In the annals of history, few names resonate with the intellectual and artistic grandeur of the Renaissance quite like Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci. A true titan of his era, Leonardo was not merely an artist; he was an Italian polymath, an individual whose boundless curiosity and prolific output spanned an astonishing array of disciplines. From the delicate strokes of a painter’s brush to the intricate schematics of an engineer, his work collectively constitutes a contribution to human understanding and aesthetic achievement matched only by a select few.

His legacy, however, is not simply defined by the sheer volume or diversity of his endeavors, but by the profound depth of his empirical thinking and the innovative spirit that infused every aspect of his creations. Long after his passing, his achievements, diverse interests, and personal life continue to captivate and inspire, marking him as a frequent subject of admiration and study. We are invited to delve into the meticulously crafted world of a genius, whose vision transcended the confines of his time and continues to illuminate our own.

This journey will not only celebrate his renowned artistry but also highlight the less visible, yet equally significant, facets of his intellect. We will explore the various spheres in which he excelled, the groundbreaking works that cemented his artistic immortality, and the extraordinary conceptual designs that underscore his role as a technological pioneer. Prepare to be immersed in the mind of a master, whose elegant solutions and aesthetic sensibilities redefined what was possible.

1. **The Polymathic Genius: Epitome of the Renaissance Ideal**Leonardo da Vinci, properly named Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci, was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance, active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. Born on 15 April 1452, he epitomized the Renaissance humanist ideal, a testament to an era that celebrated the potential and achievements of humanity. His collective works and diverse interests have incited interest and admiration since his death, cementing his place as one of history’s most compelling figures.

While his fame initially rested on his achievements as a painter, his notebooks reveal the true breadth of his genius. These invaluable records contain drawings and notes on a vast array of subjects, including anatomy, astronomy, botany, cartography, painting, and palaeontology. They serve as a window into a mind constantly observing, questioning, and theorizing, illustrating a profound engagement with the natural world and the mechanics of existence.

His education, though basic and informal in writing, reading, and mathematics, was likely redirected early due to the recognition of his artistic talents. This early focus allowed him to develop the broad technical skills acquired in Andrea del Verrocchio’s workshop, encompassing drafting, chemistry, metallurgy, and mechanics, alongside painting and sculpting. This foundational experience would later inform his interdisciplinary approach to every challenge he encountered.

Leonardo’s capacity to seamlessly integrate artistic expression with scientific inquiry is a hallmark of his polymathic approach. He saw no strict division between the two, instead viewing them as complementary paths to understanding the world. This holistic perspective allowed him to imbue his art with an unprecedented level of realism and his scientific observations with an artist’s eye for detail, truly setting him apart as a universal genius.

2. **The Master Painter: Founding the High Renaissance**Leonardo is unequivocally identified as one of the greatest painters in the history of Western art and is often credited as the founder of the High Renaissance. Despite a notable number of lost works and fewer than 25 attributed major pieces – many of which remained unfinished – he created some of the most profoundly influential paintings in the Western canon. His artistic output, though limited in quantity, is unparalleled in its quality and impact, shaping the trajectory of art for centuries to come.

His mastery was evident from his earliest collaborations, such as with Verrocchio on ‘The Baptism of Christ’, where Leonardo’s skill in painting the young angel was purportedly so superior that his master never painted again. This early indication of his prodigious talent foretold the revolutionary changes he would bring to painting, introducing new techniques and a depth of realism previously unseen. His artistic innovations were not just technical; they conveyed profound emotional and psychological insights.

Florence, the vibrant center of Christian Humanist thought, provided the fertile ground for his artistic development. Exposed to the works of masters like Masaccio and Ghiberti, and influenced by Piero della Francesca’s scientific study of light and perspective, Leonardo absorbed and then transcended the prevailing artistic conventions. His work profoundly impacted younger artists, laying the groundwork for the High Renaissance’s emphasis on harmony, balance, and humanism.

His paintings are celebrated for innovative techniques in laying on paint, a detailed knowledge of anatomy, light, botany, and geology, and a keen interest in physiognomy and the way humans convey emotion through expression and gesture. These qualities, combined with his innovative use of the human form in figurative composition and subtle gradation of tone, converged in masterpieces like the ‘Mona Lisa’, ‘The Last Supper’, and ‘The Virgin of the Rocks’, demonstrating an artistic vision far ahead of his contemporaries.

Read more about: Rosalyn Drexler: A Polymath’s Legacy – Unpacking the Diverse Chapters of an Artistic Whirlwind Who Defied Categorization

3. **Iconic Masterpieces: The Mona Lisa’s Elusive Enchantment**Among the works created by Leonardo in the 16th century, the small portrait known as the ‘Mona Lisa’, or ‘La Gioconda’, stands preeminent. In the present era, it is arguably the most famous painting in the world, a status earned not merely by its historical significance, but by an enduring enigmatic quality that continues to mesmerize viewers. The portrait began its life in 1503, portraying Lisa del Giocondo, and Leonardo continued to refine it into his later years.

Its unparalleled fame rests, in particular, on the elusive smile on the woman’s face, a mysterious quality perhaps due to the subtly shadowed corners of the mouth and eyes, rendering the exact nature of the smile impossible to determine. This masterful technique of blending tones, where the transitions from light to shadow are imperceptible, came to be known as sfumato, or ‘Leonardo’s smoke’. Vasari eloquently captured its essence, writing that the smile was “so pleasing that it seems more divine than human, and it was considered a wondrous thing that it was as lively as the smile of the living original.”

Beyond the smile, the painting’s other characteristics contribute to its profound allure. The unadorned dress directs all attention to the eyes and hands, unburdened by competing details. The dramatic landscape background, seemingly in a state of flux, adds to the dreamlike quality. Furthermore, the subdued coloring and the extremely smooth painterly technique, achieved by laying oils much like tempera and blending them seamlessly, make the brushstrokes indistinguishable, a feat that Vasari believed would make even “the most confident master … despair and lose heart.”

The remarkable state of preservation of the ‘Mona Lisa’, with no sign of repair or overpainting, is rare for a panel painting of its antiquity. This pristine condition allows contemporary audiences to experience the work almost as Leonardo intended, a direct connection to his genius. It is a testament to his meticulous craftsmanship and the innovative methods he employed, creating a work that transcends time and cultural boundaries to remain a global icon of art and mystery.

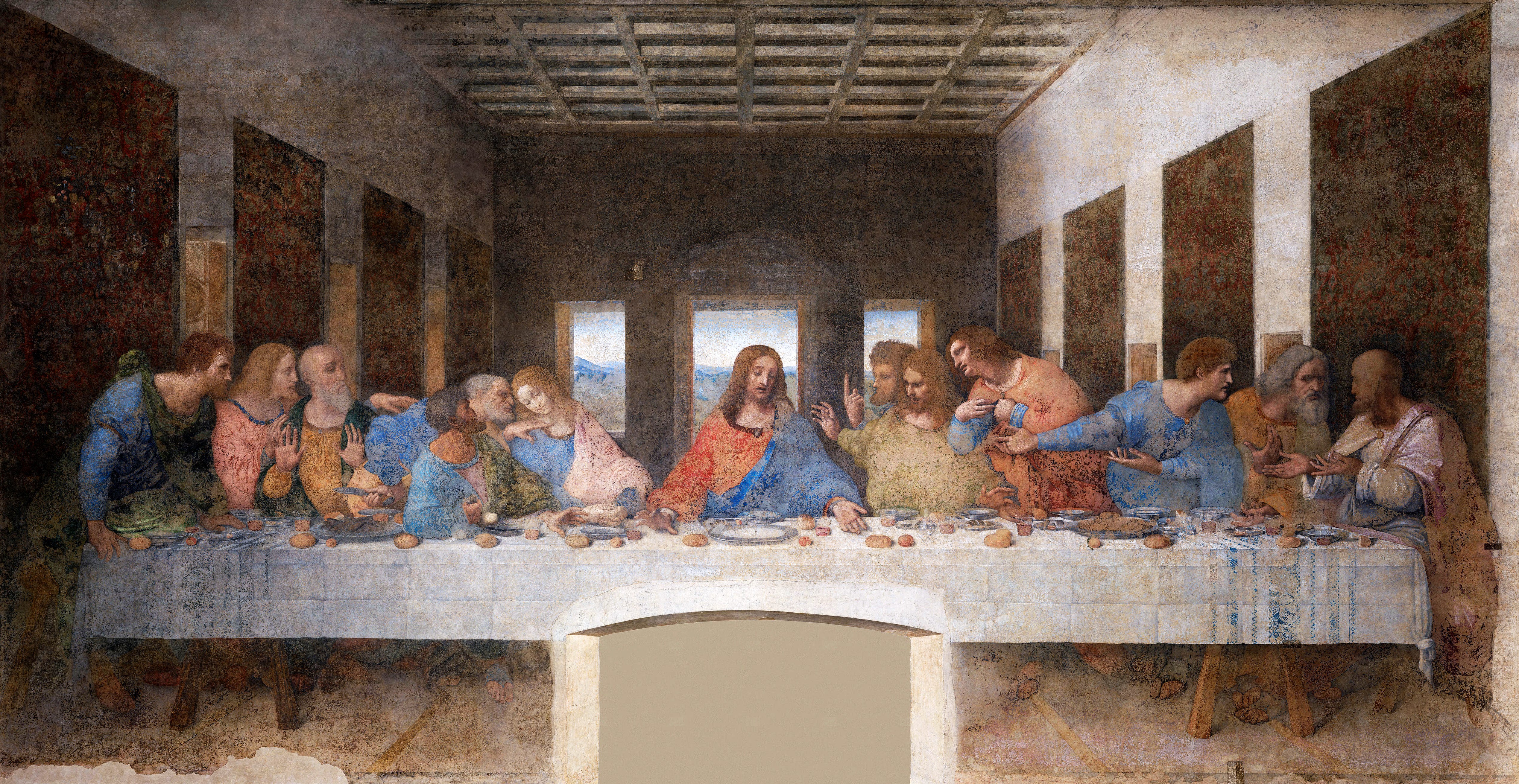

4. **Iconic Masterpieces: The Dramatic Narrative of The Last Supper**Leonardo’s most famous painting of the 1490s is ‘The Last Supper’, a monumental fresco commissioned for the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria della Grazie in Milan. This iconic work depicts the final meal shared by Jesus with his disciples before his capture and death, specifically capturing the profoundly dramatic moment when Jesus has just declared, “one of you will betray me,” and the resulting consternation that sweeps through the assembly. The composition is a masterclass in narrative tension and psychological realism.

The artist’s approach to this commission was uniquely dedicated, as observed by the writer Matteo Bandello, who noted Leonardo would sometimes paint from dawn till dusk without pause, only to then abstain from painting for three or four days. This unorthodox working method, driven by a deep engagement with the subject matter, perplexed the convent’s prior, necessitating the intervention of Duke Ludovico Sforza. Leonardo even confided in the duke that his struggle to adequately depict the faces of Christ and the traitor Judas might compel him to use the prior as his model, a testament to his commitment to psychological truth.

Despite being acclaimed as a masterpiece of design and characterization upon its completion, the painting began to deteriorate rapidly. Within a century, it was described by one viewer as “completely ruined.” This unfortunate degradation was a direct consequence of Leonardo’s experimental technique: instead of using the robust traditional fresco method, he applied tempera over a ground that was mainly gesso, making the surface highly susceptible to mould and flaking. His innovative spirit, while yielding profound artistic results, sometimes led to practical vulnerabilities.

Nonetheless, ‘The Last Supper’ remains one of the most reproduced works of art in history, inspiring countless copies across various mediums. Its powerful composition, the individual reactions of the disciples, and the central, serene figure of Christ continue to resonate, inviting contemplation on themes of faith, betrayal, and human emotion. Even in its deteriorated state, its artistic and emotional impact is undeniable, securing its place as an enduring symbol of spiritual and artistic achievement.

Read more about: The Million-Dollar Memories: Unveiling 15 Legendary Movie Props That Sold for Unbelievable Fortunes

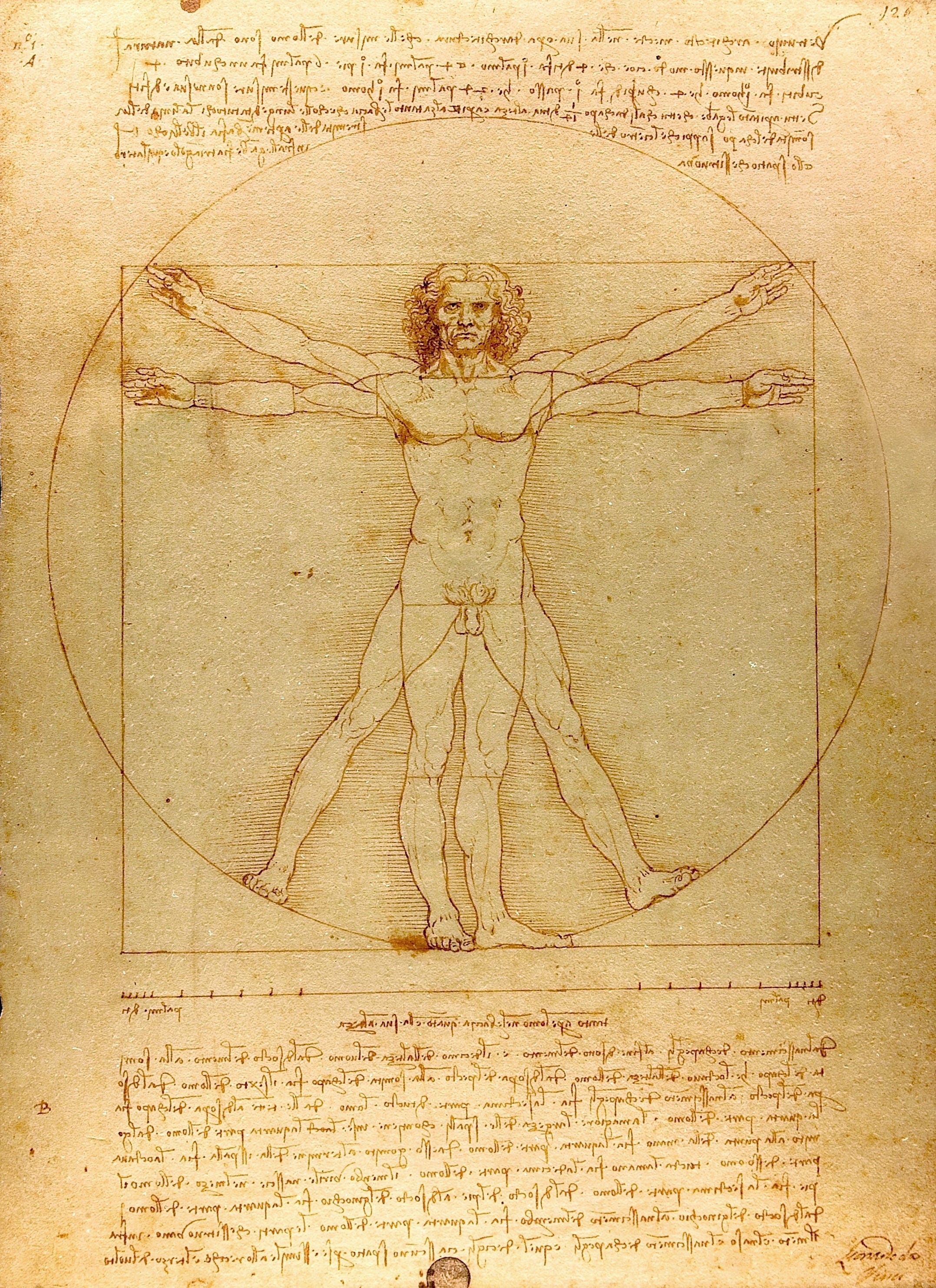

5. **The Vitruvian Man: A Synthesis of Art and Science**Beyond his celebrated paintings, Leonardo’s ‘Vitruvian Man’ drawing, created around 1485, stands as an indisputable cultural icon, recognized globally for its profound representation of the ideal human proportions and its symbolic fusion of art and science. This ink on paper drawing illustrates a man in two superimposed positions with his arms and legs apart and inscribed in both a circle and a square. It serves as a visual commentary on the theories of the Roman architect Vitruvius, whose ancient texts Leonardo studied with meticulous detail.

The drawing transcends a mere anatomical study; it is a profound philosophical statement about humanity’s place in the cosmos. It perfectly encapsulates Leonardo’s belief that the human body was a microcosm, reflecting the harmonious order and mathematical principles of the universe. The precise geometric forms—the circle representing the divine, and the square representing the earthly—interact with the human figure to create a dynamic equilibrium, showcasing his keen understanding of both biological function and abstract geometry.

This single image powerfully illustrates Leonardo’s interdisciplinary approach. It is an anatomical drawing, a mathematical diagram, and a philosophical treatise all rolled into one. His detailed knowledge of human anatomy, gleaned from his extensive dissections, is evident in the precise rendering of the musculature and skeletal structure. Simultaneously, his grasp of mathematics and architectural principles allows him to present Vitruvius’s ratios in a compelling and aesthetically pleasing manner, demonstrating the beauty inherent in scientific truth.

‘The Vitruvian Man’ has transcended its original purpose to become a universal symbol of humanism, rationality, and the Renaissance’s boundless intellectual curiosity. It signifies the perfect blend of art and scientific inquiry, a visual manifesto for Leonardo’s holistic vision of the world. Its enduring appeal lies in its elegant simplicity and the complex ideas it conveys, making it one of the most recognized and celebrated drawings in Western civilization.

6. **Technological Visionary: Engineering the Future**Revered for his technological ingenuity, Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks are a veritable treasure trove of conceptual designs that were centuries ahead of their time. He conceptualized flying machines, a type of armoured fighting vehicle, concentrated solar power, a ratio machine that could be used in an adding machine, and the double hull. These extraordinary inventions reveal a mind constantly pushing the boundaries of what was technologically feasible, envisioning solutions to problems that would only be tackled much later in history.

His engineering designs were not mere fanciful sketches; they were detailed plans, often accompanied by extensive notes and calculations. For instance, his flying machines, with their flapping wings and intricate gear systems, demonstrated a profound understanding of aerodynamics, even if the materials and power sources available in the Renaissance made their construction impossible. This meticulous approach speaks to his dual role as both a visionary and a practical problem-solver.

However, relatively few of his designs were constructed or even feasible during his lifetime. The modern scientific approaches to metallurgy and engineering were still in their infancy during the Renaissance, limiting the ability to translate his ambitious concepts into tangible realities. The technological infrastructure simply did not exist to support the sophistication of his ideas, leaving many of his grandest visions to remain on paper.

Despite these limitations, some of his smaller inventions subtly entered the world of manufacturing unheralded, such as an automated bobbin winder and a machine for testing the tensile strength of wire. These less glamorous but highly practical innovations underscore his versatile mind and his ability to address everyday challenges with ingenious solutions. His technological foresight, even when unfulfilled in his lifetime, profoundly influenced later generations of inventors and engineers.

Read more about: Unveiling Leonardo da Vinci: A Renaissance Titan’s Enduring Legacy Across Art, Science, and Engineering

7. **Scientific Discoveries: The Unseen Influence of His Findings**Leonardo da Vinci made substantial discoveries in a wide array of scientific fields, including anatomy, civil engineering, hydrodynamics, geology, optics, and tribology. His empirical approach, characterized by meticulous observation and detailed recording, led him to insights that anticipated many later scientific advancements. However, a crucial aspect of his scientific legacy is that he did not publish his findings, meaning they had little to no direct influence on subsequent science during his lifetime.

His anatomical studies, for example, involved the dissection of cadavers and resulted in hundreds of incredibly detailed drawings and notes. These went far beyond the superficial, exploring muscles, bones, organs, and even the vocal cords, for which he considered writing a treatise. Had these observations been published, they would have revolutionized the understanding of human anatomy centuries before Vesalius, showcasing a depth of knowledge that rivaled and sometimes surpassed contemporary medical science.

In civil engineering, his projects included devising methods to defend cities from naval attack, as seen during his time in Venice. For Cesare Borgia, he acted as a military architect and engineer, creating precise town plans and maps, such as the map of Imola and one of the Chiana Valley in Tuscany. He also conceptualized projects like constructing a dam from the sea to Florence to sustain a canal, demonstrating a sophisticated grasp of hydraulic principles.

His work in hydrodynamics involved detailed studies of water flow, eddies, and currents, captured in numerous drawings and analyses that reveal an intuitive understanding of complex fluid dynamics. Similarly, his geological observations of rock formations and fossils led him to conclusions about the age of the Earth and the processes that shaped its surface, challenging contemporary beliefs. His optics research delved into the nature of light and vision, further demonstrating his comprehensive scientific curiosity across diverse domains, leaving behind an unparalleled record of a mind deeply engaged with the mechanisms of the natural world, albeit a largely private one.” , “_words_section1”: “1945

8. **The Second Florentine Period (1500-1508): Reengagement and Architectural Endeavors**Returning to Florence in 1500 after Ludovico Sforza’s overthrow, Leonardo’s presence once again ignited artistic fervor. He and his household found hospitality with the Servite monks at Santissima Annunziata, where he was provided with a workshop. Here, he crafted the monumental cartoon of ‘The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and Saint John the Baptist,’ a work that, according to Vasari, drew such immense admiration that “men [and] women, young and old” flocked to see it “as if they were going to a solemn festival.” This period marked a powerful re-engagement with his Florentine roots, demonstrating his undiminished capacity to captivate and inspire.

His expertise soon led him into the service of powerful figures once more. In 1502, Leonardo joined Cesare Borgia, Pope Alexander VI’s son, as a military architect and engineer. This role saw him traveling across Italy with his patron, creating precise town plans and maps, such as the map of Imola and one of the Chiana Valley in Tuscany. These cartographic innovations provided Borgia with a superior strategic overlay of the land, showcasing Leonardo’s practical application of his scientific acumen to pressing contemporary needs. His projects extended to grand civil engineering, including conceptualizing a dam from the sea to Florence to ensure a consistent water supply for a canal, illustrating his sophisticated grasp of hydraulic principles.

By early 1503, Leonardo had returned to Florence, rejoining the Guild of Saint Luke. It was during this period that he commenced work on the ‘Mona Lisa,’ a portrait he would continue to refine for years, and which would eventually become the world’s most famous painting. He also took on a commission to design and paint a mural of ‘The Battle of Anghiari’ for the Signoria in the Palazzo Vecchio, a monumental task mirroring Michelangelo’s companion piece. These commissions highlight a phase of intense artistic production and civic engagement, reaffirming his standing as Florence’s foremost master, even amidst such esteemed contemporaries.

This era, rich with diverse commissions and personal projects, underscores Leonardo’s seamless transition between the roles of artist, engineer, and cartographer. His ability to apply his empirical thinking and innovative spirit to such varied challenges speaks volumes about the breadth of his intellect. Whether designing fortifications or capturing a fleeting smile, his approach remained meticulously detailed and profoundly transformative, marking this as a profoundly active and influential chapter in his illustrious career.

9. **Second Milanese Period (1508-1513): Artistic Circle and Engineering Ambitions**After his dynamic return to Florence, Leonardo once again found himself drawn to Milan by 1508, establishing his residence in Porta Orientale within the parish of Santa Babila. This second period in Milan witnessed him resuming various artistic and engineering pursuits, rekindling old connections, and fostering new ones within a vibrant artistic community. His reputation as a master continued to attract a considerable following, leading to the mentorship of several prominent pupils.

Among those who either knew or worked with him during this period were Bernardino Luini, Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, and most notably, Count Francesco Melzi. Melzi, the son of a Lombard aristocrat, quickly became regarded as Leonardo’s favorite student, a relationship that would evolve into a deep and lasting companionship. These pupils, often termed his “Milanese school,” absorbed Leonardo’s innovative techniques and philosophical approach, extending his influence through their own works. The nurturing of such talent showcases Leonardo’s generosity as a teacher and his impact on the next generation of Renaissance artists.

Amidst his teaching and ongoing artistic endeavors, Leonardo’s engineering ambitions persisted. In 1512, he dedicated his efforts to drafting plans for an elaborate equestrian monument intended for Gian Giacomo Trivulzio. This project, much like the earlier ‘Gran Cavallo’ for Francesco Sforza, was a testament to his continued fascination with monumental sculpture and his mastery of complex structural design. However, fate intervened once more; an invasion by a confederation of Swiss, Spanish, and Venetian forces drove the French from Milan, halting the project and preventing the realization of another of his grand visions.

Despite the political upheavals that often disrupted his work, Leonardo remained in Milan, even spending several months in 1513 at the Medici’s Vaprio d’Adda villa. This period, though marked by unfulfilled commissions, illustrates his unwavering commitment to both artistic creation and scientific exploration. His detailed studies and conceptual designs from this time, preserved in his notebooks, continue to inspire awe, reflecting a mind constantly in pursuit of both aesthetic perfection and mechanical ingenuity.

10. **Rome and Papal Patronage (1513-1516): A Period of Frustrated Creativity**In September 1513, following the election of Lorenzo de’ Medici’s son Giovanni as Pope Leo X, Leonardo traveled to Rome. He was received by the Pope’s brother, Giuliano, and spent the next three years living in the Belvedere Courtyard of the Apostolic Palace, a vibrant hub where esteemed artists like Michelangelo and Raphael were also active. This environment, however, did not prove to be as fruitful for Leonardo’s artistic output as one might expect, despite the prestige of his surroundings and a generous allowance of 33 ducats a month.

Curiously, a painting commission of unknown subject matter from the Pope was abruptly cancelled when Leonardo embarked on an experimental new kind of varnish. This incident highlights a recurring theme in his career: his insatiable curiosity and experimental spirit often superseded conventional expectations or commercial deadlines. His innovative methods, while leading to groundbreaking results in masterpieces like ‘The Last Supper’, sometimes introduced practical vulnerabilities or, as in this case, led to the abandonment of projects when traditional patrons expected predictable outcomes.

During his time in Rome, Leonardo also experienced illness, which may have been the first of multiple strokes that would eventually lead to his death. Despite these challenges, his intellectual pursuits remained undeterred. He immersed himself in botany within the Vatican Gardens, demonstrating his enduring fascination with the natural world. He was also commissioned to devise plans for the Pope’s ambitious project to drain the Pontine Marshes, a testament to his respected expertise in civil engineering and hydraulics, even when his artistic commissions faltered.

His anatomical studies also continued in Rome, involving the dissection of cadavers and the meticulous recording of notes for a treatise on vocal cords. These profound scientific endeavors, however, failed to regain the Pope’s favor when Leonardo attempted to present them. This period in Rome, though marked by prestigious patronage, appears to have been a complex blend of creative frustration, health challenges, and continued, largely private, scientific inquiry, underscoring the universal genius’s struggle to align his boundless curiosity with the demands of his patrons.

11. **The French Court at Clos Lucé (1516-1519): Final Honors and Declining Health**Following the recapture of Milan by King Francis I of France in October 1515, Leonardo’s talents drew the attention of the French monarch. By March 1516, Francis I had extended an invitation for Leonardo to relocate to France, eager to welcome the esteemed artist to his court. Later that year, Leonardo entered Francis’s service, receiving the comfortable manor house Clos Lucé, conveniently located near the King’s residence at the royal Château d’Amboise. This marked a profound shift, offering Leonardo a period of esteemed patronage and relative tranquility during his final years.

King Francis I frequently visited Leonardo, a testament to the profound respect and admiration he held for the aging master. During this time, Leonardo drew plans for an immense castle town that the King intended to erect at Romorantin, showcasing his continued architectural prowess on a grand scale. His inventive spirit also found expression in more spectacular creations, such as a mechanical lion designed for a royal pageant. This marvel walked towards the King and, upon being struck by a wand, opened its chest to reveal a cluster of lilies, symbolizing the French monarchy. These projects demonstrate that even in his later years, Leonardo’s mind remained keenly engaged with ambitious designs and imaginative constructions.

Throughout this final chapter, Leonardo was accompanied by his loyal friend and apprentice, Francesco Melzi, who played a crucial role in his life and work, and was supported by a substantial pension totaling 10,000 scudi. Melzi himself created a portrait of Leonardo during this time, one of the few known from his lifetime, alongside sketches by an unknown assistant and a drawing by Giovanni Ambrogio Figino. The latter depicts an elderly Leonardo with his right arm wrapped in clothing, an observation corroborated by a record of a 1517 visit by Louis d’Aragon, which confirms that Leonardo’s right hand had become paralytic when he was 65.

This physical affliction may shed light on why some of his works, including the ‘Mona Lisa’, remained unfinished, as he continued to work at some capacity until eventually becoming ill and bedridden for several months. Despite the challenges of declining health, his final years in France were characterized by royal esteem, continued intellectual engagement, and the close companionship that allowed him to pursue his interests until his passing, leaving behind a profound personal and artistic legacy within the luxurious setting of the French court.

12. **Private Life and Public Speculation: The Human Element of a Genius**Despite the thousands of pages Leonardo left in his voluminous notebooks and manuscripts, he rarely delved into the intricacies of his personal life, maintaining a remarkable privacy. Yet, within his lifetime and for centuries thereafter, the “extraordinary powers of invention,” his “great physical beauty,” and “infinite grace,” as described by Vasari, alongside every other aspect of his existence, naturally ignited intense curiosity. This extended to his noted love for animals, which likely underpinned his vegetarianism and his reported habit of purchasing caged birds merely to set them free, revealing a compassionate dimension to his character.

Leonardo cultivated many significant friendships with notable figures of his era, including the esteemed mathematician Luca Pacioli, with whom he collaborated on the influential book ‘Divina proportione’ in the 1490s. While he appears to have had no intimate relationships with women beyond friendships, such as those with Cecilia Gallerani and the Este sisters, Beatrice and Isabella, these connections were deeply valued. His drawing of Isabella d’Este during a journey through Mantua exemplifies these bonds, suggesting a keen appreciation for intellectual and artistic companionship over romantic entanglement.

However, beyond these friendships, Leonardo guarded his private life with great discretion, particularly concerning his uality. This aspect has been a consistent subject of satire, analysis, and intense speculation, a trend that began in the mid-16th century and was notably revived by Sigmund Freud in the 19th and 20th centuries. His most intimate relationships are widely considered to have been with his pupils, Salaì and Francesco Melzi. Melzi, in a poignant letter informing Leonardo’s brothers of his death, described the master’s feelings for his pupils as both loving and passionate, hinting at the depth of these bonds.

Since the 16th century, claims have persisted regarding the ual or erotic nature of these relationships. Court records from 1476 reveal that Leonardo, then twenty-four, along with three other young men, was charged with sodomy in connection with a known male prostitute. Though the charges were dismissed due to a lack of evidence, speculation has suggested that the influence of the powerful Medici family, to whom one of the accused was related, played a role in the dismissal. This incident, along with the nuanced portrayal of androgyny and eroticism in works such as ‘Saint John the Baptist’ and ‘Bacchus’, and certain explicit erotic drawings, has significantly fueled ongoing discussions about his presumed homosexuality and its subtle, yet profound, role in his art.

Walter Isaacson, in his biography of Leonardo, makes an explicit assertion regarding the intimate and homoual nature of his relations with Salaì. Such analyses underscore the enduring fascination with Leonardo’s inner world, inviting us to contemplate how his personal experiences and emotional landscape might have subtly shaped the profound psychological depth and enigmatic beauty that defines much of his immortal oeuvre, forever intertwining the man with the mystery of his art.

13. **Synthesizing Genius: The Holistic Impact of His Artistic Innovations**While specific artistic techniques such as sfumato or chiaroscuro are often highlighted, Leonardo’s true genius lay in his ability to synthesize a multitude of observations and intellectual pursuits into a coherent and revolutionary artistic style. He didn’t just employ techniques; he embodied a holistic approach to painting that fundamentally transformed the art world. His works are celebrated for an unprecedented blend of observational science and profound humanism, where every brushstroke was informed by an intricate understanding of the natural and emotional world, cementing his status as a “Divine” painter.

His detailed knowledge of anatomy, gleaned from extensive dissections, allowed him to render the human form with unparalleled realism and accuracy, from musculature to skeletal structure. This scientific rigor was complemented by an acute interest in physiognomy and the subtle ways humans convey emotion through expression and gesture. This fusion enabled him to imbue his figures with a psychological depth and lifelike presence that was groundbreaking, making his portraits and narrative scenes resonate with an authentic human spirit that transcended mere representation.

Furthermore, Leonardo’s profound studies in light, botany, and geology profoundly influenced his landscape backgrounds and his overall handling of atmosphere. The “dramatic landscape background, in which the world seems to be in a state of flux” in the ‘Mona Lisa’, or the “wild landscape of tumbling rock and whirling water” in ‘The Virgin of the Rocks’, are not merely backdrops but active, contributing elements that enhance the emotional and narrative power of his compositions. His command of subtle gradation of tone, achieved through innovative layering of oils, made his brushstrokes indistinguishable and created a seamless, almost ethereal quality, which Vasari believed would make even “the most confident master … despair and lose heart.”

Ultimately, Leonardo’s innovative use of the human form in figurative composition, combined with his unparalleled command of tone and atmospheric perspective, converged to create masterpieces that were not only visually stunning but also intellectually provocative and emotionally resonant. His art became a mirror reflecting the harmonious order and mathematical principles he perceived in the universe, an elegant synthesis of art and scientific inquiry. This unified vision solidified his unparalleled legacy, shaping the trajectory of the High Renaissance and establishing a standard of excellence that continues to inspire and challenge artists and thinkers alike.

14. **The Enduring Echoes of a Universal Mind: Legacy and Reverence**Leonardo da Vinci passed away at Clos Lucé on May 2, 1519, at the age of 67, likely from a stroke. His death brought an end to an era of unparalleled intellectual and artistic exploration, leaving behind a legacy that would echo through centuries. King Francis I, who had become a close friend and admirer, reputedly held Leonardo’s head in his arms as he died, a testament to the profound respect the monarch held for the genius. While this story may be legendary, it perfectly encapsulates the reverence with which Leonardo was regarded in his final days.

In accordance with his meticulously planned will, Francesco Melzi, his loyal friend and apprentice, was named the principal heir and executor. Melzi inherited Leonardo’s invaluable paintings, tools, an extensive library, and personal effects, becoming the custodian of a lifetime of work and thought. Leonardo’s other long-time pupil and companion, Salaì, and his servant, Baptista de Vilanis, each received half of his vineyards, while his brothers received land, and his serving woman a fur-lined cloak. This careful distribution ensured that those closest to him were remembered, while the core of his intellectual and artistic property was entrusted to the one most capable of preserving it.

Some two decades after Leonardo’s passing, the renowned goldsmith and sculptor Benvenuto Cellini reported King Francis I as proclaiming, “There had never been another man born in the world who knew as much as Leonardo, not so much about painting, sculpture and architecture, as that he was a very great philosopher.” This poignant appraisal from a king who had witnessed Leonardo’s genius firsthand articulates the breadth of his impact, acknowledging him not just as a master artist but as a profound thinker whose understanding transcended conventional disciplinary boundaries.

Indeed, since his death, there has never been a period when Leonardo’s achievements, his diverse interests, his complex personal life, and his rigorous empirical thinking have failed to incite interest and admiration. He remains a frequent subject of study and inspiration, a universal genius whose curiosity continues to illuminate our understanding of art, science, and the boundless potential of the human mind. His unparalleled legacy is not merely in the works he completed, but in the enduring spirit of inquiry and the harmonious integration of knowledge that he so eloquently championed, forever marking him as one of history’s most compelling and influential figures.

From the delicate strokes that brought the Mona Lisa to life to the audacious designs for flying machines, Leonardo da Vinci’s journey was one of perpetual discovery and creation. He was a man who truly saw the interconnectedness of all things, whose meticulous observations of the natural world were woven into the very fabric of his art, and whose visionary mind constantly pushed the boundaries of human knowledge. His story is not just a chronicle of masterpieces, but an enduring testament to the power of curiosity and the timeless beauty that emerges when art and science embrace.