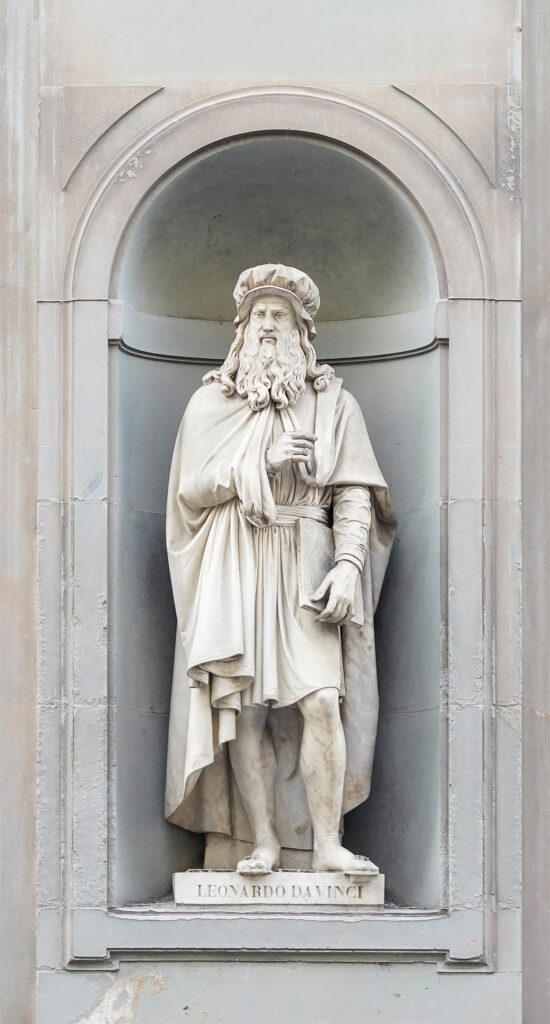

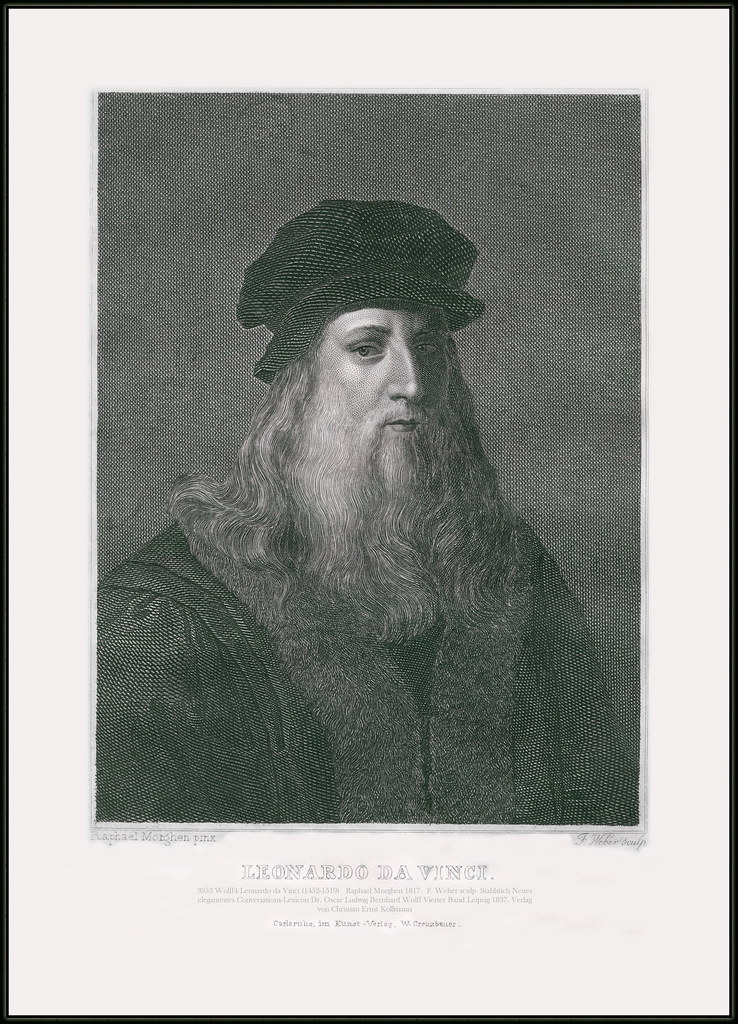

In the annals of human history, few figures shine as brightly or inspire as much awe as Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci. An Italian polymath of the High Renaissance, he was not merely a painter but also a draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. His very name has become synonymous with genius, encapsulating the ideal of the Renaissance humanist, a person whose intellectual curiosity and creative prowess knew no bounds.

While his initial renown was firmly established through his breathtaking achievements as a painter, Leonardo’s collective works extend far beyond the canvas. His comprehensive notebooks, filled with intricate drawings and profound observations on an astonishing array of subjects, offer an unparalleled glimpse into the mind of a man who constantly sought to understand and master the world around him. These records reveal a restless intellect, dedicated to inquiry across disciplines, from anatomy to astronomy, botany to cartography.

This article embarks on an in-depth exploration of Leonardo da Vinci’s extraordinary life and multifaceted career. We will traverse his pivotal early years, his transformative apprenticeships, and the groundbreaking commissions that defined his artistic and scientific journey. From his earliest brushstrokes to his visionary engineering concepts, we will uncover the foundational elements that shaped one of history’s most influential and admired minds.

1. **The Quintessential Renaissance Polymath: A Harmonious Blend of Art and Science**

Leonardo da Vinci stands as the quintessential Italian polymath of the High Renaissance, a figure who seamlessly blended artistic mastery with scientific inquiry. He was not content to excel in a single domain, but instead pursued knowledge and skill across an astonishing spectrum of disciplines. This innate versatility saw him active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect, embodying a breadth of talent rarely seen in any individual.

His fame, while initially resting on his unparalleled achievements as a painter, significantly expanded with the later recognition of his meticulous notebooks. These personal archives are a testament to his boundless curiosity, filled with detailed drawings and extensive notes on subjects as diverse as anatomy, astronomy, botany, cartography, painting, and palaeontology. They offer invaluable insights into his empirical thinking and his tireless quest for understanding.

Leonardo is widely regarded as a genius, a personification of the Renaissance humanist ideal that championed human potential and achievement across all fields of endeavor. The sheer volume and profound impact of his collective works have left an indelible mark on subsequent generations of artists and thinkers. Indeed, his contribution to the artistic and intellectual landscape is matched only by that of his younger contemporary, Michelangelo, firmly establishing Leonardo as a pivotal figure and often credited as the founder of the High Renaissance.

2. **Early Life and Verrocchio’s Workshop: The Genesis of a Master**

Leonardo da Vinci, properly named Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci, which translates to “Leonardo, son of ser Piero from Vinci,” was born on 15 April 1452. His birthplace was in, or near, the Tuscan hill town of Vinci, approximately 20 miles from Florence. Born out of wedlock to Piero da Vinci, a successful Florentine legal notary, and Caterina di Meo Lippi, a woman from the lower class, his early life was marked by humble origins that belied his future greatness.

Much of Leonardo’s childhood remains shrouded in myth and very little is definitively known, partly due to the often apocryphal accounts in 16th-century art historian Giorgio Vasari’s *Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects*. Tax records suggest he lived with his paternal grandfather, Antonio da Vinci, by at least 1457, although he may have spent earlier years in his mother’s care. His education was basic and informal, focusing on vernacular writing, reading, and mathematics, likely because his exceptional artistic talents were recognized early, prompting his family to direct their attention there.

In the mid-1460s, Leonardo’s family relocated to Florence, a vibrant epicenter of Christian Humanist thought and culture. Around the age of 14, he began his formal artistic journey as a *garzone*, or studio boy, in the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio. Verrocchio was then the leading Florentine painter and sculptor, and Leonardo officially became an apprentice by the age of 17, remaining under his tutelage for seven crucial years.

Verrocchio’s workshop was a fertile ground for artistic development, exposing Leonardo to both theoretical training and a vast array of technical skills. These included not just the artistic disciplines of drawing, painting, sculpting, and modelling, but also practical crafts such as drafting, chemistry, metallurgy, metal working, plaster casting, leather working, mechanics, and woodwork. This comprehensive exposure formed the bedrock of his later polymathic pursuits.

During his apprenticeship, Leonardo collaborated with Verrocchio on works like *The Baptism of Christ* (c. 1472–1475). Vasari recounts that Leonardo’s painting of the young angel holding Jesus’s robe displayed such superior skill that Verrocchio reputedly laid down his brush and never painted again, though this claim is widely considered apocryphal. The application of the new technique of oil paint to areas of this predominantly tempera work, including the landscape and parts of Jesus’s figure, strongly suggests Leonardo’s hand in its creation.

3. **The First Florentine Flourish: Emerging Independence and Early Masterpieces**

By 1472, at the youthful age of 20, Leonardo had achieved the significant milestone of qualifying as a master in the Guild of Saint Luke, the esteemed guild of artists and doctors of medicine. Despite this professional independence, his deep attachment to Verrocchio led him to continue collaborating and even living with his former master, a testament to the formative influence of his early training.

His emerging independence was formally marked in January 1478, when Leonardo received his first independent commission: to paint an altarpiece for the Chapel of Saint Bernard in Florence’s town hall, the Palazzo della Signoria. This commission was a clear indication of his professional separation from Verrocchio’s studio. Further demonstrating his rising stature, in March 1481, he received another significant commission from the monks of San Donato in Scopeto for *The Adoration of the Magi*.

During this period, Leonardo also cultivated significant connections with the powerful Medici family. An anonymous early biographer, known as Anonimo Gaddiano, states that by 1480 Leonardo was living with the Medici and frequently worked in the garden of the Piazza San Marco in Florence. This location was a hub for the Neoplatonic academy of artists, poets, and philosophers organized by the Medici, where Leonardo encountered influential Humanist thinkers such as Marsiglio Ficino and the brilliant young poet and philosopher Pico della Mirandola.

Leonardo’s earliest known dated work, a pen-and-ink drawing of the Arno valley from 1473, hails from this period, showcasing his early mastery of landscape. Vasari also attributes to the young Leonardo the innovative suggestion of making the Arno river a navigable channel between Florence and Pisa, foreshadowing his later engineering interests. Other significant works from his first Florentine period include the *Madonna of the Carnation*, *Ginevra de’ Benci*, and *Benois Madonna*, each demonstrating his developing skill in capturing human emotion and form.

4. **Milanese Patronage and Architectural Ambitions: The Gran Cavallo and Sala delle Asse**

Leonardo’s career took a significant turn in 1482 when he was dispatched as an ambassador by Lorenzo de’ Medici to Ludovico il Moro, who governed Milan from 1479 to 1499. He remained in Milan, working under Ludovico’s patronage, until 1499. His initial appeal to Sforza was an extraordinary letter detailing his diverse capabilities, not only in painting but also, and prominently, in the fields of engineering and weapon design. To further impress, he brought with him a unique silver string instrument shaped like a horse’s head.

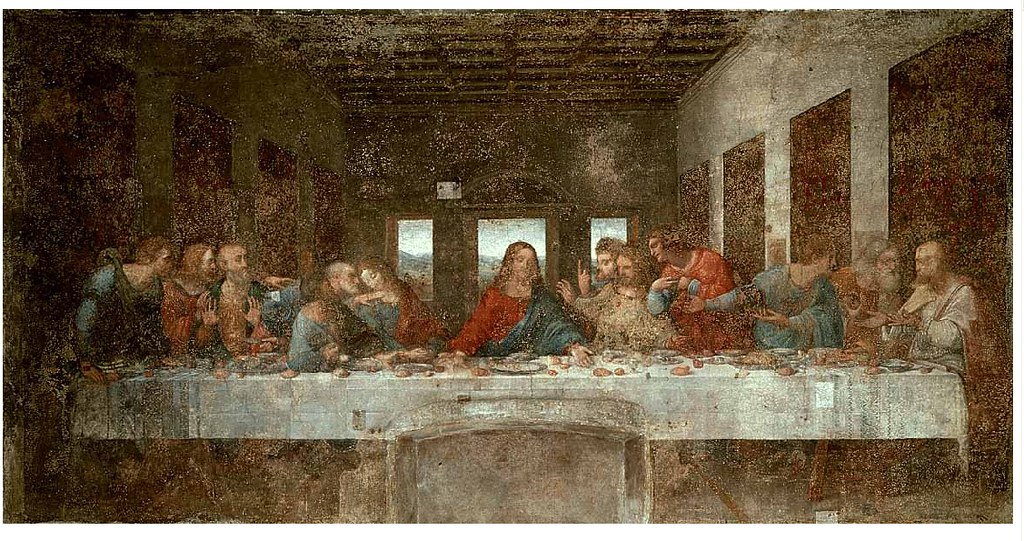

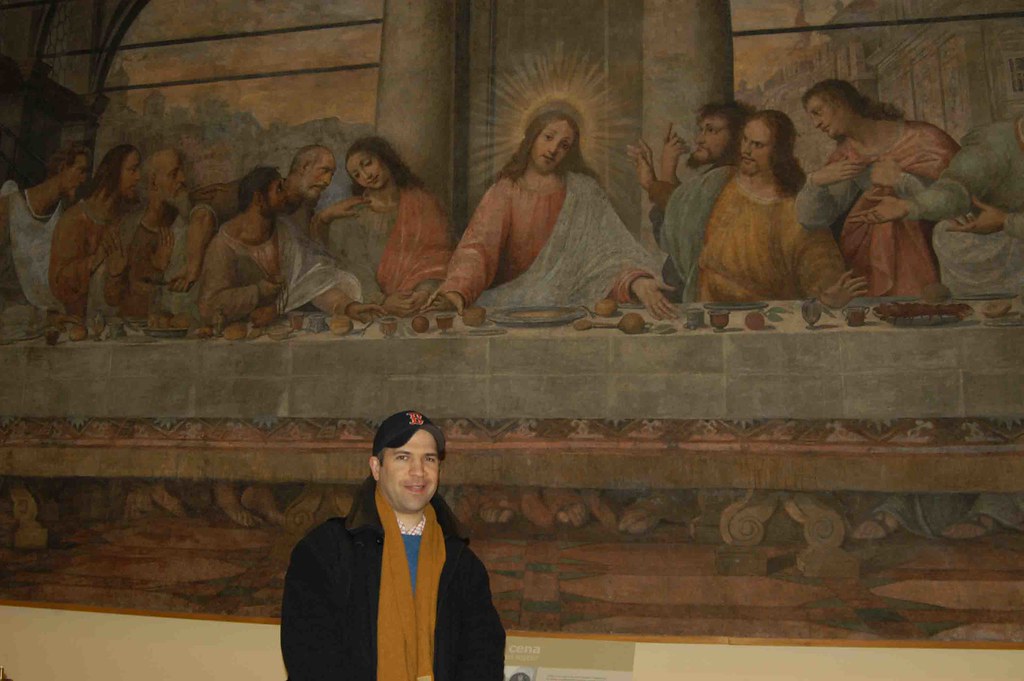

During his first Milanese period, Leonardo secured two of his most iconic painting commissions. He was tasked with painting the *Virgin of the Rocks* for the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception, and the monumental *The Last Supper* for the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie. These works would cement his reputation as a master painter and innovator in composition and psychological depth.

Beyond painting, Leonardo was engaged in a wide array of projects for Sforza, reflecting the Duke’s diverse interests and Leonardo’s versatile talents. These included designing elaborate floats and pageants for special occasions, creating a drawing and a wooden model for a competition to design the cupola of Milan Cathedral, and working on plans for a colossal equestrian monument.

This grand monument, known as the *Gran Cavallo*, was intended to honor Ludovico’s predecessor, Francesco Sforza. It was conceived to surpass in sheer size the only two other large equestrian statues of the Renaissance: Donatello’s *Gattamelata* in Padua and Verrocchio’s *Bartolomeo Colleoni* in Venice. Leonardo poured years into the project, completing a magnificent clay model for the horse and developing detailed plans for its intricate casting. However, in November 1494, a cruel twist of fate saw Ludovico divert the precious metal intended for the statue to be used for cannons, needed to defend the city against Charles VIII of France, leaving the monumental project tragically unfinished.

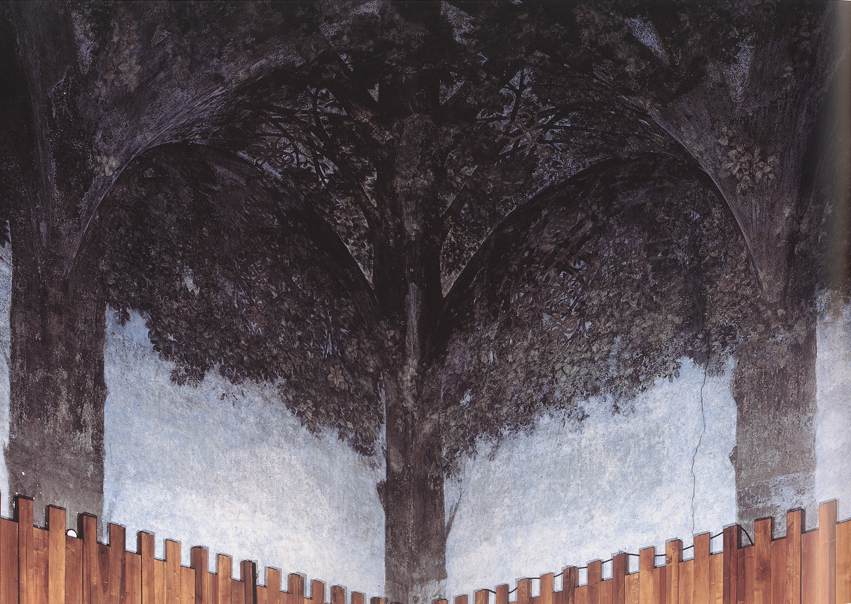

Another notable architectural and artistic endeavor from this period was the *Sala delle Asse* in the Sforza Castle. Around 1498, contemporary correspondence records that Leonardo and his assistants were commissioned by the Duke of Milan to paint this hall. The project culminated in a spectacular *trompe-l’œil* decoration, transforming the great hall into an immersive pergola. This illusion was created by the interwoven limbs of sixteen mulberry trees, whose expansive canopy adorned the ceiling with an intricate labyrinth of leaves and knots, demonstrating Leonardo’s mastery of perspective and naturalistic detail.

5. **Engineering Visionary: Conceptualizing Machines Beyond His Time**

Leonardo da Vinci’s mind was not confined to the artistic realm; he was also revered for his extraordinary technological ingenuity. His notebooks are replete with conceptual designs for machines that were often centuries ahead of their time, showcasing a visionary intellect that grappled with the principles of mechanics, aerodynamics, and structural engineering. He envisioned groundbreaking innovations that would not become practical realities until much later periods of scientific and industrial advancement.

Among his remarkable conceptualizations were designs for flying machines, a precursor to the modern aircraft, and a type of armored fighting vehicle, an early blueprint for the tank. He also conceived of concentrated solar power, harnessing the sun’s energy, and a ratio machine that could be adapted for use in an adding machine, demonstrating an understanding of complex calculations. His designs even extended to the double hull, a concept later adopted for maritime safety.

Despite the brilliance of these designs, relatively few of Leonardo’s inventions were ever constructed, or even feasible, during his own lifetime. The primary impediment was the nascent state of metallurgy and engineering during the Renaissance; the modern scientific approaches and material capabilities required to realize such ambitious concepts were simply in their infancy. His theoretical understanding often outstripped the practical means of his era.

However, it is worth noting that some of his smaller, less heralded inventions did find their way into the world of manufacturing, often without public acclaim. These included practical devices such as an automated bobbin winder, which would have significantly enhanced textile production, and a machine designed for testing the tensile strength of wire, highlighting his practical application of scientific principles to everyday problems. These demonstrate that while his grand visions often remained on paper, his smaller innovations found immediate utility.

Read more about: Decoding Da Vinci: A People Magazine Journey Through the Life and Legacy of the Renaissance’s Ultimate Genius

6. **Unpublished Scientific Discoveries: A Legacy Veiled in Notebooks**

Beyond his artistic and engineering feats, Leonardo da Vinci made substantial discoveries across a wide array of scientific disciplines. His relentless observation and empirical investigations led to profound insights in fields such as anatomy, civil engineering, hydrodynamics, geology, optics, and tribology. His approach was fundamentally scientific, driven by a desire to understand the underlying mechanisms and natural laws governing the world.

Crucially, however, Leonardo did not publish his findings. This decision, or perhaps lack of opportunity, meant that his groundbreaking discoveries had little to no direct influence on subsequent scientific thought or development. His meticulously documented insights remained largely confined within the pages of his private notebooks, only to be fully appreciated by later generations. This represents a significant missed opportunity for the acceleration of Renaissance science.

His scientific pursuits were diverse and intensely practical. For instance, he famously dissected cadavers, creating exquisitely detailed anatomical drawings and making comprehensive notes for a treatise on vocal cords. These dissections, conducted at a time when such practices were rare and often controversial, provided an unparalleled understanding of human physiology. He even attempted to use these findings to regain the Pope’s favor in Rome, presenting them to an official, though ultimately without success.

Furthermore, during his time in Rome, Leonardo practiced botany in the Vatican Gardens, meticulously studying plant structures and growth patterns. His observations in civil engineering extended to practical applications, such as being commissioned to make plans for the Pope’s proposed draining of the Pontine Marshes. These endeavors underscore his commitment to empirical study and problem-solving, applying his keen intellect to both theoretical understanding and practical challenges.

While his scientific treatises did not see widespread publication, Leonardo’s detailed knowledge, derived from these profound observations in anatomy, light, botany, and geology, profoundly informed his artistic output. This interdisciplinary approach imbued his paintings with an unprecedented realism and depth, making his figures and landscapes resonate with a scientific accuracy that was revolutionary for his era. It is within his art that his scientific spirit is most visibly expressed.

7. **The Last Supper: A Masterpiece of Narrative Drama and Human Emotion**

Leonardo’s most renowned painting from the 1490s, and arguably one of the most famous artworks in Western history, is *The Last Supper*. Commissioned for the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, this monumental mural depicts the final meal shared by Jesus with his twelve disciples before his betrayal and crucifixion. Leonardo chose to capture the dramatic moment when Jesus has just declared, “one of you will betray me,” vividly illustrating the profound consternation and varied emotional responses elicited by this revelation among the apostles.

Eyewitness accounts offer fascinating glimpses into Leonardo’s unique working methods for this masterpiece. The writer Matteo Bandello observed that Leonardo sometimes painted from dawn till dusk without pause, yet at other times would not touch his brush for three or four days, contemplating his work. This intermittent and introspective approach often baffled the prior of the convent, who relentlessly hounded Leonardo for its completion, forcing the artist to seek intervention from Duke Ludovico Sforza.

Vasari recounts an intriguing anecdote that highlights Leonardo’s struggle with capturing the perfect visages for Christ and the traitor Judas. Leonardo expressed his profound difficulty to the Duke, humorously suggesting that he might be compelled to use the importunate prior as his model for Judas. This story, whether entirely factual or embellished, underscores the intense psychological depth and characterization Leonardo sought to achieve in each figure.

Upon its completion, *The Last Supper* was immediately acclaimed as a masterpiece, lauded for its innovative design, dynamic composition, and extraordinary characterization of each individual apostle. It redefined how narrative moments could be depicted in art, bringing unprecedented psychological realism to a religious subject. Leonardo’s arrangement of the figures, their gestures, and expressions masterfully conveyed the shock, doubt, and loyalty inherent in the biblical narrative.

Tragically, despite its initial acclaim, the painting began to deteriorate rapidly. Within a mere hundred years of its creation, it was described by one viewer as “completely ruined.” This catastrophic decline was primarily due to Leonardo’s experimental technique; instead of employing the durable and reliable fresco method, he opted to use tempera over a ground that was mainly gesso. This unconventional approach resulted in a surface highly susceptible to mould and extensive flaking, a testament to his bold experimentation but also its unforeseen consequences. Despite its fragile state, and subsequent restorations, *The Last Supper* remains one of the most reproduced and revered works of art in history.

Read more about: Unveiling the Polymath: An Insider’s Deep Dive into Leonardo da Vinci’s Life and Groundbreaking Works

8. **The Second Florentine Flourish: Return to the Cradle of the Renaissance**

After the French overthrow of Ludovico Sforza in 1500, Leonardo found himself relocating from Milan, first to Venice, where he served briefly as a military architect and engineer, devising crucial defense strategies against naval attacks. His genius was thus not confined to the easel, but readily adapted to the pressing needs of statecraft and defense, a testament to his boundless practicality and intellectual agility. This transient period soon brought him back to his artistic heartland, Florence, in 1500.

Upon his return to the bustling Florentine republic, Leonardo and his entourage were welcomed as guests by the Servite monks at the monastery of Santissima Annunziata. Here, he was provided with a workshop, a fertile ground where, as Vasari recounts, he created the cartoon for *The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and Saint John the Baptist*. This particular work garnered immense public adoration, drawing crowds of “men [and] women, young and old” who flocked to witness it “as if they were going to a solemn festival,” showcasing the immediate and profound impact of his artistry.

In 1502, Leonardo briefly entered the service of Cesare Borgia, the formidable son of Pope Alexander VI, taking on the demanding role of military architect and engineer. This period saw him travelling extensively throughout Italy with his patron, creating meticulously detailed maps, such as the town plan of Imola, to secure Borgia’s patronage and enhance strategic positioning. He also conceived ambitious civil engineering projects, including a dam from the sea to Florence, designed to sustain the Arno canal year-round, further cementing his reputation for blending innovative thought with practical application.

Returning to Florence by early 1503, Leonardo formally rejoined the Guild of Saint Luke, signalling his re-engagement with the city’s artistic establishment. It was around this time, specifically in October, that he commenced work on a portrait that would eventually become arguably the most famous painting in the world: the *Mona Lisa*. This undertaking would occupy him for many years, a testament to his meticulous process and profound dedication to capturing an elusive essence on canvas.

His stature in Florence was undeniable, as evidenced by his participation in a pivotal committee in January 1504, tasked with determining the placement of Michelangelo’s monumental statue of David. He then dedicated two years to designing and painting a mural of *The Battle of Anghiari* for the Salone dei Cinquecento in the Palazzo Vecchio, intended to be a companion piece to Michelangelo’s *The Battle of Cascina*. Although Leonardo’s mural ultimately deteriorated rapidly, his dynamic composition of four men on raging war horses became known through copies, leaving its mark on artistic tradition.

By 1506, Leonardo was summoned back to Milan by Charles II d’Amboise, the city’s acting French governor, a move facilitated by the powerful Louis XII who harbored intentions of commissioning portraits from the master. During this period, he took on a new pupil, Count Francesco Melzi, the son of a Lombard aristocrat, who would become his favourite and most devoted student. While the Council of Florence pressed for his return to complete *The Battle of Anghiari*, royal influence allowed Leonardo to pursue his scientific interests more freely, though he also found himself navigating a dispute with his brothers over his father’s estate in Florence in 1507.

9. **The Enigmatic Smile: Unpacking the Mona Lisa’s Enduring Mystique**

Among the artistic masterpieces Leonardo crafted in the 16th century, one small portrait, often referred to as the *Mona Lisa* or *La Gioconda*, stands unparalleled in its global recognition. It is, without hyperbole, arguably the most famous painting in the entire world. The subject, Lisa del Giocondo, was painted over several years, a commitment that highlights Leonardo’s painstaking approach to capturing human essence and emotion.

The painting’s extraordinary fame rests largely on the subject’s elusive smile, a mysterious quality that has captivated viewers for centuries. This enigmatic expression is particularly attributed to the subtly shadowed corners of the mouth and eyes, which obscure its exact nature, leaving observers to ponder its meaning. This masterful play of light and shadow, creating a soft, hazy effect, became known as *sfumato*, or “Leonardo’s smoke,” a signature technique that added profound depth and psychological complexity to his works.

Giorgio Vasari, the renowned art historian, eloquently described the smile as “so pleasing that it seems more divine than human, and it was considered a wondrous thing that it was as lively as the smile of the living original.” This sentiment underscores the revolutionary realism and vitality Leonardo imbued in his subject, elevating portraiture to new heights. The unadorned dress of the sitter, deliberate in its simplicity, further ensures that the viewer’s focus remains intently on the eyes and hands, where the true emotional narrative unfolds without distraction.

Beyond the captivating smile, *Mona Lisa* is characterized by its dramatic landscape background, a world seemingly in a state of flux, providing a stark yet harmonious contrast to the serene figure. The subdued colouring contributes to the painting’s tranquil atmosphere, while the extremely smooth painterly technique, employing oils laid on much like tempera and blended so seamlessly that brushstrokes are indistinguishable, speaks to Leonardo’s unparalleled technical prowess. Vasari himself remarked that its quality would make even “the most confident master … despair and lose heart,” acknowledging its supreme artistic achievement.

Adding to its mystique and value, *Mona Lisa* boasts a perfect state of preservation, a rarity for a panel painting of its age, with no discernible signs of repair or overpainting. This immaculate condition allows contemporary audiences to experience the work almost precisely as Leonardo intended, a pristine window into the mind of a genius. Its global iconic status, transcending artistic circles to become a universal symbol of beauty and mystery, is a testament to Leonardo’s profound and enduring impact on culture.

10. **Later Milanese Encounters and Roman Years: New Patrons and Scientific Pursuits**

By 1508, Leonardo had once again returned to Milan, establishing his residence in Porta Orientale within the parish of Santa Babila. His creative output continued, and by 1512, he was engrossed in developing plans for another ambitious equestrian monument, this time dedicated to Gian Giacomo Trivulzio. However, fate, or rather the turbulent political climate of the era, intervened once more as an invasion by a confederation of Swiss, Spanish, and Venetian forces drove the French from Milan, bringing the project to an abrupt halt.

Despite the political upheaval, Leonardo chose to remain in the city, spending several months in 1513 at the Medici’s Vaprio d’Adda villa, a period that allowed him to continue his diverse intellectual pursuits amidst a more tranquil setting. His reputation, by now, preceded him, attracting patronage from the highest echelons of European society.

A significant shift occurred in September 1513 when Leonardo moved to Rome, following the assumption of the papacy by Lorenzo de’ Medici’s son Giovanni (as Leo X) in March. He was received by the pope’s brother, Giuliano, and for the next three years, until 1516, he resided in the Belvedere Courtyard of the Apostolic Palace, a vibrant hub where two other titans of the Renaissance, Michelangelo and Raphael, were also active. Here, Leonardo received a generous allowance of 33 ducats a month, and, in a quirky detail recounted by Vasari, even decorated a lizard with scales dipped in quicksilver, showcasing his playful curiosity.

The Pope did offer Leonardo a painting commission of an unknown subject. However, this promising opportunity was ultimately cancelled when the artist diverted his focus to developing a new kind of varnish, highlighting his unwavering dedication to experimental methods even at the expense of a direct papal commission. It was during this Roman period that Leonardo also experienced what may have been the first of multiple strokes that would ultimately lead to his death, a poignant reminder of his advanced age and persistent efforts.

Undeterred by health challenges, Leonardo continued his scientific investigations with characteristic zeal. He practiced botany in the Vatican Gardens, meticulously studying plant life and making detailed observations. His expertise in civil engineering was also called upon when he was commissioned to devise plans for the Pope’s ambitious project to drain the Pontine Marshes, a testament to his practical problem-solving skills being sought at the highest levels.

Furthermore, his anatomical studies persisted, marked by the dissection of cadavers and the creation of comprehensive notes for a treatise on vocal cords. He even presented these findings to an official, hoping to regain the Pope’s favor after the cancelled commission, though he was ultimately unsuccessful. These endeavors underscore his commitment to empirical observation and the advancement of knowledge, even when his personal fortunes wavered.

11. **The French Royal Court: Final Years and Lingering Genius**

The political landscape shifted dramatically in October 1515 when King Francis I of France successfully recaptured Milan, a pivotal event that would soon alter the course of Leonardo’s final years. Recognizing the unparalleled genius in their midst, the French royal court extended an invitation to Leonardo, eager to secure his talents. On 21 March 1516, the French ambassador to the Holy See, Antonio Maria Pallavicini, received royal instructions to assist Leonardo in his relocation to France, with King Francis I eagerly anticipating his arrival and reassuring him of a warm reception at court.

Later that year, Leonardo officially entered the service of King Francis I, a relationship that would blossom into a close friendship. He was granted the use of the picturesque manor house Clos Lucé, conveniently located near the King’s residence at the royal Château d’Amboise. Here, in the serene Loire Valley, Leonardo found a haven for his later years, frequently visited by the young and admiring monarch who sought his counsel and admired his creative spirit.

His work for the King included drawing plans for an immense castle town that Francis intended to erect at Romorantin, showcasing Leonardo’s continuing architectural ambitions and visionary urban planning capabilities. A particularly charming anecdote from this period involves his creation of a mechanical lion for a royal pageant. This intricate automaton, upon walking towards the King and being struck by a wand, ingeniously opened its chest to reveal a cluster of lilies, symbolizing the French monarchy and delighting the court with its mechanical marvel.

During these final years, Leonardo was accompanied by his loyal friend and apprentice, Francesco Melzi, who had become his favored student. Melzi provided not only companionship but also crucial assistance, ensuring that Leonardo’s intellectual legacy was carefully preserved. The artist was supported by a substantial pension totaling 10,000 scudi, affording him financial comfort and the freedom to continue his pursuits without constraint.

Melzi, deeply devoted to his master, created a poignant portrait of Leonardo during this time, capturing the visage of the aging genius. Other contemporary depictions, including a sketch by an unknown assistant from around 1517 and a drawing by Giovanni Ambrogio Figino, further provide glimpses of Leonardo in his later life. These records, particularly Figino’s depiction of an elderly Leonardo with his right arm wrapped in clothing, corroborate an account from an October 1517 visit by Louis d’Aragon, confirming that Leonardo’s right hand was paralytic by the age of 65. This physical limitation may explain why some of his magnificent works, such as the *Mona Lisa*, remained technically “unfinished” in his view. Despite this challenge, he continued to work in some capacity until illness eventually rendered him bedridden for several months.

12. **The Enduring Bond: Leonardo’s Personal Relationships and Companions**.

Despite the thousands of pages filled with intricate drawings and profound observations across his notebooks and manuscripts, Leonardo da Vinci scarcely made direct reference to his personal life. This reticence has, paradoxically, fueled centuries of curiosity and speculation about the man behind the genius, inviting scholars and biographers to piece together fragments of his private world. What is clear, however, is that his extraordinary intellect and “great physical beauty,” as described by Vasari, alongside his “infinite grace,” captivated those around him.

One particularly endearing aspect of his character was his profound love for animals, which Vasari records, noting his habit of purchasing caged birds merely to release them, a gesture that hints at a deep empathy and perhaps a philosophical stance aligned with vegetarianism. Beyond his artistic and scientific peers, Leonardo maintained friendships with notable figures like the mathematician Luca Pacioli, with whom he collaborated on the influential book *Divina proportione* in the 1490s, highlighting his intellectual camaraderie.

Interestingly, Leonardo appears to have had very few close relationships with women, beyond his friendships with Cecilia Gallerani, the probable subject of *Lady with an Ermine*, and the Este sisters, Beatrice and Isabella. While travelling through Mantua, he drew a portrait of Isabella, likely a preparatory study for a painted portrait that is now lost, further underscoring his selective but significant connections.

Yet, it is his most intimate relationships, particularly with his long-time pupils Salaì and Francesco Melzi, that have garnered the most sustained attention and discussion. Melzi, in a letter informing Leonardo’s brothers of his master’s death, described Leonardo’s feelings for his pupils as both “loving and passionate,” a poignant testament to the deep emotional bonds formed within his household. Since the 16th century, the nature of these relationships has been claimed by some to be ual or erotic, a perspective explicitly supported by Walter Isaacson in his biography of Leonardo.

Historical records, though scarce, offer glimpses into these complexities. In 1476, at the age of twenty-four, Leonardo and three other young men faced charges of sodomy involving a known male prostitute. The charges were ultimately dismissed for lack of evidence, with speculation that the powerful Medici family exerted its influence to secure the dismissal, given that one of the accused, Lionardo de Tornabuoni, was related to Lorenzo de’ Medici. This incident has been extensively discussed in relation to his presumed homouality and its potential influence on his art, particularly the androgynous and subtly erotic qualities observed in works such as *Saint John the Baptist* and *Bacchus*, and more explicitly in some of his erotic drawings.

Salaì, whose real name was Gian Giacomo Caprotti da Oreno, joined Leonardo’s household in 1490. Despite Leonardo dubbing him “The Little Unclean One” (Il Salaino) due to his mischievous nature – a list of misdemeanours included stealing money and valuables, and spending excessively on clothes – Leonardo treated him with remarkable indulgence. Salaì remained in Leonardo’s care for three decades, even executing paintings under his own name, though their artistic merit is generally considered lesser than that of other pupils like Marco d’Oggiono or Boltraffio. At his death in 1524, Salaì owned a painting referred to as *Joconda* in his inventory, valued at an exceptionally high 505 lire for a small panel portrait, hinting at a cherished possession and perhaps an enduring connection to his master’s most famous work.

Read more about: Decoding Da Vinci: A People Magazine Journey Through the Life and Legacy of the Renaissance’s Ultimate Genius

13. **Death and a Royal Eulogy: The Legacy’s Dawn**

Leonardo da Vinci, the incomparable polymath, passed away at Clos Lucé on May 2, 1519, at the age of 67, likely due to a stroke. His death marked the end of an extraordinary life, one that profoundly shaped the course of Western art and science. By this time, King Francis I of France, his patron and admirer, had become a remarkably close friend, often seeking the artist’s company and cherishing his intellectual contributions.

Vasari’s account, perhaps tinged with legend, describes Leonardo on his deathbed, lamenting with repentance that “he had offended against God and men by failing to practice his art as he should have done.” He further recounts that Leonardo, in his final days, requested a priest to hear his confession and administer the Holy Sacrament, reflecting a return to spiritual solace. The romanticized image of King Francis I holding Leonardo’s head in his arms as he died, while possibly apocryphal, powerfully symbolizes the deep respect and affection the monarch held for the dying genius.

In accordance with his meticulously prepared will, Leonardo ensured his final farewell was fittingly solemn, with sixty beggars carrying tapers accompanying his casket, a gesture reflecting his charitable spirit. Francesco Melzi, his devoted student and companion, was designated as the principal heir and executor, inheriting not only a substantial sum of money but also Leonardo’s invaluable paintings, tools, extensive library, and personal effects, thereby safeguarding a significant portion of his master’s legacy.

Leonardo’s other long-time pupil and companion, Salaì, along with his servant Baptista de Vilanis, each received half of Leonardo’s vineyards, a practical legacy reflecting their years of service. His brothers, though having minimal contact with him during his lifetime, received land, and his serving woman was bequeathed a fur-lined cloak. On August 12, 1519, Leonardo’s remains were interred in the Collegiate Church of Saint Florentin at the Château d’Amboise, a final resting place in the land where he spent his celebrated final years.

Approximately two decades after Leonardo’s passing, the renowned goldsmith and sculptor Benvenuto Cellini recorded King Francis I’s profound eulogy for the master. The King was reported to have declared: “There had never been another man born in the world who knew as much as Leonardo, not so much about painting, sculpture and architecture, as that he was a very great philosopher.” This poignant tribute from a monarch underscores the immense intellectual stature and multifaceted genius Leonardo commanded, confirming his status not merely as an artist, but as a sage whose wisdom transcended all disciplines.

14. **The Unfolding Influence: Leonardo’s Posthumous Impact and Cultural Iconography**

For centuries following his death, Leonardo da Vinci’s towering fame primarily rested upon his unparalleled achievements as a painter. His remarkable ability to imbue canvas with life, emotion, and profound depth earned him the title of “Divine” painter by the 1490s. While he left behind fewer than 25 attributed major works, many of them unfinished, this small collection includes some of the most influential paintings in the entire Western canon, each a testament to his groundbreaking vision.

His artistry is distinguished by a unique combination of innovative techniques, including his revolutionary approach to laying on paint and his meticulous understanding of anatomy, light, botany, and geology. He possessed an acute interest in physiognomy and the subtle ways humans register emotion through expression and gesture, which he masterfully captured. Furthermore, his innovative use of the human form in figurative composition and his subtle gradation of tone, famously known as *sfumato*, all converged to create works of unprecedented realism and psychological insight. These qualities are vibrantly evident in his most famous painted works, including *The Mona Lisa* and *The Virgin of the Rocks*, and indeed *The Last Supper*, which despite its early deterioration, remains one of the most reproduced religious paintings of all time.

In the modern era, while his artistic legacy remains central, a burgeoning awareness and admiration for Leonardo as a scientist and inventor have significantly broadened his posthumous appreciation. His notebooks, once private repositories of groundbreaking discoveries, are now seen as visionary blueprints, revealing a mind that conceptualized flying machines, armored vehicles, concentrated solar power, and the double hull, centuries before their practical realization. These theoretical leaps, though largely unpublished in his lifetime, confirm a scientific genius that paralleled his artistic prowess.

Leonardo’s impact extends far beyond the gallery or the scientific laboratory; he has permeated global culture, becoming a ubiquitous icon. His *Vitruvian Man* drawing, a perfect synthesis of art and science, depicting the ideal human proportions, is universally recognized as a cultural icon, symbolizing the harmonious balance of mind and body. The astounding sale of *Salvator Mundi*, attributed in whole or part to Leonardo, for a record-breaking US$450.3 million in 2017, further underscores his enduring market value and the insatiable fascination with his oeuvre.

Since his death in 1519, there has never been a moment when his achievements, his diverse interests, his enigmatic personal life, and his empirical thinking have failed to incite intense interest and widespread admiration. His name has become synonymous with genius itself, frequently invoked and studied across countless disciplines and cultural contexts. Leonardo da Vinci remains an eternal wellspring of inspiration, a figure whose unparalleled contribution to human knowledge and creativity continues to unfold and enchant generations, a true titan whose legacy is as boundless as his curiosity.