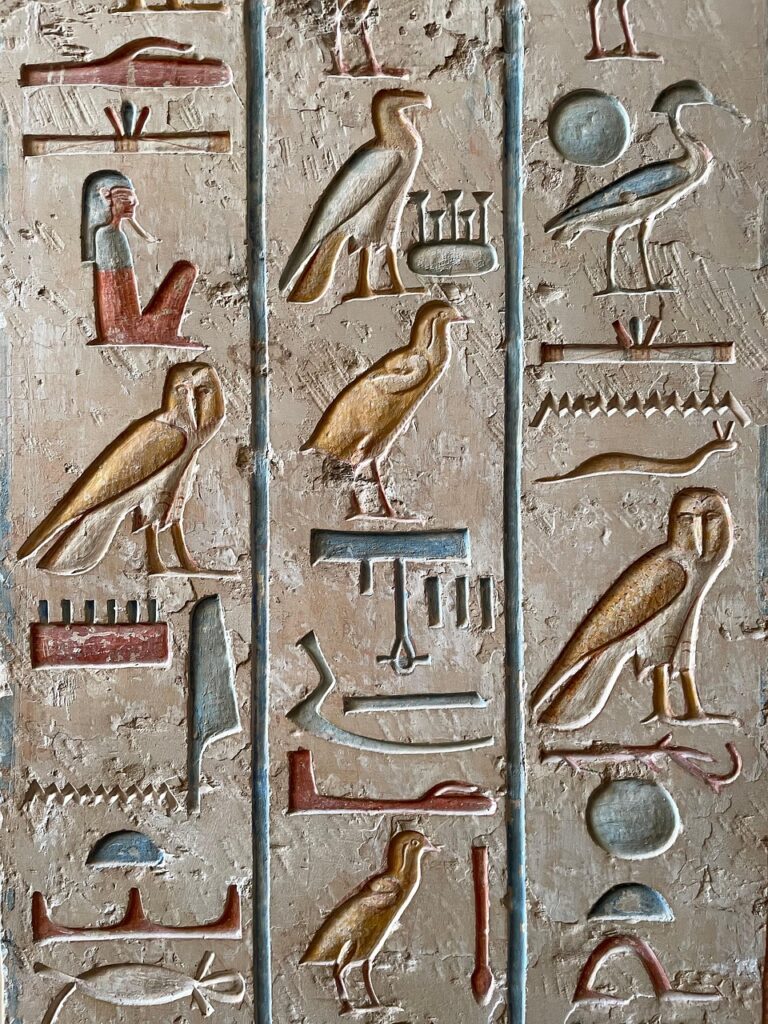

The ancient Egyptians, a civilization renowned for their monumental architecture, continue to leave us in profound awe with their incredible feats of engineering and craftsmanship. From the soaring pyramids that pierce the desert sky to the intricate temples that grace the banks of the Nile, their ability to transform raw stone into enduring testaments of power, belief, and artistic genius continues to challenge our understanding of ancient technology. These master builders worked with some of the hardest materials known to humanity – formidable basalt, resilient granite, unyielding quartzite, and dense diorite – often with tools that, at first glance, appear remarkably simple by modern standards.

How, then, did they achieve such breathtaking precision, monumental scale, and artistic finesse with what we traditionally consider rudimentary instruments? This question has captivated archaeologists, historians, and engineers for centuries, pushing the boundaries of conventional archaeological thought and inspiring countless theories. The answers, as we are continuously discovering, lie not just in brute force and sheer manpower, but in a profound understanding of geology, material science, and the ingenious application of physics, refined and passed down over millennia.

Join us on an extraordinary journey as we delve deep into the enigmatic world of ancient Egyptian stone cutting. We will uncover the groundbreaking techniques, puzzling discoveries, and hidden knowledge that continue to mystify and inspire, illuminating a deeper appreciation for the unparalleled ingenuity of these ancient craftsmen. Their legacy, literally carved in stone, defies the relentless march of time, standing as a testament to their enduring brilliance.

1. **The Enigma of Diamond-Drilled Cores**

One of the most profound and perplexing pieces of archaeological evidence challenging our understanding of ancient Egyptian stone cutting is the discovery of diamond-drilled cores. These intriguing artifacts, unearthed from various archaeological sites including the tomb of Prince Sabu in Saqqara and housed in the esteemed Petrie Museum, are far more than mere curiosities; they are silent witnesses to a technology that seemingly defies their era. Composed of hard stones like limestone, alabaster, and even granite, these cores bear distinctive spiral grooves that tell an astonishing story.

These grooves reveal a feed rate as remarkable as 0.100 inch per revolution—a pace that is, incredibly, 500 times greater than what can be achieved with modern diamond drills. This extraordinary finding compels us to fundamentally re-evaluate traditional beliefs regarding the tools available to the ancient Egyptians. For centuries, it was widely accepted that stones were shaped primarily using bow drills and copper tubes, augmented by abrasive sand. However, the presence of these diamond-drilled cores, with their undeniable precision and efficiency, strongly suggests that the ancient Egyptians had access to “cutting-edge drilling technology that surpassed modern methods.”

This revelation opens a Pandora’s Box of questions about the true extent of their scientific and engineering capabilities, implying a level of sophistication previously unknown to us. The implications of these diamond-drilled cores are far-reaching, providing concrete evidence of advanced drilling techniques employed to meticulously shape notoriously hard stones. The distinct spiral grooves observed on the cores are not just aesthetic marks; they are indicative of a highly efficient drilling process, a testament to an ingenious application of force and material science that puzzles even today’s experts.

To further explore this subject, we must consider the various theories attempting to explain the presence of these enigmatic cores. Some possibilities include “the use of diamond-coated drill bits,” suggesting a familiarity with extremely hard materials that could cut through granite with such precision. Another compelling theory “proposes that the Egyptians may have developed complex drilling machines that were capable of achieving high-speed rotation and feed rates, surpassing the capabilities of modern diamond drills.” While such theories offer potential explanations, the true origins and methods behind the diamond-drilled cores remain a vibrant subject of ongoing research and passionate debate, having “revolutionized our understanding of ancient Egyptian stone cutting techniques.”

2. **High-Performance Abrasives: Unlocking Corundum’s Role**

Beyond the mysteries of advanced drilling technology, another critical aspect of ancient Egyptian stone cutting that has long intrigued researchers is the nature and composition of the abrasives they employed. For a considerable period, the specific type of abrasive material used remained a topic of fervent debate among Egyptologists and historians. Some scholars initially suggested the use of emery abrasive powder, well-known for its hardness. However, this theory faced skepticism and eventual dismissal, largely due to “the absence of direct evidence and the presence of quartz sand in ancient drill holes,” which seemed to contradict the emery hypothesis.

Yet, the relentless pursuit of knowledge through modern scientific investigation has begun to shed groundbreaking new light on this very matter. A pivotal moment came with the meticulous analysis of a stone fragment originating from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This examination yielded a remarkable discovery: the fragment “revealed the presence of corundum, a mineral known for its high hardness,” found in a complex mixture with other minerals such as quartz, rutile, and feldspar. This finding was a true game-changer, indicating that the ancient Egyptians indeed “did have access to high-performance abrasives,” directly challenging and overturning previous long-held assumptions.

The identification of corundum, which is second only to diamond in hardness among natural minerals, profoundly alters our understanding of the ancient Egyptians’ material science and resourcefulness. This “corundum-rich abrasive material” would have been exceptionally effective in cutting and shaping the extremely hard stones they favored for their monumental projects. The exact geographical “source of these abrasives is yet to be determined,” adding another layer of intrigue to the story, though possibilities like “byproducts from mining gem-sized crystals or alternative corundum deposits such as the one located in Hafafit, Egypt” are being explored.

These compelling findings are not merely academic; they fundamentally “challenge our understanding of ancient Egyptian stone cutting techniques and highlight the advanced materials available to them.” The ability to procure and utilize such a potent abrasive would have been crucial in achieving the smooth, precise cuts and intricate details that characterize so much of ancient Egyptian stonework, particularly when coupled with softer copper tools. It suggests a sophisticated knowledge of mineral properties and a supply chain capable of providing these specialized materials, further demonstrating their innovative approach to construction.

3. **Dolerite Pounders and Early Quarrying**

While the discovery of advanced drilling and abrasive technologies points to a sophisticated understanding, the bedrock of ancient Egyptian stone working undoubtedly lay in simpler, yet incredibly effective, hand tools. Among the most fundamental were the “hand-held stone dolerite pounders.” These durable, ball-shaped stones were the primary instruments used for the arduous task of quarrying and initially shaping some of the hardest stones in the Egyptian palette, including formidable basalt, resilient granite, unyielding quartzite, and dense diorite. Their efficacy lay in their sheer hardness, allowing them to repeatedly strike and wear away at resistant rock surfaces.

A prime example that vividly showcases the sheer scale and challenge faced when using these tools is the magnificent “unfinished obelisk in Aswan.” Had it been completed, this colossal monument would have stood an awe-inspiring “42 meters tall and weighed around 1,200 tons,” a testament to the sheer ambition of ancient Egyptian builders. It is widely believed that these immense dimensions were to be shaped primarily through the diligent and relentless application of “round, hand-held stone dolerite pounders.” The distinct marks left on such sites provide direct archaeological evidence of their persistent use in detaching vast quantities of rock.

However, despite their undeniable utility, the context itself points out a crucial limitation: “these tools alone do not fully explain the precise shaping and horizontal striations observed on the walls of the obelisk.” This observation suggests that while dolerite pounders were instrumental for the initial removal of material and rough shaping, they likely were not the sole means by which the Egyptians achieved the remarkable precision and aesthetic finesse seen in their finished works. This nuance hints at a complementary set of techniques, or perhaps, as some experts “suggest that there may have been a civilization predating the dynastic Egyptians that possessed even more advanced stone-cutting technology.”

The extensive use of dolerite pounders speaks volumes about the sheer manpower and organizational capabilities of ancient Egyptian society. Quarrying massive blocks from their geological matrix was an undertaking of immense scale, requiring thousands of laborers working in synchronized effort under the scorching sun. The constant pounding, chipping, and breaking would slowly but surely detach large sections of rock, demonstrating a methodical and patient approach to monumental construction that laid the essential groundwork for their architectural wonders.

4. **Copper Saws and Sand Abrasion**

Moving beyond the blunt force of pounders, the ancient Egyptians also employed a more refined, yet still deceptively simple, method for cutting stone: the ingenious use of copper saws and drills. At first glance, the idea of using copper, a relatively soft metal, to cut through much harder stones like granite might seem paradoxical. However, the true ingenuity of the ancient craftsmen lay not just in the tool itself, but in the intelligent and consistent application of an abrasive medium. This technique is often referred to as “sand abrasion,” and it was a cornerstone of their stone-cutting prowess.

The process involved pairing copper saws and drills with loose “sand, which contains quartz,” a mineral significantly harder than copper. When the copper tool was moved back and forth or rotated against the stone, a constant supply of wet sand was introduced into the cutting interface. It was these harder quartz particles, suspended in the slurry, that actually did the abrasive work, slowly but surely “wearing through the stone” along the desired path. The copper blade merely served as an effective carrier and guide, applying the necessary pressure to the abrasive particles.

Compelling evidence for this precise technique comes from archaeological findings, particularly the “unfinished sarcophagus housed in the Cairo Museum.” This invaluable artifact, left in an incomplete state, offers a unique and illuminating “snapshot of the ancient Egyptian stone-working process.” Visible “tool marks on the sarcophagus align with the known use of copper saws and drills,” providing direct, tangible proof of their application. These marks clearly “indicate a gradual, methodical cutting process, supplemented by the use of abrasive sands.”

The technique of hollowing out a sarcophagus, as evidenced by this unfinished piece, further illustrates their methodical approach to intricate tasks. It “involved drilling a series of closely spaced holes along the desired cut line.” Once these initial holes were established, they “would then be connected by sawing, eventually removing the interior block of stone.” This systematic method demonstrates a remarkable understanding of how to work with the material, breaking down a complex task into manageable, sequential steps that maximized efficiency.

Despite the “rudimentary nature of their tools,” the “precision and skill evident in the sarcophagus are remarkable.” The ability to achieve “straight lines and smooth surfaces” using such a method speaks volumes about the high level of craftsmanship and a deep intuitive understanding of the material properties of stone. The copper saw with sand abrasion was a testament to their innovative problem-solving, enabling them to achieve cuts that would otherwise be impossible with the soft metal alone, leaving an enduring legacy of refined stonework.

5. **The Power of Water and Wooden Wedges**

Among the ancient Egyptians’ array of ingenious stone-cutting techniques, one of the most remarkable involved harnessing the subtle yet immense power of a seemingly simple element: water, in combination with humble wooden wedges. This method, often employed for quarrying and splitting exceptionally large stone blocks, showcased a sophisticated understanding of natural forces and material properties. It was a primary technique for separating massive pieces of granite and other hard stones along predetermined lines, making possible the extraction of the colossal blocks seen in their monumental architecture.

The process began with the meticulous creation of strategic holes or deep cracks along the intended splitting line within the granite block. These preparatory channels were carefully crafted using bronze or iron tools, ensuring precise placement. Once these access points were established, “wooden wedges” would be purposefully “driven into these holes and soaked with water.” The choice of wood was crucial, as different types absorb water at varying rates, thus exerting different pressures upon expansion.

The true genius of this technique lay in the hydraulic pressure generated. As “the wood absorbed moisture and expanded,” its volume increased significantly within the confined space of the drill holes or cracks. This gradual yet immense expansion “exerted a significant force,” a slow but incredibly powerful internal pressure that would eventually cause “the granite to split along predetermined lines.” This method allowed for a remarkably controlled fracture, guiding the natural cleavage of the stone with surprising accuracy.

Archaeological evidence robustly supports the widespread application of this technique, particularly in ancient Egyptian quarries. Workers would “identify existing cracks or fissures” within the rock face and strategically place these “wedges to encourage controlled splitting.” This method was especially effective when dealing with “massive blocks in quarries,” where precision in extraction was paramount to minimizing waste and maximizing the usable stone yield for their ambitious construction projects.

This ingenious application of water and wood stands as a powerful reminder that ancient technology was not always about complex machinery, but often about an acute observation and masterful manipulation of natural phenomena. It highlights a profound knowledge of the materials at hand and an ability to leverage their intrinsic properties to overcome what would otherwise be insurmountable challenges, allowing them to shape the very landscape to their architectural vision.

Read more about: Get Ready to Cook! These 14 Viral TikTok Recipes Took 2024 by Storm and Are Way Easier Than You Imagine!

6. **Basic Hand Tools of the Stonecutters**

The grandeur of ancient Egyptian monuments often, perhaps deceptively, obscures the fundamental fact that their construction relied heavily on the tireless efforts of countless artisans wielding what appear to be surprisingly simple hand tools. These fundamental instruments, meticulously refined over millennia, formed the indispensable backbone of their stone-working capabilities. The most ubiquitous and essential among these was the “stone hammer,” crafted from various hard stones like dolerite, and later, from bronze and iron as metallurgical knowledge advanced. These hammers varied considerably in size, from small, palm-sized tools ideal for detailed carving to “larger mauls for rough shaping” and initial quarrying.

Equally indispensable were chisels, which underwent a similar evolution from “copper to bronze and eventually iron.” These precision tools were designed for specific tasks: “Point chisels were used for initial rough cutting and removing large sections of stone,” aggressively breaking down material where necessary. In stark contrast, “flat chisels allowed workers to create smoother surfaces and more precise cuts,” enabling the detailed finishing work that characterizes Egyptian art with remarkable finesse. To provide optimal control and mitigate the risk of damaging the stone during striking, these chisels were typically “struck with wooden mallets,” a technique still valued by modern sculptors for its tactile feedback.

Picks served a dual purpose in the ancient stone worker’s arsenal. “Heavy picks were used to create initial trenches and separate blocks from quarry faces,” leveraging their weight and sharp points to dislodge substantial amounts of rock from its matrix. Meanwhile, “lighter versions helped in detailed shaping work,” allowing for more nuanced material removal and refinement of forms. Complementing these primary cutting and shaping tools were “wedges and levers,” often fashioned from sturdy “wood or metal,” which were crucial for “splitting stones along natural faults or cut lines,” as we have seen in the effective water-soaked wedge technique.

The ability to achieve the remarkable precision seen in ancient structures without modern measuring devices points to the sophistication of their “measuring and marking implements.” These included fundamental tools such as “plumb bobs” for ensuring vertical alignment, “squares” for establishing perfect right angles, and “scribing tools” for marking out intricate designs and precise cut lines. While “seemingly primitive by today’s standards,” these instruments were wielded with such mastery that they “enabled ancient craftsmen to achieve remarkable precision in their work,” leaving behind a legacy of perfectly aligned and seamlessly joined stonework that continues to impress engineers and architects worldwide.

7. **Specialized Cutting Implements**

As ancient stone working evolved and the demands of monumental architecture grew, so too did the complexity and specialization of the tools employed. Beyond the fundamental hammers and basic chisels, ancient civilizations, particularly the Egyptians, developed an impressive array of “specialized cutting implements” meticulously designed to tackle specific, often intricate, stone-working tasks. These tools reflect a continuous innovation aimed at increasing efficiency, precision, and the aesthetic range of their architectural and sculptural endeavors.

Among these specialized tools were the bronze and later iron chisels, which were crafted with “varying tip shapes, each serving a distinct purpose.” Pointed chisels remained essential for “initial rough cutting and creating guide lines,” acting as the primary aggressors against the stone’s raw surface. However, “flat-faced chisels enabled smoother, more controlled cuts,” providing the means to refine surfaces and achieve geometric accuracy after the initial roughing-out phase, making the transition from crude block to sculpted form.

A particularly innovative tool that increased efficiency was “the toothed chisel, featuring multiple sharp points along its edge.” This clever design “allowed craftsmen to create textured surfaces and remove material more efficiently than single-point tools.” It was an excellent choice for broad, shallow removal of material, leaving a characteristic pattern often desired for certain architectural finishes. For the extremely “precise detail work, especially in softer stones like limestone and marble,” ancient artisans employed “fine-tipped marking tools called tracers” to meticulously “outline intricate designs before deeper cutting began,” ensuring accuracy even in the most delicate carvings.

Another remarkable implement, crucial for creating specific architectural elements and features, was “the bow drill.” This ingenious device “consisted of a wooden frame, string, and a hardened copper or bronze bit.” It was “crucial for creating holes and cylindrical cuts in stone,” a technique vividly evident in the hollowed-out sections of various artifacts and structural components discovered. The continuous, rotary motion facilitated by the bow string allowed for consistent drilling, especially when combined with appropriate abrasives.

Even seemingly basic tools like “the pickaxe and pointed hammer” were not static in their design; they “were refined over centuries to achieve optimal angles and weights for different stone types.” These specialized variations were “essential for quarrying and rough shaping before finer implements were used to achieve the final form. Finally, to achieve the desired surface quality and intricate details, craftsmen also “developed specialized rasps and files, often embedded with copper or bronze teeth, for smoothing and finishing stone surfaces to remarkable precision,” completing the arduous journey from raw block to polished masterpiece.”

Read more about: Equipping Your Vehicle: The Essential Guide to Surviving Roadside Breakdowns and Unexpected Hazards

8. **Splitting and Cleaving: Advanced Methods**

Beyond the straightforward application of water-soaked wooden wedges, ancient stone workers developed even more refined techniques for splitting and cleaving massive stone blocks. This process relied heavily on a profound understanding of the stone’s inherent characteristics, including its natural cleavage planes and any existing weak points. Craftsmen would meticulously examine the grain and internal structure of a stone to identify these natural splitting lines, turning geological features into an advantage.

One particularly effective method involved the creation of a series of precisely aligned holes along the intended splitting path. While bronze or iron tools were used to bore these initial channels, the real innovation came with the introduction of metal wedges, often accompanied by thin metal strips known as “feathers.” These feathers were placed on either side of the wedge before it was inserted, helping to distribute pressure evenly and protect the stone.

Workers would then drive these metal wedges simultaneously and in a coordinated manner, applying strikes with hammers. The synchronized impact, combined with the expanding pressure from the wedges, would create controlled fractures within the stone. This method offered significantly greater control over the splitting process compared to less systematic approaches and proved exceptionally effective when dealing with notoriously harder stones like granite, allowing for more predictable and cleaner breaks.

In ancient Egyptian quarries, archaeological evidence further indicates that while they identified existing cracks, they also strategically placed wedges to encourage controlled splitting. This targeted approach was crucial for extracting massive blocks from their geological matrices, ensuring that the precious material was removed with minimal damage and maximum yield. These ingenious ancient methods for splitting stone continue to inform and influence modern quarrying practices, despite the advent of advanced machinery.

9. **Precise Shaping Methods: Beyond the Basics**

Achieving the remarkable geometric accuracy and intricate forms seen in ancient stone structures required methods far more sophisticated than simple cutting. Ancient civilizations, especially the Egyptians, honed a variety of precise shaping techniques for their monumental blocks and detailed architectural elements. These methods allowed them to transition from raw quarried stone to the finished, often ornately carved, forms.

One such intricate technique was called *pointillage*, a meticulous process where craftsmen used pointed tools to gradually chip away at the stone’s surface in a highly controlled manner. This method was particularly effective for creating the detailed sculptural elements and precise geometric shapes that adorn temples and tombs. It was a painstaking labor of love, building up the form by tiny, incremental removals of material.

For achieving exceptionally straight and precise cuts, especially in challenging materials like granite, the ancient Egyptians mastered the use of copper saws in conjunction with abrasive sand. This technique involved continuously introducing wet sand into the cutting area, where the hard quartz particles within the sand acted as primitive cutting teeth. The copper blade merely guided the sand, which slowly but surely wore away the stone along the desired path, leaving remarkably clean and linear cuts.

Another sophisticated, albeit labor-intensive, method involved using bronze wire combined with abrasive materials. Workers would pull this wire back and forth across the stone while continually adding a slurry of sand and water. This essentially created a primitive wire saw, allowing for deeper cuts and the creation of more complex shapes in very large stone blocks. The continuous friction and abrasion, guided by the wire, slowly abraded the stone away.

Crucially, archaeological evidence confirms that many ancient cultures utilized templates and various marking tools to ensure consistency and accuracy in their stone-cutting work. This demonstrates an advanced understanding of geometry and dimensional precision, allowing them to replicate designs and ensure that individual blocks fit together seamlessly within grander architectural schemes.

10. **The Art of Surface Finishing**

Once stone blocks were cut and shaped, ancient craftsmen turned their attention to the crucial process of surface finishing, which served both practical and aesthetic purposes. The desired finish could range from a utilitarian rough texture to a dazzling, mirror-like polish, each contributing to the monument’s overall appearance and durability. This stage often involved multiple steps and different abrasive materials.

Grinding was the most common finishing method, where artisans meticulously used abrasive stones of varying grits to smooth down rough-cut surfaces. The process typically began with coarse, rougher materials to remove prominent tool marks and gradually progressed to finer and finer abrasives. This systematic approach gradually created an increasingly smooth surface, preparing the stone for further refinement or its final placement.

For specific decorative elements or to achieve a particular architectural texture, specialized techniques like bush hammering were employed. This involved repeatedly striking the stone surface with a multi-pointed hammer, creating a distinctive textured, stippled appearance. This technique was particularly popular in Egyptian and Greek architecture, providing not only visual interest but also improved grip on walking surfaces, demonstrating a thoughtful blend of form and function.

Polishing was reserved for the most exquisite architectural elements and sculptural masterpieces. Craftsmen would painstakingly use natural abrasives such as fine sand mixed with water, followed by even finer materials like pumice, and ultimately, soft materials like leather strops. The ultimate goal was the astonishing, mirror-like finish seen on many ancient Egyptian granite monuments, a testament to immense skill and patience.

The ancient Romans, building upon these traditions, pioneered the use of different surface treatments on a single piece of stone. They skillfully combined polished and textured areas to create striking visual contrast, which effectively emphasized architectural features and added another layer of artistic sophistication to their structures. Some surfaces, for particular effects or to highlight the stone’s natural character, were even intentionally left rough or “quarry-faced,” demonstrating a full command over the material’s potential.

Read more about: Beyond the Popcorn: 14 Infamous Movies That Sent Audiences Running for the Exits

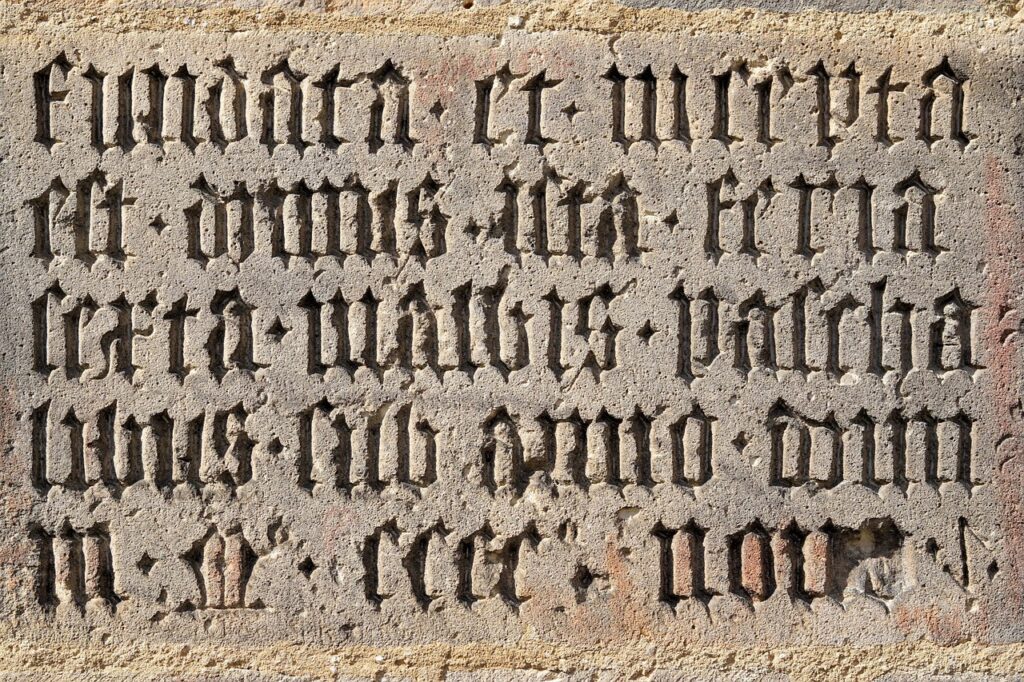

11. **Greek and Roman Innovations in Stone Working**

The Greeks and Romans, while undeniably influenced by earlier Egyptian prowess, significantly revolutionized stone cutting techniques through systematic innovation and their distinct engineering genius. Their contributions dramatically improved the efficiency and precision of stone extraction, shaping, and finishing, setting new standards for the ancient world and beyond.

Roman engineers, in particular, made strides by introducing the widespread use of iron wedges and applying advanced leverage principles to split massive stone blocks. They refined a technique known as the “wedge and feather” method. This involved drilling a series of holes along a predetermined splitting line and then inserting metal wedges, often iron, paired with thin metal “feathers” into these holes. When struck simultaneously and with coordinated force, these wedges created controlled fractures, leading to more precise extraction than the earlier methods that often relied on natural stone weaknesses alone.

The Romans also perfected the art of sawing stone on an unprecedented scale, utilizing large bronze or iron saws in combination with abrasive sand. This critical innovation enabled them to produce thinner, more uniform stone slabs, which became essential for a vast array of construction projects and decorative applications across their sprawling empire. Their ceremonial stone cutting traditions often integrated these advanced techniques, allowing for the creation of incredibly elaborate architectural elements and monumental sculptures.

Greek stoneworkers, in turn, contributed significantly by developing specialized chisels and points tailored for highly detailed carving. They were pioneers in understanding and utilizing different grades of abrasives for polishing stone surfaces, particularly their beloved marble. This refined approach allowed them to achieve unprecedented levels of smoothness and luster in their marble works, creating the iconic, exquisitely finished sculptures and architectural details that define classical Greek art. Their deep intuitive understanding of stone’s natural properties also led to innovative quarrying methods that minimized waste and maximized resource utilization.

These classical innovations from the Greeks and Romans laid robust groundwork for many stone-working techniques that remain relevant even today. Their enduring impact on modern stone craftsmanship is undeniable, demonstrating how their refined approaches to materials and engineering principles continue to inspire and inform contemporary practices.

Read more about: Why the U.S. Navy’s Fastest Ship Can’t Hunt Submarines: An In-Depth Look at ASW’s Enduring Technical Hurdles

12. **Thermal Mass and Sustainable Legacy**

One of the most remarkable, yet often overlooked, aspects of ancient stone-working extends beyond mere structural integrity to the sophisticated environmental engineering embedded within their architectural designs. The sheer thermal mass properties of the massive stone blocks used by ancient civilizations, especially the Egyptians, allowed them to create structures that were naturally climate-controlled. This represented an ingenious, passive approach to temperature regulation that is highly admired today.

By examining the precision-cut granite blocks of ancient Egyptian monuments, one can appreciate how these structures inherently offered cooler interiors in blistering desert heat and retained warmth during cooler nights. The immense volume and density of the stone absorbed and slowly released thermal energy, creating stable internal temperatures. This sophisticated understanding of material science meant their buildings were not just robust, but also sustainable, minimizing energy consumption for heating and cooling long before such concepts were formally articulated.

The sustainable approaches employed by these ancient master builders offer invaluable lessons for contemporary architecture. Their methods minimized waste through careful quarrying and precise fitting, demonstrating an inherent respect for resources. The longevity of their stone structures, often standing for millennia, is a testament to the durability achieved through quality craftsmanship and a profound understanding of material properties, principles that resonate deeply with modern sustainable construction movements.

Understanding these historical techniques not only reveals how ancient craftsmen achieved extraordinary precision that continues to challenge conventional archaeological timelines but also inspires contemporary applications. The principles of thermal mass and passive climate control, once intuitively applied, are now consciously studied and integrated into modern green building design, proving the timeless wisdom of ancient engineering.

These ancient methods, from selecting local materials to designing for natural ventilation and thermal regulation, serve as powerful reminders that sustainable building is not a modern invention but a revival of principles perfected by civilizations long past. The legacy of their climate-controlled structures continues to offer blueprints for ecological design in the present day.

Read more about: The Revival Circuit: 12 Forgotten Concepts That Changed the Automotive Industry

13. **The Enduring Impact: Modern Lessons from Ancient Masters**

The wisdom of ancient stonemasons continues to profoundly influence and guide modern construction and design practices, proving that while tools evolve, fundamental principles often remain timeless. Despite today’s craftsmen having access to advanced tools and technology, many core tenets established thousands of years ago continue to hold immense relevance in the contemporary world, underscoring the enduring value of traditional stone working practices.

Ancient craftsmen’s deep understanding of stone’s natural properties—its bedding planes, fault lines, and inherent strengths—directly informs contemporary quarrying methods. Their technique of following these natural characteristics not only significantly reduces material waste but also yields stronger, more stable finished products. This approach exemplifies a commitment to resource conservation and structural integrity that modern sustainable construction actively strives to emulate, showcasing a timeless environmental consciousness.

Furthermore, the ancient practice of hand-dressing stone surfaces offers invaluable lessons in creating unique textures and finishes that machine-cutting simply cannot replicate. The subtle nuances and artisanal character of hand-finished elements are increasingly sought after in high-end architectural projects today. Such endeavors often blend modern precision with traditional artistry to achieve distinctive and visually rich results, honoring the craft of ages past.

Ancient builders’ unparalleled expertise in joint design and stone placement continues to inform and inspire modern construction techniques. Their ingenious methods of fitting massive stones together without mortar, as marvelously demonstrated in structures like Machu Picchu, highlight a superior understanding of weight distribution and structural stability. These principles are particularly invaluable in contemporary seismic-resistant architecture, offering blueprints for resilience in challenging environments.

Perhaps most significantly, the ancient masters’ approach to tool design, constantly refining instruments for optimal performance with specific materials, continues to influence modern stone working equipment. The basic principles behind ancient chisels and hammers remain strikingly evident in today’s pneumatic tools, albeit executed with far greater precision and efficiency. Even modern diamond-tipped cutting tools follow patterns of wear and effectiveness first observed and understood by ancient craftsmen, cementing the enduring legacy of their innovation. Understanding these historical techniques allows modern stone workers to gain a deeper appreciation for their material’s intrinsic properties and limitations. This profound knowledge continues to shape innovative approaches to stone cutting and construction, powerfully demonstrating that sometimes, the old ways truly do provide the strongest foundation for new and groundbreaking advances.

These ancient civilizations achieved engineering marvels through stone cutting techniques that continue to mystify modern experts. From the precise angles of Egyptian pyramids to the seamless joints of Incan walls, these master craftsmen shaped massive stone blocks with remarkable accuracy using surprisingly simple tools. The cultural significance of marble and other stones drove innovation across civilizations, leading to sophisticated methods that combined raw manpower with ingenious mechanical advantages.

Archaeological evidence reveals a fascinating toolkit: copper saws with sand abrasives, wooden wedges soaked in water, and stone hammers that could split massive blocks along natural faults. These fundamental techniques, refined over millennia, laid the groundwork for modern stone working practices. While today’s craftsmen benefit from diamond-tipped tools and hydraulic machinery, they still rely on principles discovered by ancient stonecutters who understood the inherent properties of stone and how to work with, rather than against, nature’s most enduring building material. Through careful study of ancient quarries and unfinished works, we continue to uncover the brilliant solutions our ancestors developed to overcome seemingly impossible architectural challenges. The awe and inspiration these structures evoke are a timeless reminder of human ingenuity, inviting us to look back not just to learn, but to find guidance for the challenges of tomorrow.”

, “_words_section2”: “1994

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(737x230:739x232)/Multiretailer-Celebrity-Track-Pants-011325-01-c9599cb19b91422c9c4840253f7f3c92.jpg)