In our relentless pursuit of understanding the world around us, and indeed, the very mechanics of our own thoughts, few ideas prove as fundamental and yet as elusive as the ‘concept.’ It’s the invisible architecture of our cognition, the bedrock upon which all more concrete principles, beliefs, and even our everyday musings are built. From the simplest recognition of a ‘tree’ to the most complex scientific theory, concepts are the essential units that allow us to organize, interpret, and make sense of existence. They are the silent engines driving our ability to learn, categorize, and infer, shaping every interaction we have with reality.

This crucial role has naturally made concepts a vibrant battleground for inquiry across a multitude of disciplines. Linguists dissect how language structures them, psychologists probe their mental mechanisms, and philosophers grapple with their very essence and existence. It’s a truly interdisciplinary endeavor, with cognitive science acting as a flagship for connecting these diverse threads. The ongoing debate about what concepts truly *are*—whether they reside solely within our minds as neural patterns or exist independently as abstract entities—speaks to the profound philosophical and scientific challenges they present.

Join us on an intellectual journey as we delve into 14 distinct facets of what a concept entails, peeling back the layers of abstraction to reveal the intricate workings of human thought. We’ll navigate through foundational definitions, explore the great ontological divide, and trace the evolution of understanding from ancient philosophy to cutting-edge cognitive science. Prepare to look at the building blocks of your own understanding with a fresh, deeper perspective.

1. **Defining the Concept: An Abstract Foundation**At its core, a concept is precisely what it sounds like: “an abstract idea that serves as a foundation for more concrete principles, thoughts, and beliefs.” This isn’t just a convenient label; it’s a vital cognitive tool. Concepts play an undeniably important role in every aspect of cognition, allowing us to generalize from specific instances and form higher-level thinking. Without them, our mental world would be a chaotic jumble of raw sensory input, devoid of structure or meaning.

Across linguistics, psychology, and philosophy, these disciplines intensely study the logical and psychological structure of concepts, and crucially, how they are assembled to form coherent thoughts and sentences. This interdisciplinary focus highlights the concept’s multifaceted nature, demonstrating its importance from the individual mind’s processing to the shared structures of communication. The ongoing quest to understand concepts has become a cornerstone of the emerging field of cognitive science.

Concepts themselves can be either exact or inexact, reflecting the precision with which we can define their boundaries. When the mind creates a generalization, such as the overarching concept of a tree, it performs an incredible feat: it extracts similarities from countless individual examples—a towering oak, a slender birch, a weeping willow. This powerful simplification process is what truly enables higher-level thinking, allowing us to move beyond individual specifics to broader categories. A concept, once formed, is then instantiated, or reified, by all of its actual or potential instances, whether these are tangible things in the real world or other abstract ideas.

Furthermore, concepts are regularly formalized in highly structured fields like mathematics, computer science, databases, and artificial intelligence, where they appear as classes, schema, or categories. This formalization underscores their utility as organizational principles. In everyday, informal use, however, the word ‘concept’ can simply refer to any idea, highlighting its pervasive yet often unexamined presence in our daily vocabulary. It’s vital to remember that a concept is merely a symbol, a representation of an abstraction; the word itself is not the thing it denotes. For example, the word “moon” (a concept) is not the actual celestial body but only represents it. Concepts are created to describe, explain, and capture reality as it is known and understood.

Read more about: Decoding the Universal Quartet: An In-Depth Journey Through the Enduring Significance of the Number Four Across Science, Culture, and History

2. **The Ontology Debate: Concepts as Mental Representations**A central and enduring question in the study of concepts revolves around their very ontology: what kind of things are they? Philosophers have traditionally parsed this query as a debate about their fundamental nature. The answer to this question profoundly influences other considerations, such as how concepts integrate into broader theories of the mind and what functions they can or cannot perform. Predominantly, two main views stand out in this ontological discussion: concepts as abstract objects, which we’ll explore next, and concepts as mental representations, which posits them as entities existing directly within the mind.

From a psychological perspective, particularly within the framework of the representational theory of mind, concepts are seen as structural building blocks. They serve as the foundational components of what are termed mental representations, which are colloquially understood as the ideas swirling within our minds. These mental representations, in turn, form the building blocks for propositional attitudes—our stances or perspectives towards ideas, such as “believing,” “doubting,” “wondering,” or “accepting.” This hierarchical analysis ultimately connects our common, everyday understanding of complex thoughts to the more scientific and philosophical understanding of fundamental concepts.

The physicalist view takes this a step further, asserting that in a physicalist theory of mind, a concept is fundamentally a mental representation. Under this interpretation, the brain actively uses these representations to denote a class of things in the external world. Crucially, a concept is literally conceived as “a symbol or group of symbols together made from the physical material of the brain.” This perspective grounds the abstract idea in tangible neurological reality. Concepts, in this sense, are a necessary subset of mental representations, enabling us to draw appropriate inferences about the diverse entities we encounter daily. Their utility is undeniable in core cognitive processes such as categorization, memory, decision making, learning, and inference.

Remarkably, concepts are thought to be primarily stored in long-term cortical memory, which stands in contrast to the episodic memory of particular objects and events. Episodic memories, representing specific experiences, are housed in the hippocampus. Evidence for this critical separation emerges from studies of patients with hippocampal damage, such as the well-known case of patient H.M. This abstraction of daily hippocampal events and objects into more stable cortical concepts is often considered to be a key computation underlying certain stages of sleep and dreaming. Indeed, many individuals, harking back to observations made by Aristotle, report dream memories that appear to blend the day’s occurrences with analogous or related historical concepts, suggesting an active process of sorting or organizing into more abstract conceptual frameworks during rest.

3. **Concepts as Abstract Objects: Beyond the Mind**Contrasting sharply with the view of concepts as mental representations, the semantic view suggests that concepts are, in fact, abstract objects. In this paradigm, concepts are considered to belong to a category entirely separate from the human mind itself, existing as independent entities rather than mere internal mental constructs. This perspective posits a realm of concepts that operates outside the confines of individual cognition, possessing an objective existence.

An ongoing debate surrounds the precise relationship between these abstract concepts and natural language. However, a crucial starting point for understanding this view is the clear philosophical distinction between a concept—for instance, the concept of “dog”—and the actual physical things in the world that are grouped by this concept, also known as its reference class or extension. The word ‘dog’ is not the furry, four-legged creature itself but rather a mental or abstract placeholder for its generalized characteristics. Concepts that can be neatly equated to a single word are specifically referred to as “lexical concepts,” highlighting their direct connection to our linguistic structures.

The detailed study of concepts and their underlying conceptual structure naturally spans across the disciplines of linguistics, philosophy, psychology, and cognitive science. This broad engagement underscores the foundational nature of concepts, as researchers from various fields attempt to unravel their true essence and impact on human understanding. The semantic view offers a compelling alternative to purely mentalistic interpretations, opening up pathways to explore concepts as part of a larger, independently existing intellectual framework.

Read more about: Unpacking the Building Blocks of Thought: An Accessible Deep Dive into the World of Concepts

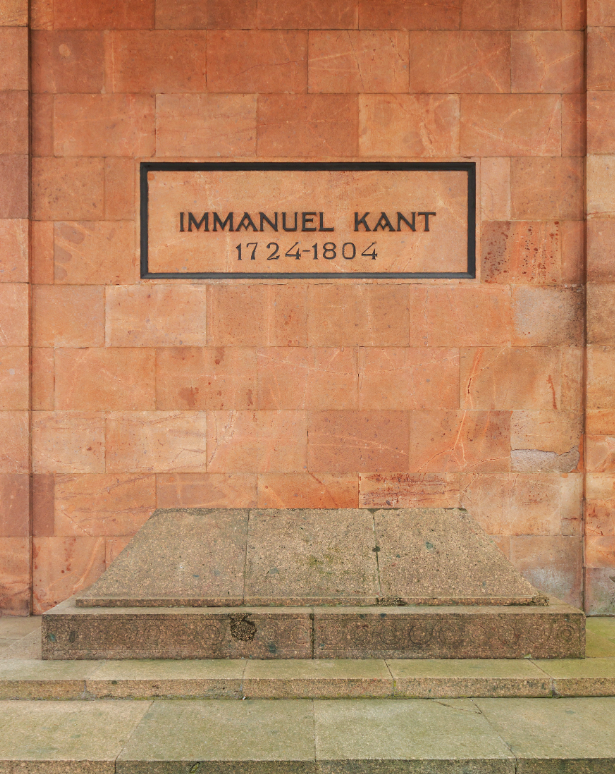

4. **Kant’s Categories: A Priori and A Posteriori Concepts**Immanuel Kant, a pivotal figure in philosophy, advanced a profound view on the origins and nature of human understanding, maintaining that our minds are equipped with more than just concepts derived from sensory experience. He posited that human minds possess not only empirical, or *a posteriori*, concepts, but also pure, or *a priori*, concepts. This distinction radically shifts how we consider the genesis of our foundational ideas, suggesting an intrinsic structure within the mind itself that shapes our perception of reality.

Unlike empirical concepts, which are abstracted directly from individual perceptions and experiences, Kant argued that *a priori* concepts originate solely “in the mind itself.” These innate mental structures are not learned but are inherent to our cognitive apparatus. He famously labeled these concepts ‘categories,’ using the term to denote predicates, attributes, characteristics, or qualities. However, these pure categories are not predicates of a particular, specific thing but rather predicates of things in general, universal frameworks through which we understand the phenomenal world. According to Kant, there are twelve such categories that collectively constitute our understanding of objects as they appear to us. To bridge the gap and explain how an *a priori* concept could relate to individual phenomena, much like an *a posteriori* concept does, Kant introduced the intricate technical concept of the schema.

Conversely, Kant acknowledged that the account of a concept as an abstraction of experience is indeed partly correct. He designated these concepts, which arise directly from or out of experience, as “*a posteriori* concepts.” An empirical, or *a posteriori*, concept is fundamentally “a general representation (Vorstellung) or non-specific thought of that which is common to several specific perceived objects.” These are the concepts we form by observing patterns and shared characteristics in the world around us, representing common features or characteristics among diverse instances.

Kant meticulously investigated the process by which these empirical *a posteriori* concepts are created, detailing the logical acts of the understanding involved. He identified three essential and general conditions for generating any concept whatever: comparison, reflection, and abstraction. These three logical operations are fundamental to how our minds construct generalized ideas from a multitude of sensory inputs, transforming raw data into meaningful categories. Each step plays a distinct role in refining our understanding.

To vividly illustrate this process, Kant provided a classic example: “For example, I see a fir, a willow, and a linden. In firstly comparing these objects, I notice that they are different from one another in respect of trunk, branches, leaves, and the like; further, however, I reflect only on what they have in common, the trunk, the branches, the leaves themselves, and abstract from their size, shape, and so forth; thus I gain a concept of a tree.” This methodical progression, moving from observing individual differences to identifying shared traits and finally abstracting away non-essential variations, perfectly encapsulates how our understanding moves from particular instances to universal concepts.

5. **Embodied Cognition: Concepts Rooted in Experience**In the realm of cognitive linguistics, a compelling theory known as embodied cognition offers a distinct perspective on the nature of abstract concepts. This view posits that, rather than being entirely disembodied mental constructs, abstract concepts are in fact “transformations of concrete concepts derived from embodied experience.” It suggests that our physical interactions with the world and our sensory-motor experiences form the fundamental basis even for our most abstract thoughts, grounding cognition in our physical existence.

The primary mechanism for this transformation is structural mapping, a process where properties from two or more ‘source domains’ are selectively projected or mapped onto a ‘blended space.’ This phenomenon is often referred to as conceptual blending, as detailed by Fauconnier & Turner. A common and highly illustrative class of these blends is metaphors, where we understand abstract ideas (like ‘love’ or ‘time’) in terms of more concrete, embodied experiences (like a ‘journey’ or a ‘resource’). This makes abstract reasoning not a separate, higher-level faculty, but an extension of our direct, physical engagement with reality.

This theory stands in stark contrast to earlier philosophical positions. It directly challenges the rationalist view, championed by figures like Plato, which held that concepts are perceptions (or recollections) of an independently existing world of ideas, by vehemently denying the existence of any such transcendent realm. Furthermore, it offers a nuanced alternative to the empiricist view, which suggests that concepts are merely abstract generalizations formed from individual experiences. The embodied cognition perspective argues that the contingent and bodily experience is not abstracted away entirely; rather, it is “preserved in a concept,” maintaining a vital connection to its sensory origins.

While this perspective aligns well with the principles of Jamesian pragmatism, which emphasizes the practical consequences and experiential basis of thought, the notion of the transformation of embodied concepts through structural mapping makes a particularly distinct and significant contribution to our understanding of concept formation. It provides a robust framework for how our most ethereal ideas can be deeply intertwined with the tangible reality of our physical bodies and their interactions with the environment, offering a unified account of mind and body in the genesis of thought.

Read more about: Unpacking the Building Blocks of Thought: An Accessible Deep Dive into the World of Concepts

6. **Platonic Realism: Universal Concepts as Transcendent Forms**Shifting our focus to an earlier, yet profoundly influential, philosophical perspective, Platonist views of the mind construe concepts as inherently “abstract objects.” Plato, the revered ancient Greek philosopher, remains the “starkest proponent of the realist thesis of universal concepts.” His philosophy fundamentally shaped Western thought and offers a compelling, albeit challenging, vision of how concepts exist and function, placing them in a realm far removed from everyday experience.

According to Plato’s intricate view, concepts, and indeed ideas in general, are not merely products of human thought or experience. Instead, they are considered to be “innate ideas that were instantiations of a transcendental world of pure forms that lay behind the veil of the physical world.” This means that the concept of ‘beauty,’ for example, is not derived from observing beautiful things but is an echo or reflection of an eternal, perfect Form of Beauty existing independently. In this grand ontological scheme, universals—the shared qualities or characteristics that allow us to group individual objects—were elegantly explained as these transcendent objects, existing in a higher reality.

This form of realism, with its deep roots in Plato’s broader ontological projects concerning the nature of being and reality, is not merely of historical interest. Its echoes and revivals persist in contemporary thought. A notable example is how the view that numbers are Platonic objects was “revived by Kurt Gödel as a result of certain puzzles that he took to arise from the phenomenological accounts.” This illustrates the enduring power of Platonic realism to offer solutions to profound philosophical dilemmas, even in fields as abstract as mathematics, by positing an independent, objective existence for universal concepts.

7. **Frege’s Sense and Reference: Concepts as Linguistic Grasping**Gottlob Frege, often hailed as the founder of the analytic tradition in philosophy, revolutionized our understanding of language with his renowned argument for its analysis in terms of ‘sense’ and ‘reference.’ This distinction provides a sophisticated framework for understanding how words and expressions connect to reality, and, significantly, how concepts are embedded within our linguistic structures and cognitive grasp of the world. Frege’s insights offer a powerful lens through which to examine the ontological status of concepts as they manifest through language.

For Frege, the ‘sense’ of an expression in language goes beyond its mere denotation; it actively “describes a certain state of affairs in the world, namely, the way that some object is presented.” It’s the mode of presentation, the particular angle or perspective through which we apprehend a given object or situation. For instance, ‘the morning star’ and ‘the evening star’ both refer to the planet Venus, but their distinct senses—the way they present Venus—are different, embodying different conceptual understandings.

Crucially, many commentators on Frege’s work “view the notion of sense as identical to the notion of concept.” If this interpretation holds, and given that Frege regarded senses as the linguistic representations of states of affairs in the world, it logically follows that we can understand concepts as fundamentally representing “the manner in which we grasp the world.” This perspective imbues concepts with an inherent structure linked to how we perceive and articulate reality through language. Accordingly, concepts, understood as senses, are not just mental events but possess a distinct and significant ontological status, contributing to the fabric of objective meaning and understanding that underlies our communication and thought.

8. **Concepts in Calculus: An Autonomous Abstraction**Moving from the foundational debates, we encounter a fascinating realm where concepts forge their own path, largely untethered from direct perception: calculus. As Carl Benjamin Boyer meticulously documented in ‘The History of the Calculus and its Conceptual Development,’ concepts within this advanced mathematical discipline operate on a distinctly different plane. They are not merely refined perceptions or abstractions of physical phenomena; rather, they are accepted primarily for their internal consistency and their immense utility within the mathematical system itself.

Indeed, the profound ideas behind the derivative and the integral, cornerstones of calculus, are not understood to literally refer to spatial or temporal perceptions of our external, experiential world. They don’t represent a visual flicker of change or a tangible accumulation of volume. Instead, their validity and power derive from their logical coherence and their ability to solve complex problems within a rigorously defined framework. There’s no mystical connection to quantities on the cusp of ‘nascence or evanescence’ – a departure from earlier, more intuitive interpretations.

What this signifies is a remarkable evolution in conceptual thought. The abstract concepts of calculus are now regarded as fundamentally autonomous, existing with a self-sufficient logical reality. While they undeniably originated from a process of abstracting qualities from perceptions – stripping away non-essential attributes until only the common, essential characteristics remained – their modern understanding emphasizes this independence. It’s a testament to the mind’s capacity to build intricate systems of thought that, once established, stand robustly on their own conceptual merits, driving innovation in engineering, physics, and beyond.

9. **The Classical Theory of Concepts: Definitional Structures**Our intellectual journey next brings us to the oldest and for centuries, most influential, theory regarding the very structure of concepts: the Classical Theory. Tracing its roots back to the analytical prowess of Aristotle, this perspective dominated philosophical and psychological thought until the seismic shifts of the 1970s. Its premise is elegantly straightforward: concepts possess a definitional structure, much like words in a dictionary.

Under this theory, an adequate definition for a concept is conceived as a precise list of features. These features are not arbitrary; they must meet stringent criteria to truly define the concept. Specifically, they must be both *necessary* and *jointly sufficient* for anything to be considered a member of the class covered by that concept. A necessary feature is one that every single member of the class *must* possess, without exception. A set of features is jointly sufficient if, by having all of them, an entity is *guaranteed* to be a member of that class. The classic example often cited is the concept of a ‘bachelor,’ which is defined by the features ‘unmarried’ and ‘man.’ An entity is a bachelor if, and only if, it is both unmarried and a man.

This all-or-nothing approach is further underscored by the classical theory’s adherence to the law of the excluded middle. This fundamental logical principle implies an absolute boundary: there are no partial members of a conceptual class. An entity either unequivocally possesses all the necessary and jointly sufficient features and is thus a full member, or it lacks even one, and is entirely excluded. There’s no middle ground, no ambiguity; you are either ‘in’ or ‘out’ of the category defined by the concept.

The enduring power of the classical theory stemmed from its intuitive appeal and its immense explanatory scope. It provided a clear framework for understanding how concepts might be acquired, how we use them to categorize the world, and how their inherent structure could be leveraged to determine their referent class. For a considerable period, ‘concept analysis’ – the rigorous pursuit of articulating these necessary and sufficient conditions for concept membership – stood as a cornerstone activity in philosophy, a testament to the classical view’s pervasive influence.

Read more about: Unpacking the Building Blocks of Thought: An Accessible Deep Dive into the World of Concepts

10. **Deconstructing the Classical View: Arguments Against**Despite its longevity and intuitive resonance, the classical theory of concepts ultimately faced significant challenges, prompting a fundamental re-evaluation of how our minds truly categorize and understand the world. The 20th century, particularly influenced by thinkers like Wittgenstein and Rosch, brought forth a series of compelling arguments that effectively dismantled the classical paradigm, paving the way for more nuanced theories.

A primary point of contention was the stark realization that, for many concepts, particularly those rooted in sensory experiences, universally agreed-upon, strict definitions simply don’t seem to exist. Furthermore, human cognition often grapples with cases of ignorance or error regarding conceptual boundaries. We might not know the complete definition of a concept, or our understanding of what a definition entails could be flawed. Philosopher W.V.O. Quine’s incisive argument against analyticity, articulated in ‘Two Dogmas of Empiricism,’ also served as a powerful philosophical weapon against the very notion of fixed, definitional concepts.

Perhaps the most impactful criticisms emerged from the observation of ‘fuzzy membership’ within categories. Contrary to the classical theory’s all-or-nothing dictum, real-world experience reveals numerous instances where it is vague whether an item clearly falls into or out of a particular referent class. This phenomenon of borderline members is simply irreconcilable with a theory demanding equal and full membership for every element. Researchers like J.A. Hampton, in studies where participants were asked to differentiate items within categories, found that objects were rarely deemed clear-cut members or non-members. Instead, there was significant disagreement, with items like ‘sinks’ being barely considered ‘kitchen utensils’ and ‘sponges’ barely ‘non-members.’ Such widespread borderline cases fundamentally undermine the idea of perfectly defined concepts.

The culmination of these challenges, particularly the discovery of ‘typicality effects’ by Eleanor Rosch, proved to be a pivotal moment. Rosch’s research demonstrated that people consistently rate some items within a category as more ‘typical’ or representative than others – an observation the classical theory was utterly incapable of explaining. These findings were not just anomalies; they were foundational insights that sparked the development of the prototype theory, ushering in a new era of understanding conceptual structure and highlighting that psychologically, we don’t seem to use concepts as strict definitions in our everyday cognition.

11. **Prototype Theory: Family Resemblances and Fuzzy Boundaries**Out of the challenges to the classical view emerged the Prototype Theory, a powerful alternative that revolutionized our understanding of how concepts are structured in the human mind. Key proponents like Ludwig Wittgenstein, Eleanor Rosch, Carolyn Mervis, Brent Berlin, Anglin, and Posner were instrumental in shaping this perspective, which posits that concepts specify properties that members of a class *tend* to possess, rather than *must* possess. It’s a far more flexible and empirically supported model of categorization.

Wittgenstein famously described the relationship between members of a class as akin to ‘family resemblances.’ Just as not every member of a family shares every single physical trait, members of a conceptual category don’t necessarily share a single, defining characteristic. This allows for remarkable flexibility; a dog, for instance, can still be recognized as a dog even if it has only three legs, lacking a ‘necessary’ feature that a classical definition might demand. This nuanced view finds robust support in psychological experimental evidence for ‘prototypicality effects,’ which consistently show how people rate objects within categories like ‘vegetable’ or ‘furniture’ as varying in their typicality.

These experiments reveal that our psychological categories are inherently ‘fuzzy,’ a stark contrast to the rigid boundaries of the classical theory. We readily and consistently judge an item’s membership in a category by comparing it not to a strict checklist of features, but to a ‘typical member’ – a central exemplar that embodies the maximum possible number of features for that category. If an item is similar enough to this prototype in the most relevant ways, it is cognitively admitted as a member of the class. Rosch’s work was particularly influential in demonstrating that categories are organized around these central exemplars, offering a robust explanatory framework for how our minds manage the complexities of real-world categorization. Neuroscientific research, as explained by Lech, Gunturkun, and Suchan, even points to multiple brain areas, including visual association areas, prefrontal cortex, basal ganglia, and the temporal lobe, being involved in this intricate categorization process.

The Prototype perspective stands as a vital alternative, allowing for the fuzzy boundaries and attribute-based characterizations that the all-or-nothing classical approach couldn’t accommodate. Cognitive linguist George Lakoff emphasized how experience and cognition are absolutely critical to the function of language, aligning with this view. William Labov’s insightful experiment further illustrated this, showing that the *function* an artifact serves profoundly influences its categorization; a container holding mashed potatoes was deemed a ‘bowl,’ while one holding tea was a ‘cup,’ even with identical shapes. This experiment not only highlighted the role of context but also helped to illuminate the ‘optimal dimensions’ that define a prototype, like that of a ‘cup.’

This theory also directly confronts the classical view’s inherent contradiction when confronted with questions like ‘to what extent does something belong to a category?’ Such inquiries are nonsensical from a classical standpoint, where membership is absolute. However, prototype theory readily accounts for these gradations, mirroring similar complexities found in other linguistic fields. While Aristotelian categories might still serve some specific, well-defined cases, prototype theory offers a far more comprehensive and psychologically realistic account for the majority of our conceptual understanding.

Read more about: Unpacking the Building Blocks of Thought: An Accessible Deep Dive into the World of Concepts

12. **Theory-Theory: Concepts as Scientific Hypotheses**Evolving beyond the limitations of both classical and prototype theories, ‘Theory-theory’ emerges as another significant perspective on conceptual structure, offering a deeper understanding of how we categorize. This theory postulates that our categorization by concepts isn’t simply about listing features or comparing to a prototype; it’s more akin to the dynamic, explanatory process of scientific theorizing. Concepts, in this view, are not learned in isolation but are intricately woven into our broader mental ‘theories’ about the world.

Essentially, the structure of a concept within theory-theory is deeply reliant on its relationships to other concepts, all mandated by a particular mental theory or understanding we hold about how the world operates. This means our conceptual knowledge isn’t a static inventory but a constantly evolving web of interconnected ideas, much like a scientist’s evolving model of the universe. While its exact mechanisms may be less immediately intuitive than the previous two theories, its explanatory power for complex cognitive phenomena makes it a prominent and influential model.

One of theory-theory’s key strengths lies in its ability to address issues of ignorance and error that posed challenges for both classical and prototype theories. Consider the historical misconception of a ‘whale’ as a ‘fish.’ This error, from a theory-theory perspective, didn’t arise from a lack of defining features or an incorrect prototype, but from an underlying, albeit incorrect, ‘theory’ about what constitutes a fish and how a whale fits into that framework. When we learn that a whale is a mammal, we’re not just adding a feature; we’re fundamentally revising our mental theory, recognizing that whales don’t fit the previous explanatory structure we had for fish.

Theory-theory further postulates that people’s individual ‘theories’ about the world are what fundamentally inform their conceptual knowledge. Therefore, by analyzing these underlying mental explanations – which are personal, individual understandings rather than scientific facts – we can gain profound insights into how people structure their concepts. This perspective critically examines classical and prototype theories for relying too heavily on similarities as sufficient constraints. It suggests that the ‘cohesiveness’ of a category is more powerfully shaped by what ‘makes sense’ to the perceiver within their mental framework, rather than merely weighted similarities, which Tversky’s research has shown to fluctuate significantly depending on context and task. In this light, observed similarities between category members might often be collateral effects, rather than the primary causal drivers of categorization.

13. **Modern Conceptualization Methodologies: Bridging Rigor and Fluidity**In the dynamic landscape of the social sciences, the ‘conceptualization methodology’ has become a crucial battleground, seeking to refine how researchers define and utilize concepts. Traditionally, an approach heavily influenced by Giovanni Sartori treated concepts as precise, almost immutable categories, each endowed with clearly defined attributes. This conventional method often employed a ‘ladder of abstraction’ to systematically adjust a concept’s generality, ensuring clarity, logical consistency, and rigorous classification for analytical purposes. It was about creating clean, unambiguous intellectual containers.

In stark contrast, interpretive approaches to conceptualization emerged, viewing concepts as far more fluid and dynamic entities. These perspectives emphasize that concepts are products deeply embedded in language and shaped by specific social contexts, rather than existing as static, universal definitions. Researchers employing these methods focus keenly on analyzing how language itself, along with the researcher’s own positionality and perspective, actively shapes the meaning and interpretation of concepts in practical application. It’s a recognition of the inherent subjectivity and situatedness of understanding.

The ongoing methodological debates in the social sciences often center on how researchers can effectively refine concepts when they appear to be misaligned with empirical reality. Recognizing the strengths and limitations of both the conventional and interpretive traditions, emerging methodologies have sought to bridge this divide. A notable example is the structured four-step process developed by Knott and Alejandro, designed to guide researchers through the complex task of ‘reconceptualization’ when existing concepts no longer adequately capture observed phenomena.

Their innovative approach masterfully integrates the conventional need for conceptual clarity and analytical rigor with a crucial, reflexive attention to context. This synthesis aims to endow concepts with greater analytical leverage, allowing them to better illuminate and explain the complexities of the empirical world. The process meticulously involves mapping the attributes of an original concept against the subtle nuances and specificities of an empirical case. Through this detailed comparison, researchers can pinpoint precise misalignments, systematically deconstruct the old framework, and meticulously build a revised concept that is both robust and contextually sensitive.

14. **Ideasthesia: Sensing Concepts and the Hard Problem**Our final stop on this exploration of concepts brings us to a cutting-edge theory that proposes a profound connection between abstract ideas and phenomenal experience: ‘Ideasthesia,’ or the “sensing of concepts.” This theory suggests that the very activation of a concept within our minds may be the primary mechanism responsible for generating our conscious, phenomenal experiences. It posits a direct link between the abstract world of ideas and the vivid, subjective qualities of our perceptions, making it a pivotal area of inquiry for understanding consciousness itself.

Indeed, ideasthesia research positions the understanding of how the brain processes concepts as central to solving one of the most enduring mysteries in philosophy and neuroscience: the ‘hard problem of consciousness.’ This famously difficult problem seeks to explain how and why conscious experiences, or ‘qualia’—such as the subjective ‘sourness’ of a lemon’s taste, the ‘redness’ of red, or the ‘painfulness’ of pain—emerge from a physical system like the brain. If concept activation directly underpins these experiences, then unraveling concept processing could unlock the secrets of subjective awareness.

The theory of ideasthesia initially emerged from in-depth research into ‘synesthesia,’ a fascinating neurological phenomenon where stimulation of one sensory or cognitive pathway leads to automatic, involuntary experiences in a second sensory or cognitive pathway (e.g., seeing colors when hearing music). Crucially, researchers observed that a synesthetic experience first requires the activation of a ‘concept’ of the inducer. This insight suggested that the phenomenon wasn’t just about sensory crosstalk, but about the conceptual layer underlying perception. Later research has further expanded these initial findings, demonstrating that conceptual activation plays a significant role even in our everyday perception and conscious experience, extending beyond the unique cases of synesthesia.

This burgeoning field continues to prompt extensive discussion on the most effective theories of concepts. Alongside ideasthesia, other prominent theories, such as ‘semantic pointers,’ are also being explored. Semantic pointers propose that concepts are represented as complex symbols that integrate perceptual and motor representations, effectively binding different modalities of experience into a unified conceptual entity. These ongoing investigations underscore the vibrant, interdisciplinary nature of concept research, constantly pushing the boundaries of our understanding of mind, language, and reality.

From the ancient philosophical inquiries into innate forms to cutting-edge neuroscientific models of ideasthesia, the journey to understand concepts has been a relentless pursuit of clarity. It reveals that these seemingly invisible architectures of our minds are not just static definitions but dynamic, evolving structures that constantly shape how we perceive, interpret, and interact with the world. As we continue to unravel their intricate workings, we gain not only a deeper appreciation for the mechanics of human thought but also a more profound insight into the very essence of what it means to understand.