The number four. It’s more than just a digit that follows three and precedes five; it’s a profound, omnipresent organizing principle woven deeply into the very fabric of our reality, from the cosmos to the smallest biological building blocks. Often overlooked in its unassuming position, four subtly dictates everything from the architecture of the universe to the fundamental laws governing matter, and even the abstract constructs of human thought and belief systems. This seemingly simple integer holds a weight of significance that belies its humble appearance.

In an era of relentless information, where attention spans are fleeting, pausing to truly appreciate the enduring influence of such a fundamental concept offers a rare and deeply satisfying intellectual journey. Its resonance extends far beyond the confines of arithmetic, shaping our understanding of space, time, and the very structures that define life itself. Prepare to delve into an exploration that reveals why the number four has echoed throughout history, culture, and science, solidifying its place as a truly foundational pillar of existence.

This journey will uncover the multifaceted nature of four, exposing its critical role in defining our world in ways both seen and unseen. We will traverse historical evolutions of its visual representation, plumb the depths of its mathematical properties, soar through its celestial manifestations, and scrutinize its biological imperatives, each revelation adding another layer to its compelling narrative of universal importance.

1. **The Enduring Shape of ‘Four’: Evolution of its Glyph

Our relationship with numbers is often visually mediated, and the journey of the glyph for four offers a fascinating glimpse into humanity’s pursuit of efficiency and clarity in representation. Initially, early civilizations, like the Brahmin Indians, would represent numbers one, two, and three with an equivalent number of lines. However, as the context reveals, “writing four lines proved tiresome,” a simple yet profound observation that spurred a millennia-long evolution in its visual form. This practical challenge led to an ingenious simplification, where the four lines were joined into a cross, a form strikingly similar to our modern plus sign.

This initial innovation, born out of a desire for less laborious transcription, set the stage for subsequent transformations. The Sunga and other Indian cultures further refined this, adding a horizontal line on top, while the Kshatrapa and Pallava civilizations prioritized aesthetic and perhaps ceremonial concerns over mere speed, evolving the numeral into more complex designs. The narrative of the glyph’s evolution speaks volumes about cultural priorities, shifting from pure utility to more intricate artistry.

The Arabs, known for their pragmatic contributions to mathematics and script, brought a renewed focus on efficiency. Their version of four retained the “early concept of the cross” but was crafted in “one stroke by connecting the ‘western’ end to the ‘northern’ end,” with the “eastern” end concluding in a curve. This ingenious single-stroke design exemplifies a culture valuing both recognition and rapid execution. Eventually, Europeans streamlined this further, dropping the ornamental finishing curve and gradually simplifying the numeral, culminating in the glyph we recognize today—a form that strikingly “ended up with a glyph very close to the original Brahmin cross,” bringing the journey full circle in an elegant testament to the enduring power of practical design.

2. **Four in Foundational Mathematics: From Basic Operations to Prime Factorization

At the very bedrock of mathematical understanding, the number four asserts its presence with an unyielding consistency, forming fundamental principles that underpin vast swathes of numerical theory. It stands as the “natural number that follows 3 and precedes 5,” a cardinal marker integral to counting and classification. Indeed, four is intricately linked to the very definition of arithmetic, being one of the “four elementary arithmetic operations in mathematics: addition (+), subtraction (−), multiplication (×), and division (÷),” a quartet of actions without which modern mathematics would be unimaginable.

Moving beyond basic operations, four quickly reveals its unique properties within the realm of number theory. It holds the distinction of being the “smallest composite number,” meaning it can be formed by multiplying two smaller positive integers, with its “proper divisors being 1 and 2.” This classification as a composite number, along with its status as a “highly composite number,” highlights its rich divisibility. Furthermore, it is the “second square number,” elegantly expressed as 2 × 2, showcasing its relationship to geometric squares and making it the “smallest squared prime (p²).”

Its numerical identity is further cemented by intriguing patterns, such as the compelling observation that “2 + 2 = 2 × 2 = 2² = 4.” This peculiar self-referential property extends into more advanced notation, where “2 ↑ ↑ 2 = 2 ↑ ↑ ↑ 2 = 4” in Knuth’s up-arrow notation, illustrating its consistency across various levels of mathematical abstraction. Four’s aliquot sum, which is the sum of its proper divisors, is 3, itself a prime number, leading to an aliquot sequence of four members (4,3,1,0), adding another layer to its fascinating numerical profile. As the “smallest composite number that is equal to the sum of its prime factors,” it also claims the title of the “smallest Smith number,” solidifying its singular position in the intricate tapestry of integers.

3. **Geometric Harmony: Quadrilaterals, Tetrahedrons, and the Base of Plane Mathematics

The indelible mark of the number four is profoundly evident in the foundational principles of geometry, shaping our understanding of both two-dimensional planes and three-dimensional solids. When we envision flat shapes, the “four-sided plane figure is a quadrilateral or quadrangle, sometimes also called a tetragon.” This fundamental shape serves as a cornerstone, encompassing a diverse family of figures such as rectangles, kites, rhombuses, and squares—each a ubiquitous presence in both natural and constructed environments. The geometric ubiquity of these forms underscores four’s essential role in defining spatial relationships and architectural integrity.

Extending into three dimensions, four continues its definitive influence, giving rise to the simplest and most fundamental polyhedral form: the tetrahedron. A “solid figure with four faces as well as four vertices is a tetrahedron,” holding the distinction of being “the smallest possible number of faces and vertices a polyhedron can have.” This elementary solid is not just minimal but also exquisitely balanced, with the “regular tetrahedron, also called a 3-simplex, is the simplest Platonic solid.” Its composition of “four regular triangles as faces that are themselves at dual positions with the vertices of another tetrahedron” reveals a profound symmetry and efficiency in its design.

Beyond individual shapes, the number four also emerges as a fundamental organizing principle for larger geometric systems. The context notes that “a circle divided by 4 makes right angles,” directly linking four to the concept of orthogonality and forming “the base number of plane (mathematics).” This deep connection extends to our very perception of the world, influencing concepts like “four cardinal directions” and “four seasons,” demonstrating how mathematical principles rooted in four permeate our understanding of natural cycles and spatial orientation, firmly establishing its role as a bedrock of geometric harmony.

4. **The Four-Color Theorem: A Mapmaker’s Conundrum Solved

Few mathematical puzzles have captivated the minds of scholars and laymen alike quite like the Four-Color Theorem, a proposition whose elegant simplicity belies the profound complexity of its proof. This theorem posits a seemingly straightforward concept: “a planar graph (or, equivalently, a flat map of two-dimensional regions such as countries) can be colored using four colors, so that adjacent vertices (or regions) are always different colors.” It’s a principle familiar to anyone who has ever tried to color a map, ensuring no two neighboring countries share the same hue.

The genius of the theorem lies not just in its statement, but in the surprising realization that “three colors are not, in general, sufficient to guarantee this.” This distinction elevates four from a mere arbitrary choice to a critical threshold, delineating the absolute minimum required to achieve this universal cartographic harmony. The implication is profound: four colors are not just enough; they are, for all practical purposes, precisely what’s needed to differentiate any adjacent regions on a flat surface without ambiguity.

The theorem’s elegance extends to its graphical representation, where “the largest planar complete graph has four vertices,” reinforcing the intrinsic connection between the number and this specific topological property. The Four-Color Theorem, through its intricate proof and fundamental statement, stands as a testament to the unexpected depth found within seemingly simple mathematical problems, showcasing how the number four plays an indispensable role in defining the limits and possibilities of graphical representation and spatial organization. It reminds us that even abstract mathematical principles have very tangible, real-world applications, from cartography to network design.

5. **Lagrange’s Four-Square Theorem: Deconstructing Integers

The intrinsic power of the number four extends deeply into the realm of number theory, where it unlocks profound insights into the very composition of integers. One of the most celebrated examples of this is Lagrange’s four-square theorem, a remarkable statement that asserts “every positive integer can be written as the sum of at most four squares.” This theorem, named after the brilliant mathematician Joseph-Louis Lagrange, offers a fundamental understanding of how numbers can be broken down into their squared components, revealing an underlying structure to the integer system.

The “at most four squares” clause is critical, highlighting the efficiency and sufficiency of this specific count. The context explicitly clarifies this necessity by pointing out that “three are not always sufficient; 7 for instance cannot be written as the sum of three squares.” This illustrative example underscores why four is not merely a convenient number, but a mathematically proven maximum that guarantees the representation of any positive integer through this specific operation. It’s a powerful demonstration of four’s role as an upper bound in this particular number-theoretic pursuit.

Lagrange’s theorem is more than just an abstract curiosity; it’s a cornerstone of additive number theory, a field dedicated to understanding how numbers can be expressed as sums of other numbers. Its implications resonate across various branches of mathematics, solidifying the number four’s status as a critical conceptual tool for deconstructing and understanding the fundamental properties of integers. The elegance of its statement and the rigor of its proof exemplify the deep and often surprising connections that numbers hold, showcasing four as a pivotal player in the grand architecture of numerical relationships.

6. **Celestial Quads: The Number Four in Our Solar System and Beyond

From the grand sweep of planetary orbits to the intricate dance of stellar phenomena, the number four repeatedly surfaces as a significant organizational principle within the vast expanse of astronomy. Our own cosmic neighborhood, the Solar System, provides compelling evidence of this fourfold arrangement. We are home to “four terrestrial (or rocky) planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars,” which stand in distinct contrast to the gas giants. This initial quartet of inner worlds forms a crucial category in planetary science, each with its own unique characteristics but bound by their rocky composition.

Further out, the pattern of four re-emerges with equal prominence, defining another major class of celestial bodies: the “four giant gas planets in the Solar system: Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune.” These colossal worlds, entirely different in their gaseous makeup, complete the primary planetary census of our sun. The division of our Solar System’s major planets into these two distinct groups of four underscores a natural, perhaps even inherent, structuring principle that the number embodies. The context also notes that “the orbits of four planets in the solar system lie within that of the asteroid belt,” further hinting at this recurring numerical theme in cosmic architecture.

Beyond our immediate planetary family, the number four continues its astronomical appearance in more specialized contexts. For instance, the “Saros number of the solar eclipse series that began on May 6, 2731 B.C.E. and ended on June 13, 1451 B.C.E.” is four, a specific designation in the prediction of recurring eclipses. Similarly, “The Roman numeral IV (usually) stands for the fourth-discovered satellite of a planet or minor planet,” and “IV also stands for subgiant in the Yerkes spectral classification scheme,” demonstrating how four acts as a descriptor and classifier in humanity’s ongoing quest to map and understand the universe.

7. **The Biological Blueprint of Four: From DNA to Human Anatomy

The intricate machinery of life itself appears to be deeply influenced, if not fundamentally orchestrated, by the number four, manifesting its presence from the microscopic world of genetics to the macroscopic structures of animal and human anatomy. At the very core of heredity, “four is the number of the most common nucleotides in DNA and RNA, and therefore also the number of the most common bases in these nucleic acids: Adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine (uracil in RNA).” This elemental quartet forms the genetic alphabet, encoding the vast complexity of all living organisms and serving as the fundamental blueprint for life.

Moving up the scale of biological organization, the anatomical world of many creatures reveals an undeniable four-part symmetry or structure. For instance, “many chordates have four feet, legs or leglike appendages (Tetrapods),” a classification that encompasses a vast array of vertebrate life, including amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. This ubiquitous tetrapodal design highlights an evolutionary efficiency and success tied directly to this numerical arrangement. Even within our own species, specific anatomical details reflect this pattern: “Under normal conditions of maturity, each human has four canines, four incisors, and four wisdom teeth,” demonstrating a precise, balanced dental structure.

Furthermore, critical physiological systems within mammals, including humans, exhibit this fourfold organization. The “mammalian heart consists of four chambers,” a highly efficient design that separates oxygenated and deoxygenated blood, crucial for complex metabolic processes. Beyond the internal, external structures also comply, as “many mammals (Carnivora, Ungulata) use four fingers for movement,” showcasing adaptability in locomotion. Even the broad classification of human biology, such as “four human blood groups (A, B, O, AB),” underscores how this number acts as a fundamental classifier and organizer within the astonishing diversity and complexity of the living world.

The journey into the profound impact of the number four continues, as we shift our gaze from its foundational elements to its pervasive reach across diverse fields, further cementing its status as an unparalleled architectural principle of existence. From the unseen forces governing matter to the intricate designs of technology and the spiritual contours of human belief, four persistently emerges as a silent yet powerful orchestrator, shaping our world in ways both tangible and abstract.

Read more about: The Enduring Significance of Four: An In-depth Analysis of Its Pervasive Influence Across Disciplines

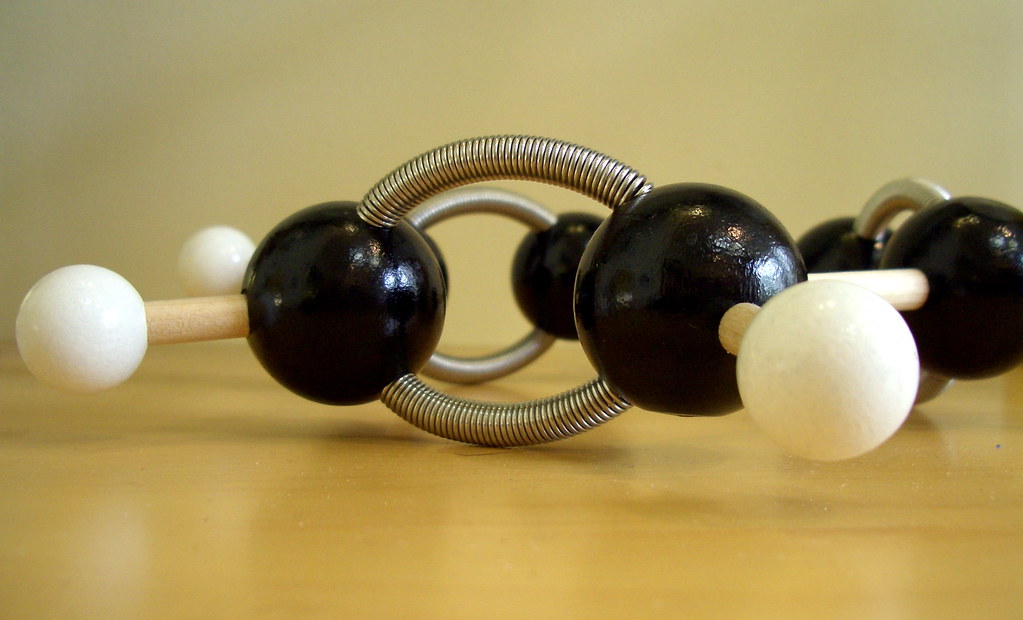

8. **Chemical Foundations: Carbon’s Valence and the States of Matter

In the realm of chemistry, the number four stands as a fundamental cornerstone, most notably embodied by carbon, the very bedrock of life on Earth. This miraculous element boasts a normal valence of four, a property that grants it an unparalleled ability to form stable, complex molecular structures. It is this tetramerous bonding capacity that makes carbon the quintessential building block for organic compounds, enabling the vast and intricate diversity of life we see around us.

Beyond carbon’s central role, four’s chemical significance extends to silicon, another element whose compounds, much like carbon’s, exhibit a valence of four. Silicon’s ubiquity is not to be understated; its compounds constitute the majority of Earth’s crust, forming the silicate minerals that define much of our planet’s geology. This shared tetrahedral bonding characteristic between carbon and silicon underscores four’s profound influence on both biological and geological structures, illustrating its deep imprint on the material world.

Further cementing four’s chemical presence, it is the atomic number of beryllium, a light and strong alkaline earth metal with crucial applications. Moreover, the universe organizes matter itself into four basic states: solid, liquid, gas, and plasma. These distinct phases, each defined by unique energy levels and molecular arrangements, represent fundamental transformations of matter, creating the diverse physical conditions that characterize our cosmos. From the atomic architecture of life to the grand states of existence, four is an intrinsic part of chemistry’s foundational narrative.

.jpg)

9. **The Fabric of Reality: Four Dimensions in Physics

The universe, in its most profound descriptions, often reveals a four-dimensional character, a concept elegantly captured within the grand theories of physics. Minkowski space, a foundational framework for special relativity, posits a reality composed of three dimensions of space intertwined with one dimension of time. This four-dimensional continuum, known as spacetime, is not merely a mathematical construct but a deeply insightful representation of how events unfold in our physical universe.

Both special relativity and general relativity, Albert Einstein’s revolutionary theories, treat nature as inherently four-dimensional. By fusing three-dimensional space with time, they unveil a unified fabric where matter and energy interact, where gravity bends the very geometry of existence. This conception of spacetime reshaped our understanding of cosmology, gravity, and the interconnectedness of all physical phenomena, proving that four is a non-negotiable component of how we perceive and measure reality.

Beyond the macroscopic scales of spacetime, the number four continues to appear in the subatomic world and fundamental forces that govern it. An alpha particle, which is essentially a helium nucleus, robustly consists of four hadrons, embodying a compact and stable configuration of subatomic matter. More profoundly, all interactions in the cosmos are governed by precisely four fundamental forces: electromagnetism, gravity, the weak nuclear force, and the strong nuclear force. These four forces dictate everything from the attraction of planets to the decay of radioactive elements, collectively orchestrating the fabric of the universe itself, demonstrating four’s undeniable role in shaping cosmic law.

10. **Technological Tandems: How Four Shapes Our Modern Tools and Systems

In the ever-evolving landscape of technology and everyday design, the number four frequently emerges as a practical and efficient principle, subtly dictating the form and function of countless innovations. Consider the common pieces of furniture we encounter daily; tables and chairs, the very staples of domestic and professional environments, are typically built upon four sturdy legs. This simple yet effective design principle ensures stability and balance, making these items universally reliable and functional.

Furthermore, the ubiquitous rectangle, a four-sided plane figure, serves as a cornerstone in construction and manufacturing due to its inherently effective form and capability for close adjacency. This geometric efficiency makes rectangular shapes ideal for everything from houses and rooms to bricks, sheets of paper, computer screens, and film frames. The rational and modular nature of the rectangle, anchored by its four angles and sides, underpins much of our built environment, showcasing four’s influence on structural integrity and spatial organization.

Four also plays a crucial role in information and visual processing. The four-color process, famously known as CMYK (Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Key/Black), is the foundational method for commercial printing, allowing for the reproduction of a full spectrum of colors from just these four pigments. In the digital realm, four is the number of bits in a nibble, a fundamental unit of digital information equivalent to half a byte, illustrating its presence even in the microscopic architecture of computing. Even in rich text format specifications, language code 4 is designated for the Chinese language, with regional variants being congruent to 4 mod 256, demonstrating four’s systematic application in global communication standards. Its recurrence across these varied technological applications underscores its indispensable value in shaping modern tools and systems.

11. **The Wheels of Progress: Four in Transport and Automotive Innovation

The world of transport, a crucial arena for human progress, owes much of its efficiency and stability to the enduring principle of the number four. From the earliest carriages to the most sophisticated modern vehicles, the four-wheeled configuration has remained a prevailing design. Most motor vehicles, particularly cars and light commercial vehicles, inherently feature four road wheels, a design choice that provides optimal balance, traction, and maneuverability, foundational elements for safe and reliable travel.

This fundamental design choice is not merely a matter of convention but a testament to its practical superiority, allowing vehicles to distribute weight evenly, absorb shocks, and maintain directional stability across diverse terrains. The four points of contact with the ground offer a robust platform for engineering excellence, enabling the complex mechanics of acceleration, braking, and steering that define modern automotive performance.

The significance of four in automotive innovation is perhaps most strikingly exemplified by Audi’s iconic “Quattro” trademark. Derived from the Italian word for four, “Quattro” signifies the brand’s pioneering four-wheel drive (4WD) technologies. Introduced in 1980 with the original Audi Quattro coupé, this system revolutionized off-road and high-performance driving by delivering power to all four wheels, enhancing grip and control under challenging conditions. Audi’s dedication to this four-wheeled philosophy, even extending to its privately held subsidiary company, quattro GmbH, underscores how this numerical concept has not only shaped individual vehicles but also driven an entire segment of automotive engineering, firmly placing four at the heart of transport’s ongoing evolution.

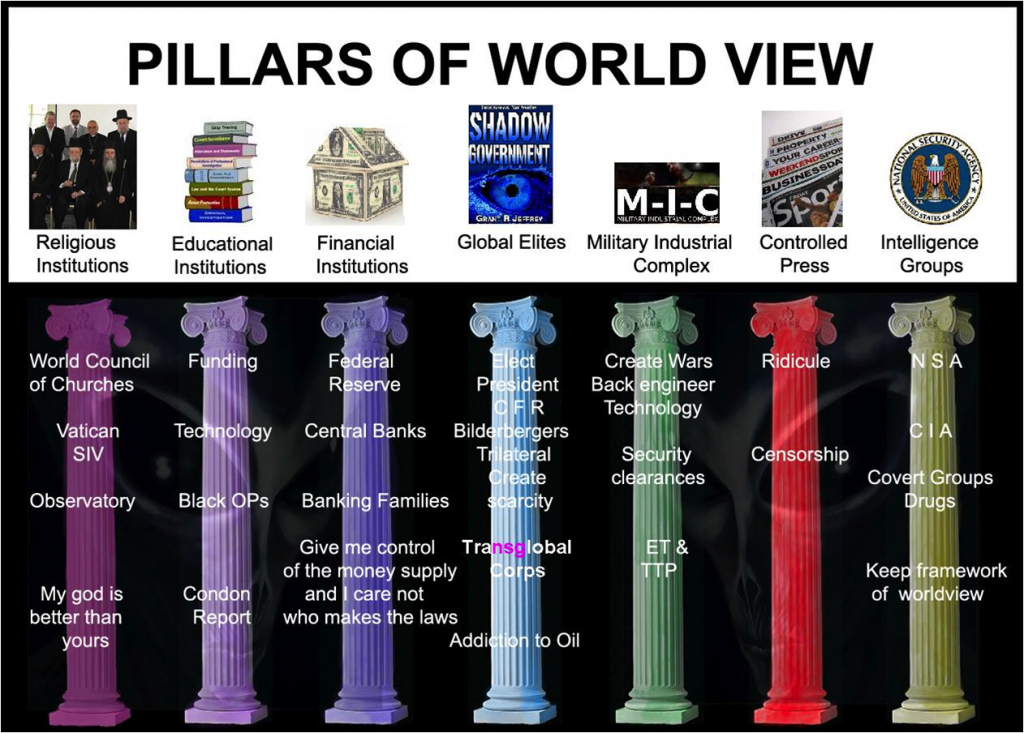

12. **Sacred Structures: The Pervasive Role of Four in World Religions

Across diverse cultures and millennia, the number four has resonated deeply within spiritual and philosophical traditions, imbued with symbolic meanings of wholeness, universality, and solidity. From prehistoric times, its association with the cross’s four points rendered it an “outstanding symbol of wholeness and universality,” drawing all elements into itself. This fundamental symbolism underpins its pervasive presence in global religions, signifying comprehensive order and divine structure.

In Judaism, four is a profoundly sacred number, interwoven into the very fabric of its foundational texts and rituals. The Tetragrammaton, YHVH, the unutterable name of God, comprises four letters, representing the divine essence. The Garden of Eden is depicted with four rivers, symbolizing paradise and life-giving abundance. Furthermore, Judaism’s key observances are rich with fourfold elements: the four Matriarchs (Sarah, Rebeccah, Leah, Rachel), the Four Species taken on Sukkot, the Four Cups of Wine, Four Questions, Four Sons, and Four Expressions of Redemption during Passover, each reflecting layers of spiritual meaning and historical narrative.

This fourfold sacredness extends to other major faiths, underscoring its universal appeal. In Islam, four Archangels (Jibraeel, Mikaeel, Izraeel, Israfil) stand as celestial intermediaries. Christianity is founded upon the narratives of the four canonical Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John), offering diverse perspectives on the life of Christ, and the ominous Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse ride in the Book of Revelation, signifying ultimate judgment. Even in Buddhism, the Four Noble Truths form the very core of its teachings, providing the path to enlightenment. For the Zia, an indigenous tribe of New Mexico, four is their sacred number, reflecting the cardinal directions and the stages of life. This consistent appearance across disparate belief systems highlights four’s potent capacity to encapsulate divine order and profound spiritual truths.

13. **Philosophical Pillars: Fourfold Understanding in Logic and Thought

Beyond its mystical and religious associations, the number four has long served as a fundamental organizing principle in the rigorous landscapes of logic and philosophical thought, providing frameworks for understanding the world and structuring rational inquiry. Its ancient symbolic connection to solidity and wholeness makes it a natural fit for building robust intellectual systems, embodying comprehensive understanding.

In the realm of formal logic, the Square of Opposition, in both its Aristotelian and Boolean versions, consists of four distinct forms: A (“All S is R”), I (“Some S is R”), E (“No S is R”), and O (“Some S is not R”). These four propositions define the fundamental relationships between universal and particular, affirmative and negative statements, forming a bedrock for deductive reasoning. Similarly, Aristotle, the towering figure of ancient philosophy, posited that there are fundamentally four causes in nature: the efficient cause, the matter, the end, and the form, offering a comprehensive framework for explaining existence and change.

Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant, in his critical philosophy, expounded a table of judgments involving four three-way alternatives regarding Quantity, Quality, Relation, and Modality. Building upon this, he derived a table of four categories, each with three subcategories, which he considered the fundamental concepts of the understanding. Later, Arthur Schopenhauer, a profound figure in German philosophy, dedicated his doctoral thesis to “On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason,” dissecting the various forms of causality that govern knowledge and reality. Even the pragmatic C.S. Peirce, despite his usual trichotomies, discussed four basic methods for seeking to settle questions and arrive at firm beliefs: the method of tenacity, the method of authority, the a priori method, and the method of science. These profound philosophical engagements underscore four’s enduring role as a foundational tool for dissecting complexity and building coherent systems of thought.

14. **Harmonic Structures: The Number Four in Music and its Iconic Ensembles

In the vibrant and emotive world of music, the number four acts as a silent architect, providing fundamental structures that underpin countless compositions and performances. From the very bedrock of Western musical notation, common time is constructed of four beats, establishing a rhythmic pulse that guides melodies and harmonies. Classical music frequently adheres to this fourfold pattern, with symphonies and string quartets typically featuring four movements, creating a satisfying narrative arc of musical expression.

Beyond formal structures, the number four profoundly shapes musical ensembles. The string quartet, a quintessential chamber music group, comprises four instruments: two violins, a viola, and a cello, each contributing to a rich, interwoven texture. Similarly, instruments like the violin, viola, cello, double bass, cuatro, and ukulele universally feature four strings, a design choice that balances playability with a broad tonal range. The very concept of a “quartet” – a group of four musicians – embodies this numerical ideal, fostering a unique dynamic and blend that has captivated audiences for centuries.

Among the most iconic quartets to ever grace the stage, The Beatles, affectionately known as the “Fab Four” (John Lennon, Ringo Starr, George Harrison, and Paul McCartney), revolutionized popular music, demonstrating the immense power of a tight-knit four-piece band. Yet, another legendary quartet, one whose soulful harmonies defined an era, was The Four Tops. This incredible group, co-founded by Levi Stubbs, Renaldo “Obie” Benson, Lawrence Payton, and Abdul ‘Duke’ Fakir, became synonymous with the Motown sound, delivering timeless hits like “I Can’t Help Myself (Sugar Pie, Honey Bunch)” and the operatic masterpiece “Reach Out I’ll Be There.”

Their influence was monumental, sparking a friendly rivalry with The Temptations and earning fervent admiration from peers like Smokey Robinson and Stevie Wonder, who eloquently inducted them into The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Even The Beatles themselves were avid fans, with George Harrison captured in the Peter Jackson documentary *Get Back* urging his bandmates to incorporate The Four Tops’ chorus into their own new material. The Four Tops performed together for over four decades without a single personnel change, a remarkable testament to their bond and artistic integrity, selling more than 50 million records and shaping the landscape of soul music forever.

Tragically, as a testament to the inexorable march of time, the golden era that The Four Tops so vibrantly illuminated has seen its final light dim. With the recent passing of Abdul ‘Duke’ Fakir at 88, he became the last of the original lineup to depart, following Lawrence Payton, Renaldo “Obie” Benson, and lead vocalist Levi Stubbs. Though their physical presence may now be a cherished memory, their collective legacy, a timeless echo of unparalleled musical artistry and camaraderie, continues to resonate through generations. Fakir’s determination to carry on the group’s name with new vocalists underscored the enduring power of their music, ensuring that the harmonic structures they built, anchored in the essence of four, will continue to uplift and inspire.

A Lasting Echo

From the ancient patterns etched into our very numerical representations to the profound symmetries found in the cosmos, the subtle dictates of mathematics, and the intricate blueprints of biology, the number four has consistently revealed itself as an undeniable force. Its influence permeates the invisible realms of chemical bonds and the fundamental forces of physics, extends into the meticulously engineered systems of technology and transport, and profoundly shapes the spiritual narratives of global religions. It underpins the very pillars of philosophical thought and provides the rhythmic heartbeat and harmonic structures of our most cherished music, giving rise to iconic ensembles that resonate through time. The pervasive reach of four is not mere coincidence, but rather a compelling testament to its fundamental role in defining the order, beauty, and complexity of our existence. It is a number that truly echoes throughout everything, a constant, unwavering presence that invites us to look deeper, listen closer, and appreciate the elegant architecture of reality itself.