The 1870s represent a truly pivotal moment in American history, a decade where the echoes of the Civil War were still settling, yet the drumbeat of a new era was growing unmistakably louder. This was a time of intense transformation, as the nation grappled with its past while rapidly forging a future that would lay the groundwork for the modern United States. Through a remarkable collection of photographs and accompanying historical insights, we are invited to embark on a journey, peeling back the layers of 150 years to witness the very essence of life during what is often called the Gilded Age.

These curated snapshots offer far more than simple nostalgia; they are vivid windows into the streets, farms, factories, and homes of a society undergoing profound change. From the incessant hum of the telegraph to the majestic roar of steam locomotives, America was redefining itself, connecting distant corners, and embracing innovations that would forever alter its social and economic landscape. It was an era marked by rapid industrial growth, the complex tail-end of Reconstruction, and the initial great wave of immigrant arrivals, all contributing to a vibrant, often challenging, yet undeniably formative period.

Join us as we explore a selection of these compelling images and the rich stories they tell. Each photograph acts as a portal, not just showcasing a visual record but also offering profound context that brings the scenes to life, allowing us to understand the complex tapestry of daily existence, monumental shifts, and the enduring legacies of America’s past. We will delve into the bustling urban centers, the vast rural landscapes, the technological leaps, and the intricate social dynamics that shaped the lives of ordinary Americans a century and a half ago.

1. The Urban Transformation: Bustling Cities and Rapid Growth

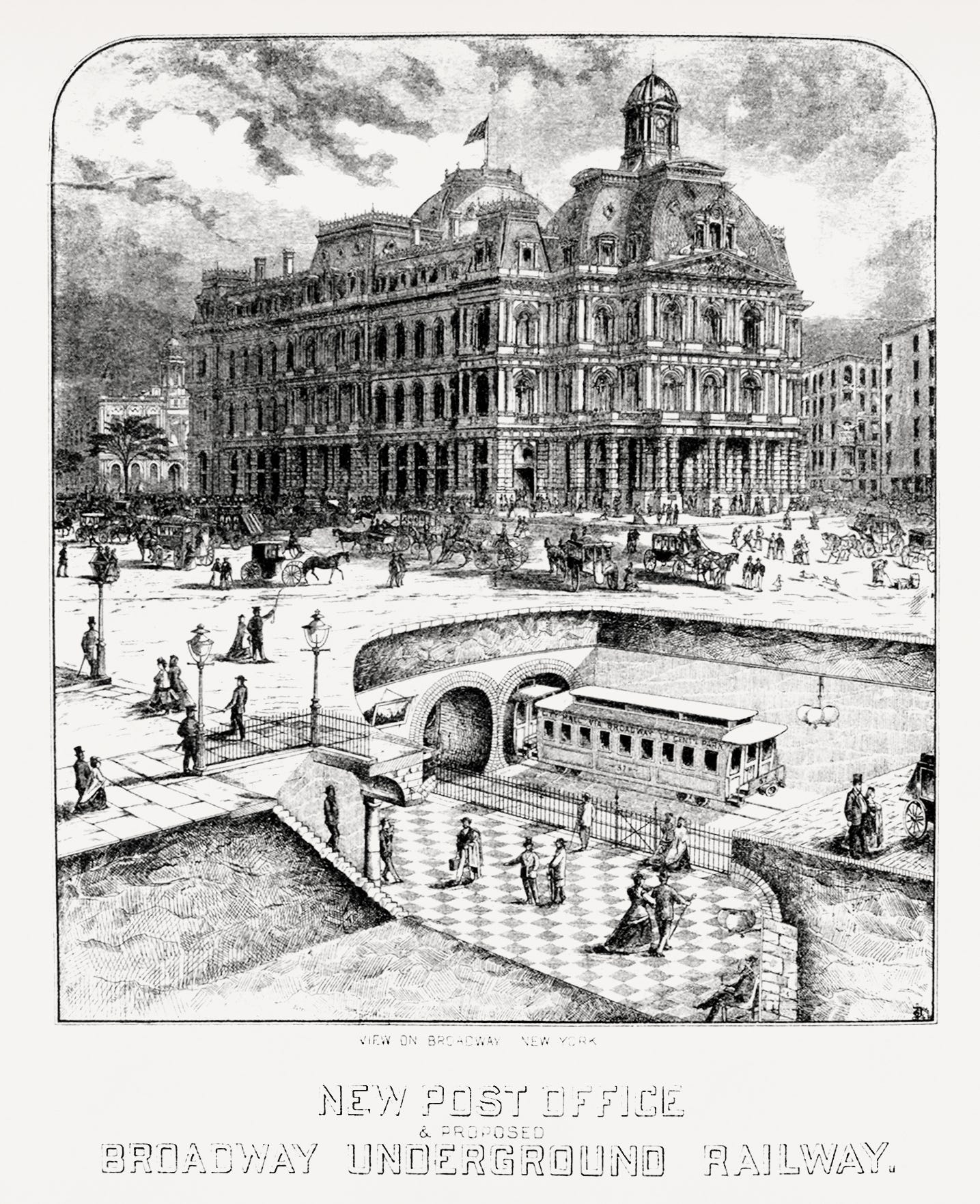

The opening scenes of America’s urban landscape 150 years ago reveal a dynamic contrast to the quiet rural expanses. Imagine New York City’s Fifth Avenue in 1872, a vibrant artery where “horse-drawn carriages clattered past storefronts still brimming with hand-crafted wares.” This image captures the palpable energy of a city on the rise, a testament to the ongoing shift as people gravitated towards the promise of urban life, moving away from agricultural pursuits to seek opportunities in burgeoning industries.

Further west, Chicago presented an even more dramatic spectacle of rebirth and relentless progress. Just two decades after the devastating Great Fire of 1871, an image of the Chicago Loop captures a “skyline of brick and steel in the throes of the city’s rebirth.” This powerful visual is a testament to human resilience and ambition, demonstrating how “the scars of the fire became the raw material for the city’s modern infrastructure.” It illustrates a city not merely recovering, but actively transforming itself into a major commercial hub, driven by new building codes and the establishment of modern fire-rescue teams.

This rapid urbanization was a defining characteristic of the Second Industrial Revolution, which was “in full swing, driving rapid changes in culture, technology, and the economy.” Cities like New York and Chicago “boomed as factories drew people from rural areas,” fundamentally altering the demographic balance of the nation. However, this growth also brought significant challenges, leading to “overcrowded conditions and the rise of tenement housing,” where “entire families” were often packed “into one-room apartments,” frequently enduring “squalor and unsafe environments.”

The streets themselves were a theater of daily life, offering glimpses into the social strata of the time. We see “men in frock coats and women in stiff-bodied gowns,” representing “the everyday look of the middle-class elite.” These detailed observations not only provide a visual record of fashion but also hint at the emerging class distinctions within these rapidly expanding urban centers, where wealth accumulation was reshaping American society and leading to significant disparities.

Read more about: Unveiling America: A Deep Dive into the Nation’s Enduring Spirit, Milestones, and Unique Tapestry

2. The American Heartland: Life on Farms and Homesteads

Away from the clamor of the cities, a different, yet equally foundational, story was unfolding across the American heartland. A striking series of images transports us to the vast “wheat fields of Iowa in 1875,” where “men in broad-brimmed hats tend to the furrows, while children run barefoot beside the cornrows.” These scenes paint a vivid picture of the agrarian lifestyle that still dominated much of the nation, a stark contrast to the industrializing urban centers, yet equally crucial to America’s identity and economy.

Another poignant image, an “Iowa homestead,” illustrates the simplicity and self-sufficiency of rural existence. It showcases a “modest clapboard house, with a barn and a well that still uses a hand-pulled bucket,” serving as a powerful visual reminder of the daily realities and sheer physical labor involved in sustaining life on the frontier. These images are deeply intertwined with the legacy of the 1862 Homestead Act, described as a “policy that turned farmland into a promise of opportunity for millions of settlers.” This landmark legislation fueled a massive westward push, fundamentally “reshaping the American demographic landscape.”

However, the promise of opportunity often came hand-in-hand with immense hardship. While many moved “out west to settle and farm the open land,” hoping for a better life, the reality for these pioneers was often arduous. Their lifestyles were frequently characterized by “long, hard hours of labor, poor living conditions, and economic hardship,” directly challenging any romanticized notions of the frontier. These settlers, far from the stereotypical “cowboys,” were resilient individuals striving to carve out a living against formidable odds.

The continuous expansion into the West, driven by the Homestead Act and facilitated by the burgeoning railroad network, highlights a nation constantly expanding its physical borders. It underscores the profound aspiration for land and independence that defined a significant portion of the American populace, even as industrialization began to pull others towards the cities. This dual movement, both urban and rural expansion, speaks volumes about the diverse motivations and dreams shaping the nation 150 years ago.

3. The Iron Horse: Revolutionizing Transportation and Connection

No single innovation better symbolizes America’s relentless drive for connection and expansion in the 1870s than the railroad. Imagery of the “Iron Horse” dominates this period, illustrating the sheer scale of the nation’s ambition. The “first transcontinental railroad,” completed in 1869, had already begun to weave a new tapestry across the continent, an engineering marvel that drastically shrunk distances and accelerated the pace of national development.

A powerful 1873 photograph shows “workers in a Texas rail yard, hauling rails across a vast plain,” a testament to the immense human effort involved in expanding this intricate network. Simultaneously, a bustling 1870 image from the U.S. National Archives captures a vibrant “depot in Kansas City, complete with a steam locomotive chugging past,” showcasing the central role these hubs played in the daily movement of goods and people. These scenes bring to life the transformative power of this new mode of transport.

The impact of the railroads extended far beyond mere transit; they were catalysts for profound socio-economic change. The context underscores how railroads “did more than just transport goods—they connected cities, lowered shipping costs, and even helped fuel the gold rushes in the West.” Before 1871, “45,000 miles of railroad track had already been laid,” but the subsequent decades saw an astonishing acceleration, with another “170,000 miles” added by 1900. This rapid expansion meant that “train travel became popular” and accessible to more segments of society.

Furthermore, the railway system revolutionized daily life by fundamentally altering food distribution. Suddenly, “people were gaining access to foods that weren’t easily accessible in their geographical areas before.” The East Coast could now “suddenly consume oranges from California, beef from Wyoming, and fresh milk,” leading to a significant “expansion in the American diet beyond the previous regional bounds.” This period also saw the emergence of “luxury train travel,” with the launch of high-end cars like those from the Pullman Palace Car Company in 1875, catering to the “wealthiest passengers” and symbolizing the growing wealth disparity of the Gilded Age.

4. Technological Marvels: Telegraphy and Early Photography

Beyond the physical connections forged by railroads, the 1870s also witnessed a revolution in how Americans communicated and captured their world, laying the groundwork for the information age. A gallery of black-and-white photographs reveals the burgeoning influence of the telegraph on daily life. One compelling 1870 image depicts a “telegraph office in Philadelphia,” where a man intently sits “at a wooden console, typing out messages to the distant corners of the country.” This machine, powered by Morse code, represented a monumental leap in communication speed.

Indeed, this “new communication technology made news travel at ‘the speed of light’ and changed the way people conducted business.” Information that once took weeks or months to traverse the continent could now be transmitted in mere minutes, dramatically impacting commerce, journalism, and personal correspondence. By 1875, “telegrams becoming more popular and efficient” signified a cultural shift towards instantaneity, fostering a more interconnected nation.

Alongside the telegraph, the art of photography was also undergoing significant innovation. A notable 1865 “studio portrait of a family” captured in a “recently invented ‘portrait photography’ style” offers a glimpse into how Americans began to preserve their likenesses. While early cameras were “cumbersome but revolutionary,” they set the stage for a profound change in visual culture. The context notes that the introduction of the Kodak box camera just a few years later, in 1888, would “democratize photography and make everyday moments more easily preserved.”

The late 1870s also saw the promise of an even greater communication revolution. In 1876, “Alexander Graham Bell patented the telephone,” an invention that would “allow people to speak across long distances and revolutionized modern communications.” This visionary development, leading to the founding of the Bell Telephone Company, foreshadowed a future where voice communication would become ubiquitous, profoundly reshaping social interaction and business, and serving as a direct ancestor to our modern global communication networks.

5. Women in the Industrial Age: Shifting Roles and Labor

The photographs from the 1870s also provide an invaluable, candid look at the evolving roles and societal expectations placed upon women during this transformative era. While traditional domestic roles remained prevalent, the burgeoning industrial boom began to offer new, albeit challenging, avenues for women outside the home. A striking 1873 image captures a “woman in a mid-western factory—her hair pulled back in a bun,” a powerful visual testament that “the industrial boom did not leave her entirely confined to the home.”

This entry into the industrial workforce, particularly in factories in places like New England, marked a significant departure from previous norms. Although these positions were often “low-wage,” this early participation by women in formal labor was crucial, as it “helped spark future movements for labor rights.” It represented the tentative steps towards greater economic independence and challenged deeply ingrained societal perceptions of women’s capabilities and their place in the public sphere, sowing seeds for future social change.

Despite these shifts in the workplace, women’s fashion in the 1870s maintained a distinct formality and elegance that spoke to prevailing social aesthetics. “Women’s dresses tended to swoop towards the back and bunch around the buttocks,” creating dramatic silhouettes, and “it was also common that the dress fell flat against the abdomen.” The “princess waistline, which was achieved by wearing a tight corset, was also popular during this time period,” emphasizing a constrained, yet elaborate, style that contrasted with the physical demands of factory work.

These contrasting images—of women laboring in factories and simultaneously adhering to the rigid standards of Gilded Age fashion—highlight the complex tapestry of life for American women 150 years ago. They were navigating a society that was both opening new doors in the workplace while still imposing strict expectations on appearance and social conduct, reflecting a period of profound transition where traditional values clashed with the realities of industrial modernity.

Read more about: America’s Grandeur and Grime: 10 Defining Epochs of Progress and 5 Persistent Shadows

6. African American Communities: Building New Lives Post-Reconstruction

The decade following the Civil War and the abolition of slavery presented a complex and often contradictory landscape for African Americans, characterized by both newfound freedoms and persistent systemic challenges. Poignant photographs from this era offer crucial insights into the arduous process of building new lives and communities amidst lingering racial tensions. One particularly moving image captures a “young Black family in Ohio,” a vital inclusion that highlights an “often overlooked narrative” of resilience and determination in the face of adversity.

Education emerged as a cornerstone of progress and empowerment for these communities. An 1878 photo depicting a “Black schoolteacher in a rural Alabama town” vividly illustrates the “newly formed schools that were part of the Freedmen’s Bureau’s educational efforts.” These schools, established to provide education to formerly enslaved people, represented a profound commitment to self-improvement and future generations, acting as a beacon of hope where “education became a cornerstone for African American communities in the face of Jim Crow laws that would rise later.”

Legally, significant strides had been made: slavery was “made illegal in 1865 by the ratification of the 13th Amendment,” and the “US government passed the 15th Amendment” in 1870, which “granted African Americans the right to vote.” However, the promise of these amendments was severely curtailed in practice. The context explicitly states that “many were still unable to do so due to other discriminatory laws in place,” highlighting a deeply entrenched resistance to racial equality that would persist for decades.

The “Civil Rights Act of 1875” briefly offered a glimmer of hope by “prohibiting discrimination against African Americans in public places, including transportation and accommodations.” Yet, its impact was tragically short-lived, as it was “declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court just eight years later.” This legal setback, coupled with “multiple practices… implemented to stop Black people from exercising their right to vote,” meant that “African Americans were free, but in many ways, they were disfranchised,” forced into “squalor,” and would endure “nearly 100 years before many people of color could exercise their right to vote.” These images and narratives reveal a society grappling with the profound moral and social questions unleashed by emancipation, with a long and difficult road ahead for true equality.

Having explored the foundational shifts that redefined America in the 1870s, our journey now takes us deeper into the fabric of daily life, examining the subtle yet profound changes that shaped families, communities, and individual experiences across the nation. From the intimate settings of homes to the vibrant new arenas of leisure, we uncover how Americans adapted and thrived in an era of unprecedented transformation.

7. Changing Family Structures: Adapting to New Realities

The 1870s heralded a monumental shift in the very structure of American families, driven largely by the relentless march of the Second Industrial Revolution. Before this era, families predominantly resided on farmland, their lives intricately woven with the rhythms of the land, making a living directly from the soil. This deeply rooted agrarian lifestyle was the bedrock of American society for generations.

However, the magnetic pull of urban centers began to exert an irresistible force. A dramatic demographic migration saw millions of people leaving their rural homesteads and moving to burgeoning cities between 1870 and 1920. This exodus was motivated by the promise of factory jobs and new economic opportunities, fundamentally altering the traditional family dynamic and setting the stage for a more industrialized way of life.

Yet, this urban migration came with its own set of profound challenges. As cities swelled with new inhabitants, daily life often became alarmingly crowded and, for many, deeply unsafe. Historic photographs and reports from the time illustrate how New York City’s streets, for instance, were crammed with people, leading to the rapid proliferation of tenement housing. These cramped, multi-family dwellings often packed entire families into single-room apartments, where most endured squalor and precarious living conditions. The New York Public Library poignantly reported that it was “all very dense, very crowded, and unregulated — conditions that fostered disease and inhumane living conditions.”

Simultaneously, another significant movement reshaped family destinies: the enduring push westward. With the completion of the transcontinental railroads after the Civil War, vast stretches of open land became accessible, drawing countless families seeking to settle and farm. While popular imagination often conjures images of daring cowboys, the reality, as debunked by the Library of Congress, was a far tougher existence. These pioneers faced immensely challenging lifestyles, characterized by “long, hard hours of labor, poor living conditions, and economic hardship,” underscoring the resilience and sacrifice inherent in building a life on the frontier.

Read more about: A Comprehensive Guide to Family Structures: Understanding Diverse Forms, Functions, and Legal Frameworks for Informed Living

8. Waves of Immigration: Forging a New American Identity

Beyond the internal migrations within the United States, the 1870s witnessed an unprecedented influx of people from distant shores, fundamentally reforming the country’s demographics. Seeking refuge from poverty, political unrest, or simply hoping for a better life, thousands upon thousands of immigrants sailed to America, dreaming of opportunity and a fresh start. This surge of new arrivals would forever reshape the nation’s cultural and social landscape.

The scale of this human tide was immense. Between 1870 and 1900, a staggering 12 million people immigrated to the United States, according to the Library of Congress. These newcomers primarily hailed from European nations, with the majority arriving from Germany, Ireland, and England. Their diverse languages, traditions, and skills flowed into the growing cities and expanding farmlands, enriching the burgeoning American mosaic.

For many, the gateway to this new world was New York City’s Ellis Island, where more than 70% of immigrants officially entered the US. The experience of passing through this iconic port became a defining chapter in countless family histories, a moment of both apprehension and profound hope. These waves of immigration, while presenting challenges of assimilation, ultimately forged a more diverse and vibrant American identity, contributing immeasurably to the nation’s rapid development and cultural tapestry.

Read more about: Boston’s Unconventional Blueprint: Exploring the Quirks and Hidden Lore of a City Forged by Time

9. Education Takes Root: The Rise of Public Schooling

In the wake of profound societal changes, the commitment to public education experienced a remarkable surge in the 1870s, marking a significant departure from earlier priorities. Prior to 1870, formal public education had not been a widespread national focus, with many children learning through informal means or familial instruction. However, a growing national consciousness recognized the inherent value of an educated populace.

This recognition translated into tangible growth: between 1870 and 1900, attendance at public schools across the country doubled. The rapid influx of immigrant families also played a crucial role, creating an urgent need for accessible education. Public schools became vital instruments of assimilation, providing a common ground for children from diverse backgrounds and ensuring that the next generation could participate meaningfully in American society.

A typical public school of the era was often a one-room schoolhouse, serving children of all ages within a community. In these humble settings, students received instruction in foundational subjects such as math, reading, writing, geography, and history. Yet, for families grappling with extreme poverty, the ideal of education often clashed with economic necessity, sometimes compelling children to forgo schooling altogether and instead join the workforce to contribute to their family’s finances.

10. The Innocence of Childhood: Simple Joys and Homemade Wonders

Amidst the industrial bustle and societal shifts, childhood in the 1870s retained an essence of simplicity and ingenuity, often characterized by play that harnessed imagination and readily available materials. When not engaged in their studies or contributing to household chores, children found joy in games and toys that reflected the era’s resourcefulness.

Many of the toys that children cherished were lovingly crafted by their own parents from items found around the house. Rag dolls, for instance, were incredibly popular, fashioned from scraps of fabric and imbued with character through simple stitching. These homemade treasures were often central to imaginative play, fostering creativity in a world without mass-produced plastic playthings.

For families with greater financial means, the world of toys expanded to include more elaborate, handcrafted items. Wealthier children might have enjoyed intricately made dolls, often imported and sometimes fashioned from china, alongside miniature train sets or meticulously sculpted toy soldiers. These items, though still requiring manual skill in their creation, offered a glimpse into a more privileged childhood experience. Interestingly, it was also quite common for children’s playtime to be intertwined with spiritual and moral lessons, with toys sometimes designed to represent stories and characters from the Bible, reflecting the strong religious undercurrents of the age.

11. Fashion of an Era: Elegance and Formal Grandeur

The 1870s ushered in a distinct era of fashion, characterized by an elegance and formality that spoke volumes about prevailing social aesthetics and the burgeoning wealth of the Gilded Age. Women’s attire, in particular, was marked by dramatic silhouettes and intricate detailing, creating a look that was both sophisticated and visually striking.

According to the Fashion Institute of Technology, women’s dresses during this period famously tended to “swoop towards the back and bunch around the buttocks,” creating a pronounced bustle effect. This elaborate shaping at the rear was a defining characteristic, often contrasted with a front that “fell flat against the abdomen,” presenting a unique and elongated profile. The overall impression was one of stately grace and controlled volume.

Underneath these voluminous dresses, the “princess waistline” was a highly sought-after silhouette, achieved through the ubiquitous tight corset. This foundational garment cinched the waist, emphasizing an hourglass figure and contributing to the era’s ideals of feminine beauty, despite the physical restrictions it imposed. The intricate construction and layered fabrics of these garments were a testament to the skill of dressmakers and the meticulous standards of the time.

Menswear, too, embraced a formal aesthetic. Gentlemen of the era were typically seen in tailored suits, reflecting a sense of decorum and professional bearing. It was also a common sight to see men accessorizing their formal ensembles with canes or walking sticks, which served less as practical aids and more as symbols of status and refined taste, completing the dignified look of the Gilded Age man.

Read more about: Investor Alert: These 10 Luxury Cars Become Depreciating Assets Once They Hit 5 Years Old

12. Leisure and Sports: The Birth of American Pastimes

As the 1870s progressed and a middle class began to emerge, society’s increasing interest in leisure brought about the exciting birth and popularization of several American pastimes that would eventually become integral to the nation’s cultural fabric. Beyond the demands of work and domestic life, Americans sought out new forms of recreation, laying the groundwork for modern sports and entertainment.

Cycling, for instance, began its journey 150 years ago, initially gaining traction as a novel form of transport and recreation. While its full national craze would erupt later in 1890, particularly as women embraced bicycles for newfound freedom of mobility, the seeds of its popularity were firmly planted in the 1870s, symbolizing an early shift towards active leisure.

Tennis also soared in popularity, particularly among the upper and middle classes. Originating in England as lawn tennis, the sport quickly spread across the United States throughout the decade, with the New Orleans Lawn Tennis Club—widely recognized as the first of its kind in the US—being founded in 1876. Alongside tennis, golf also became a favored pursuit among the more affluent, further illustrating the diversifying recreational landscape.

Baseball, already having emerged a few decades earlier, truly gained momentum across various US cities during the 1870s. Following the first official game held in Hoboken, New Jersey, in 1846, the sport solidified its professional standing with the creation of the National League in 1876 by William Hulbert, then an executive and future president of the Chicago White Stockings. This institutionalization paved the way for baseball to become America’s beloved national pastime.

The burgeoning interest in leisure also led to other significant cultural milestones. The first Kentucky Derby, an event that would become an enduring American tradition, was proudly inaugurated in 1875 in Louisville, Kentucky. Simultaneously, shooting sports garnered considerable attention, leading to the founding of organizations like the Massachusetts Rifle Association in 1875, hailed as “America’s oldest active gun club,” and the National Rifle Association a few years prior in 1871, indicating a growing enthusiasm for organized competitive shooting.

Concluding Reflections: A Nation in Constant Motion

What ties all of these images and narratives together is a powerful story of transformation: an America emerging from the shadows of war, ceaselessly expanding its physical borders, and eagerly experimenting with new technologies that would ultimately weave the country into an increasingly interconnected whole. This collection of photographs and accompanying historical insights does far more than simply display nostalgic snapshots; it carefully contextualizes each frame, drawing upon the rich archives of the Library of Congress, the Smithsonian’s specialized portals, and the National Archives’ primary documents. Together, these invaluable resources meticulously paint a holistic and nuanced picture of life in the United States 150 years ago—a complex, at times uncomfortable, yet undeniably foundational period in the country’s enduring story.

These remarkable photographs, indeed, act as vivid portals. As we delve into the embedded histories they represent, we are consistently reminded that the 1870s were as much about the exhilarating promise of progress as they were about the harsh realities of a society navigating immense transition. The indelible legacy of this era—from the vast railway networks that physically bound a continent, to the powerful industrial factories that radically reshaped labor, and the revolutionary new forms of communication that dramatically accelerated the flow of news—still resonates profoundly. These echoes are discernible in the very infrastructure, culture, and intricate social dynamics that define modern America. For those of us living in a world where virtually everything is just a click away, these profound old images serve as a potent reminder of a time when the “click” was a very different sound: perhaps the rhythmic tap of a hammer driving a rail spike, the faint pulse of Morse code traversing a telegraph wire, or the seemingly endless stretch of a newly laid rail line carrying a nation towards its future.