In a world that constantly seeks to identify, celebrate, and elevate those with extraordinary intellect, the concept of genius often conjures images of groundbreaking discoveries, artistic masterpieces, and paradigm-shifting innovations. We are captivated by the sheer power of minds that “surpasses expectations, sets new standards for the future, establishes better methods of operation, or remains outside the capabilities of competitors.” These individuals, lauded as the “greatest minds of all time,” shape our understanding of the universe, culture, and even ourselves. Their brilliance is seen as an unalloyed good, a beacon of human potential.

Yet, the elevation of these exceptional individuals, while often merited, carries a hidden cost – a ‘fame’s price’ that sometimes manifests as profound, even irreversible, harm. This harm isn’t always malicious or intentional; it can stem from the unintended consequences of influential ideas, the flawed application of novel methodologies, or the problematic societal archetypes that genius helps to foster. When we place certain minds on a pedestal, we must also critically examine the shadows they cast and the long-term impact of their contributions, even those made with the best intentions.

In this analytical exploration, adopting a clear and contextual Vox-style lens, we delve into the stories and legacies of eight individuals whose genius, though celebrated, also led to significant, and in some cases, irreversible harm. We will break down the ‘why’ behind these complex outcomes, exploring how their influential ideas, methodologies, or the very perceptions they helped shape, had profound and sometimes detrimental effects on society’s understanding of itself and its most brilliant members.

1. **Francis Galton: The Architect of Eugenics and the Peril of ‘Natural Ability’**Francis Galton, a towering intellectual figure of the 19th century and half-cousin to Charles Darwin, is widely “regarded as the founder of psychometry,” a field dedicated to the measurement of psychological traits. His groundbreaking work, particularly his 1869 publication “Hereditary Genius,” laid early foundations for understanding the inheritance of human characteristics. Galton hypothesized that “eminence is inherited from ancestors” and embarked on a study of eminent families in Britain, seeking to quantify the prevalence of genius through familial lines. His meticulous, if ultimately flawed, methodology deeply influenced the emerging fields of statistics and psychology.

Galton’s ideas were heavily influenced by his older half-cousin, Charles Darwin, and built upon the statistical work of Carl Friedrich Gauss and Adolphe Quetelet. While Gauss discovered the normal distribution, and Quetelet applied it to social statistics to define “the average man,” Galton took these concepts further. He “departed from Gauss in a way that became crucial to the history of the 20th century AD,” concluding that differences between the average and the upper end of the bell-shaped curve were due to a “non-random factor, ‘natural ability’.” He defined this as “those qualities of intellect and disposition, which urge and qualify men to perform acts that lead to reputation…a nature which, when left to itself, will, urged by an inherent stimulus, climb the path that leads to eminence.” This concept of an innate, quantifiable “natural ability” was central to his framework.

However, Galton’s work, despite its pioneering spirit, faced significant “criticisms include that Galton’s study fails to account for the impact of social status and the associated availability of resources in the form of economic inheritance, meaning that inherited ’eminence’ or ‘genius’ can be gained through the enriched environment provided by wealthy families.” This fundamental oversight highlighted a crucial flaw in his assumption that eminence was purely a matter of inherited biological traits, neglecting the profound influence of socio-economic factors. The idea that genius was solely an inherited, biological predisposition, rather than a complex interplay of nature and nurture, would have far-reaching and tragic consequences.

The most profound “irreversible harm” stemming from Galton’s influential work was his subsequent development of “the field of eugenics.” This pseudoscientific movement advocated for selective breeding to “improve” the human population, leading to discriminatory policies, forced sterilizations, and ultimately providing intellectual justification for horrific atrocities in the 20th century. Galton’s genius, celebrated for its rigor in measurement and statistical analysis, thus laid the groundwork for an ideology that caused immense suffering and irreparable damage to countless lives, demonstrating a stark example of the grave “price of fame” when intellectual curiosity veers into dangerous social engineering.

2. **Lewis Terman: The Imperfect Architect of Intelligence Measurement and the Misdirection of Talent**

Lewis Terman stands as another pivotal figure in the history of understanding genius, particularly through his pioneering contributions to intelligence testing. In his 1916 version of the Stanford–Binet test, Terman famously “chose ”near” genius or genius’ as the classification label for the highest classification.” His work quickly became influential, shaping educational practices and psychological assessments for decades. This formalization of intelligence into a quantifiable score, with a specific label for exceptional ability, profoundly impacted how society identified and categorized gifted individuals.

Beyond just classification, Terman dedicated a significant portion of his life to a comprehensive, longitudinal endeavor: the “Genetic Studies of Genius.” Beginning in “1926, Terman began publishing about a longitudinal study of California schoolchildren who were referred for IQ testing by their schoolteachers, which he conducted for the rest of his life.” This ambitious project aimed to track and understand the developmental trajectories of high-IQ children, a monumental undertaking intended to shed light on the nature of genius from an early age. His research, published in multiple volumes, served as a benchmark for subsequent studies on giftedness.

However, the very methodology and conclusions of Terman’s highly elevated study contained inherent flaws that led to significant “irreversible harm” in the understanding and identification of genius. The context explicitly notes a glaring oversight: “Two pupils who were tested but rejected for inclusion in the study (because their IQ scores were too low) grew up to be Nobel Prize winners in physics, William Shockley, and Luis Walter Alvarez.” This crucial detail reveals the limitations of Terman’s IQ-centric approach. While his system sought to define and capture genius, it fundamentally missed exceptional talent that did not conform to his predefined metrics, underscoring the inadequacy of IQ scores as the sole determinant of future eminence.

The “irreversible harm” caused by Terman’s influential work lies in the misdirection and narrow framing of genius that it initially fostered. By elevating IQ as the primary, and for a time, nearly exclusive, measure of intellectual potential, his research inadvertently led to the exclusion of truly brilliant minds from recognition and support. The Terman study’s findings, and its subsequent criticisms, ultimately informed the “current view of psychologists and other scholars of genius is that a minimum level of IQ (approximately 125) is necessary for genius but not sufficient, and must be combined with personality characteristics such as drive and persistence, plus the necessary opportunities for talent development.” This evolution in understanding highlights how Terman’s initial, flawed system necessitated a corrective, but not before countless individuals and educational systems had been influenced by its restrictive paradigm.

3. **Catherine M. Cox: The Perils of Retrospective IQ Estimation and Distorting Historical Genius**Working closely alongside Lewis Terman, Catherine M. Cox made her own significant, yet controversial, contribution to the study of genius. As a colleague within Terman’s extensive “Genetic Studies of Genius,” Cox undertook a monumental task detailed in “a whole book, The Early Mental Traits of 300 Geniuses, published as volume 2 of The Genetic Studies of Genius book series.” Her work aimed to apply psychological assessment retroactively, attempting to quantify the intellectual prowess of historical figures who, by definition, never took a modern IQ test. This ambitious project sought to bring scientific rigor to the study of historical eminence.

Cox’s methodology involved “analyz[ing] biographical data about historic geniuses” to estimate their childhood IQ scores. She meticulously combed through records, letters, and other historical accounts to infer the early intellectual abilities of figures ranging from philosophers to artists. Her approach was unprecedented in its scope, attempting to bridge the gap between contemporary psychometrics and historical scholarship to construct a comprehensive understanding of the early signs of genius across different eras. The sheer scale and intent of her work were testament to the prevailing belief in the power of quantitative measurement.

Despite the thoroughness of Cox’s study in exploring “what else matters besides IQ in becoming a genius,” her central methodology of estimating childhood IQs of historical figures “have been criticized on methodological grounds.” Critics highlighted the inherent biases and inaccuracies of such retrospective assessments, pointing out that “much error may creep into an experiment of this sort,” and that “the I.Q. assigned to any one individual is merely a rough estimate, depending to some extent upon how much information about his boyhood years has come down to us.” Furthermore, a critical observation was that “the more was known about a person’s youthful accomplishments, that is, what he had done before he was engaged in doing the things that made him known as a genius, the higher was his IQ.” This suggested a circularity and confirmation bias, where more documented early precocity led to higher estimated IQs, rather than an objective measure of innate ability.

The “irreversible harm” stemming from Cox’s work, despite its pioneering spirit, lies in the potential for perpetuating a distorted historical understanding of genius. By generating precise-looking, yet methodologically dubious, IQ scores for historical figures, her study inadvertently reinforced a narrow, quantitative definition of genius that could overshadow the nuanced contributions and contextual factors of these individuals. This approach, once elevated as a scholarly effort, contributed to a misleading narrative that emphasized a singular measure of intelligence, potentially trivializing the complex interplay of creativity, environment, and persistence that truly defines historical eminence, as later psychologists would acknowledge. It solidified an approach that, while thorough in some aspects, fundamentally misinterpreted the essence of historical intellectual contribution.

4. **Adolphe Quetelet: The ‘Average Man’ and the Effacement of Human Peculiarities**Adolphe Quetelet, a Belgian astronomer, mathematician, and sociologist, may not be as commonly recognized as a “genius” in the traditional sense, but his groundbreaking work in applying statistical methods to human characteristics profoundly influenced how we understand populations and individuals. His genius lay in translating complex mathematical theories, particularly Carl Friedrich Gauss’s normal distribution (the familiar bell-shaped curve), into a framework for analyzing social phenomena. He essentially pioneered “social physics,” believing that human behavior could be understood through statistical laws, much like natural phenomena. This innovative application marked a significant shift in scientific thought, moving from individual cases to population-level analysis.

Quetelet’s seminal contribution involved his discovery “that the bell-shaped curve applied to social statistics gathered by the French government in the course of its normal processes on large numbers of people passing through the courts and the military.” His initial foray into “criminology led him to observe ‘the greater the number of individuals observed the more do peculiarities become effaced…’.” From this observation, he conceptualized an ideal, statistical construct: “This ideal from which the peculiarities were effaced became ‘the average man’.” This concept, the ‘homme moyen’, became a cornerstone of his statistical approach, positing that by aggregating data, individual variations would cancel out, revealing a central tendency that represented the quintessential human.

This concept of the “average man” was not merely an academic exercise; it had a profound and influential impact on subsequent thinkers. Francis Galton, for instance, “was inspired by Quetelet to define the average man as ‘an entire normal scheme’; that is, if one combines the normal curves of every measurable human characteristic, one will, in theory, perceive a syndrome straddled by ‘the average man’ and flanked by persons that are different.” This direct lineage underscores how Quetelet’s statistical constructs provided a powerful conceptual tool for understanding human populations, and in particular, for Galton’s later, more controversial, theories of ‘natural ability’ and eugenics. The idea of a statistically ‘normal’ human being began to take root, influencing fields from medicine to social policy.

The “irreversible harm” associated with the elevation of Quetelet’s “average man” concept, while perhaps indirect, is nonetheless significant. By emphasizing the statistical norm and the “effacement of peculiarities,” his work inadvertently contributed to a reductionist view of human identity, where individual uniqueness could be overshadowed by population averages. This framework, when applied broadly, risks devaluing the very diversity that characterizes humanity, subtly paving the way for later social classifications that marginalized those who deviated from the statistical norm. While not malicious in intent, the profound influence of the “average man” concept on fields that later sought to ‘normalize’ or ‘optimize’ human populations represents a lasting impact on how we perceive and value individual differences within society.

Continuing our exploration into the complex legacies of brilliant minds, we turn now to how elevated philosophical concepts, influential theories, and pervasive archetypes associated with genius have profoundly shaped our understanding of human intelligence and, in some cases, inflicted lasting harm. The journey through the history of genius is not just a celebration of intellect, but a critical examination of its societal implications, revealing how even the most profound ideas can cast long shadows.

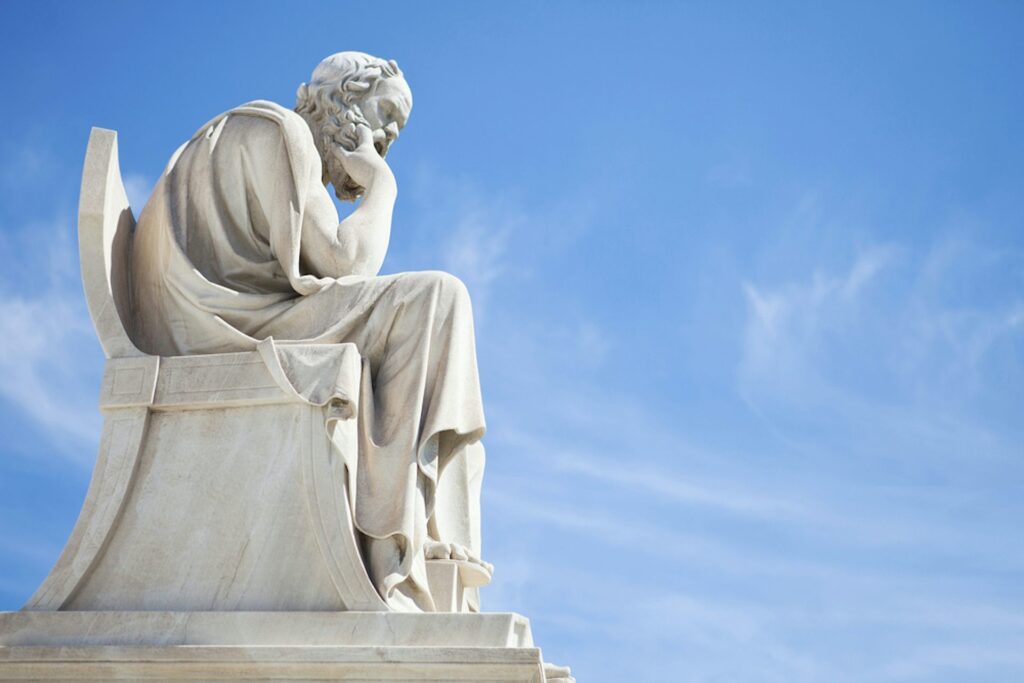

5. **Arthur Schopenhauer: The ‘Suffering Genius’ and the Devaluation of Mundane Life**Arthur Schopenhauer, a towering figure in German philosophy, offered a distinct and influential definition of genius that has resonated through centuries, significantly shaping cultural perceptions. For Schopenhauer, a genius is fundamentally characterized by an intellect that predominates over the “will” — a concept he believed to be much more pronounced in exceptional individuals than in the average person. This philosophical stance positioned the genius as someone operating on a higher plane of consciousness, capable of creating artistic or academic works that serve as objects of “pure, disinterested contemplation,” which he deemed the chief criterion of the aesthetic experience.

However, this elevated view of the intellect came with a problematic corollary. Schopenhauer explicitly linked the genius’s remoteness from mundane concerns with their brilliance, suggesting that such individuals often “display maladaptive traits in more mundane concerns.” He famously encapsulated this idea with the phrase that geniuses “fall into the mire while gazing at the stars,” an allusion to Plato’s dialogue Theætetus, where Socrates recounts Thales, the first philosopher, being ridiculed for such practical ineptitude. This vivid imagery profoundly contributed to a burgeoning archetype of the intellectual who is brilliant but utterly impractical, even dysfunctional, in everyday life.

The “irreversible harm” stemming from Schopenhauer’s influential philosophy, while not direct and policy-driven like eugenics, lies in its significant contribution to the pervasive “tortured genius” archetype. By philosophically legitimizing the idea that brilliance inherently entails a detachment from, or even an incompetence in, mundane affairs, Schopenhauer inadvertently fostered a cultural expectation that genius must be accompanied by suffering, social awkwardness, or even self-neglect. This narrative can subtly normalize maladaptive behaviors, suggesting they are a necessary trade-off for exceptional intellect, rather than conditions that might require support or intervention.

This philosophical elevation of detachment also risks devaluing the importance of well-rounded development, emotional intelligence, and practical competence for individuals with high intellect. It can create an isolating burden for those perceived as geniuses, encouraging them to embrace or even perform a persona of suffering or social ineptitude to align with a romanticized ideal. Consequently, Schopenhauer’s powerful philosophical concept, though intended to describe the unique nature of profound thought, has ironically contributed to a societal understanding that can hinder the holistic well-being and integrated functioning of brilliant individuals, perpetuating a harmful and narrow definition of human potential.

6. **Thomas Carlyle: The ‘Great Man Theory’ and the Cult of Infallible Genius**Thomas Carlyle, a prominent Scottish historian and philosopher, articulated a highly influential view of genius that centered on what became known as the “Great Man Theory.” In his work *Past and Present*, Carlyle described genius as “the inspired gift of God,” asserting that the “Man of Genius” possesses “the presence of God Most High in a man.” This perspective imbued exceptional individuals with an almost divine quality, suggesting that their talents and insights were not merely human capabilities but rather manifestations of a higher, sacred power. This elevated status extended to their actions, which, according to Carlyle, could manifest this divine presence in various forms, from a “transcendent capacity of taking trouble” to recognizing “how every object has a divine beauty in it” or possessing “an original power of thinking.”

Carlyle’s theory went further by identifying specific historical figures as exemplars of this divine genius, including Odin, William the Conqueror, and Frederick the Great. By placing such powerful and sometimes ruthless historical figures on a pedestal as “Men of Genius,” he implicitly suggested that their actions, even those involving conquest or authoritarian rule, were part of a divinely inspired trajectory. This framework, which views history as largely shaped by the actions of these extraordinary individuals, created a powerful narrative that celebrated singular brilliance as the primary engine of human progress, overshadowing collective efforts or systemic factors.

The “irreversible harm” caused by Carlyle’s “Great Man Theory” is significant and multifaceted. By elevating certain individuals to an almost unassailable, divinely sanctioned status, his philosophy fostered an unquestioning reverence that could, and often did, overlook or excuse the profound flaws, ethical compromises, and detrimental actions of these ‘great men.’ When genius is conflated with divine inspiration, it becomes difficult to hold such individuals accountable, potentially suppressing critical scrutiny and dissent. This can lead to a dangerous cult of personality, where the brilliance of a leader or innovator is seen as justification for any means to an end, regardless of the human cost.

Moreover, this influential theory profoundly distorted the broader understanding of human intelligence and progress. By attributing societal advancements almost exclusively to the singular vision and will of a few exceptional individuals, Carlyle’s work inadvertently diminished the contributions of countless others, from collaborators and researchers to social movements and evolving societal structures. It perpetuated a hierarchical view of intellect where only a select few are deemed capable of true innovation, thereby hindering a more democratic and inclusive understanding of how progress actually occurs. The legacy of the ‘Great Man Theory’ thus lies in its potential to justify authoritarianism and to undermine the critical evaluation necessary for ethical leadership and truly collective human advancement.

7. **Bertrand Russell: The Vulnerability of Genius and Societal Indifference**Bertrand Russell, the eminent British philosopher and logician, offered a more nuanced and somber perspective on genius, focusing less on its intrinsic nature and more on its precarious existence within society. Russell maintained that genius entails an individual possessing “unique qualities and talents that make the genius especially valuable to the society in which he or she operates, once given the chance to contribute to society.” This viewpoint acknowledged the immense potential benefit that extraordinary minds could bring to humanity, emphasizing their unique capacity to push boundaries and enrich collective knowledge and culture. It framed genius as a societal asset, a precious resource that requires careful stewardship.

However, Russell’s philosophy carried a crucial and often overlooked caveat that highlights a profound “irreversible harm.” He firmly believed that it is entirely possible for such geniuses to be “crushed in their youth and lost forever when the environment around them is unsympathetic to their potential maladaptive traits.” Critically, Russell “rejected the notion he believed was popular during his lifetime that, ‘genius will out’.” This was a direct challenge to the comforting but ultimately false idea that true brilliance would inevitably find a way to emerge, regardless of circumstances. He posited that many potential geniuses might never reach their full potential, not due to a lack of innate ability, but due to a hostile or unsupportive environment that fails to understand or accommodate their unique developmental needs and sometimes unconventional characteristics.

The “irreversible harm” illuminated by Russell’s perspective is the tragic and systemic loss of human potential due to societal indifference or an inability to nurture divergent minds. The persistent myth that “genius will out” fostered a complacency, effectively dismissing the critical need for tailored educational systems, supportive familial structures, and tolerant social environments that can recognize and cultivate exceptional talent, especially when it manifests with “maladaptive traits” like social awkwardness, intense focus, or unconventional thought processes. This mindset allows potentially transformative minds to be overlooked, misunderstood, or even actively suppressed, rather than guided and empowered.

Russell’s insights underscore a profound societal failing: the systemic squandering of immense human resources. By not providing the necessary opportunities and understanding, society implicitly chooses to sacrifice future innovations, artistic masterpieces, or paradigm-shifting discoveries. His philosophy serves as a stark warning against the romanticized notion of an innate, unassailable brilliance that can overcome any obstacle, revealing instead its fragile dependency on external support and recognition. The harm, in this case, is not an active infliction of suffering but a passive, yet devastating, loss that leaves humanity poorer for what might have been.

8. **Pop Culture’s ‘Tortured Genius’ Archetype: Glorifying Suffering and Misrepresenting Mental Health**

Beyond philosophical treatises and scientific studies, the concept of genius takes on a vivid, often simplified, life in literature and pop culture. In these narratives, geniuses are frequently stereotyped, primarily depicted as either the “wisecracking whiz” or, more pervasively and problematically, the “tortured genius.” This latter archetype has become a deeply ingrained motif, presenting the brilliant individual as an “imperfect or tragic hero who wrestles with the burden of superior intelligence, arrogance, eccentricities, addiction, awkwardness, mental health issues, a lack of social skills, isolation, or other insecurities.” These characters, from Dr. Bruce Banner to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in *Amadeus* and Dr. John Nash in *A Beautiful Mind*, are shown regularly experiencing existential crises, struggling to overcome personal challenges to harness their abilities, or succumbing to their own tragic flaws and vices.

This “common motif repeated throughout fiction” carries a significant and often unacknowledged “irreversible harm.” By romanticizing suffering and associating mental illness with exceptional brilliance, pop culture inadvertently creates a misleading and dangerous narrative. It suggests that psychological distress, social alienation, or even addiction are not merely incidental to genius but are, in some twisted way, necessary ingredients for it. This portrayal can foster an environment where individuals with exceptional abilities feel pressured to embody these negative traits, or worse, perceive their own genuine mental health struggles as validation of their genius rather than as conditions requiring professional help.

Furthermore, the “tortured genius” archetype perpetuates a harmful stereotype that those who deviate from societal norms or exhibit intense intellectual focus must inevitably be emotionally or socially dysfunctional. This can lead to a lack of empathy and understanding from society, which might dismiss or even glorify the struggles of brilliant individuals rather than offering meaningful support. It blurs the lines between genuine mental health conditions, which require treatment, and the superficial eccentricities often portrayed as hallmarks of creativity, thereby trivializing serious illnesses.

Ultimately, the pervasive nature of this archetype in popular media contributes to a distorted societal understanding of both genius and mental health. It can isolate brilliant individuals, reinforce stigmas around psychological well-being, and hinder a holistic appreciation of human potential that encompasses both exceptional intellect and personal well-being. By celebrating the ‘tortured’ aspect, pop culture unwittingly undermines efforts to create supportive environments where genius can thrive without personal devastation, inadvertently causing lasting harm to individuals and the broader conversation around mental health and giftedness.

As we conclude this profound journey into the shadows cast by celebrated brilliance, it becomes clear that the narratives surrounding genius are far more complex than mere admiration. The figures and concepts we’ve explored—from the statistical reductionism of Quetelet to the romanticized suffering of pop culture’s ‘tortured genius’—each highlight a crucial lesson: the elevation of intellect, while inspiring, demands rigorous ethical and contextual scrutiny. To truly understand and nurture genius, we must move beyond simplistic accolades and recognize the hidden costs, the inadvertent harms, and the profound responsibilities that come with exceptional minds. Only by doing so can we foster an environment where brilliance can genuinely serve humanity, unburdened by the very pedestals we construct.