For many of us, Disney films aren’t just movies; they’re cherished cornerstones of childhood, the very fabric of our earliest dreams and adventures. We’ve watched them hundreds of times, sung along to every anthem, and perhaps even quoted them incessantly. These cinematic treasures, from the groundbreaking animations of the Golden Age to the vibrant stories of the Renaissance, have instilled values, sparked imagination, and offered an escape into worlds where magic is real and happy endings are guaranteed. They’ve shaped generations, weaving themselves inextricably into our cultural consciousness.

Yet, as we grow older and inevitably revisit these beloved tales with a more critical, adult eye, something rather curious begins to happen. The rose-tinted glasses of nostalgia start to slip, revealing tiny cracks in the otherwise flawless facade. Suddenly, we’re not just captivated by the enchanting stories; we’re left scratching our heads at some truly massive plot holes, those nagging inconsistencies that make absolutely zero sense. These aren’t just nitpicks; these are moments that, once noticed, become impossible to unsee, prompting a collective, “huh, now that you mention it…” from viewers around the globe.

So, prepare yourselves for a journey beyond the singing teacups and glass slippers. We’re about to dive deep into the heart of these narrative paradoxes, exploring the delightful absurdities and frustrating logical leaps that have bothered discerning viewers for years. We’ll dissect character motivations, scrutinize world-building choices, and ask the tough questions that Disney perhaps hoped we wouldn’t. Your favorite films may never look quite the same again, and believe us when we say, you’ve been warned.

1. **Cinderella’s One-of-a-Kind Shoe Size**Ah, the glass slipper. It’s the ultimate symbol of fairy tale magic, a beacon of hope, and the sole (pun intended) device used by Prince Charming to locate his true love. Cinderella, in her desperate flight from the ball, leaves behind this singular, exquisite slipper, leading to the kingdom-wide search for the mysterious maiden it perfectly fits. It’s a beautifully romantic premise, but let’s be real for a moment: as an adult, this whole scenario quickly falls apart under the slightest scrutiny.

We get it—the slipper is beautiful, wonderful, unique, magical, super special, etc. But what isn’t super unique? Cinderella’s actual foot. Cinderella was a human with human feet, right? So, when the Prince decides to find her simply by placing her shoe on all of the eligible ladies in the kingdom, you have to wonder: couldn’t that shoe have fit like a hundred girls? It beggars belief that in an entire kingdom teeming with women, only one single person possesses the exact foot size and shape to fit this glass slipper.

Is Cinderella, like, a size 4 adult or something super rare? Does she have extra toes? What shoe size is she that she’s literally the ONLY maiden in all the land that this shoe will fit? Perhaps we’re meant to assume the shoe was magical and would kind of adjust its size to only fit her, but if it was such a perfect, magically adjusting fit, why did it fall off in the first place? And while we’re asking, why search for the person the shoe fits, instead of just looking for the person who has the *other* shoe? That seems like a much more reliable way to make sure you’ve got the right girl. It’s a plot hole that, once noticed, makes the entire royal decree seem laughably inefficient.

Read more about: My Florida Life: Seven Years, Endless Surprises, and the Unforgettable Experiences That Changed Everything

2. **Ariel, Why Didn’t You Just WRITE Something to Prince Eric?!**Okay, this one honestly frustrates many viewers to no end, and it’s a prime example of a glaring logical leap. In *The Little Mermaid*, Ariel makes the ultimate sacrifice: she gives up her beautiful singing voice to Ursula in exchange for legs and three days on land to win Prince Eric’s love. The catch, of course, is that she can’t speak, leading to all sorts of comical misunderstandings and near-misses. But wait a minute, the movie itself gives us the definitive proof that this problem could have been solved with a quill and some parchment.

We explicitly see Ariel sign her name on the contract that Ursula provides her. And let’s be clear: it’s not a messy scrawl. It’s beautiful handwriting! Like, this girl got an A+ in cursive in second grade-type writing. If Ariel does indeed know how to write—and the evidence is literally inked on a magical scroll—then why in the name of Triton’s trident didn’t she just find some paper and write a note to Eric to explain what was going on? She could have even scrawled it in the sand! The lack of this seemingly obvious solution has puzzled audiences for decades.

Is it possible that Ariel only knows how to sign her name? Or perhaps it’s different to write underwater versus on land? Did Ursula not only take away her voice but also her ability to communicate in any other meaningful way? The film certainly doesn’t offer a clear explanation, forcing us to concoct our own far-fetched theories. Honestly, the movie would have been *real* short if she handed Eric a Post-it like, “I’m the girl you’re trying to find. Kiss me and I can talk. Love and kisses, Ariel. P.S., I’m actually half fish. The kiss will take care of it. We’ll talk about it later.” What a world that would have been.

3. **Buzz Knows He’s a Toy?***Toy Story* introduced us to one of cinema’s most iconic identity crises: Buzz Lightyear. When he first bursts onto the scene, Buzz is utterly convinced he is a true space ranger, an interstellar hero with a critical mission, not a plastic plaything in a kid’s bedroom. This fundamental misunderstanding of his own nature is the central comedic and dramatic tension of the first film, encapsulated perfectly by Woody’s exasperated cry, “YOU! ARE! A! TOY!”

So, with Buzz’s unwavering belief that he is a real space ranger, an actual living being from outer space, why then does he freeze like a statue when a human walks into the room, just like all the other toys? He truly seems to think the other toys are aliens on the planet where he’s crash-landed, so why mimic their seemingly bizarre, inanimate behavior? It just doesn’t compute. If he genuinely believed he wasn’t a toy, wouldn’t he continue his mission, or at least attempt to communicate with the “giant kid” named Andy?

We’ve seen theories attempting to explain this away, suggesting he’s trying to blend in with the “native” toys as a survival mechanism, in true Space Ranger fashion. Or perhaps he simply blacks out and has no control over it when a child is near. But given his conscious attempts to fly, fix his “broken” communicator, and escape to his home planet, his deliberate freezing is a stark contradiction. It’s so easy to miss as a kid, but as adults, we literally won’t be able to watch the movie the same way again, curiously watching for every time Buzz freezes, despite his conviction that he isn’t one. The film conveniently overlooks this inconsistency for the sake of its core premise, but for the discerning viewer, it’s a puzzling paradox.

4. **Where Did Chip’s Siblings Go?***Beauty and the Beast* is filled with enchanted household objects, each a former human servant trapped by the Beast’s curse. Among these delightful characters is Chip, the adorable teacup son of Mrs. Potts. He’s a lively, curious little fellow, always eager for adventure. However, a throwaway line and a fleeting visual detail introduce a peculiar plot hole that begs a much deeper, and slightly unsettling, question about the fate of the castle’s animated crockery.

At one point in the film, Mrs. Potts tells her son, Chip, to get in the cupboard with his brothers and sisters. Yeah, those other teacups you see back there? Apparently, they’re Chip’s siblings! We see several other teacups clustered around, implying a larger family unit. Yet, when the curse is finally broken at the end of the film, and all the enchanted objects transform back into their human selves, we *only* see Chip reunited with Mrs. Potts in human form. The other teacups, presumably his siblings, are conspicuously absent from this joyous family reunion.

What happened to them? Did Mrs. Potts not mean that they were her *literal* children, and perhaps just meant it metaphorically, referring to the other small teacups as if they were all her charges? Are they stuck as teacups forever, doomed to a life of inanimate servitude? Or is Chip simply the favorite kid, leaving us to imagine Mrs. Potts massively neglecting her other half-dozen children, keeping them locked in a dark closet for ten years? It’s a slightly disturbing thought. This little detail, easily overlooked, casts a long shadow over the supposedly happy ending, leaving us with far more questions about magical family dynamics than we ever anticipated.

5. **Why Didn’t Scar Just Kill Simba Himself?**Scar, the malevolent younger brother of Mufasa and the primary antagonist of *The Lion King*, is a villain of cunning, ambition, and ruthless efficiency—at least, when it comes to orchestrating the death of his king. Yet, immediately after Mufasa’s tragic demise in the stampede, Scar makes a monumental strategic blunder that could have been easily avoided, a plot hole that undermines his otherwise calculated evil.

Instead of finishing off young Simba himself and securing his rise to the throne beyond any shadow of a doubt, Scar leaves the crucial task of killing his nephew to the hyenas. And he knows, deep down, that his hyena companions aren’t always the *best* tools for critical assignments; he even sings a whole song basically making fun of them, noting their “vacant expressions” and implying that the “lights aren’t all on upstairs.” Given this assessment, why on earth would he entrust such a vital, empire-securing act to his bumbling, inept minions?

He could have killed Simba so quickly, so quietly, and so *certainly*, ensuring no loose ends. The guy already killed Mufasa without so much as shedding a tear, so clearly, the whole “murder” thing isn’t exactly weighing on his soul. Seriously, the movie could have been over after that. This decision, seemingly driven by Scar’s arrogance or perhaps a bizarre aversion to getting his own paws dirty in the final kill, creates an unnecessary risk that ultimately leads to his downfall. It’s a classic villain oversight, a hubris-fueled delegation that leaves us wondering if Scar, for all his intelligence, wasn’t quite as clever as he thought.

6. **Seriously, Move Further Away, Mother Gothel**In *Tangled*, Mother Gothel’s entire villainous plan hinges on keeping Rapunzel hidden away in a remote tower, completely isolated from the outside world and, crucially, from her royal parents who are desperate to find their missing daughter. The annual floating lanterns released by the king and queen on Rapunzel’s birthday serve as a poignant symbol of their enduring hope. These lanterns, which Rapunzel watches with fascination each year, become the ultimate catalyst for her desire to leave the tower and embark on her grand adventure, ultimately leading to Gothel’s demise and Rapunzel’s freedom.

But here’s the colossal, glaring plot hole: why did Mother Gothel choose a tower that was close enough to the Kingdom of Corona for Rapunzel to clearly see the lanterns every single year? Surely there are countless other, truly isolated places in the world where they could live, places far enough away that Rapunzel wouldn’t be able to see the lights or even know about them. If Mother Gothel is *so* dedicated to staying young forever and hiding Rapunzel away, why not *really* live in a place where the lanterns and the Kingdom of Corona would never be a concern? Why not head across a sea, or somewhere else far, far away? We even know Corona is in the same world as Arendelle, so options abound.

This decision isn’t just poor planning; it’s practically an open invitation for Rapunzel to discover her true heritage. Did Gothel think that perhaps if she moved Rapunzel too far away from where the magical flower was found, something would go wrong with her powers? The movie doesn’t offer a satisfactory explanation, leaving us to conclude that for all her deviousness, Mother Gothel had a curious blind spot when it came to real estate. And on a related note, how did she even build that tower? Did she hire forest freelance construction guys to shadily construct her kidnap tower, or is she actually a secret master craftswoman? Towers like that take *money* to build. Where was Mother Gothel getting all that scratch? These are the kinds of questions that keep us up at night.

Expanding our analytical lens, we now delve into the broader implications of Disney’s narrative choices, moving beyond individual character quirks to systemic world-building issues and deeper contradictions that ripple through these cinematic universes. This section uncovers six more profound plot holes, questioning the fabric of reality these films present and inviting us to ponder the often-overlooked absurdities that shape our favorite stories. From puzzling timelines to baffling economic models, prepare to have your understanding of Disney worlds fundamentally challenged.

Read more about: Mind-Blown! Things Only Adults Truly Notice When Rewatching Your Favorite Disney Princess Movies

7. **The Beast Looks Awfully Old To Be An Eleven-Year-Old**One of the most heartwarming transformations in Disney history occurs at the end of *Beauty and the Beast*, when the cursed Beast reverts to his human form, revealing a handsome prince. The film establishes that the curse has been in effect for ten years, meaning the Prince must find true love by his twenty-first birthday, or remain a beast forever. This timeline is crucial, but it introduces a rather glaring visual inconsistency that once you spot it, is impossible to ignore.

Consider the Prince’s self-portrait that Belle discovers in the castle; it depicts him as a young man, certainly in his late teens or early twenties, exuding an air of arrogance. If the curse has been active for a decade, and he must find love by twenty-one, a quick bit of math tells us that he would have been at most eleven years old when he was originally cursed and, by extension, when that portrait was painted. An eleven-year-old, no matter how precocious or self-absorbed, simply does not look like the strapping young man in that painting.

This isn’t a mere artistic flourish; it’s a significant visual anachronism that throws the entire narrative timeline into question. Are we to believe the Beast commissioned a portrait of his future self? Or that the curse magically fast-forwarded his physical maturity without aging him? It undermines the specific stakes of his impending 21st birthday, making the ten-year duration of his enchantment feel less concrete. The film, it seems, wanted the dramatic impact of a prolonged curse without fully committing to the visual logic of its timeframe.

What’s more, envisioning an arrogant, selfish eleven-year-old being the target of such a severe curse by an enchantress further complicates matters. It paints a picture of a magic user with questionable judgment, punishing a mere child with a fate typically reserved for more mature, knowingly cruel individuals. This detail forces us to reconsider the entire backstory, shifting the focus from a lesson learned by a vain adult to a seemingly disproportionate punishment inflicted upon a pre-teen.

8. **Why Don’t the Villagers Know About the Beast?**The cursed castle of the Beast, a sprawling, Gothic edifice, sits remarkably close to Belle’s “poor provincial town.” Despite its imposing size and the fact that its previous residents were human beings, the local villagers seem utterly oblivious to its existence or, at the very least, its transformation. When Maurice, Belle’s father, stumbles upon it and reports a fearsome Beast, he’s dismissed as a lunatic, his claims met with derision.

This widespread ignorance stretches credulity. How could a massive, presumably historically significant castle, and its entire court (including their monarch, the Prince), simply vanish from public consciousness for ten years? Did an enchantress’s spell not only transform its inhabitants but also wipe the collective memory of an entire village? The narrative doesn’t offer such an explanation, leaving a gaping hole in its world-building.

The villagers’ reaction, particularly their shock when Belle later confirms the Beast’s existence, makes this plot hole even more pronounced. It implies a total societal amnesia that is never justified. Furthermore, Gaston, the town’s arrogant antagonist, somehow knows exactly how to find the castle when he leads the mob, a convenient piece of knowledge that contradicts the general ignorance of the other townspeople.

This oversight isn’t just a minor detail; it impacts the very premise of Belle’s isolation and the Beast’s secret. If the castle were truly well-known, its fate would have been a topic of local legend or at least speculation, altering how Belle interacts with her world and how the Beast perceives his predicament. The film conveniently maintains the village’s obliviousness until it serves the plot’s dramatic conclusion, leaving us to wonder about the geographical and historical inconsistencies of this enchanted French countryside.

9. **Roger And Anita’s Mysterious Fortune***101 Dalmatians* culminates in a heartwarming, if logistically perplexing, resolution: Roger and Anita, along with their original two Dalmatians, Pongo and Perdita, end up adopting all 99 puppies, bringing their total canine count to 101. They then relocate to a spacious country house, presumably to accommodate their enormous, rapidly growing family. While the sentiment is undeniably sweet, a cold splash of reality hits when one considers the economics of this arrangement.

Roger is explicitly portrayed as a struggling songwriter. His career trajectory isn’t exactly a meteoric rise to fame, and Anita’s profession is never even mentioned. Yet, they suddenly find themselves managing an overwhelming number of dogs, each with significant financial needs. Imagine the cost of feeding 101 Dalmatians—that’s an industrial-sized amount of dog food. Then there are veterinary bills, grooming expenses, and the sheer logistical nightmare of managing waste and general care for such a massive pack.

The film hints at some financial success for Roger at the very end, as his catchy “Cruella De Vil” song becomes a hit. But is one popular song truly enough to sustain a family, a large country estate, and an entire army of Dalmatians for the foreseeable future? The move to the country house itself would be a substantial expense. This financial leap stretches the bounds of belief, even for a cartoon.

It forces us to question the basic economic framework of this delightful world. Are we to assume that fame for a single song in this universe grants unlimited wealth? Or that the practicalities of pet ownership simply don’t apply when the animals are adorable and the story is uplifting? This plot hole, while often overlooked in the rush of the happy ending, presents a stark contrast between fairy tale fantasy and the harsh realities of caring for 101 hungry, playful puppies.

10. **Why Doesn’t Woody Remember?***Toy Story* presents us with a deeply emotional exploration of a toy’s purpose and relationship with its owner. Woody, the classic pull-string cowboy, is depicted as Andy’s most cherished and longest-owned toy, having been in the family for years. Yet, throughout the original film and much of the sequel, Woody appears to have no memory of any previous owners or even the rich history of his own character, the star of an old TV show. This stands in stark contrast to other characters, most notably Jessie.

Jessie, the feisty cowgirl, carries profound and heartbreaking memories of her previous owner, Emily, whose eventual abandonment deeply scarred her. Her backstory, delivered in the poignant “When She Loved Me” sequence, is central to her character arc and motivation. This emotional depth, tied to a past owner, makes Woody’s lack of similar recollection perplexing, especially given his age and apparent rarity as a collectible.

In *Toy Story 2*, we learn that Woody is a highly valuable, vintage toy from “Woody’s Roundup.” One would expect such a venerable toy to possess a wealth of memories spanning decades and multiple owners, perhaps even from his time on a toy store shelf or in production. However, he only seems to recall Andy. This inconsistency becomes even more pronounced when, after moving to Bonnie’s house in *Toy Story 3*, Woody quickly develops a fierce loyalty and clear memories associated with her, similar to his bond with Andy.

Does toy memory activate only with the *current* owner, wiping the slate clean with each new child? If so, why does Jessie remember Emily so vividly, and why does Woody so strongly remember Andy *after* being passed on to Bonnie? It suggests a selective amnesia or a convenient narrative choice that allows Woody’s character to remain solely focused on his relationship with Andy, thus simplifying the emotional landscape, but creating a systemic contradiction in the established rules of toy consciousness.

11. **Aladdin Doesn’t Need to Become a Prince…Again**The very premise of *Aladdin* hinges on our titular hero’s desire to become a prince, a wish he makes to the Genie to win the hand of Princess Jasmine. The Genie, in his infinite cosmic power, grants this wish, transforming Aladdin into “Prince Ali.” However, a significant plot hole emerges later in the film, particularly towards the climax, which throws the very nature of Genie’s magic into question.

After Jafar briefly seizes control of the lamp and exposes Aladdin’s true identity, Aladdin expresses profound doubt about his princely status. He laments that without the Genie, he’s “just Aladdin” and worries about the implications if everyone discovers he’s not “really” a prince. Crucially, near the film’s conclusion, as Aladdin contemplates using his third and final wish to free the Genie, the Genie himself suggests that Aladdin could use the wish to “make him a prince AGAIN.”

This proposal makes absolutely no sense if the Genie’s initial wish was truly granted. When Aladdin wished to become a prince, he didn’t ask to *look* like a prince, or *seem* like one, or be a *fake* prince. He asked to *be* a prince. If the Genie, an all-powerful being, genuinely granted this wish, then Aladdin *was* a true prince. At what point did this wish wear off? Did his princely status vanish simply because Jafar exposed him, or because he lost temporary possession of the lamp?

The film doesn’t offer any clear explanation, forcing us to concoct theories about the ephemeral nature of Genie’s magic or the specific wording of wishes. If Aladdin wished to be a flower pot, would he revert to his human form if people found out he wasn’t “born” a flower pot? The inconsistency undermines the permanence of the Genie’s power and suggests that perhaps the wish only ever created a facade, rather than a true transformation of identity or status. It’s a fundamental contradiction that leaves us questioning the magical mechanics of Agrabah.

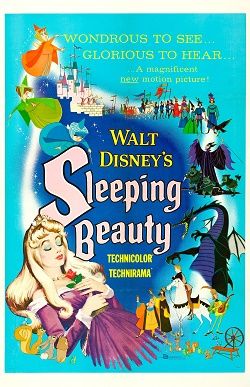

12. **Why Did the Fairies Bring Aurora Home Before Sunset on Her Birthday?**In *Sleeping Beauty*, the nefarious Maleficent, slighted by not receiving an invitation to Princess Aurora’s christening, curses the infant princess to her finger on a spinning wheel and die before the sun sets on her sixteenth birthday. To mitigate this dire prophecy, the three good fairies—Flora, Fauna, and Merryweather—heroically whisk baby Aurora away, raising her in a secluded cottage deep in the forest, living as peasant girls for sixteen years to protect her from Maleficent’s wrath.

Their entire plan hinges on keeping Aurora safe until her sixteenth birthday *has passed*. Yet, in a baffling display of oversight, the fairies decide to bring Aurora back to the castle *just before sunset* on her sixteenth birthday. They know the precise deadline for the curse, having meticulously counted the days and shielded her for years. Why, then, would they choose such a perilous timing for her return, especially given the heightened magical activity and Maleficent’s undeniable focus on that exact moment?

This decision isn’t just poor planning; it’s a catastrophic act of self-sabotage that feels entirely contrived to push the plot forward. Surely, the most logical and safe course of action would have been to wait until a minute *after* sunset, or even the morning after, to ensure the curse had completely expired. Their immense magical powers, their wisdom, and their years of dedicated protection seem to evaporate in this single, critical moment, directly leading to Aurora’s fateful encounter with the spinning wheel.

It raises questions about the competence of these supposedly wise guardians and the internal logic of the magical defense. Did they simply forget the importance of the *after* sunset clause? Or was it an arbitrary narrative necessity that sacrificed the characters’ intelligence for dramatic tension? This frustrating detail, an easily avoidable mistake, casts a long shadow over the fairies’ otherwise diligent efforts, highlighting a systemic narrative contradiction in their approach to a life-or-death prophecy.

And there you have it, fellow film fanatics! Another deep dive into the enchanting, yet sometimes utterly baffling, worlds of Disney. While these magical kingdoms often sweep us away with their charm and wonder, it’s clear that even the most beloved tales aren’t immune to a few head-scratching moments. From the financial impossibilities of caring for 101 Dalmatians to the puzzling age of a cursed prince, these plot holes don’t diminish our love for these films, but rather add a layer of delightful scrutiny to our rewatches. They transform passive viewing into an active quest for logical coherence, proving that even with a dash of pixie dust, a good story still benefits from a solid foundation. So, the next time you settle in for a Disney classic, keep your eyes peeled – you might just spot the next unbelievable inconsistency that makes you say, “huh, now that you mention it…”