The world of art and history is a realm of profound beauty, breathtaking skill, and often, astonishing mystery. We are drawn to relics of the past and masterpieces of human creativity, eager to connect with the minds and hands that shaped them. But what happens when that connection is a lie? What if the very artifacts we revere were born not of ancient hands or celebrated geniuses, but from the cunning and skill of master counterfeiters?

It’s a thought that can send shivers down an art historian’s spine, but it’s a reality that has shaped the collections of prestigious museums and the very fabric of historical understanding for centuries. Whether driven by greed, a desire for recognition, or even just a well-intended practical joke, history’s art forgers have fabricated lost pieces, made exacting copies of originals, and imagined whole new visions in the style of famed creators. So extensive are these deceptions that there’s even a Museum of Art Fakes in Vienna, Austria, filled with their duplicitous work.

While we might instinctively argue that a famous art forger is a bad one, the truth is often the opposite. Many of the world’s most famous art forgeries spent many years, even decades, undetected, seamlessly blending into collections and narratives. It’s when these deceptions are finally brought to light that the person behind them often quickly becomes famous themselves. The ethics of forging artworks remain, at best, dubious, but it is hard not to admire the sheer skill involved in successfully pulling the wool over the eyes of so many so-called experts. Let’s embark on a fascinating journey to explore some of the most notorious deceptions that truly shocked the world.

1. **The Faun: A Greenhalgh Family Masterpiece of Deception**

Our first stop brings us to a curious 18.5-inch ceramic sculpture of a faun that, for a decade, was a prized artwork in the esteemed Chicago Art Institute. It was attributed to the renowned French artist Paul Gauguin, a name that evokes images of vibrant, post-Impressionist beauty. However, in 2007, the art world received a stunning revelation: this charming faun was, in fact, just one of many incredibly clever forgeries crafted and sold by the notorious Greenhalgh family from northern England.

This family unit, often cited as one of the most infamous groups of art forgers ever to live, operated with remarkable precision. The son, Shaun, was the artistic genius, meticulously producing the sculptures, while his parents, George and Olive, handled the crucial task of sales. Together, they generated an astounding range of work, not just the physical pieces but also complete with counterfeit documents such as letters and bills of sale, all designed to establish fake but convincing provenance.

Shaun’s brilliance lay in his ability to craft copies of lost objects that could theoretically turn up at an auction or in an attic, filling perceived gaps in art history. For instance, he based his faun ceramic on an 1800s sketch found in Gauguin’s notebook, drawing on this real illustration to assemble something that could realistically exist. Astonishingly, technical analysis of the piece by the museum had found no red flags, a testament to Shaun’s meticulous attention to detail and understanding of historical materials.

Beyond the Gauguin faun, the Greenhalghs’ prolific output included a vast array of forgeries. They attempted to sell the 10th-century Eadred Reliquary to Manchester University, while an ancient Egyptian statue known as the Amarna Princess successfully made its way into the Bolton Museum. Even the prestigious British Museum acquired one of their creations, a Roman silver tray called the Risley Park Lanx, highlighting the sheer breadth of their deceptions across different periods and cultures.

Despite police estimates that the family made around $1.6 million from their illicit artwork, they maintained a surprisingly simple existence, living in public housing within the industrial town of Bolton. Shaun, the artistic mastermind, crafted his faux masterpieces not in a grand studio, but in the humble confines of a garden shed. Their incredible run finally came to an end around 2005 when three Assyrian reliefs they offered to the British Museum raised suspicions. Experts noticed historical inaccuracies, leading the museum to contact Scotland Yard. After nearly two decades of making and selling forgeries, the Greenhalghs were exposed, with Shaun sentenced to four years and eight months in prison, while his elderly parents received suspended or deferred sentences. Even after his release in 2010, Shaun Greenhalgh provocatively claimed that some of his forgeries were still out there, continuing to fool the unsuspecting art world.

2. **Sleeping Eros: Michelangelo’s Audacious Youthful Deception**

It might come as a shock to discover that one of the undisputed giants of the Renaissance, Michelangelo Buonarotti, began his storied career not as a revered master, but as an art forger. Long before he gazed upon the Sistine Chapel ceiling, Michelangelo, at the tender age of 21 in 1496, was struggling to make his way as a famous artist. He found a lucrative path by applying his extraordinary skills to the production of fake Greek and Roman antiquities, highly coveted items among Rome’s wealthiest citizens.

Finding genuine ancient artifacts that had survived more than a millennium was, as one might imagine, far from straightforward. While under the employ of the powerful Medici family, Michelangelo was approached by a rival sculptor for help in creating a statue that appeared as though it had been buried and recently rediscovered. His solution was ingenious: he carved a sleeping cupid figure in marble, later known as Sleeping Eros, and then treated it to convincingly mimic the ancient Roman statues so popular at the time.

The process of aging the sculpture was critical to the deception. By some accounts, it was the art dealer Baldassarre del Milanese who aged the piece, allegedly by burying it in his vineyard, allowing the acidic soil to lend it the patina of antiquity. The ploy worked, and his forged antiquity was successfully sold through del Milanese to the unsuspecting Cardinal Raffaele Riario of San Giorgio.

When Cardinal Riario eventually uncovered the deception, he returned the statue. However, in a surprising turn of events, he chose not to press charges against the clearly talented young artist. Far from harming Michelangelo’s burgeoning reputation, this act of chicanery, in fact, enhanced it. The cardinal, recognizing the sculptor’s immense skill, was so impressed that he commissioned additional works directly from the Florentine master.

The sculpture was so highly appreciated by Michelangelo’s contemporaries, both as an artwork in its own right and as a remarkably successful forgery, that it was reportedly displayed alongside genuine 4th-century ancient Greek statues. It eventually found its way into the collection of King Charles I and was displayed in one of his palaces. Sadly, the Sleeping Eros is now believed to have been damaged beyond repair and ultimately lost in the devastating Whitehall Palace fire of 1698, leaving behind only the fascinating story of its audacious origin.

3. **The Marienkirche Frescoes: A Post-War ‘Miracle’ Painted Anew**

The destruction of World War II left an indelible scar on Europe, and on March 29, 1942, the historic city of Lübeck, Germany, suffered immense bombing. Among the many historic buildings consumed by flames was the Marienkirche church. As the fires raged and plaster peeled off the church’s walls, something extraordinary was revealed: long-forgotten gothic frescoes, hidden for centuries. This stunning find amid such devastation was immediately hailed as “the miracle of Marienkirche” and quickly afforded protection by improvised roofing.

However, by the war’s end, the precious paintings were in an incredibly precarious state. Lothar Malskat, who was assisting restorer Dietrich Fey in the painstaking conservation efforts, later made a shocking confession. He stated that barely any of the original paint survived, and chillingly, “even that turned to dust when I blew on it.” The frescoes were, in essence, lost.

Yet, in 1951, a grand announcement was made: the frescoes were pronounced fully restored, vibrant and spectacular. People celebrated these icons of postwar reconstruction, viewing them as symbols of hope and resilience. Commemorative stamps were even issued to mark their return. Curiously, no one seemed to publicly question the intense vibrancy of the pigments or how so many intricate details could have possibly endured through the brutal bombing and prolonged exposure to the elements.

But about eight months after their triumphant unveiling, Malskat himself, fueled by resentment because Fey had taken all the credit for the restoration, stepped forward with an explosive claim: he had painted them all. He admitted to basing the face of the Virgin Mary on the 1930s Austrian actress Hansi Knoteck, using his own father as one of the prophets, modeling another figure on Rasputin, and even employing a simple brick to distress the portraits, giving them an aged appearance.

Malskat and Fey were subsequently arrested and eventually sentenced to prison time for their elaborate deception. Further investigations revealed other Malskat forgeries, including his takes on celebrated modern artists like Marc Chagall and Matisse, discovered when police searched his house. While some of the Marienkirche frescoes were ultimately plastered over following the scandal, others reportedly remain in the church to this day, a silent testament to a truly audacious artistic fraud.

4. **The Rospigliosi Cup: A Renaissance Masterpiece or 19th-Century Imitation?**

The late 1970s brought a tremor of anxiety through the hallowed halls of the museum world, triggered by research into a cache of a thousand drawings by a 19th-century German goldsmith named Reinhold Vasters. These works had resided at the Victoria and Albert Museum since Vasters’s death in 1909, seemingly unexamined in detail. It was only during a re-examination by curious scholars that a startling observation was made: many of Vasters’s designs bore an uncanny resemblance to works supposedly dating from the Renaissance, including objects proudly displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

The implications were profound. In 1984, the art world was rocked by the report that at least 45 items of the Met’s European jewelry and other objects, once believed to be from the 16th or 17th century, were in fact centuries younger. Among these dramatically re-attributed pieces was the famed Rospigliosi Cup, a magnificent object once confidently attributed to the legendary 16th-century Italian goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini, a master of the Renaissance.

Philippe de Montebello, who was then the director of the Met, gravely informed The New York Times that the scope of this deception was likely far-reaching. He stated, “Most likely every major repository of Renaissance jewelry, metalwork and mounted crystals will find that a disturbing proportion of their holdings date from the 19th and not the 16th or 17th century.” This suggested a systemic issue, a widespread re-evaluation of collections that had long been considered sacrosanct.

Further investigation into this widespread fraud shed light on the likely culprit behind the successful passing off of these modern creations as authentic antiques. Viennese collector Frederic Spitzer, known for his keen interest in Renaissance styles, had commissioned several objects from Vasters. It is now strongly believed that Spitzer was the one who then presented and sold these Vasters creations as genuine historical artifacts, weaving a convincing narrative around them that duped experts and institutions alike.

Today, the Rospigliosi Cup remains on public view at the Met. However, its label now reflects the truth revealed by meticulous scholarship. It is no longer identified as an original Cellini, a genuine Renaissance artifact, but rather as a masterful 19th-century copy, a testament to Reinhold Vasters’s skill and a fascinating chapter in the history of art forgery that reshaped how museums authenticate their collections.

5. **Vase de Fleurs (Lilas): The Dealer Who Duplicated Masterpieces**

Imagine the scene in 2000, when a truly bizarre event unfolded simultaneously at two of the world’s leading auction houses, Christie’s and Sotheby’s. Both prestigious institutions featured the exact same painting in their spring catalogues: Paul Gauguin’s 1885 *Vase de Fleurs (Lilas)*. The immediate and obvious problem was that only one of them could possibly be authentic. They promptly presented both works to a renowned Gauguin expert, who, after careful examination, delivered a verdict that sent shockwaves through the art market: Christie’s had a forgery on its hands.

Curiously, the tangled history of both paintings pointed back to a single individual: the New York-based art dealer Ely Sakhai. As Sakhai would later articulate in his guilty plea, he had devised an audacious and highly lucrative business model. His scheme involved acquiring authentic, but often not widely known, works by famous artists such as Gauguin, Marc Chagall, Amedeo Modigliani, Paul Klee, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. These were the ‘originals’ for his operation.

Then came the crucial step: Sakhai employed talented Chinese immigrant artists to create incredibly detailed copies of these authentic works. These reproductions were not merely good; they were exceptionally meticulous, going so far as to replicate even minute imperfections found on the back of the original canvases. To further bolster their perceived authenticity, these copies were often accompanied by seemingly official certificates of authenticity, carefully fabricated to pass expert scrutiny.

Sakhai’s strategy for avoiding detection was equally calculated. He primarily sold the reproductions in Asia, while the genuine originals were sold in Europe and the United States. His hope was a simple yet ambitious one: that the originals and their meticulously crafted copies would never cross paths, thus keeping his elaborate fraud concealed. For a time, this strategy proved remarkably effective, allowing him to amass a considerable fortune.

However, as with many such deceptions, the inevitable happened: the two versions of *Vase de Fleurs (Lilas)* finally met, leading to the dramatic expose at the auction houses. Sakhai’s sophisticated scheme unravelled, leading to his arrest and subsequent guilty plea. He was sentenced to 41 months in prison and ordered to pay a staggering $12.5 million to the various collectors he had so expertly duped. The tale of Ely Sakhai remains a chilling reminder of how even seemingly foolproof plans for art forgery can ultimately be undone by the very nature of the art world itself.

Welcome back, intrepid explorers of historical deception! Our journey into the cunning world of counterfeiters continues, venturing beyond the canvases and into the very fabric of historical truth. If you thought the last set of forgeries was mind-bending, prepare yourselves, because the ingenuity and sheer audacity behind these next five fabrications are truly astounding. These are the stories where the line between reality and elaborate fiction blurs, challenging our perceptions of authenticity and leaving a lasting mark on history and art alike.

6. **Han van Meegeren’s Vermeers: The Forger Who Fooled Nazis and Experts**

Imagine being charged with treason for selling a national treasure to a Nazi, only to reveal that the treasure itself was a brilliant fake, crafted by your own hand. This was the extraordinary predicament of Dutch artist Han van Meegeren after World War II. When the Allied Art Commission uncovered a previously unknown Vermeer painting in Hermann Göring’s collection, suspicion quickly fell on van Meegeren, the art dealer who had sold it. He faced severe charges for collaborating with the enemy, a fate he desperately wished to avoid.

Van Meegeren found himself in a profound quandary. To escape the treason charge, he would have to confess to a comprehensive history of forgery, a deceit that had earned him millions over several years. This elaborate scheme was born from a struggling career, where critics had dismissed his Rembrandt-style portraits as lacking originality. Driven by a desire for revenge and recognition, he set out to prove he could fool the very establishment that had scorned him.

His first audacious fake, “Christ at Emmaus,” was a masterpiece of deception. Van Meegeren not only used authentic-seeming pigments but also innovated a technique to age the canvas. He added Bakelite, a synthetic resin, to mimic the texture of centuries-old paint, then literally cooked the canvas in a pizza oven to cure it. In 1937, a leading authority on Dutch art proclaimed it “a hitherto unknown painting by a great master… And what a picture!” Van Meegeren’s success wasn’t just about mimicking Vermeer’s style; he masterfully exploited the prevailing art historical belief that Vermeer had a religious period, slotting his new work perfectly into that perceived gap.

His fraudulent success continued, with six more “Vermeers” painted, including “Christ with the Woman Taken in Adultery,” which Göring famously acquired. Van Meegeren splurged on champagne and hotels, stashing his ill-gotten gains in gardens and beneath floorboards. But his intricate web of lies began to unravel when faced with the treason charge. After six weeks in prison, he finally told his captors, “You think I sold a priceless Vermeer to Göring? There was no Vermeer. I painted it myself.” Unbelieved, he famously painted another Vermeer in front of reporters and court-appointed witnesses, proving his extraordinary skill.

Van Meegeren was ultimately sentenced to just one year in prison for forgery, a far lighter sentence than the capital offense of treason. He died before serving his sentence, having been transformed into a Dutch folk hero for famously tricking the Nazis. His story highlights not only the astonishing skill required to create such convincing fakes but also the psychological element of forgery, where the desire to prove oneself can override all ethical considerations.

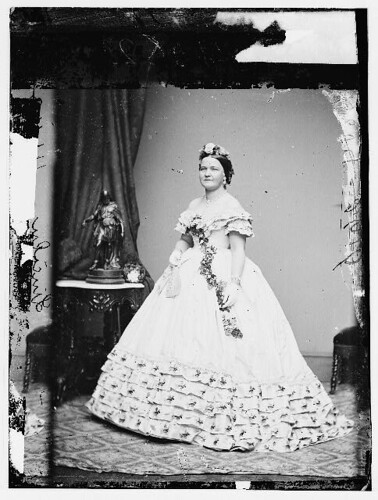

7. **The Mary Todd Lincoln Portrait: A Presidential Impersonation**

For more than three decades, a stately portrait graced the walls of the Illinois governor’s mansion, confidently presented as an authentic depiction of Mary Todd Lincoln. Attributed to the esteemed 19th-century portrait painter Francis Bicknell Carpenter, it came with a poignant and dramatic narrative: a surprise gift for President Abraham Lincoln, commissioned by his wife in 1864, which sadly never reached him due to his assassination. It was a story that added layers of historical significance and emotional depth to the artwork.

However, the truth, as it so often does with forgeries, eventually emerged. Around 2012, an art restorer meticulously examining the painting made a startling discovery: the signature was not original but had been added sometime after the painting was completed. Even more astonishingly, the woman depicted in the portrait was not Mary Todd Lincoln at all, but an anonymous individual whose identity had been obscured by a cunning deception. The historical narrative built around the painting was entirely fabricated.

The New York Times, which had originally reported on the painting’s “discovery” back in 1929, later revealed the mastermind behind this particular con. A man named Ludwig Pflum was identified as the culprit. It is now widely believed that Pflum deliberately altered some of the features of the original painting, including adding a brooch prominently featuring an image of President Lincoln, to create a convincing likeness that he could then sell to Lincoln’s unsuspecting family. This act of familial deception ultimately led to the painting’s journey through various collections, landing it in the state’s historical library in the 1970s before its prominent display in the governor’s mansion.

This forgery serves as a stark reminder that even cherished historical artifacts can be the product of deliberate deceit. The desire to create a tangible link to a celebrated figure, whether for monetary gain or historical embellishment, can lead to the fabrication of objects that mislead generations. It’s a fascinating example of how a compelling story can be as powerful as artistic skill in authenticating a fake.

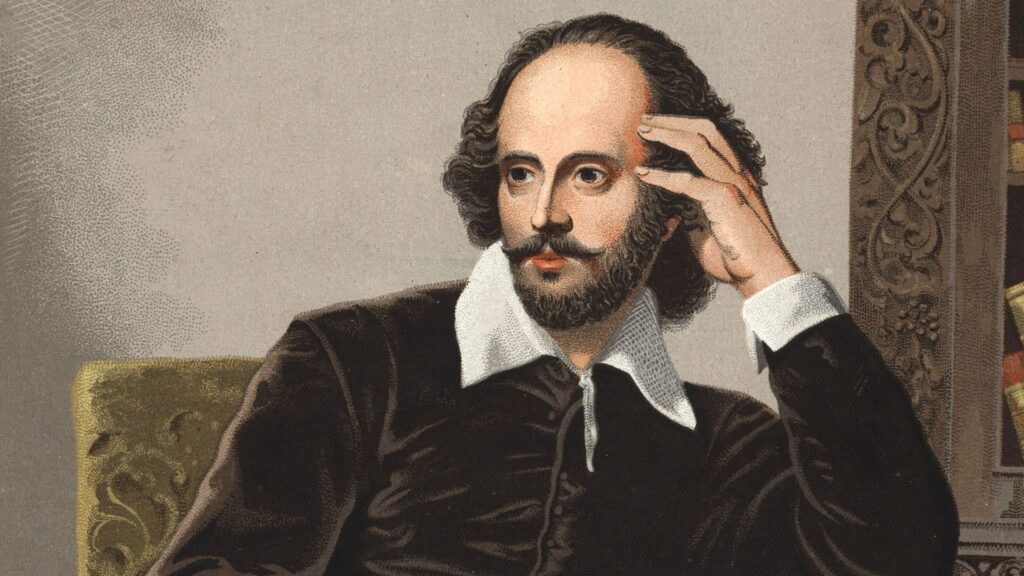

8. **The Flower Portrait of William Shakespeare: An Elizabethan Enigma, Reimagined**

Among the many images purporting to capture the likeness of William Shakespeare, the “Flower Portrait” held a special place for generations. Signed and dated 1609, it was widely considered by many to be a rare depiction of the English playwright created during his actual lifetime, offering a direct window into the Bard’s living appearance. This belief fueled its widespread reproduction on countless books and publications of Shakespeare’s plays for over a century, cementing its place in the public imagination.

However, the painstaking work of art experts at the National Portrait Gallery in London shattered this long-held assumption in 2005. Their meticulous investigation determined that the oil painting on wood panel was not a contemporary of Shakespeare at all, but rather dated only to the early 19th century. This re-attribution fundamentally shifted its status from a rare historical document to a much younger, albeit still intriguing, artistic creation. The Flower Portrait, named after Sir Desmond Flower who gave it to the Royal Shakespeare Company, was now viewed through a different lens.

One of the key pieces of evidence that unmasked the portrait’s true age was a seemingly minor detail: the presence of chrome yellow pigment in the paint. This particular pigment, crucial to its composition, was not invented until the early 1800s, making it impossible for the painting to have been created in 1609. The scientific analysis provided an irrefutable timeline that contradicted the portrait’s purported origin.

Previously, a prevailing theory suggested that the Flower Portrait had actually served as the inspiration for the Droeshout engraving, a posthumous portrait of Shakespeare that accompanied the first folio publication of his work in 1623. With the new findings, this theory was inverted; it is now believed that the Flower Portrait, with its wide-eyed Shakespeare and large white collar, was actually based on the much earlier Droeshout engraving, effectively making it an imaginative interpretation rather than a direct observation of the playwright. The tale of the Flower Portrait underscores how scientific advancements continually refine our understanding of art history, sometimes revealing beloved ‘originals’ to be much later fabrications.

9. **The Drake Plate: A Prank That Rewrote History**

In 1579, the renowned Elizabethan seaman Francis Drake made a pivotal landing on the west coast of North America as part of his circumnavigation of the world. A contemporary account from aboard his ship noted that Drake left behind a brass plate to commemorate the event and formally claim the region, which he named Nova Albion, in the name of Queen Elizabeth of England. For centuries, historians theorized about the exact location of this landing, with many believing it must have been somewhere in California. However, by the early twentieth century, scholarly research began to suggest that Drake had likely landed further north, possibly in the Pacific Northwest.

Enter Herbert Eugene Bolton, a prominent historian and University of California Professor, who was a passionate admirer of Drake and fiercely committed to the idea that the famous seadog had indeed landed in California. His dedication to this belief would soon be met with what seemed like undeniable proof. In 1936, a brass plate was “discovered,” bearing a strikingly authentic-looking inscription: “BEE IT KNOWNE VNTO ALL MEN BY THESE PRESENTS. IVNE. 17. 1579. BY THE GRACE OF GOD AND IN THE NAME OF HERR MAIESTY QVEEN ELIZABETH OF ENGLAND AND HERR SVCCESSORS FOREVER, I TAKE POSSESSION OF THIS KINGDOME WHOSE KING AND PEOPLE FREELY RESIGNE THEIR RIGHT AND TITLE IN THE WHOLE LAND VNTO HERR MAIESTIEES KEEPING. NOW NAMED BY ME AND TO BEE KNOWNE V(N) TO ALL MEN AS NOVA ALBION. G. FRANCIS DRAKE.”

Professor Bolton was reportedly overjoyed, believing that irrefutable evidence of Drake’s California landing had finally surfaced. The discovery of the plate became an instant sensation, captivating the public and historians alike. Copies were produced and sold as souvenirs, photographs appeared in countless textbooks, and it was even presented to Queen Elizabeth II, solidifying its place as a revered historical artifact. The plate was celebrated as a definitive link to a crucial moment in English exploration and American history.

However, as the adage goes, if something seems too good to be true, it often is. Decades later, the shocking truth emerged: the Drake Plate was a sophisticated forgery. It was not a relic from the 16th century but rather an elaborate practical joke that had spiraled wildly out of control. This wasn’t a forgery driven by greed, but rather by the desire to play a clever trick on a Drake enthusiast, which inadvertently fooled the world. The tale of the Drake Plate is a compelling example of how easily historical narratives can be shaped—and misdirected—by expertly crafted fabrications.

10. **Yves Chaudron’s Mona Lisa Fakes: The Phantom Copies**

It takes immense skill to forge an artwork that successfully deceives experts. It takes an entirely different level of audacious genius to forge multiple copies of arguably the most famous painting on Earth, the Mona Lisa, and sell them *before* the original is even stolen. This extraordinary feat is credited to Yves Chaudron, a French painter who played a crucial role in one of art history’s most audacious heists. He was recruited by Eduardo de Valfierno, the mastermind behind the infamous 1911 theft of Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece from the Louvre.

Valfierno’s plan was ingenious and relied heavily on Chaudron’s impeccable skills. Before the actual theft of the Mona Lisa, Chaudron meticulously created several high-quality fakes of the painting. These reproductions were so convincing that they could easily pass for the genuine article. The purpose of these copies was not to replace the original in the museum, but to be sold to wealthy foreign buyers who believed they were acquiring the true masterpiece.

The deception worked flawlessly. Chaudron’s fakes were sold as genuine works even before Vincenzo Peruggia, Valfierno’s accomplice, ever walked out of the Louvre with the real Mona Lisa tucked under his smock. This pre-emptive selling of fakes meant that by the time the theft of the original was discovered and created a global sensation, multiple collectors around the world believed they already possessed it. This clever timing and distribution shielded the forger from immediate suspicion.

Perhaps the most astonishing aspect of Chaudron’s involvement is that he was never actually caught for his part in the crime during his lifetime. His critical role in the scheme was only revealed after his death, ensuring his anonymity while the world scrambled to find the “stolen” original and unknowingly purchased his meticulously crafted counterfeits. Chaudron reportedly forged other paintings as well, though none achieved the mythical status of his Mona Lisa deceptions, making him a true phantom in the annals of art forgery.

And so, we conclude our fascinating journey through the labyrinthine world of forged artifacts and master counterfeiters. From Michelangelo’s youthful prank to van Meegeren’s wartime deceptions, and from seemingly benign historical pranks to sophisticated criminal enterprises, these stories are a testament to human ingenuity—both in creation and deception. They remind us that the allure of authenticity is powerful, and the line between genuine and fake can be astonishingly thin. As technology advances, detection methods become more sophisticated, yet the thrill of the chase, and the sheer audacity of those who dare to dupe the art world, ensures that the history of forgery will always remain a captivating chapter in the story of human creativity.