Cartoons, for many of us, are the vibrant, imaginative tapestries of our childhoods. They’re the source of countless laughs, invaluable lessons, and unforgettable characters who danced, flew, and sang their way into our hearts. Yet, beneath their cheerful exteriors and playful facades, the world of animation holds a complex history, riddled with behind-the-scenes controversies, difficult decisions, and the often-unseen forces that have shaped what we watch, and sometimes, what we don’t. It’s a journey into the intricate dance between artistic freedom, cultural sensibilities, and public responsibility.

We’re not just talking about silly gags or minor edits here. We’re diving deep into the reasons why some of animation’s most iconic figures and memorable moments have been altered, pulled, or outright banned. This isn’t merely about preserving an illusion; it’s about understanding how societal values evolve and how powerful figures, contracts, and public outcry can impact a character’s destiny or a voice actor’s career. From contractual shackles to offensive stereotypes, the stories behind these changes are often more revealing than the animations themselves.

So, let’s pull back the curtain and explore some truly fascinating, and at times uncomfortable, chapters in cartoon history. We’ll discover how the voices we hear, and the characters we see, are products of their time, and how some have been reevaluated, silenced, or reshaped as the world moved on. Get ready to rethink some of your favorite animated memories as we uncover the hidden truths behind the pixels and the powerful decisions that echoed far beyond the screen.

1. **Adriana Caselotti: The Voice Behind Snow White’s Silence**Imagine lending your voice to one of the most successful films of all time, only to find your career seemingly stalled right after. That’s the intriguing, and somewhat heartbreaking, story of Adriana Caselotti, the original voice of Snow White. Her childlike, sing-songy vocals are still instantly recognizable more than 75 years later, yet her name doesn’t even appear in the credits of “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.” It’s a mystery that has fueled Hollywood legend for decades, making her perhaps the quintessential example of a voice “silenced” by circumstance or design.

The lack of credit wasn’t unusual for the era; it was 1937, and Disney didn’t actually credit voice actors until 1943. This was largely because “the famously image-conscious studio wanted to preserve the idea that its animated characters were actually real,” a strategy that makes a lot of sense when you consider the magical appeal of early Disney. However, the whispers and rumors go much deeper than just an uncredited performance. Hollywood legend has it that Walt Disney himself “contractually prohibited Caselotti from revealing her ‘secret identity’ or performing as Snow White, as well as doing any further film, TV and radio work for the rest of her career.” In essence, she was blacklisted, her unforgettable voice supposedly never to be heard again in new roles.

“Snow White” certainly marked both the beginning and, largely, the end of Caselotti’s showbiz career. Beyond a single voiceover line in “The Wizard of Oz” and a tiny singing part in “It’s a Wonderful Life,” major roles eluded her. The debate rages on: was it a genuine Disney ban, or simply that her voice was so uniquely identifiable that she struggled to land other jobs? After all, Walt Disney was a powerful figure, but would he truly sabotage an actor to preserve an animation? There’s a rumor that Disney actually owned the rights to Caselotti’s voice, with Jack Benny claiming Disney denied his request to have Caselotti on his radio show in 1938 because the studio “didn’t want to reveal the woman behind Snow White.”

What we do know from Caselotti’s “Snow White” contract doesn’t paint a picture of favorable terms. Hired at just 18, she was paid a total of $970 for about three years’ work, which translates to roughly $16,000 today. She and the Prince Charming voice actor even unsuccessfully sued Disney and RCA for a share of soundtrack-record profits in 1938. Despite these early struggles, Caselotti appeared to remain fiercely loyal to Disney throughout her life, even receiving the Disney Legend Award in 1994, and never publicly confirming any blacklisting scheme. Her story serves as a fascinating glimpse into the early power dynamics of Hollywood and the lengths studios would go to protect their animated magic.

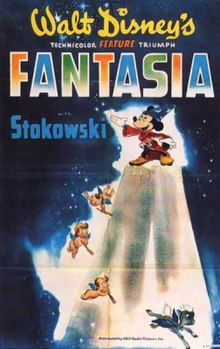

2. **Sunflower from Fantasia: A Stereotype Erased**Disney’s “Fantasia” is celebrated as a landmark in animation, a symphonic visual feast that pushed artistic boundaries. However, even this classic isn’t immune to the evolving lens of societal scrutiny. One character, in particular, has been quietly removed from later versions of the film, highlighting Disney’s shift toward more conscientious portrayals in media. We’re talking about Sunflower, the racially stereotyped centaur who once featured prominently in the film.

Originally, Sunflower was depicted with exaggerated features and placed in a subservient role, a visual representation that today is undeniably problematic. These caricatures, commonplace in early animation, were designed to evoke humor through offensive stereotypes, reflecting a deeply ingrained bias prevalent in the entertainment industry of the time. The context notes that such characters were “created with exaggerated features and portrayed in a subservient role,” a clear signal of their problematic nature.

As public awareness about racial representation grew and societal views evolved, these depictions became increasingly untenable. Disney, recognizing the need to align its content with modern sensibilities, took action. In 1963, Sunflower was removed from the film, a significant edit that, while subtle to a casual viewer, marked a powerful shift in the studio’s approach to racial sensitivity.

This decision wasn’t just about removing an offensive image; it was a conscious effort to acknowledge past mistakes and move towards more inclusive storytelling. Sunflower’s erasure from “Fantasia” stands as a potent example of how historical artifacts in animation are reevaluated, and sometimes reimagined, to reflect a commitment to diversity and respect for all audiences. It’s a reminder that even timeless classics aren’t immune to the call for cultural awareness.

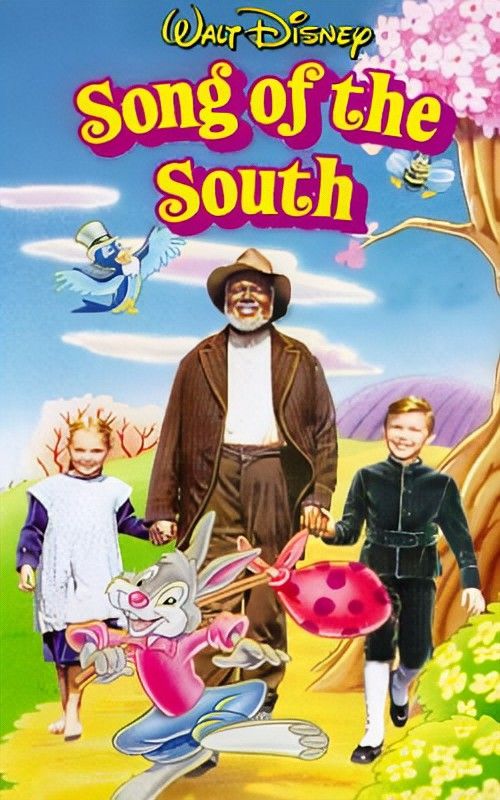

3. **Various Characters from Song of the South: The Plantation’s Lingering Shadow**Speaking of Disney classics facing intense scrutiny, few films provoke as much debate as “Song of the South.” Released in 1946, it was groundbreaking for its technical innovations, seamlessly blending live-action with animation and introducing the beloved character of Br’er Rabbit and the catchy tunes like “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah.” Yet, despite its technical merits and popular songs, the film has become a touchstone for discussions about problematic historical media, due to its controversial portrayal of African Americans and an idealized depiction of plantation life.

The film has faced “ongoing criticism for its portrayal of African Americans and idealized depiction of plantation life.” This isn’t just a minor complaint; it’s a fundamental challenge to the film’s narrative, which is seen by many as romanticizing the antebellum South and glossing over the brutal realities of slavery. Characters like Uncle Remus, while perhaps intended to be benevolent, are viewed through a lens of racial caricature that reinforces harmful stereotypes, presenting a sanitized and nostalgic view of a deeply painful historical period.

Due to these profound concerns, Disney has made the significant decision to largely withhold the film from release. Unlike some other controversial animations that have received edits or content warnings, “Song of the South” remains largely locked away in the Disney vault. This choice reflects a broader conversation about responsibly addressing historical media that, despite its artistic achievements, carries a heavy burden of racial insensitivity. It highlights the complex ethical dilemma between preserving a historical film and acknowledging its potential to perpetuate harmful narratives.

The withholding of “Song of the South” prompts important questions about how we, as a society and as an animation industry, grapple with problematic content from the past. It underscores the ongoing tension between celebrating cultural heritage and condemning offensive portrayals, demonstrating that some animated works carry an impact far beyond their original intent.

4. **Bosko from Looney Tunes: The Pioneering Caricature**Before Bugs Bunny or Daffy Duck tap-danced their way into our hearts, there was Bosko. He holds the esteemed title of being “one of the first stars of Warner Bros. cartoons,” a true pioneer in the golden age of animation. With his undeniable musical talent and an ever-optimistic spirit, Bosko danced and sang his way onto screens, captivating early audiences with his vibrant performances and contributing to the very foundation of what would become the iconic Looney Tunes style.

However, Bosko’s legacy is, unfortunately, intertwined with a darker aspect of animation history: racial caricatures. The context explicitly states that his “design drew from racial caricatures of the time.” This isn’t just a casual observation; it refers to the unfortunate practice in early animation of exaggerating features and mannerisms commonly associated with racist minstrel shows. These portrayals, while accepted by some audiences at the time, are deeply offensive by modern standards, perpetuating harmful stereotypes and dehumanizing caricatures.

As societal awareness and cultural sensitivities evolved, the problematic nature of Bosko’s design became impossible to ignore. The animation industry, along with broader society, began to reckon with these offensive depictions. This growing understanding ultimately led to Bosko’s eventual retirement. He, along with other characters from that era, became a symbol of a past that the industry needed to move beyond, highlighting the enduring impact of artistic choices on cultural perception.

Bosko’s story serves as a stark reminder of how pioneering creations can also carry the weight of historical insensitivity. It illustrates the journey of animation from a less regulated, often racially insensitive, form of entertainment to an industry increasingly striving for inclusivity and responsible representation. His retirement was a quiet acknowledgement of changing times and a step, however small, towards a more equitable animated landscape.

5. **The Censored Eleven: A Troubling Legacy of Racial Caricatures**If Bosko was an early indicator, then “The Censored Eleven” represent a full-blown chapter of reckoning in animation history. These aren’t just one-off controversial characters; they encompass “eleven notorious Looney Tunes shorts” that collectively form a complex and uncomfortable part of Warner Bros.’ past. While many might remember them for their groundbreaking animation techniques, their content is far more infamous for the deeply offensive racial stereotypes they depicted.

These cartoons, created during a different era, often relied on crude and demeaning portrayals of various ethnic groups, particularly African Americans. They utilized exaggerated physical features, mocking dialects, and stereotypical situations that contributed to harmful narratives. It’s a stark illustration of how animation, a medium often seen as innocent and lighthearted, could be used to perpetuate bigotry and prejudice. The shorts were “noted for their groundbreaking animation techniques, yet they depicted very offensive racial stereotypes,” a contradiction that makes their legacy all the more challenging.

The controversies surrounding “The Censored Eleven” grew so significant that they were eventually pulled from distribution. They represent a period when propaganda cartoons featuring “overt racism or demonization of enemy nations” were embraced, but later faced heavy criticism. This was not a minor edit; it was a decision to actively withhold these cartoons from public viewing, acknowledging that their content was too harmful to continue circulating without context.

Today, while these shorts remain culturally and historically significant for understanding the evolution of early animation, they are “no longer widely broadcast or included in standard DVD or streaming collections.” The decision to classify them as “censored” and remove them from general circulation underscores the ongoing debate about preserving problematic historical material versus preventing the normalization of hateful depictions. They stand as a powerful, albeit regrettable, monument to the industry’s past and the perpetual need for critical reevaluation.

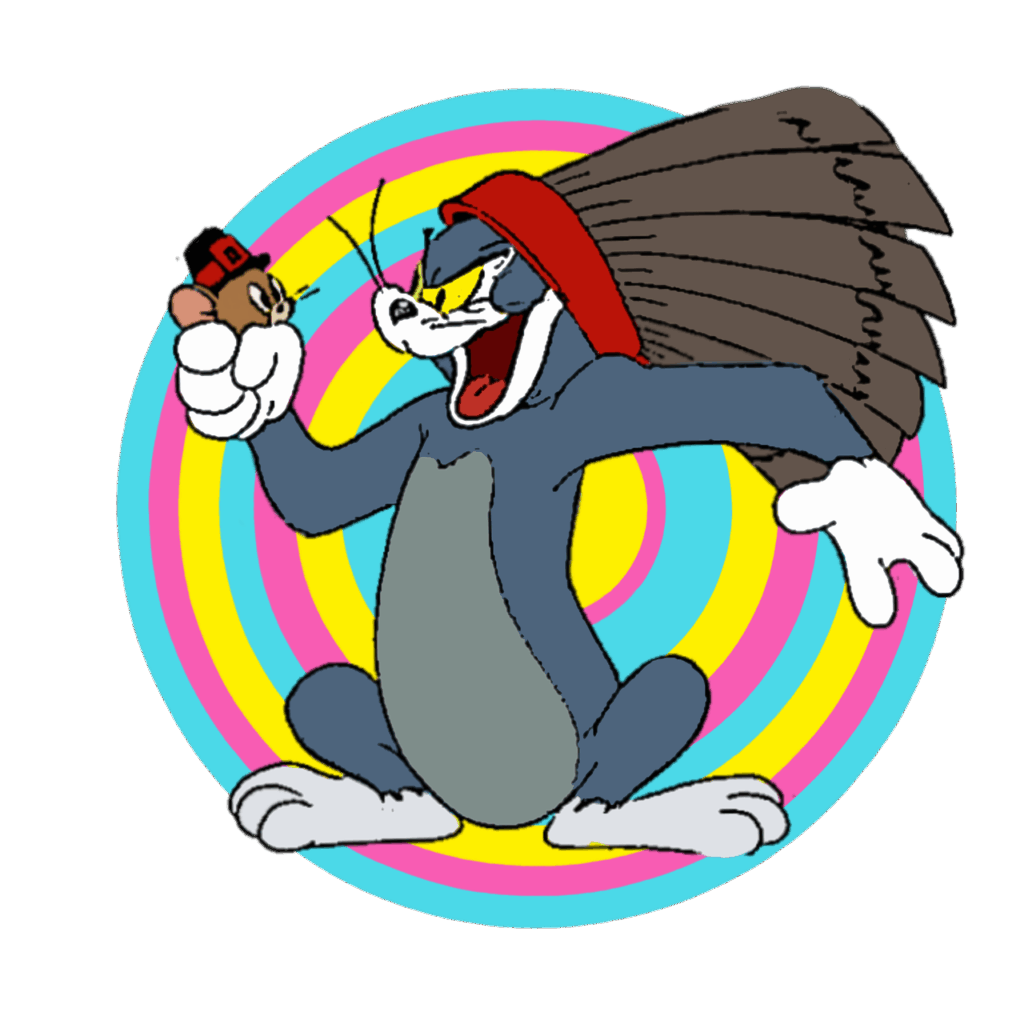

6. **Mammy Two Shoes from Tom and Jerry: The Unseen Housekeeper**For many who grew up watching the classic antics of Tom and Jerry, the figure of Mammy Two Shoes is instantly recognizable, even if often only partially seen. As the housekeeper, she was frequently heard “admonishing the mischievous duo in a thick Southern accent,” her voice and her legs often being the most visible parts of her presence. She served as the long-suffering foil to the cat and mouse’s chaotic escapades, but her character carried a much heavier weight of cultural baggage than her animated counterparts.

Her portrayal quickly drew criticism, primarily because her “character design was criticized for reinforcing racial stereotypes.” Mammy Two Shoes was a quintessential example of the “mammy” archetype, a stereotypical Black female character often depicted as overweight, domestic, and subservient. These portrayals, common in early 20th-century media, contributed to deeply entrenched and offensive caricatures of African American women. The thick Southern accent, the apron, and her role in the household all fed into a harmful, one-dimensional image.

As cultural sensitivities evolved and civil rights movements gained momentum, the problematic nature of such characters became increasingly undeniable. Audiences and critics began to challenge these depictions, recognizing their role in perpetuating bigotry. The presence of Mammy Two Shoes in “Tom and Jerry” thus became a focal point for discussions about racial representation in popular culture, pushing networks and studios to reevaluate their content.

While the show itself was not banned, her character was largely phased out, or her appearances heavily edited, in later broadcasts and versions of “Tom and Jerry.” This shift reflected a broader industry movement away from explicitly racist caricatures, opting instead for less problematic depictions. Mammy Two Shoes stands as a potent symbol of how even beloved characters can embody harmful stereotypes, and how public pressure and changing societal norms can necessitate their quiet, or sometimes not-so-quiet, disappearance from our screens. Her story is a testament to the idea that sometimes, the most unseen characters can have the most profound, and uncomfortable, cultural impact.

Now that we’ve glimpsed the earliest shadows cast by censorship and industry decisions, let’s fast-forward to the evolving landscape of modern animation. The journey from problematic voice contracts and overt racial caricatures leads us to a new set of challenges. These include unexpected health hazards, the continuous reevaluation of ethnic portrayals, characters removed for more nuanced behavioral issues, and the emotional and narrative impact when beloved voice actors step away. It’s clear that the discussions around cartoons only grow more intricate with time!

7. **Porygon from Pokémon: When Cartoons Become a Health Hazard**Remember when we thought cartoons were all fun and games? Well, for hundreds of viewers in Japan back in 1997, one particular Pokémon episode took a terrifying turn. The episode, featuring the digital Pokémon Porygon, was a normal part of the lineup until it aired, unleashing an unexpected and deeply concerning health crisis. It truly highlighted how the technical aspects of animation could have unforeseen, severe consequences.

What happened next was unprecedented: hundreds of viewers, many of them children, experienced seizures. The culprit? Intense flashing lights used during a particular scene in the episode. It was a shocking incident that quickly made headlines worldwide, forcing broadcasters, studios, and regulatory bodies to take a hard look at the potential dangers lurking within what was previously considered harmless entertainment. The sheer scale of the incident sent shockwaves through the industry.

Naturally, the episode featuring Porygon was immediately pulled from broadcast. This wasn’t just a minor edit; it was a complete and utter removal. The character itself, Porygon, along with its subsequent evolutions, was largely — if not entirely — excluded from the Pokémon series going forward. Imagine being a character essentially erased from existence due to a technical glitch! It definitely influenced stricter content regulations that continue to impact animation production even today.

This incident wasn’t just a one-off; it completely reshaped how animated content was produced and reviewed. It pushed content creators to implement far more stringent safety protocols, especially concerning visual effects and light patterns. The “Porygon incident” serves as a stark reminder that even in the whimsical world of cartoons, public safety remains paramount, demanding constant vigilance and adaptability from the industry.

8. **Hop Low from Fantasia: A Tiny Dancer’s Evolving Meaning**Speaking of Disney classics, “Fantasia” gave us many visually stunning sequences, including the charming mushroom dancer, Hop Low. With his tiny stature and whimsical performance, he truly captivated early audiences, adding a touch of magical grace to the film’s “Nutcracker Suite” segment. He was a memorable part of the film’s artistic grandeur and an undeniable highlight for many who watched it.

However, as cultural sensitivities evolved, so too did interpretations of various animated designs. Over time, Hop Low’s presence in the film began to draw scrutiny. It was not his performance itself, but rather “interpretations of cultural insensitivity in his design” that led to concerns. This points to how deeply rooted certain visual cues can be, and how they can evoke unintended meanings as society progresses and viewers become more critically aware.

In response to these growing concerns and the need for more inclusive representation, Disney made a subtle yet significant decision. Hop Low’s presence in later versions of “Fantasia” was notably reduced. This wasn’t an outright ban, but a conscious effort to minimize a character whose design, while perhaps innocent in original intent, no longer aligned with contemporary standards of cultural sensitivity. It’s another example of how even beloved elements of classic animation are reevaluated.

This quiet adjustment highlights the growing role of cultural awareness in revisiting classic animation. It demonstrates that even characters seemingly as innocuous as a dancing mushroom can become focal points in the ongoing conversation about media representation. It’s a testament to how past creative choices are continually filtered through the lens of modern sensibilities, shaping what we see and how we interpret animation’s rich history.

9. **The Siamese Cats from Lady and the Tramp: Slyness or Stereotype?**If you’ve ever hummed along to the tune of “We Are Siamese if you please,” then you’re familiar with Si and Am from Disney’s “Lady and the Tramp.” These twin Siamese cats were known for their catchy, albeit mischievous, song and their sly, conniving antics as they tried to get Lady into trouble. They were definitely memorable characters, adding a dash of villainous charm to the classic animated film, making them stand out in many viewers’ minds.

Yet, their memorable portrayal unfortunately “leaned into Asian stereotypes,” casting a distinct shadow over their otherwise charming mischief. From their distinctive accent and slanted eyes to their manipulative behavior, the characters unfortunately embodied problematic caricatures that were common in early 20th-century media. What was intended as a quirky antagonist ultimately became a subject of discussion regarding racial sensitivity.

This reliance on stereotypes, even in a seemingly lighthearted children’s film, contributed to harmful and reductive representations of Asian people. While perhaps not malicious in its original intent, the portrayal reinforced an “othering” that could be deeply unsettling for audiences of Asian descent. It’s a prime example of how stereotypes, once embedded in popular culture, can persist and carry weight far beyond their original context, affecting perception and understanding.

As public discourse around racial and ethnic representation intensified, the problematic nature of Si and Am’s depiction became increasingly evident. This led to their scenes being reevaluated and, in some cases, altered or removed in later adaptations or remakes of “Lady and the Tramp.” It’s a clear signal that even classic animated antagonists must evolve with societal understanding, challenging us to consider the enduring impact of seemingly small creative choices on broad cultural perception.

10. **Blackhawk from Blackhawk Comics and Cartoons: When Heroes Carry Harmful Baggage**Dive into the annals of comic book and cartoon history, and you’ll undoubtedly encounter the Blackhawk squadron. These valiant pilots were renowned for their heroic World War II escapades, flying through the skies and fighting for justice. They were the epitome of wartime bravery, thrilling audiences with their daring missions and becoming beloved figures in the patriotic landscape of the era. Their adventures truly captured the spirit of the times.

However, even these iconic heroes weren’t immune to the unfortunate practice of racial caricatures prevalent in their time. The squadron once included a character named Chop-Chop, whose depiction, sadly, was deeply rooted in such offensive tropes. This character’s design and portrayal often featured exaggerated, stereotypical features, reflecting a less enlightened era where such caricatures were widely, and uncritically, accepted in popular media. It’s a stark reminder of how historical biases seeped into creative works.

Over time, as societal values shifted and awareness of racial representation grew, these portrayals were rightly “seen as offensive.” What might have been considered “humorous” or commonplace during World War II was later recognized as dehumanizing and harmful. The perception of Chop-Chop, and similar characters, underwent a profound transformation, moving from lighthearted entertainment to a symbol of past insensitivities that needed to be addressed and corrected. The conversation around these characters became unavoidable.

This evolution in public consciousness eventually led to significant changes in how Chop-Chop was depicted, or even his eventual removal from the team, in later iterations and adaptations of Blackhawk. The move reflected a broader industry-wide effort to shed problematic stereotypes and embrace more respectful and inclusive character designs. The Blackhawk squadron’s story, therefore, isn’t just about wartime heroics; it’s also a valuable lesson in the ongoing journey toward responsible and ethical representation in media.

11. **Injun Joe from Tom Sawyer: A Menacing Image Reconsidered**Mark Twain’s “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer” is a foundational piece of American literature, and its various adaptations have brought characters like Injun Joe to life on screen. His presence in these stories was typically marked by a menacing aura, making him one of the most memorable — and fear-inducing — antagonists. He was designed to embody danger, a shadowy figure lurking in the background of Tom and Huck’s adventures, adding suspense and peril to their lives.

However, the creation of this menacing image came at a significant cost: his “portrayal drew heavily on Native American stereotypes.” This wasn’t merely a character; it was a character built upon reductive and harmful tropes associated with Indigenous peoples. These stereotypes often included depictions of savagery, untrustworthiness, and a lack of moral compass, contributing to a deeply troubling and one-dimensional image that perpetuated prejudice. It painted an entire group of people with a broad, inaccurate, and damaging brush.

The consequence of this heavy reliance on stereotypes was the creation of a “troubling image” that reinforced negative perceptions of Native Americans for generations of audiences. While the original intent might have been to craft a fearsome villain, the method chosen inadvertently perpetuated bigotry. This kind of characterization had real-world implications, contributing to the marginalization and misrepresentation of Indigenous communities in popular culture and beyond.

As sensitivity toward Indigenous representation began to grow and societal understanding of historical injustices deepened, adaptations of Tom Sawyer wisely started to “alter or remove his character.” This shift reflected a crucial move towards more respectful storytelling, acknowledging that some literary and cinematic villains, despite their narrative function, carried an unacceptable weight of racial insensitivity. It’s a powerful example of how classic stories must be reexamined and sometimes reimagined for modern, more aware audiences.

12. **Little Black Sambo: A Cherished Tale’s Racist Roots**”Little Black Sambo” is a story that, for many years, was widely “cherished for its adventurous narrative,” particularly among younger audiences. It told the tale of a clever boy who outwitted tigers, creating a whimsical and engaging adventure that seemed to captivate imaginations. The character’s bravery and resourcefulness were often highlighted, making it a favorite bedtime story or a quick read for children around the world, especially for its seemingly simple and charming plot.

Yet, beneath the surface of this adventurous narrative, “its origins are steeped in racial insensitivity.” The title character’s name itself, “Sambo,” is a deeply derogatory racial slur with historical ties to minstrel shows and the dehumanization of Black people. The book’s illustrations, often depicting Sambo with exaggerated features, also contributed to harmful caricatures that were pervasive and normalized in early 20th-century media, making the entire narrative deeply problematic.

So, while the character’s bravery and cleverness were indeed celebrated, this celebration was inseparable from the “imagery and language used in his stories [that] perpetuated harmful stereotypes.” The seemingly innocent tale inadvertently, or perhaps overtly depending on the edition, reinforced racist tropes that had long-lasting and damaging effects on the perception of Black individuals. It created a complex legacy where a positive message was intertwined with deeply offensive racial undertones.

Today, “Little Black Sambo” stands as a poignant example of how a story, once widely accepted and even beloved, can be utterly transformed by evolving cultural understanding. Its continued discussion serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of historical context and critical media literacy. It underscores the profound responsibility that creators and consumers alike bear in confronting and moving beyond media that, despite its charm for some, ultimately causes harm through its insensitive and racist underpinnings.

***

As we’ve journeyed through the intricate world of cartoon censorship, from the silent voices of early Disney stars to the modern complexities of Porygon’s health hazard and the ongoing reckoning with racial stereotypes, it’s clear this isn’t a simple black-and-white issue. Cartoons, with their playful facades, hold an incredible real-world power, reflecting societal values and cultural shifts in ways we often don’t immediately realize.

Censorship acts as a mirror, showing us where we, as a society, draw our moral lines and how our collective understanding of what’s acceptable continually evolves. It reminds us that artistic freedom, while vital, often dances a delicate tango with public responsibility, especially when influencing young minds. As new platforms emerge and global audiences connect, these conversations about context, content warnings, and responsible representation will only grow louder.

Ultimately, the stories behind these banned or altered animated moments aren’t just about what we can or can’t watch. They’re about how we learn from our past, challenge our present, and collectively shape a future where animation continues to entertain, provoke, and inspire, all while fostering a more inclusive and thoughtful landscape. It’s a captivating, ongoing saga, reminding us that even the most whimsical of worlds has a serious side, constantly inviting us to think, discuss, and, most importantly, grow.