The name Malcolm X evokes a complex tapestry of revolutionary thought, fierce advocacy, and a journey of profound personal transformation. From his humble beginnings as Malcolm Little to his powerful presence as a Muslim minister and human rights activist, his life was a testament to the turbulent racial landscape of 20th-century America. He became a beacon for Black empowerment, a figure both celebrated and controversial, whose pursuit of racial justice continues to resonate decades after his untimely death. Many questions surrounding his life and passing remain deeply etched in history.

For countless observers, his story is synonymous with the broader civil rights movement, yet his approach often stood in stark contrast to the non-violent tenets espoused by others. Malcolm X challenged the status quo with an uncompromising voice, advocating for Black self-reliance and relentlessly critiquing the systemic injustices faced by African Americans. His narrative is not merely one of activism, but also a deeply personal saga of evolution, marked by intellectual awakening, spiritual conversion, and ultimately, a tragic and violently cut short end.

This article embarks on an in-depth investigation into the life and passing of Malcolm X, meticulously delving into the critical junctures that shaped his ideology and ultimately led to the enduring mystery surrounding his assassination. We will meticulously retrace his steps, from his challenging childhood and years of transgression to his radical transformation within prison walls and his meteoric rise as a compelling orator, exploring the profound forces that propelled him to national prominence and the internal conflicts that foreshadowed his eventual split from the Nation of Islam. This exploration will illuminate the multifaceted individual behind the iconic figure, offering a richer understanding of his journey and the unresolved questions of his legacy.

1. **Early Life and Childhood Struggles**Born Malcolm Little on May 19, 1925, in Omaha, Nebraska, Malcolm X was the fourth of seven children, emerging from a family deeply rooted in early Black activism. His parents, Grenada-born Louise Little and Georgia-born Earl Little, were ardent admirers of Pan-African activist Marcus Garvey. Earl, an outspoken Baptist lay speaker, was a local leader of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), while Louise served as its secretary and “branch reporter,” diligently sending news of local UNIA activities to *Negro World*. This early environment was crucial, as they actively inculcated values of self-reliance and Black pride in their children.

However, their childhood was profoundly marred by racial antagonism and relentless tragedy. Due to Ku Klux Klan threats, Earl’s UNIA activities were deemed “spreading trouble,” forcing the family to relocate first to Milwaukee in 1926, and shortly thereafter to Lansing, Michigan. There, the family was subjected to frequent harassment by the Black Legion, a white racist group that Earl explicitly accused of burning their family home in 1929. These traumatic events cast a long, dark shadow over Malcolm’s formative years, compounded by his later recollection that White violence had also claimed the lives of four of his father’s brothers, demonstrating a pervasive pattern of racial terror.

When Malcolm was just six years old, his father died in what has been officially ruled a streetcar accident, though his mother Louise firmly believed Earl had been murdered by the Black Legion. The lingering rumors that White racists were responsible for his father’s death were widely circulated and deeply disturbing to young Malcolm. As an adult, he would express conflicting beliefs on this unsettling question, a reflection of the trauma. Adding to the family’s instability, a man Louise had been dating vanished from her life when she became pregnant with his child in 1937, leading to her nervous breakdown in late 1938 and subsequent commitment to Kalamazoo State Hospital. The children were separated and sent to various foster homes, a painful rupture in their lives that would only be healed 24 years later when Malcolm and his siblings secured her release.

Malcolm attended West Junior High School in Lansing and then Mason High School in Mason, Michigan, initially excelling academically. He harbored an aspiration at the time to practice law, a goal that spoke to his keen intellect and desire for justice. However, his dreams were cruelly dashed in 1941 when he dropped out of high school after a white teacher delivered a devastating blow, telling him that practicing law was “no realistic goal for a nigger.” This blunt and demeaning dismissal deeply affected him, leading him to conclude, as he later recalled, that the White world offered no place for a career-oriented Black man, regardless of his talent, pushing him onto a different, far more perilous path.

2. **Criminal Career and Incarceration**Following his premature departure from high school, Malcolm Little embarked on a turbulent seven-year period of his life marked by a variety of jobs, which quickly became intertwined with a dangerous descent into a criminal lifestyle. From the age of 14 to 21, he resided with his half-sister Ella Little-Collins in Roxbury, a largely African American neighborhood of Boston. This move to a bustling urban environment set the stage for his deep involvement in activities that would define his early adulthood and lead him down a path far removed from his childhood aspirations of academic achievement.

In 1943, after a short but impactful time in Flint, Michigan, he relocated to the vibrant, yet challenging, Harlem neighborhood of New York City. It was there that Malcolm found employment on the New Haven Railroad, but simultaneously became deeply entrenched in a world of illicit activities. He engaged in drug dealing, gambling, racketeering, robbery, and pimping, immersing himself in the underworld of the city. During this period, he befriended John Elroy Sanford, a fellow dishwasher at Jimmy’s Chicken Shack, who aspired to be a professional comedian; both men had reddish hair, so Sanford was called “Chicago Red” after his hometown, and Malcolm was known as “Detroit Red” – a nickname that would follow him. Years later, Sanford would achieve fame as comedian and actor Redd Foxx.

His increasingly brazen criminal exploits eventually caught up with him. In late 1945, Malcolm returned to Boston, where he and four accomplices committed a series of burglaries targeting wealthy White families, escalating the scale of his transgressions. His recklessness ultimately led to his arrest in 1946 when he was apprehended while picking up a stolen watch he had left at a shop for repairs. This seemingly minor misstep resulted in a severe consequence: in February, he began serving a sentence of eight to ten years at Charlestown State Prison for larceny and breaking and entering, abruptly halting his criminal career and ushering in a new, transformative chapter.

During his incarceration, he was transferred between different facilities, serving 15 months at Concord Reformatory before transferring again to Norfolk Prison Colony in 1947. These years behind bars would prove to be a pivotal turning point, forcing a period of intense reflection and ultimately leading to a profound transformation that few could have anticipated. This chapter, born of desperation and poor choices, paradoxically became the crucible in which his future as a revolutionary leader would be forged, setting him on an entirely new trajectory away from the streets and towards intellectual and spiritual awakening.

3. **Discovery of Nation of Islam in Prison**The confines of prison, far from breaking Malcolm Little’s spirit, became the unlikely setting for his profound intellectual and spiritual awakening. It was within these walls that he encountered fellow convict John Bembry, a self-educated man whose depth of knowledge deeply impressed Malcolm. Bembry, whom Malcolm would later describe as “the first man I had ever seen command total respect … with words,” ignited in him a “voracious appetite for reading,” transforming his idle time into an opportunity for intense self-improvement and learning. Months passed without him even thinking about being imprisoned, as he later recalled, stating, “In fact, up to then, I had never been so truly free in my life.”

During this pivotal period, several of his siblings began writing to him about the Nation of Islam (NOI), a relatively new religious movement that was rapidly gaining traction. The NOI’s teachings centered on Black self-reliance and, ultimately, the return of the African diaspora to Africa, where they would be free from White American and European domination. Initially, Malcolm showed scant interest in these letters, perhaps still grappling with his own identity and past struggles, finding their message distant from his immediate reality.

A significant turning point arrived in 1948 when his brother Reginald penned a potent message: “Malcolm, don’t eat any more pork and don’t smoke any more cigarettes. I’ll show you how to get out of prison.” This simple yet powerful directive had an almost instantaneous effect; Malcolm almost instantly quit smoking and began to refuse pork, demonstrating a sudden readiness for discipline and a profound search for a path to freedom, not just from physical bars, but from the spiritual and mental chains he felt had bound him.

Following a visit during which Reginald detailed the group’s teachings, including the controversial notion that White people are considered devils, Malcolm initially struggled deeply to accept this belief. Over time, however, Malcolm reflected on his past relationships with White individuals, and through this introspection, concluded that they had all consistently been marked by dishonesty, injustice, greed, and hatred. This personal validation, combined with his existing hostility toward Christianity — which had earned him the prison nickname “Satan” — made him profoundly receptive to the message of the Nation of Islam, leading him to embrace its tenets and begin a regular, meaningful correspondence with its leader, Elijah Muhammad, initiating a new, transformative phase of his life and identity.

4. **Rapid Ascent as Nation of Islam Minister**Upon his parole in August 1952, Malcolm X — now embracing the “X” to symbolize his unknown African ancestral surname and rejecting “the white slavemaster name of ‘Little'” — wasted no time in fully immersing himself in the Nation of Islam. His first significant action was to visit Elijah Muhammad in Chicago, solidifying his commitment to the organization and its leader. His dedication, razor-sharp intellect, and natural charisma quickly became apparent, setting him on a swift and meteoric trajectory within the Nation’s ranks.

By June 1953, he was named assistant minister of the Nation’s Temple Number One in Detroit, a clear and early sign of the trust and recognition he was earning from Muhammad. His organizational prowess was equally impressive and rapidly demonstrated; later that same year, he established Boston’s Temple Number 11, strategically expanding the Nation’s footprint. The following year, in March 1954, he expanded Temple Number 12 in Philadelphia, consistently demonstrating his ability to grow the Nation’s presence across different cities and attract new followers with his compelling message.

Just two months after his Philadelphia success, Malcolm X was selected to lead Temple Number 7 in Harlem, a crucial and highly visible outpost for the Nation. Under his dynamic leadership, its membership rapidly expanded, transforming it into one of the organization’s most vibrant and influential centers. His powerful sermons, articulate arguments, and unwavering conviction resonated deeply with thousands of African Americans in northern and western cities who were weary of waiting for justice, equality, and respect, and who felt that he articulated their complaints better than the mainstream civil rights movement.

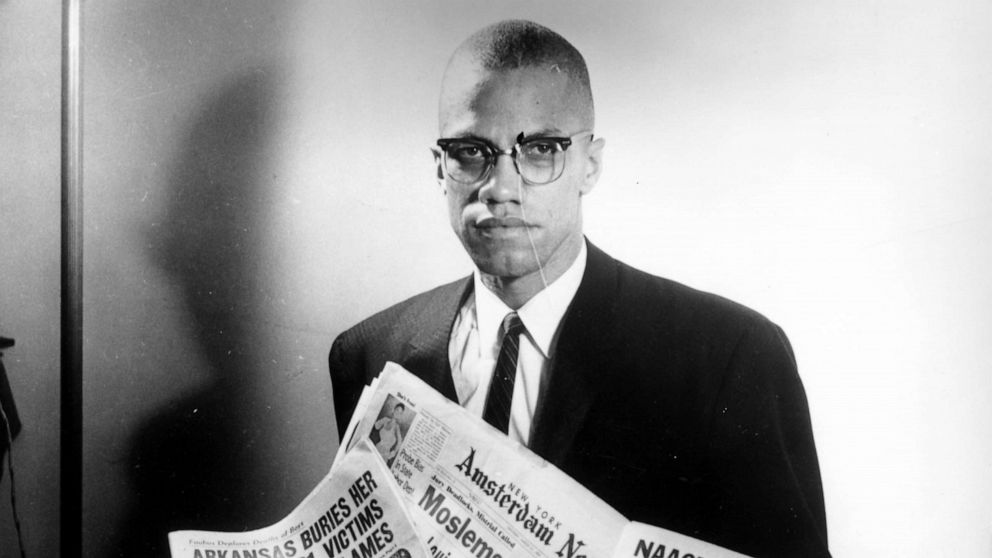

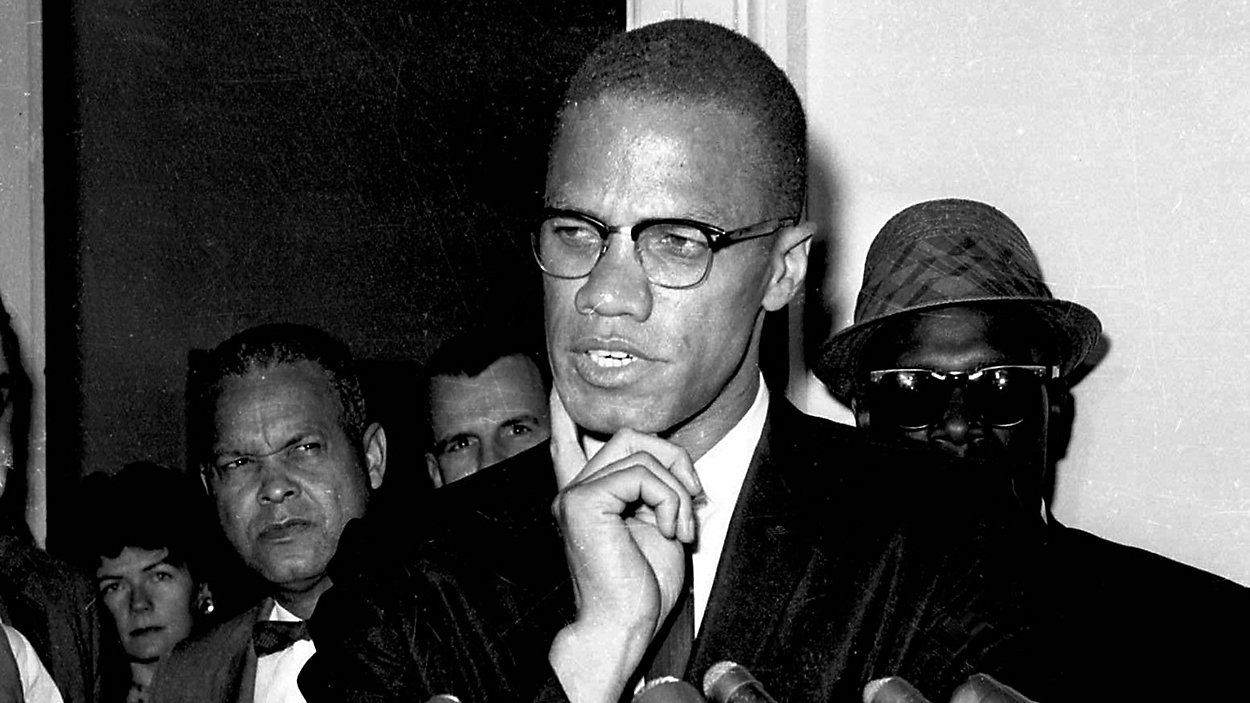

Beyond his exceptional skill as a speaker, Malcolm X possessed an impressive and commanding physical presence. He stood 6 feet 3 inches (1.91 m) tall and weighed about 180 pounds (82 kg), a stature that added to his aura of authority. One writer described him as “powerfully built,” and another as “mesmerizingly handsome … and always spotlessly well-groomed.” This potent combination of intellect, eloquence, and striking appearance made him an irresistible force, effectively making him the public face of the Nation of Islam for 12 years and largely credited with helping the group’s dramatic increase in membership from around 1,200 to between 50,000 and 100,000 members by the early 1960s, even as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) opened a file on him in 1950 and began surveillance in 1953, turning its attention from his possible communist associations to his rapid ascent in the Nation of Islam.

5. **Advocacy and Controversial Teachings with NOI**During his influential tenure with the Nation of Islam from his adoption of the faith in 1952 until his dramatic break in 1964, Malcolm X was the most prominent and articulate voice promoting the organization’s distinct and often controversial teachings. These core beliefs included the assertion that Black people were the “original people of the world,” a powerful message of inherent worth and historical significance that resonated deeply with his African American audiences, fostering a profound sense of pride and identity. He also vehemently taught that White people were “devils,” a highly provocative notion that, while widely criticized, resonated with those who had experienced centuries of systemic racism, oppression, and violence at the hands of White society.

Furthermore, he propagated the belief in the imminent demise of the White race, a prophecy that underscored the Nation’s vision of Black liberation and self-determination, offering a sense of eventual triumph. While these teachings led some, like Louis E. Lomax, to claim that “those who don’t understand biblical prophecy wrongly label him as a racist and as a hate teacher, or as being anti-White or as teaching Black Supremacy,” his words undeniably stirred strong reactions and positioned the Nation of Islam firmly outside the mainstream civil rights movement, advocating for a separate and distinct path for Black Americans. The Nation of Islam, notably, forbade its members from participating in voting and other aspects of the political process, a stance that further alienated them from traditional civil rights goals.

Malcolm X was equally and often more ferociously critical of the mainstream civil rights movement and its leaders. During this period, he infamously denounced Martin Luther King Jr. as a “chump,” and frequently referred to other civil rights leaders as being “stooges” of the White establishment, highlighting his profound skepticism of any efforts towards racial integration. He was strongly against any kind of racial integration, believing it to be a false solution. He asserted that the civil rights movement’s strategy of nonviolence was ineffective, arguing instead that Black people should be prepared to defend and advance themselves “by any means necessary,” a phrase that underscored his militant stance and call for self-defense.

His disdain for integration and traditional civil rights efforts was particularly evident in his biting comments on the 1963 March on Washington, which he famously derided as “the farce on Washington.” He expressed bewilderment, stating he did not know why so many Black people were excited about a demonstration “run by whites in front of a statue of a president who has been dead for a hundred years and who didn’t like us when he was alive.” Malcolm X advocated for the complete separation of African Americans from Whites, proposing that African Americans should return to Africa and that, in the interim, a separate country for Black people in America should be created, articulating the frustrations of many who felt that the civil rights movement was too slow and too conciliatory, and his speeches had a powerful effect on these audiences.

6. **The Hinton Johnson Incident**The American public’s awareness of Malcolm X dramatically heightened in 1957 following a brutal and highly publicized incident involving Hinton Johnson, a Nation of Islam member, who was severely beaten by two New York City police officers. On April 26, Johnson, along with two other passersby — also Nation of Islam members — witnessed the officers assaulting an African American man with nightsticks. Their attempt to intervene, by shouting, “You’re not in Alabama … this is New York!” was met with immediate and violent retaliation; one of the officers turned on Johnson, beating him so severely that he suffered brain contusions and subdural hemorrhaging. All four African American men were subsequently arrested.

Upon being alerted by a witness, Malcolm X swiftly responded to the developing crisis. Accompanied by a small group of Muslims, he went directly to the police station and demanded to see Johnson. Police initially denied that any Muslims were being held, attempting to stonewall his efforts. However, as the crowd outside the station grew to an estimated five hundred people, their resolve softened, and Malcolm X was permitted to speak with the injured Johnson. Demonstrating his organizational skills and insistence on due process, Malcolm X then insisted on arranging for an ambulance to transport Johnson to Harlem Hospital for urgent medical attention.

The situation escalated dramatically upon Johnson’s return to the police station after receiving his medical treatment, by which time approximately four thousand people had gathered outside, their presence a silent, powerful testament to Malcolm X’s influence. Inside, Malcolm X and an attorney worked to arrange bail for two of the Muslims. Johnson, however, remained unbailed, with police stating he could not return to the hospital until his arraignment the following day, an unacceptable condition to Malcolm X. Recognizing the impasse and the highly charged atmosphere, Malcolm X emerged from the station house and gave a distinct hand signal to the amassed crowd. In a testament to his immense authority and the disciplined nature of his followers, Nation members silently dispersed, followed by the rest of the crowd, leaving the officers stunned and unnerved by the coordinated power.

One police officer, undoubtedly rattled by the display of such organized influence, remarked to the *New York Amsterdam News*: “No one man should have that much power.” This incident proved to be a significant turning point, not only in solidifying Malcolm X’s public image as a formidable and commanding leader but also in drawing the unwelcome, intensified attention of law enforcement. Within a month, the New York City Police Department initiated surveillance on Malcolm X, and made inquiries with authorities in other cities in which he had lived, and prisons in which he had served time, signaling the start of intense scrutiny that would follow him for the remainder of his life. A grand jury declined to indict the officers who beat Johnson, leading Malcolm X to send an angry telegram to the police commissioner. Soon thereafter, the police department assigned undercover officers to infiltrate the Nation of Islam, marking the beginning of a prolonged and invasive surveillance campaign.