There’s an undeniable magic to literature, a timeless whisper that transcends generations, cultures, and technologies. It’s the art form that dares us to look closer, to feel deeper, and to question everything. From the profound introspection of a lyric poem to the sweeping scope of an epic novel, words have always been humanity’s most potent tool for expressing the inexpressible, shaping our collective consciousness, and mirroring our souls.

Yet, in our hyper-connected, fast-paced modern world, the very definition and appreciation of literature seem to be in constant flux. We find ourselves at a fascinating juncture, where the foundational pillars of literary art stand firm against a backdrop of seismic cultural and technological shifts. The traditional literary landscape, once defined by a shared canon and public intellectuals, now appears increasingly fragmented, diverse, and exhilaratingly, sometimes dauntingly, expansive.

This article embarks on an in-depth exploration of this dynamic terrain. We will journey through the very essence of what constitutes literature, distinguish between its various forms and merits, and then dive into the rich tapestry of American literary history – from its glorious past to its complex, often challenging, present. We’ll examine how technology both threatens and invigorates the written word, setting the stage for a compelling conversation about the future of an art form that, despite all odds, continues to redefine itself.

1. **Defining the Art of Literature: Beyond Mere Words**

At its heart, literature is a form of human expression, a carefully crafted arrangement of words that resonates with artistic merit. But what truly elevates writing to the esteemed rank of literature? It’s a question critics have grappled with for centuries, distinguishing the ephemeral from the enduring, the informative from the artful. While technical, scholarly, or journalistic writings are often excluded from this category, certain forms are universally recognized as belonging to literature as an art, provided they possess that elusive quality of artistic merit.

This merit isn’t always something actively pursued by the writer; sometimes, it emerges almost by accident. A scientific exposition, for example, might possess immense literary value, while a poem, despite its form, might have none at all if it fails to connect on a deeper, aesthetic level. This paradoxical nature underscores the elusive beauty of literature, where intent doesn’t always dictate outcome, and genuine artistry can blossom in unexpected places.

The spectrum of literary forms is vast and vibrant, each offering a unique lens through which to view the human experience. The lyric poem, often considered the purest and most intense literary expression, stands at one end, followed by elegiac, epic, dramatic, narrative, and expository verse. Literary criticism, in its quest to understand the aesthetic problems of literature, often bases its analyses on poetry, seeing it as the simplest and purest manifestation of these challenges. Yet, the reach of literature extends far beyond verse, encompassing great novels and even some historical works, essays, personal documents, philosophical texts, scientific observations, and oratorical masterpieces that transcend their original purposes to offer enduring satisfaction and truth.

2. **Literary Fiction Versus Genre Fiction: A Crucial Distinction**

Within the sprawling world of prose fiction, a significant distinction often arises between “literary fiction” and “genre fiction.” This separation isn’t always clear-cut, but it speaks to differing intentions and reader expectations. Literary fiction, as the context explains, frequently engages with “social commentary, political criticism, or reflection on the human condition.” Its pace can be slower, allowing the narrative “to dawdle, to linger on stray beauties even at the risk of losing its way,” as Terrence Rafferty notes.

This contrasts sharply with genre fiction—such as science fiction, fantasy, thrillers, or Westerns—where plot is often the central driving force. Saricks describes literary fiction as “elegantly written, lyrical, and … layered,” suggesting a deeper emphasis on style and complexity. It’s often seen as “all serious prose fiction outside the market genres,” emphasizing its focus on realistic human character and broader societal themes rather than specific commercial categories.

James Gunn further illuminates this divide by distinguishing between commercial and literary mainstreams. Commercial success, paradoxically, can sometimes lead to accusations that an author has “sold out,” implying a departure from the literary mainstream. The literary mainstream in the United States, according to Gunn, is largely shaped by an academic-literary community – professors, high-powered critics, and writers who take these circles seriously – and is significantly framed by classic works of European authors like Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, and Henry James, reflecting a particular intellectual tradition and valuing “art” over sheer popularity.

3. **The Enduring Power of Classic Literature: Western Canons and Global Heritage**

Classic literature forms the bedrock of our cultural heritage, comprising works in any discipline that have been accepted as exemplary or noteworthy across generations. These are the books that, as Robert M. Hutchins declared in his 1952 preface to the Great Books of the Western World, have “endured and that the common voice of mankind called the finest creations, in writing, of the Western mind.” They are considered essential for an educated person, forming a “canon” that shapes intellectual discourse and understanding.

In English literary studies, the terms “classic book” and “Western canon” are intrinsically linked, representing curated lists of essential texts often published in collections or prescribed as reading lists by academic institutions. These canons serve as cultural touchstones, transmitting values, ideas, and narrative traditions through time. However, the concept of a classic is not exclusive to the West. The Classic Chinese Novels, for instance, are celebrated for their immense impact on Chinese culture and literature, demonstrating a global appreciation for enduring literary masterpieces.

Ultimately, literary fiction, including these classics, often finds itself categorized as “high culture,” in contrast to “popular culture” or “mass culture.” Matthew Arnold, in his 1869 work “Culture and Anarchy,” defined “culture” as “the disinterested endeavour after man’s perfection” pursued through effort “to know the best that has been said and thought in the world.” This definition positions classics and philosophical works as forces for moral and political good, suggesting their profound role in shaping society’s ideals and fostering intellectual growth, extending their influence far beyond mere entertainment.

4. **Recognizing Literary Merit: The Prestige of Awards and the Price of Opinion**

The pursuit and recognition of literary merit culminate annually in prestigious awards that spotlight outstanding authors and works. Since 1901, the Nobel Prize in Literature has been a beacon, honoring writers from any country who have produced “the most outstanding work in an idealistic direction” over their entire body of work. While individual pieces might be cited, the award acknowledges a writer’s comprehensive contribution, affirming their lasting impact on the literary world and their ability to elevate humanity through words.

Similarly, the International Booker Prize and its predecessor, the Booker Prize, stand as significant British awards celebrating exceptional literary fiction. Judges, typically drawn from leading literary critics, writers, academics, and public figures, face the daunting task of selecting a “best book” from a vast pool of talent. These awards not only confer immense prestige but also shape public perception and reader interest, often propelling lesser-known works into the global spotlight.

However, the very process of judging and declaring a “best book” by a small group of literary insiders is not without controversy. Author Amit Chaudhuri critiques this, stating: “The idea that a ‘book of the year’ can be assessed annually by a bunch of people – judges who have to read almost a book a day – is absurd, as is the idea that this is any way of honouring a writer.” This highlights the subjective nature of literary value and the ongoing debate about how best to celebrate and define literary excellence in a constantly evolving cultural landscape.

5. **American Literature’s Golden Age: Shaping a Nation’s Soul**

There was a transformative era when American literature not only mirrored the nation’s spirit but actively sculpted it, becoming an indispensable part of the national conversation. The 19th century witnessed a determined effort by American writers to forge a voice distinct from European influences. Figures like Washington Irving and James Fenimore Cooper gained international recognition, but it was Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, and Walt Whitman who truly carved out a uniquely American literary identity, delving into themes of individualism, morality, and the relentless search for identity within a burgeoning nation.

Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass” was a profound declaration of independence for American poetry, a raw, expansive celebration of the self and the collective. Melville’s “Moby-Dick” plunged into existential depths as vast and formidable as the sea itself, grappling with questions of obsession and human limits. Hawthorne’s “The Scarlet Letter” unflinchingly exposed the moral hypocrisies embedded in Puritan America. Together, these titans established a literary tradition that was bold, questioning, and undeniably American, reflecting both the nation’s promise and its profound contradictions.

The 20th century then erupted as American literature’s undisputed “true golden age.” This period saw an explosion of audacious, experimental, and unyielding voices. F. Scott Fitzgerald masterfully captured the disillusionment of the Jazz Age in “The Great Gatsby,” while Ernest Hemingway’s stark, minimalist prose laid a new stylistic blueprint for generations of writers. William Faulkner redefined the American South with his intricate narratives, and later, Toni Morrison confronted America’s racial traumas head-on with unforgettable works like “Beloved,” ensuring that literature remained at the forefront of societal dialogue and introspection. During this era, writers were not just storytellers; they were public intellectuals, their insights sought on politics, culture, and the very state of the human soul.

6. **A Fragmented Landscape: American Literature in the 21st Century**

Fast-forward to the 21st century, and the vibrant, singular literary scene of yesteryear has morphed into something vastly different: a fragmented, niche-driven landscape. Today’s literature often struggles to command attention amidst the cacophony of competing entertainment forms. Netflix binges, addictive TikTok videos, and immersive video games now vie for the leisure hours once dedicated to the quiet contemplation of a novel. For many, literature simply cannot compete with the immediate gratification offered by these newer media, leading to a perception that its influence has diminished.

This fragmentation is echoed within the publishing industry itself. While established giants like Penguin Random House and HarperCollins continue their dominance, there has been an explosion of independent presses, hybrid publishers, and accessible self-publishing platforms. This democratization has undeniably opened doors for marginalized voices, allowing stories previously ignored by traditional gatekeepers to find an audience. The result is a richer, more varied American literature, with writers like Viet Thanh Nguyen, Jesmyn Ward, Colson Whitehead, and Tommy Orange crafting works that delve into race, history, and identity with extraordinary depth and nuance.

Yet, this proliferation of voices presents a complex challenge. The sheer volume of books means that literary culture feels scattered, lacking the focal points of the past. Instead of a handful of major authors shaping national discourse, we now encounter countless “micro-literatures” operating in distinct silos. One community might champion autofiction, another experimental narratives, while a third devours young adult dystopias. The very notion of a shared national literary canon, a common touchstone for collective conversation, is increasingly becoming a nostalgic relic, reflecting a broader societal shift towards personalized consumption and segmented cultural experiences.

7. **Technology’s Double-Edged Sword: The Digital Age and the Written Word**

The relationship between technology and literature has always been complex, often perceived as a struggle between old and new. In the 20th century, radio and television were seen as existential threats to the novel’s dominance. Today, it is the internet, and particularly social media platforms, that prompt critics to sound alarm bells, raising concerns about the future of deep, sustained engagement with the written word. Platforms like TikTok and Instagram have fundamentally altered how books are marketed and consumed, with phenomena like BookTok becoming powerful engines for sales, especially in young adult and fantasy genres. While some argue this is simply a modern way to encourage reading, others worry it reduces literature to viral trends and aesthetically pleasing “shelfies,” potentially superficializing the literary experience.

Beneath the surface of this new marketing lies a deeper concern: the erosion of attention spans. Studies consistently indicate a decline in sustained reading habits. A 2021 Pew Research Center survey revealed that approximately 23% of American adults reported not reading any books in the previous year, a figure that encompasses all types of books, not just literary fiction. Social media algorithms, designed for rapid dopamine hits and fleeting engagement, fundamentally clash with the deep, immersive concentration that serious literature demands, potentially rewiring our cognitive patterns away from complex narratives.

However, technology is far from an unalloyed antagonist. It wields a beneficial edge, too. E-books and audiobooks have dramatically enhanced literature’s accessibility, allowing more people to engage with stories in new and convenient formats. Furthermore, online writing communities have fostered a new generation of authors, many of whom honed their craft in fan-fiction forums before securing major publishing deals. Writers such as E.L. James (of “Fifty Shades of Grey” fame) and Andy Weir (known for “The Martian”) owe their remarkable careers directly to the expansive and democratizing opportunities presented by the digital age, proving that technology can indeed be a powerful ally in the ongoing evolution of literature.

8. **The Decline of the Public Intellectual: A Fading Voice**

One of the most profound shifts in the literary landscape, marking a stark contrast between American literature’s past and its present, is the noticeable diminishment of the public intellectual’s role. There was a time, not so long ago, when literary titans like James Baldwin, Susan Sontag, and Norman Mailer were not merely celebrated for their fiction but were household names whose insights were sought on everything from civil rights to foreign policy. Their essays and public debates actively shaped the national conversation, offering nuanced perspectives that resonated far beyond academic circles.

Today, the idea of a single novelist wielding such widespread cultural clout seems almost anachronistic. While contemporary figures like Ta-Nehisi Coates or Roxane Gay certainly command significant attention, their influence often stems as much from their compelling nonfiction and active social media presence as it does from their fiction. This evolution suggests a shift in how intellectuals engage with the public, moving from a singular, authoritative voice to a more distributed, multi-platform presence, reflecting the broader fragmentation of media consumption.

This decline isn’t an isolated phenomenon; it’s intricately linked to transformations within the media ecosystem itself. The long-form magazine essay, once a staple for deep intellectual discourse, has seen a contraction, while newspaper book sections have dwindled. In their place, we often find the immediacy and brevity of clickbait journalism, which struggles to accommodate the depth and complexity serious literary thinkers require. Furthermore, a more polarized political climate frequently expects authors to adopt clear, activist stances, sometimes inadvertently sacrificing the very literary nuance that defined earlier public intellectualism.

9. **The Education Crisis: Who’s Reading the Classics Now?**

The challenges confronting American literature extend deeply into the educational system, where a quiet crisis is unfolding regarding the engagement with classic works. For generations, high school and college syllabi were replete with canonical American texts—“The Catcher in the Rye,” “To Kill a Mockingbird,” “The Grapes of Wrath”—books that served as shared cultural touchstones and formative intellectual experiences. Yet, in many contemporary classrooms, these same works are increasingly debated, challenged, or even removed, sometimes due to concerns about their dated perspectives or perceived offensive content.

Compounding this curricular shift is a broader systemic devaluation of the humanities within education. Across universities and institutions, STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) consistently attract the lion’s share of funding and student enrollment, often at the expense of English departments. Many literature courses have been reduced in scope or, in some unfortunate instances, eliminated altogether, reflecting a societal prioritization of practical skills over the nuanced critical thinking fostered by literary study.

The ripple effects of this educational transformation extend far beyond campus grounds. If successive generations do not encounter and engage with serious literature during their formative years, the likelihood of them developing a lifelong habit of reading such works as adults significantly diminishes. When schools de-emphasize the teaching of how to grapple with complex narratives, it is hardly surprising that the broader literary marketplace begins to cater to simpler, more immediately digestible forms of storytelling, potentially eroding the intellectual foundation necessary for appreciating profound literary art.

10. **Mario Vargas Llosa: The Last Titan of the Latin American Boom**

The recent passing of Mario Vargas Llosa in Lima at the age of 89 marks a poignant moment, signifying the departure of the last representative of the golden generation that defined Latin American literature’s iconic ‘boom.’ A universal writer whose narrative genius emerged from the intricate tapestry of Peruvian reality, Vargas Llosa stood alongside luminaries like Gabriel García Márquez, Julio Cortázar, Carlos Fuentes, and Juan Rulfo. His departure is a loss not just for his family and friends, but for countless readers globally who found solace and profound insight in his multifaceted and fruitful life’s work.

Vargas Llosa’s literary prowess was evident in masterpieces that intricately described social realities, such as “The Time of the Hero” (La ciudad y los perros) and “The Feast of the Goat” (La fiesta del chivo). These works cemented his position as a literary giant, capable of dissecting complex human and societal dramas with unparalleled precision. Beyond his literary accolades, his unyielding liberal positions frequently sparked spirited debate and even hostility among intellectual circles, particularly those with leftist leanings, demonstrating his willingness to engage with the political and social currents of his time.

His insightful commentary on the Latin American spirit—”Latin Americans are dreamers by nature and we have trouble distinguishing between the real world and fiction. That is why we have such great musicians, poets, painters, and writers, and also such horrible and mediocre rulers”—underscored a deep understanding of his continent’s unique cultural psyche. Confirmed by his Nobel Prize in Literature in 2010 and his subsequent incorporation into the French Academy in 2023, Vargas Llosa’s universal appeal highlighted an intellectual and artistic legacy that transcended borders, proving that truly great literature knows no single nationality.

His prodigious literary career, launched in 1959 with the short story collection “The Bosses,” rapidly gained momentum with novels like “The Time of the Hero” (1963) and “The Green House” (1966), solidifying with “Conversation in the Cathedral” (1969). Even after receiving the Nobel, he continued to write prolifically, producing works such as “The Discreet Hero” and “Cold Times,” a reflection on 20th-century Guatemala’s turbulent history. Translated into 30 languages, his numerous awards—including the Cervantes Prize and the Prince of Asturias Award—are a testament to a writer who truly continued his craft until his very last days, leaving behind a monumental body of work that will continue to challenge and enchant readers for generations.

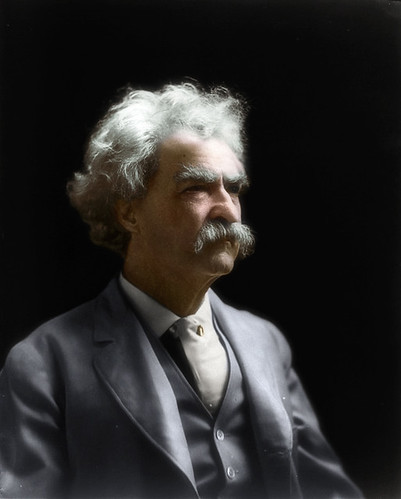

11. **Mark Twain: America’s Irreverent Conscience**

Born Samuel Langhorne Clemens in 1835 in a Missouri divided by slavery and the promise of progress, Mark Twain became America’s irreverent conscience. His formative years along the Mississippi River immersed him in the stark contradictions of American society, experiences that profoundly shaped his worldview. From riverboat pilot to newspaper writer, Twain honed a uniquely American voice, one steeped in sharp observation, biting wit, and an unparalleled knack for storytelling, preparing him to become arguably the nation’s most beloved — and most subtly provocative — literary figure.

Twain’s works transcended mere entertainment, functioning as incisive cultural critiques masterfully cloaked in humor. “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” (1885) remains a cornerstone of American literature, fiercely debated for its portrayal of race and its audacious questioning of societal norms. The odyssey of Huck and Jim down the Mississippi is far more than a simple boy’s adventure; it is a subversive odyssey into the very essence of freedom, morality, and the profound hypocrisy embedded within a society that espoused liberty while simultaneously upholding the institution of slavery. Other works, such as “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer” (1876), offered a quintessential glimpse into childhood mischief, while “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court” (1889) ingeniously satirized medieval superstition through the lens of modern ingenuity.

Twain’s impact on Western thought is as profound as it is enduring. He bequeathed to America its distinctive literary cadence—an inimitable blend of sarcasm, irony, and earnest social critique. His acerbic humor continues to reverberate through modern satire, influencing everything from late-night comedy to political cartoons. More significantly, Twain possessed the singular courage to confront uncomfortable truths with a wit so piercing that it continues to cut through the cacophony of contemporary discourse. His voice was not merely America’s conscience; it was a powerful declaration that humor could, and indeed should, serve as an indispensable instrument for societal change, a legacy that still teaches us the power of laughter in the face of absurdity.

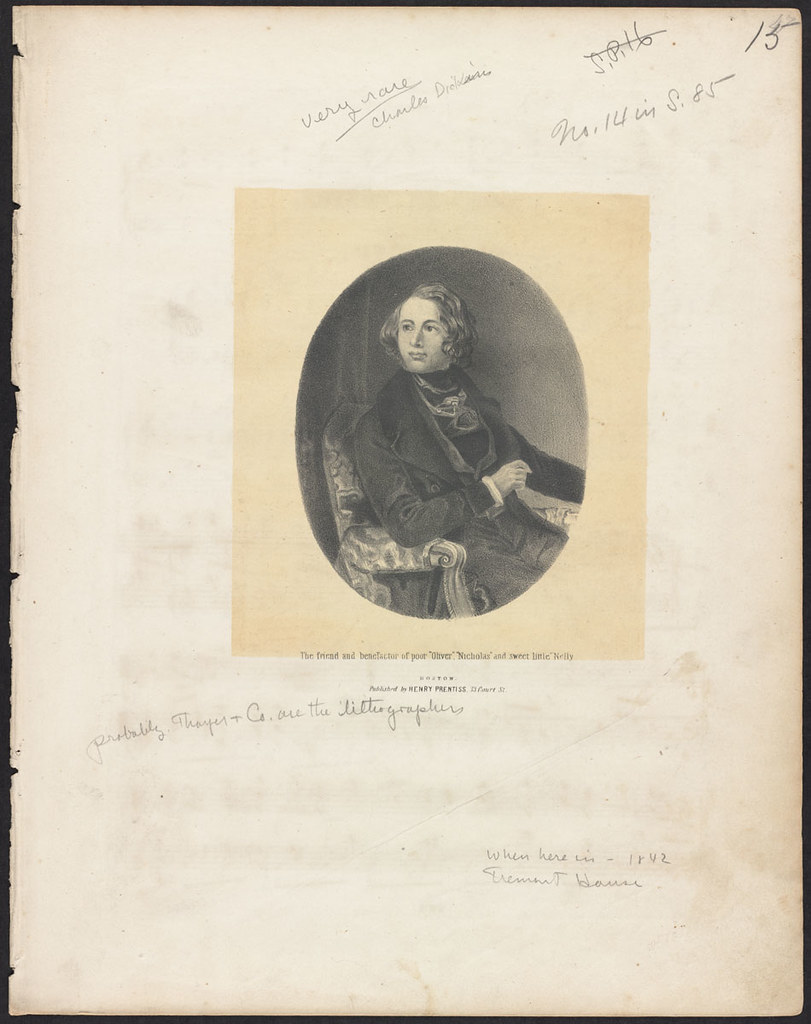

12. **Charles Dickens: The Conscience of the Industrial Age**

Charles Dickens, born in Portsmouth, England, in 1812, rose from a childhood scarred by adversity and shaped by an unyielding resilience. His father’s incarceration for debt cast a long shadow, compelling young Dickens into the harsh realities of factory work. This searing experience ignited a lifelong empathy for the plight of the poor and a fervent determination to challenge the ingrained injustices of his era. Dickens was more than a storyteller; he was a social reformer through prose, his novels not mere flights of fancy but urgent blueprints for a more compassionate and equitable society.

In seminal works like “Oliver Twist” (1837), Dickens unflinchingly laid bare the brutal truths of child labor, endemic poverty, and rampant crime within Victorian England. He amplified the voices of the voiceless, vividly depicting the barbarity of workhouses and orphanages, forcing his readers to confront the suffering often hidden in plain sight. “A Christmas Carol” (1843) transcended its festive veneer to become a scathing indictment of unchecked greed, serving as a powerful, enduring call for human kindness and collective responsibility. And in the sweeping narrative of “A Tale of Two Cities” (1859), Dickens expertly explored the chaotic genesis of revolution, arguing persuasively that profound systemic inequality inexorably leads to societal upheaval and violence.

Dickens’ colossal impact on Western ideology is immeasurable. His masterful storytelling humanized the struggles of the working class, compelling the affluent segments of society to confront the uncomfortable truth that their privilege often came at a staggering human cost. Today, his indelible influence persists in countless modern narratives focused on social justice and economic disparity, demonstrating the timeless relevance of his critiques. Dickens did not simply chronicle the Industrial Revolution; he held its often-cruel machinery to account. His enduring legacy lives on in every piece of social commentary that champions empathy, advocates for reform, and passionately strives for a more just world, a testament to the power of a pen wielded for profound societal good.

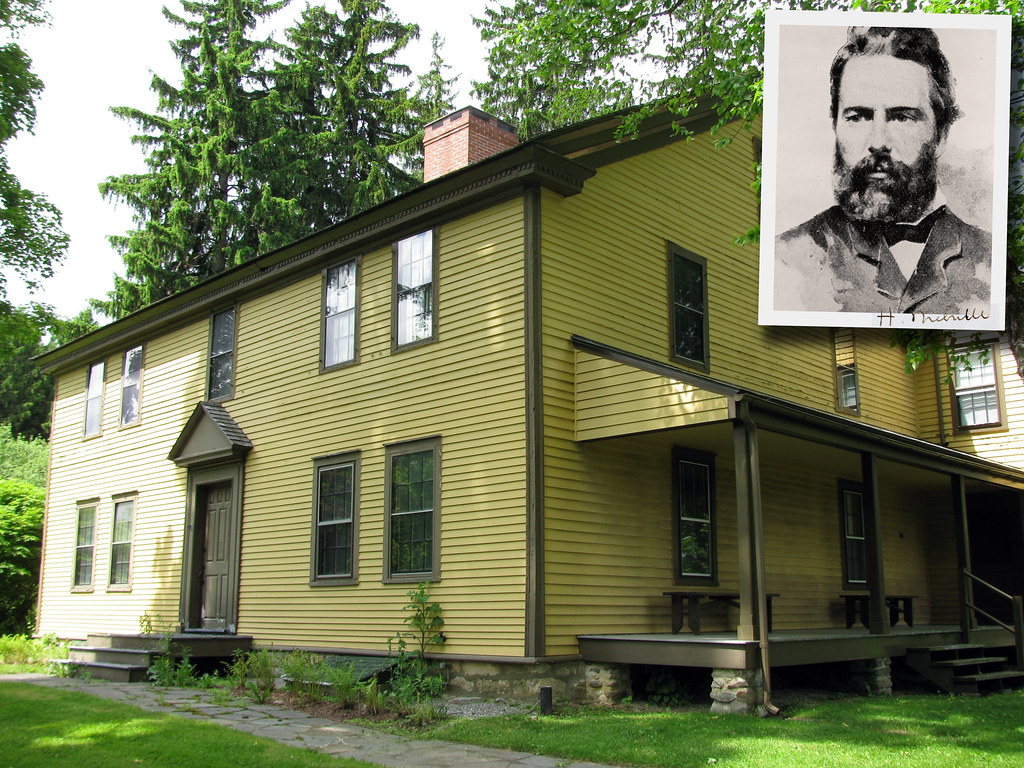

13. **Herman Melville: The Prophet of Obsession**

Herman Melville, born in New York in 1819, lived a life defined by adventure and profound hardship, experiences that would indelibly stamp his literary output. His early years as a sailor on whaling ships exposed him to the raw, often brutal realities of life at sea, a world of both immense beauty and terrifying indifference. While initially lauded for early works such as “Typee” (1846), his magnum opus, “Moby-Dick” (1851), was met with widespread critical indifference during his lifetime, consigning him to relative obscurity. It was only long after his death that Melville was finally recognized as one of America’s most towering literary minds, a prophet ahead of his time.

“Moby-Dick” transcends the simple confines of a seafaring adventure; it is an epic, multi-layered exploration of human obsession, the intoxicating allure of madness, and the relentless, often futile, struggle against an indifferent, unfathomable universe. Captain Ahab’s monomaniacal pursuit of the elusive white whale stands as a timeless metaphor for ambition unbridled by reason, a terrifying descent into self-destructive fixation. The novel’s dense symbolism and profound philosophical depths proved challenging for his contemporary readers, but its prescient examination of humanity’s darker, unyielding impulses now resonates as a powerful commentary on the inherent dangers of single-minded, all-consuming quests.

Beyond his epic, Melville also offered quieter yet equally impactful narratives, such as “Bartleby, the Scrivener” (1853). This enigmatic tale portrays passive resistance through its titular character, a scrivener who famously “prefers not to” engage with the demands of the world around him. This narrative, too, was far ahead of its time, exploring themes of alienation, existential detachment, and quiet rebellion against societal expectations.

Melville’s influence on modern thought, while often subtle, is profoundly pervasive. His masterful depiction of obsession as a self-annihilating force predates many modern psychological narratives, while his creation of complex, morally ambiguous characters foreshadows the conflicted protagonists prevalent in contemporary literature. Melville’s expansive vision of human ambition, portrayed as simultaneously noble and tragically damning, continues to challenge and provoke readers, serving as a powerful reminder that the relentless pursuit of greatness can, all too often, lead to an individual’s ruin. His works endure in the collective consciousness, perennial cautionary tales about the profound, sometimes devastating, cost of chasing unattainable ideals into the abyss.

14. **George Orwell: The Prophet of Paranoia**

Born Eric Arthur Blair in British-controlled India in 1903, George Orwell’s worldview was fundamentally shaped by his direct experiences with stark class disparity and the pervasive machinery of imperialism. Educated at the prestigious Eton College, he later served as a colonial officer in Burma, an experience that instilled in him a deep-seated disdain for oppression, authoritarianism, and the inherent abuses of unchecked power. Orwell’s writing was never merely literary; it was inherently political, meticulously crafted to expose the insidious mechanisms of control and to illuminate the grave perils posed by totalitarian regimes.

His allegorical novella, “Animal Farm” (1945), masterfully transformed political critique into a deceptively simple fable, vividly illustrating how revolutionary ideals, born of noble aspirations, can become tragically corrupted and twisted into new forms of tyranny. Its allegorical portrayal of the Russian Revolution served as an urgent, timeless warning against the dangers of totalitarianism, where the promise of liberation devolves into systematic oppression. “Nineteen Eighty-Four” (1949), Orwell’s most enduring and chilling work, created a dystopian world where relentless surveillance, pervasive censorship, and manipulative propaganda combine to utterly crush individuality and free thought.

The concepts famously introduced in “Nineteen Eighty-Four” — “Big Brother” and “doublethink” — have transcended the pages of the novel to become integral elements in our contemporary lexicon, frequently invoked in discussions about government overreach, media manipulation, and the erosion of personal freedoms. This pervasive influence proves that Orwell’s dark, meticulously constructed vision was not merely paranoid speculation, but rather an uncannily prescient anticipation of many anxieties that continue to plague modern society.

Orwell’s monumental legacy is firmly rooted in his fierce, unwavering commitment to truth and his profound belief in the individual’s moral duty to resist oppression, intellectual dishonesty, and manipulation. His ideas permeate Western thought on civil liberties, human rights, and the paramount importance of dissent in a free society. Every instance where we question governmental surveillance, challenge the insidious forces of censorship, or scrutinize the narratives presented by powerful institutions, we are, in essence, living out Orwell’s critical and cautionary lessons. His work stands as a relentless, urgent reminder that freedom is an incredibly fragile commodity that must be ceaselessly defended against those who would seek to rewrite reality for their own self-serving ends, a profound and necessary warning for every generation.

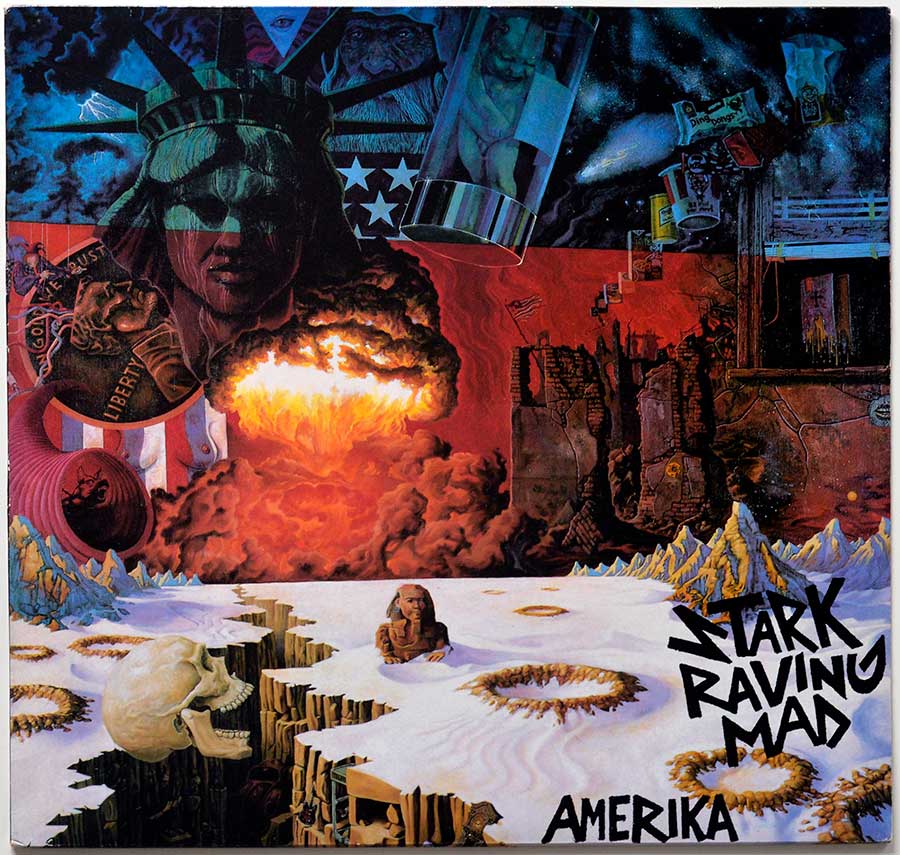

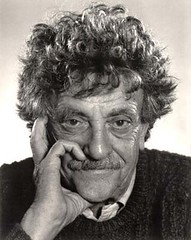

15. **Kurt Vonnegut: The Jester Who Saw It All**

Born in Indianapolis, Indiana, in 1922, Kurt Vonnegut’s life was a vibrant, often tragic, kaleidoscope of experiences that profoundly shaped his distinctive literary voice. As a young soldier during World War II, he was captured and survived the devastating firebombing of Dresden. This harrowing event left an indelible, haunting mark on his worldview, infusing his subsequent writing with a unique blend of dark humor, existential contemplation, and a wry, almost resigned sense of irony. Vonnegut’s stylistic approach was refreshingly unorthodox, blending elements of science fiction, biting satire, and philosophical inquiry, all delivered with an unmistakable, often heartbreaking, wit.

His most celebrated and enduring novel, “Slaughterhouse-Five” (1969), stands as a powerful testament to the futility and senselessness of war. The narrative ingeniously captures this theme through the fractured, non-linear timeline of its protagonist, Billy Pilgrim, a soldier who becomes “unstuck in time” after experiencing the horrors of Dresden. Vonnegut’s audacious ability to seamlessly weave stark realism with fantastical elements profoundly challenged traditional narrative forms, rendering his critique of war not only deeply personal but also universally resonant, forcing readers to confront the absurdity of human conflict through a uniquely fragmented lens.

Vonnegut was a master of the absurd, using his distinctive narrative style to comment on the inherent irrationality of the human condition and the often-comic futility of our endeavors. His works, beyond “Slaughterhouse-Five,” like “Cat’s Cradle” and “Breakfast of Champions,” explored themes of free will, technology’s impact, environmental degradation, and the search for meaning in a chaotic universe, always with a signature blend of cynicism and unexpected tenderness. He created a pantheon of memorable characters and introduced concepts like “so it goes” to process unimaginable tragedy, demonstrating that sometimes, laughter and fatalism are the only sane responses to an insane world.

Vonnegut’s influence on modern literature and thought is significant, particularly in his pioneering use of metafiction, dark humor, and an overtly conversational tone that broke down the barrier between author and reader. He empowered subsequent generations of writers to experiment with form and voice, to grapple with complex moral questions without resorting to simplistic answers, and to find the humanity in even the most dystopian settings. His legacy is that of a compassionate iconoclast, a jester who saw the deepest truths about humanity’s capacity for both creation and destruction, and then chose to tell us about it with a shrug and a profound, knowing wink, ensuring his voice remains a potent and comforting presence in an increasingly bewildering world.

So, is this truly the end of an era for American literature, a forgotten art fading into the digital ether? Perhaps. But eras, much like the human spirit they reflect, rarely conclude with a definitive, abrupt stop; they evolve, transform, and redefine themselves. The familiar model—where a select few towering authors held sway over the national literary conversation—is indeed receding into history. In its place, we are witnessing the exhilarating emergence of a literary world that is undeniably messier, far more diverse, and, frankly, infinitely more intriguing. The challenges are real and undeniable: the brutal economics of publishing persist, cultural attention spans continue to fragment, and the once-prominent role of the author as a singular public intellectual has undergone a significant diminishment. Yet, literature, in its essence, has always been a shape-shifter, an art form that thrives on reinvention and adapts to the currents of its time. American literature, in particular, has repeatedly proven its capacity for profound metamorphosis. The pressing question before us isn’t whether American literature is dying; rather, it is what vibrant new forms it is actively transforming into, and, crucially, who, in this exhilarating and complex new era, will ultimately decide what truly constitutes literary greatness.