Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci, a name synonymous with genius, stands as a colossus of the High Renaissance, an Italian polymath whose profound impact spanned painting, draughtsmanship, engineering, science, and numerous other disciplines. Born in 1452, his life and work epitomized the humanist ideal, leaving an indelible mark on subsequent generations of artists and thinkers. While his artistic achievements, particularly a select few masterpieces, secured his initial fame, the breadth of his intellect and the depth of his empirical inquiries continue to fascinate and inspire.

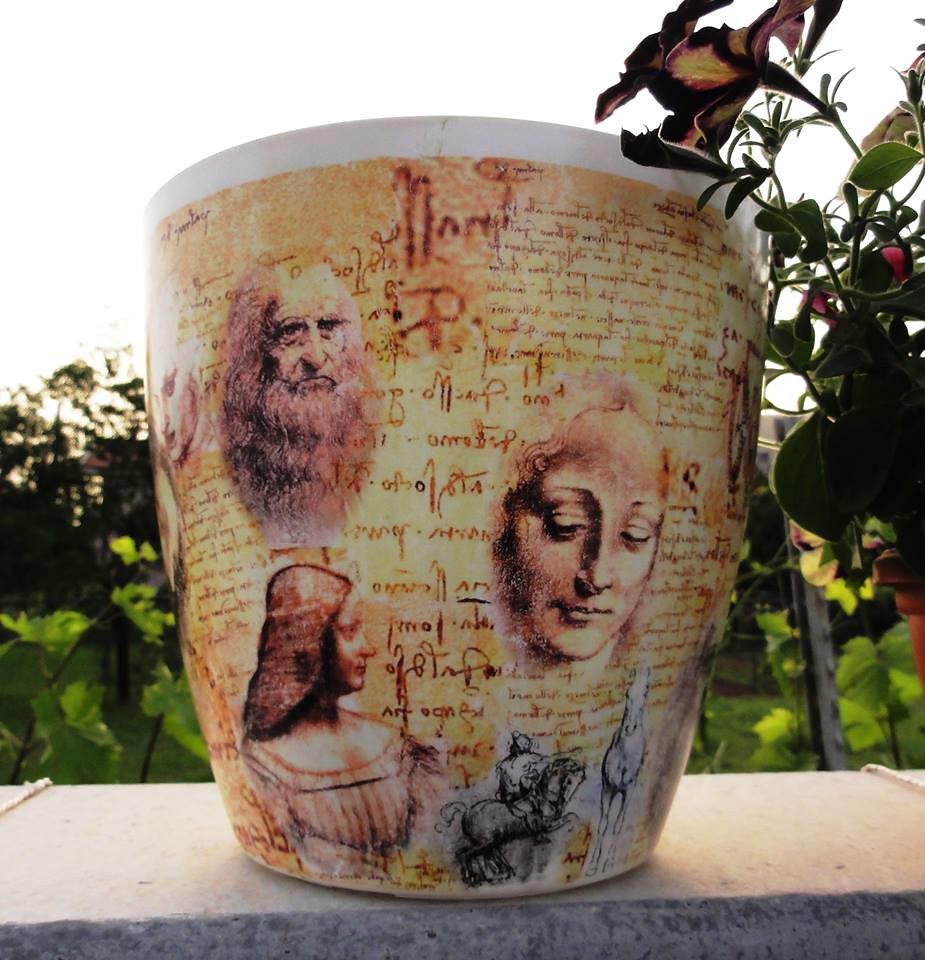

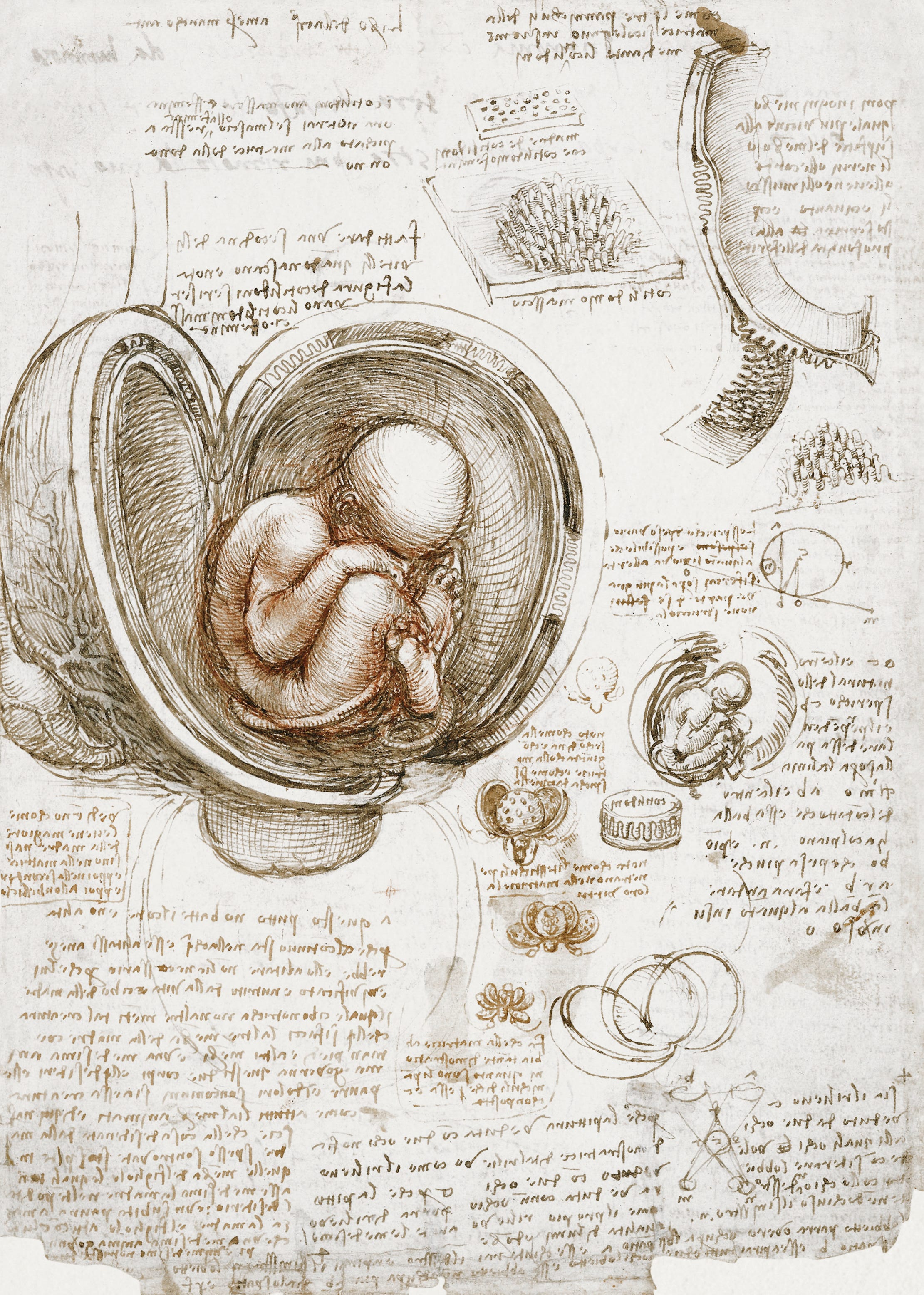

His legacy, far from being confined to the canvas, encompasses thousands of notebook pages filled with observations, theories, and designs that were centuries ahead of their time. From anatomical studies to visions of flying machines, Leonardo’s mind traversed every conceivable frontier of knowledge. This comprehensive exploration delves into the foundational periods of his extraordinary life, charting his evolution from a curious youth in a Tuscan village to a revered master under the patronage of powerful Italian city-states.

We embark on a detailed journey through the early chapters of Leonardo’s saga, examining the pivotal experiences and influences that shaped his singular vision. From the circumstances of his birth and an unconventional education to the rigorous training in Andrea del Verrocchio’s Florentine workshop, each stage reveals a developing intellect destined to redefine the boundaries of human achievement. The ensuing years saw him navigate significant commissions, cultivate influential relationships, and begin to articulate the revolutionary artistic and scientific principles that would characterize his entire career.

1. **A Polymath’s Genesis: Birth and Early Education (1452-1472)**Leonardo da Vinci, properly identified as Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci, indicating his father’s name and birthplace rather than a family surname, entered the world on April 15, 1452. His birth occurred in, or near, the Tuscan hill town of Vinci, approximately 20 miles from Florence. Born out of wedlock to a successful Florentine legal notary, Piero da Vinci, and a lower-class woman named Caterina di Meo Lippi, his origins were somewhat unconventional for the era.

While the exact location of his birth remains a subject of some debate, traditional accounts suggest Anchiano, a country hamlet offering privacy for an illegitimate birth, though a house in Florence belonging to his father is also a possibility. The year following his birth, both of Leonardo’s parents married separately, with Caterina eventually marrying a local artisan. Leonardo would later acquire 16 half-siblings, significantly younger than himself, with whom he maintained very little contact.

Despite his father’s lineage of notaries, Leonardo received only a basic and informal education in reading, writing, and mathematics in the vernacular. It is thought that his burgeoning artistic talents were recognized early, leading his family to direct their focus towards nurturing these abilities. This informal schooling, rather than a classical one, arguably contributed to his empirical, observational approach to learning and creation.

Little factual information is known about Leonardo’s childhood, with much of it being shrouded in myth, partly due to Giorgio Vasari’s frequently apocryphal biography. Records do indicate that by 1457, he resided in the household of his paternal grandfather, Antonio da Vinci, though he may have spent earlier years under his mother’s care. His earliest recorded memory, found in the Codex Atlanticus, describes a kite coming to his cradle and opening his mouth with its tail, an anecdote still debated as memory or fantasy.

2. **The Crucible of Creativity: Verrocchio’s Workshop (Mid-1460s – 1472)**In the mid-1460s, a pivotal moment arrived when Leonardo’s family relocated to Florence, a city then serving as the vibrant intellectual and cultural heart of Christian Humanist thought. Around the age of 14, he began his artistic journey as a ‘garzone,’ or studio boy, in the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio, who was considered the foremost Florentine painter and sculptor of his time. This apprenticeship began around the period of the death of Donatello, Verrocchio’s own master.

By the age of 17, Leonardo had formally become an apprentice, a role he maintained for seven years, undergoing intensive theoretical and practical training. The workshop environment was rich with talent, housing or associating with other future luminaries such as Ghirlandaio, Perugino, Botticelli, and Lorenzo di Credi. This exposure provided Leonardo with a broad education beyond pure art, encompassing drafting, chemistry, metallurgy, metal working, plaster casting, leather working, mechanics, and woodwork, alongside the artistic skills of drawing, painting, sculpting, and modeling.

Leonardo’s time in Verrocchio’s studio placed him at the nexus of the Florentine Renaissance, alongside contemporaries who would also achieve significant renown. He was undoubtedly influenced by the works of older artists like Masaccio, whose frescoes embodied realism and emotion, and Ghiberti, whose “Gates of Paradise” showcased complex figure compositions and detailed architectural backgrounds. The scientific study of perspective by Piero della Francesca and Leon Battista Alberti’s treatise “De pictura” also had a profound effect on the young artist’s observations and artworks.

A significant collaboration during this period was “The Baptism of Christ” (c. 1472–1475), a work largely attributed to Verrocchio, where Leonardo contributed. Vasari recounts that Leonardo painted the young angel holding Jesus’s robe with such exceptional skill that it purportedly led Verrocchio to lay down his brush and never paint again, though this latter claim is likely apocryphal. The application of the newly emerging technique of oil paint to areas such as the landscape and Jesus’s figure strongly suggests Leonardo’s hand. He may also have modeled for Verrocchio’s “David” and “Tobias and the Angel.”

One captivating anecdote from Vasari’s account details a youthful Leonardo’s response to a peasant’s request for a painted buckler shield. Inspired by the story of Medusa, Leonardo created a terrifying monster spitting fire, a work so unsettling that his father, Ser Piero, bought a different shield for the peasant. Leonardo’s creation was subsequently sold to a Florentine art dealer for 100 ducats, who then resold it to the Duke of Milan, illustrating the extraordinary impact of his early artistic prowess.

3. **Emergence as a Master: First Florentine Period (1472-c. 1482)**By 1472, at the age of 20, Leonardo had achieved the status of a master within the Guild of Saint Luke, the esteemed guild for artists and doctors of medicine. Despite this professional independence, and even after his father established him in his own workshop, Leonardo’s deep attachment to Verrocchio led him to continue collaborating and living with his former master. This period marked his formal entry into the professional art world, poised to take on significant commissions.

His earliest known dated work from this time is a pen-and-ink drawing of the Arno valley from 1473, a testament to his keen observational skills and burgeoning landscape artistry. It was also during this period that Vasari credits the young Leonardo with suggesting the audacious idea of making the Arno river a navigable channel between Florence and Pisa, foreshadowing his later extensive forays into civil engineering.

In January 1478, Leonardo received his first independent commission: an altarpiece for the Chapel of Saint Bernard in Florence’s Palazzo della Signoria. This commission unequivocally signaled his artistic autonomy from Verrocchio’s studio. Later, in March 1481, the monks of San Donato in Scopeto commissioned “The Adoration of the Magi.” However, neither of these initial, significant commissions were ultimately completed, as Leonardo soon turned his ambitions towards Milan.

Around 1480, an anonymous early biographer, Anonimo Gaddiano, suggests Leonardo was residing with the Medici family, frequently working in the garden of the Piazza San Marco, a hub for a Neoplatonic academy of artists, poets, and philosophers organized by the Medici. Through this connection, Leonardo encountered prominent Humanist philosophers such as Marsiglio Ficino, Cristoforo Landino, and John Argyropoulos, further enriching his intellectual landscape.

This network proved crucial; in 1482, Lorenzo de’ Medici dispatched Leonardo as an ambassador to Ludovico il Moro, who ruled Milan. Leonardo brought with him a silver string instrument, either a lute or lyre, crafted in the shape of a horse’s head, demonstrating his diverse talents beyond painting and engineering. This diplomatic mission ultimately opened the door to his influential First Milanese period.

4. **Milanese Patronage: The Court of Ludovico Sforza (c. 1482-1499)**Leonardo’s move to Milan in 1482 marked the beginning of a highly productive 17-year period under the patronage of Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan. His initial letter to Sforza was a masterful self-promotion, cataloging a diverse array of skills in engineering and weapon design, only mentioning his painting abilities towards the end. This strategic introduction highlighted his polymathic capabilities, perfectly aligning with the ambitions of a powerful Renaissance ruler seeking innovation.

During this time, he received two monumental artistic commissions: “Virgin of the Rocks” for the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception and “The Last Supper” for the refectory of the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie. These works would become cornerstones of Western art, showcasing his evolving techniques and profound understanding of human emotion and composition. He also undertook a brief journey to Hungary in 1485 on Sforza’s behalf, where he was commissioned by King Matthias Corvinus to paint a Madonna.

Beyond painting, Leonardo’s expertise was frequently sought for engineering and architectural projects. In 1490, he served as a consultant for the construction of the cathedral of Pavia, alongside Francesco di Giorgio Martini. His notebooks from this period began to fill with detailed studies and designs, encompassing everything from military fortifications to festive pageants, demonstrating the practical application of his boundless curiosity.

His role at Sforza’s court was comprehensive, involving the preparation of elaborate floats and pageants for special occasions, which undoubtedly honed his skills in design and mechanics. The period also saw him contribute to architectural competitions, notably a drawing and a wooden model for the cupola of Milan Cathedral, further solidifying his reputation as a visionary designer.

5. **Engineering Visionary: Unbuilt Innovations and the Gran Cavallo**Leonardo da Vinci’s tenure in Milan under Ludovico Sforza also saw the flowering of his incredible technological ingenuity, an aspect of his genius often overshadowed by his painting, yet equally revolutionary. He conceptualized an astonishing array of machines and devices that would not see practical realization for centuries. These included designs for flying machines, an early prototype of an armored fighting vehicle, sophisticated concentrated solar power systems, and even an early form of an adding machine capable of ratios, alongside the concept of the double hull for ships.

The context notes that “Relatively few of his designs were constructed or were even feasible during his lifetime, as the modern scientific approaches to metallurgy and engineering were only in their infancy during the Renaissance.” This highlights the visionary nature of his ideas, which often outstripped the material and technological capabilities of his era. While his grander designs remained on paper, some smaller inventions, such as an automated bobbin winder and a machine for testing the tensile strength of wire, silently entered manufacturing, showcasing his practical acumen.

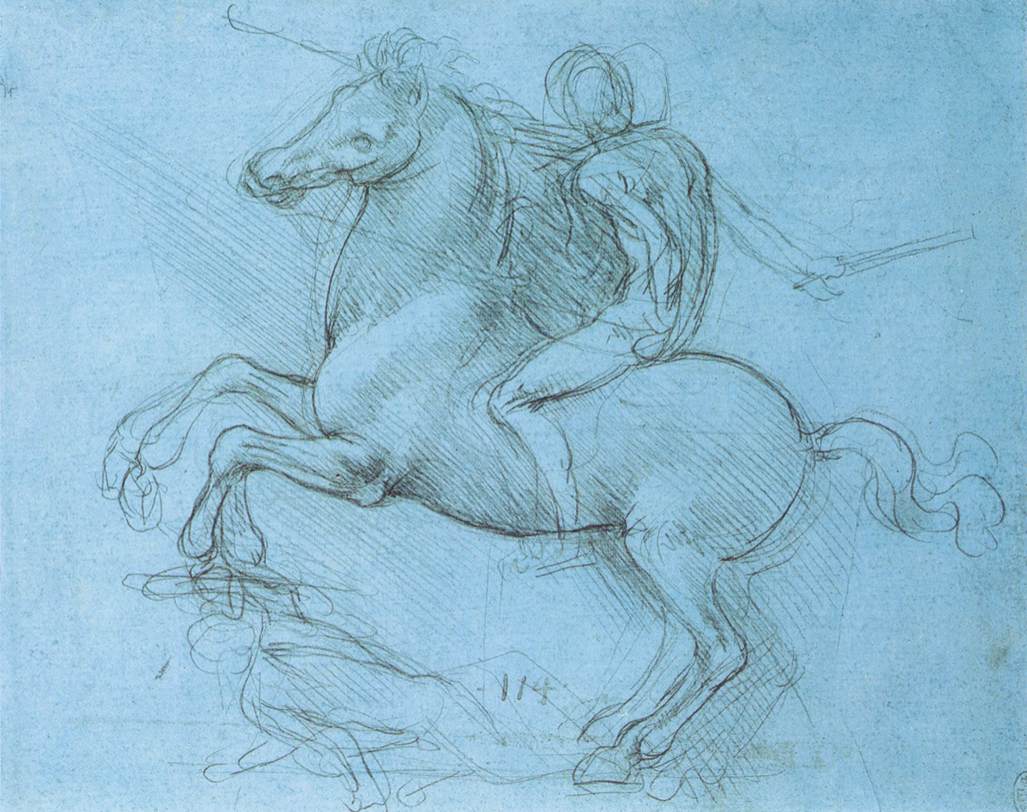

Perhaps the most ambitious engineering and artistic endeavor of this period was the “Gran Cavallo,” a colossal equestrian monument dedicated to Ludovico’s predecessor, Francesco Sforza. This project was envisioned to surpass in scale the existing large equestrian statues of the Renaissance, such as Donatello’s Gattamelata and Verrocchio’s Bartolomeo Colleoni. Leonardo poured considerable effort into this, completing a full-scale model for the horse and meticulously planning its casting.

The sheer ambition of the “Gran Cavallo” underscored Leonardo’s prowess as both a sculptor and an engineer capable of monumental undertakings. However, the exigencies of war intervened. In November 1494, the metal earmarked for the statue was tragically diverted by Ludovico to be used for cannons, needed to defend Milan from the advancing forces of Charles VIII of France. This decision brought the magnificent project to an abrupt halt, leaving one of Leonardo’s grandest visions unfulfilled.

6. **Artistic Triumphs and Challenges in Milan: The Last Supper and Sala delle Asse**Amidst his engineering pursuits, Leonardo’s artistic contributions during his First Milanese period reached an apex with “The Last Supper,” commissioned for the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie. This masterpiece depicts the dramatic moment when Jesus announces to his disciples, “one of you will betray me,” capturing the ensuing consternation and individual reactions with unparalleled psychological depth and realism. The painting is widely acclaimed as a “masterpiece of design and characterisation.”

Leonardo’s artistic process for “The Last Supper” was famously unconventional, reflecting his deep engagement with the subject. The writer Matteo Bandello observed his unique working habits, noting that some days Leonardo would paint from dawn till dusk without pause, while on other occasions, he would not touch his brush for three or four days at a time. This erratic pace, driven by intense periods of contemplation and execution, was perplexing to the convent’s prior, who “hounded him” until Leonardo appealed to Ludovico Sforza to intervene.

A particular challenge Leonardo faced was adequately depicting the faces of Christ and the traitor Judas. Vasari recounts that Leonardo, troubled by this artistic dilemma, candidly informed the Duke that he might be compelled to use the bothersome prior as his model for Judas, a testament to his dry wit and the pressures he endured. This anecdote offers a glimpse into the human element of his creative process and the social dynamics of his time.

Despite its immediate acclaim as a masterpiece, “The Last Supper” suffered a rapid deterioration. Leonardo, instead of employing the reliable fresco technique, experimented with tempera over a ground primarily composed of gesso. This innovative but ultimately flawed method left the surface vulnerable to mold and flaking, leading to its description by one viewer within a century as “completely ruined.” Nevertheless, its powerful composition and characterization ensured its status as one of the most reproduced works of art globally.

Towards the end of this fruitful Milanese period, around 1498, Leonardo also executed a remarkable trompe-l’œil decoration in the Sala delle Asse within the Castello Sforzesco for the Duke of Milan. This project transformed the great hall into an illusionistic pergola, where the interwoven limbs of sixteen mulberry trees created an intricate canopy of leaves and knots on the ceiling, showcasing his versatility and innovative use of perspective and natural forms.”

7. **Second Florentine Period: The Mona Lisa and the Battle of Anghiari (1500-1508)**Following the overthrow of Ludovico Sforza by French forces in 1500, Leonardo da Vinci embarked on a new chapter, first seeking refuge in Venice, where his skills were temporarily engaged in devising military defenses against potential naval attacks. Accompanied by his devoted assistant Salaì and the distinguished mathematician Luca Pacioli, his journey eventually led him back to the familiar intellectual and artistic hub of Florence in the same year. There, he and his household found hospitality with the Servite monks at the monastery of Santissima Annunziata, an arrangement that provided him with a much-needed workshop and a renewed creative impetus.

It was within this Florentine setting that Leonardo produced the revered cartoon of ‘The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and Saint John the Baptist.’ This particular work garnered widespread admiration, drawing crowds of “men and women, young and old” who flocked to witness its beauty “as if they were going to a solemn festival,” as noted by Vasari. This period also saw him briefly enter the service of Cesare Borgia in Cesena in 1502, acting as a military architect and engineer. During this time, Leonardo traveled extensively with his patron, creating meticulously detailed maps, including a town plan of Imola and a map of the Chiana Valley, demonstrating his strategic and cartographic prowess. He also conceptualized ambitious civil engineering projects, such as a dam to ensure a consistent water supply for Florence’s canal system.

By early 1503, Leonardo had returned to Florence, officially rejoining the Guild of Saint Luke in October of that year. This return marked the inception of what would become arguably his most iconic work: the portrait of Lisa del Giocondo, famously known as the ‘Mona Lisa.’ He would continue to refine this enigmatic painting into his twilight years, crafting a masterpiece renowned for its elusive smile, a quality often attributed to his innovative sfumato technique, or ‘Leonardo’s smoke,’ which subtly blurs contours and blends tones. The painting’s pristine preservation and the indistinguishable brushstrokes further contribute to its legendary status.

Another significant commission of this Florentine era was ‘The Battle of Anghiari,’ a monumental mural intended for the Salone dei Cinquecento in the Palazzo Vecchio. This commission placed Leonardo in direct artistic competition with Michelangelo, who was tasked with designing its companion piece, ‘The Battle of Cascina.’ Leonardo’s design depicted a dynamic and intense struggle for a standard, featuring four men on raging warhorses, a powerful composition that unfortunately deteriorated rapidly due to his experimental painting techniques and is now primarily known through a copy by Rubens.

8. **Second Milanese Period: New Projects and Renewed Scientific Inquiry (1508-1513)**By 1508, Leonardo da Vinci had once again established himself in Milan, residing in his own house in Porta Orientale within the parish of Santa Babila. This second period in Milan, though shorter than his initial residency, was characterized by continued artistic exploration and a renewed dedication to his scientific interests, reflecting his relentless curiosity and multidisciplinary genius.

During this time, Leonardo engaged with plans for another ambitious equestrian monument, this one dedicated to Gian Giacomo Trivulzio. These designs, building upon his earlier experiences with the ‘Gran Cavallo,’ showcased his continued mastery of monumental sculpture and engineering. However, like its predecessor, this project was ultimately thwarted by the political instability of the era, as an invasion by a confederation of Swiss, Spanish, and Venetian forces drove the French from Milan, bringing the commission to an abrupt halt.

Despite the political upheavals, Leonardo chose to remain in Milan for several months in 1513, finding a measure of quiet and continued opportunity for his intellectual pursuits at the Medici’s Vaprio d’Adda villa. This period allowed him the freedom to delve deeper into his scientific inquiries, a passion that often took precedence over specific artistic commissions. His notebooks from this time undoubtedly continued to fill with observations, sketches, and theories across his diverse fields of interest.

9. **Roman Interlude: Papal Patronage and Scientific Pursuits (1513-1516)**In March 1513, a significant shift in patronage occurred with Lorenzo de’ Medici’s son, Giovanni, assuming the papacy as Leo X. This event prompted Leonardo’s move to Rome in September of that year, where he was warmly received by the Pope’s brother, Giuliano de’ Medici. For approximately three years, from September 1513 to 1516, Leonardo resided in the Belvedere Courtyard within the Apostolic Palace, an environment bustling with artistic giants like Michelangelo and Raphael, yet one where Leonardo’s unique approach sometimes met with complications.

While in Rome, Leonardo received a monthly allowance of 33 ducats, affording him some stability. Vasari amusingly recounts an incident where Leonardo decorated a lizard with scales dipped in quicksilver, reflecting his playful curiosity and unconventional pursuits even amidst the solemnity of the Vatican. He was offered a painting commission by the Pope, but it was unfortunately cancelled when Leonardo, ever the innovator, embarked on developing a new type of varnish, a deviation that evidently did not align with papal expectations.

It was during this Roman period that Leonardo experienced an illness, possibly the first of several strokes that would eventually lead to his death. Despite these health challenges, his intellectual drive remained undiminished. He engaged in botanical studies within the Vatican Gardens, demonstrating his keen interest in the natural world. Furthermore, he was commissioned to devise plans for the Pope’s ambitious project to drain the Pontine Marshes, a testament to his continued reputation as a civil engineer.

His scientific explorations extended to detailed anatomical dissections, producing notes intended for a treatise on vocal cords. In an attempt to regain the Pope’s favor, he presented these findings to an official, though regrettably, this effort proved unsuccessful. This period in Rome, while offering new avenues for his diverse talents, also highlighted the challenges he faced in aligning his visionary, experimental methods with traditional patronage expectations.

10. **Final Years in France: Royal Patronage and Philosophical Reflections (1516-1519)**The political landscape shifted dramatically in October 1515 when King Francis I of France recaptured Milan. A testament to Leonardo’s international renown, he received a personal invitation from the young French monarch through his ambassador, Antonio Maria Pallavicini. The King eagerly awaited Leonardo’s arrival, promising him a warm reception at court, a testament to the high regard in which his genius was held.

Leonardo accepted the invitation, entering Francis I’s service later that year and relocating to the charming manor house of Clos Lucé, conveniently situated near the royal residence at the Château d’Amboise. Here, he spent his last three years, enjoying the patronage and admiration of the King, who frequently visited him. During this time, Leonardo drafted extensive plans for an immense castle town that Francis I envisioned constructing at Romorantin, showcasing his enduring architectural and urban planning prowess.

His inventive spirit also continued to entertain the French court, notably through the creation of a mechanical lion. This remarkable automaton, during a royal pageant, walked towards the King and, upon being struck by a wand, revealed a cluster of lilies from its chest, a symbolic gesture of homage to the French monarchy. These grand, festive creations demonstrated his unique blend of artistry, engineering, and theatrical flair.

Throughout these final years, Leonardo was steadfastly accompanied by his cherished friend and apprentice, Francesco Melzi, who would become his principal heir. Supported by a generous pension totaling 10,000 scudi, Leonardo enjoyed a period of relative comfort and intellectual freedom. It was during this time that Melzi captured a tender portrait of his master, one of the very few known from Leonardo’s lifetime, alongside other sketches that depicted an elderly Leonardo, notably with his right arm wrapped, confirming an account from October 1517 that his right hand was paralytic. This physical challenge may explain why certain works, such as the ‘Mona Lisa,’ remained unfinished, though he continued to work to some capacity until his final illness.

11. **The End of a Genius: Death and Last Will (1519)**Leonardo da Vinci, the incomparable polymath, passed away at Clos Lucé on May 2, 1519, at the age of 67, with a stroke being the likely cause of his demise. King Francis I, who had cultivated a deep personal friendship with the master, was reported to be profoundly affected by his death. Vasari, in his biography, recounts a poignant scene where Leonardo, on his deathbed, expressed repentance for “failing to practice his art as he should have done” and sought the Holy Sacrament from a priest. Vasari also vividly, if perhaps apocryphally, describes the King holding Leonardo’s head in his arms during his final moments, a testament to the immense respect and affection he commanded.

In accordance with his carefully laid will, Leonardo’s earthly remains were interred on August 12, 1519, in the Collegiate Church of Saint Florentin at the Château d’Amboise. His final wishes meticulously distributed his possessions and acknowledged those who had been close to him. Francesco Melzi, his loyal student and companion, was designated as the principal heir and executor, receiving a significant inheritance that included money, Leonardo’s treasured paintings, his tools, his extensive library, and personal effects, thereby safeguarding his intellectual and artistic legacy.

His other long-time pupil and companion, Salaì, whose presence in Leonardo’s household spanned three decades, along with his faithful servant Baptista de Vilanis, each received half of Leonardo’s vineyards, a token of his enduring gratitude. His surviving brothers were granted land, and even his serving woman was remembered with a fur-lined cloak, highlighting the personal consideration with which he managed his estate. The passing of such a monumental figure sent ripples across Europe.

Indeed, some two decades after Leonardo’s death, the renowned goldsmith and sculptor Benvenuto Cellini reported that Francis I, reflecting on the great master, proclaimed, “There had never been another man born in the world who knew as much as Leonardo, not so much about painting, sculpture and architecture, as that he was a very great philosopher.” This profound statement encapsulates the extraordinary breadth and depth of Leonardo’s genius, acknowledged by one of the most powerful rulers of his time.

12. **Unveiling the Man: Leonardo’s Personal Life and Intimate Relationships**Despite the thousands of pages of notebooks and manuscripts Leonardo da Vinci left behind, which offer unparalleled insight into his intellect, they reveal surprisingly little about his personal life. This reticence has only fueled centuries of curiosity and speculation about the man behind the genius, a fascination that began during his lifetime, particularly concerning his “great physical beauty” and “infinite grace,” as described by Vasari.

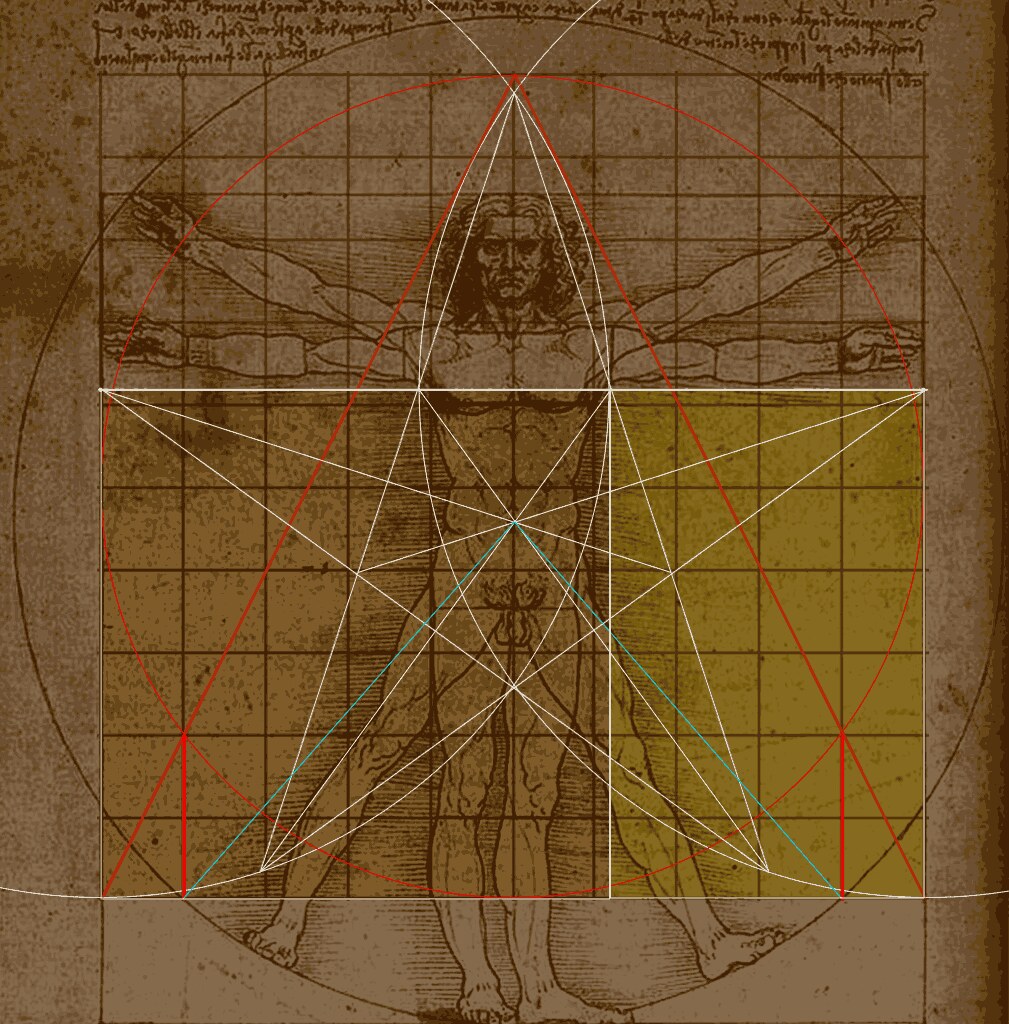

One striking aspect of his personality was his profound love for animals, often cited as a reason for his likely vegetarianism. Vasari notably recounted Leonardo’s habit of purchasing caged birds merely to release them, a compassionate gesture that speaks volumes about his character. His circle of friends included notable figures such as the mathematician Luca Pacioli, with whom he collaborated on the influential book ‘Divina proportione’ in the 1490s, demonstrating his intellectual camaraderie.

While Leonardo maintained friendships with women, such as Cecilia Gallerani and the Este sisters, Beatrice and Isabella, there is little evidence of close romantic relationships. His private life, particularly his uality, has been a perennial subject of analysis and debate. This discussion gained significant traction in the 19th and 20th centuries, famously explored by Sigmund Freud in his ‘Leonardo da Vinci, A Memory of His Childhood,’ and further elucidated by modern biographers like Walter Isaacson, who explicitly posited intimate, homosexual relations with his pupils.

Indeed, court records from 1476 show Leonardo, then twenty-four, and three other young men were charged with sodomy in an incident involving a known male prostitute. Though the charges were dismissed due to insufficient evidence, and some speculate that the Medici family’s influence played a role given a relative of one of the accused, this event has significantly shaped discussions about his presumed homouality and its subtle, yet pervasive, influence on his art. The androgyny and veiled eroticism seen in works like ‘Saint John the Baptist’ and ‘Bacchus,’ alongside explicitly erotic drawings, are frequently cited in this context.

Among his most intimate relationships were those with his pupils Salaì and Francesco Melzi. Melzi, in a letter informing Leonardo’s brothers of his death, described Leonardo’s feelings for his pupils as “both loving and passionate,” underscoring the deep emotional bonds within his household. Salaì, or ‘Il Salaino’ (‘The Little Unclean One’), entered Leonardo’s service in 1490 and, despite a long list of misdemeanors detailing him as “a thief, a liar, stubborn, and a glutton,” was treated with remarkable indulgence by Leonardo, remaining in his care for three decades. While Salaì produced paintings under his own name, his artistic merit is generally considered lesser than other pupils like Marco d’Oggiono or Boltraffio.

Remarkably, at the time of his death in 1524, Salaì owned a painting referred to as ‘Joconda’ in a posthumous inventory of his belongings, valued at an exceptionally high 505 lire for a small panel portrait. This detail provides a tantalizing, if indirect, link to the most famous painting in the world and highlights the complex, enduring personal connections that defined Leonardo’s life beyond his public artistic and scientific achievements.

Through these later periods, Leonardo da Vinci consistently defied categorization, moving fluidly between artistic creation, scientific inquiry, and engineering innovation. His life, marked by patronage from dukes, popes, and kings, was an unending quest for knowledge and expression. From the mysterious allure of the Mona Lisa to the grand designs of unbuilt machines, his later years cemented his legacy as a singular figure whose impact on art, science, and the very concept of human potential continues to inspire wonder and rigorous study, affirming his indelible place in the annals of history.