You know that feeling when something you absolutely loved just… disappears? Like, one day it’s a staple, a comfort, a part of your daily joy, and the next, it’s just gone, leaving you wondering where it went and why it was taken from us. We’re talking about those cherished things that linger in our memories, sparking a powerful sense of nostalgia and a desperate need for answers about their untimely vanishing act. What happened? Who decided? Can we get it back?!

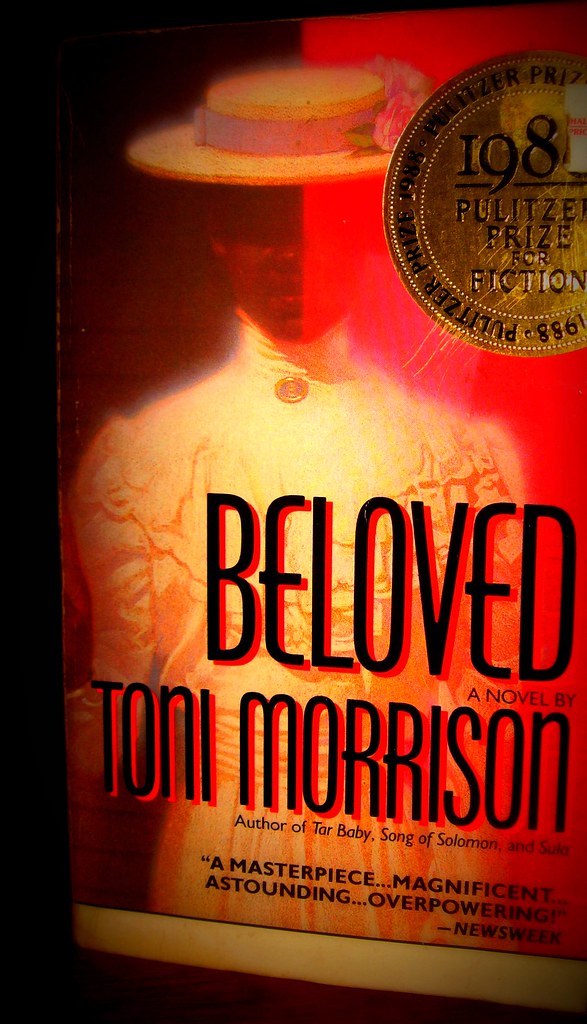

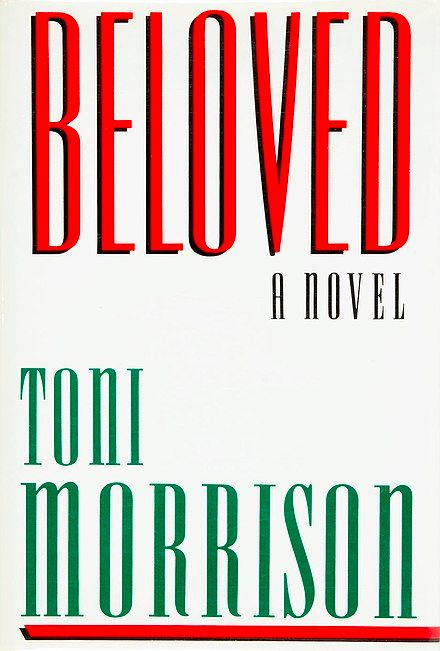

Well, buckle up, because today we’re diving deep into a “Beloved” that might not be a dessert, but it certainly leaves us with just as many profound, lingering questions – and perhaps even more emotional impact. We’re talking about Toni Morrison’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, “Beloved,” a story so powerful, so intricately woven with pain, resilience, and unyielding love, that its characters and themes continue to haunt our collective consciousness long after the final page. It’s a masterpiece that explores the brutal legacy of slavery and the enduring spirit of those who survived it.

So, forget those lost snacks for a moment, because we’ve got 13 truly essential elements from this literary giant that deserve our full attention. We’re breaking down the complex individuals and the massive ideas that drive this narrative, starting with some of the most unforgettable characters who faced unimaginable horrors, fought for their humanity, and left us all pondering the deepest questions of existence. Get ready to explore the hearts and minds that make “Beloved” an eternal conversation starter.

1. Sethe

Sethe is undeniably the fierce heart of “Beloved,” the protagonist whose journey from the Sweet Home plantation defines the novel’s powerful emotional core. She’s depicted as a formerly enslaved woman, living at 124 Bluestone Road in Cincinnati, Ohio, a place that’s as much a character as anyone else, haunted by the ghost of her eldest daughter. Sethe’s character is built on resilience, a will to survive that is both awe-inspiring and heartbreakingly tragic. Her escape from slavery, bearing the literal and metaphorical scars of whips on her back, described as “a tree on her back,” speaks volumes about the physical and psychological torment she endured.

Her life at 124 Bluestone Road with her daughter Denver is profoundly shaped by the trauma she experienced. Her two sons, Howard and Buglar, had already fled by the age of 13, which Sethe believes was due to the haunting spirit. This early isolation sets the stage for the intense, often suffocating, mother-daughter bonds that become a central theme. Sethe’s defining trait is her extreme, almost dangerous, maternal passion. She would do anything to protect her children from the abuses she suffered, a conviction so strong that it leads to an act of profound desperation and love, believing she was “trying to put my babies where they would be safe.”

The narrative paints Sethe as someone deeply influenced by the repression of her trauma. She tries to keep her past at bay, but it constantly resurfaces, embodied by the return of Beloved. This struggle to reconcile her past self with her present identity is a constant battle. The painful memories of Sweet Home, especially the theft of her milk, leave her unable to form typical symbolic bonds with her children. Her love, as Paul D remarks, is “too thick,” but Sethe vehemently counters that “thin love is no love,” highlighting her unwavering belief in the righteousness of her actions, even when facing societal scorn.

Despite the horrific choices she made, Sethe is presented as a type of hero, not conventional, but one who acts in the face of immense opposition, driven by what she believes is right for her loved ones. She justifies her actions by saying, “It ain’t my job to know what’s worse. It’s my job to know what is and to keep them away from what I know is terrible. I did that” (194). Her eventual journey towards self-acceptance, encouraged by Paul D, marks her slow, arduous path to individuation, a poignant conclusion to a life defined by unimaginable suffering and fierce maternal protection.

Read more about: The One Question That Made Tom Cruise Storm Off Set: Unpacking the Tense Interview Moment That Left Fans Divided

2. Beloved

Now, let’s talk about the character who literally embodies the title and who sparks some of the novel’s most intense debates: Beloved herself. She appears mysteriously from a body of water, discovered soaking wet on the doorstep of 124 Bluestone Road, and is taken in by Sethe, Paul D, and Denver. Right away, her presence is a game-changer, as the haunting that had plagued the house for years suddenly ends. This, combined with her childlike behavior, leads many to believe she is the ghost of Sethe’s murdered infant daughter, returned to them in physical form.

The context explicitly states that “Morrison stated that the character Beloved is the daughter who Sethe killed.” This direct confirmation from the author adds a layer of tragic certainty to her spectral arrival. Her name itself is a profound symbol, derived from the single word Sethe could afford to have engraved on her baby’s tombstone because she couldn’t afford “Dearly” or anything more elaborate. This makes Beloved not just a person, but a living memorial, a walking embodiment of grief, memory, and the unspoken horrors of the past.

Beloved’s role in the narrative is nothing short of catalytic. She acts as a powerful force, dredging up the repressed traumas and painful memories of Sethe, Paul D, and Denver, forcing them to confront their pasts. However, her presence is not purely redemptive. As the story progresses, she becomes increasingly demanding and parasitic, creating madness within the house and slowly draining Sethe of her vitality, resources, and even her sense of self. Sethe, consumed by guilt and overjoyed at her daughter’s apparent return, devotes all her time and money to Beloved, trying desperately to explain her actions.

Her consumption of Sethe, her physical growth to “a pregnant woman,” and the eventual merging of Sethe and Beloved’s voices until they are “indistinguishable,” highlight the destructive nature of unaddressed trauma and guilt. Beloved represents the weight of the past, a constant reminder of the unspeakable. Her disappearance at the novel’s climax, through the collective action of the community and Denver’s burgeoning independence, signifies a necessary exorcism—not just of a ghost, but of the paralyzing grip of memory, allowing the survivors to finally begin the painful process of healing and moving forward.

Read more about: Remembering the Legends: A Tribute to the Departed Stars Who Shaped ‘The Terminator’ Franchise

3. Paul D

Paul D is another survivor of Sweet Home, and his journey offers a crucial masculine perspective on the psychological aftermath of slavery. He retains his name from enslavement, a stark reminder of the dehumanizing practice where most enslaved men at Sweet Home were simply named “Paul.” Before his arrival at 124, he had been moving around continuously, carrying with him a heavy burden of painful memories from enslavement and the horrors of being forced into a chain gang. He represents the wandering, dispossessed male slave, trying to find a place of belonging and peace after emancipation.

A defining image for Paul D is his “tobacco tin” heart, a metaphor for how he has compartmentalized and repressed his agonizing memories to survive. He keeps his pain locked away, shielded from himself and others. However, Beloved’s arrival acts as a key, opening that tin and forcing him to confront his stored traumas, including the ual violence he and other men suffered in the chain gang. This vulnerability, brought on by Beloved, allows for a deeper connection with Sethe but also reveals the depth of his own wounded psyche.

Upon reuniting with Sethe, an old acquaintance from Sweet Home, they begin a romantic relationship, offering a fragile hope for a new beginning. He acts as a father figure to Denver and is the first to be suspicious of Beloved’s true nature, recognizing the unsettling energy she brings. Despite their shared past and burgeoning intimacy, Paul D struggles to fully understand Sethe, particularly her fierce motherhood and the unique traumas she carries. His initial inability to comprehend her actions—telling her her love is “too thick” and that “you’ve got two feet, not four”—underscores the distinct ways men and women processed and expressed their survival.

Ultimately, Paul D’s journey is one of rediscovery and healing. The context points to his initial diminished “maleness” due to slavery and its aftermath, and how Sethe’s gentle acceptance, her “tenderness about his neck jewelry,” allows him to reclaim his manhood. He finds solace in Sethe, recognizing her as the only woman who “could have left him his manhood like that.” His return to Sethe at the novel’s end, encouraging her to see herself as her own “best thing” after Beloved’s disappearance, signifies a powerful step towards mutual healing and a future built on genuine, restorative love, free from the haunting past.

Read more about: Remembering the Legends: A Tribute to the Departed Stars Who Shaped ‘The Terminator’ Franchise

4. **Denver**Denver, Sethe’s only surviving child who still lives at 124, undergoes one of the most significant transformations in “Beloved.” Initially portrayed as shy, friendless, and housebound, she exists in a state of profound isolation, having been cut off from the Black community after the devastating act of infanticide committed by her mother. Her early companionship is the ghost that haunts their home, a chilling testament to her loneliness. Her bond with her mother is intense, a result of their shared solitude and Denver’s fear of the outside world.

Beloved’s arrival is a pivotal moment for Denver. Initially, she’s “eager to care for the sickly Beloved,” believing her to be her older sister returned. This new connection provides her with a sense of purpose and belonging, a companion to fill the void left by her brothers’ departure and the community’s ostracization. However, as Beloved’s influence becomes more sinister and consuming, Denver’s perspective shifts. She witnesses Beloved’s “demonic activity” and observes her mother becoming more childlike, while Beloved takes on a maternal, demanding role. This reversal of roles and the growing terror push Denver towards her own awakening.

The novel beautifully charts Denver’s journey from a dependent, childish figure to a fiercely protective and independent woman. She realizes the destructive path Sethe and Beloved are on, understanding that “neither Beloved nor Sethe seemed to care what the next day might bring.” This realization forces her to confront her fears and break the cycle of isolation that has defined her life at 124. The context highlights this heroic step: “Denver knew it was on her. She would have to leave the yard; step off the edge of the world, leave the two behind and go ask somebody for help” (286).

Her decision to step “off the edge of the world” is a powerful metaphor for her courage, symbolizing her breaking free from the suffocating grip of the past and the confines of her home. By reaching out to the Black community, from whom they had been isolated due to envy of Baby Suggs’ privilege and horror at Sethe’s act, Denver initiates the community’s intervention. This act of seeking help is her “threshold of heroism,” rescuing her mother from Beloved’s parasitic hold and paving the way for her own individuation. At the end, Denver becomes “a working member of the community,” embodying hope and the possibility of a future free from the past’s burdens.

Read more about: Your Ultimate Guide: 14 Lifehacker Strategies to Get the Absolute Best Price on a New Car

5. **Baby Suggs**Baby Suggs, Sethe’s mother-in-law and Halle’s mother, is a truly iconic figure in “Beloved,” representing both profound spiritual wisdom and the crushing weight of systemic oppression. Her story begins with her son, Halle, working tirelessly to buy her freedom, a testament to the enduring power of family bonds even under slavery. After gaining her freedom, she travels to Cincinnati and establishes herself as a revered leader in the Black community, renowned for her powerful sermons in the “Clearing.”

Her preaching is incredibly significant, a beacon of hope and self-affirmation for the newly freed. She urges Black people to love themselves, their bodies, and their spirits, because, as she knew all too well, “other people will not.” This message of radical self-love in a society that denied their humanity was revolutionary and deeply impactful. She creates a space where the community can find healing, express their pain, and embrace their worth.

However, Baby Suggs’ respected position takes a turn. Her generous act of turning “some food into a feast” for the community earns their envy, ironically isolating her even before Sethe’s act of infanticide completely alienates the family. This highlights the fragility of community and the destructive power of envy, even among those who share similar struggles. After Sethe kills her daughter and the community withdraws, Baby Suggs, devastated by the horrors she has witnessed and the renewed isolation, “retires to her bed.”

In her final years, she spends her time thinking about “pretty colors,” a poignant retreat from the ugliness of the world and a reflection of her profound disillusionment. She dies at 70, eight years before the novel’s main events begin, but her spiritual presence and her lessons on self-love continue to resonate throughout the story. Her character is a powerful reminder of the deep scars slavery left, not just on individuals, but on community cohesion and the ability to maintain hope in the face of relentless despair.

Read more about: Unearthing Trauma: The Enduring Narrative of ‘Beloved’ for a Dark and Gritty Live-Action Reboot

6. **Halle**Halle, the son of Baby Suggs, husband of Sethe, and father of her children, is a character whose presence is largely felt through absence and memory in “Beloved.” We learn of him primarily through flashbacks, as he and Sethe were married at the notorious Sweet Home plantation. His ultimate fate, and the circumstances of his separation from Sethe during her escape, remain shrouded in a tragic mystery that underscores the brutal fragmentation of enslaved families.

The context provides glimpses into Halle’s character through the eyes of others. He is described as hardworking and good, qualities that Paul D later recognizes in Denver, suggesting a positive lineage. Baby Suggs, however, “fears [these qualities] make him a target,” hinting at the vulnerability that goodness could create in the harsh world of slavery. His dedication to his mother, working to buy her freedom, speaks volumes about his character and his deep familial loyalty, a stark contrast to the system that sought to deny such bonds.

The last anyone sees of Halle is Paul D observing him “churning butter at Sweet Home.” This seemingly mundane image is immediately followed by the devastating revelation that “He is presumed to have gone mad after seeing residents of Sweet Home violating Sethe.” This moment of profound trauma, witnessing the unspeakable abuse of his wife, shatters him, driving him into a state of madness and effectively removing him from the narrative’s present. His mental collapse is a stark illustration of the psychological torture inflicted by slavery, where even the strongest minds could break under the weight of such inhumanity.

Halle’s “disappearance” isn’t a physical vanishing act like Beloved’s, but a descent into an unknowable mental abyss, leaving Sethe to bear the burdens of their past alone. He becomes a symbol of the broken promises of family under slavery, and the deep, irreparable wounds inflicted upon men who were powerless to protect their loved ones. His madness is a quiet, haunting tragedy, a testament to the profound and lasting damage of Sweet Home, a wound that continues to ripple through Sethe’s life and choices long after his presumed demise.

Alright, so we’ve journeyed through the minds and hearts of six incredible individuals who make ‘Beloved’ an unforgettable experience. But trust us, the story’s depth doesn’t stop there! Just like that dessert you *know* you loved but can’t quite recall the recipe for, there are more pieces to this profound puzzle, more characters and overarching ideas that cement ‘Beloved’ as an absolute literary titan.

We’re not just talking about the major players, either. Sometimes, even the characters who show up for a brief, impactful moment, or the insidious forces they fight against, leave an impression that lingers forever. And let’s be real, a story this rich is built not just on its people, but on the massive, universal themes that tie everything together, forcing us to confront uncomfortable truths and celebrate the enduring human spirit. Get ready to dive deeper into the forces that shape this unforgettable narrative, from the chilling antagonist to the profound human experiences that Morrison so masterfully unpacks.

Read more about: Totally Tubular! 12 Earth-Shattering Events That Made The ’90s The Unforgettable Decade We Still Obsess Over!

7. **Schoolteacher**If there’s one character who makes your skin crawl and represents the absolute worst of humanity, it’s Schoolteacher. He’s not just a person; he’s the embodiment of the systematic cruelty and dehumanization that defined the Sweet Home plantation. The context plainly states that he is “the primary discipliner, violent, abusive, and cruel to the people he enslaved at Sweet Home, whom he views as animals.” Just let that sink in for a moment – viewing human beings as mere property, as less than human. It’s truly chilling.

His presence hangs like a dark cloud over Sethe’s entire existence, even long after she escapes. We learn that it’s his pursuit of Sethe following her escape that triggers her most desperate and heartbreaking act. Imagine the terror, the sheer panic, that would drive a mother to such extremes. The novel lays it bare: “he comes for Sethe following her escape, but she kills her daughter and is arrested, instead.” This horrific event is a direct consequence of Schoolteacher’s relentless brutality and the system he upholds.

Schoolteacher isn’t just a villain; he’s a stark symbol of the pervasive, institutionalized violence of slavery. His actions and his philosophy underscore the sheer injustice and trauma that enslaved people faced daily. His character is a constant reminder of what Sethe and others were trying to escape, and why their scars, both visible and invisible, ran so deep. He’s the antithesis of everything humane, a necessary, albeit terrifying, figure to fully grasp the stakes of freedom and the depths of the pain explored in the novel.

Read more about: Claudia Cardinale, Italian Cinema’s Enduring Star and ‘Dream Girl,’ Dies at 87

8. **Amy Denver**Amidst the overwhelming darkness and despair, sometimes a flicker of unexpected kindness can shine through, and that’s precisely what we find with Amy Denver. She’s a young white girl, herself on a journey to Boston, when she stumbles upon Sethe, who is desperately trying to reach safety. Sethe is not just fleeing but is also “extremely pregnant at the time, and her feet are bleeding badly from the travel.” The contrast between Sethe’s harrowing escape and Amy’s relatively less perilous journey is stark.

Amy’s actions are nothing short of a miracle in a world steeped in cruelty. The context highlights how “Amy helps nurture her and deliver Sethe’s daughter on a small boat, and Sethe names the child Denver after her.” This isn’t just a helping hand; it’s an act of profound compassion, a moment of shared humanity between two individuals from vastly different worlds, yet both vulnerable in their own ways. It’s a testament to the fact that even in the most brutal of times, decency can emerge.

Her role, though fleeting, is incredibly significant. Amy Denver represents a rare instance of interracial empathy and support, a stark counterpoint to the systemic racism and violence that defines so much of the narrative. Her unexpected assistance not only saves Sethe’s life and her baby’s but also offers a brief, powerful glimpse into the possibility of connection and shared struggle. It reminds us that humanity isn’t always lost, even when it feels like it’s teetering on the brink.

Read more about: Unearthing Trauma: The Enduring Narrative of ‘Beloved’ for a Dark and Gritty Live-Action Reboot

9. **Mother-Daughter Relationships**Okay, prepare yourself, because the mother-daughter relationships in ‘Beloved’ are a whole tangled mess of love, trauma, and devastating consequences. This theme isn’t just a subplot; it’s the very heartbeat of the novel, especially when it comes to Sethe. Her maternal bonds are so intense, so all-consuming, that they actually “inhibit her own individuation and prevent the development of her self.” Imagine loving so fiercely that it threatens to erase who you are!

The tragic irony here is that Sethe’s “dangerous maternal passion” leads to the very act she believes will save her children: killing one daughter, an act described as destroying her “own ‘best self.'” And the ripple effects don’t stop there. Her surviving daughter, Denver, becomes “estranged from the Black community,” a direct result of her mother’s actions and the community’s judgment. Sethe, in her fervent desire to protect, often misses what Denver truly needs, as she “fails to recognize her daughter Denver’s need for interaction with the Black community to enter into womanhood.” It’s a heartbreaking cycle.

Slavery, as the novel powerfully illustrates, ripped these natural bonds to shreds. “Under slavery, mothers lost their children, with devastating consequences for both.” It’s why Sethe clings so desperately, unlike Baby Suggs, who, after losing so many, learns to detach to survive. Sethe’s love, while undeniably deep, becomes “too thick,” a protective shield that ultimately suffocates.

We can’t forget the profound trauma of having her milk stolen, an experience that leaves Sethe “unable to form the symbolic bond between herself and her daughter by feeding her.” This literal theft of nourishment becomes a metaphor for the deeper emotional and psychological ruptures slavery inflicted on the sacred bond between mother and child. It’s a pain that permeates her every interaction, fueling her desperate acts of love.

Ultimately, the novel shows us a path, however arduous, towards healing. Denver, through her own courage, eventually breaks free and establishes her own self. And Sethe? “Sethe only becomes individuated after Beloved’s exorcism. Then, she is free to fully accept the first relationship that is completely ‘for her,’ her relationship with Paul D.” It’s a journey from self-destruction driven by maternal guilt to the possibility of a love that is truly restorative.

Read more about: 15 Tear-Jerking Movies: Get Your Tissues Ready for an Emotional Rollercoaster

10. **Psychological Effects of Slavery**You know how sometimes you just want to bury a bad memory so deep it ceases to exist? Well, for the formerly enslaved characters in ‘Beloved,’ that impulse was a matter of survival. The psychological toll of slavery was immense, and most survivors “tried to repress these memories in an attempt to forget the past.” But here’s the kicker: this repression, this desperate attempt to dissociate, actually led to “a fragmentation of the self and a loss of true identity.” It’s like trying to cut off a part of yourself, only to find the wound festers deeper.

Sethe, Paul D, and Denver all grapple with this fractured sense of self, living with pieces of their past locked away. Their healing, their ability to become whole again, is entirely dependent on their willingness and capacity to “reconcile their pasts and memories of earlier identities.” It’s a painful but necessary journey of retrieving those lost parts of themselves, a kind of internal archaeology.

This is where Beloved comes in, acting as a living, breathing (or haunting, depending on your read!) catalyst. She “serves to remind these characters of their repressed memories, eventually leading to the reintegration of their selves.” It’s unsettling, yes, but her presence forces them to confront the very horrors they’ve tried so hard to forget, pushing them towards a reckoning that is both agonizing and essential for their healing.

The novel eloquently describes this profound damage: “The identity, consisting of painful memories and unspeakable past, denied and kept at bay, becomes a ‘self that is no self’.” Imagine existing in such a state, where your own story is fractured, unacknowledged, and unspoken. To truly heal and become human again, one must reconstruct this identity, “constitute it in a language, reorganize the painful events, and retell the painful memories.” It’s about owning your narrative, no matter how brutal it is.

But there’s a huge catch. The context highlights that “The barrier that keeps them from remaking of the self is the desire for an ‘uncomplicated past’ and the fear that remembering will lead them to ‘a place they couldn’t get back from’.” It’s the ultimate Catch-22: you need to remember to heal, but remembering is terrifying because the past is so horrific. This profound internal conflict is a central, agonizing aspect of ‘Beloved’s’ psychological landscape.

Read more about: 10 Films That Sparked Global Outrage and Divided Audiences Forever

11. **Definition of Manhood**Beyond the deeply emotional arcs of motherhood and trauma, ‘Beloved’ also throws a spotlight on what it means to be a man, especially when a brutal system actively works to strip you of your very essence. The narrative powerfully shows how slavery “distorts a man from himself,” challenging conventional notions of masculinity and forcing characters like Paul D to redefine it on their own agonizing terms.

Paul D’s internal struggle is a perfect illustration. His “tobacco tin” heart, a metaphor for how he compartmentalizes and represses his painful memories, is his way of surviving. But the norms and values of white culture, ingrained through slavery, constantly challenge his “depiction of manhood.” How can you be a man, a protector, when you are systematically denied agency and subjected to unspeakable horrors?

The novel doesn’t shy away from the horrific ual violence inflicted upon Paul D and other men in the chain gang, explaining how his “reduced manhood emerges in relation to a discourse of animality.” It’s a stark portrayal of how slavery dehumanized men, reducing them to mere beasts of burden, stripping them of their dignity and their very identity. This profound assault on their maleness leaves deep, often unseen, scars.

This struggle for identity extends beyond emancipation into the Reconstruction era, where “Jim Crow laws were put in place to limit the movement and involvement of African Americans in the White-dominant society.” Black men like Paul D found themselves in a society that still denied them their goals and dreams, constrained to a “lower-status” because of the color of their skin. It’s a powerful statement on how systemic oppression continued to limit their ability to define their own worth.

Yet, there’s hope in Paul D’s journey. His eventual return to Sethe, and her unique “tenderness about his neck jewelry,” allows him to reclaim what slavery tried to steal. Sethe’s non-judgmental acceptance of his scars is pivotal, as “Only this woman Sethe could have left him his manhood like that.” It’s a testament to the healing power of genuine love and acceptance, allowing him to finally see himself as whole, not just as a victim.

Read more about: Decoding Old English: Essential Facts About the Anglo-Saxon Language You Should Know

12. **Family Relationships**Let’s talk about family, because in the era of slavery, the very concept of a family unit was under constant, brutal assault. ‘Beloved’ vividly portrays how “Family relationships are an instrumental element… which help visualize the stress and the dismantlement of African-American families in this era.” Enslaved people had no legal rights to themselves, their spouses, or, most tragically, their children. This fundamental denial of familial bonds created unimaginable pain and profound societal scars.

Sethe’s decision to kill Beloved, as horrifying as it is, is presented through the lens of this brutal reality. It was “deemed a peaceful act because Sethe believed that killing her daughter was saving her.” She saw it as the only way to spare her child from the unfathomable horrors she herself had endured. But this desperate act, while born of fierce maternal love, ultimately “divided and fragmented” her family, mirroring the brokenness of the wider society.

Even after the Emancipation Proclamation, the wounds lingered. “Formerly enslaved families were broken and bruised because of the hardships they faced while they were enslaved.” Freedom didn’t magically erase the trauma of forced separations, the sale of children, or the impossibility of stable family life. The journey to healing and rebuilding was, and remains, a long and arduous one, fraught with the ghosts of the past.

Beloved herself, in her mysterious return, becomes a living embodiment of these fractured family ties and the deep mental strife Sethe faces. Her appearance at 124 Bluestone Road, following Sethe’s first social outing since the infanticide, is no coincidence. She is the haunting past made flesh, forcing Sethe to confront the deepest, most agonizing consequences of her actions and the indelible mark slavery left on her ability to nurture and protect her loved ones.

Read more about: But Why Did They Stop? 12 Life-Altering Experiences That Vanished on ‘Old’s’ Cursed Beach

13. **Pain**Oh, the pain. It’s not just a theme in ‘Beloved’; it’s a pervasive, almost tangible force that saturates every page, every character, every memory. The context asserts that “The pain throughout this novel is universal because everyone involved in slavery was heavily scarred, whether that be physically, mentally, sociologically, or psychologically.” It’s a multi-layered agony that permeates every facet of existence for those touched by its shadow.

What’s particularly poignant, and unsettling, is the way some characters try to “romanticize” or “beautify” their pain. Sethe, for instance, clings to a white girl’s description of her whipped back, calling the horrific scars “a Choke-cherry tree. Trunk, branches, and even leaves.” She repeats this to everyone, trying to find some semblance of beauty in an experience that was pure torture. It’s a desperate attempt to reshape trauma into something bearable, perhaps even poetic.

But not everyone buys into this attempt to sugarcoat suffering. Paul D and Baby Suggs, having witnessed and experienced the raw brutality of slavery themselves, “both look away in disgust and deny this description of Sethe’s scars.” They understand that there’s no beauty in such pain, only the grotesque reality of what was done. Their reactions highlight the profound difference in how individuals process and internalize their suffering.

Sethe does something similar with Beloved’s return. The context reveals that “Sethe does the same with Beloved. The memory of her ghost-like daughter plays a role of memory, grief, and spite that separates Sethe and her late daughter.” Instead of confronting the agonizing reality of her child’s murder, Sethe embraces Beloved, seeing her “all grown and alive, instead of the pain of when Sethe murdered her.” It’s a powerful defense mechanism, an attempt to replace a horrific memory with a comforting (yet ultimately destructive) fantasy.

The novel’s conclusion, though still laced with sorrow, offers a glimmer of hope for moving beyond this paralyzing pain. When Beloved is finally gone, Paul D encourages Sethe to love herself, to see herself as her “own ‘best thing’.” It’s a vital step towards self-acceptance and healing, suggesting that true recovery lies not in romanticizing or repressing pain, but in acknowledging it and choosing to value one’s own existence beyond the scars of the past.

Wow, what a journey! Diving into the world of Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’ is never just reading a book; it’s an immersive experience that pulls you deep into the human spirit’s capacity for both immense suffering and incredible resilience. From the unforgettable characters like Sethe and Paul D, grappling with unimaginable pasts, to the insidious forces like Schoolteacher, and the unexpected kindness of Amy Denver, every element is woven together to create a tapestry of profound emotional truth.

Read more about: Totally Tubular! 12 Earth-Shattering Events That Made The ’90s The Unforgettable Decade We Still Obsess Over!

And let’s be honest, the themes—oh, the themes! Mother-daughter relationships twisted by trauma, the crushing psychological burden of slavery, the ongoing struggle to define manhood in the face of dehumanization, the fractured mosaic of family ties, and the ubiquitous, searing presence of pain—these aren’t just literary concepts. They are echoes of history, ringing truths that resonate powerfully even today. ‘Beloved’ isn’t just a story about a specific time; it’s a timeless testament to the enduring human spirit, a powerful call to remember, to confront, and ultimately, to heal. It reminds us that while some things may vanish, the most important stories, like the love and lessons embedded in this novel, live on forever, shaping our understanding of the world and ourselves.