In the annals of rock and roll, few voices burned as brightly and briefly as that of Janis Joplin. Her electrifying stage presence and raw, powerful mezzo-soprano vocals captivated a generation, cementing her status as one of the most iconic performers of her era. Yet, behind the public persona of the “Pearl” lay a complex individual grappling with profound personal demons, a journey that would tragically culminate in her sudden passing at the age of 27.

To truly understand Janis Joplin’s legacy and the precise circumstances leading to her untimely demise, we must delve beyond the headlines. We will journey through the pivotal moments of her life, from her early, formative years and the blossoming of her rebellious spirit to her meteoric rise to fame and the intense personal battles that often played out beneath the glare of the spotlight. This is a story of immense talent, relentless ambition, and heartbreaking vulnerability, all interwoven into the fabric of rock history.

This in-depth exploration seeks to paint a comprehensive picture, tracing the trajectory of an artist who dared to be different. It’s an investigation into the forces that shaped her, the choices she made, and the environment she navigated, offering a nuanced perspective on a life that ended far too soon, leaving behind an indelible mark on music and culture.

1. **Early Life and Formative Years: Port Arthur to UT Austin.**Janis Lyn Joplin was born in Port Arthur, Texas, on January 19, 1943, to Dorothy and Seth Joplin. Her parents noted that Janis, along with siblings Laura and Michael, seemed to require more attention, an observation that subtly shaped her early experiences and self-perception.

As a teenager, Joplin found kinship among social outcasts. Through them, she was introduced to blues artists like Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey, and Lead Belly, whom she credited as pivotal to her decision to sing. She began performing blues and folk music with friends at Thomas Jefferson High School, discovering her powerful voice.

High school was a challenging period, marked by ostracism and bullying. She recounted being taunted with cruel names. Struggling with her weight and severe acne, she often felt like a misfit. Despite social pressures, she asserted her individuality, stating, “I was a misfit. I read, I painted, I thought. I didn’t hate black people.”

After graduating in 1960, Joplin briefly attended Lamar State College of Technology before the University of Texas at Austin. Though she didn’t complete her studies, her distinctive personality shone brightly. A 1962 *Daily Texan* profile, “She Dares to Be Different,” noted her unconventional habits, like going barefoot and carrying her Autoharp.

At UT, she performed with the folk trio the Waller Creek Boys, honing her mezzo-soprano vocals. She also socialized with *The Texas Ranger*, the campus humor magazine. This Austin period allowed her to cultivate her artistic identity, embracing her unique path.

2. **First Foray into San Francisco: The Seeds of a Rebel.**Joplin cultivated a rebellious persona, inspired by blues heroines and Beat poets. Her first recorded song, “What Good Can Drinkin’ Do,” taped in December 1962, marked an early step, foreshadowing the raw authenticity defining her later work.

In January 1963, she left Texas, stating it was “Just to get away” and because “my head was in a much different place.” She hitchhiked with friend Chet Helms to North Beach, San Francisco, a deliberate break seeking an accepting environment.

While in San Francisco in 1964, Joplin collaborated with future Jefferson Airplane guitarist Jorma Kaukonen. They recorded several blues standards informally. This recording, including Kaukonen’s wife Margareta using a typewriter, was posthumously released as *The Typewriter Tape*, offering a raw glimpse into her early blues.

However, this initial San Francisco period also saw a significant increase in her drug use. Arrested for shoplifting in 1963, her substance consumption escalated. She acquired a reputation as a “speed freak” and occasional heroin user. She also heavily consumed alcohol, favoring Southern Comfort, indicating a deepening struggle.

By May 1965, severe effects of methamphetamine injections were evident; friends described her as “skeletal” and “emaciated.” Concerned, they persuaded her to return to Port Arthur, even hosting a party for her bus fare. Joplin later told *Rolling Stone*, “I didn’t have many friends and I didn’t like the ones I had.”

3. **A Brief Return to Texas: Seeking Stability and Education.**Upon her return to Port Arthur in spring 1965, Joplin’s parents were alarmed by her physical state; her weight had dropped to 88 pounds. This intervention prompted a significant, temporary lifestyle change. She committed to sobriety, adopted a beehive hairdo, and enrolled at Lamar University as an anthropology major.

Her sister, Laura, clarified that Joplin’s major at Lamar was social work. This suggests a desire to understand human behavior or contribute positively. Despite enrollment, she continued to nurture her musical passion, commuting to Austin to perform solo with her acoustic guitar.

During this period of attempted stability, Joplin became engaged to Peter de Blanc in fall 1965. Their relationship had begun toward the end of her first San Francisco stint. De Blanc visited Port Arthur to ask her father for her hand, and wedding plans commenced.

However, the engagement was fleeting. De Blanc, whose work required frequent travel, ended the relationship soon after. This personal setback, combined with underlying anxieties about her future, created a complex emotional landscape during a time she strove for a more conventional life.

From 1965 to 1966, Joplin regularly attended sessions with psychiatric social worker Bernard Giarritano. She expressed uncertainty about pursuing a singing career without relapsing into drug use. Joplin pondered the alternative: a life as a keypunch operator, “similar to all the other women in Port Arthur,” a future she found unappealing. She also recorded seven acoustic studio tracks during this year.

4. **Big Brother and the Holding Company: The Ascent of a Star.**In 1966, Janis Joplin’s distinctive, bluesy vocal style caught the attention of Big Brother and the Holding Company. This San Francisco-based psychedelic rock band was gaining recognition within the burgeoning hippie community of Haight-Ashbury, setting the stage for a pivotal moment.

Chet Helms, promoter and Joplin’s former hitchhiking companion, actively recruited her. He dispatched friend Travis Rivers to Austin, where Joplin was performing, to bring her back. Joplin initially misled her parents, implying Austin was her final destination for joining a band.

Joplin officially joined Big Brother on June 4, 1966. Her first public performance with the band took place at the Avalon Ballroom in San Francisco. Shortly after, her parents received a letter revealing her true location, highlighting her independent spirit.

Despite her return, Joplin initially maintained a strict stance on drug use. Sharing an apartment with Travis Rivers, she made him promise no needles would be allowed. This was tested when bandmate Dave Getz witnessed Rivers’ guests injecting drugs, causing Joplin to erupt. She screamed, “We had a pact! You promised me! There wouldn’t be any of that in front of me!”

The band faced early challenges, including being stranded in Chicago in August 1966 after a promoter ran out of money. Despite unsatisfactory initial recordings with Mainstream Records, Big Brother continued performing live. They eventually recorded ten tracks for their debut album in Los Angeles in December 1966, preceding wider recognition.

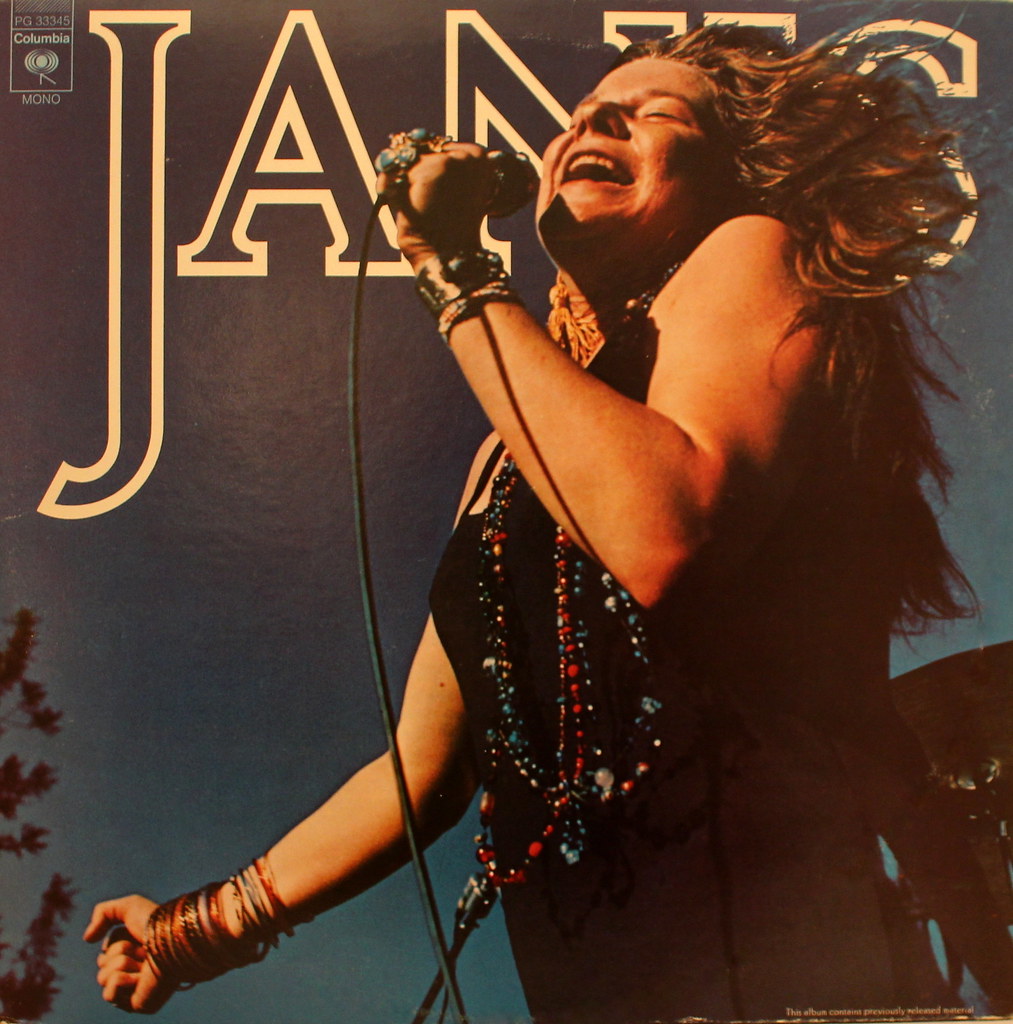

5. **Monterey Pop and “Cheap Thrills”: Breaking Through to Stardom.**Big Brother and the Holding Company’s debut studio album, *Big Brother & the Holding Company*, was released by Mainstream Records in August 1967. However, their electrifying performance at the Monterey Pop Festival in June that same year truly launched Janis Joplin into national prominence, making her an instant star.

Her scorching rendition of “Ball and Chain” at Monterey Pop showcased her raw, visceral power. This performance immediately distinguished her as a breakout artist within the psychedelic rock movement. Columbia Records, acquiring the band’s contract, featured “featuring Janis Joplin” on the re-released album cover.

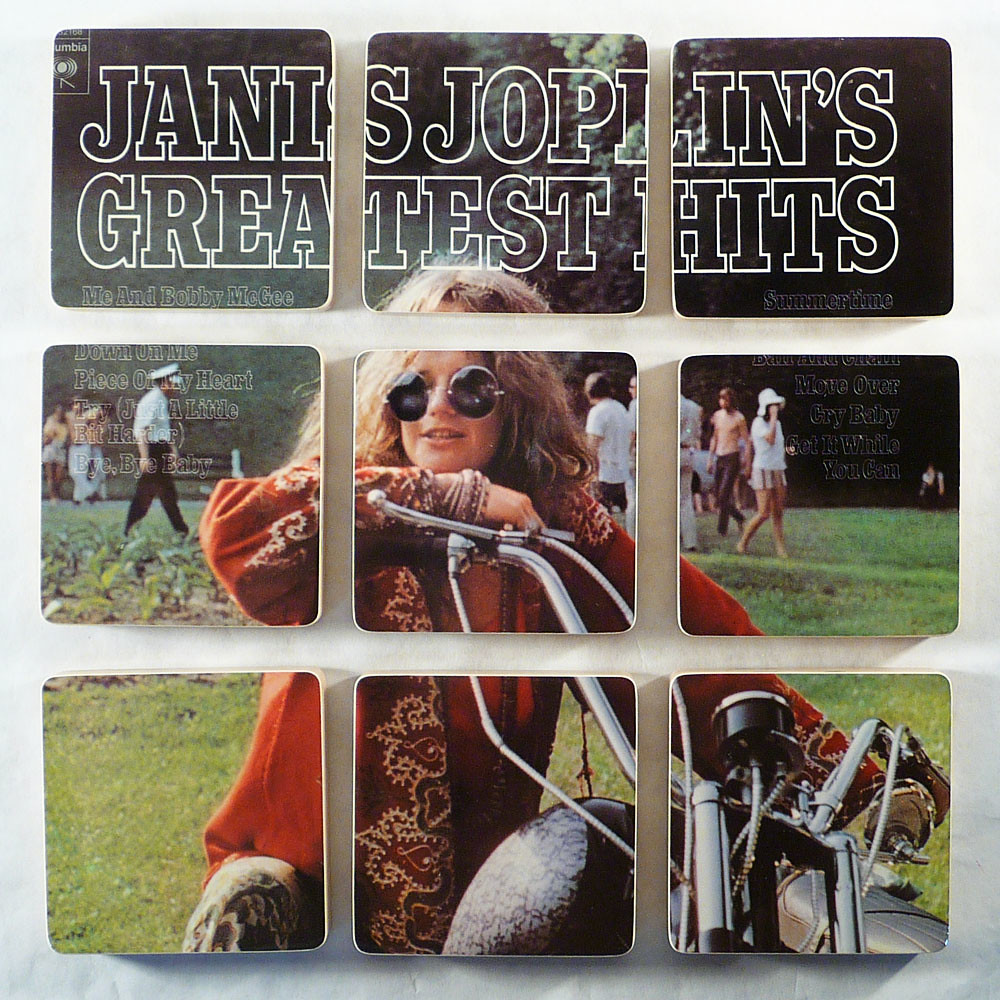

The debut album yielded several minor hits sung by Joplin, including her arrangement of “Down on Me,” alongside “Bye Bye Baby,” “Call On Me,” and “Coo Coo.” These early recordings demonstrated her powerful mezzo-soprano and impassioned delivery, drawing listeners into her blues-rock fusion sound.

The band’s subsequent album, *Cheap Thrills*, released in 1968, solidified their and Joplin’s iconic status. Mostly studio-recorded, “Ball and Chain” was live. Its raw quality, including a breaking drinking glass during “Turtle Blues,” contributed to its visceral appeal. *Cheap Thrills* quickly produced major hits like “Piece of My Heart” and “Summertime.”

The album’s success, coupled with the premiere of the *Monterey Pop* documentary in December 1968, unequivocally established Joplin as a bona fide star. *Cheap Thrills* rapidly ascended to number one on the Billboard 200, holding the top position for eight nonconsecutive weeks. This period marked the zenith of her collaboration with Big Brother.

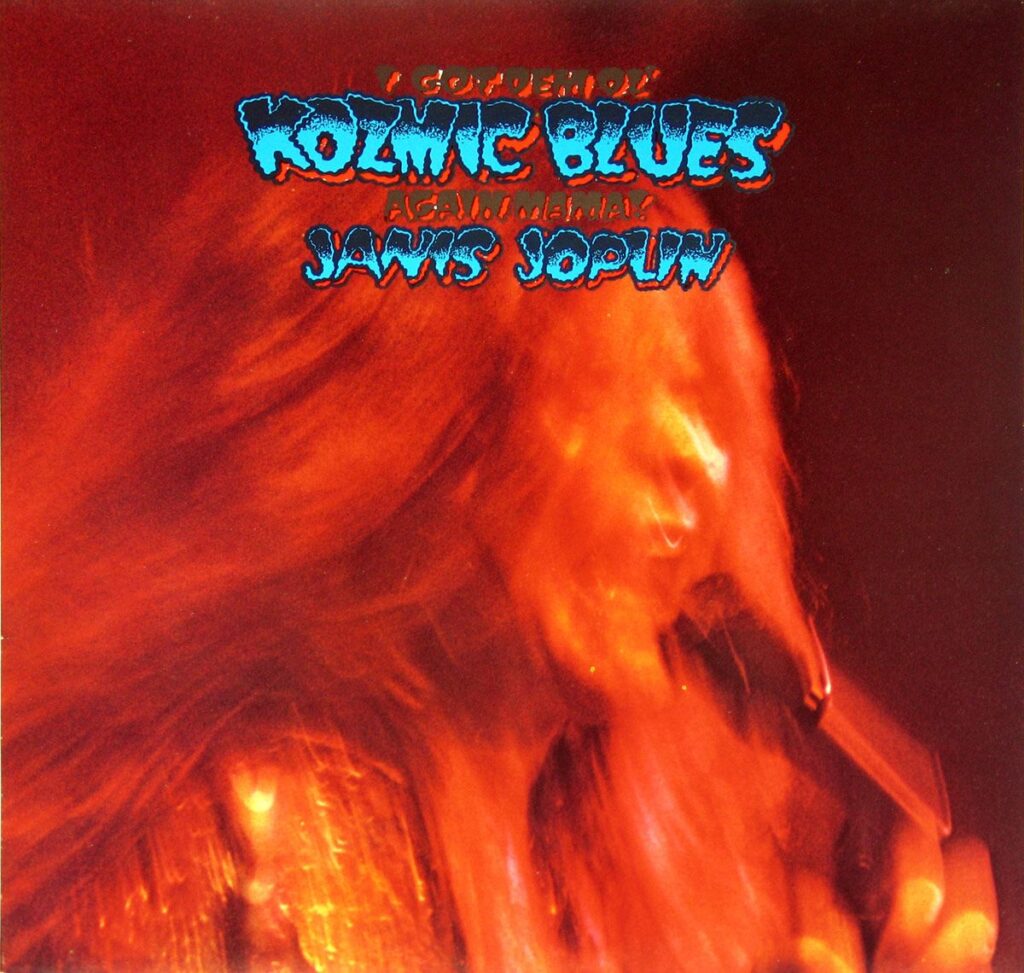

6. **The Kozmic Blues Band Era: Evolving Sound and Intensifying Struggles.**After parting ways with Big Brother and the Holding Company, Janis Joplin forged a new musical path, forming the Kozmic Blues Band. This ensemble included seasoned session musicians like keyboardist Stephen Ryder and saxophonist Cornelius “Snooky” Flowers, alongside former Big Brother guitarist Sam Andrew and future Full Tilt Boogie bassist Brad Campbell.

The band’s sound represented a stylistic shift, heavily influenced by Stax-Volt rhythm and blues (R&B) and soul bands of the 1960s, reminiscent of Otis Redding. This broadened musical palette showcased Joplin’s versatility and ambition to explore different sonic textures beyond raw psychedelia.

However, beneath this artistic evolution, Joplin’s personal battles with substance abuse intensified dramatically. By early 1969, reports suggested she was injecting at least $200 worth of heroin daily. Producer Gabriel Mekler actively shielded her from drugs and drug-using acquaintances during *I Got Dem Ol’ Kozmic Blues Again Mama!* recording.

Joplin’s performances with the Kozmic Blues Band in Europe were documented in films like *Janis*, featuring her arrival in Frankfurt and interviews in Stockholm and London. John Byrne Cooke, her road manager, detailed her persistent narcotic use, particularly during international tours, providing a somber account.

Released in September 1969, the *Kozmic Blues* album was certified gold but did not achieve *Cheap Thrills*’ commercial success. Critical reception was mixed; some critics found the new band a “drag,” while others celebrated Joplin’s “magic” and “first-rate musicians.” This division underscored tension between her artistic growth and public perception.

7. **Woodstock and its Aftermath: The Public Spotlight and Private Demons.**Janis Joplin’s performance at Woodstock, starting around 2:00 a.m. on Sunday, August 17, 1969, remains an indelible moment. Though she initially told her band it was “just another gig,” her helicopter ride with Joan Baez revealed the festival’s monumental scale. Baez recalled Joplin becoming “extremely nervous and giddy.”

A grueling ten-hour wait backstage, due to contractual obligations, proved detrimental. During this delay, Joplin succumbed to vulnerabilities, shooting heroin and drinking alcohol in a tent with friend Peggy Caserta. This ritual tragically underscored her escalating reliance on substances to cope.

Despite these challenges, Joplin delivered a potent performance, engaging spiritedly with the audience and responding to demands with an encore of “Ball and Chain.” Pete Townshend, witnessing her set, remarked, “even Janis on an off-night was incredible,” acknowledging her struggles but affirming her talent’s enduring power.

Paradoxically, Joplin was deeply dissatisfied with her Woodstock performance. So strong was her self-critique that she insisted her singing not be included in the 1970 documentary film or original soundtrack. This highlights her unwavering perfectionism, though “Work Me, Lord” was later added to the 25th-anniversary director’s cut.

The period following Woodstock continued to reveal her struggles. In November 1969, she was arrested in Tampa, Florida, and fined $200 for “vulgar and indecent language” toward police. Biographer Myra Friedman also described a Madison Square Garden duet where Joplin appeared “so drunk, so stoned, so out of control, that she could have been an institutionalized psychotic rent by mania,” painting a vivid picture of her ongoing battles.

8. **Attempts at Sobriety and Brazilian Interlude (January-July 1970 – Part 1)**Following the intense pressures and public scrutiny that accompanied her Kozmic Blues Band era and the Woodstock performance, Janis Joplin made a significant attempt to recalibrate her life. In February 1970, she traveled to Brazil, a journey meant to offer a respite from the demanding music scene and her escalating battles with addiction. Accompanied by her friend Linda Gravenites, who had designed Joplin’s iconic stage costumes for years, this trip marked a period of deliberate detox, during which Joplin successfully ceased her drug and alcohol use, seeking a much-needed break from her demons.

While in Brazil, a new romance blossomed with David (George) Niehaus, a fellow American tourist on a global journey. Niehaus, notably, was not involved with drugs, a characteristic that Amburn highlighted as one of his most appealing qualities to Joplin during this period of attempted sobriety. Press photographers captured images of Joplin and Niehaus together at the vibrant Rio Carnival in Rio de Janeiro, with Gravenites also documenting their time in color photographs.

These snapshots, as biographer Ellis Amburn described, presented a picture of a “carefree, happy, healthy young couple having a tremendously good time.” This image starkly contrasted with the emaciated and struggling artist seen just months prior. Joplin, herself, shared her renewed sense of freedom during an international phone call interview with *Rolling Stone*, exclaiming, “I’m going into the jungle with a big bear of a beatnik named David Niehaus. I finally remembered I don’t have to be on stage twelve months a year. I’ve decided to go and dig some other jungles for a couple of weeks.” This period, though tragically brief, represented a genuine effort by Joplin to find a path toward health and happiness away from the music industry’s relentless grind.

9. **Relapse and the Formation of Full Tilt Boogie Band (January-July 1970 – Part 2)**The fragile stability Janis Joplin found in Brazil, however, proved tragically short-lived upon her return to the United States. Almost immediately, she resumed her heroin use, signaling a heartbreaking relapse that would quickly unravel the progress she had made. Her relationship with David Niehaus, which had offered such promise during their Brazilian idyll, rapidly deteriorated and ended after he witnessed her injecting drugs at her new home in Larkspur, California. The complexity of her personal life was further exacerbated by her ongoing romantic involvement with Peggy Caserta, who was also an intravenous drug user, creating a toxic feedback loop that was difficult to escape.

Despite these personal setbacks, Joplin’s artistic drive remained potent. Prior to embarking on a summer tour with a newly formed band, she made final, poignant appearances with Big Brother and the Holding Company in a reunion at the Fillmore West and Winterland in San Francisco in April 1970. Recordings from the Fillmore concert would later be released posthumously on *Joplin in Concert*. Reports from these performances indicated that both Joplin and Big Brother were in excellent form, underscoring her enduring vocal power even as her personal struggles continued.

It was during this critical juncture that Joplin assembled her next backing group, initially known as Main Squeeze, before being renamed the Full Tilt Boogie Band. This new ensemble featured a lineup of mostly young Canadian musicians, many of whom had previously worked with Ronnie Hawkins, and included an organ but notably, no horn section. Joplin took a far more hands-on and active role in forming the Full Tilt Boogie Band compared to her previous groups, a testament to her desire for creative control and a cohesive musical unit.

She famously declared, “It’s my band. Finally it’s my band!” This statement reflected a deep sense of ownership and optimism for the musical direction she was forging. After an initial performance under the Main Squeeze moniker at a Hells Angels event in San Rafael in May 1970, the newly named Full Tilt Boogie Band commenced a nationwide tour. Joplin quickly found immense satisfaction with this group, and their performances garnered mostly positive feedback from both her devoted fans and discerning critics, affirming her artistic vision even as her personal battle with addiction raged on, with her drinking notably increasing despite claims of being drug-free.

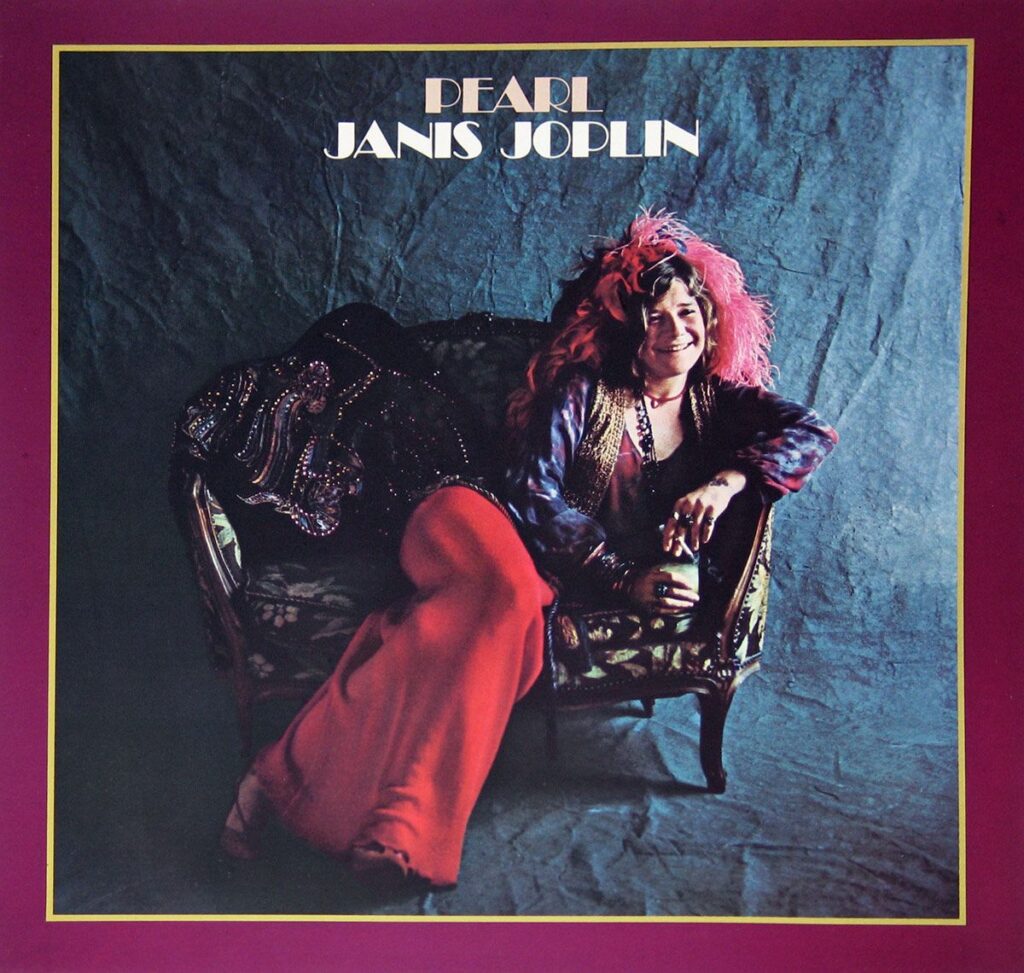

10. **”Pearl” Recording Sessions Begin: A Creative Burst Amidst Personal Turmoil (July-October 1970 – Part 1)**

The summer of 1970 marked the genesis of what would become Janis Joplin’s definitive, and tragically final, artistic statement: the album *Pearl*. On August 24, 1970, Joplin checked into the Landmark Motor Hotel in Hollywood, strategically located near Sunset Sound Recorders, the studio where she would immerse herself in the creation of her new masterpiece. This period saw her dive deep into rehearsals and recording sessions, channeling her raw talent and emotional depth into every track, working intently with producer Paul A. Rothchild, renowned for his collaborations with The Doors.

During these demanding sessions, Joplin’s personal life remained a whirlwind of intense emotions. She continued a relationship with Seth Morgan, a 21-year-old UC Berkeley student, known also as a cocaine dealer and who would later become a novelist. Morgan had been visiting her at her new home in Larkspur in the months prior, and their connection intensified during the *Pearl* recordings. Their relationship culminated in an engagement in early September, just weeks before her death, though Morgan’s presence at the studio sessions was notably infrequent, attending only eight of Joplin’s many rehearsals and recording dates.

The creative atmosphere, however, was palpable. Despite the personal chaos, Joplin’s focus on the music was unwavering. The opening track of what would become *Pearl*, “Move Over,” was penned by Joplin herself, a powerful testament to her feelings about how men often treated women in relationships. This self-penned song served as a bold and assertive introduction to an album that promised to showcase a more mature, yet equally impassioned, side of her artistry. The intensity of these recording sessions, a race against an unseen clock, yielded enough usable material to compile an LP that would posthumously become the biggest-selling album of her career.

11. **The Festival Express and High School Reunion: Public Persona vs. Private Pain (July-October 1970 – Part 2)**

Concurrent with the burgeoning *Pearl* sessions, Joplin and the Full Tilt Boogie Band embarked on the legendary Festival Express tour from June 28 to July 4, 1970. This iconic cross-Canada train journey saw them perform alongside a constellation of rock giants including Buddy Guy, The Band, the Grateful Dead, and Ten Years After, playing electrifying concerts in Toronto, Winnipeg, and Calgary. Footage of her dynamic performance of “Tell Mama” in Calgary would later become a staple MTV video in the early 1980s, solidifying her status as a formidable live act even in her final months.

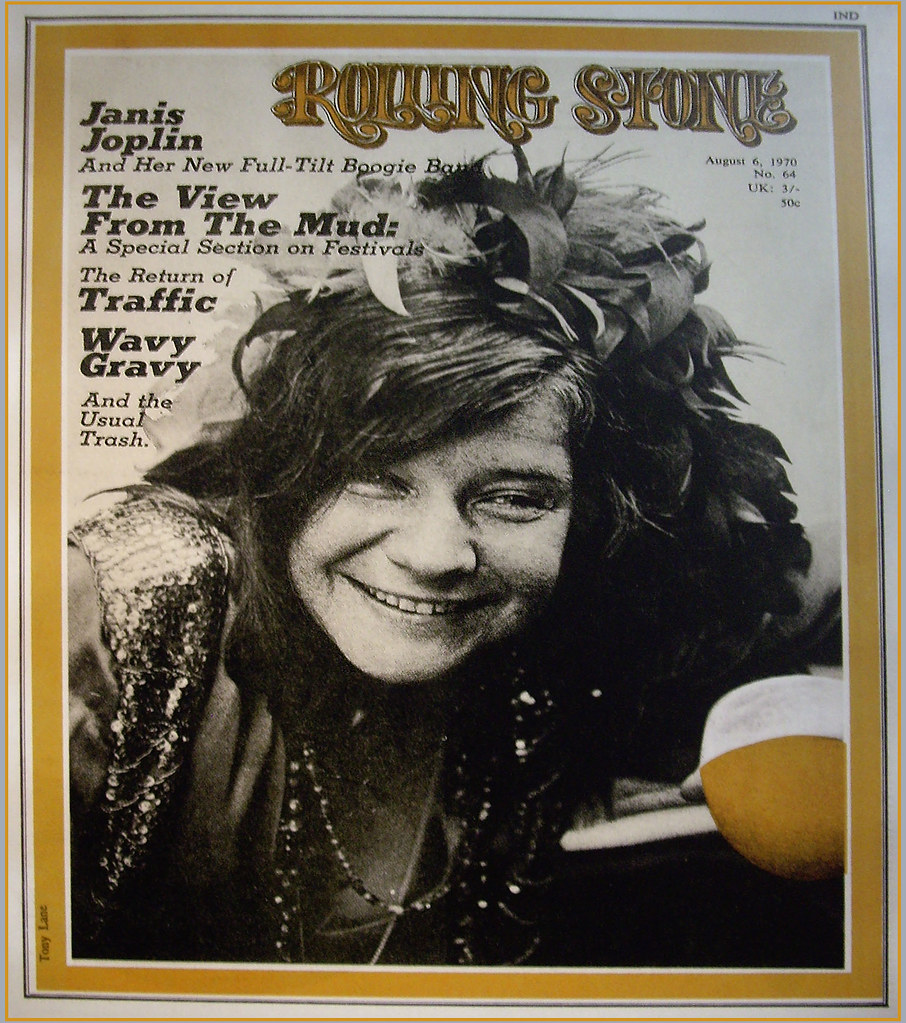

Joplin’s public appearances during this time also offered glimpses into her complex persona. She made two memorable broadcasts on *The Dick Cavett Show*. During her June 25, 1970, appearance, she famously announced her intention to attend her ten-year high school class reunion. When Cavett inquired about her popularity in school, Joplin candidly admitted that her schoolmates had “laughed me out of class, out of town and out of the state,” revealing the deep-seated pain that still lingered from her youth despite her international fame.

This sentiment became even more acutely evident when she actually attended her high school reunion on August 14. Accompanied by Bob Neuwirth, road manager John Byrne Cooke, and her sister Laura, the event, by all accounts, was an unhappy and emotionally charged experience for Joplin. Instead of finding reconciliation or comfort, she openly denigrated Port Arthur and the very classmates who had subjected her to humiliation a decade earlier. It was a stark illustration of how, even at the peak of her success, the wounds of her past continued to shape her present, creating a poignant contrast between her celebrated public image and her enduring private pain.

12. **The Unmarked Grave of Bessie Smith and “Mercedes Benz”: Tributes and Final Recordings (July-October 1970 – Part 3)**

Amidst the intense recording schedule for *Pearl* and her public engagements, Janis Joplin took a significant step to honor one of her most profound musical influences. On August 7, 1970, a tombstone was finally erected at the previously unmarked grave of Bessie Smith, the legendary “Empress of the Blues.” This gesture was jointly funded by Joplin and Juanita Green, a registered nurse who, as a child, had done housework for Smith. Joplin had frequently cited Bessie Smith as a pivotal musical influence, and this act served as a deeply personal tribute from one blues queen to another, recognizing a legacy that had long gone unacknowledged.

It was also during this period that Joplin, with fellow musician and friend Bob Neuwirth, composed what would become one of her most beloved and enduring original songs: “Mercedes Benz.” The song, partially inspired by a poem from Michael McClure, captured a wry commentary on consumerism and spiritual longing. The genesis of this iconic track is steeped in legend, beginning between two shows at the Capitol Theatre. According to publicist Myra Friedman, actors Geraldine Page and her husband Rip Torn attended the first show.

Following the first performance, Joplin, Neuwirth, Page, and Torn retreated to a nearby “gin mill” called Vahsen’s in Port Chester. Neuwirth recounted the scene to *The Wall Street Journal* in 2015, explaining that Joplin came up with the words for the first verse while he jotted them down on bar napkins. She then developed the second verse, centered on a color TV, with Neuwirth suggesting phrases and ultimately crafting the third verse, which humorously asks the Lord to provide a night on the town and another round. This spontaneous burst of creativity led to an immediate performance of the song by Joplin at her second show that very evening.

“Mercedes Benz” became Joplin’s last completed recording, captured in a single, remarkable take on October 1, 1970, just three days before her passing. Its raw, acapella delivery and poignant, yet humorous, lyrics perfectly encapsulated her spirit and served as a powerful, final artistic statement, a testament to her ability to infuse even simple observations with profound meaning.

13. **The Final Days: Escalating Drug Use and Unfinished Business (September-October 1970)**The final weeks of Janis Joplin’s life were marked by a tragic acceleration of her drug use, a stark contrast to her brief period of sobriety in Brazil. Peggy Caserta, in her 1973 book *Going Down With Janis*, claimed that she and Joplin had mutually decided in April 1970 to distance themselves to avoid enabling each other’s addictions. However, by September, Caserta, now smuggling cannabis, had checked into the Landmark Motor Hotel herself, drawn by its reputation as a haven for drug users. Joplin, also staying at the Landmark for the *Pearl* sessions, learned of Caserta’s presence from a shared heroin dealer.

Joplin, desperately seeking heroin, reportedly begged Caserta for a supply. When Caserta refused, Joplin’s chilling response was, “Don’t think if you can get it, I can’t get it.” This defiant statement underscored her deep-seated addiction and her determination to obtain the drug by any means. Within a few days, Joplin became a regular customer of the same heroin dealer who had been supplying Caserta, indicating a rapid escalation of her dependency. Publicist Myra Friedman, who had staged an intervention with Joplin the previous winter, remained tragically unaware of Caserta’s presence in California or this critical encounter until after Joplin’s death.

Despite the escalating personal turmoil, Joplin’s commitment to her art remained, at times, fiercely present. On September 26, 1970, she recorded vocals for “Half Moon” and “Cry Baby.” The session concluded on a lighter note with Joplin, organist Ken Pearson, and drummer Clark Pierson making a special one-minute recording of Dale Evans’ “Happy Trails” as a birthday greeting for John Lennon, a poignant moment of levity amidst the gathering storm of her addiction. The following day, September 27, was Janis’s last day in the studio.

However, the dark clouds of her personal life continued to loom. On Saturday, October 3, Joplin visited Sunset Sound Recorders to listen to the instrumental track for Nick Gravenites’s “Buried Alive in the Blues,” intending to record the vocal the following day. That same Saturday, she discovered that her fiancé, Seth Morgan, had invited other women to her home after meeting them at a Marin County restaurant. Overheard at the studio, Joplin expressed both anger over Morgan’s infidelity and joy about the successful progress of the recording sessions, illustrating the profound emotional highs and lows she was experiencing.

Later that evening, Joplin and Ken Pearson left the studio together, with Joplin driving him in her Porsche to Barney’s Beanery in West Hollywood, where they met Bennett Glotzer, a business partner of her manager Albert Grossman. After midnight, she drove Pearson and a male fan to the Landmark Motor Hotel. During the ride, the fan repeatedly probed her about her singing style, to which she mostly ignored him. As they prepared to part in the Landmark lobby, Joplin, perhaps in jest but with a chilling undertone, expressed a fear that Pearson and the other Full Tilt Boogie musicians might decide to stop making music with her. They then separated, retreating to their respective rooms, unknowingly marking the final hours of her life.

14. **The Tragic End: Overdose at the Landmark Motor Hotel (October 4, 1970)**On the evening of Sunday, October 4, 1970, the vibrant light of Janis Joplin, the “Pearl” of rock and roll, was tragically extinguished. Her road manager and close friend, John Byrne Cooke, discovered her lifeless body on the floor of her room at the Landmark Motor Hotel. Initial newspaper reports indicated the presence of alcohol in the room but no other drugs or paraphernalia, a detail that would later be challenged by official accounts and subsequent investigations, highlighting the immediate complexities surrounding her death.

According to a 1983 book co-authored by Joseph DiMona and Los Angeles County coroner Thomas Noguchi, evidence of narcotics was initially removed from the scene by a friend of Joplin’s. This individual, in a misguided attempt to protect Joplin’s reputation, later returned the evidence after realizing that an autopsy would inevitably reveal the presence of narcotics in her system. Dr. Noguchi, who performed the autopsy, definitively determined the cause of death to be a heroin overdose, potentially compounded by alcohol. This official finding cast a somber shadow over the accidental nature of her passing, confirming the tragic culmination of her long-standing battle with addiction.

John Byrne Cooke, intimately familiar with Joplin’s struggles and her supply, advanced a compelling theory that Joplin had unknowingly obtained heroin significantly more potent than what she and other Los Angeles users typically encountered. This belief was tragically substantiated by a rash of other overdoses among her dealer’s clientele during that same weekend, suggesting a batch of unusually strong heroin was in circulation. Despite the profound grief and speculation, Joplin’s death was officially ruled accidental, emphasizing the unforeseen and unintended consequence of her substance use.

The preceding days were marked by disappointment for Joplin. Both Peggy Caserta, her close friend, and Seth Morgan, her fiancé, had failed to meet her as planned on Friday, October 2. Caserta later noted that Joplin was deeply saddened by her friends’ absence, having eagerly anticipated their company that night. This sense of abandonment, coupled with her escalating drug use and the relentless pressures of her career, created a vortex that she, ultimately, could not escape. Janis Joplin’s legacy, though cut short at the age of 27, continues to reverberate, a powerful testament to her unparalleled talent and the heartbreaking vulnerability that defined her extraordinary life.

In the grand tapestry of rock history, Janis Joplin remains a singular, incandescent figure. Her voice, a raw, blistering force of nature, continues to inspire generations, transcending time and genre. Yet, her story is also a poignant reminder of the fierce internal battles that can rage beneath the surface of even the brightest stars. The circumstances of her passing, a stark, sudden end to a life lived with unbridled passion and profound vulnerability, serve not as a diminishing footnote, but as an integral part of her enduring myth. Janis, the “Pearl,” burned so brightly that she could not but consume herself, leaving behind an inferno of music that echoes with eternal fire.