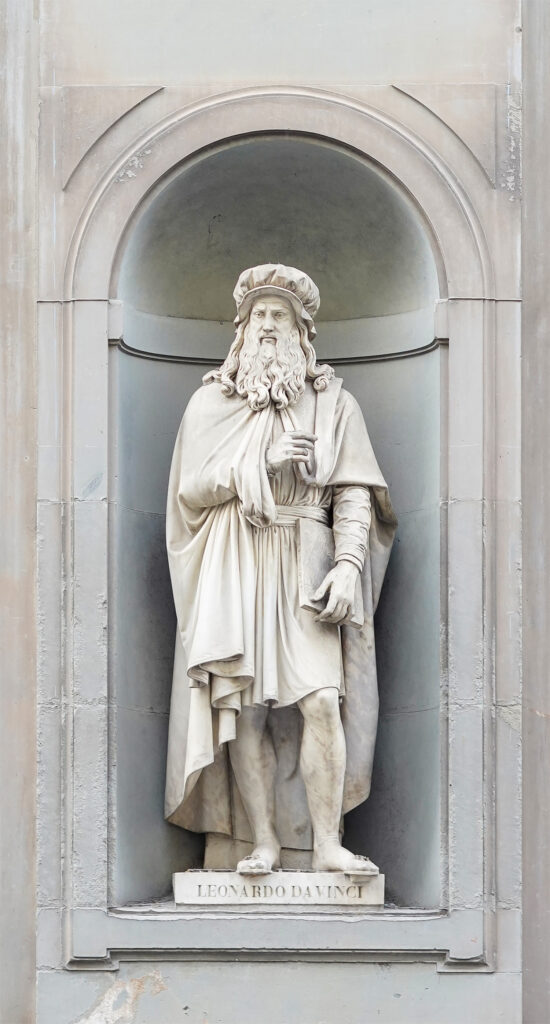

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci, born in 1452, was far more than just a painter. He was a true Italian polymath of the High Renaissance, active across an astonishing array of disciplines including painting, draughtsmanship, engineering, science, theory, sculpture, and architecture. His reputation, while initially rooted in his artistic achievements, has since expanded to encompass the vast and intricate world captured within his personal notebooks, brimming with observations and inventions that stretched the boundaries of human knowledge.

Regarded as a genius who epitomised the Renaissance humanist ideal, Leonardo’s collective works offer a contribution to later generations of artists matched only by his younger contemporary Michelangelo. His life was a testament to insatiable curiosity and a relentless pursuit of understanding, principles that guided him from his humble beginnings near Vinci to the royal courts of France. This exploration into his remarkable journey promises to unveil the multifaceted brilliance of a man whose influence continues to resonate through the ages.

Join us as we uncover 14 defining aspects of Leonardo’s extraordinary life, delving into the core elements that shaped his unparalleled mind and output. From his early education to his most challenging commissions, we aim to provide an insider’s look at the formative experiences and monumental achievements of one of history’s most fascinating figures.

1. **The Quintessential Polymath: A Mind Without Limits**Leonardo da Vinci stands as a towering figure, celebrated not merely for his artistic output but for the sheer breadth of his intellectual pursuits. He was, by every definition, a polymath, someone whose expertise spanned a remarkable range of subjects. Beyond being a master painter, he immersed himself in roles as diverse as a draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect, constantly pushing the boundaries of what one individual could achieve.

His fame might have first been secured by his brush, but it was his comprehensive notebooks that truly unveiled the depth of his genius. These pages are a treasure trove of drawings and notes on everything from anatomy and astronomy to botany, cartography, and even palaeontology. This interdisciplinary approach was not just a hobby; it was the essence of his empirical thinking, a systematic way of observing and documenting the natural world.

Leonardo’s capacity to integrate knowledge from seemingly disparate fields solidified his status as a genius, embodying the very spirit of the Renaissance humanist ideal. His collective works represent an unmatched contribution to the generations of artists and thinkers who followed, setting a standard of intellectual rigor and creative exploration that continues to inspire centuries later.

2. **Humble Beginnings: Early Life and Florentine Roots**Born on April 15, 1452, Leonardo’s origins were in, or near, the Tuscan hill town of Vinci, Italy, approximately 20 miles from Florence. His birth was notable for being out of wedlock, to Piero da Vinci, a successful Florentine legal notary, and Caterina di Meo Lippi, a woman from the lower class. This circumstance placed him in a unique social position from the outset of his life.

Following his birth, both of Leonardo’s parents married separately the very next year. Caterina, identified as Caterina Buti del Vacca, married a local artisan, while Ser Piero went on to have three subsequent marriages after the death of his first wife, Albiera Amadori. These marriages resulted in Leonardo having sixteen half-siblings, significantly younger than him, with whom he reportedly had very little contact throughout his life.

Tax records suggest that by 1457, Leonardo resided in the household of his paternal grandfather, Antonio da Vinci, though he might have spent his earliest years with his mother in Vinci. Despite his father’s successful career as a descendant of a long line of notaries, Leonardo received only a basic and informal education in vernacular writing, reading, and mathematics. It is widely believed that his prodigious artistic talents were recognized early, leading his family to focus on nurturing this specific gift.

3. **The Crucible of Craft: Apprenticeship in Verrocchio’s Workshop**Around the mid-1460s, a pivotal moment arrived when Leonardo’s family relocated to Florence, a vibrant hub of Christian Humanist thought and culture. This move opened the door to his future, as at approximately 14 years old, he became a *garzone*, a studio boy, in the prestigious workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio. Verrocchio was not just any master; he was the leading Florentine painter and sculptor of his era, and Leonardo would become his apprentice by the age of 17, remaining in training for a crucial seven years.

The workshop provided an unparalleled environment for Leonardo’s development, offering exposure to both theoretical instruction and a vast array of technical skills. He learned drafting, chemistry, metallurgy, metal working, plaster casting, and even leather working, mechanics, and woodwork. Alongside these practical crafts, he honed the essential artistic skills of drawing, painting, sculpting, and modelling, absorbing knowledge from every corner of the studio.

During this time, Leonardo was a contemporary of other emerging masters such as Botticelli, Ghirlandaio, and Perugino, all of whom were slightly older and also associated with Verrocchio’s workshop or the Medici’s Platonic Academy. Florence itself was a canvas of artistic innovation, adorned with works by figures like Donatello and Masaccio, whose realism and emotion profoundly influenced young artists. The detailed studies of perspective by Piero della Francesca and Leon Battista Alberti’s treatise *De pictura* further shaped Leonardo’s observations and artworks, laying the groundwork for his unique artistic vision.

4. **Early Strokes of Genius: The Breakthrough Florentine Works**Leonardo’s nascent talent quickly made an impression, particularly through his collaboration with his master, Verrocchio, on *The Baptism of Christ* (c. 1472–1475). According to Vasari, Leonardo painted the young angel holding Jesus’s robe with such superior skill that Verrocchio reputedly laid down his brush and never painted again – a claim, while likely apocryphal, that underscores the perceived brilliance of Leonardo’s contribution. The application of the then-new technique of oil paint to areas like the landscape and parts of Jesus’s figure, within a predominantly tempera work, clearly indicated Leonardo’s distinctive hand.

Beyond this collaborative effort, two early *Annunciation* paintings are attributed to his time in Verrocchio’s workshop, showcasing his evolving style. One, a smaller predella piece, measures 59 centimeters long and 14 centimeters high, originally intended for the base of a larger composition by Lorenzo di Credi. The other is a significantly larger work, spanning 217 centimeters in length, initially attributed to Ghirlandaio but now widely recognized as Leonardo’s own.

These *Annunciation* works reveal Leonardo’s early experimentation with traditional iconography. In the smaller painting, Mary is depicted with averted eyes and folded hands, a symbol of submission. However, in the larger piece, she is portrayed as a calm young woman, interrupted in her reading, marking her bible and raising a hand in greeting or surprise, accepting her role as the Mother of God not with resignation but with confidence. This portrayal emphasized a humanist vision of the Virgin Mary, recognizing humanity’s integral role in God’s incarnation. His *Landscape of the Arno Valley* (1473), a pen-and-ink drawing, stands as his earliest known dated work, further cementing his early mastery of observation and representation.

Read more about: Why Leonardo Da Vinci’s *Real* Love Life (and More!) Still Has Everyone Raising an Eyebrow

5. **Emerging Independence: The First Florentine Period and Ambitious Beginnings**By 1472, at the age of 20, Leonardo had achieved the status of master in the Guild of Saint Luke, the esteemed guild for artists and doctors of medicine. Despite this professional milestone, his loyalty and attachment to Verrocchio remained strong, leading him to continue collaborating and even living with his former master, even after his father established him in his own workshop. This period marked a transition towards independent commissions, yet it still underscored the profound influence of his apprenticeship.

His earliest independent commission arrived in January 1478, an altarpiece for the Chapel of Saint Bernard in Florence’s Palazzo della Signoria, signaling his full departure from Verrocchio’s studio. Further indications of his burgeoning reputation emerged in 1480, when an anonymous biographer, Anonimo Gaddiano, claimed Leonardo was living with the Medici family and frequently working in the garden of the Piazza San Marco, a vibrant intellectual hub for a Neoplatonic academy of artists, poets, and philosophers.

In March 1481, the monks of San Donato in Scopeto commissioned *The Adoration of the Magi*. However, neither of these significant initial commissions were completed. Leonardo abandoned them when he made the strategic move to offer his services to Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan. His persuasive letter to Sforza detailed his diverse capabilities in engineering and weapon design, subtly mentioning his painting skills. He even brought a silver string instrument, a lute or lyre shaped like a horse’s head, as a testament to his versatility and unique talents.

6. **Forging a Legacy: The First Milanese Period Under Sforza**Leonardo’s move to Milan marked a significant chapter, where he worked from 1482 until 1499 under the patronage of Ludovico Sforza. This period saw the creation of some of his most iconic works and grandest projects. He was commissioned to paint *The Virgin of the Rocks* for the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception and, most famously, *The Last Supper* for the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie, defining his artistic output for years.

His role extended far beyond painting. In 1490, he served as a consultant for the construction of Pavia Cathedral, where he was particularly captivated by the equestrian statue of Regisole, a subject that would later influence his own ambitious sculptural endeavors. Leonardo was also deeply involved in Sforza’s court, designing floats and pageants for special occasions, and contributing a drawing and wooden model for a competition to design the cupola for Milan Cathedral.

One of his most monumental, yet ultimately unfulfilled, projects was the *Gran Cavallo*, a colossal equestrian monument dedicated to Ludovico’s predecessor, Francesco Sforza. Intended to surpass the size of Donatello’s and Verrocchio’s famous equestrian statues, Leonardo completed a model for the horse and meticulously planned its casting. Tragically, in November 1494, Ludovico diverted the metal for cannons to defend Milan from Charles VIII of France, leaving the project unfinished. Towards the end of this period, around 1498, Leonardo and his assistants were also commissioned to create the innovative *trompe-l’œil* decoration of the Sala delle Asse in the Sforza Castle, transforming the great hall into a botanical illusion of interwoven mulberry trees.

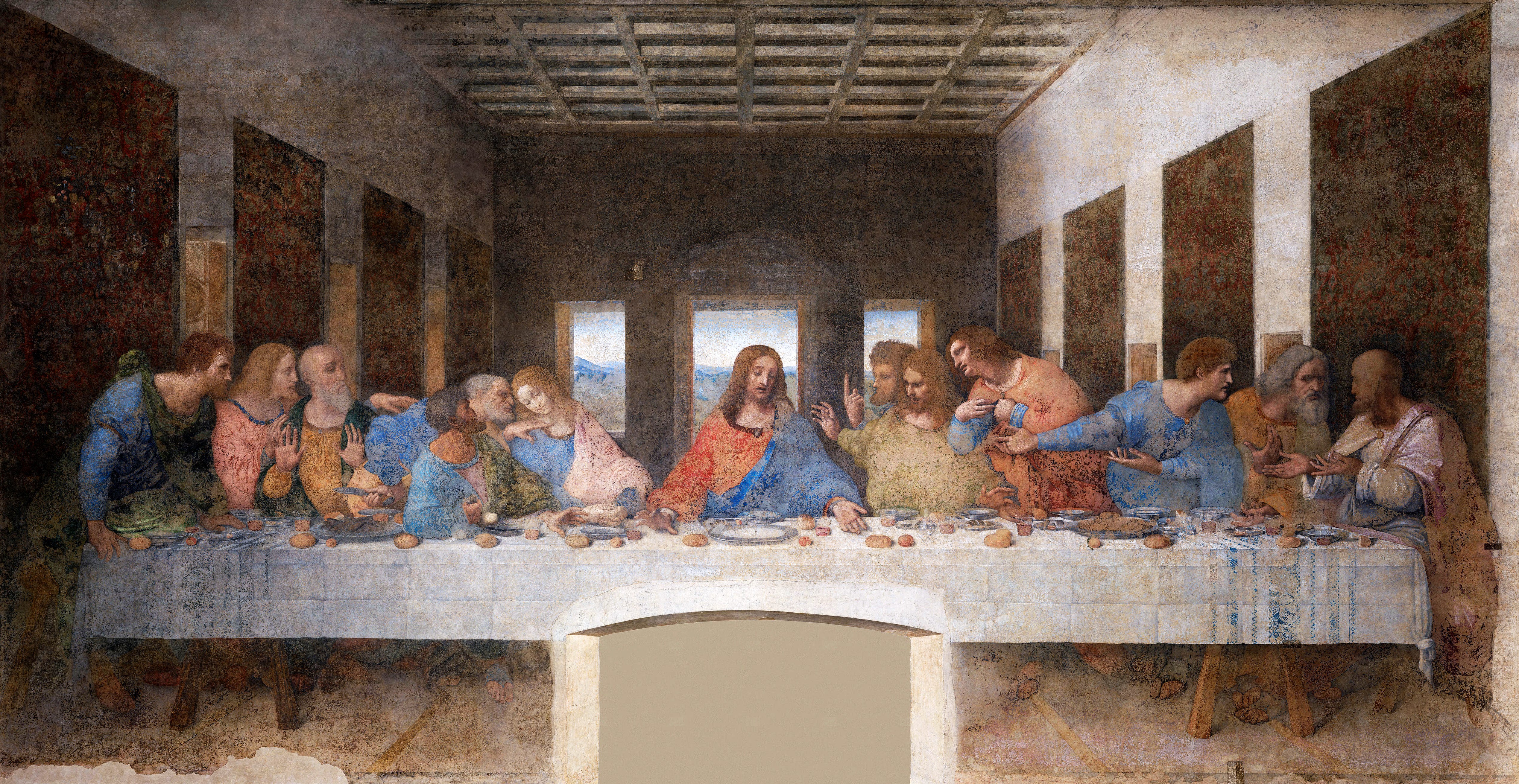

7. **The Last Supper: A Masterpiece Born of Innovation and Doomed by Experimentation**Leonardo’s *The Last Supper*, commissioned for the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria della Grazie in Milan, is arguably his most famous painting of the 1490s. It captures the intensely dramatic moment when Jesus announces to his disciples, “one of you will betray me,” immortalizing the subsequent consternation and varied emotional responses of each figure. This composition became a landmark in art history for its innovative design and profound characterization.

Eyewitness accounts offer a glimpse into Leonardo’s unusual working methods. The writer Matteo Bandello observed that some days Leonardo would paint tirelessly from dawn till dusk, yet then leave the work untouched for three or four days at a time. Such erratic patterns were beyond the comprehension of the convent’s prior, who hounded Leonardo until Ludovico Sforza had to intervene. Vasari even recounts how Leonardo, troubled by the challenge of depicting the faces of Christ and the traitor Judas, lightheartedly suggested using the prior as his model.

Despite being acclaimed as a masterpiece, the painting faced an immediate and tragic flaw. Instead of using the reliable fresco technique, Leonardo experimented with tempera over a ground primarily composed of gesso. This unconventional method, designed to allow for slow, deliberate work typical of oil painting, unfortunately made the surface highly susceptible to mould and flaking. Consequently, within just a hundred years of its completion, the painting was described by one viewer as “completely ruined,” a testament to the risks inherent in his relentless pursuit of innovation, though it remains one of the most reproduced works of art to this day. There is no denying the profound impact it has had on subsequent generations of artists and its enduring cultural significance.

8. **The Florentine Return: Masterpieces and Unfinished Visions**Following the French overthrow of Ludovico Sforza in 1500, Leonardo’s journey led him back to Florence, but not before a brief, impactful stop in Venice. There, he applied his extraordinary intellect as a military architect and engineer, conceptualizing defenses against potential naval assaults. Upon his arrival in Florence, he was welcomed by the Servite monks at the monastery of Santissima Annunziata, who provided him with a workshop. It was during this period that, according to Vasari, he created the renowned cartoon of *The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and Saint John the Baptist*, a work that drew immense public admiration, with crowds flocking to see it as if attending a grand festival.

His path soon diverged into new, politically charged territories. In 1502, Leonardo entered the service of Cesare Borgia, the ambitious son of Pope Alexander VI. As Borgia’s chief military architect and engineer, Leonardo traveled extensively throughout Italy with his patron, creating detailed town plans like that of Imola and a strategic map of the Chiana Valley in Tuscany. These projects showcased his practical application of cartography and civil engineering, notably his scheme to construct a dam from the sea to Florence, designed to maintain a consistent water supply for a canal throughout all seasons, a testament to his foresight in infrastructure.

Leonardo’s return to Florence by early 1503 saw him rejoin the Guild of Saint Luke, signaling a re-engagement with his artistic roots. This period is most famously marked by the genesis of his iconic *Mona Lisa*. Commencing work on the portrait of Lisa del Giocondo, he would continue to refine this masterpiece for many years. Simultaneously, he took on a monumental civic commission: designing and painting a mural of *The Battle of Anghiari* for the Salone dei Cinquecento in the Palazzo Vecchio, a companion piece to Michelangelo’s *The Battle of Cascina*. This ambitious undertaking, depicting a dynamic cavalry battle, sadly deteriorated rapidly and is now known primarily through copies, including one by Rubens, yet its influence on subsequent art history remains profound.

9. **Beyond the Canvas: Leonardo’s Scientific and Engineering Legacy**While his paintings captivate the world, Leonardo’s genius extended profoundly into the realms of science and engineering, often foreshadowing discoveries centuries ahead of his time. He was a technological visionary, conceptualizing innovations that ranged from intricate flying machines and a type of armored fighting vehicle to concentrated solar power. His notebooks reveal designs for a ratio machine, considered a precursor to an adding machine, and even the double hull, showcasing his deep understanding of mechanics and physics.

Remarkably, the feasibility of many of his grander designs was limited by the nascent state of metallurgy and engineering during the Renaissance. Modern scientific approaches simply had not yet evolved to match his theoretical ambitions. Consequently, relatively few of his most complex inventions were constructed or even practical during his lifetime. Yet, his ingenuity found more immediate, albeit unheralded, applications in smaller, practical inventions, such as an automated bobbin winder and a machine designed to test the tensile strength of wire, silently entering the manufacturing world.

Leonardo made substantial, groundbreaking discoveries across a multitude of scientific disciplines. His meticulous dissections led to significant advancements in anatomy, capturing the intricate details of the human body with unparalleled accuracy. He delved into civil engineering, hydrodynamics, geology, optics, and tribology, producing observations and theories that were profoundly ahead of his era. However, his decision not to publish these vast findings meant that they had little to no direct influence on subsequent scientific development, leaving generations to rediscover what he had already conceptualized and documented in his private journals.

10. **Rome and the Vatican: Shifting Sands of Patronage**In March 1513, with Lorenzo de’ Medici’s son Giovanni ascending to the papacy as Leo X, Leonardo made his way to Rome that September. He was received by the pope’s brother, Giuliano, and for the next three years, until 1516, much of his time was spent living in the Belvedere Courtyard within the Apostolic Palace – a period when both Michelangelo and Raphael were also actively working there. Despite the prestigious surroundings, Leonardo’s experience in Rome proved to be a mix of curiosity and frustration.

The pontifical court provided Leonardo with an allowance of 33 ducats a month, a testament to his esteemed position. He engaged in intriguing, if somewhat peculiar, pursuits, such as decorating a lizard with scales dipped in quicksilver, as Vasari recounts. The Pope even offered him a painting commission, the subject of which remains unknown, but it was abruptly canceled when Leonardo became engrossed in developing a new type of varnish, a testament to his relentless experimentation, even at the cost of fulfilling direct commissions.

During his time in Rome, Leonardo also faced personal challenges, suffering from an illness that may have been the first of several strokes leading to his eventual demise. Undeterred, he continued his scientific endeavors, practicing botany in the Vatican Gardens and undertaking a commission to draw up plans for the Pope’s proposed draining of the Pontine Marshes. He also continued his anatomical dissections, making notes for a treatise on vocal cords, which he hoped would regain papal favor, but ultimately without success. This period highlights his persistent intellectual curiosity despite physical setbacks and challenges in securing consistent artistic commissions.

11. **The French Sunset: Last Years at Clos Lucé**The political landscape shifted again in October 1515 when King Francis I of France recaptured Milan. A subsequent invitation from the French king marked the final chapter of Leonardo’s remarkable life. On March 21, 1516, the French ambassador to the Holy See received instructions from King Francis I, expressing the king’s eager anticipation of Leonardo’s arrival and reassuring the artist that he would be warmly received by both the king and his mother, Louise of Savoy. Leonardo subsequently entered Francis’s service later that year, embarking on a new life in France.

Francis I provided Leonardo with the picturesque manor house of Clos Lucé, conveniently located near the king’s own residence at the royal Château d’Amboise. Leonardo was frequently visited by the young monarch, who held him in high esteem and engaged him in various projects. Among these were plans for an immense castle town that the King envisioned erecting at Romorantin, showcasing Leonardo’s continuing architectural ambitions. He also famously crafted a mechanical lion, an impressive spectacle that, during a pageant, walked towards the King and, upon being struck by a wand, revealed a cluster of lilies, symbolizing the French monarchy. These grand gestures underscored the king’s admiration for Leonardo’s unique blend of artistry and ingenuity.

Throughout these final years, Leonardo was accompanied by his cherished friend and apprentice, Francesco Melzi, and enjoyed a generous pension totaling 10,000 scudi. Melzi, a Lombard aristocrat, became not only his closest confidant but also his principal heir and executor. It was during this period that Melzi drew a poignant portrait of Leonardo, one of only a few known from his lifetime. Later records, including a drawing by Giovanni Ambrogio Figino and an account from a visit by Louis d’Aragon in 1517, sadly confirm that Leonardo suffered from paralysis in his right hand at the age of 65. This condition may well explain why significant works, such as the *Mona Lisa*, remained in various stages of completion. Despite his ailments, he continued to work to some capacity until his final illness and eventual confinement to bed.

12. **The Private Leonardo: Relationships, Speculation, and a Love for Life**Despite the thousands of pages filled with his intellectual pursuits, Leonardo’s personal notebooks offer surprisingly few direct references to his private life, leaving much to conjecture. Within his lifetime, his remarkable powers of invention, coupled with his “great physical beauty” and “infinite grace,” as described by Vasari, sparked considerable curiosity. One endearing aspect of his character was his profound love for animals, which likely extended to vegetarianism, and his noted habit of purchasing caged birds merely to set them free.

Leonardo cultivated many notable friendships, including with the mathematician Luca Pacioli, with whom he collaborated on the influential book *Divina proportione* in the 1490s. His close relationships with women were notably platonic, most famously with Cecilia Gallerani and the Este sisters, Beatrice and Isabella. While on a journey through Mantua, he created a portrait of Isabella, which, though now lost, suggests a bond of mutual respect and admiration rather than romance.

However, it is his uality that has been the subject of enduring satire, analysis, and speculation, a trend that began in the mid-16th century and was notably revived by Sigmund Freud. His most intimate relationships appear to have been with his pupils, Salaì and Francesco Melzi. Melzi, in his letter informing Leonardo’s brothers of his death, described Leonardo’s feelings for his pupils as both loving and passionate. Since the 16th century, these relationships have been interpreted by some as sexual or erotic, with modern biographers like Walter Isaacson explicitly stating his opinion that relations with Salaì were intimate and homosexual. Historical records from 1476 show Leonardo and three other young men were charged with sodomy involving a known male prostitute, though the charges were dismissed for lack of evidence, leading to speculation that Medici family influence played a role. This ongoing discussion frequently explores how his presumed homosexuality might have influenced the androgyny and eroticism seen in works like *Saint John the Baptist*, *Bacchus*, and various erotic drawings.

13. **The Painter’s Secret: Decoding Leonardo’s Revolutionary Techniques**For nearly four centuries, Leonardo’s fame rested predominantly on his astounding achievements as a painter, a testament to the revolutionary quality of his limited body of work. His authenticated or attributed paintings are not merely masterpieces but foundational texts in the history of Western art, celebrated for their myriad qualities and endlessly debated by connoisseurs. By the 1490s, he was already being hailed as a “Divine” painter, a title reflecting the awe his innovative approach inspired.

The unique qualities that elevate Leonardo’s work include his groundbreaking techniques for applying paint, which diverged significantly from the practices of his contemporaries. This was underpinned by his comprehensive and detailed knowledge of anatomy, light, botany, and geology – disciplines he studied rigorously and integrated seamlessly into his artistic vision. His profound interest in physiognomy allowed him to capture the subtle nuances of human emotion through expression and gesture, imbuing his figures with an unprecedented psychological depth.

Crucially, Leonardo was a master of innovative figurative composition, arranging human forms in ways that were dynamic and expressive, moving beyond rigid conventions. His use of subtle gradation of tone, famously known as *sfumato*, or “Leonardo’s smoke,” created a soft, almost imperceptible blurring of lines and colors. This technique, particularly evident in the enigmatic smile of the *Mona Lisa* and the serene complexity of *The Virgin of the Rocks*, allowed for a naturalistic rendering of atmosphere and form that profoundly influenced future generations, making his brushstrokes indistinguishable and lending his works a living, breathing quality that Vasari noted as being “more divine than human.”

14. **A Legacy Etched in Eternity: The Undying Influence of a Polymath**Leonardo da Vinci’s life drew to a close at Clos Lucé on May 2, 1519, at the age of 67, likely due to a stroke. His close friendship with King Francis I was a poignant detail of his final years, though the popular account of the King holding Leonardo’s head as he died is largely considered legendary. On his deathbed, Vasari recounts, Leonardo lamented that he “had offended against God and men by failing to practice his art as he should have done,” a reflection of his relentless pursuit of perfection and perhaps the weight of his uncompleted projects. In accordance with his will, sixty beggars followed his casket, a humble tribute to a man of monumental intellect.

His passing marked not an end, but a transition to an enduring legacy. Francesco Melzi, his devoted apprentice, was the principal heir, receiving Leonardo’s paintings, tools, library, and personal effects, ensuring the preservation of his monumental body of work and intellectual property. His other long-time companion, Salaì, and his servant Baptista de Vilanis, each received a portion of his vineyards, while his brothers received land and his serving woman a fur-lined cloak, demonstrating Leonardo’s thoughtful consideration for those in his household. Twenty years after his death, the goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini recorded King Francis I’s profound declaration: “There had never been another man born in the world who knew as much as Leonardo, not so much about painting, sculpture and architecture, as that he was a very great philosopher.”

Indeed, since his death, there has never been a period when Leonardo’s achievements, diverse interests, personal life, and empirical thinking have failed to incite interest and admiration. He is justly identified as one of the greatest painters in Western art history and is frequently credited as the founder of the High Renaissance. Despite the unfortunate loss of many works and fewer than 25 attributed major paintings—many unfinished—he shaped some of the most influential images in the Western canon. The *Mona Lisa* reigns as the world’s most famous individual painting, *The Last Supper* is the most reproduced religious work of all time, and his *Vitruvian Man* drawing stands as a global cultural icon. The recent record-breaking sale of *Salvator Mundi* in 2017 for US$450.3 million, attributed in whole or part to Leonardo, further underscores his unparalleled and timeless significance in the art world and beyond. His multifaceted brilliance continues to inspire, educate, and awe, cementing his place as an eternal symbol of human potential.