When we speak of “the world,” what exactly do we mean? This seemingly simple question unravels into a tapestry of profound and complex answers, as thinkers across millennia and disciplines have grappled with defining the totality of existence. From the vast expanse of the cosmos to the intricate workings of the human mind, the concept of “world” has been an intellectual battleground, shaping our understanding of reality itself. It’s a journey into the very fabric of what is, has been, and will be.

The quest to comprehend this overarching reality has led to some truly remarkable intellectual innovations—frameworks and conceptualizations that, in their own right, represent groundbreaking achievements in human thought. These aren’t just dry academic distinctions; they are powerful lenses through which we perceive our place in the grand scheme of things, influencing everything from scientific inquiry to spiritual solace. Each perspective offers a unique “mechanic” for understanding the ultimate system we inhabit.

In this article, we embark on an illuminating exploration of thirteen such pivotal conceptualizations. We’ll delve into how science, philosophy, and religion have meticulously constructed diverse models of “the world,” revealing the sheer depth and ingenuity involved in humanity’s continuous endeavor to map the boundaries and nature of all that exists. Prepare to have your perceptions of reality broadened as we uncover these defining interpretations.

1. **Scientific Cosmology: The Universe as Totality**

In the realm of scientific cosmology, the “world” or “universe” is most commonly defined with an impressive scope: it is understood as “the totality of all space and time; all that is, has been, and will be.” This sweeping definition immediately sets the stage for a grand narrative of existence, encompassing every particle, every moment, and every potentiality within a single, unified framework. It’s a concept that seeks to grasp the entirety of physical reality through empirical observation and theoretical models, striving for a comprehensive understanding of our cosmic home.

Beyond merely space and time, scientific conceptions of the universe also emphasize two other crucial components. These include the various forms of energy and matter, ranging from the colossal stars and galaxies to the most fundamental subatomic particles that underpin all physical structures. Equally vital are the laws of nature—the immutable principles that govern the interactions and behaviors of these physical constituents, dictating everything from gravity to electromagnetism. Together, these elements form the intricate machinery of the cosmos.

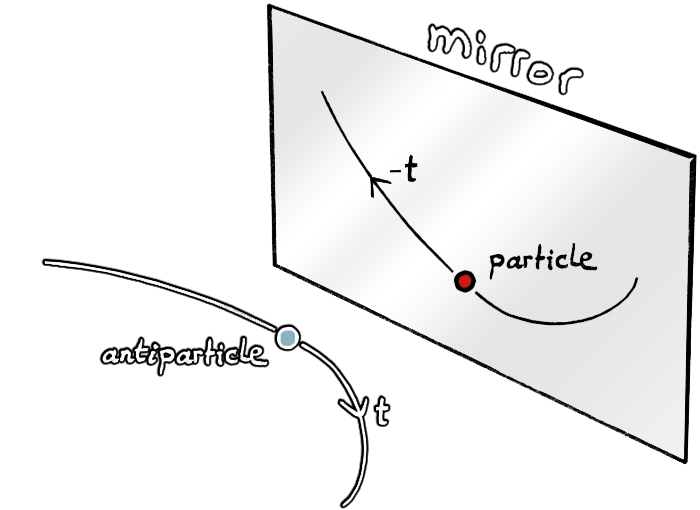

Modern cosmology is deeply influenced by the theory of relativity, which has profoundly reshaped our understanding of space and time. No longer viewed as distinct dimensions, relativity conceives of them as a singular, four-dimensional manifold known as spacetime. This revolutionary perspective is evident in special relativity, particularly through the Minkowski metric, which intricately weaves spatial and temporal components into its definition of distance. General relativity further deepens this integration, uniquely connecting the concept of mass to the very curvature of spacetime, suggesting a dynamic, interconnected cosmic structure. Even quantum cosmology offers its own innovative take, proposing a classical notion of spacetime where the entire world can be seen as one immense wave function, probabilistically expressing the location of particles.

2. **Monism and Pluralism: The World’s Unity or Multiplicity**

The fundamental question of whether the world is ultimately one or many lies at the heart of the philosophical debate between monism and pluralism. Monism, at its core, is a thesis of oneness, asserting that in a certain sense, only one thing truly exists. Its antithesis, pluralism, conversely posits that there is more than one existing thing. These two stances offer radically different architectures for understanding the foundational components of reality, profoundly impacting how we perceive every object and interaction.

Among the various forms of monism, “existence monism” stands out by declaring that the world itself is the sole concrete object that exists. From this perspective, all the seemingly discrete concrete “objects” we encounter daily—be it an apple, a car, or even ourselves—are not considered true objects in a strict sense. Instead, they are viewed as mere dependent aspects of this singular, overarching world-object. This world-object is often characterized as simple, lacking any genuine internal parts, leading to its intriguing description as a “blobject” due to its lack of internal structure.

“Priority monism” offers a slightly less radical but equally compelling view. While it allows for the existence of other concrete objects besides the world, it maintains that these objects do not possess the most fundamental form of existence. Instead, their being is somehow contingent upon and derived from the existence of the world as a whole. Conversely, the corresponding forms of pluralism assert that the world is inherently complex, not simple. It is fundamentally composed of multiple concrete, independent objects, each with its own fundamental existence, interacting within the larger totality rather than merely being an aspect of it.

3. **Theories of Modality: Exploring Possible Worlds**

In modern philosophy, particularly within theories of modality, the concept of “possible worlds” serves as an incredibly powerful and “innovative invention” for exploring the different ways reality could have been. A possible world is precisely defined as “a complete and consistent way how things could have been.” This conceptual tool allows philosophers to analyze necessity, possibility, and contingency by imagining alternative scenarios that are logically coherent, even if they are not actual.

The actual world—the one we currently inhabit—is, in itself, considered just one of these countless possible worlds, as “the way things are is a way things could have been.” However, the sheer vastness of other possibilities quickly becomes apparent. For instance, while Hillary Clinton did not win the 2016 US election, it is entirely conceivable that she *could* have. Therefore, a distinct possible world exists where she did indeed emerge victorious. This logic extends to an immense, almost infinite, number of possible worlds, each corresponding to even the slightest variation, provided no outright logical contradictions are introduced.

The nature of these possible worlds has itself been a subject of considerable debate. Many philosophers conceive of them as abstract objects, describing them as non-obtaining states of affairs or as maximally consistent sets of propositions. Under such a view, these abstract possible worlds might even be considered part of the actual world.

However, a highly influential alternative, championed by David Lewis, posits possible worlds as concrete entities. On Lewis’s bold conception, there is no fundamental difference in kind between the actual world and other possible worlds; both are seen as concrete, inclusive, and internally spatiotemporally connected totalities. The distinguishing factor is simply that the actual world is the one *we* inhabit, while other possible worlds are inhabited by our “counterparts.” Crucially, these different concrete worlds do not share a common spacetime, remaining “spatiotemporally isolated from each other,” a key feature that defines them as separate worlds. Furthermore, the discussion even extends to “impossible worlds”—ways things could *not* have been, involving contradictions—yet, like possible worlds, they are conceived as totalities of their constituents.

4. **Phenomenology: The World as Horizon of Experience**

Within the philosophical school of phenomenology, the “world” is uniquely defined not as an objective, external entity, but dynamically in terms of the “horizons of experiences” that constitute our conscious awareness. This approach shifts the focus from a detached, abstract understanding of reality to an immersive, lived experience, highlighting how our perception inherently shapes our understanding of the world around us. It’s a deeply personal and immediate conceptualization, emphasizing the subjective framework through which reality unfolds for us.

When we perceive an object, say a house, our attention isn’t solely fixed on that central object. Instead, we also simultaneously apprehend various other objects that surround it, even if they remain in the periphery of our awareness. The term “horizon” in phenomenology specifically refers to these “co-given objects”—elements that are usually experienced in a vague, indeterminate manner but are nonetheless integral to the complete perception. For instance, the perception of a house isn’t just about the structure itself; it implicitly includes horizons corresponding to the neighborhood, the city, the country, and ultimately, the Earth.

In this experiential context, the “world” achieves its ultimate definition as the “biggest horizon” or, more profoundly, the “horizon of all horizons.” This signifies an all-encompassing, ultimate framework of meaning and potential experience that grounds every individual perception. Phenomenologists further enrich this understanding by noting that the world is not merely a spatiotemporal collection of objects. Crucially, it also incorporates a complex web of relations between these objects. These can include “indication-relations,” which enable us to anticipate one object based on the appearance of another, and “means-end-relations” or “functional involvements” that are deeply relevant to our practical engagement with the world.

Read more about: The World Unveiled: Exploring Reality’s Multifaceted Meanings Across Disciplines

5. **Philosophy of Mind: The Mind-World Divide**

In the philosophy of mind, the term “world” takes on a specific and often contrasting role, typically used in opposition to the “mind.” Here, the world is conceptualized as “that which is represented by the mind,” establishing a fundamental distinction that drives much of the inquiry in this field. This foundational contrast posits a significant “gap between mind and world,” a chasm that, according to this view, must be successfully navigated and overcome for genuine mental representation to occur. It frames the human experience as an ongoing attempt to bridge this divide.

A core problem within the philosophy of mind is precisely to explain how the mind manages to bridge this representational gap. This involves elucidating the mechanisms by which the mind enters into authentic “mind-world-relations,” manifested in crucial cognitive functions such as perception, knowledge, and action. The successful establishment of these relations is not merely an academic concern; it is deemed essential for the world to be able to rationally constrain the activity of the mind, ensuring that our thoughts and beliefs are grounded in, and responsive to, external reality.

Different philosophical positions offer varied interpretations of this mind-world relationship. A “realist position” asserts that the world exists distinctly and independently from the mind, implying an objective reality that would persist even without a perceiving consciousness. In stark contrast, “idealists” contend that the world is either partially or entirely determined by the mind. Immanuel Kant’s transcendental idealism, for example, proposes that while reality exists independently, the fundamental spatiotemporal structure of the world—how we experience space and time—is imposed by the mind itself, lacking an independent existence otherwise. A more radical idealist stance is found in George Berkeley’s subjective idealism, which famously maintains that the world as a whole, including all everyday objects like tables, cats, trees, and ourselves, “consists of nothing but minds and ideas,” collapsing the distinction entirely into mental phenomena.

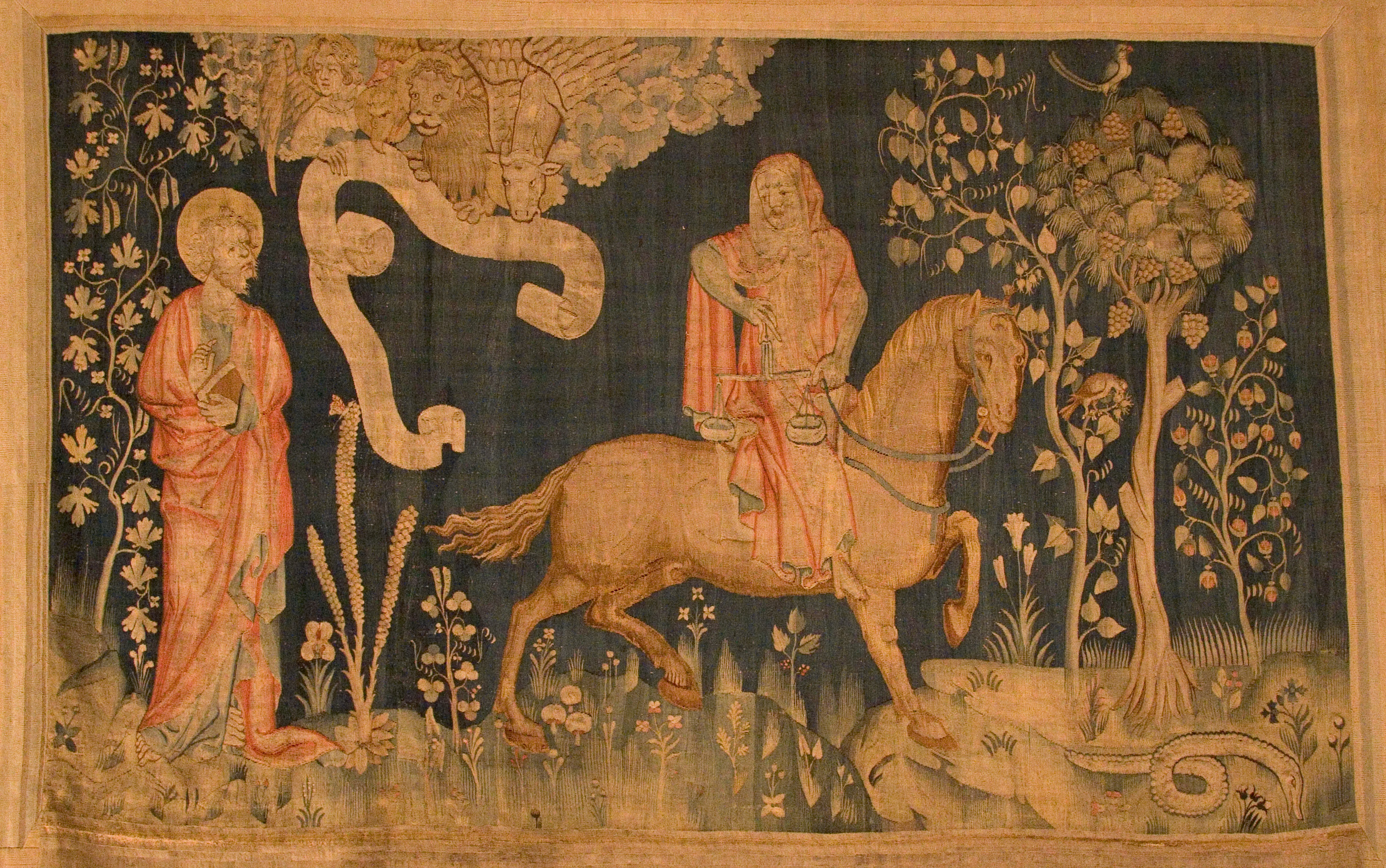

6. **Theology: The World in Divine Relation**

Across various theological traditions, the “world” is conceptualized in deeply profound and diverse ways, always in relation to the divine. These conceptualizations offer not just a cosmological framework but also imbue existence with purpose, meaning, and moral implications, reflecting humanity’s perennial search for ultimate origins and destinies. Each religious perspective presents a unique “blueprint” for the world’s place within a sacred order.

“Classical theism” posits that God is entirely distinct from the world. Despite this separation, the world’s very existence is utterly dependent on God, not only because “God created the world” but also because He continuously “maintains or conserves it.” This relationship is sometimes likened to how humans generate and sustain ideas in their imagination, albeit with the divine mind possessing infinitely greater power. In this view, God holds an “absolute, ultimate reality,” contrasting with the “lower ontological status ascribed to the world.” God’s engagement with creation is often seen through the lens of a personal, benevolent deity who actively “looks after and guides His creation.”

Other theological perspectives introduce variations on this theme. “Deists” concur with theists regarding God’s role in creating the world but diverge by denying any subsequent, personal involvement or intervention in its affairs. The world, once set in motion, operates according to its own natural laws. “Pantheists,” on the other hand, boldly reject the separation between God and world altogether, asserting their outright identity. This means that “there is nothing to the world that does not belong to God and that there is nothing to God beyond what is found in the world.” Finally, “Panentheism” offers a nuanced middle ground between theism and pantheism. While it holds, against theism, that God and the world are “interrelated and depend on each other,” it also maintains, against pantheism, that “there is no outright identity between the two,” suggesting God transcends yet encompasses the world.

Having journeyed through foundational scientific and philosophical conceptualizations of the world, we now pivot to explore even more groundbreaking ideas. This second section delves into further historical philosophical views, radical contemporary theories, and the profound implications that arise from contemplating the world’s origin, its ultimate end, and the diverse ways humans interpret its very nature. These conceptualizations are not just intellectual curiosities; they are innovative frameworks that continually reshape our understanding of what it means to exist within, and define, reality itself.

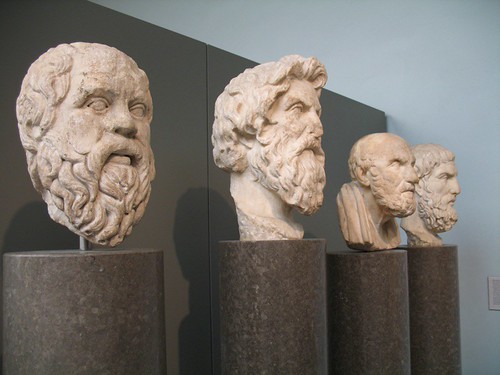

7. **Plato’s Dual Worlds: Sensible and Intelligible**

Among the most enduring and influential historical philosophical views is Plato’s theory of forms, which boldly posits the existence of two fundamentally distinct worlds. This dualistic framework, central to Platonic thought, challenges our everyday perception of reality by suggesting that what we see and touch is merely a shadow of a more perfect and eternal existence. It’s a conceptual invention that has shaped Western philosophy for millennia, pushing thinkers to look beyond the immediate.

Plato described the “sensible world” as the one we inhabit, a realm brimming with changing physical things that we can perceive and interact with using our senses. However, he assigned a “lower ontological status” to this world. Its existence is not fully independent; rather, physical things derive their reality from their “participation in the forms that characterize them.” This means the sensible world is, in essence, an imitation, constantly fluctuating and never quite achieving the perfection of its true exemplars.

In stark contrast to this changing, imperfect sensible world, Plato envisioned the “intelligible world.” This is a realm of “invisible, eternal, changeless forms” such as goodness, beauty, unity, and sameness. These forms possess an “independent manner of existence” and serve as the perfect blueprints for everything in the sensible world. They are the true reality, and our physical world is merely a replication that “never lives up to the original.”

To illustrate this profound distinction, Plato famously presented the “allegory of the cave.” In this powerful metaphor, he likened the physical things we perceive to “mere shadows of the real things.” The prisoners in the cave, unaware of the true source of these shadows, mistakenly believe them to be the entirety of reality. This allegory vividly portrays how our sensory experience can deceive us, urging us to seek a deeper, more profound truth found in the intelligible world of forms.

8. **Eugen Fink: The Cosmological Difference and the World as Play**

Eugen Fink, a prominent figure in 20th-century philosophy, introduced a radical contemporary idea concerning the nature of the world, criticizing what he perceived as a “misguided tendency in western philosophy.” He argued against the common view that understands the world simply as an “enormously big thing containing all the small everyday things we are familiar with.” For Fink, this perspective represented a “forgetfulness of the world,” overlooking its unique and foundational role.

To counteract this tendency, Fink proposed what he termed the “cosmological difference”: the fundamental distinction “between the world and the inner-worldly things it contains.” On his view, the world is not just a container but the “totality of the inner-worldly things that transcends them.” It is itself “groundless” yet it simultaneously “provides a ground for things.” This innovative concept positions the world as something far more profound than a mere collection or backdrop.

The world, in Fink’s philosophy, is what “gives appearance to inner-worldly things.” It furnishes them with “a place, a beginning and an end.” This goes beyond a simple spatial or temporal arrangement; it suggests an active role in defining the very conditions of existence for everything within it. Understanding this dynamic relationship is crucial to grasping Fink’s nuanced conceptualization of reality.

Investigating the world, according to Fink, presents a unique challenge because “we never encounter it since it is not just one more thing that appears to us.” This inherent elusiveness led him to employ the notion of “play” to illuminate the world’s nature. He saw play as a powerful “symbol of the world that is both part of it and that represents it,” highlighting how the “play-world” of imagination, like the real world, is more than just the sum of its apparent realities.

9. **Nelson Goodman: The Plurality of Actual Worlds**

Nelson Goodman, another influential contemporary philosopher, advanced a truly radical idea that challenges conventional notions of reality: the concept of a “plurality not of possible but of actual worlds.” This perspective emerges from his assertion that “we need to posit different worlds in order to account for the fact that there are different incompatible truths found in reality.” It’s an intellectual invention that forces us to reconsider the very singularity of our existence.

Goodman’s argument hinges on the existence of “incompatible truths,” which occur when different claims ascribe contradictory properties to the same thing. A prime example is the assertion that “the earth moves” alongside the claim that “the earth is at rest.” These statements, though mutually exclusive, each correspond to valid “world versions”—distinct ways of describing the world, such as heliocentrism and geocentrism. For Goodman, a “world version is true if it corresponds to a world,” meaning these incompatible truths must, by logical extension, refer to different worlds.

While theories of modality commonly posit a plurality of *possible* worlds, Goodman’s assertion of *actual* worlds introduces a significant philosophical challenge. If worlds are typically defined as “maximally inclusive wholes,” then the idea of a plurality of actual worlds “is in danger of involving a contradiction,” as one totality cannot logically exist alongside another. This problem arises because an all-inclusive world cannot have anything outside itself.

To navigate this paradox, Goodman’s world-concept can be interpreted not as “maximally inclusive wholes in the absolute sense” but rather “in relation to its corresponding world-version.” In this nuanced view, “a world contains all and only the entities that its world-version describes.” This innovative approach allows for multiple actual worlds to coexist without logical contradiction, as each is a complete totality only within the specific framework of its defining description.

10. **Worldviews: Subjective Representations of Reality**

Moving from specific philosophical constructs to a broader human interpretation, the concept of a “worldview” stands as an innovative invention in how we frame our understanding of existence. A worldview is defined as “a comprehensive representation of the world and our place in it.” It is fundamentally “a subjective perspective of the world,” distinguishing it from the objective reality it seeks to describe. This powerful mental construct is essential for human navigation and interaction with our environment.

While all higher animals develop some form of environmental representation to survive, it is argued that only humans possess a representation expansive enough to qualify as a “worldview.” Philosophers of worldviews emphasize that “the understanding of any object depends on a worldview constituting the background on which this understanding can take place.” This implies that our worldview influences not only our intellectual comprehension but also the very “experience of it in general.”

A critical aspect of worldviews is that it’s “impossible to assess one’s worldview from a neutral perspective,” as any such evaluation “already presupposes the worldview as its background.” This deep embedding makes them fundamental to human thought. Some interpretations even suggest that each worldview is built upon “a single hypothesis that promises to solve all the problems of our existence,” closely associating them with the comprehensive frameworks offered by different religions.

Beyond theoretical understanding, worldviews provide vital “orientation not just in theoretical matters but also in practical matters.” They typically encompass “answers to the question of the meaning of life and other evaluative components about what matters and how we should act.” While a worldview can be individual, they are more commonly “shared by many people within a certain culture or religion,” shaping collective identity and societal norms.

11. **Cosmogony: Unraveling the World’s Origin**

The inherent human quest to understand “the profound implications of its origin” gives rise to cosmogony, a field dedicated to studying “the origin or creation of the world.” This encompasses both rigorous “scientific cosmogony” and the rich tapestry of “creation myths found in various religions.” It is a testament to humanity’s enduring curiosity about how everything began, applying both empirical and narrative approaches to this ultimate question.

In the realm of scientific cosmogony, the preeminent theory is the “Big Bang theory.” This model proposes that “both space, time and matter have their origin in one initial singularity occurring about 13.8 billion years ago.” Following this singularity, a rapid “expansion that allowed the universe to sufficiently cool down for the formation of subatomic particles and later atoms.” These fundamental elements then converged, forming “giant clouds, which would then coalesce into stars and galaxies,” laying the cosmic groundwork for all structures we observe today.

Beyond the scientific narrative, “non-scientific creation myths are found in many cultures,” often serving a vital role in expressing “their symbolic meaning” through rituals. These myths offer diverse explanations for the world’s genesis. They can be broadly categorized by their content, including common types such as creation “from nothing,” “from chaos,” or from a “cosmic egg,” each providing a culturally specific account of the primordial state and the act of creation.

12. **Eschatology: Conceptions of the World’s End**

Just as humanity ponders the world’s beginning, so too does it grapple with “the profound implications of its end,” a study known as eschatology. This field refers to “the science or doctrine of the last things or of the end of the world.” Traditionally, eschatology has been “associated with religion, specifically with the Abrahamic religions,” where it often includes teachings on both the conclusion of individual human life and the ultimate cessation of the world as a whole.

However, the innovative concept of eschatology has also found application beyond religious contexts, notably in “physical eschatology.” This branch involves “scientifically based speculations about the far future of the universe,” utilizing current astrophysical understanding to model potential scenarios for cosmic demise. It’s a fascinating intersection of science and ultimate questions, pushing the boundaries of what can be predicted or theorized about the universe’s ultimate fate.

Among the models proposed in physical eschatology, some predict a “Big Crunch,” a scenario “in which the whole universe collapses back into a singularity, possibly resulting in a second Big Bang afterward.” This cyclical view suggests a universe that might eternally expand and contract. However, “current astronomical evidence seems to suggest that our universe will continue to expand indefinitely,” pointing towards a different, more drawn-out end, potentially a “Big Freeze” or “Big Rip,” though these are not explicitly detailed in the given context.

13. **The Paradox of Many Worlds: Reconciling Totality and Plurality**

One of the most intriguing conceptual challenges in defining “the world” is the apparent “paradox of many worlds.” While various fields, from theories of modality to quantum mechanics, readily embrace the idea of “many different worlds”—and even everyday language refers to distinct “worlds” like the “world of music” or “Asian world”—there’s an inherent tension. Worlds are simultaneously “usually defined as all-inclusive totalities,” implying that “if a world is total and all-inclusive then it cannot have anything outside itself.”

This definition creates a seemingly insurmountable contradiction: “Understood this way, a world can neither have other worlds besides itself or be part of something bigger.” The paradox highlights a fundamental difficulty in reconciling the intuitive notion of multiple distinct realities with the logical requirement of a truly all-encompassing whole. It forces a deeper examination of what we truly mean when we use the term “world.”

One innovative approach to resolving this paradox, while still maintaining the idea of a plurality of worlds, is to “restrict the sense in which worlds are totalities.” This perspective posits that worlds are “not totalities in an absolute sense,” allowing for their coexistence without logical conflict. Alternatively, some interpretations suggest that, in a strict sense, “there are no worlds at all,” or that worlds function “in a schematic sense: as context-dependent expressions that stand for the current domain of discourse,” meaning the definition of “world” adapts to the specific context, like referring to Earth in “Around the World in Eighty Days” or North and South America in “the New World.”

These thirteen groundbreaking conceptualizations, from ancient philosophical divisions to modern cosmological dilemmas, illuminate the sheer depth of human thought dedicated to understanding the ultimate totality of existence. Each “invention” in this intellectual journey provides a unique lens, a distinct framework for grasping reality. They reveal not just how we perceive the world, but how we constantly strive to define, question, and ultimately shape our place within its boundless expanse. As we continue our relentless pursuit of knowledge, these diverse “mechanics” of understanding will undoubtedly continue to evolve, pushing the boundaries of what we conceive “the world” to be. It’s an ongoing, fascinating adventure into the very heart of existence, one that truly demonstrates the incredible ingenuity of the human mind.