Alright, buckle up, literary explorers! We’re about to dive deep into a novel that shook the world, won a Pulitzer Prize, and continues to reverberate through culture and academia: Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved.’ This isn’t just a book; it’s an experience, a raw and unflinching look at the unbearable legacies of slavery, rendered with a poetic intensity that only Morrison could command. If you’ve ever felt the pull of a story that lingers long after you’ve turned the final page, then you know the power we’re talking about here.

Published in 1987, ‘Beloved’ quickly cemented its place as a modern classic, a testament to Morrison’s unparalleled ability to weave historical truth with deeply personal, often painful, human experiences. The novel doesn’t just tell a story; it compels us to confront difficult truths, to understand the unseen wounds that slavery inflicted, and to witness the extraordinary resilience of those who survived it. It’s a journey into memory, trauma, and the fierce, sometimes destructive, power of love.

So, grab your thinking caps, because we’re unpacking ‘Beloved’ one powerful insight at a time. From its real-life origins to its groundbreaking themes and unforgettable characters, we’re covering everything you need to know about why this book remains so incredibly vital. Let’s get into it!

1. The Real-Life Inspiration: Margaret Garner’s Story

Before there was Sethe, there was Margaret Garner. Toni Morrison’s main inspiration for ‘Beloved’ was a chilling account titled ‘A Visit to the Slave Mother who Killed Her Child,’ an 1856 newspaper article initially published in the American Baptist and later reproduced in ‘The Black Book,’ an anthology of Black history and culture that Morrison herself edited in 1974. This historical incident provided the agonizing core of the novel.

Garner was an enslaved woman in Kentucky who, in 1856, escaped to the free state of Ohio. However, under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, she was subject to capture. When U.S. marshals broke into the cabin where she and her children had barricaded themselves, Garner was attempting to kill her children, and had already killed her youngest daughter, in a desperate bid to spare them from the horrific fate of being returned to slavery. This unfathomable act, driven by a mother’s fierce, protective love and extreme terror, is the historical bedrock upon which Sethe’s story is built, immediately setting a tone of profound tragedy and moral complexity.

Morrison took this historical fragment and expanded it into a narrative that explores not just the act itself, but its psychological aftermath and the broader implications of slavery on the human spirit. The decision to kill one’s own child to prevent re-enslavement is perhaps one of the most agonizing choices a human could ever face, and it forces readers to grapple with the true depths of cruelty and desperation that the institution of slavery created. It challenges our understanding of good and evil, protection and destruction.

This real-life story highlights the pervasive and brutal reality of slavery, where even a mother’s sacred bond with her children could be twisted into a horrific act of mercy. It underscores the novel’s relentless pursuit of truth, ensuring that the reader understands the unbearable weight of living under such an oppressive system. It’s a stark reminder that the unimaginable was, for many, a grim reality.

2. The Novel’s Haunting Setting and Initial Conflict

‘Beloved’ begins in 1873 in Cincinnati, Ohio, introducing us to Sethe, a formerly enslaved woman, and her 18-year-old daughter, Denver, living at 124 Bluestone Road. This house isn’t just a home; it’s a character in itself, haunted for years by what Sethe and Denver believe is the ghost of Sethe’s eldest daughter. The very address, “124,” becomes a shorthand for the isolation and spectral presence that define their existence.

Denver, a shy, friendless, and housebound young woman, has formed a strange companionship with this invisible entity. The ghost’s malevolent spirit has driven Sethe’s sons, Howard and Buglar, away by the age of 13, leaving Sethe and Denver in a state of quiet, haunted despair. Baby Suggs, Sethe’s mother-in-law and Halle’s mother, had died eight years prior, further isolating the remaining family members in their grief and spectral company.

Then, a turning point arrives in the form of Paul D, one of the enslaved men from Sweet Home, the plantation where Sethe, Halle, Baby Suggs, and others were once held captive. His arrival is a disruption, forcing out the spirit that had become Denver’s only companion and sparking her contempt. Paul D’s presence, however, is also a catalyst for change, persuading Sethe and Denver to leave the house for the first time in years to attend a carnival, a brief taste of normalcy and joy.

This initial setup masterfully establishes the novel’s core conflicts: the lingering trauma of slavery, the isolation it engenders, and the desperate yearning for connection and healing. The haunted house is a metaphor for the characters’ own internal landscapes, brimming with unresolved pain and spectral memories. Paul D’s entrance signals a potential for new life, but also a disturbance of the delicate, albeit painful, equilibrium Sethe and Denver have maintained.

Read more about: The Echoes of Giants: How Enduring Literature Navigates a Fragmented World and a Shifting Cultural Landscape

3. The Enigmatic Arrival of Beloved

Returning home from their rare outing to the carnival, Sethe, Paul D, and Denver discover a young woman sitting on their doorstep. She introduces herself simply as Beloved. This mysterious figure is soaking wet and sickly, sparking immediate suspicion in Paul D, who wisely warns Sethe. However, Sethe is captivated, charmed by the young woman, and chooses to ignore Paul D’s apprehension, inviting Beloved into their home.

Denver, lonely and starved for companionship, is eager to care for the ailing Beloved. She quickly begins to believe that this mysterious woman is, in fact, her older sister, returned from the grave. This belief immediately shifts the dynamic within 124 Bluestone Road, creating a new, complex set of relationships and opening old wounds. Beloved’s presence feels both miraculous and unsettling, a physical manifestation of the past refusing to stay buried.

Paul D, meanwhile, finds himself increasingly uncomfortable in the house, feeling as though he is being deliberately driven out. This discomfort culminates one night when Beloved corners him, making a ually explicit demand that fills his mind with horrific memories from his past, including the sexual violence he endured in a chain gang. This disturbing encounter shatters his peace and further isolates him from Sethe, who he struggles to confide in.

Unable to articulate the full horror of his experience with Beloved, Paul D instead tells Sethe he wants her pregnant, a desire that stems from a deep-seated need to start anew, free from the ghosts of the past. But Sethe, afraid to live for another baby after her previous trauma, is resistant. When Stamp Paid reveals a newspaper clipping about Sethe’s act of infanticide, Paul D confronts her, leading to Sethe’s stark admission of her desperate act to “put my babies where they would be safe.” Paul D, unable to reconcile this “thick” love with his own understanding, leaves 124, setting the stage for Sethe’s deepening immersion into the mystery of Beloved.

Read more about: The Single Business Investment That Made Jessica Alba a Billionaire

4. Mother-Daughter Bonds and Their Devastating Consequences

At the heart of ‘Beloved’ lies an intense exploration of maternal bonds, particularly those between Sethe and her children, and how these relationships are profoundly warped by the brutality of slavery. Morrison depicts Sethe as developing a “dangerous maternal passion” – a love so fierce and protective that, in the face of re-enslavement, it leads her to kill her own daughter. This tragic act, intended to salvage her “fantasy of the future,” her children, from a life in slavery, becomes a haunting presence that shapes her entire existence.

Sethe’s actions have devastating consequences, not only for the child she loses but also for her surviving daughter, Denver. Isolated from the Black community due to the horror of her mother’s act, Denver is denied the crucial social interaction needed to enter into womanhood. It is only with the arrival of Beloved, and the subsequent need to seek help, that Denver begins to establish her own self and embark on her individuation. Her journey mirrors Sethe’s eventual path to self-acceptance.

Morrison also delves into the intergenerational trauma of stolen motherhood. Baby Suggs, Sethe’s mother-in-law, coped with the repeated loss of her children by refusing to become too close to them, remembering what she could but protecting herself from deeper attachment. Sethe, in stark contrast, tried to hold onto her children, to fight for them, even to the point of killing them for their freedom. This fundamental difference highlights the varying coping mechanisms born from similar pain, both tragic in their own ways.

Furthermore, Sethe’s trauma is deeply physical and symbolic. Having had her milk stolen by Schoolteacher’s nephews, she was unable to form the symbolic bond between herself and her daughter by feeding her. This act of violation denied her a fundamental maternal experience, leaving a lasting scar that underscores the dehumanizing nature of slavery and its profound impact on even the most basic human connections. Her desperate acts are, in part, a reaction to this primal violation.

Read more about: Unveiling the Layers of Legacy: 11 Jaw-Dropping Insights into Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’ That Still Resonate

5. The Deep Scars: Psychological Effects of Slavery

‘Beloved’ serves as a profound examination of the psychological effects of slavery, illustrating how the suffering endured under this brutal institution led many former slaves to repress their traumatic memories in a desperate attempt to forget the past. This repression and dissociation from earlier identities caused a fragmentation of the self, a loss of true identity that haunted individuals long after emancipation. The past, it seems, is never truly past.

Characters like Sethe, Paul D, and Denver all bear the scars of this loss of self. Their healing journey is contingent upon their ability to reconcile with their pasts and integrate these painful memories into a coherent sense of identity. Beloved, the enigmatic figure, serves as a powerful, albeit disruptive, catalyst in this process, forcing these characters to confront their repressed memories and ultimately leading to the painful but necessary reintegration of their fragmented selves. She is the embodiment of the unaddressed past.

Slavery, as depicted by Morrison, splits a person into a “fragmented figure.” The identity, composed of painful memories and unspeakable experiences, is denied and kept at bay, creating a “self that is no self.” To heal and humanize, one must find a language to constitute this identity, to reorganize the painful events, and to retell these memories. The novel suggests that the “self” is located in a word, defined by others, and that power lies in the audience—or more precisely, in the word itself. Once the word changes, so too can identity.

All the characters in ‘Beloved’ face the formidable challenge of remaking a self composed of their “rememories” and defined by external perceptions and language. The primary barrier to this remaking is often their desire for an “uncomplicated past” and the paralyzing fear that remembering will lead them to “a place they couldn’t get back from.” This internal struggle against the haunting past is a central psychological tension that Morrison masterfully explores, showing how deeply ingrained trauma requires immense courage to confront and integrate.

Read more about: Unveiling the Layers of Legacy: 11 Jaw-Dropping Insights into Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’ That Still Resonate

6. Defining Manhood in a Post-Slavery World

Morrison’s ‘Beloved’ delves into the complex and often distorted definition of manhood and masculinity in the aftermath of slavery, revealing how the institution stripped men of their very sense of self. The novel doesn’t just depict emotions like love and self-preservation; it accurately portrays the horrors of enslavement and their profound effects on men, communicating new morals and understandings of what manhood could mean in a society that denied it to Black men.

Through stylistic devices, Morrison provides insight into Paul D’s perception of manhood. His half-formed words and thoughts give the audience a glimpse into his internal struggles, constantly challenged by the norms and values of white culture. His dreams and goals, once high, are rendered unreachable by racism, leaving him feeling that despite his sacrifices, society will never “pay him back” or allow him to achieve what his heart desired. This constant dissonance between aspiration and reality is a crushing blow to his masculinity.

Scholar Zakiyyah Iman Jackson notes that Paul D’s reduced manhood emerges in relation to a “discourse of animality,” highlighting how racist ideologies dehumanized Black men, reducing them to chattel. This is vividly symbolized by Paul D’s “tobacco tin” for a heart, a metaphor for how he contained his painful memories, shutting off his emotions to survive. It speaks volumes about the emotional repression forced upon him to maintain a semblance of self in an oppressive world. Beloved’s arrival, ironically, is what forces this tin to open.

The Reconstruction era (1890–1910) brought with it Jim Crow laws, further limiting the movement and involvement of African Americans in white-dominant society. Black men like Paul D struggled immensely to establish their own identity and achieve their goals due to these “disabilities” that constrained them to a lower social hierarchy. Stamp Paid’s observation of Paul D—”liquor bottle in hand, stripped of the very maleness that enables him to caress and love the wounded Sethe”—perfectly encapsulates this struggle, portraying him as a foundational, yet exploited, pillar of society, denied the very essence of his manhood.

Alright, lit squad, let’s keep this journey through ‘Beloved’ going strong! We’ve already peeled back some serious layers, from its real-life origins to the crushing psychological toll of slavery. Now, prepare yourselves, because we’re diving even deeper into the heart of this masterpiece, uncovering how family ties were twisted, how pain became a constant companion, and how heroism emerged in the most unexpected ways. Plus, we’ll check out its life beyond the page and its lasting impact on, well, pretty much everything. Let’s roll!

Read more about: Unearthing Trauma: The Enduring Narrative of ‘Beloved’ for a Dark and Gritty Live-Action Reboot

7. Fractured Family Relationships: The Invisible Chains

If you thought slavery only broke bodies, ‘Beloved’ is here to remind you that it absolutely shattered family structures too. The novel lays bare how the institution denied African Americans basic rights to their own bodies, their children, and their families. Sethe’s horrific act of infanticide, for example, is portrayed not as simple murder, but as a desperate, misguided attempt to preserve her daughter from a fate she believed to be worse than death—a truly peaceful act in her eyes, born from an unimaginable bind. It’s a stark, heartbreaking depiction of the choices forced upon enslaved people.

This isn’t just about the immediate tragedy, though. The novel shows how these families, even after the Emancipation Proclamation, remained profoundly broken and bruised by the hardships they’d endured. Unable to fully participate in broader society, formerly enslaved people often leaned into the supernatural, performing rituals and praying to their gods for solace and understanding. This spiritual reliance becomes a crucial coping mechanism in a world that offered little else.

Beloved herself, the spectral figure haunting 124 Bluestone Road, is a vivid manifestation of these fractured family relationships and the deep mental strife Sethe carries. Sethe truly believes this young woman is the daughter she murdered 18 years prior, a testament to how grief, guilt, and trauma can twist perception. Her return forces the family to confront the unaddressed wounds of the past, creating a dynamic that is both agonizingly real and profoundly symbolic.

8. The Pervasive Nature of Pain: Echoes That Linger

‘Beloved’ isn’t shy about showcasing pain, and honestly, it makes you realize just how universal it was for everyone caught in the web of slavery. Whether physical, mental, sociological, or psychological, the scars ran deep. What’s truly wild is how some characters, in a twisted survival mechanism, tend to ‘romanticize’ their pain, viewing each harrowing experience as a turning point, a strange form of beautification that echoes in both early Christian contemplative and African-American blues traditions.

Morrison masterfully crafts a narrative that feels like a complex labyrinth, because all the characters have been ‘stripped away’ from their voices, their narratives, their very language. This diminishment of self means each character’s experience with slavery is distinct, yet all are united by this profound sense of loss. It’s like trying to piece together a mosaic with shards that don’t quite fit, each one holding a different piece of unimaginable suffering.

Take Sethe, for instance, with her infamous ‘choke-cherry tree’ scars. She keeps repeating what a White girl said about them, trying to find beauty in the horror, as if naming it something lovely could erase the agony. But Paul D and Baby Suggs, having seen the true brutality, look away in disgust, refusing to romanticize such deep wounds. It highlights the profound struggle to process and articulate unspeakable suffering.

And then there’s Beloved, the very embodiment of memory, grief, and spite. Her presence in the house, a place meant for vulnerability and heart, is fiercely debated. Paul D and Baby Suggs intuit her malevolent nature, wanting her out. But Sethe, blinded by her desperate longing for her lost child, sees only her daughter, alive and grown, rather than the raw pain of her murder. Ultimately, it’s Paul D who, in a beautiful moment, encourages Sethe to move past this consuming pain, urging her to find love for herself instead of clinging to the ghost of what was. Talk about a powerful mic drop moment!

9. Unconventional Acts of Heroism: Defying the ‘Norm’

When you hear ‘heroism,’ you probably picture capes and superpowers, right? Well, ‘Beloved’ challenges that notion, suggesting heroism isn’t just about grand gestures, but about having the guts to do what you believe is right, even when the world is screaming at you to stop. It’s not absolute; it’s shaped by experience and community, and Sethe, our protagonist, is the ultimate unconventional hero.

Sethe’s agonizing decision to kill her own child, Beloved, is perhaps the most controversial ‘heroic’ act in the book. The community condemns her, but Sethe never wavers in her conviction. She wasn’t trying to understand what was ‘worse’; she was trying to prevent ‘what [she] know[s] is terrible.’ For her, death was a far more merciful option than a life back in the hellish confines of slavery. It’s a definition of heroism born from extreme love and desperation, defying every societal expectation.

Her heroism isn’t just about that singular, devastating act. Sethe also helps Paul D confront his own brutal past, allowing him to reclaim a piece of his shattered masculinity. She never mentions or looks at the ‘neck jewelry’ – the scars from the iron bit – that forever altered him. This silent acknowledgment, or rather, lack thereof, allows Paul D to retain his manhood, a profound act of tenderness and understanding that showcases Sethe’s capacity to heal others, even as she grapples with her own wounds. He wants his story next to hers, a testament to her unique power.

But wait, there’s another hero in the house! Denver, initially isolated and timid, eventually defies the confinements of her own past. She realizes that both Sethe and Beloved are spiraling, caught in a parasitic grip, and it’s up to her to ‘step off the edge of the world’ and seek help from the community she’d been estranged from. This courageous step, literally leaving the only world she knows, not only secures her own independence but also sparks a collective act of heroism that ultimately frees her mother from Beloved’s destructive influence. It’s a powerful reminder that sometimes, the greatest heroism is simply asking for help and daring to build a future.

10. Pivotal Characters: Sethe, Beloved, and Denver’s Journeys

At the heart of ‘Beloved’ are a trio of unforgettable women whose intertwined fates drive the novel’s powerful narrative. Sethe, the protagonist, is a force of nature—resilient, yet deeply defined by the trauma of slavery and the ‘tree on her back’ from whipping. She’s fiercely maternal, willing to do anything to protect her children, even if it means committing the unimaginable. Her character is a living testament to the enduring scars of the past.

Then there’s Beloved, the enigmatic figure who appears soaking wet on Sethe’s doorstep, widely believed to be the ghost of the murdered baby. Morrison herself confirmed this interpretation, making Beloved the physical manifestation of unaddressed grief, guilt, and the collective trauma of slavery. She acts as a catalyst, forcing the family to confront repressed memories, yet her presence also becomes consuming and destructive, slowly draining Sethe’s life force.

Finally, we have Denver, Sethe’s surviving daughter, who undergoes a remarkable transformation. Initially shy, friendless, and housebound, forming a strange companionship with the haunting spirit, Denver evolves into a protective and independent woman. Her journey from isolation to actively seeking help from the Black community marks her individuation, breaking the cycle of despair at 124 Bluestone Road and fighting not only for her own future but also for her mother’s wellbeing. These three women, in their complex dance of love, pain, and resilience, create an unforgettable portrait of survival.

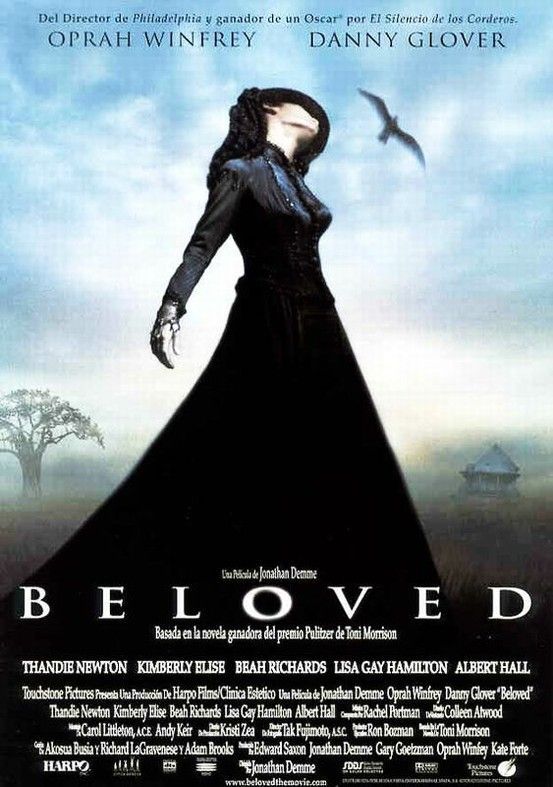

11. From Page to Screen and Sound: Adaptations of ‘Beloved’

When a book hits you as hard as ‘Beloved,’ it’s almost inevitable that its powerful story will jump off the page and into other mediums. The fact that Morrison’s narrative has been adapted is a testament to its universal themes and enduring impact, reaching audiences far beyond the literary world. It’s like, can you imagine all that emotional weight translated onto a screen or through your headphones? Pure magic (and trauma, let’s be real).

In 1998, the novel made its cinematic debut with a film adaptation directed by Jonathan Demme, and impressively, produced by and starring none other than Oprah Winfrey. Bringing a story this profound to the big screen is a massive undertaking, and Winfrey’s involvement ensured a wide audience was introduced to Sethe’s harrowing journey, further cementing the novel’s place in popular culture.

But the adaptations didn’t stop there! In January 2016, ‘Beloved’ found a new voice on BBC Radio 4, broadcast in 10 episodes as part of its ’15 Minute Drama’ program. Adapted by Patricia Cumper, this radio series proved that the novel’s gripping narrative and rich character development could captivate listeners even without visual cues, showcasing its versatility and the timelessness of its storytelling across different artistic forms. Pretty cool, right?

Read more about: The Enduring Story of Michelle: Tracing a Name’s Global Journey and Cultural Impact

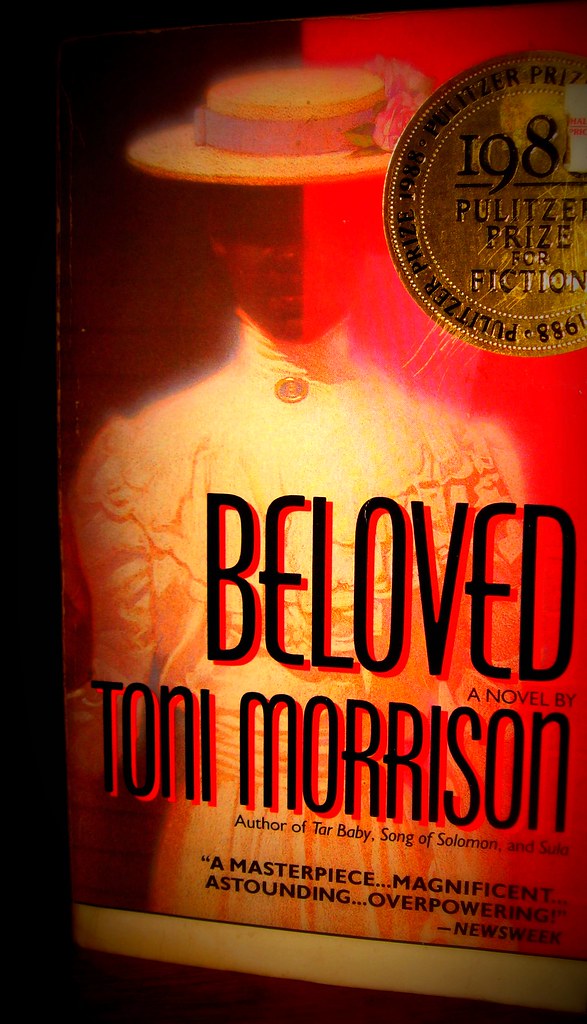

12. ‘Beloved”s Enduring Legacy and Impact: A Story That Won’t Quit

Talk about making a splash! ‘Beloved’ absolutely crushed it in terms of critical reception, earning Toni Morrison the greatest acclaim of her career. It snagged the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, the Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Book Award, the Melcher Book Award, and more. And get this: when it was nominated but didn’t win the National Book Award, 48 prominent African-American writers and critics actually signed a protest letter published in The New York Times Book Review! That’s how passionate people were (and still are!) about this book.

More than just awards, ‘Beloved’ has become a cornerstone for exploring fundamental concepts like family, trauma, and the complex ways memory works. It’s seen as a powerful act of restoring the historical record, giving voice to the collective memory of African Americans, especially through its controversial dedication, ‘Sixty Million and more,’ referring to the victims of the Atlantic slave trade. Morrison herself stated the book had to exist because there was ‘no suitable memorial or plaque or wreath or wall or park or skyscraper lobby’ to honor these lives. Talk about a mission statement!

This powerful sentiment even led to the ‘bench by the road’ project, where the Toni Morrison Society started installing benches at significant sites in slavery’s history across America. The first was dedicated on Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina, a poignant entry point for so many enslaved Africans. It’s a beautiful, tangible way to remember and honor those who suffered, literally providing a place to sit and reflect on the past, inspired by Morrison’s own words.

And even after all these years, ‘Beloved’ continues to spark conversation and, yes, even controversy. Scholars still debate the true nature of the character Beloved – is she a literal ghost or a real person? This ambiguity only deepens the novel’s exploration of familial ties and the weight of the past. But for all its critical acclaim and profound themes, ‘Beloved’ has also faced its share of censorship and banning in U.S. schools due to its graphic content involving and violence. This ongoing debate, decades after its publication, just proves how incredibly potent and relevant this story remains, forcing us to confront uncomfortable truths and ensuring its legacy as a truly unforgettable, essential piece of American literature. It’s a book that demands to be read, discussed, and remembered, pushing us all to answer those lingering questions about our past and what it means for our present.