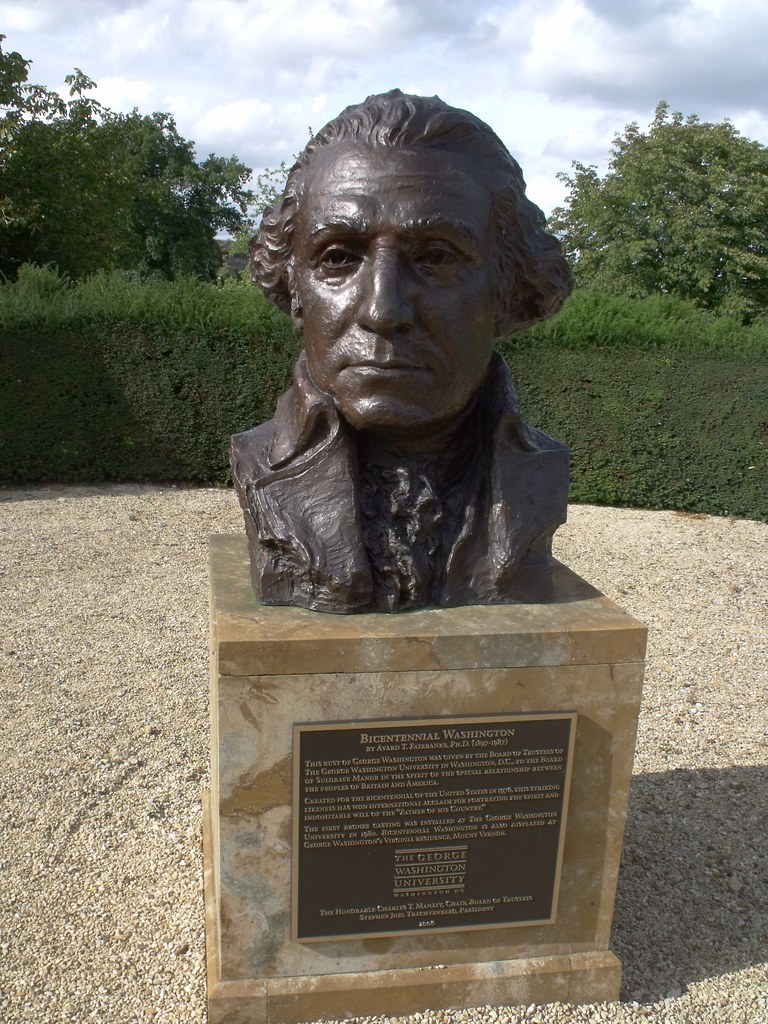

George Washington. The very name conjures images of unyielding resolve, unwavering leadership, and the birth of a nation. As one of America’s Founding Fathers and its first president, Washington’s journey was nothing short of monumental, a testament to what a single individual, guided by principle and purpose, can achieve amidst staggering odds. His story isn’t just a dry historical account; it’s a thrilling epic of personal growth, military prowess, and the forging of an enduring democratic ideal. It’s a narrative packed with crucial decisions and defining moments that shaped not only his destiny but also the very fabric of the United States.

Before he was the revered general or the venerable president, Washington was a man forged in the crucible of colonial Virginia, learning, failing, and adapting. Every step of his early life and career, from his familial struggles to his baptism by fire in frontier conflicts, contributed to the extraordinary leader he would become. Understanding these foundational experiences is key to appreciating the depth of his character and the sheer magnitude of his accomplishments. His path was complex, marked by both personal ambition and profound dedication to public service, setting precedents that reverberate to this day.

Join us as we embark on an in-depth exploration of 12 pivotal chapters in the life of George Washington, examining the trials, triumphs, and transformative decisions that cemented his legendary status. This first section will illuminate his early life, his initial forays into military command, his rise as a prominent planter and politician, and the intense challenges he faced as the newly appointed commander-in-chief of the Continental Army during the tumultuous early years of the American Revolutionary War. Prepare to dive deep into the fascinating genesis of an American icon.

1. **Formative Years and Early Ambition**Born on February 22, 1732, at Popes Creek in Westmoreland County, Virginia, George Washington’s early life was marked by a somewhat unconventional family dynamic. He was the first of six children born to Augustine and Mary Ball Washington, and his father already had four children from a previous marriage. Intriguingly, Washington was not particularly close to his father, rarely mentioning him in later years, and maintained a fractious relationship with his mother. However, he fostered a strong bond with his older half-brother, Lawrence, which proved to be a significant influence on his path.

The family’s movements from Little Hunting Creek to Ferry Farm near Fredericksburg, Virginia, set the stage for his upbringing. His father’s death in 1743 was a pivotal moment, as it meant Washington did not receive the formal education in England that his elder half-brothers had enjoyed. Instead, he attended the Lower Church School in Hartfield, where he honed practical skills. He learned mathematics and land surveying, becoming a talented draftsman and mapmaker, skills that would prove invaluable throughout his life and career.

During his teenage years, Washington meticulously compiled over a hundred rules for social interaction, known as ‘The Rules of Civility,’ copied from an English translation of a French guidebook. This early dedication to self-improvement and decorum highlights a disciplined mind already focused on reputation and conduct. By early adulthood, his biographer Ron Chernow noted his writing exhibited “considerable force” and “precision.” These details reveal a young man driven to excel and prepare himself for a prominent role, even without the traditional markers of elite education.

Washington’s connection with the prominent Fairfax family, particularly William Fairfax, who became his patron and surrogate father, further opened doors for him. He gained invaluable surveying experience in the Shenandoah Valley and received a surveyor’s license from the College of William & Mary in 1749. This led to his appointment as surveyor of Culpeper County. Although he resigned from this post in 1750, by 1752, he had already amassed significant land holdings, owning nearly 1,500 acres in the Shenandoah Valley and a total of 2,315 acres. A journey to Barbados with Lawrence, hoping to cure his brother’s tuberculosis, marked his only trip outside mainland North America and, unfortunately, led to him contracting smallpox, leaving his face slightly scarred. Upon Lawrence’s death in 1752, Washington eventually inherited Mount Vernon, which would become his cherished home and a symbol of his return to private life.

Read more about: Gene Simmons’ Malibu Car Crash: Shannon Tweed’s Urgent Health Revelations and His Life After Kiss

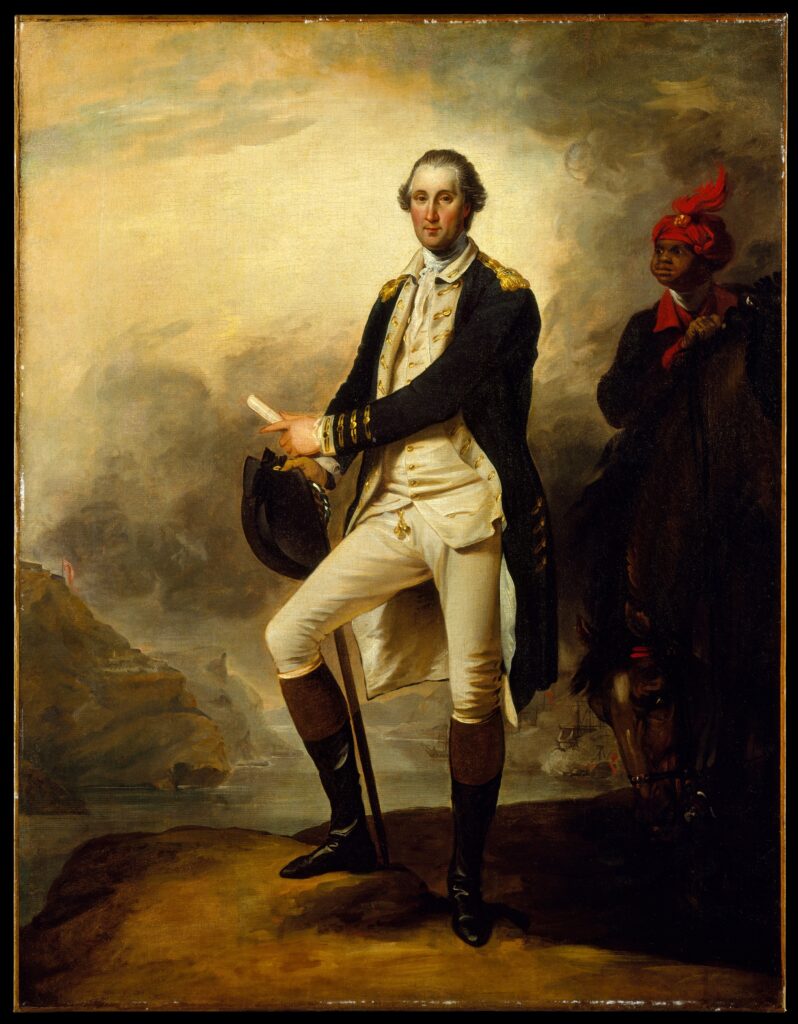

2. **Forging a Commander: The French and Indian War**Inspired by his half-brother Lawrence’s service, George Washington sought a militia commission, marking his true entry into military life. Virginia’s lieutenant governor, Robert Dinwiddie, appointed him a major and commander of one of the four militia districts, thrusting him into the escalating competition between the British and French for control of the Ohio River Valley. This was a volatile frontier, with both empires vying for strategic land, and Washington found himself at the heart of this geopolitical struggle.

In October 1753, Dinwiddie dispatched Washington as a special envoy to demand that French forces vacate lands claimed by the British. This precarious mission, conducted in difficult winter conditions, involved making peace with the Iroquois Confederacy and gathering intelligence. His meeting with Iroquois leader Tanacharison was significant, as Tanacharison bestowed upon him the name Conotocaurius, meaning “devourer of villages”—a name previously given to his great-grandfather. Washington delivered the British demand to the French commander, Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre, who politely but firmly refused to leave. Washington’s report on this mission, published in Virginia and London, brought him a measure of distinction, even as it underscored the intractable nature of the colonial dispute.

The conflict soon escalated. In February 1754, Dinwiddie promoted Washington to lieutenant colonel, making him second-in-command of the 300-strong Virginia Regiment with orders to confront the French at the Forks of the Ohio. This period saw the infamous “Jumonville affair,” where Washington’s small force ambushed a French detachment, killing its commander, Joseph Coulon de Jumonville. This incident, for which Washington unwittingly took responsibility for “assassinating” Jumonville in a French-language surrender document he signed, became the spark that ignited the French and Indian War. The subsequent Battle of Fort Necessity resulted in Washington’s surrender, a humbling early defeat that nonetheless taught him hard lessons about command and diplomacy.

Despite the setbacks, Washington’s reputation for bravery and resilience grew. He volunteered as an aide to General Edward Braddock in 1755 during the ill-fated expedition to expel the French from Fort Duquesne. In the ensuing Battle of the Monongahela, where two-thirds of the British force became casualties and Braddock was killed, Washington displayed immense courage, having two horses shot from under him and his hat and coat pierced by bullets. He rallied the survivors and formed a rear guard, allowing for a retreat that redeemed his reputation among his critics. He passionately sought a royal commission, which the British consistently denied to “colonials,” fostering a growing hostility towards the British military structure and a deep understanding of its strategic and logistical flaws. By the time he resigned his commission in 1758, frustrated by command disputes and lack of advancement, Washington had significantly increased the professionalism of the Virginia Regiment and gained invaluable experience in leadership, self-confidence, and British military tactics, all of which would serve him profoundly in the looming American Revolution.

3. **The Planter and Politician: Wealth, Influence, and Growing Dissent**George Washington’s marriage on January 6, 1759, at the age of 26, to Martha Dandridge Custis, a 27-year-old widow of a wealthy plantation owner, was a transformative event for his personal and economic life. Martha was described as intelligent, gracious, and experienced in managing a planter’s estate, and their union at Mount Vernon proved to be a happy one. This marriage instantly elevated Washington’s financial standing, giving him control over Martha’s one-third dower interest in the substantial 18,000-acre Custis estate, while he also managed the remaining two-thirds for Martha’s children. Consequently, Washington became one of the wealthiest men in Virginia, a status that significantly enhanced his social and political influence.

Beyond the marriage, Washington aggressively expanded his land holdings and agricultural enterprises. At his urging, Governor Lord Botetourt fulfilled an earlier promise, granting land bounties to French and Indian War volunteer militiamen. Washington himself acquired 23,200 acres and later purchased an additional 20,147 acres from veterans, leading to some veterans feeling they had been “duped.” He doubled the size of Mount Vernon to 6,500 acres and, by 1775, had more than doubled its slave population to over one hundred, a complex aspect of his planter identity that he would later come to oppose near the end of his life, providing for their eventual manumission in his will.

As a respected military hero and a substantial landowner, Washington naturally transitioned into local offices and, beginning in 1758, was elected to represent Frederick County in the Virginia House of Burgesses for seven years. Initially, he was not a vocal participant, rarely speaking at or even consistently attending legislative sessions. However, by the 1760s, a notable shift occurred; he became increasingly politically active and emerged as a prominent critic of Britain’s taxation and mercantilist policies, which he perceived as oppressive towards the American colonies. His own economic struggles, including being £1,800 in debt by 1764 due to profligate spending on English luxury goods and low tobacco prices, further fueled his understanding of colonial economic grievances.

His complete reliance on London tobacco buyer and merchant Robert Cary underscored his economic vulnerability. This prompted him to diversify Mount Vernon’s operations between 1764 and 1766, shifting the primary cash crop from tobacco to wheat and expanding into flour milling and hemp farming. A personal tragedy struck in 1773 with the death of his stepdaughter Patsy from epileptic attacks, which, while heartbreaking, allowed him to use part of her inheritance to settle his significant debts. These personal and economic experiences deeply informed his growing opposition to the British Crown, turning a wealthy planter into a committed Patriot ready to challenge imperial authority.

4. **Taking Command: Leading the Continental Army**The American Revolutionary War ignited with the Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, a clarion call that echoed across the colonies. George Washington, swiftly departing Mount Vernon on May 4, made his way to the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia, ready to contribute to the burgeoning rebellion. It was within this historic assembly that a truly monumental decision was made, one that would irrevocably alter the course of American history and cement Washington’s place at its forefront.

On June 14, Congress established the Continental Army, a crucial step in transforming scattered militias into a unified fighting force. The very next day, John Adams, recognizing Washington’s extensive military experience and believing that a Virginian commander would foster greater unity among the disparate colonies, nominated him to be commander-in-chief. This was a unanimous election, a testament to the respect and trust he commanded even at this early stage. Washington, in an act of profound patriotism and selflessness, gave an acceptance speech on June 16, notably declining a salary, though he would later be reimbursed for his expenses. This gesture immediately set a powerful precedent for civic virtue and servant leadership.

With his appointment, Washington faced the formidable task of assembling and organizing his command staff. Congress played a role in choosing his primary officers, including figures like Artemas Ward, Horatio Gates, Charles Lee, Philip Schuyler, and Nathanael Greene. However, Washington quickly recognized and promoted talent, elevating Henry Knox to colonel and chief of artillery due to his impressive knowledge of ordnance. Similarly, the brilliant young Alexander Hamilton, whose intelligence and bravery captivated Washington, was promoted to colonel and appointed his aide-de-camp, a pivotal relationship for the war and the nascent republic.

An early, complex decision involved the enlistment of Black soldiers. Initially, Washington banned the recruitment of both free and enslaved Black individuals into the Continental Army. However, the British, keen to exploit colonial divisions, offered freedom to slaves who joined their forces, as evidenced by Virginia’s colonial governor’s proclamation. In response to this strategic maneuver by the British and the pressing need for troops, Washington swiftly overturned his ban. This critical reversal allowed Black soldiers to serve, and by the end of the war, approximately one-tenth of the Continental Army’s ranks were composed of Black individuals, with some indeed obtaining their freedom through their service. This demonstrated Washington’s pragmatic leadership, adapting his policies to meet the existential demands of the war for independence.

5. **The Crucible of War: Boston to Princeton**Upon Washington’s arrival in Boston on July 2, 1775, he was met with fervent crowds and political ceremony, quickly becoming a symbol of the Patriot cause. However, the reality on the ground was starkly different from the heroic reception. He discovered an army of undisciplined militia, a force ill-prepared for a sustained conflict against the formidable British regulars. In response, Washington, after consulting with his officers, initiated essential reforms suggested by Benjamin Franklin, introducing rigorous military drills and imposing strict disciplinary measures. He was also decisive in promoting deserving soldiers and removing officers deemed incompetent, demonstrating his commitment to building a professional fighting force from the ground up.

The British, under General Thomas Gage (later replaced by General William Howe), occupied Boston, trapped by local militias. Washington, ever the strategist, was eager to cross the frozen Charles River to storm the city. However, he was persuaded against such a risky assault by his generals, who argued against sending untrained militia against well-garrisoned fortifications. Instead, Washington agreed to a brilliant maneuver: securing the Dorchester Heights above Boston. This strategic position, overlooking the British stronghold, made their position untenable. On March 17, a chaotic naval evacuation commenced, with 8,906 British troops, 1,100 Loyalists, and 1,220 women and children departing Boston. Washington entered the city with 500 men, issuing explicit orders against plunder, and notably refrained from exerting military authority, leaving civilian matters to local authorities – a powerful early signal of republican governance.

Following the triumph at Boston, Washington astutely anticipated the British next move: New York City. He arrived there on April 13, 1776, immediately ordering the construction of fortifications and emphasizing respectful treatment of civilians and their property to avoid the abuses that Bostonians had endured under British occupation. The British, however, arrived with an overwhelming force, including over a hundred ships and thousands of troops, effectively laying siege to the city in July. General Howe commanded a massive 32,000 regulars and Hessian auxiliaries, dwarfing Washington’s 23,000 men, who were largely untrained recruits and militia, setting the stage for one of the most desperate periods of the war.

The Battle of Long Island in August saw Howe land 20,000 troops and assault Washington’s flank, inflicting 1,500 Patriot casualties. Washington was forced to retreat to Manhattan. In a moment revealing his steadfast adherence to proper diplomatic protocol, Washington declined to accept a peace negotiation message from Howe that addressed him merely as “George Washington, Esq.,” demanding to be acknowledged as a legitimate military commander. Despite misgivings, he defended Fort Washington, but ultimately lost it, and with his army reduced to just 5,400 troops, he commenced a grueling retreat across the Hudson River and through New Jersey. The winter of 1776-1777 looked bleak, with expiring enlistments and widespread desertions threatening the very existence of the Continental Army, a period when loyalists in New York City even spread rumors of Washington having set fire to the city.

Yet, from this nadir, Washington engineered a stunning reversal. Crossing the icy Delaware River into Pennsylvania, where General John Sullivan reinforced him with 2,000 troops, Washington launched a daring surprise attack on a Hessian garrison at Trenton on December 26, 1776, securing a pivotal victory. Just days later, on January 3, 1777, he followed this up with another audacious strike against British regulars at Princeton, inflicting 273 British casualties. These strategically vital victories at Trenton and Princeton dramatically revived Patriot morale, squashing the British strategy of overwhelming force and generous terms, and irrevocably changed the course of the war. They showcased Washington’s brilliant tactical mind and his unparalleled ability to inspire and lead under the most desperate circumstances.

6. **Enduring the Winter: Valley Forge and Strategic Adaptation**As 1777 drew to a close, Washington and his army of 11,000 men faced arguably their greatest trial: winter quarters at Valley Forge, just north of Philadelphia. It was here, amidst the bitter cold and scarcity, that the Continental Army endured horrific losses, with between 2,000 and 3,000 men succumbing to disease, starvation, and exposure due to a severe lack of food, clothing, and shelter. The ranks dwindled to below 9,000, and morale plummeted, leading to an increase in desertions. This period tested Washington’s leadership to its absolute limits, challenging not only his strategic acumen but also his ability to maintain cohesion and faith within his suffering forces.

This dire situation fueled significant internal criticism and an attempted internal revolt by some of his officers, which prompted certain members of Congress to consider removing Washington from command. His supporters, however, stood firm, and the movement to replace him ultimately failed. This episode, though challenging, underscored the deep loyalty he commanded and the political skill required to navigate such internal pressures while still prosecuting a war. Washington was a master of endurance, holding his army together with sheer will and persistent advocacy.

Faced with the existential threat to his army, Washington launched impassioned pleas to Congress for provisions. He conveyed the urgency of the situation directly to a congressional delegation, detailing the desperate need for supplies. Congress eventually responded, agreeing to strengthen the army’s supply lines and reorganize the crucial quartermaster and commissary departments. Simultaneously, Washington initiated the “Grand Forage of 1778,” a massive operation to collect food from the surrounding region, demonstrating his proactive approach to solving dire logistical problems.

While logistical improvements were underway, a transformative figure emerged: Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben. Appointed Inspector General, von Steuben’s relentless and rigorous drilling turned Washington’s beleaguered recruits into a disciplined and formidable fighting force. His training instilled vital Prussian military tactics and much-needed professionalism into the American ranks, proving to be a critical turning point for the army’s effectiveness. This period at Valley Forge, despite its immense suffering, thus became a forge of discipline and resilience for the Continental Army, emerging stronger and more unified.

By early 1778, the strategic landscape shifted dramatically with France’s official entry into a Treaty of Alliance with the Americans, a diplomatic triumph that promised crucial military and financial aid. In May, General Howe resigned, replaced by Sir Henry Clinton, and the British evacuated Philadelphia for New York that June. Washington, seizing the opportunity, summoned a war council. He ordered a limited strike on the retreating British at the Battle of Monmouth on June 28. Although marred by General Charles Lee’s bungled initial attack, Washington personally rallied his troops and achieved a hard-fought draw. This engagement marked the end of major campaigning in the northern and middle states, as British attention subsequently shifted to the Southern theater, offering Washington a brief respite but setting the stage for new challenges and strategic decisions in the ongoing fight for independence.

7. **Washington the Spymaster: Espionage and the Arnold Betrayal**The Revolutionary War was fought not just on battlefields, but also in a clandestine world of secrets and intelligence. George Washington, ever the pragmatic leader, masterfully stepped into the role of America’s first spymaster, meticulously designing and overseeing an espionage system against the formidable British forces. This crucial, often overlooked, dimension of his strategic genius ensured his forces were often one step ahead, gathering vital intelligence that could turn the tide of battles and save countless lives.

A testament to Washington’s foresight was the formation of the legendary Culper Ring in 1778. Under his direct guidance, Major Benjamin Tallmadge orchestrated this network of covert agents in New York, tasked with collecting sensitive information about British movements and plans. Intelligence from the Culper Ring proved invaluable, most notably saving French forces from a surprise British attack—an attack ironically based on information from one of Washington’s own generals who had turned traitor.

Yet, even Washington’s vigilance couldn’t prevent one of the most infamous betrayals in American history: that of General Benedict Arnold. Arnold, a distinguished veteran of many campaigns, including the invasion of Quebec, had previously shown incidents of disloyalty that Washington, perhaps too trusting, had disregarded. In 1779, Arnold began actively supplying the British spymaster John André with critical information, aiming to facilitate the British capture of West Point, a strategically vital American defensive position on the Hudson River.

The plot culminated on September 21, when Arnold provided André with detailed plans for the garrison. Fortunately, André was captured by alert militia members who discovered the incriminating documents. Upon learning of Arnold’s profound treason, Washington acted with swift, decisive leadership. He immediately recalled all commanders positioned under Arnold at key points around the fort, preempting further complicity. Washington then personally assumed command at West Point, meticulously reorganizing its defenses and shoring up its vulnerabilities, transforming a moment of potential disaster into a display of unflappable resolve.

8. **The Southern Gambit and the Triumph at Yorktown**As the war progressed, the British shifted their strategic focus to the Southern theater, gaining firm control of the South Carolina Piedmont by June 1780. This grave threat was met with invigorated resilience from Washington, boosted by crucial support from allies. The Marquis de Lafayette returned from France with vital ships, men, and supplies, followed by 5,000 veteran French troops led by Marshal Rochambeau landing at Newport, Rhode Island, injecting much-needed strength and expertise.

The stage was set for a pivotal showdown. General Clinton dispatched Benedict Arnold, now a British brigadier general, to Virginia with 1,700 troops to capture Portsmouth and raid Patriot forces. Washington swiftly sent Lafayette south. Washington initially hoped to confront the British in New York, but Rochambeau, with keen strategic understanding, convinced him Lord Cornwallis in Virginia was a more opportune target for a combined French-American assault.

This strategic realignment led to one of military history’s most celebrated marches. On August 19, 1781, Washington and Rochambeau began their audacious march to Yorktown, Virginia. Washington commanded an impressive combined force of 7,800 Frenchmen, 3,100 militia, and 8,000 Continental troops, showcasing collaborative leadership. He often deferred to Rochambeau’s superior experience in siege warfare, yet Rochambeau always respected Washington’s ultimate authority.

By late September, the meticulously planned encirclement was complete: Patriot and French forces had effectively trapped the British Army at Yorktown. Simultaneously, the French navy, in a stunning display of power, emerged victorious at the Battle of the Chesapeake, cutting off any possibility of British escape or reinforcement by sea. The final American offensive commenced with a shot personally fired by Washington, symbolizing the culmination of years of struggle.

The siege ended with a British surrender on October 19, 1781, a profound victory where over 7,000 British soldiers became prisoners. Washington, meticulously negotiating terms for two days, solidified this triumph. Yorktown proved to be the last significant battle of the Revolutionary War, compelling British Parliament to cease hostilities in March 1782 and unequivocally recognizing America’s birth as a free nation.

9. **The Unprecedented Act: Demobilization and Resignation**With the war effectively concluded after Yorktown, peace negotiations began in April 1782, and both British and French forces gradually evacuated. However, a new, internal challenge arose for Washington. In March 1783, he faced the perilous Newburgh Conspiracy, a planned mutiny by American officers dissatisfied with lack of pay. It was a moment threatening to unravel the new nation, but Washington, with characteristic calm and moral authority, successfully quelled the unrest, reminding his officers of their higher principles.

Washington meticulously submitted an account of $450,000 in expenses he personally advanced to the army. While settled, the account included vague large sums and even his wife’s expenses, highlighting the extensive personal cost of his dedication. This reinforced his integrity and set a powerful precedent for public service.

American independence was officially recognized with the Treaty of Paris on September 3, 1783. Washington undertook the solemn duty of disbanding his army with profound respect. On November 2, he delivered a heartfelt farewell address, acknowledging his soldiers’ sacrifices. He then oversaw the final evacuation of British forces from New York, a triumphant moment met with widespread celebrations.

Perhaps Washington’s most revolutionary act, one that would resonate through history, came in early December 1783. After bidding farewell to his officers at Fraunces Tavern, he did something unprecedented for a victorious general: he resigned as commander-in-chief. In a final, powerful appearance before Congress, he declared his “indispensable duty to close this last solemn act of my official life, by commending the interests of our dearest country to the protection of Almighty God.” This voluntary relinquishment of power, acclaimed globally, set an enduring precedent for republican governance and civilian control of the military, as noted by historian Edward J. Larson. That same month, he was appointed president-general of the Society of the Cincinnati, a fraternity of Revolutionary War officers.

10. **The Quiet Interlude: Mount Vernon and the Call for Unity**After an astonishing eight and a half years of war, having spent merely ten days at his beloved Mount Vernon, Washington was profoundly eager to return home. Arriving on Christmas Eve, the weary hero sought the solace of private life. Professor John E. Ferling noted his delight to be “free of the bustle of a camp and the busy scenes of public life,” yet his reputation ensured Mount Vernon remained a constant destination for visitors.

His return to planter life was, however, far from idyllic. Washington rekindled pre-war interests in projects like the Great Dismal Swamp and Potomac Canal, though neither yielded dividends. To assess his Ohio Country land holdings, he embarked on a demanding 680-mile trip in 1784. He simultaneously oversaw significant remodeling at Mount Vernon, transforming it into today’s iconic mansion.

Despite outward appearances, his financial situation was precarious. Creditors paid him in depreciated wartime currency, while he faced substantial debts in taxes and wages. Mount Vernon, once thriving, had failed to turn a profit during his absence, suffering from poor crop yields due to pestilence and adverse weather. By 1787, his estate recorded its eleventh consecutive year operating at a deficit, mirroring the economic fragility of the new nation.

Ever the innovator, Washington sought to revitalize his estate, implementing new landscaping and cultivating diverse fast-growing trees and native shrubs. A fascinating development occurred in 1785 when King Charles III of Spain gifted him a stud mule; Washington, with entrepreneurial spirit, believed these mules would “revolutionize agriculture.” This period of personal struggle coincided with growing national concern. Even before officially retiring, in June 1783, Washington passionately called for a strong union, lamenting the Articles of Confederation were “a rope of sand” and fearing the nation teetered on “anarchy and confusion” and foreign intervention. He understood only a national constitution could unify the states under a robust federal structure.

11. **Forging the Framework: The Constitutional Convention of 1787**The new republic’s fragile state became clear with Shays’s Rebellion in Massachusetts in August 1786. This violent uprising, protesting economic injustice, convinced Washington a strong national constitution was essential for the United States’ survival. Many nationalists shared his apprehension, fearing the republic was descending into lawlessness.

In response, a crucial meeting in Annapolis on September 11, 1786, urged Congress to revise the Articles of Confederation. Congress, recognizing the urgency, agreed to a Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Washington, the natural choice to lead the Virginia delegation, initially hesitated, concerned about the convention’s legality. Trusted confidantes like James Madison and Henry Knox persuaded him, emphasizing his presence would lend immense legitimacy, encourage participation, and smooth ratification.

Washington’s arrival in Philadelphia on May 9, 1787, created an immediate buzz. When the convention began on May 25, Benjamin Franklin, recognizing Washington’s profound symbolic weight, nominated him to preside, a motion unanimously approved. This immediately established an air of solemn purpose for the crucial deliberations ahead.

The debates were intense and often contentious, reflecting deep divisions. Edmund Randolph introduced Madison’s Virginia Plan, a bold proposal for a new constitution and a powerful national government, which Washington enthusiastically endorsed. However, state representation was thorny, leading to a competing New Jersey Plan. On July 10, Washington confided in Alexander Hamilton, writing, “I almost despair of seeing a favorable issue to the proceedings of our convention and do therefore repent having had any agency in the business.” Despite doubts, he steadfastly lent his immense prestige, lobbying many to support ratification. The final document, incorporating elements of both plans through the Connecticut Compromise, was signed by 39 of 55 delegates on September 17, marking a pivotal moment.

Read more about: America’s Unfolding Story: A Deep Dive into the Foundational Shifts and Enduring Legacies That Reshape a Nation

12. **The First President: Setting Enduring Precedents for a New Nation**With the Constitution ratified, the young United States needed a leader commanding universal respect and trust. Unsurprisingly, George Washington was unanimously elected as the first U.S. president in both 1788 and 1792. His presidency was a period of extraordinary challenge and unparalleled institution-building, as he invented the office from scratch, shaping its powers and responsibilities for generations.

During his two terms, Washington meticulously implemented a strong, well-financed national government, laying foundational fiscal policies for stability. He remained impartial in the fierce rivalry within his cabinet between Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton, demonstrating masterful navigation of political divides. His leadership during the French Revolution was equally impactful, as he wisely proclaimed a policy of neutrality, safeguarding the fragile new nation from European conflicts, and supported the pragmatic Jay Treaty with Britain.

Washington’s legacy is most profoundly seen in the enduring precedents he established. He embodied republicanism, prioritizing civic virtue and public service. His voluntary resignation after two terms established the powerful “two-term tradition,” a norm of peaceful power transfer that defined American democracy for over a century. He even set the dignified tone with the simple yet powerful title, “Mr. President.” These were foundational principles etched into American governance.

In his seminal 1796 farewell address, Washington passionately articulated the paramount importance of national unity. He sagely warned against the perilous dangers of regionalism, partisanship, and foreign influence—a message resonating with timeless power. Though a complex figure who owned many slaves at Mount Vernon, Washington, near the end of his life, notably began opposing slavery, eventually providing in his will for their manumission, a significant, if belated, step towards justice.

Read more about: Some Analytical Insights into Ukraine’s Evolving Air Strategy: Precision Strikes, Tactical Revelations, and Geopolitical Shifts

Washington’s indelible image is an icon of American culture, memorialized from the national capital to an entire state bearing his name. Consistently ranked as one of the greatest presidents, his life story powerfully attests to the transformative impact of leadership, resilience, and an unwavering commitment to liberty and self-governance. He was not just a general or a president; he was the architect of a nation, a beacon of republicanism whose influence continues to shape the United States and inspire democratic movements globally.