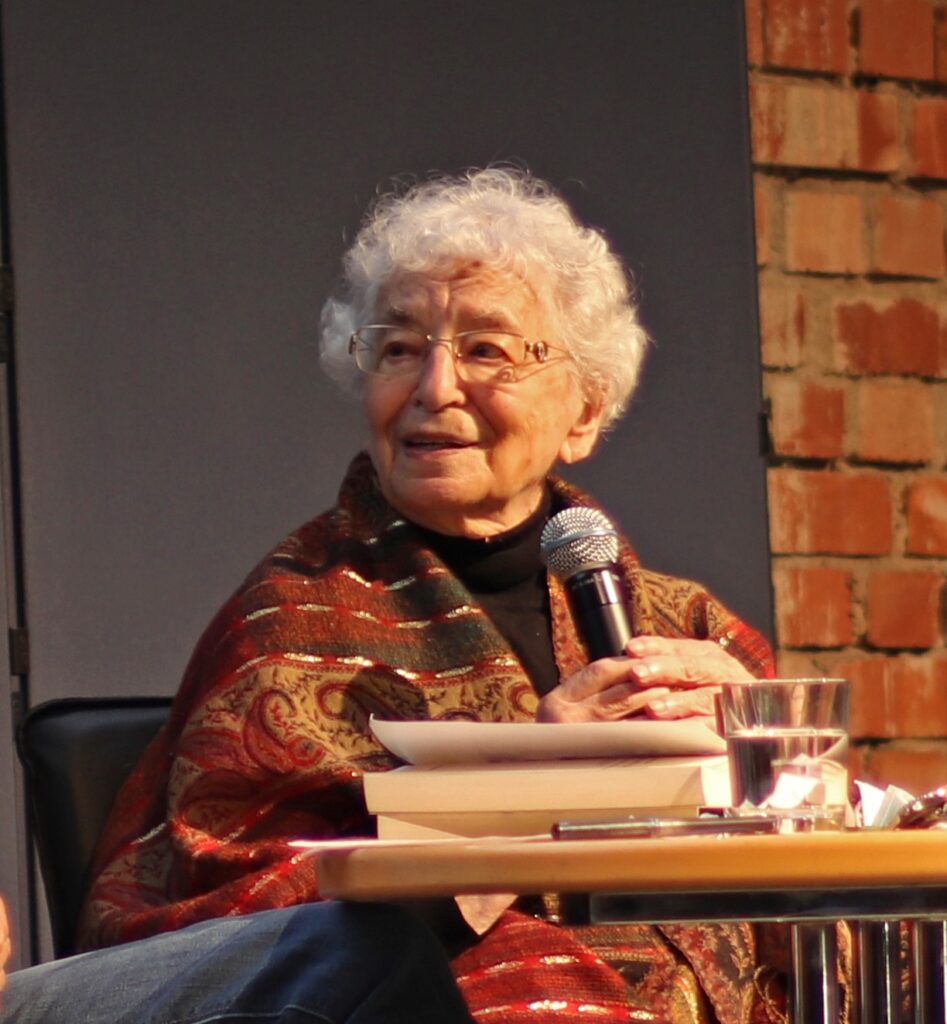

Ruth Weiss, a formidable South African journalist whose life and prodigious body of work were profoundly shaped by the twin traumas of Nazi persecution and the systemic brutality of apartheid, died on September 5 at a hospital in Aalborg, Denmark. She was 101. Her passing marks the end of an era for a woman whose experiences of discrimination from a young age transformed her into an unyielding opponent of injustice, a witness who repeatedly found herself at the confluence of history’s most harrowing chapters.

Her death was announced by the nonprofit organization Ruth Weiss Gesellschaft, founded by her friends in Germany to promote her extensive work. Ms. Weiss’s journey from an object of exclusion and persecution in her childhood to an articulate, incisive chronicler of oppression in her adulthood is a testament to her profound moral conviction and intellectual courage. Her life offers an extraordinary narrative of resilience and unwavering commitment to journalistic integrity, often at great personal cost.

Ms. Weiss’s impactful career spanned decades and continents, producing hundreds of articles and numerous books that consistently brought to light the realities of discriminatory regimes. Her ability to draw parallels between disparate forms of oppression, most notably between the suffering of Jews under the swastika and Blacks under apartheid, provided a unique and powerful lens through which to understand human rights struggles globally. Her contributions to journalism and her fearless advocacy cemented her legacy as a vital voice for justice.

1. **Fleeing Nazi Persecution and a Childhood Upended**Ruth Löwenthal was born on July 26, 1924, in Fürth, Germany, the younger of two daughters to Richard Löwenthal, who worked in the toy industry, and Selma (Cohen) Löwenthal. Her early childhood, which she described as idyllic, was abruptly shattered in 1933 with the rise of the Nazis to power. This seismic shift marked the beginning of a life defined by displacement and the stark reality of systemic hatred.

“I no longer had any friends,” she wrote in her memoir, reflecting on the immediate and devastating impact of the Nazi regime on her daily life. She recounted how classmates would distance themselves from her, creating an isolating environment: “Everyone sat as far away from me as possible. During the break, no one came near me.” This early experience of ostracism and persecution imprinted upon her a lifelong understanding of the mechanisms of discrimination.

When her father lost his job, the family was compelled to seek refuge. Relatives in South Africa extended an invitation for him to immigrate, a lifeline that the Löwenthal family seized. Three years after the Nazis took power, in 1936, the family joined him in Johannesburg, leaving behind a homeland that had turned hostile. This forced migration was one of the last refugee boats allowed into South Africa, underscoring the urgency and desperation of their flight.

Her experience as a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany provided a foundational understanding of the nature of persecution. This firsthand encounter with state-sponsored discrimination would deeply inform her perspectives and future work, laying the groundwork for her later ability to empathize with and articulate the struggles of others facing similar injustices. It transformed her into a perpetual witness, sensitizing her to the subtle and overt signs of systemic oppression.

2. **Immigration to South Africa and the Ironies of Refuge**The family’s arrival in Johannesburg in 1936 presented a complex reality. While South Africa offered a haven from the immediate threat of Nazi extermination, it simultaneously exposed Ruth Weiss to another entrenched system of racial hierarchy: apartheid. This paradox of escaping one form of discrimination only to encounter another would become a central theme of her life’s work and reflections.

Ms. Weiss candidly addressed this irony, stating, “We had the right skin color, even if we had the wrong religion.” This observation, made to an interviewer for the German public broadcaster Deutsche Welle, succinctly captured the superficiality of racial classification and the conditional nature of their acceptance. Their physical appearance granted them certain privileges, yet their Jewish identity, a source of persecution elsewhere, remained a distinct, though less immediately life-threatening, marker.

This new environment, while safer, did not offer true liberation from the shadow of prejudice. The very system that allowed them entry as white Europeans was built upon the subjugation of the Black African majority. The contrast between her family’s experience as refugees and the ongoing oppression of Black South Africans sharpened her awareness of injustice, shaping her resolve to resist all forms of dehumanization.

Her presence in South Africa as a refugee from Nazi Germany lent her a unique perspective on the unfolding apartheid regime. It instilled in her a profound empathy for those systematically marginalized and dispossessed, and a fierce determination to speak truth to power. This period marked a crucial pivot point, transforming her from a victim of historical events into an active, critical observer and, eventually, a powerful voice against institutionalized racism.

3. **Witnessing Apartheid: Early Encounters with Systemic Injustice**Upon arriving in South Africa, Ruth Weiss was immediately confronted with the burgeoning system of apartheid, an institutionalized form of racial segregation and discrimination. Her discursive memoir, “A Path Through Hard Grass: A Journalist’s Memories of Exile and Apartheid,” published in 2014, is replete with her “repugnance at the brutal treatment of Black people” that she witnessed as a young woman in her adopted homeland. This visceral reaction to injustice became a driving force throughout her career.

Her experiences as a refugee from Nazi Germany provided her with an uncomfortably clear lens through which to view apartheid. In a seminal lecture in Nuremberg, Germany, in 1979, she posed a stark, challenging question that encapsulated her perspective: “Blacks under apartheid — Jews under the swastika. Was it all that different?” She concluded, unequivocally, that it was not, highlighting the shared mechanisms of exclusion, dehumanization, and state-sanctioned violence that underpinned both regimes.

Even before she formally embarked on her journalistic career, Ms. Weiss’s hatred of apartheid was resolute and openly expressed. She famously confronted her employer at an insurance company, a nationalist Afrikaner named Chris Bischoff, with her views. “I don’t like your system,” she recalled telling him. “I think it’s unjust and must be abolished.” This bold declaration, made in a climate of intense suppression, underscores her innate moral courage and refusal to remain silent.

Her early observations and direct confrontations cemented her resolve to fight against racial injustice. The parallelism she drew between her own past trauma and the ongoing suffering of Black South Africans underscored a universal truth about the nature of prejudice, elevating her personal experience into a powerful analytical framework for understanding human rights abuses. This formative period cultivated her identity as an uncompromising advocate for equality.

4. **An Unexpected Start in Journalism: Ghostwriting for ailing Husband**Ruth Weiss’s entry into the demanding world of journalism was, by her own account, serendipitous and born out of necessity rather than a direct ambition. During the 1950s in Johannesburg, she was married to Hans Weiss, a fellow refugee journalist who served as a correspondent for German newspapers. However, Hans frequently suffered from depression and other illnesses, which often incapacitated him and prevented him from fulfilling his professional duties.

In a remarkable display of support and a burgeoning talent, Ms. Weiss began writing some of his articles for him, initially penning pieces focused on economics. Her prior professional experience working for a large South African insurance company had equipped her with a solid understanding of financial matters, making her uniquely suited for this task. It was through these ghostwritten assignments, published under her husband’s name, that she inadvertently found her calling and honed her journalistic skills.

This unconventional apprenticeship not only kept her husband’s career afloat but also served as a clandestine training ground for her own. She gradually took over more of his journalistic work, a pattern that, as she recounted in her memoir, “became the pattern of our lives.” This period of anonymous contributions allowed her to develop her voice, research abilities, and reporting acumen without the immediate pressures of public recognition.

Her willingness to write on behalf of someone else, a quality her friend Nadine Gordimer described as “natural modesty,” paradoxically launched her into a distinguished career. It underscored a fundamental aspect of her character: a commitment to the task and the truth, irrespective of personal glory. This humble beginning laid the groundwork for her later emergence as a prominent and respected voice in African and international media.

5. **Blossoming as an Independent Journalist Under Her Own Name**As her marriage to Hans Weiss began to encounter difficulties and eventually foundered in the early 1960s, Ruth Weiss’s journalistic career underwent a profound transformation. Released from the need to ghostwrite, she blossomed as an independent journalist, finally publishing under her own name and establishing her distinct identity within the media landscape. This period marked her emergence as a powerful and recognized voice.

Her newfound independence saw her assume significant editorial roles. She became the business editor of News Check, a fortnightly South African magazine, where her insights into the economic realities of the region were highly valued. Following this, she took on the role of a correspondent for the country’s leading business weekly, Financial Mail, further solidifying her reputation as an incisive economic journalist.

These positions allowed her to accept overseas assignments, extending her reporting reach throughout Africa and Europe. Ms. Weiss described this era as “an exciting and busy time for the media,” reflecting the dynamism and critical importance of journalism during a period of intense political and social upheaval. Her work provided crucial context and analysis for a readership grappling with rapid changes.

By this point, Ms. Weiss was not merely reporting on events; she was actively shaping public understanding of complex issues. Her transition from an anonymous contributor to a celebrated journalist operating under her own name was a testament to her inherent talent, intellectual rigor, and unwavering dedication to her craft. She had found her authentic voice and a platform from which to articulate her deep-seated opposition to injustice.

Read more about: The Tragic End of a Rising Star: Rebecca Schaeffer’s Legacy in the Fight Against Stalking

6. **Covering Pivotal Moments in South Africa’s Struggle for Liberation**During her tenure with News Check and the Financial Mail, Ruth Weiss found herself at the journalistic forefront of South Africa’s most pivotal and tumultuous years. Her reporting captured the unfolding drama of a nation in profound transition, providing crucial documentation of historical events that would redefine the country. She covered the emergence of key anti-apartheid movements and the government’s escalating response.

“We covered the emergence of MK,” she wrote, referring to Umkhonto we Sizwe, the military wing of the African National Congress, which was then the oldest liberation movement in Africa. Her articles also detailed “the arrests and detentions” of anti-apartheid activists, illuminating the severe repression faced by those challenging the regime. These were not abstract reports but chronicles of real people facing dire consequences for their beliefs.

Ms. Weiss also meticulously reported on a significant constitutional shift: “the government’s decision to leave the Commonwealth and turn South Africa into a republic on 31 May 1961.” This event signaled a hardening of the apartheid state’s resolve and its increasing isolation on the international stage, a development she keenly observed and analyzed for her readers.

Her work during this period was not merely factual reporting; it was a powerful act of witnessing, lending a voice to those silenced and exposing the machinery of an oppressive state. Through her precise and authoritative prose, she provided an invaluable historical record of South Africa’s struggle, embodying the principles of independent journalism in the face of immense pressure. Her dispatches offered a window into a society grappling with profound moral and political questions, solidifying her reputation as a journalist of extraordinary courage and insight.

Read more about: Remember the ’70s? These Pivotal Moments and Transformations Mastered the Global Scene and Shaped Our World Forever.

7. **Intense Pressures and Surveillance Under Apartheid**As Ruth Weiss solidified her reputation as an independent journalist, the political climate in South Africa grew increasingly repressive. The government’s escalating response to anti-apartheid movements created an environment of intense pressure and constant surveillance for those who dared to question the regime, particularly journalists and their liberal-minded friends. The pervasive fear and scrutiny meant that every action, every conversation, carried potential risks.

Ms. Weiss herself offered vivid recollections of this chilling atmosphere, a stark contrast to the freedom of expression she inherently believed in. She chronicled how daily life was subtly but significantly altered by the omnipresent threat of the Special Branch, South Africa’s secret police. These were not abstract worries but tangible adjustments to personal conduct, necessary precautions to navigate a hostile state.

“I never parked in front of certain houses,” she wrote, illustrating the careful calculus required to avoid drawing unwanted attention to herself or others deemed dissidents. This simple act of choosing a parking spot became a loaded decision, reflecting the constant vigilance demanded of those who stood against the apartheid system. It underscored the insidious nature of state control, reaching into the most mundane aspects of existence.

Her memories also captured the chilling impact on communication. “Telephone calls were kept short and to the point,” she noted, indicating a profound erosion of privacy and open discourse. Furthermore, the vibrant social life that once characterized Johannesburg’s liberal circles had vanished: “The multiracial parties of the fifties were a thing of the past.” This curtailment of personal freedoms and social interaction painted a grim picture of a society under siege, where dissent was not only criminalized but actively suppressed through fear and isolation.

8. **A Clandestine Encounter with Nelson Mandela**Amidst this backdrop of state surveillance and repression, Ruth Weiss had an extraordinary, clandestine encounter that underscored the clandestine nature of the anti-apartheid struggle. She recounted meeting none other than Nelson Mandela himself, at a time when he was operating underground, a fugitive from the very system she so vehemently opposed. It was a moment that etched itself into her memory, a powerful symbol of the resistance against overwhelming odds.

Her recollection detailed the unexpected circumstances of this meeting. “I was having dinner at a friend’s house when her cook came in and whispered something to her,” Ms. Weiss wrote. This hushed exchange immediately signaled the sensitive and secretive nature of the situation, hinting at the dangerous reality of sheltering political activists during the apartheid era. The ordinary setting of a dinner party became a temporary sanctuary for a man hunted by the state.

Her friend, acting quickly and discreetly, excused herself from the table. She returned moments later, asking Ms. Weiss for assistance in the kitchen. There, in a seemingly innocuous domestic space, sat a figure who would become one of the 20th century’s most iconic freedom fighters. “A large man was sitting at the table, enjoying a plate of soup. He smiled at us,” Ms. Weiss recounted, capturing a rare moment of humanity and calm amidst intense political turmoil.

The identity of the visitor was then revealed: “Nelson Mandela. At that time he was on the run.” This direct, unvarnished statement highlighted the immense personal risk Mandela undertook daily, and by extension, the courage of those who aided him. For Ms. Weiss, whose life was dedicated to documenting and exposing injustice, this direct interaction with the embodiment of the resistance must have profoundly reinforced her resolve.

9. **Unwavering Opposition and Reporting in Rhodesia**As the political situation in South Africa became increasingly precarious for Ms. Weiss and her liberal associates, a new professional opportunity arose. In 1966, following the birth of her son, she was offered a position by The Financial Mail as bureau chief in Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia, which is now known as Harare, Zimbabwe. With the apartheid regime’s grip tightening in South Africa, she readily accepted this new assignment, viewing it as a necessary and timely move to continue her vital journalistic work in a different, albeit still challenging, context.

However, her time in Southern Rhodesia was also marked by confrontation with authority. The country, under Prime Minister Ian Smith, had unilaterally declared its independence from Britain, leading to crippling United Nations-imposed sanctions. Ms. Weiss, ever the astute economic journalist, quickly focused her reporting on the Smith government’s strenuous efforts to evade these sanctions, a topic of critical international importance and local sensitivity. Her investigations soon put her directly at odds with the ruling powers.

Her commitment to journalistic integrity transcended personal convenience or safety. She recognized the immense significance of exposing the sanctions evasion, a story that she felt compelled to pursue once she received tips from several businessmen. “As an economic journalist, I could not simply let it go,” she wrote, underscoring her professional imperative. “I had to find out what was happening.” This dedication to truth-telling, even when it promised severe repercussions, was a defining characteristic of her career.

Indeed, Ms. Weiss’s unwavering opposition to injustice was not merely a professional stance; it was a deeply ingrained personal conviction, one that predated her formal entry into journalism. She had famously confronted her employer at an insurance company, a nationalist Afrikaner, stating unequivocally: “I don’t like your system. I think it’s unjust and must be abolished.” This steadfast moral courage informed all her reporting, making her a formidable adversary to oppressive regimes wherever she encountered them.

10. **Expulsion from Rhodesia and Exile in London**The consequences of Ruth Weiss’s fearless reporting on sanctions evasion in Southern Rhodesia were swift and severe, underscoring the dangers inherent in challenging authoritarian governments. By 1968, her critical journalism had led directly to her expulsion from the country, forcing her to once again uproot her life and seek refuge abroad. It was a testament to the power of her investigative work that the government felt compelled to silence her.

Her career path was irrevocably altered by this turn of events. Leaving Rhodesia, Ms. Weiss relocated to London, where she promptly secured a position at The Guardian newspaper. This transition marked another significant chapter in her life of exile, but it did not diminish her resolve or her commitment to reporting on African affairs, even from afar. She adapted to her new circumstances, continuing to lend her authoritative voice to global events.

The official decree forbidding her return was unequivocal and chilling. “I received the order forbidding my entry with the threat of instant arrest if I as much as set a foot on Rhodesian soil while I was working at The Guardian,” she wrote. This explicit threat highlighted the government’s determination to prevent her from continuing her work and underscored the personal sacrifices demanded by her journalistic integrity. Her reporting had been too incisive, too effective, to be tolerated.

This expulsion from Rhodesia, coming after her earlier departure from Nazi Germany and the intense pressures she faced in apartheid South Africa, solidified her identity as a journalist perpetually on the front lines of injustice. It was a painful personal cost, severing her direct connection to the African continent for a time, but it also cemented her reputation as a principled and courageous reporter willing to endure hardship for the truth. Her exile became another chapter in her lifelong journey as a witness.

11. **A Prolific Later Life: Writing, Training, and Global Witness**Despite the adversities she faced, Ruth Weiss’s career remained remarkably prolific and geographically wide-ranging in her later decades. Following her stint at The Guardian in London, she returned to Africa in 1970, accepting a role as business editor of The Times of Zambia. This move allowed her to re-engage directly with the continent she had so passionately chronicled, bringing her expertise to a newly independent nation striving for economic development and stability.

Five years later, in 1975, Ms. Weiss transitioned to Germany, a country she had fled as a child. There, she served as the Africa expert at Deutsche Welle in Cologne, leveraging her deep knowledge and experience to provide informed analysis of African affairs to a European audience. By the late 1970s, she was back in London, embarking on a successful career as a freelance journalist, continuing to contribute to various publications with her insightful reporting.

The 1980s saw her return to Zimbabwe, where she played a crucial role in training journalists in the newly independent nation. During this period, she bore witness to Robert Mugabe’s ascent to power, first as prime minister and later as president, adding another complex political transition to her vast reportorial experience. She also co-founded the Zimbabwe Institute of Southern Africa, a vital discussion forum intended to prepare the country for the eventual end of apartheid, which met at Cold Comfort Farm outside Harare.

Her passion for writing extended beyond journalism. Throughout much of the 1990s, Ms. Weiss lived on the Isle of Wight in England, dedicating herself to penning novels, children’s books, and numerous works of non-fiction. Her published books translated into English include “Zimbabwe and the New Elite” (1994), “Sir Garfield Todd and the Making of Zimbabwe” (1999) with Jane Parpart, and “Peace in their Time: the Peace Process in Northern Ireland and Southern Africa” (2000), showcasing the breadth of her intellectual curiosity and her enduring commitment to understanding geopolitical struggles.

Read more about: Michel Odent: A Visionary Obstetrician’s Legacy in Natural Childbirth

12. **Enduring ‘Witness to History’ and Global Reflections on Prejudice**In her final decades, Ruth Weiss’s unique life trajectory and profound experiences transformed her into a highly sought-after lecturer in Germany. She was recognized as a “Zeitzeugin,” a powerful German term meaning “witness to history,” a designation that underscored her invaluable firsthand testimony regarding some of the 20th century’s most defining struggles against human rights abuses. Her voice became a crucial bridge between past traumas and present understanding, ensuring that the lessons of history were not forgotten.

Ms. Weiss’s reflections culminated in a universal indictment of prejudice, drawing on her lived experiences from Nazi Germany, apartheid South Africa, and Rhodesia. Addressing the state Parliament of North Rhine-Westphalia in Germany in 2023, she delivered a concise yet profoundly impactful statement that encapsulated her lifelong moral crusade: “Racism, antisemitism and misanthropy know no borders. These are injustices that must be fought everywhere.” This powerful declaration serves as an enduring testament to her conviction that the fight against discrimination is a global, continuous imperative.

Her formidable intellect, political acumen, and courage to take risks were lauded by Nobel Prize-winning novelist Nadine Gordimer, who wrote in the introduction to Ms. Weiss’s memoir, “A Path Through Hard Grass,” that she was “the most humane woman I have ever met.” This praise from a literary giant underscored not only Ms. Weiss’s professional achievements but also her profound moral character and unwavering empathy for those who suffered under oppressive systems.

Ruth Weiss’s extraordinary journey, from a child refugee fleeing Nazism to an intrepid journalist challenging apartheid and colonialism, left an indelible mark on global consciousness. She lived a life of purpose, constantly observing, documenting, and fighting against injustice in all its forms. She is survived by her son, Alexander, whom she joined in Aalborg in 2015, and a grandson, ensuring that her remarkable story and legacy continue to inspire future generations to uphold the values of truth, justice, and human dignity.

Read more about: Bucket List Cinema: 14 Certified Fresh Movies You Absolutely MUST See Before You Kick the Bucket

Ruth Weiss’s passing marks not merely the end of a long life but the culmination of a powerful narrative—one that, through its unyielding pursuit of truth across continents and decades, illuminates the enduring human struggle against prejudice and the indispensable role of journalism in holding power to account. Her legacy is not just in the words she penned, but in the unwavering moral compass that guided her every endeavor, reminding us all that vigilance against injustice is a perpetual calling.