The American automotive landscape, often romanticized as a symbol of freedom and individual mobility, is, upon closer inspection, a complex tapestry woven with intricate classifications and regulatory definitions. These categorizations, set forth by various governmental and independent bodies, subtly delineate roles, expectations, and even societal standing. From the Environmental Protection Agency’s meticulous volume metrics to the initial classifications of light trucks, each system carves out segments of the vehicle population, inadvertently reflecting the diverse—and often divided—economic and social strata of the nation.

These seemingly innocuous bureaucratic guidelines, designed for emissions control, fuel economy, safety, and infrastructure planning, paint a nuanced picture of America’s vehicular ecosystem. The multiplicity of classification approaches—by interior volume, gross vehicle weight rating (GVWR), curb weight, or axle count—underscores a fragmented reality. This fragmentation, viewed through a socio-economic lens, hints at underlying class divisions, manifesting in the types of vehicles Americans choose, afford, and operate. The choice between a subcompact and a large SUV, while personal, is often constrained or informed by broader economic realities, echoing deeper societal patterns.

In this exploration, we delve into the multifaceted world of American vehicle classification, unpacking how these technical demarcations function as implicit indicators of class division. By examining the precise criteria used by entities like the EPA, we can discern how different segments of the population are served by distinct categories of automobiles. This isn’t just about statistics; it’s about understanding how the very definitions of our vehicles mirror the aspirations, necessities, and inequalities that characterize the American experience.

1. EPA Passenger Car Classes: Volume as a Marker of Class*

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) classifies passenger cars based on interior volume index. Federal Regulation, Title 40—Protection of Environment, Section 600.315-08, categorizes sedans into Minicompact (< 85 cubic feet), Subcompact (85–99.9 cubic feet), Compact (100–109.9 cubic feet), Mid-size (110–119.9 cubic feet), and Large (≥ 120 cubic feet). This hierarchy signifies increasing interior space, often correlating with vehicle price, comfort, and luxury.

This volume-based hierarchy reflects a spectrum of needs and economic capacities. “Minicompact” cars cater to drivers for whom space is less a priority or cost-efficiency paramount. They serve as entry points into car ownership, favored by urban dwellers or those with tighter budgets, where interior volume trades off against acquisition and running costs.

Conversely, “Large” passenger cars, with 120 cubic feet or more, represent a different echelon. Offering expansive comfort and advanced features, commanding such a vehicle implies a distinct economic reality. Here, space, comfort, and status often supersede immediate frugality, reinforcing economic divisions where larger vehicles signify greater affluence.

2. EPA Station Wagon Classes: Utility and Economic Realities

The EPA classifies station wagons by interior volume: “Small” (< 130 cubic feet), “Midsize” (130–159 cubic feet), and “Large” (≥ 160 cubic feet). Blending car-like dynamics and cargo capacity, these highlight how utility and space are scaled commodities in American households, revealing societal patterns.

The “Small” station wagon, with modest interior volume, appeals to buyers seeking practical utility without the bulk of a larger SUV, or those needing more space than a sedan but mindful of budget. This suits families prioritizing versatility and efficiency, where function meets economic constraints.

“Midsize” and “Large” wagons signify a shift. Offering significantly more room, these align with families requiring substantial space for daily life. Greater capacity often correlates with lifestyle and economic stability. This distinction reflects differing demands on personal space and resources, echoing class-based consumer patterns.

3. EPA Truck Classes: The Foundational Small Pickup

The EPA classifies trucks by Gross Vehicle Weight Rating (GVWR). “Small pickup trucks” are defined by a GVWR of less than 6,000 pounds (2,700 kg). This category embodies a quintessential American vehicle, associated with labor, utility, and a less ostentatious lifestyle, serving as a backbone for economic sectors.

The “Small pickup truck,” by design, is a tool for businesses or individuals needing a capable vehicle for hauling and work. Its smaller stature and GVWR often mean lower purchase price and better fuel economy, making it accessible for those whose livelihoods depend on robust transport within tighter financial margins.

Focused on functionality and economic accessibility, the “Small pickup truck” often occupies a different social stratum than luxurious options. It represents a segment valuing durability and direct utility over opulent features. Its classification highlights a distinction between vehicles for vocational necessity and those for broader lifestyle or status, underscoring economic divisions.

4. EPA Truck Classes: The Ascendant Standard Pickup

“Standard pickup trucks” represent a more robust segment within the EPA’s GVWR-based truck classifications (6,000 to 8,500 pounds). These vehicles signify escalation in capability, status, and cost, bridging pure work vehicles and those increasingly used for personal transport and leisure, reflecting shifting American preferences.

The “Standard pickup truck” is a cultural phenomenon. While retaining core utility for hauling and towing, many now feature amenities once exclusive to luxury sedans. This dual nature serves as essential tools for trades and as primary family vehicles for commuting and adventures, catering to diverse activities.

Their broad appeal and sophistication highlight a complex class dynamic. For some, they are indispensable for demanding work; for others, they embody a lifestyle choice—offering safety, command, and rugged independence—often with a higher price tag. This highlights the economic wherewithal for either the essential workhorse or upscale family hauler.

5. EPA Truck Classes: The Essential Minivan

Minivans occupy a unique segment within EPA’s truck classifications, defined by a GVWR of less than 8,500 pounds and designated for passenger transport. Unlike pickups or many SUVs, minivans prioritize family utility: passenger comfort, extensive cargo space, and sliding door access. Their classification reflects a particular demographic and distinct needs.

Minivans emerged as a solution for growing families, offering unparalleled interior volume, versatile seating, and a lower loading floor than many SUVs. Their design emphasizes practicality, safety, and convenience for transporting children and gear, making them ideal for family logistics. This focus means minivans are purchased by households prioritizing functionality and safety.

While lacking the rugged image of an SUV or luxury of a large sedan, minivans’ utility to a significant population is undeniable. They represent an economic choice by families requiring maximum space and convenience, often operating within budgets prioritizing value and practicality. The minivan subtly symbolizes a specific American household focused on family logistics and efficiency.

6. EPA Truck Classes: The Diverse SUV Landscape

The EPA classifies Sport Utility Vehicles (SUVs) as trucks, divided into “Small” (< 6,000 lbs GVWR) and “Standard” (6,000–10,000 lbs GVWR) since 2013. This reveals American class division, as SUVs evolved from utilitarian roots into a popular, varied segment, from compact crossovers to luxury behemoths, catering to diverse desires and economic capacities.

The “Small Sport Utility Vehicle” category often includes crossover SUVs, blending car-like dynamics with higher ride height and cargo flexibility. These appeal to a broad demographic, including younger families and urban dwellers, seeking security and versatility without the full bulk or fuel consumption of larger SUVs. They represent an accessible entry point into the SUV market, serving as a practical and affordable choice for many households.

“Standard Sport Utility Vehicles” typically signify larger, more capable, and often more expensive machines. With higher GVWR, they offer greater towing capacity, extensive off-road capabilities, and significant road presence. Associated with higher income brackets or individuals prioritizing prestige and spaciousness, the distinction reflects a clear economic divide, highlighting how different Americans navigate aspirations within this expansive category.

7. NHTSA Passenger Car Classes: Weight as a Divisive Metric

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), with its focus on vehicle safety, employs a distinct classification system, grouping cars for NCAP testing primarily by weight. This approach shifts the lens from interior volume, which hints at comfort and amenities, to curb weight—a metric intimately tied to vehicle construction, material use, and often, cost and perceived safety. NHTSA categorizes passenger cars into ‘mini’ (1,500–1,999 lbs.), ‘light’ (2,000–2,499 lbs.), ‘compact’ (2,500–2,999 lbs.), ‘medium’ (3,000–3,499 lbs.), and ‘heavy’ (3,500 lbs. and over). This weight-based stratification implicitly introduces another dimension to America’s class divisions, where the literal heft of a vehicle can signify differing levels of protection and investment.

The lightest categories, ‘mini’ and ‘light’ passenger cars, often represent the most economical options on the market. These vehicles typically have smaller footprints and less robust construction compared to their heavier counterparts. While engineering advancements have made even small cars safer, the inherent physics of a collision often favor the heavier vehicle. This reality means consumers in lower income brackets, who frequently gravitate towards these more affordable, lighter cars, may be unconsciously opting into a statistically higher risk profile in certain types of accidents. This forms a stark, if unspoken, class-based disparity in potential safety outcomes.

Moving up the NHTSA weight ladder, ‘compact,’ ‘medium,’ and ‘heavy’ passenger cars typically correlate with higher price points and more extensive safety features. A heavier vehicle not only offers a greater mass advantage in a collision but often incorporates more advanced structural designs and protective technologies. The ability to afford a ‘heavy’ passenger car, therefore, often implies a greater capacity to invest in personal and familial safety, transcending basic transportation to secure a more fortified driving experience. This division underscores how economic stratification permeates even the fundamental promise of safety on American roads, where the ability to mitigate risk is, to some extent, a function of financial capacity.

The NHTSA’s system, though designed for safety testing, reveals how safety can become an indirect marker of class. The weight of a vehicle, an objective engineering parameter, translates into perceived and actual protection, which itself is not uniformly distributed across the population. It highlights a societal dynamic where access to advanced safety—often a byproduct of greater vehicle mass and more sophisticated engineering—becomes another privilege tied to socio-economic standing.

8. NHTSA Truck, SUV, and Van Classes: Specialized Utility and Perceived Safety

Beyond passenger cars, NHTSA’s classification extends to other crucial vehicle types: Sport utility vehicles (SUV), Pickup trucks (PU), and Vans (VAN). These segments are broad, acknowledging their distinct functional roles, but still carry implications for class. The very existence of these separate, robust categories within a safety-focused framework speaks to the American preference for larger, more versatile vehicles, which often offer a psychological and physical advantage in terms of perceived safety and utility. These aspects are deeply intertwined with lifestyle choices and economic capabilities.

SUVs, a ubiquitous presence on American roads, are recognized by NHTSA as a distinct class, indicative of their widespread adoption and the need for specialized safety considerations. Their higher ride height and substantial mass often provide occupants with a sense of security and command over the road, a feeling many buyers are willing to pay a premium for. This preference for SUVs, often fueled by marketing emphasizing adventure, family safety, and capability, often translates into significant financial outlay. This reflects a household’s economic ability to prioritize these attributes over, for instance, fuel efficiency or compactness.

Pickup trucks, similarly, stand as a separate NHTSA class, acknowledging their unique design and primary utility. While many pickups serve as indispensable tools for trades and labor, their growing sophistication and luxury options mean they also cater to a segment of consumers who desire both utility and prestige. The ability to own and operate a large pickup—often accompanied by higher fuel costs and maintenance—is a clear indicator of economic capacity, whether for demanding vocational use or as a statement vehicle for leisure activities. Their size and robust build often provide a protective envelope, an attribute valued across various class strata but afforded differently.

Vans, designated as another distinct class by NHTSA, particularly minivans, prioritize passenger capacity and ease of access. While perhaps lacking the rugged allure of an SUV or pickup, their classification by NHTSA affirms their role as essential family transporters. For many middle-class families, a van represents a practical, cost-effective solution for everyday logistics, embodying a pragmatic approach to vehicular needs rather than a pursuit of status. This highlights how even within safety classifications, different vehicle types cater to, and reflect, specific socio-economic needs and priorities, ranging from the aspirational to the purely utilitarian.

9. FHWA Functional Categories: Infrastructure and Economic Activity

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) introduces yet another layer of classification, developed in the 1980s, primarily for federal reporting requirements and as a basis for state vehicle classification systems. Its 13-category rule set moves beyond mere vehicle type or volume, instead focusing on ‘functional categories’ based on vehicle configuration, such as the number of axles. This system provides an invaluable lens through which to understand the vehicles that underpin America’s economic activity and infrastructure, implicitly mapping out the class divisions related to labor, commerce, and transportation.

The FHWA’s categories range from ‘Motorcycles’ (Class 1) and ‘Passenger cars’ (Class 2) to various permutations of ‘single-unit trucks’ (Classes 5-7) and ‘single-trailer trucks’ (Classes 8-10) and ‘multi-trailer trucks’ (Classes 11-13). ‘Other two-axle four-tire single-unit vehicles,’ including pick-ups and vans, also have their own category (Class 3). This detailed breakdown highlights the commercial and industrial backbone of the nation, vehicles indispensable for logistics, construction, agriculture, and service industries. The operators and owners of these vehicles, from independent truck drivers to large fleet companies, represent distinct economic segments, and their vehicles are tools of their trade, intrinsically linked to their livelihoods.

Class 2, encompassing ‘All cars’ including ‘Cars with one-axle trailers’ and ‘Cars with two-axle trailers,’ represents the personal mobility segment. Even here, the ability to own a car and attach trailers speaks to disposable income for leisure or specific hauling needs. However, the subsequent categories, dominated by trucks of increasing size and axle count, starkly differentiate between personal transport and commercial enterprise. A Class 9 ‘Five-axle single-trailer truck,’ for instance, is not a personal vehicle; it is a capital asset, representing a substantial investment and a livelihood. These heavy-duty classifications underscore the economic engine of the country, powered by professional drivers and logistics networks, revealing a foundational class of workers whose daily lives revolve around these massive machines.

The FHWA’s system, by cataloging vehicles according to their functional capacity and physical configuration, inherently maps the economic landscape. It distinguishes between vehicles for personal consumption and those for commercial production, reflecting the different roles individuals play within the economy. The sheer variety of truck classifications speaks to the specialization and scale of American industry and commerce, where the capabilities of a vehicle directly translate to economic opportunity and, by extension, class affiliation. This framework, while technical, provides a clear, albeit indirect, illustration of how vehicles are not just modes of transport, but instruments of economic stratification.

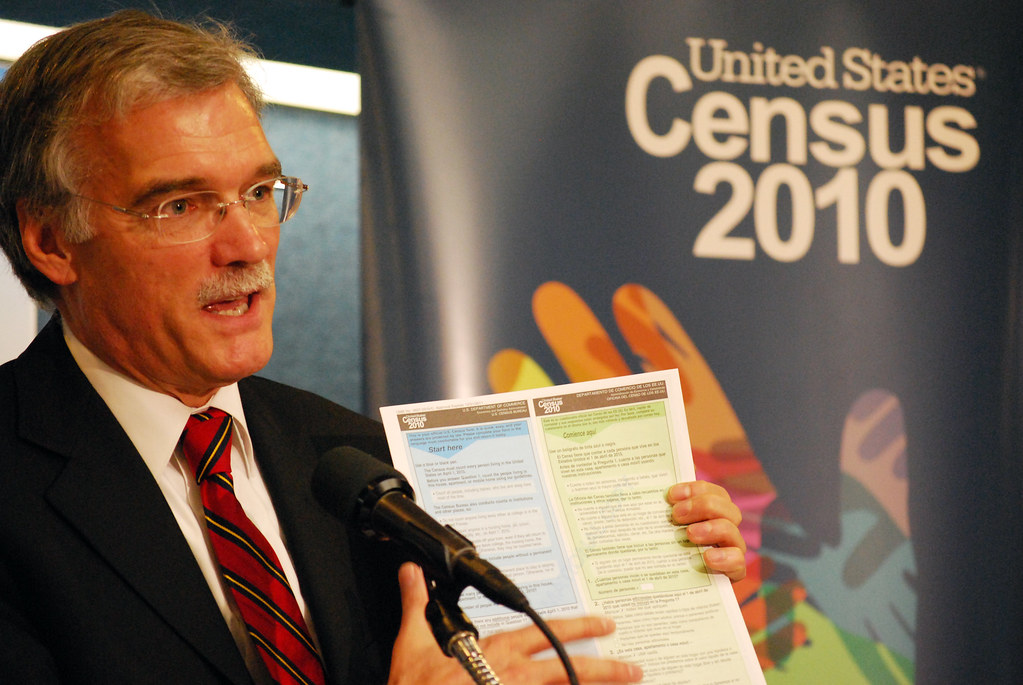

10. U.S. Census Bureau’s Truck Focus: Documenting the Working Vehicle

The U.S. Census Bureau’s approach to vehicle classification further narrows the focus, primarily concentrating on the truck population through surveys. This singular emphasis on ‘trucks’ for regulatory purposes—which notably include all pickups, vans, minivans, and sport utility vehicles, regardless of their unibody or body-on-frame construction—underscores a particular understanding of utility and function within the American vehicle fleet. By segmenting owners of ‘large trucks’ (NHTSA classes 4-13) for a standard survey and ‘small truck’ owners (NHTSA class 3, comprising pickups, vans, minivans, and SUVs) for a short survey, the Census Bureau implicitly recognizes differing socio-economic profiles and usage patterns.

This classification system, while seemingly administrative, reinforces a societal view of what constitutes a ‘working vehicle’ versus a ‘passenger car.’ The Census Bureau’s broad definition of ‘trucks’ for regulatory purposes, even encompassing many modern SUVs and minivans, reflects a practical acknowledgment of their often utilitarian roles, even if that utility is geared towards family transport rather than commercial hauling. It highlights that a significant portion of the American populace relies on vehicles that, by this definition, are not merely cars, but multi-purpose instruments central to their daily lives and, often, their livelihoods. This pragmatic categorization subtly distinguishes between vehicles primarily for personal leisure and those that perform essential, often labor-intensive, functions.

The distinction between ‘large truck’ owners, who receive a standard survey, and ‘small truck’ owners, who receive a shorter one, further hints at underlying economic differentiation. Owners of larger, heavier trucks (NHTSA classes 4-13) are more likely to be involved in commercial enterprises, where their vehicles are direct inputs to their income. These are often small business owners, farmers, or independent contractors whose financial well-being is intrinsically tied to their vehicle’s capabilities. The comprehensive survey likely delves into aspects of business operation, reflecting a more complex economic profile.

Conversely, ‘small truck’ owners, encompassing the broad category of pickups, vans, minivans, and SUVs (NHTSA class 3), might include a wider spectrum of the population, from tradespeople to suburban families. While these vehicles also serve essential functions, their survey brevity might suggest a focus on general household usage rather than extensive commercial application, implying a different economic context. The Census Bureau’s classification, therefore, while designed for data collection, acts as an ethnographic tool, delineating segments of the American population based on their reliance on, and the economic role of, their specific type of ‘truck,’ reinforcing the nuanced ways vehicle choice is entwined with class.

11. IIHS Safety-Oriented Size Classes: The Intersection of Safety and Affluence

The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) presents a vehicle classification system that directly impacts consumers’ wallets through insurance premiums, and critically, through perceived and actual safety. Grouping cars by curb weight and ‘shadow’ (exterior length multiplied by exterior width) into six classes—’micro,’ ‘mini,’ ‘small,’ ‘midsize,’ ‘large,’ and ‘very large’—the IIHS system draws a clear line between vehicle dimensions, mass, and crashworthiness. This technical framework has profound implications for understanding class division, as access to higher safety ratings and lower premiums is often a function of being able to afford larger, heavier vehicles, which statistically offer better protection in many crash scenarios.

The ‘micro’ and ‘mini’ classes, typically comprising the lightest and smallest vehicles, represent the entry point into car ownership for many. While modern engineering has improved the safety of these vehicles, the fundamental physics of a collision often put occupants of smaller cars at a disadvantage when encountering larger, heavier vehicles. This creates a challenging dynamic for those in lower income brackets, who frequently purchase these more affordable models. They might save on the initial purchase price and fuel costs, but potentially face higher risks in accidents and, ironically, often higher insurance premiums due to the greater likelihood of severe damage or injury in a collision, thus forming a cruel economic paradox.

As one ascends the IIHS hierarchy to ‘midsize,’ ‘large,’ and ‘very large’ vehicles, the curb weight and shadow dimensions increase substantially. These larger vehicles, often equipped with more advanced safety technologies and robust structures, generally offer superior crash protection. The ability to afford a ‘large’ or ‘very large’ vehicle, with its inherent safety advantages, directly reflects a greater economic capacity. This choice is not merely about space or features; it is an investment in safety that fewer can make, inadvertently widening the safety gap between socio-economic classes. The IIHS data, though empirically objective, illustrates how safety, a universal concern, is stratified by the economics of vehicle acquisition.

The IIHS system, by explicitly linking physical dimensions and weight to safety performance, uncovers a subtle but pervasive aspect of class division: the quantifiable difference in protection available to different economic strata. Insurance premiums, a tangible financial burden, are directly influenced by these classifications, further solidifying the economic impact. Consequently, choosing a vehicle is not merely a lifestyle decision; for many, it is a calculation of risk and affordability, where the car they can afford dictates the level of physical protection they can secure, thereby reinforcing the profound connection between automotive classification, economic status, and personal safety.

12. Canadian Classifications: Mirroring U.S. Divisions with Local Nuances

Across the northern border, Canada’s vehicle classification system largely mirrors that of the United States, especially due to shared automotive markets and designs. However, Natural Resources Canada’s Fuel Consumption Guide and the On-Road Vehicle and Engine Emission Regulations (SOR/2003-2) provide specific nuances. Canada classifies passenger cars into ‘Two-seater,’ ‘Subcompact,’ ‘Compact,’ ‘Mid-size,’ and ‘Full-size’ based on interior volume, similar to the EPA. Trucks, special purpose vehicles, and vans are segmented in their own respective classes. This parallel structure reinforces that economic and societal divisions, as reflected in vehicle choices, are not exclusively an American phenomenon but a broader North American one.

The interior volume-based classification for Canadian passenger cars suggests that Canadian consumers also experience a similar correlation between vehicle size, price, and perceived luxury or practicality. ‘Subcompact’ cars, with under 2,830 liters (99.9 cubic feet) of interior volume, likely appeal to budget-conscious buyers or urban dwellers, much like their U.S. counterparts. Conversely, ‘Full-size’ cars, with over 3,400 liters (120 cubic feet), represent a higher tier of comfort and expense, accessible to more affluent segments of the population. This volumetric scaling of vehicles thus serves as a reliable indicator of economic capacity and lifestyle priorities in Canada, echoing the dynamics observed in the U.S.

For trucks, Canadian regulations categorize them by GVWR, curb weight, and frontal area, into ‘Light light-duty truck,’ ‘Light-duty truck,’ ‘Heavy light-duty truck,’ and ‘Heavy-duty vehicle,’ with a specific ‘Medium-duty passenger vehicle’ class. These classifications distinctly separate commercial and heavy-duty applications from lighter personal use. A ‘Heavy-duty vehicle’ represents a significant investment, often a commercial necessity, owned by businesses or individuals whose livelihoods depend on robust hauling capabilities. This clear demarcation of heavy-duty vehicles underscores the presence of a distinct working class and commercial sector whose automotive needs are starkly different from those of typical passenger vehicle owners.

In essence, while Canada’s classifications present some unique technical distinctions, the underlying socio-economic patterns they reveal are remarkably consistent with those in the United States. The availability and adoption of various vehicle classes—from the smallest subcompacts to the largest heavy-duty trucks—continue to delineate access to comfort, utility, perceived safety, and economic opportunity across different income brackets. This continental consistency highlights that the ‘car as a symbol of class division’ is a deeply embedded aspect of the North American automotive experience, influenced by regulatory frameworks designed for diverse purposes but with undeniable societal implications.

The labyrinthine world of automotive classifications, seemingly purely technical and bureaucratic, reveals itself to be a powerful, albeit indirect, mirror reflecting the intricate class divisions within American society and, by extension, North America. From the EPA’s volumetric metrics to NHTSA’s weight-based safety groups, FHWA’s functional categories, the Census Bureau’s truck focus, and IIHS’s crashworthiness scales, each system, in its own way, outlines who drives what, why they drive it, and what that choice implicitly says about their economic standing, aspirations, and even their safety on the road. These classifications are not just about regulating emissions or ensuring safety; they are silent architects of societal segmentation, delineating the contours of opportunity and necessity in the automotive landscape. As we navigate the complex roadways of American life, the vehicles we see and the systems that define them continue to narrate a story of division, utility, and aspiration, proving that even in the most technical of regulations, the echoes of class are undeniably present.