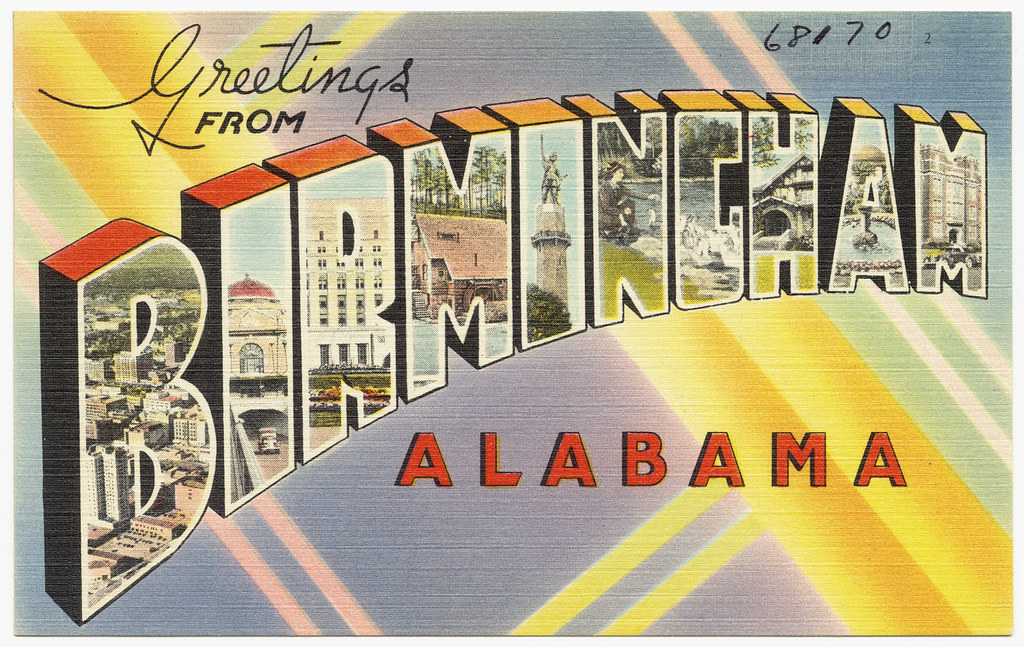

Alabama, often distilled into convenient Southern tropes, is a state far more intricate and dynamic than its popular image suggests. Beyond the football fields and the ‘Heart of Dixie’ moniker lies a rich, often tumultuous, history intertwined with a strikingly diverse landscape. It’s a place where ancient civilizations left their indelible marks, European powers clashed for centuries, and a vibrant, yet challenging, narrative unfolded to shape its present.

To truly grasp Alabama, one must move beyond the surface and delve into the layers of its past and present. This isn’t merely a recounting of facts; it’s an analytical exploration, a critical look at how geography, etymology, and pivotal historical moments have forged the unique identity of this Deep South state. We’ll unpack the complexities, from its earliest inhabitants to the foundational economic structures that defined its early development.

In this initial deep dive, we embark on a journey through Alabama’s origins. We’ll trace the fascinating linguistic roots of its name, explore the diverse geographical tapestry that defines its regions, and uncover the sophisticated indigenous cultures that thrived long before European contact. We’ll then navigate the intricate colonial chess game, witness the birth of Alabama as a state, and examine the profound impact of cotton and slavery on its antebellum society, laying the groundwork for many of the challenges and triumphs that would follow.

1. **The Name: A Linguistic Journey**The very name ‘Alabama’ carries with it a deep historical resonance, derived directly from the Alabama people, a Muskogean-speaking tribe. These early inhabitants lived just below the confluence of the Coosa and Tallapoosa rivers, an area that became central to the state’s formation. The word for a person of Alabama lineage, ‘Albaamo,’ or variations like ‘Albaama’ or ‘Albàamo,’ serves as a direct link to the state’s indigenous heritage.

Intriguingly, the spelling of the name has fluctuated significantly throughout historical records. Early accounts from the Hernando de Soto expedition in 1540 offer a glimpse into these variations: Garcilaso de la Vega recorded ‘Alibamo,’ while the Knight of Elvas and Rodrigo Ranjel noted ‘Alibamu’ and ‘Limamu,’ respectively. Later, by 1702, the French had adopted ‘Alibamon,’ even labeling the river ‘Rivière des Alibamons’ on their maps, demonstrating how European transcription shaped its early recognition.

While the origin is clearly indigenous, the precise meaning of ‘Alabama’ remains a subject of scholarly debate. Some suggest a Choctaw derivation from ‘alba’ (meaning ‘plants’ or ‘weeds’) and ‘amo’ (meaning ‘to cut,’ ‘to trim,’ or ‘to gather’), leading to interpretations like ‘clearers of the thicket’ or ‘herb gatherers.’ This could refer to agricultural land clearing or the collection of medicinal plants. However, a popular, yet unsubstantiated, 1842 article in the Jacksonville Republican proposed the romanticized meaning ‘Here We Rest,’ a notion that, despite its poetic appeal, has been unsupported by experts in Muskogean languages.

Read more about: Stephen: 14 Mind-Blowing Revelations About a Name That Shaped History

2. **A Land of Contrasts: Alabama’s Diverse Geography**Alabama’s physical landscape is a study in remarkable diversity, spanning from the mountainous terrains of its north to the serene coastal plains of its south. As the 30th largest state in the U.S. by area, encompassing 52,419 square miles, it boasts an impressive 3.2% water area, ranking it 23rd nationally for surface water and securing its place as having the second-largest inland waterway system in the country. This abundance of water resources has historically shaped its settlement patterns and economic development.

A significant portion of Alabama, roughly three-fifths of its land area, belongs to the Gulf Coastal Plain. This gentle expanse gradually descends towards the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico, characterizing much of the state’s southern and central regions. This fertile plain, with its moderate elevation, contrasts sharply with the state’s northern reaches. There, the terrain becomes predominantly mountainous, dominated by the majestic Tennessee Valley, which carves out an intricate network of creeks, streams, rivers, mountains, and lakes, defining a distinct ecological and topographical identity.

The state’s elevation variations further underscore its geographical dynamism, ranging from sea level at Mobile Bay to over 2,000 feet in the northeast, culminating at Mount Cheaha, which stands proudly at 2,413 feet. Forests are a dominant feature, covering 22 million acres, or 67% of Alabama’s total land area, contributing significantly to its biodiversity. Notably, Baldwin County, situated along the Gulf Coast, holds the distinction of being the largest county in the state in terms of both land and water area, a testament to the scale of its coastal and estuarine environments.

3. **Ancient Roots: Pre-European Alabama**Long before European explorers set foot on its shores, the land that would become Alabama was a vibrant mosaic of indigenous cultures, inhabited by diverse peoples for thousands of years. These early societies were sophisticated, developing complex social structures and extensive trade networks. Evidence suggests that trade with northeastern tribes along the Ohio River was well-established during the Burial Mound Period, which spanned from 1000 BC to 700 AD, a testament to the interconnectedness of ancient North American peoples.

A major cultural force that shaped much of the state from 1000 to 1600 AD was the agrarian Mississippian culture. This civilization, renowned for its large-scale mound building and complex societies, established one of its most significant centers at what is now the Moundville Archaeological Site in Moundville, Alabama. This site represents the second-largest complex of the classic Middle Mississippian era, surpassed only by Cahokia in Illinois, highlighting its immense regional importance as a hub of political, ceremonial, and social life.

Artifacts unearthed from Moundville have been instrumental in helping scholars understand the characteristics of the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (SECC), a major component of the Mississippian peoples’ religion and cosmology. Contrary to earlier theories, the SECC appears to have developed independently, without direct links to Mesoamerican cultures, showcasing the unique cultural innovations of these indigenous groups. At the time of European contact, historical Native American tribes in present-day Alabama included the Iroquoian-speaking Cherokee and the Muskogean-speaking Alabama (Alibamu), Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Koasati, each contributing to the rich tapestry of the region’s pre-colonial heritage.

4. **Colonial Crossroads: European Powers Vie for Control**Alabama’s colonial history is a complex narrative of competing European ambitions, with Spain, France, and Great Britain each leaving their indelible mark. The Spanish were the first Europeans to explore the region, with Hernando de Soto’s expedition passing through Mabila and other parts of the state in 1540. However, it was the French who established the region’s first enduring European settlement, founding Old Mobile in 1702, which later moved to its current site in 1711. This area was claimed by the French as part of La Louisiane from 1702 to 1763, establishing a significant early presence.

The geopolitical landscape shifted dramatically after the French defeat to the British in the Seven Years’ War. From 1763 to 1783, the territory became part of British West Florida. The American Revolutionary War then brought further reconfigurations, dividing the territory between the fledgling United States and Spain. Spain, tenacious in its hold, retained control of this western territory, including Mobile, until the Spanish garrison finally surrendered to U.S. forces on April 13, 1813, marking a definitive end to direct European colonial rule.

Early white settlement outside Mobile began in the 1770s, with figures like Thomas Bassett, a British loyalist, settling in the Tombigbee District. This district, primarily encompassing areas around the Tombigbee River, laid the groundwork for future county divisions. The fluidity of claims continued: what are now Baldwin and Mobile counties cycled through Spanish West Florida, the independent Republic of West Florida, and finally into the Mississippi Territory by 1812. Furthermore, much of what is now the northern two-thirds of Alabama, known as the Yazoo lands, was claimed by the Province of Georgia from 1767, a claim heavily disputed even after the American Revolutionary War, adding layers of jurisdictional complexity to the nascent American South.

5. **Becoming a State: The 19th Century Frontier**The genesis of Alabama’s statehood in the 19th century was directly linked to the burgeoning pressures for expansion and the establishment of new slave states in the American South. Debates over the division of the vast Mississippi Territory quickly arose, driven by white southerners eager to solidify their political and economic interests. In response to these demands, Congress formally created the Alabama Territory on March 3, 1817, appointing William Wyatt Bibb of Georgia as its inaugural governor, setting the stage for its eventual admission into the Union.

This legislative act effectively carved out the eastern, more sparsely settled half of the Mississippi Territory, marking its distinct administrative identity. St. Stephens, a settlement now largely abandoned, played a crucial, albeit temporary, role as the territorial capital from 1817 to 1819. This period of territorial governance was short-lived, signaling the rapid pace of development and the urgent desire for self-determination among its growing population.

Alabama’s full recognition as the 22nd state came swiftly on December 14, 1819. In a significant move, Congress selected Huntsville as the location for the first Constitutional Convention, where delegates convened from July 5 to August 2, 1819, to draft the foundational document for the new state. Huntsville served as the temporary capital until 1820, when the seat of government moved to Cahaba in Dallas County, a town that would itself become a ghost town, illustrating the transient nature of early state capitals. From 1826 to 1846, Tuscaloosa held the capital, before Montgomery ultimately became the permanent seat of government in 1847, with its iconic capitol building erected and rebuilt following a fire, standing to this day.

The period surrounding Alabama’s admission was characterized by the ‘Alabama Fever’ land rush, a frenetic influx of settlers and speculators. They poured into the state, drawn by the promise of fertile land ideally suited for cotton cultivation. This frontier environment, particularly in the 1820s and 1830s, saw a rapid population explosion, from under 10,000 in 1810 to over 300,000 by 1830. Its early constitution, reflecting the democratic ideals of the era for its dominant demographic, notably provided for universal suffrage for white men, a stark contrast to the unfolding tragedy of Native American removal from the state within a few years of the 1830 Indian Removal Act.

Read more about: America’s Unfolding Story: Some Defining Moments That Forged a Global Power and Shaped a Nation

6. **The Antebellum Economy: Cotton, Slavery, and the Black Belt**The antebellum period in Alabama was profoundly defined by the explosive growth of its cotton economy, a force that reshaped its landscape, demography, and social structure. Southeastern planters and traders, migrating from the Upper South, brought with them not only their agricultural expertise but, crucially, their enslaved labor force. As cotton plantations expanded across the fertile lands, particularly within the central Black Belt region, the wealth of these owners became inextricably linked to the systematic exploitation of African American slave labor.

The Black Belt, named for its dark, productive soil, quickly became the economic engine of Alabama. Its rich soil was ideal for cotton, turning vast tracts of land into immensely profitable agricultural enterprises. This economic model, however, was predicated on a deeply entrenched system of human bondage, transforming Alabama into one of the nation’s leading cotton producers. Beyond the wealthy planters, the region also attracted a significant number of poor, disenfranchised individuals who sought to carve out a living as subsistence farmers, creating a complex social hierarchy that stratified based on land ownership and race.

The sheer scale of this economic transformation and its reliance on enslaved labor is starkly illustrated by Alabama’s demographic shifts. From a population of fewer than 10,000 in 1810, the state burgeoned to over 300,000 by 1830, a testament to the aggressive expansion of the cotton frontier. This rapid growth was directly fueled by the coerced migration of enslaved people, whose unpaid labor was the bedrock of this agricultural prosperity. The forced removal of most Native American tribes following the Indian Removal Act of 1830 further opened up lands for these expanding plantations, intensifying the demand for labor.

By 1860, on the eve of the Civil War, Alabama’s population had swelled to 964,201 people. A staggering proportion of this population, nearly half, were enslaved African Americans, totaling 435,080 individuals, alongside a small number of 2,690 free people of color. This demographic reality underscores the absolute centrality of slavery to Alabama’s economic identity and its social fabric. The state’s prosperity, indeed its very way of life, was fundamentally interwoven with cotton production and the institution of slavery, making the ensuing conflict over these issues an existential one for Alabama.

Having laid the groundwork of Alabama’s origins and antebellum life, we now turn to the profound upheavals and transformative struggles that defined its path through the 19th and 20th centuries, and continue to shape its identity today. From the fires of secession to the quiet dignity of civil rights protests, Alabama has been a crucible of American experience, grappling with internal divisions, economic reinvention, and the relentless forces of nature. This next chapter delves into the complexities of its Civil War legacy, the entrenched systems of Jim Crow, dramatic industrial shifts, its pivotal role in national movements, and the unique natural tapestry that both sustains and challenges its people.

.jpg)

7. **The Crucible of Conflict: Civil War and Reconstruction**By 1860, Alabama was a demographic anomaly, with a staggering 435,080 enslaved African Americans making up nearly half of its total population of 964,201. The state’s entire economic and social framework was so deeply interwoven with the institution of slavery and cotton production that the escalating national tensions became an existential threat. This profound reliance on human bondage propelled Alabama’s swift declaration of secession from the Union on January 11, 1861, briefly existing as an independent republic before joining the Confederate States of America, with Montgomery controversially serving as its initial capital.

Though relatively few major battles scarred Alabama’s soil directly, the state was far from a quiet participant. It contributed approximately 120,000 soldiers to the Confederate war effort, a significant commitment that saw its young men fighting on distant battlefields. The iconic “Yellowhammer” nickname, originally attributed to a company of cavalry from Huntsville, clad in new uniforms with yellow trim, quickly extended to all Alabama troops in the Confederate Army, a lasting symbol of their involvement.

Following the Confederacy’s collapse, Alabama found itself under military rule from May 1865 until its official restoration to the Union in 1868. This period of Reconstruction brought about radical shifts, as the 13th Amendment in 1865 legally freed Alabama’s enslaved population. With most white citizens temporarily barred from voting, and freedmen newly enfranchised, African Americans rose to prominence as political leaders, with figures like Jeremiah Haralson, Benjamin S. Turner, and James T. Rapier representing Alabama in Congress, a truly groundbreaking, albeit fleeting, development.

Amidst these political transformations, the Reconstruction era constitution, ratified in 1868, introduced Alabama’s first public school system and even expanded women’s rights, signaling a progressive, if fragile, new direction. However, these advancements were fiercely contested. Reconstruction’s brief dawn was violently eclipsed as organized insurgent groups, including the notorious Ku Klux Klan, the Pale Faces, Knights of the White Camellia, Red Shirts, and the White League, emerged to suppress freedmen and Republicans through systematic intimidation and terror. This orchestrated backlash ultimately led to the Democrats regaining control of the legislature and governor’s office in 1874 through an election marred by fraud and violence, effectively ending Reconstruction and setting the stage for a new era of oppression.

Read more about: Tran Trong Duyet: Unpacking the Complex Legacy of John McCain’s Captor at the ‘Hanoi Hilton’ and His Journey Towards Reconciliation

8. **The Shadow of Jim Crow and 20th-Century Disenfranchisement**With the Democrats firmly back in power after 1874, Alabama quickly moved to solidify white supremacy and rollback the gains of Reconstruction. A new constitution in 1875 was followed by legislative acts that enshrined racial segregation into law, beginning with racially segregated schools and extending to railroad passenger cars by 1891. This was merely the overt precursor to the far more insidious system that would define the state for decades.

Perhaps the most impactful tool of this new order was the 1901 constitution, a document ingeniously crafted to disenfranchise vast segments of the population. It imposed stringent voter registration provisions, including a poll tax and a literacy test, which were selectively applied to effectively bar nearly all African Americans and Native Americans from voting, alongside tens of thousands of poor European Americans. The impact was immediate and devastating: by 1903, a mere 2,980 African Americans were registered in Alabama, a stark drop from the over 181,000 eligible just three years prior, despite widespread literacy among Black citizens. This systematic exclusion of Black voters would persist until the mid-20th century, rendering them politically voiceless.

Beyond voting rights, racial segregation permeated every aspect of public life, with additional laws passed into the 1950s that mandated segregated jails (1911), hospitals (1915), toilets, hotels, and restaurants (1928), and even bus stop waiting rooms (1945). The rural-dominated state legislature, consistently underfunded schools and services for African Americans, creating a dual system of profoundly unequal resources. In a poignant testament to community resilience, the Rosenwald Fund stepped in, partially financing the construction of 387 schools, seven teachers’ houses, and vocational buildings for African American children across the state by 1937, with Black residents effectively taxing themselves twice over to raise matching funds and contribute land and labor.

However, the combination of chronic racial discrimination, rampant lynchings, and agricultural depression, exacerbated by boll weevil infestations that devastated cotton crops, triggered a seismic demographic shift: the Great Migration. Tens of thousands of African Americans, fleeing the oppressive conditions of rural Alabama, sought opportunity in the industrial cities of the North and Midwest during the early 20th century. This exodus was so profound that Alabama’s population growth rate nearly halved between 1910 and 1920, leaving an undeniable mark on its demographic landscape.

9. **Alabama’s Industrial Evolution and Legislative Stagnation**While rural Alabama experienced the out-migration of the Great Migration, its cities, particularly Birmingham, began a dramatic transformation. This burgeoning urban center, affectionately dubbed the “Magic City” for its rapid growth, attracted a significant influx of rural workers seeking industrial jobs. By 1920, Birmingham had ascended to become the 36th-largest city in the United States, its economy firmly rooted in heavy industry and mining. Yet, this economic dynamism was met with political stagnation, as urban interests, despite contributing over a third of the state’s tax revenue, remained consistently underrepresented in a legislature that stubbornly refused to reapportion seats based on population, clinging to outdated district boundaries to maintain rural political power.

The mid-20th century saw the Alabama legislature employ increasingly sophisticated tactics to further entrench disenfranchisement, particularly as courts began to recognize Black voting rights. Constitutional amendments were ratified to grant local registrars greater power to disqualify Black applicants. In an astonishing move of racial “gerrymandering,” the boundaries of Tuskegee were contorted into a 28-sided figure explicitly designed to exclude Black residents from the city limits, a move the Supreme Court unanimously struck down. Later, in 1961, the legislature diluted the impact of Black votes by instituting numbered place requirements for local elections, illustrating a desperate, multi-pronged effort to maintain political control.

World War II proved to be an unexpected catalyst for change, ushering in a level of prosperity the state hadn’t seen since before the Civil War. War-related industries attracted a massive influx of rural workers to Alabama’s largest cities, most notably Mobile, which saw over 89,000 new residents between 1940 and 1943. This economic diversification began to shift Alabama’s reliance away from cotton and other cash crops towards a burgeoning manufacturing and service base. Despite these shifts, the fundamental issue of legislative malapportionment persisted, with a 1960 study revealing that “a minority of about 25% of the total state population is in majority control of the Alabama legislature,” effectively silencing urban voices and perpetuating inequities. This systemic imbalance would only be challenged by landmark U.S. Supreme Court cases like *Baker v. Carr* (1962) and *Reynolds v. Sims* (1964), which mandated “one man, one vote” as the basis for legislative districts.

10. **The Epicenter of Change: Alabama and the Civil Rights Movement**Against the backdrop of entrenched Jim Crow laws and legislative foot-dragging, Alabama became a pivotal battleground for the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s. African Americans, often through legal challenges and non-violent direct action, tirelessly pressed to dismantle disenfranchisement and segregation. While the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 *Brown v. Board of Education* ruling called for public school desegregation, Alabama, under the defiant leadership of Governor George Wallace, famously resisted compliance, making the state a symbol of Southern resistance.

It was within Alabama’s borders that some of the most iconic and consequential events of the Civil Rights Movement unfolded. The Montgomery bus boycott (1955–1956), sparked by Rosa Parks’ courageous stand, demonstrated the power of collective action. The Freedom Rides in 1961 exposed the brutality of segregation to a national audience. Most profoundly, the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches, met with violent repression, galvanized national support, directly contributing to the passage and enactment of the monumental Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 by the U.S. Congress. These legislative victories fundamentally reshaped the legal landscape of the nation.

Even after legal segregation formally ended in 1964, many Jim Crow customs lingered, requiring further legal challenges to dismantle completely. By 2017, Alabama’s African American population was largely concentrated in cities like Birmingham and Montgomery, though the “Black Belt region across central Alabama” continued to be “home to largely poor counties that are predominantly African-American,” highlighting persistent economic and racial disparities. The impact of the movement, however, was undeniable. In 1972, for the first time since 1901, the legislature completed congressional redistricting based on population, finally benefiting urban areas and historically underrepresented populations.

Further legal action, such as the 1980s omnibus redistricting case *Dillard v. Crenshaw County*, challenged at-large voting systems that had diluted minority votes in 180 Alabama jurisdictions. Settlements from this case led to significant reforms: five Alabama cities and counties, including Chilton County, adopted cumulative voting, and 23 jurisdictions, like Conecuh County, implemented limited voting. These innovative forms of proportional representation successfully increased the election of African Americans and women to local offices, fostering governments that are far more representative of their diverse citizenry, a testament to the enduring legacy of the civil rights struggle.

11. **Navigating the 21st Century: Economic Shifts and Lingering Challenges**As Alabama entered the latter half of the 20th century, its economy began a critical shift away from traditional industries like lumber, steel, and textiles, which faced increasing foreign competition. Steel jobs, for instance, saw a dramatic decline from 46,314 in 1950 to just 14,185 by 2011. This decline necessitated a new economic direction, and Alabama found it, particularly in Huntsville, which became a hub of innovation with the opening of NASA’s George C. Marshall Space Flight Center in 1960. This facility, crucial to the Saturn rocket program and the space shuttle, significantly boosted the state’s economic growth by cultivating a vibrant local aerospace industry.

The turn of the millennium has seen Alabama’s economy continue to diversify, with technology and manufacturing industries, especially automotive assembly, replacing some of its older industrial mainstays. The state’s 21st-century economy is now robustly based on automotive, finance, tourism, manufacturing, aerospace, mineral extraction, healthcare, education, retail, and technology sectors, marking a significant departure from its agrarian past. Despite this impressive economic and industrial growth in recent decades, Alabama continues to grapple with persistent challenges, typically ranking low nationally in crucial indicators such as health outcomes, educational attainment, and median household income, suggesting that prosperity is not yet universally shared.

Beyond economic hurdles, Alabama has also faced moments of intense cultural and political contention in the 21st century. A notable flashpoint occurred in 2001 when Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice Roy Moore installed a statue of the Ten Commandments in the capitol in Montgomery. The ensuing legal battle, which saw the 11th U.S. Circuit Court order its removal, sparked considerable protests in favor of retaining the monument, highlighting the deep cultural and religious fault lines that continue to run through the state, even as it strives for modernity.

12. **Nature’s Majesty and Fury: Alabama’s Diverse Landscape and Climate**Alabama’s physical geography is a tapestry of striking contrasts, making it the 30th largest state by area with 52,419 square miles. A significant three-fifths of its land falls within the gentle expanse of the Gulf Coastal Plain, gradually descending towards the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico. Yet, the northern reaches present a mountainous terrain dominated by the Tennessee Valley, an intricate network of creeks, streams, rivers, and lakes, culminating in Mount Cheaha, the state’s highest point at 2,413 feet. This diverse landscape is further enriched by its vast forest cover, with 22 million acres accounting for 67% of the state’s total land area, contributing to its remarkable biodiversity, often ranking among the top states nationally.

The state is also home to an impressive array of natural wonders. Winston County boasts the “Natural Bridge” rock, the longest natural bridge east of the Rockies. Marshall County’s Cathedral Caverns, famed for its cathedral-like entrance and massive stalagmite, offers an underground spectacle. Fairhope’s Ecor Rouge provides the highest coastline point between Maine and Mexico, while Childersburg’s DeSoto Caverns holds the distinction of being the first officially recorded cave in the United States. Other highlights include Noccalula Falls, Dismals Canyon, Stephens Gap Cave, and the breathtaking Little River Canyon, showcasing a geological richness that enthralls both residents and visitors.

Alabama’s climate is predominantly humid subtropical (Cfa), characterized by very hot summers and mild winters, with an average annual temperature of 64 °F (18 °C). The state receives a copious average of 56 inches of rainfall annually, supporting a lengthy growing season of up to 300 days in the south. However, this verdant landscape also lies in the path of nature’s fury. Alabama is highly susceptible to tropical storms and hurricanes, which can dump tremendous amounts of rain as they move inland. It also experiences frequent thunderstorms, with the Gulf Coast averaging 70 to 80 days per year with thunder.

Perhaps most notably, Alabama is a significant part of “Dixie Alley,” a region notorious for severe tornadoes. According to National Climatic Data Center statistics, Alabama, alongside Oklahoma and Iowa, has recorded the most confirmed F5 and EF5 tornadoes of any state since 1950, leading to more tornado fatalities than any other state in the same period. The state was heavily impacted by the devastating 1974 and 2011 Super Outbreaks, the latter producing a record 62 tornadoes. This stark reality means Alabama experiences a unique, and dangerous, secondary tornado season in November and December, in addition to the typical spring peak, constantly reminding its inhabitants of the raw power of their natural environment.

From the echoes of cannon fire to the whir of aerospace engines, from the painful legacy of segregation to the triumphs of civil rights, Alabama’s story is one of relentless transformation and enduring spirit. Its landscape, too, tells a tale of ancient geology, lush biodiversity, and dramatic climatic forces. Understanding Alabama means appreciating this intricate mosaic of human struggle and natural grandeur, a dynamic Southern state constantly evolving beneath the “Heart of Dixie” and the “Yellowhammer State” monikers.”