America, a nation synonymous with resilience, innovation, and an ever-evolving spirit, holds a captivating narrative woven from centuries of diverse experiences. It’s a story of pioneering spirits, transformative ideas, and an unwavering pursuit of progress that has shaped not just a continent, but the world. As we embark on this journey, we’ll uncover the pivotal moments and enduring characteristics that define this remarkable federal republic.

This isn’t just a recount of dates and events; it’s an exploration of the forces that forged a diverse collection of peoples and lands into a unified powerhouse. From the ancient civilizations that first graced its landscapes to the complex dance of democracy and economic dynamism, America’s path has been one of constant reinvention and profound impact. The challenges faced, the victories celebrated, and the lessons learned all contribute to a truly inspiring saga.

Join us as we navigate the rich tapestry of the United States, shedding light on its profound origins, the momentous struggles for liberty, the sweeping changes that defined its growth, and the foundational elements that continue to make it a country unlike any other. Our journey begins at the very dawn of its existence, tracing the steps of its earliest inhabitants and the first whispers of European arrival.

1. America’s Earliest Chapters: Indigenous Peoples and European Arrivals

Long before any European sails touched its shores, North America was a vibrant mosaic of Indigenous cultures, thriving and evolving for over 12,000 years. Paleo-Indians, migrating from North Asia, established diverse civilizations across the continent. Among them, the Clovis culture emerged around 11,000 BC, widely considered the first widespread culture in the Americas, laying the groundwork for more complex societies to follow.

Over millennia, these Indigenous North American cultures grew increasingly sophisticated. The Mississippian cultures flourished in the midwestern, eastern, and southern regions, developing agriculture, intricate architecture, and complex social structures. In the Great Lakes region and along the Eastern Seaboard, the Algonquian peoples built their communities, while the Hohokam culture and Ancestral Puebloans established enduring settlements in the Southwest, each contributing uniquely to the continent’s rich heritage.

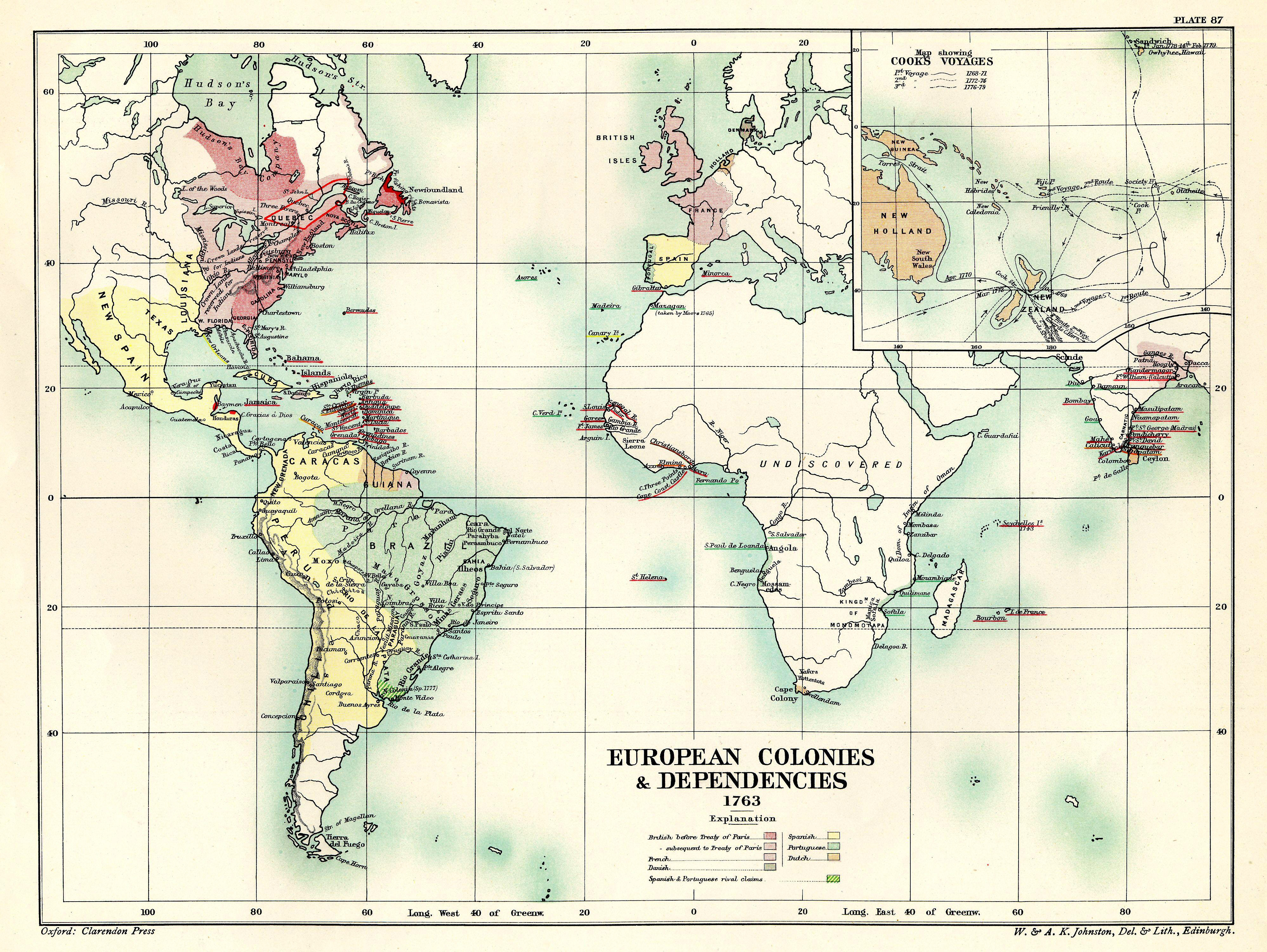

The arrival of Europeans marked a dramatic turning point. Christopher Columbus’s explorations for Spain began in the Caribbean in 1492, soon leading to Spanish settlements and missions stretching from what are now Puerto Rico and Florida to New Mexico and California. Spanish Florida, chartered in 1513, became the first European colony in what is now the continental United States, though a permanent town, Saint Augustine, wasn’t founded until 1565 after several earlier attempts failed.

Other European powers quickly followed. France established settlements along the Great Lakes, the Mississippi River, and the Gulf of Mexico, with New Orleans becoming a significant permanent hub in 1718. Early European colonies also included the thriving Dutch colony of New Netherland, settled in 1626 and the precursor to present-day New York, and the small Swedish colony of New Sweden, established in 1638 in what would later become Delaware.

British colonization of the East Coast began with the Virginia Colony in 1607 and the Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts in 1620. These early settlements were crucial, with documents like the Mayflower Compact in Massachusetts and the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut establishing vital precedents for local representative self-governance and constitutionalism. These ideas would profoundly influence the development of the American colonies, even as relations with Native Americans ranged from cooperation and trade to brutal warfare and forced assimilation, and the Atlantic slave trade began trafficking enslaved Africans.

2. The Spark of Liberty: Revolution and the Birth of a Republic

By the mid-18th century, the thirteen British colonies along the East Coast had developed a strong sense of self-governance, fostered by their distance from Britain and local elections open to most white male property owners. The population grew rapidly, and a series of Christian revivals known as the First Great Awakening further fueled colonial interest in guaranteed religious liberty, laying spiritual groundwork for future independence.

Following their costly victory in the French and Indian War, Britain began to assert greater control over colonial affairs, leading to mounting political resistance. A primary grievance was the denial of their rights as Englishmen, particularly the right to representation in the British government that was imposing new taxes. In response, the First Continental Congress met in 1774, passing the Continental Association — a colonial boycott of British goods that proved remarkably effective.

Tensions escalated dramatically when a British attempt to disarm the colonists sparked the Battles of Lexington and Concord in 1775, igniting the American Revolutionary War. At the Second Continental Congress, George Washington was appointed commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, and a committee, including Thomas Jefferson, was tasked with drafting the Declaration of Independence. This groundbreaking document, adopted on July 4, 1776, formally declared the colonies’ intention to create an independent nation.

The political values that underpinned the American Revolution were revolutionary for their time: liberty, inalienable individual rights, and the sovereignty of the people. They championed republicanism, firmly rejecting monarchy, aristocracy, and any form of hereditary political power, while emphasizing civic virtue and vilifying political corruption. The Founding Fathers, including Washington, Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and James Madison, drew inspiration from Classical, Renaissance, and Enlightenment philosophies.

After the British surrender at the siege of Yorktown in 1781, American sovereignty was internationally recognized by the Treaty of Paris (1783). This landmark agreement granted the U.S. vast territory stretching west to the Mississippi River, north to present-day Canada, and south to Spanish Florida. To overcome the limitations of the Articles of Confederation, the U.S. Constitution was drafted in 1787 and went into effect in 1789, establishing a federal republic with three separate branches and a system of checks and balances. George Washington was elected the first president, and the Bill of Rights was adopted in 1791, solidifying fundamental freedoms and setting precedents for a peaceful transfer of power.

3. A Nation Forged in Expansion and Division: Westward Journey and Civil War

As the young republic found its footing, American settlers began a fervent expansion westward in the late 18th century, driven by a powerful sense of manifest destiny. This ambition reshaped the nation’s geography, notably with the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 from France, an acquisition that nearly doubled the territory of the United States. Further asserting its boundaries, the War of 1812, fought to a draw with Britain, helped solidify American sovereignty, while Spain ceded Florida and its Gulf Coast territory in 1819.

However, this grand expansion brought with it a profound internal conflict: the question of slavery. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 attempted to balance the desires of northern states to prevent slavery’s expansion into new territories with southern states’ push to extend it. This compromise admitted Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state, crucially prohibiting slavery in all other Louisiana Purchase lands north of the 36°30′ parallel.

As settlers pushed deeper into Native American territories, the federal government pursued policies of Indian removal or assimilation. A key policy of President Andrew Jackson, the Indian Removal Act of 1830, led to the tragic Trail of Tears between 1830 and 1850. During this period, an estimated 60,000 Native Americans living east of the Mississippi River were forcibly removed and displaced to lands far to the west, resulting in the deaths of 13,200 to 16,700 people during their forced march. This influx, alongside settler expansion, fueled further American Indian Wars west of the Mississippi.

The mid-19th century saw continued territorial gains: the United States annexed the Republic of Texas in 1845, and the 1846 Oregon Treaty secured U.S. control of the present-day American Northwest. Dispute with Mexico over Texas then escalated into the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). Following a U.S. victory, Mexico recognized American sovereignty over vast new territories, including Texas, New Mexico, and California, as well as the future states of Nevada, Colorado, and Utah, in the 1848 Mexican Cession. The California Gold Rush of 1848–1849 spurred a massive migration to the Pacific coast, leading to further violent confrontations with Native populations, including the California genocide that lasted into the mid-1870s.

The deepening sectional conflict over slavery reached a breaking point in the 1850s. While northern states had begun to prohibit slavery, its profitability in the South, boosted by inventions like the cotton gin, solidified support among southern elites. National legislation like the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, mandating the return of escaped slaves, and the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854, which gutted anti-slavery requirements, inflamed tensions. The Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision of 1857, declaring the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional, further exacerbated these divisions, culminating in the outbreak of the American Civil War (1861–1865).

4. From Reconstruction to Global Power: Industry, Immigration, and World Wars

The American Civil War, a harrowing chapter of national division, ended with a Union victory in 1865, leading to the reunification of the states and the national abolition of slavery. This momentous change was codified by the Reconstruction Amendments to the Constitution: the 13th abolished slavery, the 14th promised equal protection under the law for all persons, and the 15th prohibited discrimination in voting based on race or previous enslavement. For a brief decade, African Americans took an active political role in the former Confederate states, marking a significant, albeit short-lived, period of progress.

In the decades that followed, America underwent a period of unprecedented national development. Transcontinental infrastructure, including telegraph lines and railroads, spurred growth and connected the vast American frontier. The Homestead Acts further accelerated this expansion, granting nearly 10 percent of the total land area of the United States to some 1.6 million homesteaders, fostering westward migration and settlement.

This era also witnessed a massive influx of immigrants, with an unprecedented 24.4 million arriving from Europe between 1865 and 1917. The Port of New York became a bustling gateway, and cities like New York, Chicago, and others on the East Coast and Midwest became home to large Jewish, Irish, Italian, and German populations, enriching the nation’s cultural fabric. Concurrently, the Great Migration saw millions of African Americans leave the rural South for urban areas in the North, seeking better opportunities and an escape from racial oppression.

However, the promise of Reconstruction was tragically curtailed. The Compromise of 1877, which resolved a presidential electoral crisis, led to the withdrawal of federal troops from the South. This immediately empowered the “Redeemers,” who quickly re-established white supremacist control over southern politics. This ushered in the “nadir of American race relations,” characterized by rampant overt racism, Jim Crow laws enforcing segregation, sundown towns, and Supreme Court decisions like *Plessy v. Ferguson* that effectively nullified the Reconstruction Amendments, further reinforced by federal policies like redlining.

Despite these social challenges, an explosion of technological advancement, coupled with the exploitation of cheap immigrant labor, fueled rapid economic expansion in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The United States surpassed the combined economies of England, France, and Germany, becoming a pioneer in industries like railroads, petroleum, steel, and automotive manufacturing. While this created immense wealth for tycoons and corporations through trusts and monopolies, it also led to significant increases in economic inequality and social unrest, giving rise to powerful labor unions and inspiring the Progressive Era’s reforms. The nation also expanded its territorial reach, acquiring Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

The early 20th century saw America step onto the global stage. The U.S. entered World War I in 1917, helping to turn the tide against the Central Powers. Domestically, 1920 marked a monumental victory for women’s rights with the constitutional amendment granting nationwide women’s suffrage. The roaring twenties gave way to the devastating Wall Street Crash of 1929, triggering the Great Depression. President Franklin D. Roosevelt responded with the transformative New Deal, a series of sweeping recovery programs, employment relief projects, and financial reforms that redefined the government’s role in society.

The nation’s resolve was tested again by World War II. Initially neutral, the U.S. began supplying war materiel to the Allies and formally entered the war after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. The U.S. played a decisive role, developing and ultimately deploying the first nuclear weapons against Japanese cities in August 1945, which brought the war to a swift conclusion. Emerging relatively unscathed from the global conflict, the United States found itself with unparalleled economic power and international political influence, poised to shape the post-war world.

Read more about: America’s Unfolding Story: A Deep Dive into the Foundational Shifts and Enduring Legacies That Reshape a Nation

5. The Cold War Era and Social Transformation: Superpowers and Civil Rights

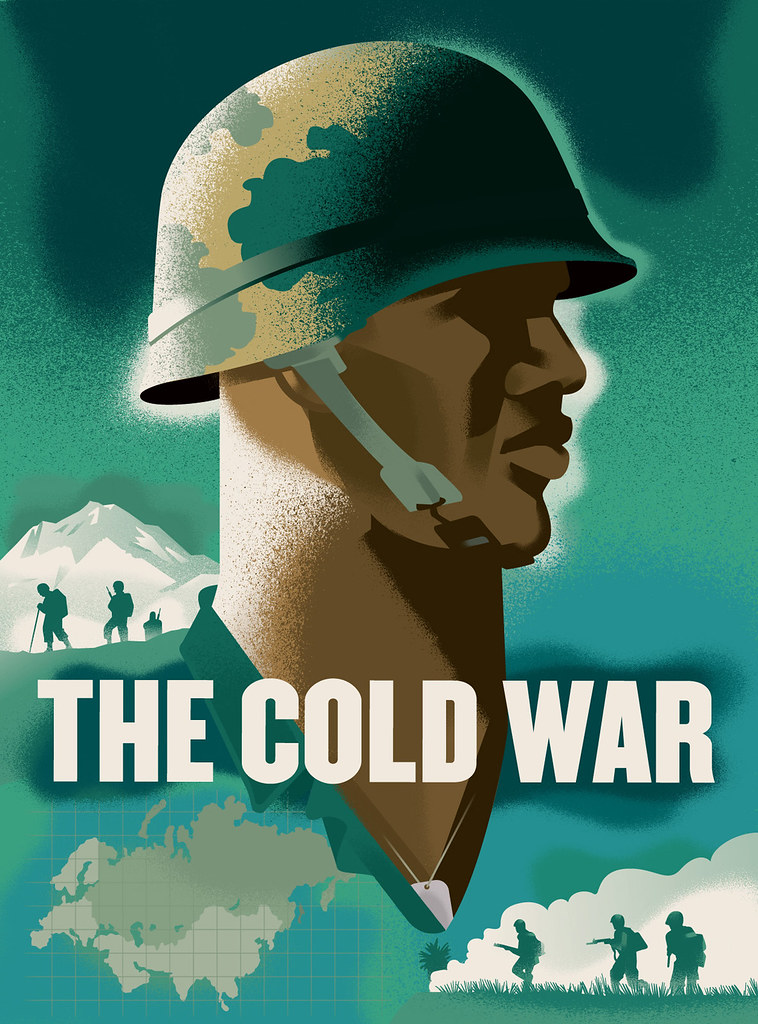

The aftermath of World War II profoundly reshaped the global landscape, leaving the United States and the Soviet Union as two dominant superpowers, each commanding vast political, military, and economic spheres of influence. This unprecedented bipolarity quickly escalated into the Cold War, a period defined by intense geopolitical tensions, ideological rivalry, and an intricate dance of international strategy that would last for decades.

In this new global contest, the U.S. adopted a policy of containment, aiming to limit the Soviet Union’s expansion and influence around the world. This often involved engaging in regime change against governments perceived to be aligned with the Soviets and fiercely competing in technological and military arenas, famously culminating in the Space Race. This competition saw humanity achieve one of its most incredible feats: the first crewed Moon landing in 1969, a monumental American triumph.

Domestically, the U.S. experienced a period of remarkable economic growth, significant urbanization, and a substantial population boom following World War II. This prosperity, however, starkly highlighted persistent inequalities, giving rise to the powerful civil rights movement. Led by visionary figures like Martin Luther King Jr., the movement gained significant momentum in the early 1960s, challenging systemic racial discrimination and advocating for equal rights for all Americans.

Responding to the fervent calls for change, President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration launched the ambitious Great Society plan. This initiative resulted in groundbreaking and broad-reaching laws, policies, and a constitutional amendment specifically designed to counteract some of the worst effects of lingering institutional racism and poverty, aiming to build a more equitable and just society for everyone.

Alongside the civil rights struggle, the counterculture movement brought about significant social changes across the U.S. This period saw the liberalization of attitudes toward recreational drug use and uality, challenging traditional norms. It also fostered open defiance of the military draft, ultimately leading to the end of conscription in 1973, and widespread opposition to U.S. intervention in Vietnam, which concluded with the complete withdrawal of American forces in 1975. Simultaneously, a significant societal shift in the roles of women led to a large increase in female paid labor participation during the 1970s, with the majority of American women aged 16 and older employed by 1985.

6. Contemporary America: Technological Frontiers and Evolving Challenges

As the Cold War drew to a close with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, leaving the United States as the world’s sole superpower, a new chapter unfolded for the nation. The 1990s heralded a remarkable period of economic expansion, marking the longest such growth recorded in American history. This era also saw a dramatic decline in U.S. crime rates, creating an atmosphere of renewed optimism and domestic stability. It was a time when the nation fully embraced its global influence, solidifying the concept of the “American Century” as the U.S. continued to dominate international political, cultural, economic, and military affairs.

This period was fundamentally shaped by an explosion of technological innovation that transformed daily life and industry. Groundbreaking advancements such as the World Wide Web, the continuous evolution of the Pentium microprocessor, and the development of rechargeable lithium-ion batteries became household staples, revolutionizing communication and personal computing. The scientific community also pushed boundaries with the first gene therapy trial and early experiments in cloning, hinting at a future brimming with medical and biological possibilities.

The spirit of scientific inquiry was further exemplified by the formal launch of the Human Genome Project in 1990, a monumental endeavor to map the entirety of human DNA. This decade also saw the financial world adapt to the digital age, with Nasdaq making history in 1998 as the first stock market in the United States to trade online. These innovations not only spurred economic growth but also fundamentally reshaped how Americans lived, worked, and interacted with the world.

However, the dawn of the 21st century brought unforeseen challenges. In 1991, an American-led international coalition successfully expelled an Iraqi invasion force from Kuwait in the Gulf War, demonstrating the nation’s commitment to global security. Yet, the tranquility of the economic boom was shattered by the September 11 attacks in 2001, a horrific act by the pan-Islamist militant organization al-Qaeda that profoundly impacted the nation. This tragic event initiated the “war on terror” and led to significant military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq, marking a somber pivot in American foreign policy.

Domestically, the nation grappled with economic instability as a housing bubble culminated in 2007, triggering the Great Recession—the largest economic contraction since the Great Depression. In the 2010s and early 2020s, the United States has also faced increased political polarization and democratic backsliding, culminating in events like the January 2021 Capitol attack. This period continues to test America’s resilience, highlighting the ongoing effort to balance progress with the preservation of its foundational democratic principles.

7. A Land of Grand Diversity: Geography, Climate, and Conservation

The United States truly stands as a testament to geographical grandeur and diversity, ranking as the world’s third-largest country by total area, surpassed only by Russia and Canada. Its vast expanse encompasses the 48 contiguous states, the federal capital district of Washington, D.C., the semi-exclave of Alaska in the northwest, and the volcanic archipelago of Hawaii nestled in the Pacific Ocean. Beyond its continental and insular states, the U.S. also asserts sovereignty over five major island territories and various uninhabited islands across Oceania and the Caribbean, making it a truly global geographical entity.

From the Atlantic seaboard, a coastal plain gracefully transitions into the inland forests and rolling hills of the Piedmont plateau region. Venture further west, and the majestic Appalachian Mountains and the Adirondack Massif rise, forming a natural divide between the East Coast and the expansive Great Lakes and fertile grasslands of the Midwest. The country is bisected by the mighty Mississippi River System, the world’s fourth-longest, flowing predominantly north–south through its heart, feeding the flat and incredibly fertile prairie of the Great Plains, which is occasionally interrupted by highlands in the southeast.

Moving westward from the Great Plains, the dramatic Rocky Mountains stretch across the country, their peaks soaring over 14,000 feet in Colorado, creating breathtaking vistas. Beneath this rugged beauty lies geological wonders like the supervolcano of the Yellowstone Caldera, the continent’s largest volcanic feature. Further still, the landscape transforms into the stark beauty of the rocky Great Basin and the vast Chihuahuan, Sonoran, and Mojave deserts, each with its unique character. The Colorado River has carved another iconic landmark in the northwest corner of Arizona: the Grand Canyon, a steep-sided canyon celebrated for its overwhelming visual size and intricate, colorful landscape, drawing countless admirers.

As one approaches the Pacific coast, the impressive Cascade and Sierra Nevada mountain ranges dominate the horizon. California alone holds the unique distinction of hosting both the lowest and highest points in the contiguous United States, separated by a mere 84 miles, showcasing incredible topographical extremes. Far to the north, Alaska proudly boasts Denali, also known as Mount McKinley, soaring to an elevation of 20,310 feet, making it the highest peak not only in the country but on the entire continent. Active volcanoes are a common sight across Alaska’s Alexander and Aleutian Islands, while Hawaii, entirely outside North America, offers stunning volcanic islands that are physiographically and ethnologically part of the Polynesian subregion of Oceania.

With such immense size and geographic variety, the United States naturally hosts a mosaic of climate types. East of the 100th meridian, the climate shifts from humid continental in the north to humid subtropical in the south, creating distinct seasonal experiences. The western Great Plains are semi-arid, while many mountainous areas of the American West experience an alpine climate. The Southwest is characterized by arid conditions, coastal California enjoys a Mediterranean climate, and the coastal regions of Oregon, Washington, and southern Alaska are oceanic. Hawaii, the southern tip of Florida, and U.S. territories in the Caribbean and Pacific are bathed in tropical warmth. This incredible climatic range, however, comes with its challenges; the U.S. receives more high-impact extreme weather incidents than any other country, with Gulf states prone to hurricanes and most of the world’s tornadoes occurring in Tornado Alley. Climate change in the 21st century has amplified these events, with more frequent heat waves and persistent, severe droughts in the Southwest, reminding us of the urgent need for environmental stewardship. The U.S. is also one of 17 megadiverse countries, home to about 17,000 vascular plant species in the contiguous states and Alaska, and over 1,800 flowering plant species in Hawaii, many of which are endemic. The country shelters 428 mammal species, 784 birds, 311 reptiles, 295 amphibians, and approximately 91,000 insect species. To protect this natural heritage, 63 national parks and hundreds of other federally managed monuments, forests, and wilderness areas are administered by agencies like the National Park Service. About 28% of the country’s land is publicly owned and federally managed, primarily in the Western States, with much of it protected under the Wilderness Act of 1964 and the Endangered Species Act of 1973, reflecting a deep commitment to preserving its unparalleled biodiversity.

8. The Pillars of Governance: America’s Federal Republic

The United States is a distinctive federal republic composed of 50 states and its federal capital district, Washington, D.C. It also asserts sovereignty over five unincorporated territories and several uninhabited island possessions, creating a complex and extensive political entity. As the world’s oldest surviving federation, its presidential system of national government has profoundly influenced global governance, with many newly independent states worldwide adopting elements of its structure following their decolonization. At the heart of this intricate system lies the U.S. Constitution, which serves as the country’s supreme legal document and the bedrock of its democratic principles. Most scholars accurately describe the United States as a liberal democracy, embodying ideals of individual liberty and representative government.

The federal government, with all three of its branches headquartered in Washington, D.C., is meticulously designed to operate under a robust system of checks and balances. This separation of powers, a foundational principle enshrined in the Constitution, is intended to prevent any single branch from becoming overly dominant, ensuring a balance of authority and safeguarding against potential abuses. This intricate dance between legislative, executive, and judicial powers is crucial to the nation’s stability and its commitment to democratic governance.

Central to this structure is the U.S. Congress, a bicameral legislature comprising the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Senate consists of 100 members, with two residents from each state, elected by that state’s voters for a six-year term, providing equal representation regardless of population size. The House of Representatives, conversely, has 435 members, each elected for a two-year term by the constituency of a specific congressional district. These district boundaries are determined by each state’s legislature, with the critical requirement that every U.S. congressional district must be of equivalent population, ensuring fair representation.

Beyond the national government, federalism is a defining characteristic, granting substantial autonomy to the 50 states, allowing them to tailor laws and policies to their unique needs while remaining part of a unified nation. Furthermore, 574 Native American tribes possess sovereignty rights, alongside 326 Native American reservations, acknowledging their distinct governmental status within the broader federal framework. Since the 1850s, American politics have been largely dominated by the Democratic and Republican parties, reflecting a deeply ingrained two-party system. These political dynamics, along with American values, are deeply rooted in a democratic tradition that draws profound inspiration from the American Enlightenment movement, emphasizing reason, individual rights, and popular sovereignty.

9. Economic Engine: Innovation, Prosperity, and Global Influence

The United States stands as a beacon of economic prowess, consistently identified as a developed country that ranks exceptionally high in economic competitiveness, innovation, and higher education. Its economic footprint is colossal, accounting for over a quarter of the nominal global GDP, and it has maintained its position as the world’s largest economy since approximately 1890. This enduring strength underscores a profound capacity for productivity and market dynamism that has few parallels on the international stage.

While its prosperity is undeniable, making it the wealthiest country with the highest disposable household income per capita among OECD members, it also grapples with significant challenges. The issue of wealth inequality is notably pronounced within its borders, highlighting an ongoing societal discussion about equitable distribution of its vast economic gains. This complex reality reflects both the immense opportunities within the American system and the persistent need for policies that promote broader economic inclusion.

Centuries of immigration have played an indispensable role in shaping the culture of the U.S., resulting in a vibrant tapestry that is both incredibly diverse and profoundly globally influential. This rich cultural exchange is reflected in its arts, entertainment, cuisine, and entrepreneurial spirit, which collectively have left an indelible mark on cultures worldwide. The blending of traditions and perspectives from every corner of the globe has not only enriched the American experience but has also served as a dynamic source of innovation and creativity.

Beyond its economic and cultural might, the United States commands an unparalleled military presence. It accounts for more than a third of global military spending, possessing one of the strongest militaries in the world and holding the status of a designated nuclear state. This formidable defense capability underpins its role as a major player in global political, cultural, economic, and military affairs. As a key member of numerous international organizations, the U.S. wields significant influence, actively shaping multilateral discussions and contributing to international stability and development, even amidst evolving global power dynamics.

The spirit of innovation, so central to America’s economic success, continues to drive its industries forward. While specific scientific and technological advancements of the 1990s were transformative, the nation’s commitment to research and development remains a constant. Its infrastructure, including advanced transportation networks and diversified energy sectors, supports this vast economy. From groundbreaking discoveries in spaceflight, pushing the boundaries of human exploration, to continuous improvements in energy efficiency and sustainable practices, the U.S. strives to maintain its leading edge, demonstrating an unwavering dedication to progress that keeps its economic engine humming and its global influence robust.

Read more about: Timeless Engineering, Iconic Style: Unpacking the Most Significant Cars of the 1940s

From the ancient footsteps of its first inhabitants to the vibrant complexity of its present-day society, America’s journey is a profound narrative of resilience, reinvention, and enduring impact. It’s a land where diverse cultures converge, where liberty has been fiercely fought for, and where the pursuit of progress continues to inspire. This intricate tapestry, woven from challenging histories, remarkable innovations, and an unyielding spirit, paints the picture of a nation that, through its dynamic evolution, constantly redefines what it means to be the United States of America.