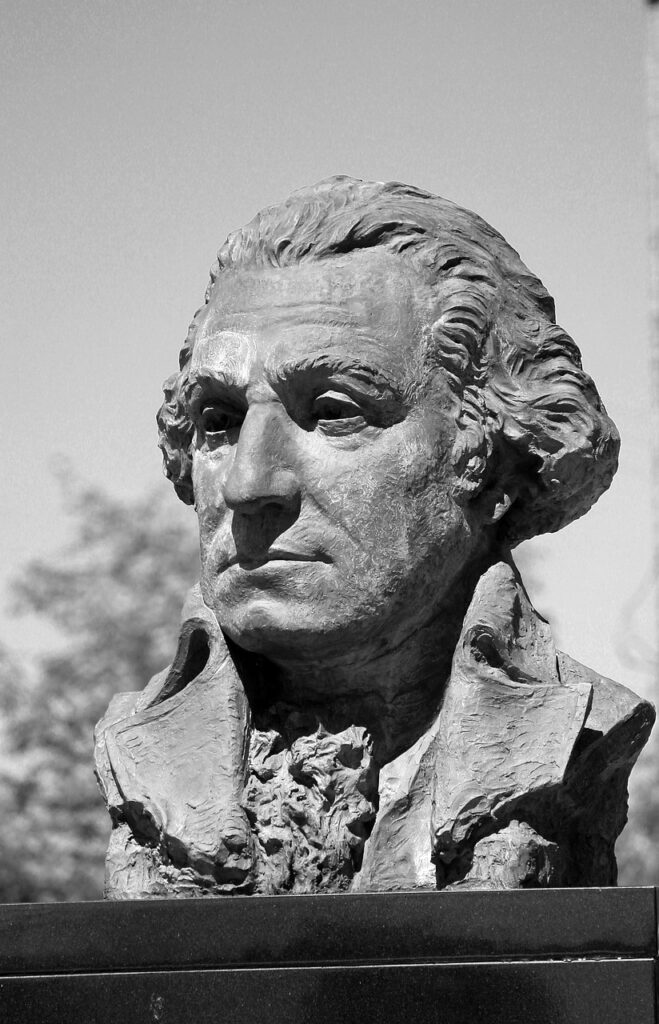

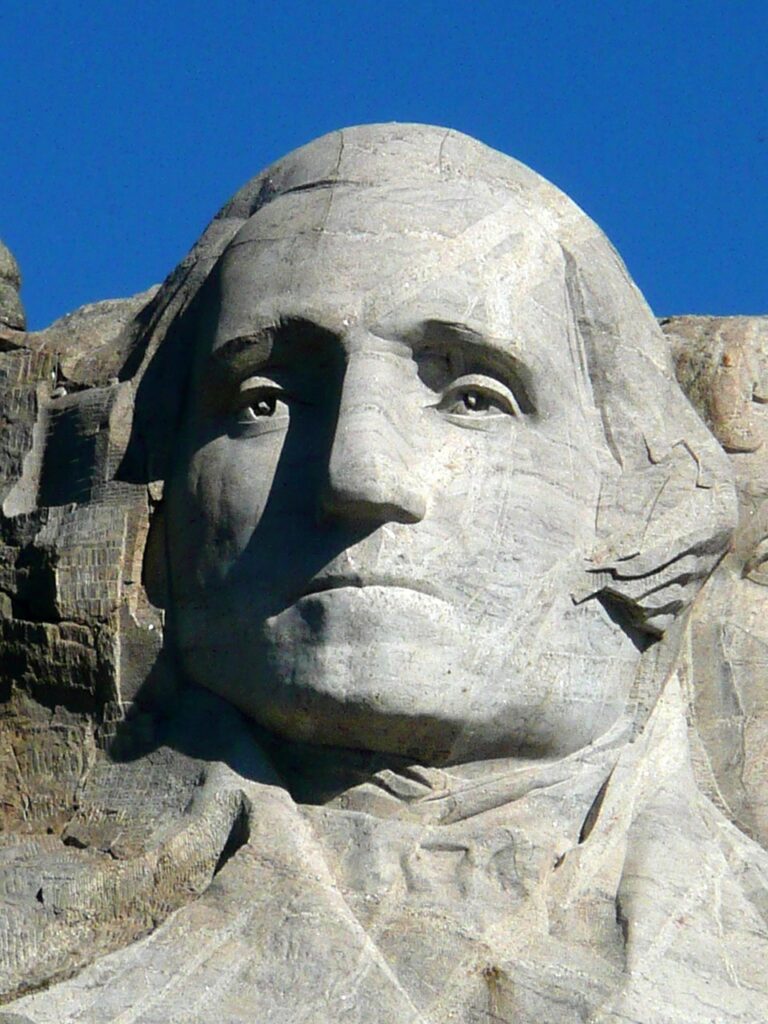

In the grand tapestry of American history, few figures loom as large as George Washington. He is often presented as the stoic, mythical Father of the Nation, his image gracing our currency and monuments. Yet, beneath this unblemished facade, lay a man shaped by profound challenges, critical decisions, and the brutal realities of a nascent nation struggling for identity.

To truly understand Washington’s enduring legacy requires a deep dive into the crucible of his experiences. It’s a narrative not merely of triumph, but of perseverance through setback, of ambition tempered by duty, and of a relentless pursuit of independence. His journey was a masterclass in leadership, demonstrating how character is forged in the fiery heat of conflict and uncertainty. Join us as we explore the pivotal chapters that defined him, illuminating why George Washington remains the indispensable man.

1. **A Formative Youth in Colonial Virginia**George Washington was born February 22, 1732, at Popes Creek, Virginia, the first of six children of Augustine and Mary Ball Washington. His early years contrasted with the formal education his elder half-brothers received, a direct result of his father’s death in 1743. This circumstance, coupled with a “fractious relationship” with his mother, meant Washington’s development focused on practical skills rather than academic pursuits.

Despite lacking elite schooling, Washington’s ambition led him to master mathematics and land surveying. He became a talented draftsman and mapmaker, his precision hinting at a mind capable of meticulous planning. As a teenager, he compiled “The Rules of Civility,” over a hundred rules for social interaction, revealing an early understanding of public conduct that would later define him.

The influence of William Fairfax, his half-brother Lawrence’s father-in-law and Washington’s patron, was crucial. Fairfax provided guidance, even appointing him surveyor of Culpeper County in 1749. By 1752, Washington had acquired almost 1,500 acres. His only trip outside mainland North America was to Barbados in 1751, where he contracted smallpox. Lawrence’s death in 1752 eventually led Washington to inherit Mount Vernon, establishing him as a significant Virginia planter.

Read more about: Quincy, Massachusetts: A Storied Legacy of Presidents, Pioneers, and Enduring American Spirit

2. **Forging a Military Identity: The French and Indian War**Inspired by Lawrence’s service, Washington secured a militia commission from Lieutenant Governor Robert Dinwiddie, becoming a major and district commander. This period, marked by British-French rivalry over the Ohio River Valley, thrust Washington into early continental conflict. His first significant mission in October 1753 was as a special envoy, demanding French forces vacate British-claimed land and gathering intelligence.

Washington’s report on this arduous winter journey to Fort Le Boeuf, detailing the French refusal, earned him distinction upon its publication. However, his subsequent promotion to lieutenant colonel and orders to confront the French led to the “Jumonville affair.” In May 1754, Washington commanded an ambush, resulting in the death of French commander Joseph Coulon de Jumonville. The French blamed Washington, a charge intensified by his unwitting signing of a surrender document at Fort Necessity, which held him responsible for “assassinating” Jumonville.

The Battle of Fort Necessity culminated in Washington’s surrender to a superior French force, a humbling experience. This, along with a demotion offer, prompted his resignation. This early military career, though controversial, was profoundly formative. It ignited the French and Indian War and exposed Washington to frontier warfare’s brutal realities, complex command structures, and high stakes imperial rivalries, instilling crucial leadership skills.

3. **Redemption and Reappointment: Lessons from Braddock’s Defeat**Despite early military frustrations, Washington’s ambition remained. In 1755, he volunteered as an aide to General Edward Braddock, leading a British expedition to expel the French from Fort Duquesne. This offered Washington a crucial opportunity to observe professional British military operations, contrasting with his colonial militia command.

The expedition met disaster at the Battle of the Monongahela. Ambushed by French and Indian allies, the British suffered devastating casualties, including General Braddock. Washington, despite severe dysentery and having two horses shot, displayed extraordinary courage. He rallied survivors and formed a rear guard, preventing a complete rout. This bravery, under harrowing circumstances, significantly redeemed his reputation, previously tarnished by Fort Necessity.

His conduct at Monongahela re-established his standing, demonstrating resilience and decisive action. Yet, the experience also highlighted British military condescension towards “colonials,” as Washington was excluded from planning subsequent operations. This fueled his growing hostility toward British policies. The crucible of Braddock’s defeat taught Washington invaluable lessons in command, logistics, and fighting in American wilderness terrain.

4. **Mount Vernon and the Planter’s Life: Wealth, Land, and Marriage**Following his colonial military service, Washington transitioned into a chapter of domesticity and economic prosperity. On January 6, 1759, at age 26, he married Martha Dandridge Custis, a 27-year-old wealthy widow. Martha was intelligent, gracious, and experienced in estate management, contributing to their happy marriage. Their union significantly elevated Washington’s financial standing and social prestige in Virginia.

The marriage gave Washington control over Martha’s one-third dower interest in the 18,000-acre Custis estate, and he managed the remaining two-thirds for her children. This instantly made him one of Virginia’s wealthiest men, providing an economic foundation for his ambitions. Residing at Mount Vernon, which he inherited in 1761, Washington dedicated himself to planter life, cultivating tobacco and wheat, and overseeing a growing enslaved population that more than doubled by 1775.

Washington actively sought to expand his holdings. He engaged surveyor William Crawford to subdivide lands in the Ohio and Great Kanawha regions, acquiring 23,200 acres. By the mid-1760s, facing debt from spending and low tobacco prices, he made a pivotal economic shift. He diversified Mount Vernon’s primary cash crop from tobacco to wheat, and expanded into flour milling and hemp farming, seeking greater independence from London merchants. This period underscored his pragmatic approach to wealth.

5. **A Colonial Voice of Dissent: Opposition to British Policies**As a respected military hero and large landowner, Washington entered civil service, representing Frederick County in the Virginia House of Burgesses from 1758 for seven years. While initially quiet, his political activism grew through the 1760s, establishing him as a prominent critic of Britain’s oppressive taxation and mercantilist policies. This wasn’t abstract theory; his personal finances, reliant on tobacco and imported goods, made him aware of vulnerabilities created by British rule.

Washington’s opposition crystallized around key legislative acts. He opposed the Stamp Act of 1765, celebrating its repeal. When the Townshend Acts followed, imposing duties on colonial imports, Washington championed economic resistance. In May 1769, he introduced a proposal urging Virginians to boycott British goods, demonstrating his belief in unified colonial action. This stance showcased his conviction that economic leverage was a potent weapon.

Beyond taxation, Washington was angered by other British interventions, notably the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which banned American settlement west of the Allegheny Mountains. As an active land speculator, this directly threatened his economic ambitions and colonial expansionist hopes. British interference in western land speculation thus merged personal interest with broader colonial grievances, solidifying his resolve to challenge the Crown. These early acts of political dissent revealed a fundamental belief in American colonists’ rights.

6. **The Road to Revolution: From Local Leader to Continental Delegate**The 1770s saw escalating tensions between colonies and Britain, with Washington at the storm’s epicenter. Parliament’s punitive Coercive Acts of 1774, responding to the Boston Tea Party, were viewed by Washington as an “invasion of our rights and privileges.” These acts, designed to punish Massachusetts, instead unified colonial grievances into a shared sense of threat. Washington understood an attack on one colony’s liberties was an attack on all.

In July 1774, Washington, with George Mason, drafted pivotal resolutions for the Fairfax County committee. These condemned British actions and included a radical call to end the Atlantic slave trade, demonstrating a nascent awareness of human rights alongside political liberty. The resolutions’ adoption underscored Washington’s growing influence and capacity to articulate a broader vision for self-governance. This period shows his evolution from local critic to a regional leader.

His commitment deepened when he attended the First Virginia Convention in August 1774, selected as a delegate to the First Continental Congress. As political temperatures rose, Washington took practical roles, helping train militias and organizing enforcement of the Continental Association boycott of British goods. These actions illustrate his seamless transition from orator to pragmatic organizer, embodying the revolutionary spirit and understanding the need for unity and military readiness.

7. **Commander-in-Chief: Taking the Reins of a Fledgling Army**War erupted on April 19, 1775, with the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Washington, with urgency, departed Mount Vernon on May 4 for the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia. There, on June 14, Congress created the Continental Army. The next day, John Adams, recognizing Washington’s military experience and unifying potential, nominated him as commander-in-chief, a unanimous election. This placed the enormous burden of military leadership on his shoulders.

Washington’s acceptance speech on June 16 set an immediate precedent for selfless service; he famously declined a salary, requesting only expense reimbursement. This gesture resonated deeply, affirming his commitment to the cause over personal gain, solidifying his image as a leader of integrity. He then assembled his primary staff, recognizing talent in figures like Henry Knox, chief of artillery, and Alexander Hamilton, his aide-de-camp. This team-building was crucial for the army’s foundational structure.

Initially, Washington banned Black individuals from joining the Continental Army. However, the British, exploiting divisions, offered freedom to slaves who joined their forces. This pragmatic move forced Washington to overturn his ban. By war’s end, roughly one-tenth of the Continental Army soldiers were Black, with some gaining freedom. This policy evolution underscored war’s pragmatic pressures. As he headed for Boston, he transformed into the living symbol of the Patriot cause, embodying a nation’s hopes for independence.

8. **The Perilous Philadelphia Campaign: Brandywine, Germantown, and Saratoga’s Shadow**As the nascent Continental Army gained confidence from its New Jersey triumphs, a new storm gathered on the horizon. In July 1777, General John Burgoyne’s British troops began their southward march from Quebec as part of the Saratoga campaign, aiming to sever New England from the other colonies. Meanwhile, General Howe, rather than reinforcing Burgoyne, made the fateful decision to move his substantial army from New York City south towards Philadelphia, the American capital. Washington and Gilbert, Marquis de Lafayette, swiftly rushed to engage Howe, recognizing the profound threat to the seat of the nascent government.

Yet, the defense of Philadelphia proved a harrowing chapter. In the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777, Howe masterfully outmaneuvered Washington, inflicting a significant defeat and allowing the British to march unopposed into the capital. It was a crushing blow, psychologically as much as strategically, leaving the Continental Congress scrambling to evacuate. The autumn brought further disappointment when a Patriot counter-attack against the British at Germantown in October also faltered, demonstrating the sheer challenge of dislodging a well-trained, professional army.

While Washington faced these setbacks in the middle states, General Horatio Gates achieved a monumental victory against Burgoyne in upstate New York. Reinforcements sent north by Washington, including Generals Benedict Arnold and Benjamin Lincoln, helped seal Burgoyne’s fate. On October 7, 1777, Burgoyne’s attempt to seize Bemis Heights failed, leading to his isolation and eventual surrender. Gates’ triumph, though vital for the Patriot cause, paradoxically emboldened Washington’s critics. As biographer John Alden noted, “It was inevitable that the defeats of Washington’s forces and the concurrent victory of the forces in upper New York should be compared,” and indeed, admiration for Washington began to wane in some quarters amidst these contrasting fortunes.

9. **Valley Forge: A Winter of Hardship and Transformation**As winter descended in December 1777, Washington and his beleaguered army of 11,000 men retreated to Valley Forge, a strategically chosen but brutally unforgiving encampment north of Philadelphia. It was a winter that would test the very soul of the Continental Army, where the enemy was not merely the British, but disease, starvation, and the gnawing cold. Between 2,000 and 3,000 men perished from sickness and exposure, dwindling the fighting force to fewer than 9,000 and casting a long shadow over the war effort.

By February, the situation had become dire, characterized by low troop morale and a surge in desertions. The hardship bred discontent, and Washington found himself fending off an internal revolt by his own officers, with some members of Congress even contemplating his removal from command. It was a profound crisis of leadership and confidence, yet Washington’s unwavering supporters held firm, and the movement to replace him ultimately collapsed, allowing him to retain control during this precarious period.

Facing this existential threat, Washington tirelessly petitioned Congress for vital provisions, conveying the desperate urgency of the army’s plight to a congressional delegation. His pleas resonated, leading to an agreement to bolster the army’s supply lines and to reorganize the quartermaster and commissary departments. Simultaneously, Washington initiated the “Grand Forage of 1778,” a concerted effort to collect essential food from the surrounding region, ensuring the survival of his troops through sheer, pragmatic will.

Crucially, it was during these frozen months that a pivotal figure emerged: Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben. This Prussian military officer, appointed Inspector General by Washington, implemented a rigorous and “incessant drilling” regimen. Under his stern but effective tutelage, Washington’s raw recruits were forged into a disciplined, professional fighting force, transforming Valley Forge from a scene of despair into a crucible of military excellence and resilience.

10. **French Alliance and the Battle of Monmouth: Turning the Tide**Just as hope seemed to flicker, early 1778 brought a momentous shift: the French entered into a Treaty of Alliance with the Americans, injecting vital resources and naval power into the war effort. This diplomatic triumph fundamentally altered the strategic landscape, transforming a colonial rebellion into a global conflict. The arrival of French support invigorated the Patriot cause and signaled to Britain that their fight for America would no longer be a contained affair.

In May, General Howe, perhaps weary of the stalemated war, resigned his command and was replaced by Sir Henry Clinton. Recognizing the new threat posed by the French fleet, Clinton decided to evacuate Philadelphia, the British-occupied American capital, in June, moving his forces back to the strategic stronghold of New York. This presented Washington with a tantalizing opportunity to strike a retreating, vulnerable enemy and reclaim the capital, a strategic and morale-boosting objective.

Washington swiftly summoned a war council comprising his American and French generals to debate the best course of action. Opting for a “limited strike” against the British as they withdrew, he dispatched Generals Lee and Lafayette with 4,000 men. However, the subsequent engagement on June 28 at Monmouth proved chaotic. Lee, acting without Washington’s explicit knowledge, bungled the initial strike, threatening to turn a potential victory into a rout. Washington, riding heroically onto the field, famously relieved Lee of command and personally rallied his troops, transforming the near-disaster into an expansive, hard-fought draw.

The Battle of Monmouth, though not a decisive victory, proved to be a critical turning point. It “marked the end of the war’s campaigning in the northern and middle states. Washington would not fight the British in a major engagement again for more than three years.” British attention definitively shifted to the Southern theater, with General Clinton capturing Savannah, Georgia, a key port, in late 1778. Meanwhile, Washington, ever strategic, ordered an expedition against the Iroquois, who were Indigenous allies of the British, systematically destroying their villages to curb their support for the Crown.

11. **The Shadow War: Washington’s Espionage Network and Arnold’s Treason**Beyond the conventional battlefields, Washington proved himself a master of clandestine warfare, effectively becoming America’s first spymaster. Recognizing the critical need for intelligence in asymmetric warfare, he designed an intricate espionage system to gather crucial information on British movements and intentions in New York. This shadowy network was a testament to his innovative leadership and his understanding that victory required more than just direct confrontation.

In 1778, acting under Washington’s direct instruction, Major Benjamin Tallmadge established the now-legendary Culper Ring. This covert group operated with remarkable effectiveness, collecting and relaying vital intelligence about British activities in New York. Indeed, intelligence gleaned from the Culper Ring proved instrumental, famously saving French forces from a surprise British attack, an attack that itself had been planned based on intelligence supplied by one of Washington’s own generals who had turned traitor.

This stunning betrayal was orchestrated by Benedict Arnold, a figure who had previously distinguished himself with valor in numerous campaigns, including the invasion of Quebec. Despite earlier “incidents of disloyalty,” Washington had consistently disregarded them, trusting in Arnold’s military prowess. Tragically, this trust was misplaced. In 1779, Arnold began secretly supplying the British spymaster John André with sensitive information, all with the insidious aim of allowing the British to capture West Point, a strategically vital American defensive position on the Hudson River.

On September 21, Arnold provided André with the detailed plans to take over the garrison. However, fate intervened when André was captured by militia, who discovered the incriminating plans. Arnold, alerted to André’s capture, narrowly escaped to New York. Upon learning of Arnold’s profound treason, Washington acted with characteristic decisiveness, immediately recalling commanders positioned under Arnold at key points around the fort to prevent any further complicity. He then assumed personal command at West Point, swiftly reorganizing its defenses and mitigating the damage from one of the most infamous betrayals in American history.

12. **Southern Strategy and the Triumph at Yorktown**By June 1780, the British had achieved firm control of the South, occupying the South Carolina Piedmont and securing key ports. The war in the North had largely stalled, and the prospect of overall victory seemed distant. However, Washington’s resolve was reinvigorated by the timely return of Lafayette from France, bringing with him more ships, men, and crucial supplies. This influx of support was soon amplified by the arrival of 5,000 veteran French troops led by Marshal Rochambeau at Newport, Rhode Island, in July, marking a significant escalation of allied power.

Meanwhile, General Clinton deployed Benedict Arnold, now a British brigadier general, to Virginia in December with 1,700 troops to capture Portsmouth and conduct devastating raids on Patriot forces. Washington, ever watchful, dispatched Lafayette south to counter Arnold’s disruptive efforts. Initially, Washington harbored hopes of launching a decisive strike against British forces in New York, believing this would draw the British away from Virginia and perhaps end the war in a single grand engagement. Yet, Rochambeau offered a different, more pragmatic counsel: Cornwallis’s forces in Virginia presented a more immediate and vulnerable target.

Embracing this strategic shift, on August 19, 1781, Washington and Rochambeau began their historic march to Yorktown, Virginia, a meticulously planned and executed maneuver now famously known as the “celebrated march.” Washington was at the helm of a formidable combined force of 7,800 Frenchmen, 3,100 militia, and 8,000 Continental troops. Despite his overall command, Washington, recognizing his inexperience in large-scale siege warfare, often deferred to the seasoned judgment of Rochambeau, a testament to his humility and strategic acumen. Crucially, Rochambeau never challenged Washington’s authority as the battle’s commanding officer, demonstrating the strength of their alliance.

By late September, the combined Patriot-French forces had successfully surrounded Yorktown, effectively trapping the entire British Army within the town’s defenses. Adding to this strategic encirclement, the French navy emerged victorious at the Battle of the Chesapeake, cutting off any possibility of British escape or reinforcement by sea. The final American offensive commenced with a symbolic shot fired by Washington himself, signaling the beginning of the end. The siege culminated in a British surrender on October 19, 1781, with over 7,000 British soldiers becoming prisoners of war.

Washington meticulously negotiated the terms of surrender over two intense days, ensuring a dignified but decisive conclusion. The official signing ceremony on October 19 sealed the fate of the British war effort. Although the formal peace treaty would not be negotiated for another two years, Yorktown undeniably proved to be the last significant battle of the Revolutionary War, compelling the British Parliament to agree to cease hostilities in March 1782, a victory born of strategic genius and allied cooperation.

Read more about: Unveiling America: A Deep Dive into the Nation’s Enduring Spirit, Milestones, and Unique Tapestry

13. **Demobilization and the Unprecedented Resignation**With the decisive victory at Yorktown, the long and arduous path to peace began. As formal negotiations commenced in April 1782, both the British and French forces gradually initiated their respective evacuations from American soil. However, the end of the war brought its own set of challenges, not least among them the simmering discontent within the ranks of the American officers, dissatisfied with the lack of pay and uncertain futures.

In March 1783, this frustration boiled over into the Newburgh Conspiracy, a planned mutiny by American officers that threatened to unravel the fragile republic before it had truly begun. In a masterful display of leadership and persuasive rhetoric, Washington successfully calmed the agitated officers, appealing to their patriotism and reminding them of the sacrifices they had made for a higher cause. His intervention was a critical moment, averting a potentially catastrophic internal conflict.

Following this crisis, Washington submitted a meticulous account of $450,000 in expenses that he had personally advanced to the army throughout the war. While the account was settled, it included entries that were notably vague about large sums and even encompassed expenses his wife had incurred through her visits to his headquarters, painting a picture of a leader deeply entwined with the war effort, both personally and financially.

Finally, with the signing of the Treaty of Paris on September 3, 1783, Britain officially recognized American independence, bringing the war to its official close. Washington, with characteristic solemnity, disbanded his army, delivering a heartfelt farewell address to his soldiers on November 2. He then personally oversaw the evacuation of British forces from New York City and was met with widespread parades and celebrations, a hero’s welcome for the man who had delivered liberty.

In early December 1783, Washington gathered his officers for an emotional farewell at Fraunces Tavern before making his final, transformative appearance in uniform. He resigned his commission as commander-in-chief to the Congress, declaring, “I consider it an indispensable duty to close this last solemn act of my official life, by commending the interests of our dearest country to the protection of Almighty God, and those who have the superintendence of them, to His holy keeping.” This unprecedented act of a victorious general voluntarily relinquishing power was acclaimed both at home and abroad, as historian Edward J. Larson noted, “extolled by later historians as a signal event that set the country’s political course.” That same month, Washington was appointed president-general of the Society of the Cincinnati, a newly established hereditary fraternity of Revolutionary War officers.

14. **Laying the Foundations: Return to Mount Vernon and the Constitutional Convention**After a grueling 8.5 years of war, during which he spent a mere ten days at Mount Vernon, Washington was profoundly eager to return to the tranquility of his beloved estate. Arriving on Christmas Eve, he found immense satisfaction in being “free of the bustle of a camp and the busy scenes of public life,” as Professor John E. Ferling observed. Yet, his private life was far from solitary, as he received a constant stream of visitors, a testament to his enduring status as a national hero and elder statesman.

Upon his return, Washington reactivated his pre-war interests in the Great Dismal Swamp and Potomac Canal projects, though neither ultimately yielded significant dividends. He also undertook an extensive 34-day, 680-mile trip in 1784 to inspect his land holdings in the Ohio Country. At Mount Vernon, he meticulously oversaw remodeling work that transformed his residence into the iconic mansion we know today. However, his financial situation remained precarious; creditors often paid him in depreciated wartime currency, and he grappled with significant debts in taxes and wages. His estate had yielded no profit during his long absence, suffering from persistently poor crop yields due to pestilence and adverse weather, recording its eleventh consecutive year at a deficit by 1787.

To restore Mount Vernon’s profitability, Washington embarked on an ambitious new landscaping plan and successfully cultivated a diverse range of fast-growing trees and native shrubs. Demonstrating his innovative spirit, he also began breeding mules after receiving a stud from King Charles III of Spain in 1785, firmly believing that these hardy animals would “revolutionize agriculture” in America. These efforts highlighted his pragmatic approach to husbandry and his vision for agricultural advancement.

Even in his desired retirement, Washington’s sense of duty to the young republic remained paramount. Before returning to private life in June 1783, he had already called for a strong union, recognizing the inherent weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation. He expressed concern about meddling in civil matters but nonetheless sent a circular letter to the states, poignantly describing the Articles as no more than “a rope of sand.” He foresaw a nation on the brink of “anarchy and confusion” and vulnerable to foreign intervention, convinced that only a robust national constitution could unify the disparate states under a strong, central government.

The widespread unrest epitomized by Shays’s Rebellion in Massachusetts in August 1786 only further solidified Washington’s conviction that a national constitution was desperately needed. Nationalists, fearing the republic’s descent into lawlessness, convened in Annapolis in September 1786 to advocate for revisions to the Articles. Congress, persuaded, called for a Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Washington, initially reluctant due to concerns about the convention’s legality, was eventually persuaded by figures like James Madison and Henry Knox that his presence was indispensable—it would induce hesitant states to send delegates, smooth the ratification process, and lend unparalleled legitimacy to the entire endeavor.

Washington arrived in Philadelphia on May 9, 1787, and when the convention formally began on May 25, Benjamin Franklin himself nominated him to preside. He was unanimously elected, a testament to the immense respect he commanded. During the convention, Edmund Randolph introduced Madison’s Virginia Plan, advocating for an entirely new constitution and a sovereign national government—a concept Washington ardently supported. However, contentious details surrounding representation, particularly between larger and smaller states, led to a competing New Jersey Plan. On July 10, a weary Washington confided to Alexander Hamilton, “I almost despair of seeing a favorable issue to the proceedings of our convention and do therefore repent having had any agency in the business.” Despite moments of profound frustration, his unparalleled prestige and consistent lobbying efforts among the delegates proved crucial, ultimately leading to the adoption of the Connecticut Compromise between the two plans. On September 17, the finished Constitution was signed by 39 of the 55 delegates, a document forever marked by Washington’s silent but powerful influence, solidifying his role not just as the Father of the Nation, but also as the architect of its enduring framework.