and actively shaping her outward presentation to align with her aspirations.

3. **Navigating Early Hollywood: First Contracts and a New Name**Monroe’s initial foray into the studio system was not without its challenges. After an unsuccessful interview at Paramount Pictures, she secured a screen-test arranged by Ben Lyon, a 20th Century-Fox executive. Despite head executive Darryl F. Zanuck’s initial lack of enthusiasm, Fox offered her a standard six-month contract in August 1946, primarily to prevent her from being signed by rival studio RKO Pictures. It was during this period that she adopted the stage name that would become world-renowned: “Marilyn Monroe.” Ben Lyon selected “Marilyn,” reportedly reminded of Broadway star Marilyn Miller, while “Monroe” was her mother’s maiden name.

This fresh start also coincided with a significant personal decision. In September 1946, she divorced James Dougherty, who had expressed opposition to her burgeoning career. The period that followed was dedicated to intensive preparation; Monroe spent her first six months at Fox diligently learning acting, singing, and dancing, alongside observing the intricate processes of film-making. Her dedication paid off, leading to a contract renewal in February 1947 and her first minor film roles in *Dangerous Years* (1947) and *Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay!* (1948).

Beyond her on-set experiences, Fox enrolled her in the Actors’ Laboratory Theatre, an acting school where she was introduced to the techniques of the Group Theatre. Monroe herself later reflected on this experience, stating it was “my first taste of what real acting in a real drama could be, and I was hooked.” Despite her evident enthusiasm and growing commitment to her craft, her teachers at the time reportedly found her too shy and insecure to foresee a future in acting. Consequently, Fox did not renew her contract in August 1947, a setback that would have deterred many.

Undeterred, Monroe returned to modeling, supplementing her income with occasional odd jobs at film studios, such as working as a dancing “pacer” behind the scenes. Her resolve to become an actress remained unwavering; she continued her studies at the Actors’ Lab and sought opportunities to network. This included frequenting producers’ offices, befriending influential gossip columnist Sidney Skolsky, and entertaining male guests at studio functions. These efforts, coupled with the support of Fox executive Joseph M. Schenck, eventually led to a contract with Columbia Pictures in March 1948, marking a temporary move away from Fox and a continued pursuit of her acting ambitions.

At Columbia, her look underwent further refinement, modeled after Rita Hayworth, with her hair meticulously bleached platinum blonde. She began working with Natasha Lytess, the studio’s head drama coach, who would serve as her mentor until 1955. Her sole film at Columbia, the low-budget musical *Ladies of the Chorus* (1948), provided her first starring role as a chorus girl. Despite also screen-testing for a lead role in *Born Yesterday* (1950), her contract was not renewed in September 1948, and *Ladies of the Chorus*, released the following month, did not achieve success.

Read more about: The Great Escape: Why Angelina Jolie And Other A-Listers Are Rethinking Their American Lives

4. **The Breakthrough: Gaining Attention in Critical Roles**Following the expiration of her Columbia contract, Monroe once again found herself returning to the modeling circuit. This period saw her shoot a commercial for Pabst beer and, notably, pose for artistic nude photographs by Tom Kelley for John Baumgarth calendars, where she used the name ‘Mona Monroe.’ These photographic sessions, which included images previously taken where she posed topless or in a bikini, were a financial necessity and a practice she reportedly felt comfortable with. It was also around this time that she formed a significant relationship with Johnny Hyde, the vice president of the William Morris Agency, becoming both his protégée and mistress.

Through Hyde’s influential connections, Monroe secured small but impactful roles in several films, two of which were critically acclaimed and pivotal to her burgeoning career. The first was Joseph Mankiewicz’s drama *All About Eve* (1950), a film that garnered 14 Academy Award nominations. Although her screen time was limited, her performance caught the attention of none other than its star, Bette Davis, who later praised Monroe, stating, “Definitely, no question, I knew she was going to make it. She was a very ambitious girl, [and] knew what she wanted [and was] very serious about it…I thought she had talent.” This endorsement from a Hollywood veteran underscored Monroe’s undeniable presence.

The second significant role came in John Huston’s noir *The Asphalt Jungle* (1950). Despite appearing on screen for only a few minutes, her performance earned her a mention in *Photoplay* magazine, with biographer Donald Spoto noting that she “moved effectively from movie model to serious actress.” These roles, though brief, demonstrated her potential beyond merely a physical presence and began to shift critical perception towards her capabilities as an actress.

In December 1950, Johnny Hyde successfully negotiated a seven-year contract for Monroe with 20th Century-Fox, a crucial step in her career progression. This contract, however, included a provision allowing Fox to opt out of renewal each year. Tragically, Hyde died of a heart attack just days later, leaving Monroe devastated. Despite this personal loss, 1951 saw her in supporting roles across three moderately successful Fox comedies: *As Young as You Feel*, *Love Nest*, and *Let’s Make It Legal*. While these films primarily cast her as “essentially [as] a sexy ornament,” as Spoto described, she still managed to garner critical notice, with Bosley Crowther of *The New York Times* calling her “superb” in *As Young As You Feel* and Ezra Goodman of the *Los Angeles Daily News* naming her “one of the brightest up-and-coming [actresses]” for her work in *Love Nest*.

Her popularity with audiences continued to soar, evidenced by thousands of fan letters she received weekly. She was also recognized as “Miss Cheesecake of 1951” by the army newspaper *Stars and Stripes*, a testament to her widespread appeal among servicemen during the Korean War. By February 1952, the Hollywood Foreign Press Association further solidified her rising star status by naming her the “best young box office personality,” confirming that Marilyn Monroe was unequivocally on the path to major stardom.

Read more about: Barbara Feldon: Beyond Agent 99 – An In-Depth Look at the Enduring Legacy of ‘Get Smart’s’ Iconic Star

5. **The “Dumb Blonde” Persona: Rise to Sex Symbol Status**Monroe found herself at the epicenter of a significant scandal in March 1952 when she publicly disclosed that she had posed for nude calendar photographs in 1949. The studio, having learned of the photos and the public rumors surrounding them, collaborated with Monroe on a strategy: to admit to the images while emphasizing that she had been financially destitute at the time. This calculated move proved effective, garnering public sympathy and significantly escalating interest in her films. In the aftermath, Monroe graced the cover of *Life* magazine as the “Talk of Hollywood,” and gossip columnist Hedda Hopper famously declared her the “cheesecake queen” who had transformed into a “box office smash.” This surge in public curiosity prompted the rapid release of three of her films—*Clash by Night*, *Don’t Bother to Knock*, and *We’re Not Married!*—to capitalize on her heightened visibility.

Despite her burgeoning status as a sex symbol, Monroe expressed a clear desire to demonstrate a broader acting range. She had proactively enrolled in acting classes with Michael Chekhov and mime Lotte Goslar shortly after signing her Fox contract. *Clash by Night* and *Don’t Bother to Knock* offered her opportunities to portray more complex characters. In *Clash by Night*, a drama directed by Fritz Lang and co-starring Barbara Stanwyck, she immersed herself in the role of a fish cannery worker, even spending time in a Monterey cannery for preparation. Her performance earned positive reviews, with *The Hollywood Reporter* stating she “deserves starring status with her excellent interpretation” and *Variety* noting her “ease of delivery which makes her a cinch for popularity.” *Don’t Bother to Knock*, a thriller, saw her in a heavier dramatic role as a mentally disturbed babysitter, intended by Zanuck to test her capabilities. While reviews were mixed, with some critics deeming her inexperienced for the part and others blaming the script, these roles showcased her earnest efforts to move beyond mere physical appeal.

Nevertheless, her three other films released in 1952 largely reinforced her typecasting in comedic roles that emphasized her sex appeal. In *We’re Not Married!*, her part as a beauty pageant contestant was explicitly designed to “present Marilyn in two bathing suits,” as stated by its writer Nunnally Johnson. In Howard Hawks’s *Monkey Business*, opposite Cary Grant, she played a “dumb, childish blonde, innocently unaware of the havoc her sexiness causes around her.” She also appeared briefly in *O. Henry’s Full House* as a nineteenth-century street walker. These roles, combined with strategic publicity stunts, such as wearing a revealing dress as Grand Marshal at the Miss America Pageant parade and her notorious comment to Earl Wilson that she usually wore no underwear, further solidified her reputation as the preeminent “it girl” and new sex symbol of 1952.

By 1953, Monroe starred in three films that profoundly cemented her status as a major sex symbol and one of Hollywood’s most bankable performers. *Niagara*, a Technicolor film noir released in January, overtly leveraged her sex appeal, casting her as a femme fatale plotting her husband’s murder. The film’s marketing famously utilized a 30-second long shot of Monroe walking with a distinctive hip sway, and scenes showing her body covered only by a sheet or towel were considered shocking for the era. Despite protests from women’s clubs, *Niagara* proved immensely popular. *The New York Times* famously commented, “the falls and Miss Monroe are something to see,” acknowledging her seductive power even if she was not yet “the perfect actress.” This film, alongside her appearance in a pleated “sunburst” gold lamé dress at the Photoplay Awards, which became a sensation despite being barely seen in *Gentlemen Prefer Blondes*, firmly established her “look” and cemented her iconic visual appeal, prompting veteran star Joan Crawford to publicly criticize the behavior as “unbecoming an actress and a lady.”

6. **Confronting the Studio System: The Fight for Control**Despite her meteoric rise to becoming one of 20th Century-Fox’s most significant stars by 1953, Marilyn Monroe’s contract remained unchanged since 1950, placing her at a substantial disadvantage. She was paid significantly less than other stars of comparable stature and, critically, lacked the power to choose her own film projects. Her attempts to diversify her roles and appear in films that did not exclusively focus on her as a pin-up were routinely thwarted by studio head executive Darryl F. Zanuck. Zanuck, who reportedly held a strong personal dislike for Monroe, did not believe she would generate as much revenue for the studio in more serious or varied roles.

Under pressure from Spyros Skouras, the studio’s owner, Zanuck had also made a strategic decision for Fox to exclusively concentrate on entertainment-focused productions to maximize profits, leading to the cancellation of any “serious films.” This corporate directive further constrained Monroe’s artistic ambitions. The tensions reached a breaking point in January 1954 when Zanuck suspended Monroe after she refused to commence shooting another musical comedy, *The Girl in Pink Tights*. This act of defiance, which made front-page news, underscored her growing frustration with the restrictive nature of her contract and the studio’s refusal to acknowledge her evolving artistic aspirations.

Monroe’s refusal to be confined to a specific typecast, combined with her desire for greater control over her career and compensation commensurate with her star power, set the stage for a prolonged and very public battle with 20th Century-Fox. This conflict was not merely about money; it was about agency and artistic integrity within a studio system renowned for its control over its talent. Her willingness to challenge the established hierarchy, even at the risk of suspension and negative publicity, highlighted a profound determination to shape her professional destiny rather than simply be a pliable commodity.

This period also saw the release of *River of No Return* in April 1954, a western that Monroe herself candidly dismissed as a “Z-grade cowboy movie in which the acting finished second to the scenery and the CinemaScope process.” Despite her personal disdain, the film proved popular with audiences, further illustrating her undeniable box office appeal regardless of the project. Following her suspension, she was required by the studio to star in the musical *There’s No Business Like Show Business* as a condition for dropping *The Girl in Pink Tights*. Monroe strongly disliked this film, and upon its release in late 1954, it was largely unsuccessful, with many critics finding her performance vulgar, suggesting a mismatch between her evolving aspirations and the roles the studio continued to impose upon her.

7. **Marriage to Joe DiMaggio: A High-Profile Union and Its Demise**In the midst of her growing professional conflicts with 20th Century-Fox, Marilyn Monroe leveraged her private life to counter negative publicity and assert some personal agency. She and retired New York Yankees baseball star Joe DiMaggio, who had been dating for two years and represented one of the era’s most famous sports personalities, were married at the San Francisco City Hall on January 14, 1954. This high-profile union immediately became front-page news, capturing immense public attention and serving as a strategic move to soften her image following her studio suspension.

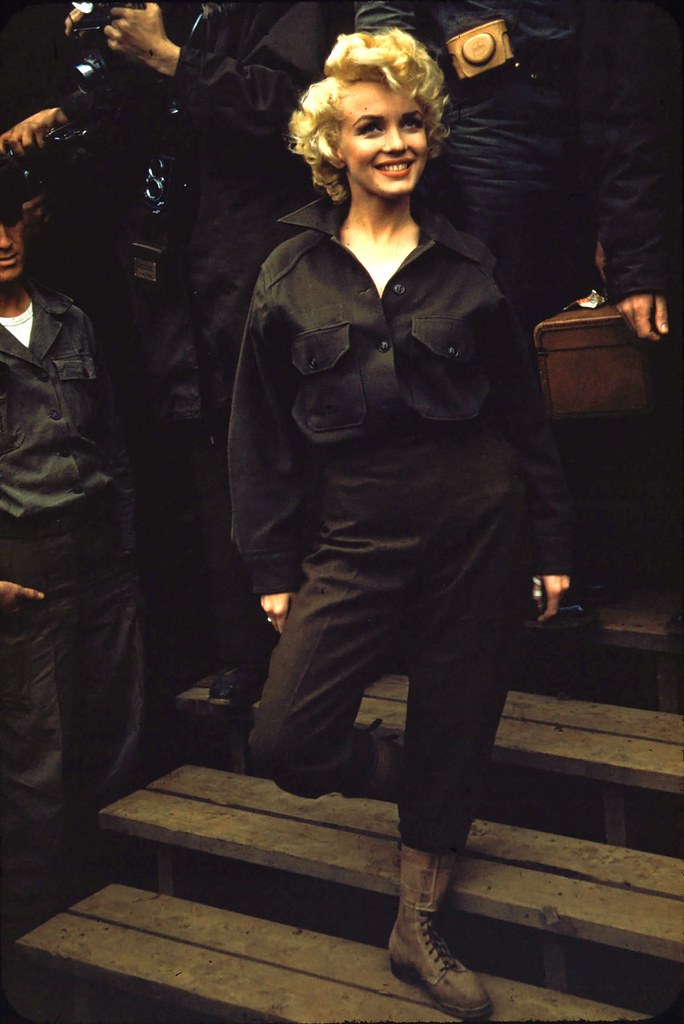

Just fifteen days after their wedding, the couple flew to Japan, ostensibly combining a “honeymoon” with DiMaggio’s business trip. From Tokyo, Monroe then traveled to Korea, where she participated in a USO show, performing for over 60,000 U.S. Marines over a four-day period. This gesture not only boosted troop morale but also further endeared her to the American public, presenting her as a patriotic figure. Upon her return to the United States, she was honored with Photoplay’s “Most Popular Female Star” prize, a clear indication that her public image, despite professional skirmishes, remained largely positive and immensely popular.

Monroe subsequently reached a settlement with Fox in March, which included the promise of a new contract, a significant bonus of $100,000, and a starring role in the film adaptation of the acclaimed Broadway success, *The Seven Year Itch*. This represented a significant victory in her ongoing battle for better terms and more substantive roles. However, her marriage to DiMaggio was simultaneously experiencing severe strain beneath the surface of public adoration and professional successes.

In September 1954, Monroe began filming Billy Wilder’s comedy *The Seven Year Itch*, starring opposite Tom Ewell. During production, a publicity stunt involving the filming of a scene on Lexington Avenue in Manhattan, where air from a subway grate blew up her white dress, drew nearly 2,000 spectators and placed Monroe on international front pages. This iconic moment, however, also marked the effective end of her marriage. The union had been plagued from its outset by DiMaggio’s intense jealousy and controlling behavior, which also manifested as physical abuse. After returning to Hollywood from New York City in October 1954, Monroe filed for divorce, ending their highly publicized marriage after only nine months, revealing the profound personal costs beneath the glamorous façade of her public life.

8. **Founding Marilyn Monroe Productions (MMP) and the Battle with Fox**Following the completion of *The Seven Year Itch* in November 1954, Marilyn Monroe made a decisive move, departing Hollywood for the East Coast to establish her own production company, Marilyn Monroe Productions (MMP), alongside photographer Milton Greene. This audacious step, later described as “instrumental” in accelerating the collapse of the traditional studio system, signaled Monroe’s profound dissatisfaction with her imposed roles and limited creative autonomy. She openly voiced her exhaustion with “the same old sex roles” and asserted that 20th Century-Fox had failed to uphold its contractual obligations, including a promised bonus, thereby nullifying her agreement.

This bold declaration ignited a year-long legal dispute with Fox, commencing in January 1955. The media landscape, often quick to uphold the established order, largely met Monroe’s actions with ridicule, portraying her as an overly ambitious actress stepping beyond her bounds. The sentiment was so pervasive that she found herself parodied in the Broadway play *Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?*, where a lookalike, Jayne Mansfield, depicted a ‘dumb actress’ daring to start her own production company.

Yet, beneath the public mockery, Monroe’s challenge represented a pivotal moment for artists seeking control over their careers within a rigid studio hierarchy. Her willingness to risk her burgeoning star status for artistic integrity resonated with a deeper, systemic discontent. This period of open defiance underscored not only her personal ambition but also her prescience in anticipating a shift in power dynamics, advocating for an artist’s right to self-determination in an industry that had long treated its stars as mere commodities.

9. **Embracing Method Acting and Lee Strasberg**Having founded MMP, Monroe relocated to Manhattan, dedicating the entirety of 1955 to the profound pursuit of her acting craft. This period marked a crucial shift from simply performing to deeply understanding the psychological underpinnings of her roles. She immersed herself in classes with Constance Collier and, most significantly, attended intensive workshops on method acting at the prestigious Actors Studio, then under the transformative guidance of Lee Strasberg.

Having founded MMP, Monroe relocated to Manhattan, dedicating the entirety of 1955 to the profound pursuit of her acting craft. This period marked a crucial shift from simply performing to deeply understanding the psychological underpinnings of her roles. She immersed herself in classes with Constance Collier and, most significantly, attended intensive workshops on method acting at the prestigious Actors Studio, then under the transformative guidance of Lee Strasberg.

Monroe quickly developed a close bond with both Lee Strasberg and his wife, Paula, finding in them not just mentors but a surrogate family. Her inherent shyness, a recurring theme throughout her early life, led to her receiving private lessons at their home, a testament to the Strasbergs’ personalized approach and their recognition of her unique needs. This intimate mentorship led her to replace her long-time acting coach, Natasha Lytess, with Paula Strasberg, solidifying the Strasbergs’ profound and enduring influence on her artistic development for the remainder of her career.

Lee Strasberg’s philosophy, which held that an actor must confront and channel their emotional traumas into their performances, deeply resonated with Monroe. It was during this time that she also began psychoanalysis, a therapeutic journey integral to Strasberg’s method. This intense period of introspection and rigorous training equipped her with tools to explore the complexities of character, moving far beyond the superficial interpretations that had defined her earlier ‘dumb blonde’ persona. Her commitment to method acting demonstrated a serious, unwavering dedication to being perceived as a legitimate dramatic actress.

Read more about: Christoph Waltz: Tracing the Path of an Austrian Actor’s Rise to International Acclaim and Cinematic Distinction

10. **The Hard-Won New Fox Contract: A Victory for Artistic Freedom**Amidst her ongoing legal battle with Fox and her dedicated studies, Marilyn Monroe’s personal life continued to be a subject of intense public and private scrutiny. Her relationship with retired baseball star Joe DiMaggio, though their divorce proceedings were still underway, continued intermittently, as did a brief, on-again, off-again affair with actor Marlon Brando, which he later claimed lasted until her death. However, it was her burgeoning and increasingly serious affair with playwright Arthur Miller that captured significant attention, particularly after her divorce was finalized in October 1955, coinciding with Miller’s separation from his wife, Mary Slattery.

This relationship, however, was met with strong disapproval from the studio, which urged Monroe to terminate it. Miller was then under investigation by the FBI for alleged communist sympathies and had been subpoenaed by the House Un-American Activities Committee. Monroe, undeterred by the professional and political pressures, steadfastly refused to end the relationship, a decision that led to the FBI initiating a file on her. Despite extensive investigation, the FBI ultimately found no evidence directly linking her to the Communist Party, concluding only that her “views are very positively and concisely leftist” but that her active involvement with the movement was not widely known among its Los Angeles members.

By the close of 1955, a pivotal resolution was reached. Recognizing that MMP could not independently finance film productions and eager to regain their most marketable star, 20th Century-Fox and Monroe signed a new, landmark seven-year contract. This agreement was a monumental victory for Monroe, granting her $400,000 for four films and, crucially, the unprecedented right to choose her own projects, directors, and cinematographers. The contract also stipulated that she could produce one film with MMP for every film she completed for Fox, marking a significant shift in power dynamics within the industry.

Further asserting her autonomy and shedding the remnants of her past, Monroe legally changed her name to Marilyn Monroe on February 23, 1956. The press, which had once mocked her, now lauded her as a “shrewd businesswoman” and predicted her triumph would serve as “an example of the individual against the herd for years to come.” Despite these accolades, her relationship with Miller still drew negative commentary, with some pundits like Walter Winchell labeling her “America’s best-known blonde moving picture star is now the darling of the left-wing intelligentsia,” underscoring the era’s complex blend of cultural fascination and political unease surrounding her choices.

11. **Critically Acclaimed Dramatic Performances: *Bus Stop***With her newfound contractual freedom, Marilyn Monroe immediately embarked on a project that would definitively showcase her capabilities as a serious actress: the drama *Bus Stop*. Filming commenced in March 1956, marking her inaugural cinematic endeavor under the terms of her hard-won new agreement. In this role, Monroe portrayed Chérie, a captivating yet vulnerable saloon singer whose aspirations for stardom are complicated by the persistent affections of a naive cowboy.

Monroe’s dedication to the role was exemplary, demonstrating a profound commitment to authenticity. She diligently learned an Ozark accent, a meticulous detail that added depth to her character. Furthermore, she consciously selected costumes and makeup that eschewed the overt glamour of her previous films, embracing a more understated and realistic aesthetic. Even her singing and dancing were deliberately modulated to be mediocre, fitting the character’s provincial background rather than her established showgirl persona.

Broadway director Joshua Logan, initially skeptical of Monroe’s acting abilities and well aware of her reputation for being difficult, agreed to direct the film. The production, shot across Idaho and Arizona, saw Monroe, as the head of MMP, exert “technical charge,” occasionally influencing decisions on cinematography. Logan, witnessing her perfectionism and chronic lateness firsthand, adapted his directorial style. This challenging yet ultimately rewarding collaboration transformed Logan’s opinion, leading him to later draw comparisons between Monroe and Charlie Chaplin, acknowledging her remarkable ability to seamlessly blend comedy and tragedy.

Upon its release in August 1956, *Bus Stop* was met with widespread critical and commercial acclaim. Publications like *The Saturday Review of Literature* lauded her performance, declaring it “effectively dispels once and for all the notion that she is merely a glamour personality.” Bosley Crowther of *The New York Times*, a seasoned and often discerning critic, unequivocally proclaimed, “Hold on to your chairs, everybody, and get set for a rattling surprise. Marilyn Monroe has finally proved herself an actress.” This resounding critical endorsement culminated in a well-deserved Golden Globe nomination for Best Actress in a Leading Role – Musical or Comedy, firmly establishing her as a versatile and formidable talent.

12. **Marriage to Arthur Miller and Challenges of *The Prince and the Showgirl***In the midst of her professional triumphs, Marilyn Monroe’s personal life took another significant turn with her marriage to Arthur Miller. On June 29, 1956, they were wed in a brief civil ceremony at the Westchester County Court in White Plains, New York, followed two days later by a Jewish ceremony at the home of Miller’s literary agent, Kay Brown, in Waccabuc, New York. Monroe’s decision to convert to Judaism upon her marriage had geopolitical repercussions, leading to Egypt’s immediate ban on all of her films within its borders. The media, fascinated by the perceived intellectual disparity between the iconic sex symbol and the celebrated playwright, sensationally framed the union as a mismatch, exemplified by *Variety*’s memorable headline: “Egghead Weds Hourglass.”

Despite the external scrutiny and her recent critical success with *Bus Stop*, Monroe’s next venture, MMP’s first independent production, *The Prince and the Showgirl*, proved to be a challenging experience. Filming began in August 1956 at Pinewood Studios in England, with the added complexity of Laurence Olivier serving as director, co-producer, and co-star. From the outset, the production was plagued by significant conflicts between Olivier and Monroe. Olivier’s patronizing demeanor, including his dismissive instruction “All you have to do is be sexy,” and his insistence that Monroe replicate Vivien Leigh’s stage interpretation of the character, deeply angered her.

Olivier’s clear disdain for the constant presence of Paula Strasberg, Monroe’s acting coach, further exacerbated tensions. In what became a deliberate act of retaliation, Monroe responded by becoming uncooperative and frequently arriving late to the set, later articulating her rationale: “if you don’t respect your artists, they can’t work well.” Beyond these interpersonal clashes, Monroe faced other personal struggles during this period. Her dependence on pharmaceuticals escalated, and according to biographer Donald Spoto, she experienced a miscarriage, adding to the immense pressures she was under. Furthermore, irreconcilable disagreements regarding the management of MMP emerged between her and Milton Greene.

Despite the numerous difficulties and the tumultuous atmosphere, filming for *The Prince and the Showgirl* was completed on schedule by the end of 1956. However, upon its release in June 1957, the film received mixed reviews and struggled to find an audience in America. Paradoxically, it was better received in Europe, where Monroe’s performance earned her prestigious accolades such as the Italian David di Donatello and the French Crystal Star awards, along with a nomination for a BAFTA, underscoring the divergent critical perceptions of her work across continents.

Read more about: Beyond the Spotlight: Unveiling the Unseen Truths and Troubled Soul of Marilyn Monroe’s Private Life

13. **Continued Struggles and Triumph with *Some Like It Hot***Following her return from England, Marilyn Monroe took an eighteen-month hiatus from filmmaking, seeking to prioritize her family life with Arthur Miller. During this period, they divided their time between New York City, Connecticut, and Long Island. However, this private interlude was not without its own profound difficulties, as Monroe endured an ectopic pregnancy in mid-1957, followed by a miscarriage a year later, reproductive challenges most likely linked to her documented endometriosis. Adding to her personal struggles, she was also briefly hospitalized due to a barbiturate overdose, a stark reminder of the anxieties that continued to plague her. Concurrently, her inability to reconcile disagreements with Milton Greene over the direction of MMP ultimately led her to buy out his share of the company.

In July 1958, Monroe made her highly anticipated return to Hollywood, starring opposite Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis in Billy Wilder’s groundbreaking comedy on gender roles, *Some Like It Hot*. Despite her initial reservations, considering the role of Sugar Kane yet another iteration of the “dumb blonde” archetype, she accepted it, encouraged by Miller and enticed by an offer of 10% of the film’s profits on top of her standard pay. The production of *Some Like It Hot* rapidly became “legendary” for its profound difficulties, largely centered around Monroe’s on-set behavior.

Her struggles were well-documented: she demanded dozens of retakes, frequently forgot her lines, and often diverged from directorial instructions. Tony Curtis famously quipped that kissing her was “like kissing Hitler” due to the sheer number of takes required. Monroe herself privately likened the production to a “sinking ship” and, in a moment of candid frustration, commented on her co-stars and director, saying, “[but] why should I worry, I have no phallic symbol to lose.” Many of the film’s problems stemmed from her disagreements with Wilder, who himself possessed a reputation for being challenging. Monroe angered him by requesting alterations to many of her scenes, a dynamic that paradoxically worsened her stage fright, and it is suggested that she even deliberately sabotaged several scenes to execute them according to her own artistic vision.

Despite the tumultuous production, Wilder ultimately expressed immense satisfaction with Monroe’s performance, famously stating, “Anyone can remember lines, but it takes a real artist to come on the set and not know her lines and yet give the performance she did!” *Some Like It Hot* was released in March 1959 to widespread critical and commercial acclaim, becoming a monumental success. Monroe’s nuanced and memorable portrayal of Sugar Kane earned her a Golden Globe for Best Actress, solidifying her triumph over the film’s considerable on-set challenges and proving her undeniable comedic prowess.

Read more about: Beyond the Bombshell: Unearthing 14 Hidden Truths About Marilyn Monroe’s Life, Loves, and Legacy

14. **Lasting Legacy: A Pop Culture Icon**Following the success of *Some Like It Hot*, Marilyn Monroe continued her cinematic journey, culminating in her last completed film, the powerful drama *The Misfits*, released in 1961. This role, penned by her then-husband Arthur Miller and co-starring screen legends Clark Gable and Montgomery Clift, offered a glimpse into a more raw and vulnerable side of her acting, further cementing her range beyond the comedic and overtly glamorous. It was a poignant final curtain call for an actress who had battled so fiercely for artistic recognition.

However, Monroe’s life was tragically cut short. On August 4, 1962, at the tender age of 36, she was discovered deceased at her Los Angeles home, the victim of an overdose of barbiturates. Her death, swiftly ruled a probable suicide, sent shockwaves across the globe, leaving behind a legacy unfinished and a profound sense of loss for millions of fans and admirers. The abruptness of her passing only intensified the mystique that had surrounded her throughout her career, forever embedding her image in the collective consciousness.

Decades later, Marilyn Monroe remains an unparalleled pop culture icon, her image, style, and persona enduring as powerful symbols that transcend generations. Her influence is not merely confined to cinema; she continues to inspire fashion, art, and ongoing discourse about fame, identity, and the pressures faced by women in the public eye. The American Film Institute, in recognition of her monumental impact and enduring star power, has ranked her as the sixth-greatest female screen legend from the Golden Age of Hollywood, a testament to her indelible mark on both the industry and popular imagination.

Read more about: 14 Totally Underrated ’80s Actors Who Deserved Way More Shine!

Her journey from a troubled childhood to a global phenomenon, marked by personal struggles and professional triumphs, continues to captivate. Marilyn Monroe was more than just a ‘blonde bombshell’; she was a complex, ambitious, and deeply sensitive woman who challenged the conventions of her time, leaving an imprint on culture that few have matched. Her story serves as a timeless narrative of the intoxicating allure and profound costs of superstardom, a legacy that continues to resonate with undeniable force.