The landscape of America holds countless stories, some etched deeply into monuments and textbooks, others whispered by the earth itself, waiting for careful ears to listen. Beneath the bustling cities and quiet farmlands lie significant chapters of our past, particularly concerning the lives, deaths, and enduring spirits of enslaved Africans. These narratives, often deliberately obscured, are now being brought to light through the profound discoveries of slave cemeteries across the nation, challenging long-held assumptions and providing irrefutable evidence of the lives lived and lost.

These sacred grounds are not merely archaeological sites; they are powerful testaments to human resilience, enduring injustice, and the urgent need to reclaim forgotten histories. They offer tangible connections to individuals whose contributions shaped the very foundations of American society, yet whose personal stories were systematically erased. From Georgia’s cotton fields to New York’s sprawling metropolis, these cemeteries are reshaping our understanding of the scale and impact of slavery, demanding that we acknowledge the full, complex tapestry of our heritage.

1. The Newnan Slave Cemetery: A Landmark Discovery in the Antebellum South

The narrative of the Newnan Slave Cemetery emerges from the heart of Georgia’s booming 19th-century cotton trade, an economic engine that fueled a significant Black population, roughly “50 percent” of Newnan’s residents by “1828.” An “1828 map shows the burial grounds were adjacent to property owned by slave owner Andrew Berry,” a poignant illustration of the interconnected, yet deeply unequal, lives within the system of slavery. For generations, this sacred ground lay in relative obscurity, a silent witness to a painful past.

The cemetery’s modern rediscovery began in “1999, when the mayor was alerted to the land’s history.” This critical intervention halted ongoing excavation work and led to “an archeological survey of the area.” Utilizing “ground-penetrating radar,” researchers made a profound discovery: “249 graves without tombs, just leaf-covered depressions, slightly hollow in the earth.” This digital revelation unveiled a physical reality, confirming the existence of a substantial, forgotten burial ground.

This finding proved to be monumental, as researchers “realized that it was the largest slave cemetery in the Antebellum South.” The scale of burials here offers an unprecedented window into the human cost of the cotton industry. Moreover, the graves, “arranged in clusters, perhaps indicating family groups,” speak to the enduring human need for kinship and remembrance, even in death, under the brutal institution of slavery.

2. **The UNC Charlotte W.T. Alexander Plantation Slave Cemetery: A Personal Journey of Rediscovery**

The story of the UNC Charlotte W.T. Alexander Plantation Slave Cemetery provides a compelling, localized account of rediscovery, highlighting the dedicated efforts required to bring marginalized histories to light. This site, now part of a university landscape, was once the expansive “W.T. Alexander plantation,” spanning “935 acres at its height” and where “at least 30 individuals” were enslaved. Its integration into the university’s fabric, through the 1957 donation of “five acres” for a campus road, intertwines past and present in a profound way.

The initial challenge in acknowledging this history lay in the elusive nature of the cemetery itself, with “details about the location and accessibility outdated and inconclusive.” It required the persistent work of “a team of Charlotte Urban Institute staff” to actively seek out and confirm the site. Their journey began with a “historical marker at the entrance to the Thornberry Apartments,” which explicitly noted the “WT Alexander Plantation (1824-1865) Slave Cemetery,” including the graves of “Solomon and Violet Alexander,” located “approximately 800 feet south.”

Following these directions, the team eventually located “a wrought iron fence around a section of woods next to the apartment complex’s tennis courts,” with “a sign on the locked entrance” confirming their discovery. Once inside, they observed “at least 30 graves marked with rocks at the head and foot,” with one stone possibly engraved “S.A. V.A.” These simple, yet powerful, markers provide tangible evidence of the lives of the enslaved, emphasizing the importance of dedicated efforts to reclaim these vital, personal histories.

3. The African Burial Ground National Monument: A Monumental Revelation in New York City

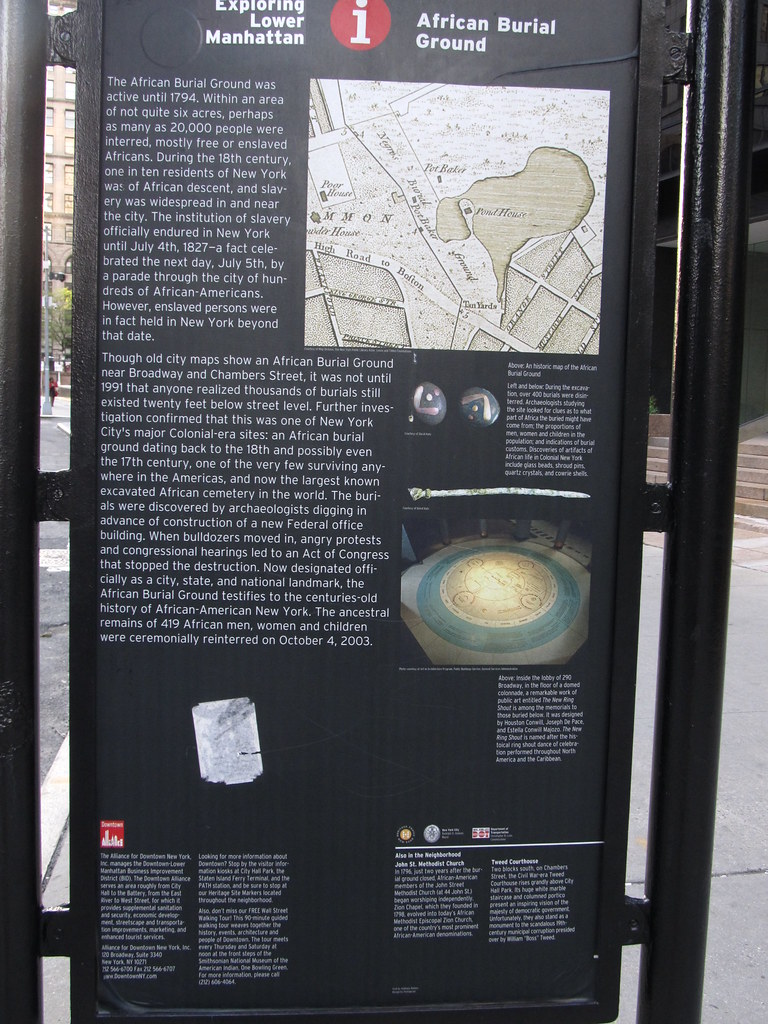

In the vibrant heart of Lower Manhattan, an extraordinary site known as the African Burial Ground National Monument unveils a critical, long-obscured chapter of American history. This sacred ground holds the remains of “more than 419 Africans buried during the late 17th and 18th centuries,” a mere fraction of what historians estimate was “the largest colonial-era cemetery for people of African descent,” possibly containing “10,000–20,000 burials.” This monumental scale redefines our understanding of New York City’s origins.

The discovery and subsequent study of this “five to six acre site” has been hailed as “the most important historic urban archaeological project in the United States.” This recognition underscores its immense value in bringing to light the forgotten history of enslaved Africans who were “integral to its development.” By “the American Revolutionary War, they constituted nearly a quarter of the population in the city,” a demographic reality that challenges simplistic narratives of Northern colonial life.

New York City, perhaps surprisingly, played a pivotal role in the institution of slavery, possessing “the second-largest number of enslaved Africans in the nation after Charleston, South Carolina.” The African Burial Ground thus stands as a profound testament to this historical truth. Its designation as “a National Historic Landmark in 1993 and a national monument in 2006 by President George W. Bush” represents a monumental step towards acknowledging the foundational role of enslaved Africans in the nation’s history.

4. The Historical Context of Slavery in New York City

Understanding the African Burial Ground requires a deep dive into the pervasive history of slavery within New York City. The city’s very foundation was built upon the labor of enslaved Africans, a grim legacy that commenced “in about 1626” with their introduction by the “Dutch West India Company in New Netherland.” Early names like Paul D’Angola and Simon Congo reflect their places of origin, highlighting the forced displacement from Africa.

Under early Dutch rule, some enslaved individuals managed to achieve “freedom or ‘half-freedom,'” an aspiration exemplified by “Paul D’Angola and his companions” in “1643,” who “petitioned the Dutch West India Company for their freedom,” and were granted land. However, this limited flexibility vanished when the “English seized New Amsterdam in 1664,” renaming it New York. The new administration quickly imposed “more restrictive” rules, “rescind[ing] many of the former rights and protections of enslaved residents,” solidifying a harsher system of bondage.

By the 18th century, slavery was deeply entrenched; “in 1703, 42 percent of New York’s households had slaves,” a higher proportion “than Philadelphia and Boston combined.” Enslaved people were not only domestics but also “skilled artisans and craftsmen,” vital to the city’s economy. This significant population meant that “by 1775, New York City had the largest number of enslaved residents of any settlement in the Thirteen Colonies excepted Charles Town, South Carolina,” profoundly shaping its development and underscoring the necessity of acknowledging this complex past.

Read more about: Unearthing Trauma: The Enduring Narrative of ‘Beloved’ for a Dark and Gritty Live-Action Reboot

5. The Transformation of Burial Practices and Spaces for Enslaved Africans in NYC

The African Burial Ground’s story is inextricably linked to the evolving, and increasingly discriminatory, burial practices imposed upon enslaved Africans in colonial New York City. Initially, public burial grounds, like “the north graveyard of Trinity Church” in the late 1600s, were nominally “open to all for a fee, including to enslaved Africans.” Some even chose to bury their dead “just south of the public burial ground to avoid the fee,” revealing agency even in these constrained circumstances.

A significant and regressive shift occurred after “Trinity was established as a parish church in 1697.” The church vestrymen, consolidating control, passed a resolution “on October 25, 1697,” explicitly stating: “‘That after the Expiration of four weeks from the dates hereof no Negro’s be buried within the bounds & Limitts of the Church Yard of Trinity Church…'” This ordinance effectively barred Africans from interment within city limits, an egregious act of segregation extending even to death.

This prohibition necessitated a new, marginalized resting place. What became known as the “Negro’s Burial Ground” was established “on what was then the outskirts of the developed town, just north of present-day Chambers Street.” This 6.6-acre site, first utilized around “1712,” became the designated, yet segregated, cemetery for enslaved and freed people of African descent, a poignant reflection of their societal exclusion. Its very existence marks a painful transformation of dignity, even in their final resting places.

6. The Long-Forgotten History: Early Discoveries and the Silencing of Narratives

The African Burial Ground’s full story isn’t just about its recent rediscovery, but also about the many times it was uncovered and then deliberately, or inadvertently, forgotten. After the city officially “closed the cemetery in 1794,” the area was “platted for development.” Remarkably, the act of covering the site with “up to 25 feet (7.6 metres) of landfill” for urban construction inadvertently preserved the burials, turning the ground into a historical time capsule.

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, physical evidence of the cemetery occasionally surfaced, yet these finds were consistently dismissed. “The site’s earliest discovery in the early 19th century seems to have aroused little interest.” Homeowner James Gemmel, whose house stood at “290 Broadway,” found “many human bones” while digging his cellar, but “assumed that he had discovered a potter’s field.” This initial dismissal foreshadowed a pattern of ignorance or indifference.

Later, in “1897, when the building at 290 Broadway was demolished,” workers “found a large number of human bones.” Yet, instead of sparking serious inquiry, these remains were treated with shocking disrespect. “Many bones were taken as souvenirs by so-called relic hunters,” and conclusions about their origin were often speculative, ranging from the “1741 incident” of slave executions to vague notions of “Dutch or Indian origin.” These episodes underscore a systemic failure to recognize and honor the history of enslaved Africans.

7. The Battle for Recognition: Community Activism and the Preservation of Sacred Ground

The definitive recognition of the African Burial Ground as a sacred national monument was not an easy process; it was fiercely fought for by dedicated community activists. The catalyst was the “October 8, 1991,” announcement by the federal General Services Administration (GSA) of “8 intact burials” during excavation for a new federal office building. This discovery immediately contradicted the agency’s earlier “environmental impact statement (EIS) … which had predicted that human remains would not be found,” sparking justified outrage.

The GSA initially tried to push forward with construction, prioritizing “pressure of construction costs” over archaeological integrity and community concerns. However, the African-American community swiftly rallied, asserting that they were “not being sufficiently consulted” and that the discoveries demanded “a better archaeological project design.” The situation intensified when “in 1992, activists staged a protest at the site,” especially after learning “some intact burials were broken up during construction excavation.” These protests successfully forced “GSA [to] halt construction.”

This sustained pressure led to significant federal intervention. In “1992, the House Subcommittee on Public Works held budget hearings,” compelling a critical change in direction. Crucially, control of the burial site was “transferred from an archaeological firm in the city to the physical anthropologist Michael Blakey and his team at Howard University,” a historically Black institution. This empowered African-American scholars to lead the study of their ancestors’ remains, marking a profound victory in the battle for historical justice and self-determination, and ensuring appropriate reverence for these sacred grounds.

8. Scientific Insights from the Howard University Studies

The pivotal transfer of control over the African Burial Ground to the physical anthropologist Michael Blakey and his team at Howard University marked a profound shift. This move, to a historically Black institution, ensured that African-American scholars would lead the study of their ancestors’ remains, injecting a much-needed perspective and reverence into the research. It was a victory not just for archaeology, but for historical justice, giving voice to a long-silenced past.

The Howard University team approached their immense task with a clear set of questions, formulated in consultation with the community. These inquiries sought to unravel the cultural background and origins of the buried population, trace the cultural and biological transformations from African to African-American identities, assess the quality of life under enslavement, and identify modes of resistance. This community-driven research design underscored a commitment to understanding the full human experience embedded within these remains.

The excavations ultimately unearthed the intact remains of 419 individuals—men, women, and children of African descent—each buried individually in wooden boxes. The absence of mass burials speaks to a degree of care in their final rites, even under horrific circumstances. A poignant and sobering finding was that nearly half of these individuals were children under the age of 12, a stark indicator of the brutal mortality rates endured by enslaved populations.

Further forensic studies by the Howard University team delved into the specifics of their lives and deaths. Analyses of the remains offered crucial insights into nutrition, diseases prevalent at the time, and other indicators of general living conditions for both enslaved and free Black individuals. Some burials even contained items, such as a silver pendant found with a child, and revealed cultural markers like filed teeth, connecting these individuals directly to African traditions and rituals.

Read more about: Beyond the Blockbuster Star: Meet the Incredible Family Behind Tom Hanks, From His Adventurous Siblings to His Supportive Parents!

9. The Painful Truth: Abuse and Desecration of the Burial Ground

The story of the African Burial Ground is not solely one of rediscovery and reverence; it also encompasses a deeply disturbing history of abuse and desecration, even after its official closure in 1794. Archaeologists uncovered a substantial amount of industrial waste and ceramics during excavations, suggesting that the sacred ground had been treated as a dumpsite by Europeans during the 18th century, a stark indicator of societal disregard.

Even more tragically, the site was subjected to grave robbing and looting during this period, a horrifying violation of the resting places of the deceased. Such acts underscore the profound lack of respect afforded to enslaved and free Africans, whose dignity was denied not only in life but also in death, their final repose disturbed for illicit gain.

Perhaps one of the most gruesome episodes of desecration was the 1788 Doctor’s Riot, which swept through New York City. This violent uprising was precipitated by physicians who illegally stole corpses from graves, primarily from the African Burial Ground, to study them due to the severe shortage of medical cadavers. There was even speculation that the grounds were not only being looted but were becoming overcrowded due to the burial of unclaimed bodies in the place of the stolen remains, compounding the indignity suffered by the African-descendant community.

10. The Sacred Reinterment: Honoring the Ancestors

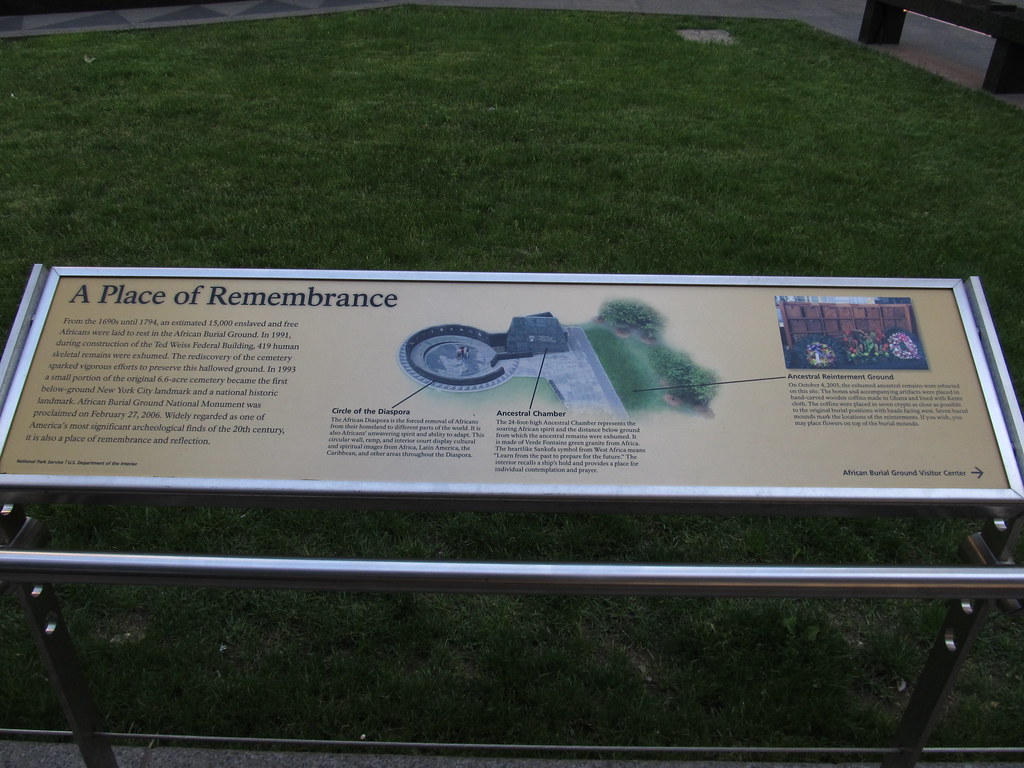

Following years of meticulous study and scientific analysis, a deeply moving and symbolically significant event took place: the reinterment of the 419 ancestors in the Ancestral Reinterment Grove on October 4, 2003. This ceremony, known as the “Rites of Ancestral Return,” was a powerful act of restorative justice, finally offering proper respect to those whose remains had been so long neglected and studied.

The reinterment was conducted with immense care and cultural sensitivity. The 419 skeletons were placed into hand-carved wooden coffins, specifically crafted in Ghana, and then reverently lined with Kente cloth, a vibrant symbol of West African heritage. These individual coffins were then placed into seven large sarcophagi, which were subsequently interred within seven burial mounds, with the ancestors’ heads facing west, in accordance with traditional spiritual beliefs.

This commemorative ceremony was broad in scope, designed to be inclusive and international, reflecting the vast diaspora represented by the burial ground. Organized by the GSA and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the emotional memorial journeyed across multiple cities—including Washington D.C., Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Newark—before culminating in Manhattan. Thousands of people attended the reinterment and commemoration, transforming a site of historical trauma into a place of profound healing and remembrance.

11. Designing a Place of Remembrance: The Memorial Competition

With the remains respectfully reinterred, the focus shifted to creating a permanent memorial that would honor the ancestors and educate future generations. The GSA launched a design competition for the site, recognizing the need for a structure that could adequately convey the profound historical and cultural significance of the African Burial Ground. This process involved extensive consultation with various stakeholders and community activists, ensuring diverse voices shaped the vision.

Over sixty proposals were submitted, reflecting the creative and passionate engagement of designers seeking to contribute to this important national landmark. Each proposal represented a unique interpretation of remembrance, history, and healing. The selection process was rigorous, aimed at finding a design that would resonate deeply with the site’s tragic yet triumphant narrative.

Ultimately, the winning memorial design was chosen in April 2005, a collaborative effort by Rodney Leon and Nicole Hollant-Denis. The cultural landscape architect for the memorial was Elizabeth Kennedy Landscape Architects. Their vision sought to translate the historical weight of the site into an evocative and enduring physical space, inviting reflection and learning for all who visit.

12. The African Burial Ground National Monument: A Symbol of Recognition

The completed memorial, a powerful architectural statement, consists of two main components: the Ancestral Chamber and the Circle of the Diaspora. The Ancestral Chamber stands an imposing 24 feet tall, a height deliberately chosen to represent the immense depth at which the graves were discovered, symbolizing the buried history now brought to light. It is crafted from Verde Fontaine green granite imported from Africa, and prominently features an engraved heart-shaped Sankofa symbol from West Africa, which carries the profound meaning: “Learn from the past to prepare for the future.”

The Circle of the Diaspora forms another integral part of the memorial, featuring a compelling map of the Atlantic area. This map serves as a stark reference to the Middle Passage, the brutal transatlantic voyage by which enslaved Africans were forcibly transported to North America. The Circle is constructed from stone sourced from both Africa and North America, a deliberate choice to symbolize the painful yet undeniable coming together of these two worlds through the history of slavery.

A particularly poignant element of the design is the “Door of Return,” which powerfully references “The Door of No Return”—the name given to the slave ports on the West African coast from which so many individuals were shipped, never to see their homeland again. The memorial is thus masterfully designed to facilitate a spiritual reconnection, linking ethnic African Americans to their ancestral origins and acknowledging a severed past.

On February 27, 2006, the site achieved its highest level of federal recognition when President George W. Bush signed a proclamation designating the burial site as the 123rd National Monument. This momentous decision officially transferred the Burial Ground to the operating jurisdiction of the National Park Service as its 390th unit. The federal government also committed $8 million for the memorial’s construction, underscoring the national significance of the site.

The completed memorial was dedicated on October 5, 2007, in a moving ceremony presided over by Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the revered poet Maya Angelou. As a further gesture of profound recognition and respect, the city officially renamed Elk Street, adjacent to the monument, as African Burial Ground Way, forever imprinting its historical importance into the urban landscape.

13. A Hub for Education: The Visitor Center’s Role

An essential component of the African Burial Ground National Monument’s mission to educate and enlighten opened its doors on February 27, 2010. The visitor center, strategically located within the Ted Weiss Federal Building at 290 Broadway—a structure built over a portion of the archaeological site—serves as a vital hub for interpretation and historical understanding. It provides a dedicated space where the public can engage with this complex and crucial history.

Inside, a permanent exhibit titled “Reclaiming Our History,” masterfully created by Amaze Design, takes visitors on an immersive journey. A particularly striking feature is a life-sized tableau by StudioEIS, powerfully depicting a dual funeral for both an adult and a child. This vivid portrayal immediately connects visitors to the human stories of those interred beneath their feet.

Beyond the emotional impact of the tableau, other parts of the exhibit delve deeply into the daily lives and contributions of Africans in early New York. It explores their integral connection to national history, demonstrating how their labor and resilience shaped the very foundations of the city and the nascent nation. Crucially, the exhibit also highlights the inspiring story of the late 20th-century community activism that led to the preservation of the burial ground, emphasizing the power of collective action.

To further enhance the educational experience, the visitor center includes a 40-person theater for presentations and films, along with a shop offering resources for deeper learning. The National Park Service actively manages the visitor center, orchestrating various cultural exhibitions and events throughout the year, ensuring a dynamic and ongoing engagement with the site’s rich heritage.

14. The Enduring Legacy: Reshaping American History

Beyond its physical presence as a national monument and a visitor center, the discoveries at the African Burial Ground have profoundly reshaped the popular understanding of early African-American history, not just in New York City, but across the entire nation. This site has become a catalyst for a necessary re-evaluation of historical narratives that had long overlooked or suppressed the contributions and suffering of enslaved peoples.

This shift in perspective is clearly evidenced by a surge in new scholarly works and publications dedicated to this topic. A remarkable example is the New-York Historical Society, which mounted its first-ever exhibit on slavery in New York in 2005. The overwhelming popularity of this exhibit led to its extended run into 2007, demonstrating a widespread public appetite for these previously untold stories.

The African Burial Ground has been instrumental in correcting historical inaccuracies, particularly the underestimation of New York City’s role in the institution of slavery. Popular understanding now acknowledges that, in the 18th century, enslaved individuals may have constituted as much as a quarter of the New York workforce, a proportion higher than that in Philadelphia and Boston combined, highlighting the pervasive nature of slavery in the North.

The journalist Edward Rothstein eloquently captured the significance of this site, noting that “Among the scars left by the heritage of slavery, one of the greatest is an absence: where are the memorials, cemeteries, architectural structures or sturdy sanctuaries that typically provide the ground for a people’s memory?” The African Burial Ground stands as a monumental answer to this question, filling a crucial void in America’s collective memory.

Furthermore, the long controversy and the ultimate preservation of the site have left an indelible mark on public archaeology. Government agencies and private developers have learned the critical importance of “include[ing] descendant communities in their salvage excavations, especially when human remains are concerned,” ensuring that future archaeological projects are conducted with greater sensitivity and ethical responsibility.

Read more about: The Sony Pictures Email Leak: Unveiling Internal Strife, Corporate Misconduct, and Hollywood’s Unseen Challenges

15. The Future of Preservation: Continuous Engagement and Respect

The journey of the African Burial Ground, from a forgotten colonial cemetery to a revered national monument, underscores the ongoing and vital need for continuous preservation and recognition. The very act of its rediscovery and the subsequent fight for its protection serve as a powerful testament to the resilience of history itself, refusing to remain buried.

Even years after its dedication, interest in the site’s future and its role in New York City’s landscape persists. For instance, in 2016, The Hoeg Corporation, an African-American owned development firm, alongside the monument’s architect Rodney Leon and Bizzi & Partners Development, tendered a significant offer to purchase and develop adjacent properties, demonstrating an ongoing engagement with the site’s presence within a modern urban context. Such proposals highlight the continuous balance required between urban development and the sacred imperative to protect and honor historical memory.

Ultimately, the African Burial Ground National Monument stands as an enduring beacon, a perpetual reminder of silenced histories and the lives of those who built this nation under duress. Its existence demands an ongoing commitment to education, respectful engagement, and the diligent protection of sacred spaces. For generations to come, it will ensure that the profound stories and contributions of enslaved and free Africans continue to be integrated into the broader American narrative, fostering a more complete and honest understanding of our shared past.

From the quiet, leaf-covered depressions of Newnan to the bustling heart of Lower Manhattan, these slave cemeteries are more than just archaeological finds; they are enduring echoes of human lives, of immense suffering, and of indomitable spirit. They challenge us to listen closely to the whispers of the earth, to confront the complexities of our history, and to build a future rooted in a profound and unwavering respect for all who came before us. Their stories, once buried, now rise to remind us that true enlightenment begins with acknowledging every chapter of our collective human story.