The story of the United States is not merely a chronicle of events, but a dynamic narrative of continuous transformation and profound reconfigurations. From its ancient origins, shaped by vast Indigenous civilizations, to its current status as a complex federal republic, America has consistently redefined its physical, political, and social landscapes. This journey reflects a nation perpetually under construction, where foundational ideas and structures have been both vigorously defended and fundamentally reshaped in response to evolving internal and external pressures.

Indeed, to understand America is to grasp its inherent dynamism, a constant interplay between enduring ideals and the practicalities of a diverse, expanding population. This article endeavors to trace these epochal shifts, offering an in-depth, analytical perspective characteristic of The Atlantic’s comprehensive approach. We will delve into the historical and cultural contexts that underpin these transformations, exploring how each era has laid groundwork, introduced new challenges, and ultimately, redefined what it means to be American.

Our examination begins not with colonial shores but with the deep past, acknowledging the rich tapestry of life that predated European arrival. We will then journey through the pivotal moments of nation-building, conflict, and societal re-evaluation that have collectively crafted the United States, illuminating the threads of continuity and rupture that run through its history, serving as a metaphorical ‘tearing up and replacement’ of old paradigms with new realities.

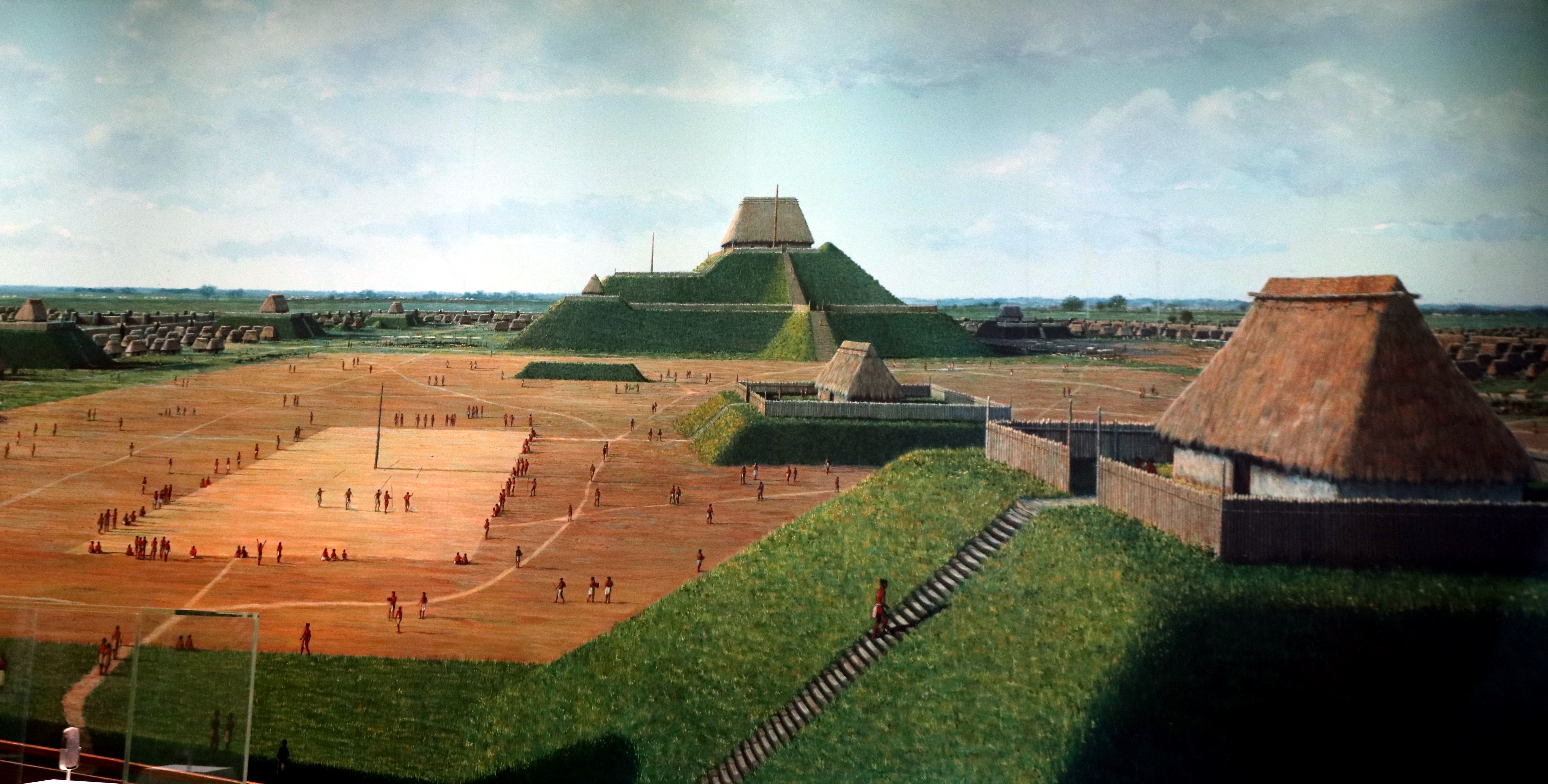

1. **The Deep Roots: Indigenous Civilizations Before European Contact**Long before European sails dotted the Atlantic horizon, North America was a vibrant mosaic of sophisticated Indigenous civilizations, a testament to millennia of human adaptation and innovation. “Paleo-Indians migrated from North Asia to North America over 12,000 years ago, and formed various civilizations,” laying the groundwork for diverse cultures that flourished across the continent. These early inhabitants developed complex societies, economies, and spiritual traditions, deeply interconnected with the land and its resources.

Around 11,000 BC, the widespread Clovis culture emerged, marking a significant early chapter in the continent’s human story. As centuries unfolded, “Indigenous North American cultures grew increasingly sophisticated,” demonstrating remarkable ingenuity in their societal structures and agricultural practices. Notable examples include the Mississippian cultures in the midwestern, eastern, and southern regions, the Algonquian in the Great Lakes region and along the Eastern Seaboard, and the Hohokam and Ancestral Puebloans who mastered the challenges of the Southwest.

Estimates of the Native population before European contact highlight the sheer scale of these established societies, ranging “from around 500,000 to nearly 10 million.” This demographic reality underscores a foundational truth: the land that would become the United States was far from an empty wilderness. Instead, it was a densely populated and culturally rich continent, whose original inhabitants crafted enduring legacies that continue to influence the nation’s identity, often serving as the first, overlooked ‘foundations’ upon which later structures were built.

Read more about: Alabama Unpacked: Dissecting the Deep South’s Evolving Landscape, from Moundville to Marshall Space Flight Center

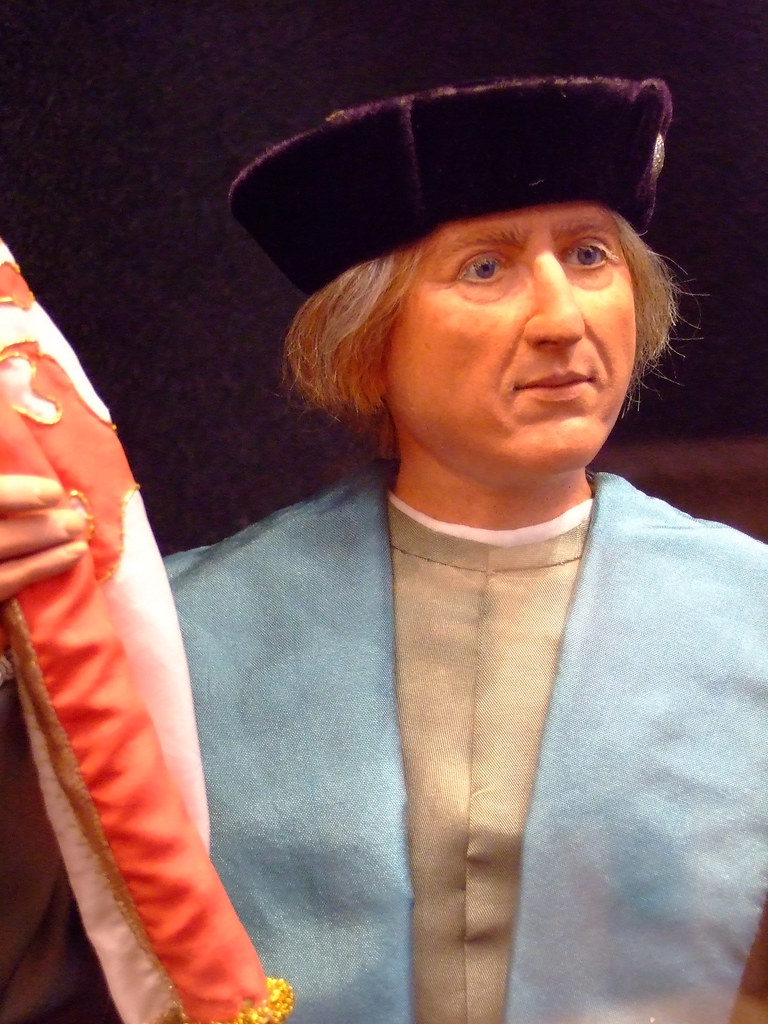

2. **The Crucible of Colonialism: European Footholds and Early Conflicts**The arrival of Europeans marked a dramatic new chapter, initiating a complex interplay of exploration, colonization, and profound conflict across the continent. “Christopher Columbus began exploring the Caribbean for Spain in 1492,” paving the way for Spanish settlements and missions stretching “from what are now Puerto Rico and Florida to New Mexico and California.” The establishment of “Spanish Florida, chartered in 1513,” represents the first European colonial effort in what is now the continental United States, with Saint Augustine founded in 1565 as Spain’s first permanent town.

British colonization, which would ultimately prove the most impactful for the future United States, commenced with “the Virginia Colony (1607) and the Plymouth Colony (Massachusetts, 1620).” These ventures were not isolated, however, as other European powers also staked their claims. France established permanent settlements along the Great Lakes and Mississippi River, including New Orleans. The thriving Dutch colony of New Nederland, settled in 1626, and the small Swedish colony of New Sweden, settled in 1638, further diversified the colonial landscape, creating a patchwork of European ambitions.

Within these nascent colonies, important precedents for self-governance began to take root. “The Mayflower Compact in Massachusetts and the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut established precedents for local representative self-governance and constitutionalism,” ideas that would prove critical in the coming centuries. Yet, this era was also defined by immense challenges: “European settlers in what is now the United States experienced conflicts with Native Americans,” leading to periods of both cooperation and devastating warfare. Simultaneously, along the eastern seaboard, settlers engaged in the brutal “Atlantic slave trade,” forcibly migrating Africans to supply the labor force for plantation economies, a practice that would engrain a deep and tragic legacy into the fabric of the emerging nation. The administration of these “original Thirteen Colonies” by Crown-appointed governors, despite local elections, brewed discontent that would eventually erupt, reshaping the very nature of governance.

3. **Forging a Nation: Revolution, Ideals, and the Birth of a Republic**The seeds of revolution were sown in the aftermath of the French and Indian War, as Britain sought to assert greater control over its distant American colonies. This increased imperial oversight met with fierce “colonial political resistance,” fueled by grievances that went to the heart of perceived rights. “One of the primary colonial grievances was a denial of their rights as Englishmen, particularly the right to representation in the British government that taxed them,” igniting a powerful movement for self-determination.

In a display of mounting dissatisfaction, the First Continental Congress convened in 1774, instituting a colonial boycott of British goods that proved effective. The British response, an attempt to disarm the colonists, directly led to the 1775 Battles of Lexington and Concord, igniting the American Revolutionary War. The Second Continental Congress then made the pivotal decision to declare independence, a momentous act formally adopted on “July 4, 1776,” with the Declaration of Independence drafting committee including Thomas Jefferson.

At the heart of this revolution were deeply held Enlightenment ideals. “The political values of the American Revolution included liberty, inalienable individual rights; and the sovereignty of the people; supporting republicanism and rejecting monarchy, aristocracy, and all hereditary political power; civic virtue; and vilification of political corruption.” Influential figures, the “Founding Fathers of the United States,” drew inspiration from Classical, Renaissance, and Enlightenment philosophies, articulating a vision for a new kind of government founded on principles of self-governance and individual freedom. This era, therefore, saw a profound ‘replacement’ of monarchical authority with republican aspirations.

The initial governmental structure, the “Articles of Confederation, was ratified in 1781 and formally established a decentralized government that operated until 1789,” but its limitations soon became apparent. To address these deficiencies, “The U.S. Constitution was drafted at the 1787 Constitutional Convention,” going into effect in 1789. This landmark document established a federal republic with three separate branches and a system of checks and balances, designed to prevent the concentration of power. The subsequent adoption of the Bill of Rights in 1791 assuaged concerns about centralized authority, while George Washington’s actions, including his resignation as commander-in-chief and refusal of a third term, set crucial precedents for the supremacy of civil authority and the peaceful transfer of power.

4. **A Nation’s Embrace: Westward Expansion and the Louisiana Purchase**The early 19th century witnessed a dramatic shift in the physical boundaries and national psyche of the United States, driven by an inexorable push westward. Fueled by a burgeoning population and a powerful, almost spiritual conviction, “American settlers began to expand westward in larger numbers, many with a sense of manifest destiny.” This belief in a divinely ordained right to expand across the North American continent profoundly shaped both policy and perception, seeing the ‘replacement’ of unexplored or foreign-controlled lands with American dominion.

Territorial acquisitions rapidly transformed the nation’s footprint. The monumental “Louisiana Purchase of 1803 from France nearly doubled the territory of the United States,” opening vast new lands for settlement. Further consolidating its boundaries, the War of 1812, though fought to a draw, solidified American sovereignty, and “Spain ceded Florida and its Gulf Coast territory in 1819.” These acquisitions profoundly altered the geographical imagination of the young republic, cementing its continental ambitions.

However, this expansion came at a devastating cost for the continent’s original inhabitants. “As Americans expanded further into territory inhabited by Native Americans, the federal government implemented policies of Indian removal or assimilation.” President Andrew Jackson’s “Indian Removal Act of 1830” epitomized this brutal approach, leading to the infamous “Trail of Tears (1830–1850).” During this forced march, “an estimated 60,000 Native Americans living east of the Mississippi River were forcibly removed and displaced to lands far to the west, causing 13,200 to 16,700 deaths,” representing a catastrophic human cost of manifest destiny.

Further territorial gains followed, including the “annex[ation of] the Republic of Texas in 1845” and the “1846 Oregon Treaty” that secured the American Northwest. The “Mexican–American War (1846–1848)” resulted in a decisive U.S. victory, with Mexico recognizing American sovereignty over Texas, New Mexico, and California in the “1848 Mexican Cession,” which also included lands that would become Nevada, Colorado, and Utah. This period of rapid territorial growth, exemplified by the “California gold rush of 1848–1849,” spurred massive migration but also intensified conflicts, including the “California genocide of thousands of Native inhabitants,” demonstrating the violent undercurrents of westward expansion.

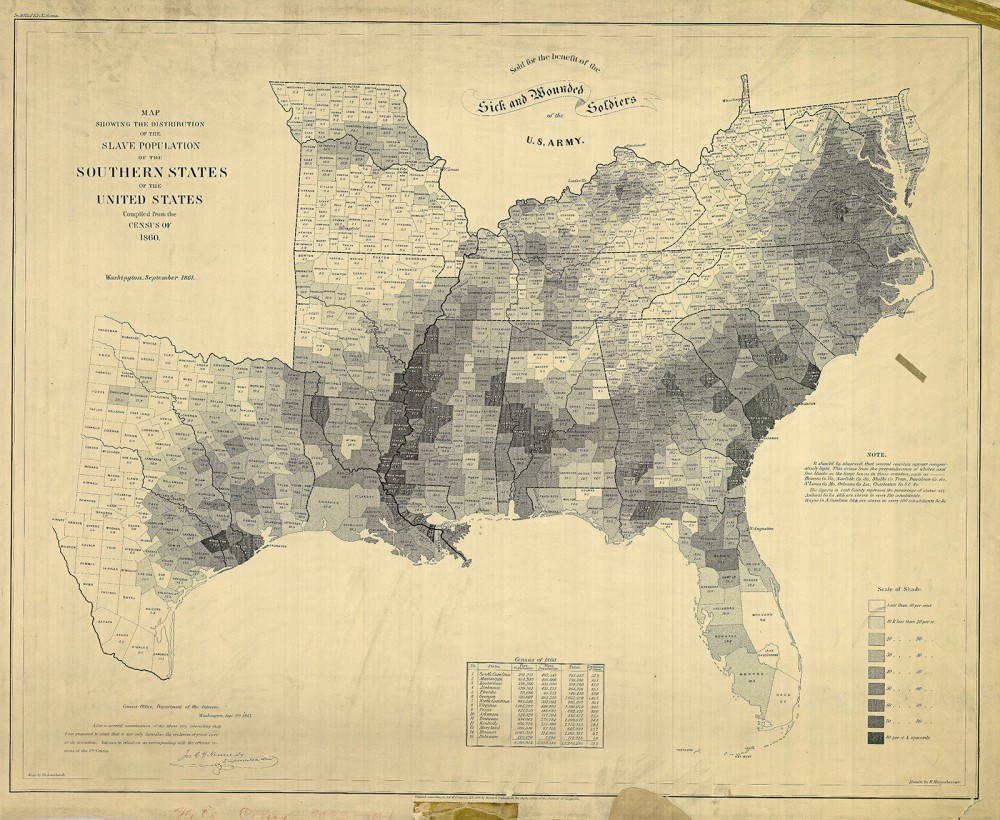

5. **The Irreconcilable Divide: Slavery, Sectionalism, and Civil War**The expansion of the United States across the continent tragically coincided with an increasingly entrenched and divisive debate over the institution of slavery. “During the colonial period, slavery had been legal in the American colonies, becoming the main labor force in the large-scale, agriculture-dependent economies of the Southern Colonies from Maryland to Georgia.” While the practice began to be questioned during the American Revolution and an active abolitionist movement gained traction in the North, the economic realities of the South painted a starkly different picture.

By the mid-19th century, the chasm between North and South over slavery had become profound and seemingly unbridgeable. “Support for slavery had strengthened in Southern states, with widespread use of inventions such as the cotton gin (1793) having made slavery immensely profitable for Southern elites.” This economic imperative intertwined with social and political ideologies, creating a powerful, vested interest in perpetuating the system, directly contrasting with the North’s industrializing economy and moral opposition.

Throughout the 1850s, national legislative and judicial actions further inflamed this sectional conflict. The “Fugitive Slave Act of 1850” mandated the forcible return of escaped slaves, alienating Northerners, while the “Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854” effectively gutted the anti-slavery provisions of the Missouri Compromise. The Supreme Court’s notorious “Dred Scott decision of 1857” ruled against a slave brought into free territory, declaring the entire Missouri Compromise unconstitutional. These actions, perceived as egregious expansions of slavery’s reach, exacerbated tensions and pushed the nation closer to fracture, foreshadowing a violent ‘replacement’ of the existing political order.

These mounting antagonisms culminated in the cataclysmic “American Civil War (1861–1865).” Beginning with South Carolina, “11 slave-state governments voted to secede from the United States in 1861, joining to create the Confederate States of America,” while the remaining states stayed loyal to the Union. The war erupted in April 1861 with the bombardment of Fort Sumter. A pivotal turning point came with the “Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863,” which broadened the war’s scope to include the liberation of enslaved people. Union victories at Vicksburg and Gettysburg in 1863, and the final Confederate surrender in 1865 after the Battle of Appomattox Court House, ultimately preserved the Union and abolished slavery nationally, fundamentally reshaping the nation’s moral and political landscape.

6. **Rebuilding and Remaking: Reconstruction, Industrial Boom, and Immigration Waves**The conclusion of the Civil War heralded an era of profound transformation, encompassing both the arduous work of national reunification and an explosive period of economic and demographic change. “Efforts toward reconstruction in the secessionist South had begun as early as 1862,” but it was the post-assassination Lincoln era that saw the ratification of “three Reconstruction Amendments to the Constitution… to protect civil rights.” These amendments codified the national abolition of slavery, guaranteed equal protection under the law, and prohibited racial discrimination in voting, profoundly ‘rebuilding’ the legal and social foundations of the nation and enabling “African Americans [to take] an active political role in ex-Confederate states.”

Simultaneously, the nation embarked on ambitious infrastructure projects that would physically knit the country together. “National infrastructure, including transcontinental telegraph and railroads, spurred growth in the American frontier,” facilitating rapid westward settlement. The “Homestead Acts” further accelerated this expansion, giving away “nearly 10 percent of the total land area of the United States… free to some 1.6 million homesteaders,” dramatically altering land ownership and usage patterns across the vast new territories.

This period also witnessed an unprecedented demographic shift driven by mass immigration. “From 1865 through 1917, an unprecedented stream of immigrants arrived in the United States, including 24.4 million from Europe.” These new arrivals, diverse in origin, settled across the country; “New York City and other large cities on the East Coast became home to large Jewish, Irish, and Italian populations,” while Germans and other Central Europeans migrated to the Midwest. Concurrently, the “Great Migration” saw “millions of African Americans [leave] the rural South for urban areas in the North,” seeking economic opportunity and an escape from racial oppression, further reconfiguring the nation’s social geography.

Accompanying these demographic shifts was an “explosion of technological advancement accompanied by the exploitation of cheap immigrant labor,” which fueled a “rapid economic expansion during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.” This period, often called the Gilded Age, saw the U.S. economy “outpace the economies of England, France, and Germany combined,” driven by tycoons in industries like railroad, petroleum, and steel. However, this immense wealth accumulation also resulted in “significant increases in economic inequality, slum conditions, and social unrest,” giving rise to powerful labor unions and socialist movements, ultimately leading to the “Progressive Era, which was characterized by significant reforms” aimed at addressing these societal imbalances.

Concurrently, the United States expanded its global reach, acquiring new territories beyond its continental borders. “Pro-American elements in Hawaii overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy; the islands were annexed in 1898.” In the same year, following its victory in the Spanish-American War, the U.S. gained “Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam” from Spain. Additional acquisitions included American Samoa in 1900 and the U.S. Virgin Islands, purchased from Denmark in 1917, marking the nation’s emergence as a significant imperial power and a literal ‘replacement’ of indigenous or colonial rule with American sovereignty, further shaping its identity and global responsibilities.

7. **Ascension to Global Power: World Wars, Depression, and a Reshaped World Order (1917–1945)**As the 20th century progressed, the United States, having expanded its continental and imperial reach, increasingly engaged in global affairs, leading to two world wars and an unprecedented economic crisis. Its entry into World War I in 1917, alongside the Allies, decisively shifted the balance of power, marking a pivot from isolationism towards international engagement. Domestically, a constitutional amendment in 1920 granted nationwide women’s suffrage, fundamentally expanding the democratic landscape.

The post-war optimism gave way to profound economic hardship with the Wall Street Crash of 1929, triggering the Great Depression. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal represented an unprecedented ‘replacement’ of laissez-faire policies with sweeping recovery programs, employment relief, and financial reforms. This redefined the federal government’s role in citizens’ lives, establishing a new social contract and a sense of shared national responsibility.

World War II again demanded American intervention. Initially neutral, the U.S. supplied war materiel to the Allies, a commitment deepened by Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. America’s full entry transformed its industrial capacity into an arsenal of democracy, and its scientific prowess led to nuclear weapons, ending the war in August 1945. Emerging economically strengthened, the U.S. played a pivotal role among the “Four Policemen” in planning the post-war world, solidifying its status as a major global power.

8. **The Bipolar World: Cold War Tensions and the Stirrings of Social Revolution (1945–1991)**Post-World War II, the U.S. and Soviet Union emerged as rival superpowers, initiating the Cold War, a period of intense geopolitical tension. America’s containment policy aimed to limit USSR influence, engaging in regime changes and triumphing in the Space Race with the 1969 Moon landing. This global struggle represented a constant ‘recalibration’ of international relations, shifting from overt military conflict to proxy wars and ideological battles.

Domestically, the post-war era brought economic growth, urbanization, and population booms, yet deep-seated injustices persisted. The civil rights movement, led by Martin Luther King Jr. in the early 1960s, challenged segregation. President Lyndon B. Johnson’s “Great Society” responded with groundbreaking laws and policies to counteract institutional racism, striving for a more equitable society.

This period also saw the counterculture movement, liberalizing attitudes towards drug use and uality, and fostering widespread opposition to the Vietnam War, leading to U.S. withdrawal in 1975 and the end of conscription. Concurrently, women’s roles shifted, significantly increasing female paid labor participation by 1985, irrevocably altering the social and economic fabric.

The Cold War concluded with the Fall of Communism and the Soviet Union’s dissolution (1989–1991). This left the United States as the world’s sole superpower, cementing its unparalleled global influence across political, cultural, economic, and military domains. This marked a profound ‘replacement’ of a bipolar world, ushering in the “American Century.”

9. **Navigating the New Millennium: Contemporary Challenges and Unrelenting Evolution (1991–Present)**

The post-Cold War era brought remarkable dynamism and challenges, reflecting a continuous ‘reconfiguration’ of America’s identity. The 1990s saw the longest economic expansion, reduced crime rates, and profound technological innovation, including the World Wide Web, rapid microprocessor evolution, and the Human Genome Project. Online trading with Nasdaq further underscored this digital and scientific transformation, reshaping daily life and economic interaction.

This ascendancy was punctuated by acute crises. After the 1991 Gulf War, the September 11 attacks in 2001 led to the “war on terror” and military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq. These events fundamentally altered U.S. foreign policy and domestic security, demanding a ‘replacement’ of old security assumptions with complex new realities and a re-evaluation of global engagement.

Domestically, the 21st century presented its own profound challenges. The 2007 housing bubble triggered the Great Recession, the largest economic contraction since the Great Depression. More recently, increased political polarization and democratic backsliding culminated in the January 2021 Capitol attack, where insurrectionists sought to prevent the peaceful transfer of power, underscoring ongoing struggles to reaffirm core democratic principles against internal pressures.

10. **The Grand Tapestry: America’s Expansive Geography and Diverse Climates**The United States’ vast physical expanse profoundly shapes its identity, a geography defining its character and development. As the world’s third-largest country, spanning over 3.1 million square miles, it encompasses diverse landscapes. From the Atlantic coastal plain, through the Piedmont and Appalachian Mountains, the Mississippi River System bisects central plains stretching into the fertile Great Plains. This immense backdrop has been continuously reshaped by both human interaction and profound natural forces.

Western topography includes the majestic Rocky Mountains, rising above 14,000 feet, harboring the Yellowstone Caldera. Beyond are arid expanses like the Great Basin and three major deserts, while the Colorado River carves the overwhelming Grand Canyon. The Cascade and Sierra Nevada ranges define the Pacific edge; California hosts both the lowest and highest points in the contiguous U.S., showcasing dramatic geological variety. Alaska’s Denali and Hawaii’s volcanic islands extend this diversity.

This vastness fosters an extraordinary array of climates, from humid continental to tropical, encompassing semi-arid, alpine, arid, Mediterranean, and oceanic zones. Yet, this meteorological tapestry brings significant challenges: the U.S. experiences more high-impact extreme weather incidents than any other country, including hurricanes and tornadoes. Climate change has led to increased heat waves and persistent droughts, highlighting a concerning reconfiguration of atmospheric conditions and the continuous need for adaptive strategies.

11. **Safeguarding Nature: Biodiversity and Environmental Stewardship**The United States, among the world’s megadiverse countries, boasts an astonishing wealth of biodiversity, a natural heritage demanding continuous stewardship. Approximately 17,000 species of vascular plants thrive across the contiguous U.S. and Alaska, alongside over 1,800 flowering plant species in Hawaii, many endemic. This vibrant flora complements a rich fauna, including 428 mammal species, 784 birds, 311 reptiles, 295 amphibians, and 91,000 insect species, forming crucial interconnected ecosystems vital for global ecological balance.

In recognition of this invaluable natural capital, the nation has developed an extensive conservation framework. It is home to 63 national parks and hundreds of other federally managed monuments, forests, and wilderness areas, overseen by the National Park Service. Roughly 28% of the country’s land is publicly owned, primarily in the Western States, mostly protected for conservation, though some is leased for commercial use. This represents a continuous negotiation over land use and preservation.

Despite efforts, the U.S. grapples with complex environmental issues, from debates on non-renewable resources and pollution to biodiversity loss and climate change, necessitating comprehensive strategies. The EPA addresses most environmental issues, while the 1964 Wilderness Act and the 1973 Endangered Species Act provide robust protections. However, the nation’s 2024 Environmental Performance Index ranking of 35th among 180 countries signals a continuous need for adaptive strategies and renewed dedication to ecological stewardship.

12. **The Enduring Framework: Government, Politics, and Democratic Foundations**The U.S. governmental structure stands as a testament to enduring foundational principles, a federal republic continuously adapted since inception, rooted in Enlightenment ideals. Comprising 50 states, Washington, D.C., and several territories, it is the world’s oldest surviving federation. Its presidential system has influenced many newly independent states. The U.S. Constitution, the supreme legal document, forms the bedrock of this liberal democracy, an evolving experiment in self-governance.

At its heart is the federal government, headquartered in Washington, D.C., composed of three distinct branches: legislative, executive, and judicial. The Constitution establishes a separation of powers with checks and balances, meticulously designed to prevent excessive authority, ensuring a balance constantly tested and reinforced throughout history. This tripartite structure defines American governance, embodying a commitment to divided authority and accountability.

The legislative U.S. Congress is bicameral, reflecting both population-based (House: 435 members, 2-year terms) and equal state representation (Senate: 100 members, 6-year terms). Congress wields significant powers: making federal law, declaring war, approving treaties, and controlling the national purse. Its non-legislative functions include investigating and overseeing the executive branch, often through bipartisan committees, demonstrating a dynamic interplay of accountability.

Beyond federal architecture, federalism grants substantial autonomy to the 50 states. Furthermore, 574 Native American tribes possess sovereignty rights across 326 reservations, reflecting an evolving relationship with the federal government. Since the 1850s, Democratic and Republican parties have dominated, their platforms continually ‘torn down and replaced’ in response to societal shifts. American values, rooted in Enlightenment-inspired democratic tradition, emphasize liberty and people’s sovereignty, forming an adaptable foundation.

Read more about: Strategic Foundations: Understanding the U.S. Military’s Global Power and Operational Framework

As we traverse the vast historical and geographical expanse of the United States, we observe a nation perpetually in motion, a testament to the continuous process of ‘tearing up and replacing’ its landscapes, social contracts, and political ideologies. From ancient Indigenous paths to 21st-century digital highways, America has constantly adapted, innovated, and reformed, often through conflict and profound transformation. The enduring strength of its democratic ideals, remarkable biodiversity, and dynamic economy remain intertwined with its capacity for self-reflection and willingness to rebuild from challenges. This relentless reimagining of itself is the very essence of the American experience.