In the fast-paced world of global economics, few terms ignite as much debate and misunderstanding as ‘foreign imports.’ Often, the popular narrative paints a picture of imports as a detriment, a flood of goods that supposedly siphons away domestic production and jobs. However, much like judging a high-performance vehicle solely by its fuel consumption without acknowledging its engineering marvels, this perspective misses the profound and often beneficial complexities at play. It’s time to shift gears and examine these economic forces with the analytical rigor they deserve.

At MotorTrend, we pride ourselves on dissecting the intricate mechanics of automotive performance, unearthing the subtle engineering choices that define true excellence. We believe the same discerning approach is crucial when evaluating the mechanics of our global economy. Beneath the surface of trade statistics lie powerful economic engines and intricate systems that, when properly understood, reveal a landscape of prosperity and opportunity often obscured by oversimplified rhetoric. It’s not just about what comes in, but what it enables within our borders.

This article aims to dismantle these common misconceptions, providing an expert-driven evaluation of how international trade, particularly the inflow of goods and services, contributes positively to the American economy, its job market, and even its strategic positioning. We’ll explore specific instances where conventional wisdom falls short, revealing the sophisticated, often surprising, ways these so-called ‘foreign imports’ are, in fact, integral to our economic strength and future. Let’s take a closer look at the mechanisms that truly drive our prosperity.

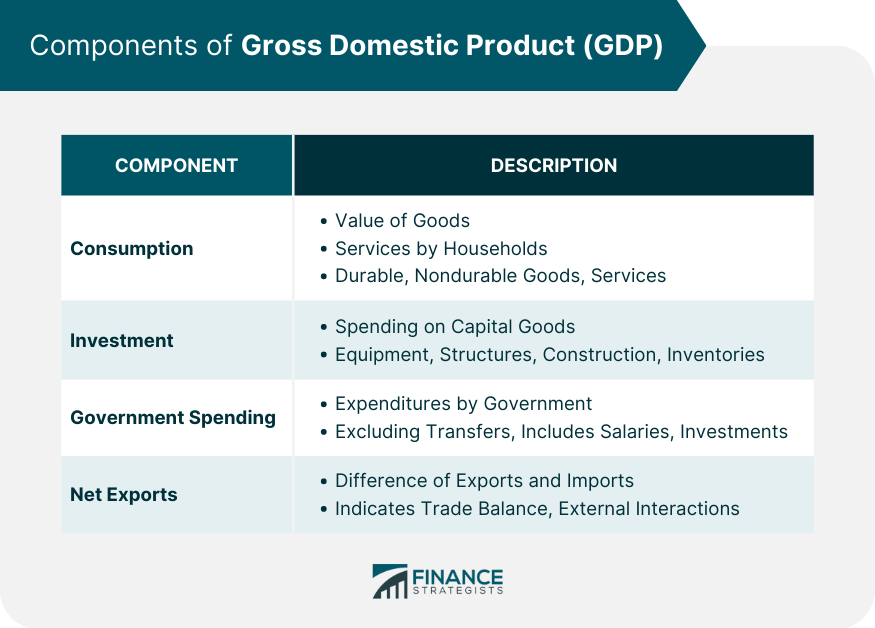

1. The Misunderstood Role of Imports in GDP Calculation

One of the most persistent myths in economic discourse is the idea that imports inherently detract from a nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This belief often stems from a superficial understanding of how GDP is actually calculated, leading to a significant misconception about the economic impact of foreign goods. Experts clarify that “Because GDP estimates the value of production in the U.S., imports are neither added nor subtracted conceptually.” This fundamental principle often gets lost in translation.

Historically, economic statisticians faced a challenge: while they needed to estimate spending, which naturally included expenditures on both domestically produced and imported goods, their ultimate goal was to measure *domestic production*. To accurately achieve this, they had to isolate spending on domestically produced items. The most straightforward solution became to add total consumer, investment, and government spending (which included imports) and then “subtract total imports.” This was a pragmatic accounting method, not an economic indictment of imports.

This subtraction is merely an adjustment to avoid overstating domestic production by counting spending on foreign-made goods. It’s a technical maneuver designed for accuracy in measuring what’s produced *within* the country’s borders, not an indication that imports are harmful. Everyone involved in economic measurement agrees that imports should not be counted in measuring domestic production; the subtraction simply backs out expenditures that were already included in broader spending categories.

Therefore, while the calculation method can cause confusion, the underlying economic reality is that imports do not conceptually reduce GDP. They are simply outside the scope of *domestic* production. Understanding this distinction is crucial to appreciating the true, non-detrimental role imports play in our economy.

2. Imports as a Catalyst for Domestic Job Growth

The narrative that imports are a primary cause of job losses in the United States is deeply entrenched, yet it significantly overlooks the substantial number of domestic jobs that are directly or indirectly created by international trade. This might seem counterintuitive to those who focus solely on manufacturing displacement, but the reality is far more complex and encouraging.

Indeed, “imports create myriad jobs here. Numerous domestic industries rely on them!” These aren’t just a few isolated positions; they represent a broad spectrum of employment across various sectors. From logistics and transportation to warehousing, sales, marketing, and administration, a vast ecosystem of jobs is dedicated to handling, distributing, and selling imported goods within the US.

Consider the intricate global supply chains that bring products to American consumers and businesses. Each step, from port operations to retail shelves, generates domestic employment. Port workers unload cargo, truck drivers transport it, warehouse staff manage inventory, and countless individuals in wholesale and retail ensure these products reach their final destination. These roles are integral to the functioning of our modern economy.

Therefore, to view imports solely as a job destroyer is to miss the extensive economic activity and employment opportunities they stimulate and sustain within the United States. They are a fundamental, job-generating component of a highly integrated global economy, far from being an unalloyed negative.

Read more about: Navigating the Crossroads: Key Legal and Policy Shifts Redefining the Trucking Industry in 2025

3. Fueling US Manufacturing with Essential Imports

The strength and sophistication of American manufacturing are often celebrated, but what’s less commonly acknowledged is its significant reliance on “foreign imports” – not as finished goods, but as crucial raw materials and intermediate components. This reliance is not a weakness, but a strategic advantage that underpins our industrial capacity.

The context explicitly states, “Heck, most American manufacturing uses imported components or raw materials—things like metallic abrasives, steel, sand and gravel from places like Canada, Mexico and Brazil.” In today’s highly specialized global economy, it is simply impractical, and often inefficient, for any single country to produce every single input required for its advanced manufacturing processes from start to finish.

This global sourcing allows US manufacturers to access the highest quality materials, specialized components, or more cost-effective inputs, enabling them to focus on innovation, design, and assembly of higher-value products. By leveraging international supply chains, American companies can remain competitive on a global stage, producing sophisticated goods that would be far more expensive, or even impossible, to make entirely with domestic resources.

Ultimately, the more advanced a country’s manufacturing sector becomes, the more it often depends on a diverse array of imported inputs. These are not competing products, but essential building blocks that empower American industry, making these “foreign imports” a silent but vital contributor to our manufacturing prowess.

Read more about: Navigating the Crossroads: Key Legal and Policy Shifts Redefining the Trucking Industry in 2025

4. The Hidden Job Market: Servicing and Selling Imported Goods

Beyond the direct manufacturing or initial logistics, foreign imports also cultivate a significant and often underestimated segment of the American job market: the vast network of professionals engaged in selling, maintaining, and servicing these products. This constitutes a robust domestic employment sector, intricately linked to the flow of goods from abroad.

The evidence for this is clear and observable. Consider the example provided: “auto dealerships and repair shops that specialize in European, Japanese or Korean cars.” These businesses employ thousands of sales associates, mechanics, parts specialists, and administrative staff across the country. Their livelihoods are directly tied to the availability and popularity of imported vehicles.

But the impact extends far beyond the automotive sector. Think about “washing machine service techs, TV repair people, clothing retailers, the specialists that maintain complex industrial machinery, or, or, or.” Every imported appliance, electronic device, piece of apparel, or specialized industrial tool requires a domestic infrastructure for sales, support, and repair. These jobs are skilled, often well-paying, and contribute significantly to local economies.

Thus, the economic footprint of imported goods is far more expansive than commonly perceived. They create a powerful ripple effect, generating enduring employment opportunities that support a diverse and skilled workforce, long after the products have cleared customs and entered the domestic market.

5. Trade Deficits: A Gateway to Foreign Investment Surpluses

For many, a trade deficit is an immediate cause for concern, often portrayed as money flowing out of the country with no return. However, this view overlooks a critical economic phenomenon: trade deficits frequently translate into foreign investment surpluses, bringing significant capital and opportunity back to the United States.

The mechanism is straightforward yet often misunderstood. When foreign companies sell goods to the U.S., they receive American dollars. A substantial portion of these dollars isn’t immediately converted and repatriated; instead, “many invest those dollars here instead of converting them to their home currency and repatriating them.” This inflow of foreign capital is a powerful economic engine.

These investments are not merely passive holdings like “parking cash in Treasury bonds and/or real estate trophies.” Instead, they are often directed towards initiatives that “add to the real economy—factories, stores, infrastructure, research and development.” Such investments fuel innovation, expand productive capacity, and significantly contribute to job creation and economic growth within the US.

Therefore, the seemingly negative trade deficit is often accompanied by the highly positive phenomenon of foreign direct investment. The dollars that leave the country to pay for imports frequently return as productive capital, making the trade deficit a more complex and often beneficial economic dynamic than popular rhetoric suggests.

6. Imports as a Barometer of Robust Domestic Demand

Counter to the popular belief that rising imports indicate a struggling domestic economy, a robust and expanding flow of imported goods can often serve as a strong indicator of a healthy and confident domestic market. This dynamic is akin to a high-performance engine demonstrating its power through increased fuel consumption—it’s a sign of activity, not weakness.

Economic data consistently supports this view. The trade deficit, largely influenced by import volumes, “typically narrows during recessions—like in 2001 and 2009.” This is because economic downturns lead to reduced consumer and business spending across the board, including on foreign goods. Conversely, “the deficit usually widens or stays flat during expansionary periods, as consumption and investment grow.”

The underlying logic is clear: when consumers feel financially secure and businesses anticipate growth, they increase their spending and investment. This heightened domestic demand often outpaces immediate domestic supply, leading to a natural surge in imports. These imports fulfill consumer desires for variety and competitive pricing, and meet business needs for essential components and capital goods, thereby supporting overall economic expansion.

Consequently, a growing trade deficit, especially when accompanied by strong GDP growth and employment figures, should be viewed not as an economic vulnerability but as a positive “foreign import” signal. It indicates a vibrant economy with strong purchasing power, healthy investment, and the confidence to engage globally.

Read more about: Navigating the Headwinds: 13 Persistent Factors Driving Inflation and Shaping the 2025 Economic Landscape

7. “Total Trade”: A More Accurate Economic Pulse than the Deficit

While the trade deficit frequently dominates headlines and political discourse, focusing solely on this single metric provides an incomplete and often misleading picture of a nation’s cross-border economic activity. A more comprehensive and accurate indicator for assessing global economic engagement is “total trade”—the combined value of both exports and imports.

This holistic metric offers a clearer lens through which to understand economic health because, as experts point out, “imports and exports roughly signal domestic and foreign demand, respectively.” By examining both sides of the ledger, we gain insight into how well economies, both at home and abroad, are performing and interacting, allowing for a much more nuanced evaluation than the deficit alone.

Consider the period of the 2007-2009 global financial crisis. The US economy plunged into a sharp recession, and while the trade deficit might have narrowed, “Total trade tumbled, with imports falling from Q3 2008 through Q1 2009.” A shrinking deficit in this context wasn’t a positive sign of economic improvement; rather, it signaled a severe contraction in demand. The total trade figure accurately reflected the widespread economic distress.

The contrast is even starker during recovery periods. For instance, from “April 2020 – March 2022,” as America’s economy rebounded vigorously from pandemic-era lockdowns, “the US trade deficit nearly doubled.” Yet, framing this solely as a negative misses the crucial context that “Total trade over this span rose 68.3%.” This powerful surge in total trade delivered a far more accurate reflection of rapid economic recovery and resurgent demand, demonstrating that the often-maligned import figure, when viewed as part of total trade, can be a clear indicator of a strong and dynamic economy.

8. The Strategic Imperative of Comparative Advantage

Having peeled back the layers of common misconceptions surrounding imports, it’s crucial to delve into the sophisticated economic principle that often underpins their enduring value: comparative advantage. This concept highlights how nations can maximize efficiency and output by specializing in producing what they do best and trading for what others produce more efficiently. It’s a powerful driver of global prosperity, fostering a world where economic strengths are leveraged for collective benefit.

Consider a prime example from the energy sector. The United States stands as the world’s top oil producer, a fact that might lead one to believe it has no need for imported oil. However, the reality is far more nuanced, driven by specialized industrial infrastructure. As the context explicitly notes, “the US imports tons of oil—despite being the world’s top producer—because US refineries aren’t equipped to process the light, sweet crude America’s vast shale reserves deliver. US refineries are set up primarily for heavy crude.”

This isn’t an inefficiency; it’s a strategic optimization. Instead of undertaking the “enormous cost to businesses” of retooling refineries for light, sweet crude, America exports its domestically abundant lighter crude to countries equipped to process it. Simultaneously, it imports heavier crude, often from neighbors like Canada, that its existing refineries are perfectly designed to handle. This intricate dance of imports and exports ensures that specialized infrastructure is utilized efficiently, benefiting both producers and consumers.

Such a system allows all parties to “win” by focusing on their unique strengths and capabilities. It underscores that trade is not just about what a country can produce, but what it can produce most effectively in relation to others, leading to a global supply chain where specialized inputs become vital “foreign imports” that enhance overall economic performance and competitiveness.

Read more about: Are Annuities a Scam? A Deep Dive into Guaranteed Retirement Income and What Financial Advisors Won’t Tell You

9. Unpacking the Complexities of Tariffs: A Double-Edged Sword

While trade deficits often capture headlines, the policy tools designed to address them, particularly tariffs, present their own intricate challenges. The immediate appeal of tariffs—reducing imports by making them more expensive—can be alluring, yet their broader economic consequences are rarely straightforward. Just as a performance tuner must understand an engine’s entire system, so too must policymakers grasp the full interplay of economic forces when implementing trade barriers.

Economist Obstfeld clarifies that the effect of increased tariffs is far from clear-cut. While they are indeed designed to “reduce imports,” this action often triggers a ripple effect across the global economy. Crucially, tariffs “also will reduce U.S. exports as other countries retaliate and as a stronger dollar (a consequence of fewer imports) makes U.S. goods and services more expensive abroad.” This means a policy aimed at boosting domestic production can inadvertently hurt American exporters by making their products less competitive internationally.

The complications don’t stop there. Many tariffs are imposed not on finished consumer goods, but on “intermediate goods used by U.S. manufacturers to produce final products.” When this occurs, these tariffs act as a hidden tax, increasing the cost of production for American businesses. This tax burdens “both U.S. exports of the final products and U.S. products that compete against imports,” undermining the very industries tariffs are often intended to protect. It’s a critical detail that highlights the interconnectedness of modern supply chains.

Furthermore, if tariffs fail to shrink the trade deficit, Obstfeld warns of potential “political pressure on the Federal Reserve to weaken the dollar by cutting U.S. interest rates.” Such a move, unless the economy is in recession, could prove highly inflationary. He cautions that aggressive tariff and other threats aimed at pressuring foreign partners to strengthen their currencies could “induce economic and political decoupling from the United States as policy compliance,” a far more damaging outcome than a mere trade imbalance.

10. The Budget Deficit’s Unseen Influence on Trade Imbalances

Beyond the direct mechanics of tariffs, a deeper, often overlooked domestic factor significantly influences a nation’s trade balance: its fiscal policy. While it might seem counterintuitive, the size of a country’s budget deficit can have a profound impact on its demand for imports and its reliance on foreign capital. This connection reveals that solutions to trade imbalances might lie as much in domestic financial discipline as in external trade policy.

Economist Obstfeld strongly argues that a more effective way to address the trade deficit, and to lessen “the United States’ need to borrow from foreigners,” is to “decrease the U.S. budget deficit.” When a government spends more than it collects in taxes, it must borrow to cover the difference. This borrowing often draws in foreign capital, which in turn can lead to a stronger domestic currency and greater purchasing power for imports, widening the trade deficit.

As Obstfeld bluntly states, “If Congress passes a budget that raises [fiscal] deficits, the situation is just going to get worse, notwithstanding any tariffs.” This highlights that tariffs, while generating some revenue, are typically insufficient to offset the financial impact of a large budget deficit. The structural demand created by government overspending pulls in imports and attracts foreign capital, making the trade deficit an intertwined symptom of broader fiscal policies.

Therefore, a fundamental rebalancing of the nation’s books, rather than solely focusing on border measures, could yield more sustainable and less disruptive improvements to the trade balance. It’s a call for a holistic approach, recognizing that internal economic decisions have external trade consequences, much like how an engine’s performance is intrinsically linked to its internal fuel management.

11. Trade as a Lever of Geopolitical Power: Hirschman’s Enduring Insights

Beyond pure economic efficiency, international trade wields a potent, often overlooked, dimension: political power. Economist David Y. Yang, building on the mid-20th-century theories of Albert O. Hirschman, reveals how countries strategically use trade disruptions not just for economic gain, but to assert geopolitical dominance. This perspective transforms trade from a simple exchange of goods into a sophisticated instrument of national influence.

Hirschman’s seminal 1945 work, “National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade,” theorized that trade asymmetries could be exploited. It wasn’t merely about deficits or surpluses; the criticality and replaceability of goods were paramount. As Yang explains, “Halting the flow of crude oil tends to pack a far bigger punch than withholding textile exports.” A nation overly reliant on another for essential, hard-to-source goods becomes vulnerable, exposing it to “unfavorable power dynamics.”

Yang and Liu’s modern research rigorously tests these predictions with compelling real-world examples. They cite China’s actions: imposing trade restrictions on Taiwan after a US Speaker of the House visit, blocking rare earth mineral exports to Japan over a fishing dispute, and banning Norwegian salmon imports for nearly a decade as “punishment for awarding a Nobel Prize to the dissident Liu Xiaobo.” These instances powerfully demonstrate trade’s use as an economic weapon to achieve political ends.

Hirschman viewed this through a “positive lens,” suggesting countries could “fight economic wars to achieve the same goals” rather than military conflict. Yet, the implications are profound for global commerce. The strategic restructuring of trade to prioritize power, rather than just efficiency, signals a shift that can ultimately hurt welfare on both sides, making the global economic landscape far more complex and politically charged.

12. The Evolving Global Balance of Trade Power

David Y. Yang and Ernest Liu’s groundbreaking model not only formalizes Hirschman’s theories but also provides empirical evidence of a dramatic shift in global trade power dynamics. Their findings paint a vivid picture of how economic interdependence is increasingly becoming a tool for geopolitical leverage, particularly highlighting the rising influence of certain nations.

Their model unequivocally shows “China’s trade power rising over the past two decades as it turned key industries into political instruments.” Products like chemical goods, medical instruments, and electrical equipment have emerged as especially potent levers for Beijing. This surge in trade power is notable, exceeding expectations given the size of China’s GDP, and is now greater than that of the United States over China.

Conversely, while the “U.S. was able to exert more absolute power over China through trade disruptions” in the early 2000s, this dynamic has fundamentally changed. Yang notes that U.S. findings were “relatively stable” over their 20-year study, but “things have quickly flipped.” Today, “China now has more trade power over the U.S. and, at the moment, can exert positive power over any other entity in the world.” This signals a critical rebalancing of global economic influence.

The research also offers fascinating insights into regional dynamics. For instance, while the “European Union acted as one country, it would actually be able to exercise positive power over China,” individual EU members, by engaging bilaterally, are weaker. Yang observes that “medium-sized countries are very much the ones that get bullied,” underscoring the vulnerabilities inherent in imbalanced trade relationships. This strategic consideration of trade, prioritizing power over pure efficiency, is a significant shift from the post-WWII era, making trade decisions less about mutual benefit and more about strategic positioning.

Read more about: The Unavoidable $5 Million Annual Spend: Dissecting Kim Kardashian’s Essential Financial Commitments to Her Billion-Dollar Empire

13. Public Opinion and the Politics of Trade: A Shifting American Narrative

In the ever-evolving discourse surrounding international trade, public perception plays a pivotal role, often shaping policy and political rhetoric. Recent polling data reveals a fascinating shift in American attitudes, showcasing a generally positive view of trade, yet marked by distinct partisan divisions, particularly concerning the role of tariffs and the pursuit of economic self-sufficiency.

A Chicago Council on Global Affairs-Ipsos poll from April 2025 indicates that “large majorities of the public view international trade as good for the US economy, job creation, and people like them.” In fact, American views of trade as beneficial for job creation and their standard of living have reached “all-time highs” in decades of Council polling. This broadly positive sentiment reflects a recognition of trade’s tangible benefits, from increased consumer choice to economic growth.

However, beneath this consensus, partisan lines reveal intriguing differences. While a majority of Americans now favor global free trade, up significantly from previous years, “half of Republicans (51%) instead favor reducing international trade and pursuing self-sufficiency.” This perspective often aligns with the belief that tariffs will help American workers and manufacturing, even if it means higher prices. As a March Reuters/Ipsos Survey found, “58 percent of Republicans supporting higher tariffs on foreign goods even if doing so increased prices.”

Despite these differences, there’s a powerful overarching sentiment. According to a Gallup World Affairs poll, “eight in 10 Americans (81%) say foreign trade is more of an opportunity to boost American economic growth through increased exports (81%) than a threat to the economy from foreign imports (14%).” This overwhelming preference for trade as an export opportunity, driven significantly by a rebound in Republican enthusiasm, underscores a national desire to leverage global markets for American-made goods, viewing imports as necessary components within a larger, beneficial trade ecosystem.

14. WTO Insights: AI, Tariffs, and the Future of Global Merchandise Trade

As we navigate the intricate currents of global commerce, understanding the latest forecasts from authoritative bodies like the World Trade Organization (WTO) is essential. Their insights provide a vital ‘dashboard’ for anticipating shifts in international trade, revealing the powerful, often unexpected, forces that are shaping the flow of goods and services worldwide.

The WTO recently delivered a significantly more optimistic outlook for merchandise trade, sharply raising its forecast for 2025 to 2.4% growth, a notable jump from earlier predictions of a decline. This upward revision is largely driven by a confluence of factors that speak to the dynamism of the global economy. Director-General Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala specifically pointed to “robust trade in artificial intelligence-related goods” as a primary catalyst.

Indeed, the surge in demand for semiconductors, servers, and telecommunications equipment, all integral to the AI revolution, accounted for a staggering “42% of global trade growth,” far exceeding their 15% share in world trade. This ‘AI boom’ signifies a major capital investment wave, profoundly impacting manufacturing and supply chains globally. Furthermore, “importers front-loading orders to get ahead of future tariff hikes or retaliation,” particularly in the US, contributed to an unexpected boost in import volumes, leading to record inventory levels.

Complementing these drivers, the WTO also highlighted the resilience of trade due to “measured response to tariff changes in general” and “increased trade among the rest of the world—particularly among emerging economies.” South-South trade, among developing countries, notably grew 8% year-on-year in value terms, indicating new axes of global economic activity. These combined forces paint a picture of a global trade system that, despite facing headwinds, demonstrates remarkable adaptability and growth, driven by technological advancement and evolving geopolitical strategies.

The narrative around foreign imports is far richer and more complex than often portrayed. Far from being a simple drain on the domestic economy, these international exchanges serve as essential engines for growth, innovation, and strategic positioning. They fuel our manufacturing, create diverse job opportunities, and enable our economy to leverage global efficiencies through comparative advantage. As we’ve explored, what might appear as a ‘deficit’ can often be a gateway to vital foreign investment, and even the geopolitical landscape is now inextricably linked to the intricate web of trade flows. The future of global commerce, shaped by technological leaps like AI and the careful navigation of strategic policy, demands an analytical rigor akin to understanding the most finely tuned performance machine. It’s a dynamic, ever-evolving system, one where nuanced understanding is paramount to unlocking sustained prosperity and influence on the world stage.