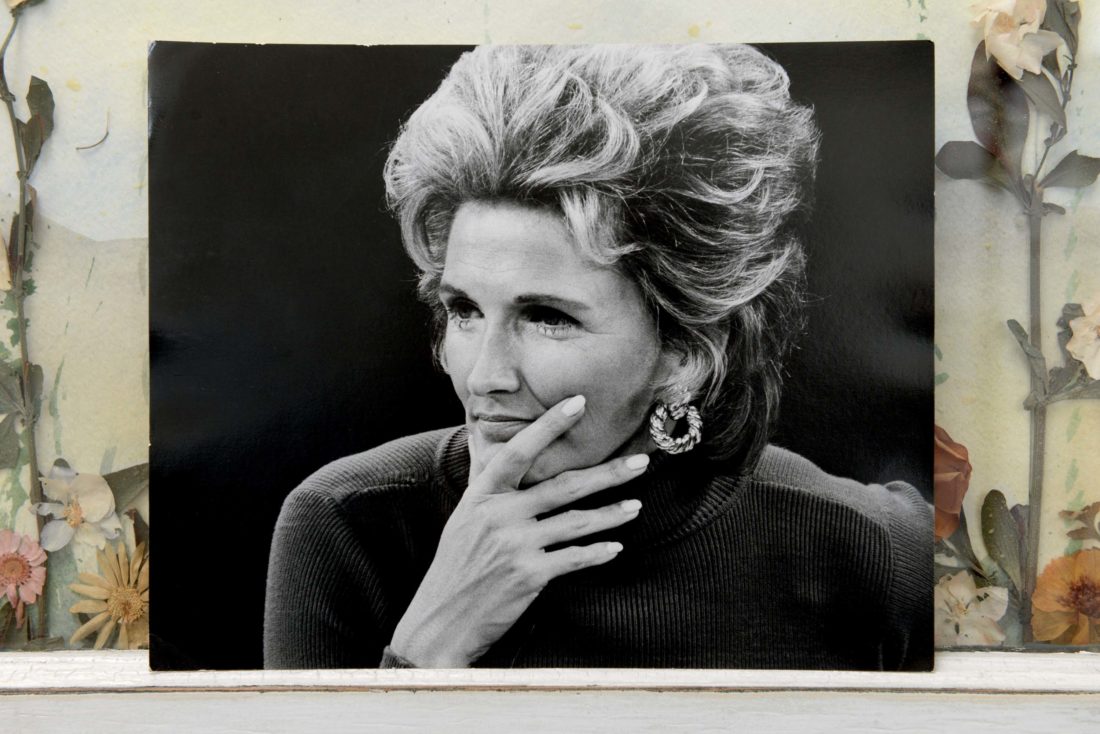

Barbara Howar, the best-selling author, astute television interviewer, and a gleefully nonconformist presence in Washington’s social circles, passed away on August 2 at the age of 89. She died in Los Angeles, where she had resided for the past two decades, with complications from dementia being the cause, as confirmed by her daughter, Bader Howar.

Ms. Howar’s life was a testament to reinvention, marked by a sharp wit and an unwavering commitment to candor that captivated the nation. She seamlessly transitioned from a celebrated Georgetown hostess during the height of the Swinging Sixties to an influential writer and broadcaster, leaving an indelible mark on both political and popular culture.

Her journey from a spirited Southern debutante to an “enfant terrible” of the capital, and later a national media personality, offers a compelling narrative of a woman who continually defied expectations and carved her own path. This article explores the multifaceted life of Barbara Howar, celebrating her unique contributions and the bold spirit that defined her.

1. **Early Life and North Carolina Origins**Barbara Stephanye Dearing was born on September 27, 1934, in Nashville, Tennessee, and spent her formative years growing up in Raleigh, North Carolina. Her family background provided a stable foundation, with her father, Charles Oscar Dearing, working as an engineering-industry sales manager, and her mother, Mary Elizabeth (O’Connell) Dearing, affectionately known as Buffy, managing the family affairs. Buffy, in particular, was described by Bader Howar as someone who could always be relied upon to support her daughter through emotional crises, even driving from Raleigh to Washington to do so.

During World War II, a pivotal moment in young Barbara’s life occurred, foreshadowing her future inclination for public recognition. She recounted dressing in a Women’s Army Corps uniform, provided by her mother, and standing along the highway, saluting military trucks bound for Quantico or Fort Bragg. A photograph captured her in this full uniform, saluting a convoy, and its publication in The Raleigh Times became one of her proudest moments.

Reflecting on this early experience, Ms. Howar herself wrote in her memoir that this incident was “probably the beginning of a deep and abiding love for personal recognition.” This early taste of visibility undoubtedly fueled her later ambitions, setting the stage for a life lived largely in the public eye. Her connection to North Carolina remained a significant part of her identity.

Before settling permanently in the nation’s capital, Barbara Howar first encountered Washington when she attended Holton-Arms. At the time, this institution was a finishing school in Washington, later relocating to Maryland, and Ms. Howar sometimes referred to it as a junior college. It was during this period that she fell deeply in love with Washington, a city that would become the backdrop for much of her remarkable career and social ascendancy.

Upon returning to North Carolina, she made her debut as a debutante, a traditional rite of passage in Southern society. Her initial professional steps included working for The Raleigh Times, her hometown newspaper, where she contributed society articles while also performing various menial tasks. These early experiences in journalism provided a foundation for her future writing endeavors.

2. **Ascension as a Washington Socialite**In 1957, Barbara Howar made the decisive move to Washington, D.C., a city she had grown to admire during her finishing school years. She arrived with what she described as limited assets, candidly noting in her memoir “a vague but cosmetically encouraged resemblance to Grace Kelly and six years of elocution lessons at Miss Bootsie MacDonald’s School of Tap and Toe.” Despite these self-effacing remarks, her charm and ambition soon propelled her into the heart of the capital’s social scene.

Her first professional step in Washington was securing a secretarial position on Capitol Hill, working with the House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce. This role provided her with an early vantage point into the intricate workings of D.C. power and society. It wasn’t long before her personal life also took a significant turn, further solidifying her place within the city’s elite circles.

In 1958, she married Edmond N. Howar, a prominent real estate developer who was a first-generation Arab American. Their wedding, as she recalled, “stunned family friends” back in North Carolina, who “almost expected him to come around on camelback,” highlighting the cultural differences and societal perceptions of the time. This marriage integrated her into a well-established Washington family.

By the mid-1960s, Barbara Howar had become an undeniable fixture in Washington high society. A 1965 article in Life magazine lauded her as “Washington’s most discussed, outspoken and photogenic society matron in decades,” a testament to her rapidly growing prominence and magnetic personality. Her Georgetown home became a vibrant hub for what was known as “Swinging Sixties entertainment,” attracting a diverse and influential crowd.

Another telling headline, this time from a 1966 Life magazine article, declared, “A Swinger Frugs Gaily Into the ‘Hostess Gap.’” This phrase perfectly encapsulated her dynamic presence, referencing the popular dance, the frug, and using “swinger” in its broader sense to describe her unconventional and lively approach to social life. Her status as a successful hostess was firmly established, though she would later express complex feelings about this label.

3. **The ‘Irreverent’ Personality: Defying D.C. Norms**Barbara Howar was anything but conventional, earning her a reputation as the “enfant terrible of the capital’s social scene.” Her defiance of established norms was not merely a superficial act; it was an intrinsic part of her character, manifesting in myriad ways that kept Washington society both fascinated and occasionally scandalized. She possessed a spirit that refused to be confined by the staid expectations of her era.

Her famously unorthodox behavior included audacious acts such as wearing pajamas to an embassy gala, a deliberate transgression of formal diplomatic protocol that underscored her irreverent spirit. On another occasion, she was known to drive an orange motorcycle through a Georgetown park, an image that further solidified her status as a flamboyant and unpredictable figure who relished challenging conventions.

Beyond her actions, Ms. Howar’s sharp, barbed wit was legendary, often delivered with a Southern drawl that only added to its charm and impact. She famously quipped about Henry Kissinger, one of the many diplomats and politicians who frequented her parties, stating, “Henry’s idea of is to slow the car down to 30 miles an hour when he drops you off at the door.” Such remarks showcased her keen observation skills and her refusal to shy away from provocative commentary.

Despite her immense success as a hostess, Ms. Howar candidly declared that she had little interest in being perceived as Washington’s “No. 1 hostess.” She explained this sentiment by noting that such a label often meant that “clever, fun people avoid you,” preferring to cultivate a genuine and engaging social circle rather than a purely status-driven one. This statement revealed a deeper desire for authentic connection over superficial acclaim.

Indeed, her uninhibited and outspoken nature was a defining characteristic throughout her life. People magazine once aptly described her as “one of the most uninhibited, outspoken women in Washington,” a title she certainly lived up to. Her willingness to speak her mind, often with a provocative edge, ensured that she was never a passive participant in any conversation or social gathering, making her a truly unforgettable personality.

4. **The Johnson White House Connection and Disengagement**Barbara Howar’s social ascent brought her into direct contact with the highest echelons of American power, including the Kennedy White House, where she socialized with the prominent family. Her engagement in national politics deepened significantly when she volunteered for President Lyndon B. Johnson’s 1964 campaign, a decision that would lead to a period of remarkable proximity to the presidential family.

During her time with the Johnson campaign, she grew exceptionally close to the president’s wife, Lady Bird Johnson, and their children. She actively participated in the campaign, notably accompanying Lady Bird on her whistle-stop tour through the South, an experience that forged a strong bond. So entrenched did she become that she was sometimes described as their unofficial fashion consultant, reflecting the trust and intimacy she shared with the First Family.

Her connections culminated in a moment of great personal significance: on the night of Johnson’s inauguration, she had the distinct honor of dancing the foxtrot with the president himself. Her duties within the Johnson circle expanded to include overseeing inaugural balls and planning the wedding of the president’s daughter, Luci Baines Johnson. For a brief period, she even found herself doing Lady Bird Johnson’s hair, illustrating the depth of her involvement.

However, this close association with the Johnson White House proved to be a fleeting chapter, as the family soured on Ms. Howar within a year, leading to her dismissal. According to a report in Life magazine, the acrimony stemmed from Ms. Howar gossiping about a $6,000 engagement party she was planning for Luci, an event that had not yet received formal approval from the family. This perceived breach of trust quickly fractured their relationship.

While Ms. Howar attributed the falling out to jealous White House staffers, others suggested the cause was rooted in rumors of her private love affairs. Regardless of the exact reason, this professional and personal setback inadvertently launched a new phase of her career. She transformed the experience into a lengthy article titled “Why LBJ Dropped Me,” published in Ladies’ Home Journal in 1968, in which she candidly shared stories about the family, including previously undisclosed details like the daughters’ Secret Service code names, Venus and Velvet. This piece marked her debut as a tell-all writer.

5. **Divorce and the Dawn of a Media Career**By 1967, a significant shift occurred in Barbara Howar’s personal life when she and her husband, Edmond N. Howar, divorced. After nine years of marriage, this separation marked not only the end of a relationship but also a profound turning point in her professional trajectory. It provided the impetus for her to pursue ambitions that extended far beyond the socialite status that had initially brought her fame in Washington.

At the relatively young age of her early 30s, Ms. Howar embarked on a remarkable reinvention of herself. No longer content to be solely defined by her role as a successful hostess, she strategically launched twin careers: one as a writer and another as a broadcaster. This pivot demonstrated her innate drive and her astute understanding of how to leverage her unique experiences and personality for a broader audience.

Her debut as an author was significantly propelled by her candid article, “Why LBJ Dropped Me,” published in Ladies’ Home Journal. This piece, which detailed her falling out with the Johnson White House, proved to be a pivotal stepping stone. Its success not only garnered national attention but also opened doors to further writing assignments, showcasing her talent for incisive commentary and engaging storytelling.

Building on this initial success, Ms. Howar began contributing essays and book reviews to prestigious publications such as The Washington Post and The New York Times. These contributions allowed her to hone her journalistic skills and establish her voice in print, transitioning from social commentary to more structured literary endeavors. Her distinctive perspective and sharp observations quickly found a receptive audience within these respected outlets.

This period of reinvention was characterized by a potent blend of courage and opportunism. She transformed a personal and professional setback—her dismissal from the Johnson circle and her subsequent divorce—into a springboard for an entirely new and impactful career in media. It was a testament to her resilient spirit and an early indicator of the lasting legacy she would forge as an uninhibited and influential public figure.

6. **”Laughing All the Way”: The Memoir’s Phenomenal Success**In 1973, Barbara Howar cemented her place in the literary world with the publication of her memoir, “Laughing All the Way.” This book was not merely a collection of personal anecdotes; it was an irreverent and gossipy account of Washington society, penned by an insider who was unafraid to expose its intricacies and eccentricities. Its candor resonated deeply with a public that, in the 1970s, increasingly embraced such unvarnished honesty.

The memoir’s impact was immediate and substantial, quickly becoming a fixture on The New York Times best-seller list, where it remained for several months. Its enduring popularity signaled a broader cultural appetite for personal narratives that pulled back the curtain on the lives of public figures and the machinations of power. Ms. Howar’s distinctive voice, combining wit with unflinching honesty, proved irresistible to readers.

Critics lauded the book for its unique blend of revealing detail and engaging prose. Charlotte Curtis, a reviewer for The New York Times, praised “Laughing All the Way” not only for its candor but also for its quality of writing. Ms. Curtis highlighted Ms. Howar’s “telling eye for detail,” her “ability to keep herself in perspective at least some of the time,” and her “graceful way with a story,” all while acknowledging that it contained “enough bigname trivia to keep her laughing all the way to the bank.”

Novelist Erica Jong, writing in the same newspaper, offered an equally enthusiastic endorsement, hailing the memoir as “a blast of clean air.” Jong further elaborated on its significance, describing it as “a book about politics that only a woman could have written, a book about power seen from the excellent vantage point of the boudoir, a book about deception and self‐deception at the top.” This perspective underscored the memoir’s unique contribution to political and social commentary.

Nora Ephron, in her 1975 book “Crazy Salad,” dedicated a chapter to Ms. Howar, adapted from an earlier Esquire article, titled “Crazy Ladies I.” In it, Ephron characterized “Laughing All the Way” as “almost a case study of a kind of woman and a kind of misdirected energy.” Yet, Ephron also found Ms. Howar’s earnest attempts to forge a new life and identity for herself “genuinely, and surprisingly, moving,” suggesting a depth beneath the surface irreverence that resonated with many.