The art of acting stands as one of humanity’s most ancient and enduring forms of expression, a mirror reflecting societies, cultures, and the intricate tapestry of human experience across millennia. From the solitary figure stepping onto a rudimentary stage in ancient Greece to the celebrated luminaries of the 19th-century theatrical world, the journey of the actor has been one of constant evolution, marked by both profound respect and deep societal prejudice. This profession, rich in history and complex in its terminology, has navigated shifting social norms, technological advancements, and evolving artistic philosophies to become the multifaceted craft recognized today.

This in-depth exploration commences with the very language used to define those who inhabit fictional roles, delving into the historical nuances of terms like ‘actor,’ ‘actress,’ and ‘player.’ Following this foundational understanding, we will embark on a chronological journey through the foundational eras of Western theatre, examining its genesis in ancient Greece, its diverse forms in ancient Rome, and its often-perilous existence through the Middle Ages. We will then trace the dramatic shifts brought by the European Renaissance, including the emergence of professional troupes and the gradual, sometimes contentious, integration of women onto the stage, culminating in the transformative developments that reshaped the actor’s status and the industry itself by the 19th century.

1. **Defining the Performer: Terminology in the Acting Profession**

The word “actor,” while widely understood today, possesses a history of nuanced and at times contentious usage. Originally, the term existed for much of the English language’s history to signify “one who does something,” but it was not until the 16th century that it began to specifically refer to an individual performing in theatre. This evolution in language underscores the formalization and recognition of performance as a distinct professional endeavor, distinguishing it from broader actions or deeds.

One of the most notable terminological developments has been the introduction and subsequent debate surrounding the term “actress.” According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first recorded instance of “actress” appeared in 1608, attributed to Middleton. In the 19th century, this term carried a significant social stigma, as women in acting were frequently associated with courtesans and perceived promiscuity, reflecting deeply ingrained societal prejudices of the era. Despite these challenges, the 19th century also paradoxically witnessed the rise of the first female acting “stars,” such as the renowned Sarah Bernhardt, who transcended these societal limitations through their immense talent.

Following the English Restoration of 1660, when women were finally permitted to appear on stage in England, “actor” and “actress” were initially used interchangeably for female performers. However, under the influence of the French term “actrice,” “actress” eventually became the commonly accepted descriptor for women in both theatre and film. In modern times, particularly from the post-war period of the 1950s and ’60s, there has been a significant movement within the profession to re-adopt the gender-neutral term “actor.” This shift reflects a broader re-evaluation of women’s contributions to cultural life and a desire to dismantle gender-specific professional titles. For instance, The Observer and The Guardian’s 2010 joint style guide explicitly stated, “Use [‘actor’] for both male and female actors; do not use actress except when in name of award, e.g. Oscar for best actress,” aligning with perspectives such as Whoopi Goldberg’s assertion: “An actress can only play a woman. I’m an actor – I can play anything.” The UK performers’ union Equity, however, maintains that the subject still divides the profession, indicating a lack of universal consensus, even as major acting awards like the Academy Award for Best Actress continue to utilize the gender-specific nomenclature.

The term “player” also holds a historical place in the lexicon of performance. Within the context of United States cinema, “player” was a common gender-neutral term during the silent film era and the early days of the Motion Picture Production Code. However, in contemporary film discourse, it is generally considered archaic. Nevertheless, “player” has retained its relevance in theatre, often incorporated into the names of theatre groups or companies, such as the American Players or the East West Players. Additionally, actors engaged in improvisational theatre are frequently referred to as “players,” preserving this historical term within specific theatrical contexts.

2. **The Birth of Performance: Ancient Greek Theatre and Thespis’s Legacy**

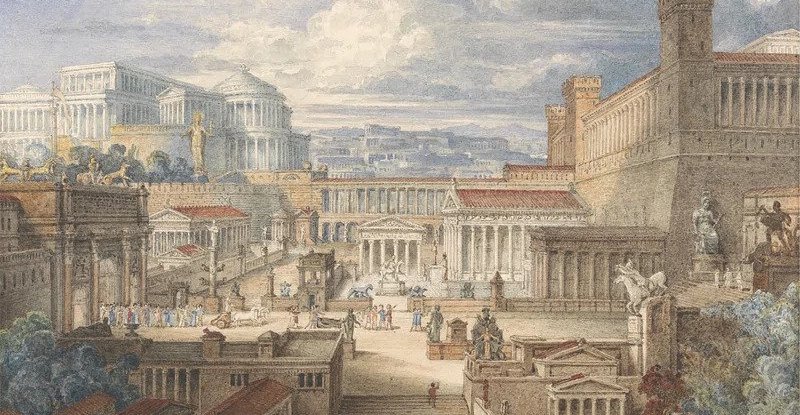

The origins of the actor, as we understand the role today, can be traced back to ancient Greece, a civilization renowned for its philosophical, artistic, and dramatic innovations. Before a pivotal moment in the 6th century BCE, Grecian stories were primarily conveyed through song, dance, and third-person narrative, lacking the direct portrayal of characters by individual performers. This traditional form of storytelling, while powerful, set the stage for a profound transformation in how narratives were brought to life.

The historical record points to 534 BC as the approximate year of a seminal event in theatrical history, marking the first recorded instance of a performing actor. It was then that Thespis, a Greek performer, stepped onto the stage at the Theatre Dionysus, becoming the first known individual to articulate words as a character within a play or story. This act of embodying a character, speaking in the first person, revolutionized narrative presentation and laid the foundational cornerstone for the art of acting. In honor of this pioneering figure, actors worldwide are still affectionately referred to as “Thespians.”

In the theatre of ancient Greece, the acting profession was exclusively male. These male actors were tasked with performing in three principal types of drama: tragedy, comedy, and the satyr play. This patriarchal structure of performance dictated that all female roles were also portrayed by men or boys, a convention that persisted for centuries in various cultures. The Greek model of dramatic performance, characterized by its distinct genres and all-male casts, established many of the conventions that would influence Western theatre for generations, demonstrating the initial restrictive yet impactful environment in which acting first flourished.

3. **Expanding Horizons: Ancient Roman Theatre and the Emergence of Female Performers**

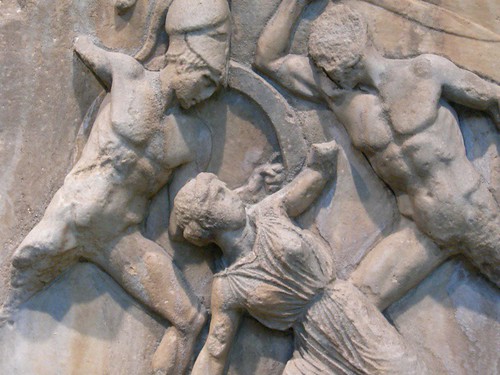

The theatrical traditions established in ancient Greece experienced significant development and expansion under the Romans, who adopted and adapted many Greek cultural forms. The theatre of ancient Rome evolved into a vibrant and diverse art form, encompassing a wide spectrum of performances. This ranged from the populist festival performances of street theatre, which often included dancing and acrobatics, to the more structured staging of situation comedies, and the verbally elaborate high-style tragedies that captivated elite audiences.

A notable divergence from Greek tradition was the allowance of female stage performers in ancient Rome. While the majority of these women were frequently employed in roles that emphasized dancing rather than speaking, a significant minority of actresses did attain speaking parts. These talented individuals not only performed in prominent roles but also achieved considerable wealth, fame, and recognition for their artistic contributions. Figures such as Eucharis, Dionysia, Galeria Copiola, and Fabia Arete stand out as examples of these early female stars, whose performances captivated Roman audiences.

Furthermore, these Roman actresses demonstrated a remarkable level of professional organization by forming their own acting guild, known as the Sociae Mimae. The existence of such a guild suggests a collective effort to support and advance their profession, and historical records indicate that this organization was evidently quite wealthy, signaling the economic viability and societal importance of female performers within Roman theatre. However, despite these early advancements, the profession of acting, including the role of the actress, appears to have largely diminished or died out in late antiquity as the Western Roman Empire declined.

4. **Navigating the Dark Ages: Theatre in the Medieval World**

Following the decline of the Western Roman Empire through the 4th and 5th centuries, Western Europe entered a period of widespread disorder, commonly known as the Early Middle Ages. During this tumultuous time, the structured theatrical traditions of antiquity largely faded, giving way to small, nomadic bands of actors. These performers traveled across Europe, staging simple, often crude scenes wherever they could gather an audience. Their performances, however, lacked the sophisticated dramatic structures and societal patronage that characterized earlier eras.

Traditionally, actors in the Early Middle Ages were not afforded high social status. Consequently, these traveling troupes were frequently viewed with deep suspicion and distrust. The Christian Church, a dominant cultural and moral authority during the Dark Ages, vehemently denounced actors, labeling them as dangerous, immoral, and pagan. This severe ecclesiastical condemnation led to harsh societal repercussions, including the denial of Christian burial in many parts of Europe, underscoring the precarious and marginalized existence of performers during this period.

Despite the pervasive societal and religious disapproval, theatre did not entirely disappear. By the Early Middle Ages, churches in Europe began to incorporate dramatized versions of biblical events into their liturgical practices. This liturgical drama gradually spread across the continent, from Russia to Scandinavia to Italy, by the middle of the 11th century. The Feast of Fools, a medieval festival, further encouraged the development of comedic elements within these performances. In the Late Middle Ages, vernacular Mystery plays, often incorporating comedy with actors portraying devils, villains, and clowns, were produced in numerous towns. The majority of these performers were drawn from the local population, serving as amateur participants, and in England, these amateur performers were exclusively male, although some other countries did see female participation, such as in the Bozen Passion Play in 1514, where women performed all the female parts.

Alongside religious drama, secular plays also emerged. Adam de la Halle’s “The Play of the Greenwood” in 1276 stands as the earliest recorded secular play, featuring satirical scenes and folk elements like faeries and supernatural occurrences. Farces also gained popularity after the 13th century, reflecting a growing taste for comedic and observational forms of entertainment. Towards the end of the Late Middle Ages, a significant shift occurred with the appearance of professional actors in England and Europe, marking a gradual transition from amateur, community-based performances to a more structured and specialized theatrical profession. Both Richard III and Henry VII, for instance, maintained small companies of professional actors, signaling the nascent return of sustained patronage for the craft.

5. **The Renaissance Stage: Italy’s Innovation and the Rise of Professional Troupes**

The Renaissance period in Europe marked a profound rebirth for the performing arts, building upon medieval traditions while introducing radical innovations that would shape theatre for centuries. A pivotal development was the emergence of the Commedia dell’arte troupes, which, beginning in the mid-16th century, performed lively improvisational playlets across Europe. This form of theatre was uniquely actor-centered, requiring minimal scenery and very few props, emphasizing the performers’ skill in spontaneous creation. Plays were essentially loose frameworks providing situations, complications, and outcomes, around which actors improvised using stock characters. A typical troupe comprised 13 to 14 members, with most actors compensated through a share of the play’s profits, roughly proportional to the size of their roles.

Renaissance theatre broadly drew from several medieval traditions, including mystery plays, morality plays, and the “university drama” which attempted to recreate Athenian tragedy. The Italian tradition of Commedia dell’arte, alongside the elaborate masques frequently presented at court, significantly contributed to the shaping of public theatre. Even before the reign of Elizabeth I, companies of players were formally attached to the households of leading aristocrats, performing seasonally in various locations. These aristocratic affiliations formed the crucial foundation for the professional players who would later grace the Elizabethan stage. However, the development of theatre faced a significant setback when Puritan opposition to the stage led to the banning of all plays within London, as Puritans viewed theatrical performances as immoral.

Critically, the Renaissance also witnessed the professional debut of women on stage in Europe, first in Italy, Spain, and France. The earliest known professional company with named members, from Padova in 1545, consisted entirely of men. However, by 1562, an unnamed actress from Rome was mentioned performing with “Moorish dances” in Mantova. Lucrezia Di Siena, whose name appears on an acting contract in Rome from October 10, 1564, is referred to as the first Italian actress known by name. Vincenza Armani and Barbara Flaminia are recognized as the first primadonnas and the first well-documented actresses in Italy and Europe. From the 1560s onward, actresses became the norm in Italian theatres, and Italian theatre companies touring abroad introduced women performers to many other countries.

Outside of Italy, women also began to appear on stage during the 16th century. In Spain, during the Spanish Golden Age theatre (1590–1641), women were an integral part of performances from the very beginning. Figures like Ana Muñoz, who toured and later managed her own company, Jerónima de Burgos, who toured Portugal and Spain, and Micaela de Luján, a role model for Lope de Vega, were active actresses during the 1590s. In France, professional actresses were reportedly active in the second half of the 16th century, though documentation of their names is less extensive than in Italy. Marie Vernier, also known as Mlle La Porte, stood out as the leading lady and co-director of Valleran-Lecomte’s theatre company, which performed in Paris and toured the Spanish Netherlands from at least 1604, demonstrating the growing prominence and professionalization of women in European theatre.

6. **From Restoration to Revered Profession: The 17th, 18th, and 19th Century Transformations**

Following the vibrant Renaissance, the art of theatre continued to expand across Europe, with countries developing their own native professional acting traditions and theatres throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. This era brought evolving attitudes toward women performing on stage, as each nation formed its own opinions and policies. Consequently, women actors gradually appeared in various countries, sometimes after explicit legal reforms, and at other times through a slower, informal process where individual theatre managers began to employ them. The timeline for this varied significantly across the continent.

In Germany and the Netherlands, women started performing in native traveling theatre companies by the mid-17th century. The initial actresses were typically the wives and daughters of theatre managers, whose presence was often accepted due to their familial supervision within the company. Ariana Nozeman, for example, made her debut in Amsterdam on April 19, 1655, in a leading role, becoming the first woman to do so in the Dutch Republic. Similarly, in September 1655, “female players” were noted in Frankfurt, Germany, for the first time. Catharina Elisabeth Velten notably acted with her mother and sister and later managed her husband’s theatre, maintaining a policy of employing women, thus establishing a lineage of female theatrical leadership.

England, however, was comparatively late in integrating women onto its stage. Throughout the first half of the 17th century, women were still prohibited from performing. English audiences were initially exposed to female actors through visiting foreign theatre companies, such as the Italian actress Angelica Martinelli in 1578. Yet, these rare occurrences did not immediately lead to reform, and no native English professional actresses existed. A striking incident in November 1629 saw a French theatre company’s actresses “hissed, booed and pippin-pelted from the stage” in London, highlighting the entrenched resistance. The lifting of an eighteen-year Puritan prohibition on drama after the English Restoration in 1660 finally allowed women to appear on stage. Margaret Hughes is often credited as the first professional actress on the English stage, with King Charles II’s enjoyment of watching actresses playing a role in this pivotal shift. Specifically, Charles II issued letters patent in 1662, granting theatrical monopolies that permitted actresses to perform for the first time.

Further east and north in Europe, the debut of women actors often came later, not due to outright bans, but because these regions developed national theatres with native professional actors at a later stage. Foreign actresses frequently performed decades before any native actors of either gender appeared. In Sweden, for example, there was no formal ban on women performing; Dutch theatre companies including women, such as Ariana Nozeman, Elisabeth de Baer, and Susanna van Lee, performed at the royal court in 1653. However, it was not until the inauguration of the Kungliga svenska skådeplatsen in 1737 that native Swedish actresses, including Beata Sabina Straas, were employed. Russia’s first theatre in Moscow (1672) initially employed foreign women actors, but a 1756 decree finally led to the recruitment and training of native Russian actors, including five pioneering women such as Avdotya Mikhailova and Elizaveta Zorina. Similarly, in Poland-Lithuania, the National Theatre in Warsaw, founded in 1765, included women like Antonina Prusinowska and Wiktoria Leszczyńska among its first native Polish actors. Greece, achieving independence in 1830, saw its first modern permanent theatre in 1840, with Maria Angeliki Tzivitza making her debut as the first Greek actress that year, followed by Ekaterina Panayotou in 1842, who is recognized as the first professional Greek actress with formal training, marking the gradual but definitive integration of women into the theatrical fabric across the continent.

By the 19th century, the negative perception of actors largely reversed, transforming acting into an honored, popular profession and art form. This significant shift was propelled by the rise of the actor as a celebrity, attracting audiences who flocked to see their favorite “stars.” A new model emerged with actor-managers, who formed their own companies, controlling actors, productions, and finances. Successful actor-managers, like the renowned British figure Henry Irving (1838–1905), built loyal clienteles and toured extensively, performing a repertoire of well-known plays, particularly Shakespearean works. Irving, famed for innovations such as dimming house lights to focus attention on the stage, demonstrated the immense power of star actors to draw enthusiastic audiences. His knighthood in 1895 symbolized the full acceptance of actors into the higher echelons of British society, cementing the profession’s newfound respectability and cultural significance.

7. **The 20th Century: Redefining the Industry and the Actor’s Role**

The dawn of the 20th century marked a significant inflection point for the acting profession, fundamentally altering its structure and operational dynamics. The economic realities of mounting large-scale productions rendered the traditional actor-manager model increasingly unsustainable. The sheer complexity and capital required to operate theatre companies, particularly in major urban centers, necessitated a shift away from individual artistic control towards more corporate-driven enterprises.

This era witnessed a distinct specialization within theatrical roles, with the emergence of dedicated stage managers and, subsequently, the vital figure of the theatre director. No longer was it feasible to find individuals who could seamlessly combine exceptional acting talent with the demanding responsibilities of management and finance. This division of labor allowed for greater efficiency and artistic focus, albeit at the cost of the all-encompassing control previously exercised by actor-managers.

Major cities, in particular, saw a surge in the popularity of long-running productions, especially musicals, which catered increasingly to burgeoning tourist audiences. This commercial imperative placed an even greater emphasis on the allure of “big name stars” to draw crowds and ensure profitability. Organizations like the Theatrical Syndicate, Edward Laurillard, and most notably The Shubert Organization, became instrumental in this new landscape, establishing chains of theatres and consolidating power within the industry, thereby reshaping the environment in which actors pursued their craft.

8. **Evolution of Craft: Diverse Acting Techniques**

The 20th century, alongside its industrial transformations, also saw a profound development in the theoretical and practical approaches to acting. One of the most influential philosophies, classical acting, emerged as a comprehensive approach integrating the expression of the body, voice, imagination, personalization, improvisation, external stimuli, and rigorous script analysis. This method draws upon the foundational theories of esteemed classical actors and directors, notably Konstantin Stanislavski and Michel Saint-Denis, providing a structured framework for performance.

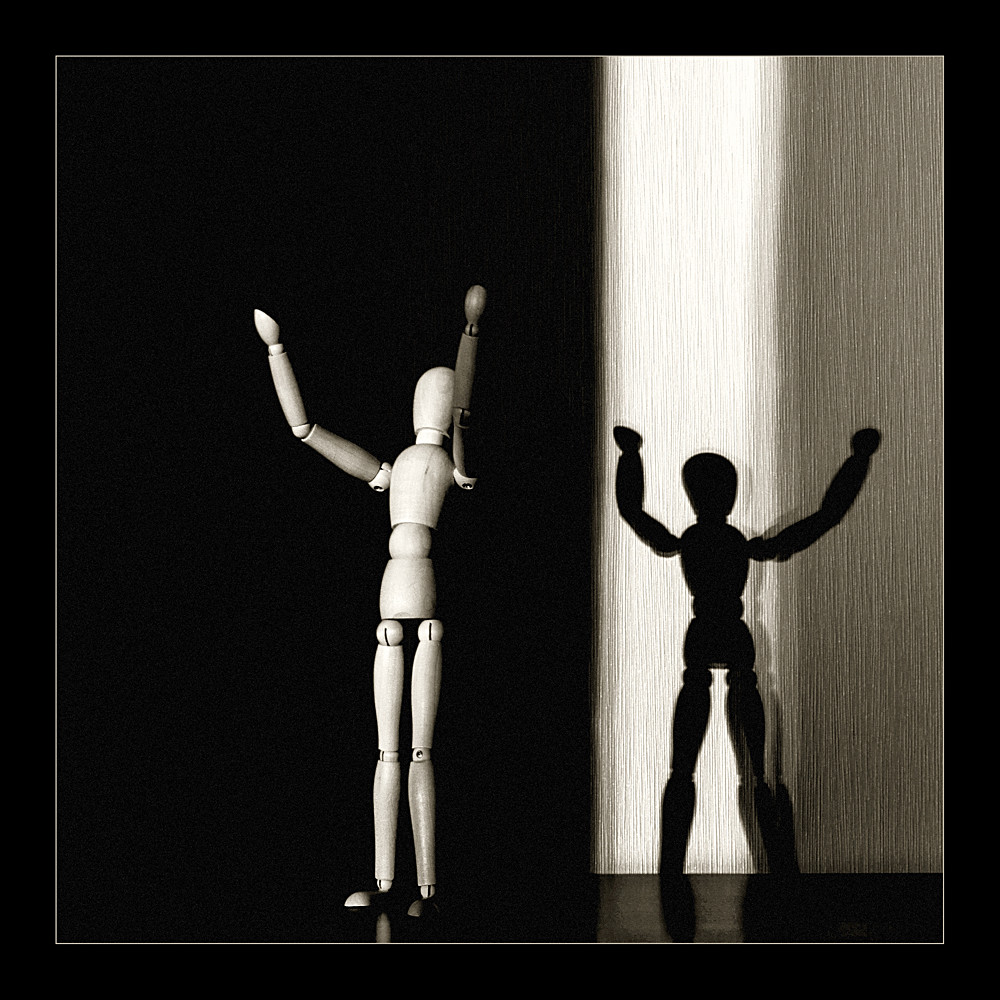

Stanislavski’s system, often referred to as Stanislavski’s method, stands as a cornerstone of modern actor training. It encourages actors to delve into their own personal feelings and experiences, utilizing these internal resources to truthfully convey the emotional and psychological realities of the character they portray. The essence of this technique lies in actors immersing themselves in the character’s mindset, actively seeking commonalities with their own lived experiences to achieve a portrayal that resonates with genuine authenticity.

Building upon aspects of Stanislavski’s work, method acting represents a distinct range of techniques formulated by Lee Strasberg. Strasberg’s method trains actors to achieve deeper characterizations by fostering an emotional and cognitive understanding of their roles, compelling them to identify personally with their characters through their own experiences. While profoundly influential, it is important to note that not all techniques derived from Stanislavski’s ideas are categorized as “method acting”; distinct approaches, such as those developed by Stella Adler and Sanford Meisner, offer their own unique pathways to performance excellence.

The Meisner technique, for instance, emphasizes the actor’s complete and unwavering focus on their scene partner, treating their interactions as if they are occurring in a real, immediate moment. This approach is rooted in the principle that authentic acting arises from an individual’s truthful response to other people and unfolding circumstances, thereby creating a more believable and compelling experience for the audience. Like many contemporary acting pedagogies, it is also fundamentally based on principles derived from Stanislavski’s comprehensive system.

Read more about: Beyond the Screen: 15 Stunt Realities Where Performers’ Fear Was Absolute, and AI’s Looming Impact

9. **Beyond Gender Norms: The Practice of Cross-Gender Acting**

Cross-gender acting, a practice where an actor portrays a character of the opposite , boasts a rich and varied history across theatrical and cinematic traditions. Historically, and notably in comedic theatre and film, dressing an actor as the opposite sex has been a long-standing device employed for humorous effect. William Shakespeare’s comedies, for example, frequently feature overt instances of cross-dressing, as seen with characters like Francis Flute in *A Midsummer Night’s Dream*, while films such as *A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum* and *Some Like It Hot* have famously utilized this trope for comedic impact.

Beyond simple comedic relief, certain actors have gained acclaim for their memorable portrayals of characters in drag, often forming the core of successful narratives. Dustin Hoffman’s transformative role in *Tootsie* and Robin Williams’s beloved performance in *Mrs. Doubtfire* are prime examples of this phenomenon, where the actor spends the majority of screen time convincingly disguised as a woman, driving both humor and poignant storytelling. These instances often explore themes of identity, perception, and societal roles.

More complex variations of cross-gender acting exist, where the layers of gender obfuscation become multifaceted. Julie Andrews’s performance in *Victor/Victoria*, where a woman portrays a woman pretending to be a man who then pretends to be a woman, exemplifies this intricate interplay. Similarly, Gwyneth Paltrow’s role in *Shakespeare in Love* involves a woman disguised as a man, adding depth to the narrative. In certain productions, such as *It’s Pat: The Movie* or the operatic character of Cherubino in *The Marriage of Figaro*, the ambiguity of a character’s gender, or the audience’s awareness of multiple levels of gender role-playing, creates rich dramatic and comedic territory.

While women playing male roles in film have historically been less common, several notable exceptions have garnered significant critical acclaim. Stina Ekblad’s portrayal of Ismael Retzinsky in *Fanny and Alexander* (1982) and Linda Hunt’s Academy Award-winning performance as Billy Kwan in *The Year of Living Dangerously* stand out. More recently, Cate Blanchett received an Academy Award nomination for her compelling depiction of Jude Quinn, a fictionalized Bob Dylan, in *I’m Not There* (2007), showcasing the increasing acceptance and artistic potential of women in traditionally male roles.

Modern theatre and film have also begun to embrace cross-gender casting to emphasize themes of gender fluidity, reflecting evolving societal understandings of identity. Iconic roles like Edna Turnblad in *Hairspray* have been notably played by men, including Divine in the original film and John Travolta in the 2007 musical. Similarly, performances such as Eddie Redmayne’s Oscar-nominated portrayal of Lili Elbe in *The Danish Girl* and Hilary Swank’s powerful depiction of Brandon Teena in *Boys Don’t Cry* illustrate the ongoing conversation around cisgender actors playing non-binary and transgender characters. Conversely, transgender actors, even prior to public transition, have also taken on cross-gender roles, further blurring traditional lines and enriching the tapestry of modern performance.

10. **Women on Stage and Screen: Global Perspectives and Modern Roles**

While Section 1 extensively detailed the historical struggle for women to appear on Western stages, the modern actor’s landscape presents a broader, more globally informed view of women’s evolving roles in performance. In many societies, women appearing on stage in public was long viewed as controversial and not respectable. Despite this, the journey from being barred or restricted to becoming central figures has been complex and varied, marked by significant cultural differences across the world.

In East Asian theatre, for example, unique conventions developed during periods when women were prohibited from performing. Japan’s Kabuki theatre, during the Edo period, famously introduced *onnagata*, male actors specializing in female roles, a tradition that persists to this day. Similarly, in certain forms of Chinese drama, such as Beijing opera, men traditionally performed all parts, including female characters. Conversely, in Shaoxing opera, women frequently take on all roles, including male ones, demonstrating a distinct reversal of gender-specific casting norms.

The Middle East also witnessed a profound transformation in the professionalization of women in acting. In the Ottoman Empire during the Tanzimat era, the modern theatre began in the 1850s, with Armenian theatre companies pioneering its development. Arousyak Papazian is recognized as the first female actor to perform onstage, making her debut in 1857. As conservative Muslim society did not initially deem acting a suitable profession for women, the earliest actresses were often Christian Armenians, and due to the severe stigma, they frequently received higher salaries than their male counterparts.

Similarly, in Egypt, the foundation of modern theatre in 1870 by Yaqub Sanu faced significant challenges in recruiting indigenous Egyptian actresses, as Muslim women were typically segregated and veiled. Sanu was compelled to employ non-Muslim women, leading to pioneering figures like the Dayan sisters and Miriam Samat, who became the first actresses in the Arab world. It was not until Mounira El Mahdeya in 1915 that the first Muslim actress graced the Egyptian stage, highlighting the slow but eventual integration of diverse women into these burgeoning theatrical traditions.

In contemporary Western theatre and film, women occasionally take on roles traditionally associated with boys or young men. The stage role of Peter Pan, for instance, is famously and traditionally played by a woman, as are most principal boys in British pantomime. Opera, too, has a long tradition of “breeches roles,” where mezzo-sopranos perform male characters like Hansel in *Hänsel und Gretel* or Cherubino in *The Marriage of Figaro*. This practice extends to presentations of older plays, such as Shakespearean works, where women frequently fill a large number of male characters in roles where gender is not crucial to the narrative, signifying a flexible and expansive approach to casting in the modern era.

Read more about: Seriously, Folks: If These 9 ’70s Horror Protagonists Showed Up Today, You’d Be Screaming at Your Screen (And Not Because of the Monsters!)

11. **The Economics of Performance: Compensation in Acting**

The financial landscape for actors has always been characterized by a wide breadth of potential incomes, a reality that has persisted across centuries. Historically, in 17th-century England, some actors could earn a comfortable living. William Shakespeare himself, during his early acting career, likely earned around 6 shillings per week, which was considered a typical wage for a skilled tradesman of that period, indicating a respectable, if not opulent, income for successful performers.

In contemporary times, the median hourly wage for actors in the United States, as of 2024, stands at $23.33 per hour. However, this median figure belies a significant challenge within the profession: many actors lack crucial benefits such as health insurance. Data from SAG-AFTRA, a prominent performers’ union, reveals that a mere 12.7% of its members earn sufficient income to qualify for its health plan, underscoring the precarious economic reality for a large segment of working actors.

Similarly, in Britain, full-time actors earned a median of £22,500 in the same year, a figure that falls slightly below the national minimum wage. These statistics highlight a professional environment where, despite the visibility of highly compensated stars, the vast majority of actors contend with modest incomes and often uncertain financial stability, challenging the perception of universal glamour associated with the profession.

Conversely, the upper echelons of the acting world present a starkly different financial picture, with certain individuals commanding exceedingly large incomes. Global film actors such as Aamir Khan and Sandra Bullock, for example, have been reported to earn tens of millions of dollars for single film productions, demonstrating the immense economic potential for those who reach the pinnacle of celebrity and demand in the industry. This disparity creates a bifurcated economic reality within the acting profession.

Special considerations also apply to child actors, particularly regarding their compensation. In the United States, union child actors are paid a daily rate of at least $1,204. However, due to their legal status as minors, most or all of this income is typically managed by their parents or legal guardians. To protect the earnings of young performers, laws like California’s Coogan Act mandate that 15% of a child’s income be deposited into a blocked trust account, accessible only upon reaching legal adulthood. States such as Illinois, New York, New Mexico, and Louisiana have implemented similar protective requirements, recognizing the unique vulnerabilities of child performers.

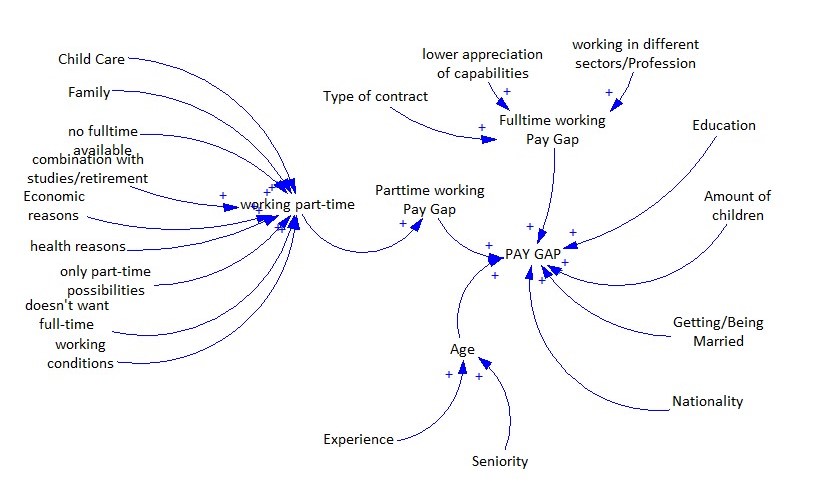

12. **Addressing Inequality: The Persistent Gender Pay Gap**

The issue of compensation within the acting profession is further complicated by a persistent and widely documented gender pay gap, highlighting a significant disparity in earnings between male and female performers. A 2015 report by Forbes underscored this imbalance, noting that only 21 of the 100 top-grossing films of 2014 featured a female lead or co-lead, while the overall representation of female characters in these films stood at a mere 28.1 percent. This underrepresentation at the top-tier of visibility directly correlates with earning potential.

In the United States, this disparity extends across all scales of salaries within the industry. On average, white women in acting earn approximately 78 cents for every dollar a white man makes. This gap widens considerably for women of color, with Hispanic women earning 56 cents, Black women 64 cents, and Native American women just 59 cents for every dollar earned by a white male actor. These figures reveal deeply entrenched systemic inequalities that intersect with both gender and race.

Forbes’s analysis of U.S. acting salaries in 2013 provided further quantitative evidence of this pervasive gap. The report determined that the men on Forbes’s list of top-paid actors for that year collectively earned two and a half times as much money as the top-paid actresses. This stark contrast illustrates that even among the highest-earning performers, a significant financial chasm exists, indicating that female actors, regardless of their celebrity status or box office draw, face systemic disadvantages in compensation.

The persistent gender pay gap in acting is not merely a matter of individual salaries but reflects broader industry practices, from casting decisions to negotiation dynamics. While significant strides have been made in recognizing and discussing this issue, the data continues to demonstrate a clear need for sustained efforts to achieve true equity in compensation and representation for women in all facets of the acting profession. Addressing these disparities is crucial for fostering a more inclusive and fair environment for all performers in the modern actor’s landscape.

As we reflect on the multifaceted journey of the actor, from the ancient Greek stage to the intricate landscape of contemporary media, it becomes clear that this profession is a living testament to human adaptability, artistry, and resilience. Actors, regardless of their era, have consistently held a mirror to society, challenging norms, shaping perceptions, and enriching our collective human experience. The ongoing evolution of techniques, the increasing embrace of diverse identities, and the critical discussions surrounding equity and representation all point towards a future where the art of acting continues to evolve, reflecting an ever-more complex and inclusive world. The stage, the screen, and indeed, the very definitions of performance, remain dynamic spaces, continually shaped by the dedicated individuals who step into character and bring stories to life.