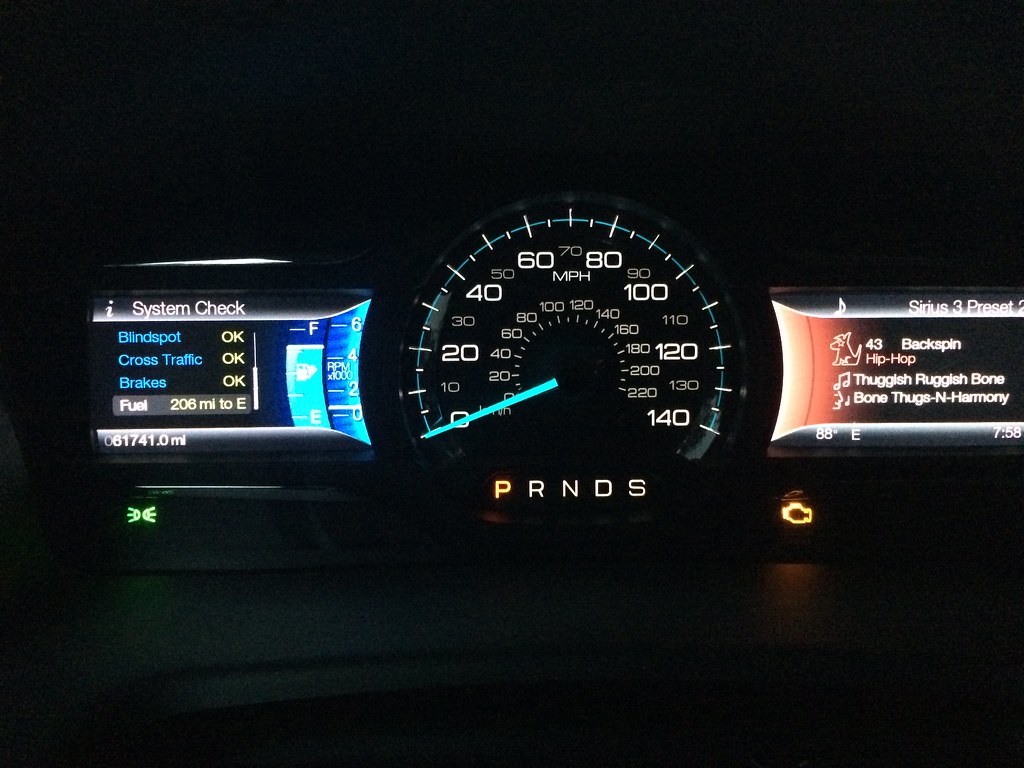

You’re driving along, minding your own business, when suddenly, that dreaded “Check Engine” light flickers to life on your dashboard. Immediately, a cascade of fears might rush through your mind: Is it something catastrophic? Am I about to break down? Is this going to cost a fortune? Often, these fears are amplified by misunderstandings, common “lies” about what that light truly signifies, much like linguistic “warning lights” can trigger alarm over word usage.

Consider the word “worst.” It’s a powerful superlative, but along with its root forms “bad” and “ill,” it’s surrounded by linguistic “lies”—misconceptions that lead to grammatical misfires, awkward phrasing, and even unintended meanings. These aren’t minor glitches; they’re pervasive errors that, much like a perpetually glowing check engine light, point to something amiss in our understanding of language’s true functions and nuances.

In this deep dive, we’re going to pull back the curtain on seven of these “worst lies” surrounding “worst” and its relatives, revealing the true mechanics of their usage. Our aim is to equip you with accurate, authoritative insights from the very “owner’s manual” of our language. By understanding these nuances, you’ll gain a more precise, powerful command over your words, transforming confusing “warning lights” into beacons of clarity and confidence.

1. **The “Worst” Only Means ‘Most Evil’ Lie**

One of the most persistent “check engine light” warnings in our linguistic landscape stems from a narrow understanding of what “worst” truly encapsulates. Many people, when they hear or use the word “worst,” immediately gravitate towards its most dramatic definition: “most evil” or “wicked.” While “worst” certainly can describe “bad or ill in the highest, greatest, or most extreme degree” in a moral sense, believing this is its *only* application is a significant misconception that severely limits its utility and precision. It’s like assuming your check engine light only comes on for engine failure, ignoring the myriad other, often simpler, reasons.

The dictionary provides a much richer and more expansive panorama of what “worst” can signify. It describes “worst” as being “most faulty or unsatisfactory: the worst job I’ve ever seen,” or simply “most unpleasant, unattractive, or disagreeable.” Consider “the worst personality I’ve ever known” or a “worst movie,” which is merely “poorest quality or most unpleasant to watch.” These uses highlight practical or subjective deficiencies, not necessarily ethical ones.

Furthermore, “worst” can denote inefficiency or lack of skill, as in “least efficient or skilled: The worst drivers in the country come from that state.” It also covers conditions like “most unfavorable or injurious” or being “in the poorest condition: the worst house on the block.” By limiting “worst” to only the “most evil” interpretation, we curtail our ability to accurately describe a multitude of situations where something is simply at its lowest or most undesirable point across various practical or sensory measures.

Read more about: Your Ultimate Guide to the 15 Best States for Off-Roading and Unrestricted Public Land Access

2. **The “Worst” Is Just an Adjective Lie**

Here’s another common linguistic pitfall: the assumption that “worst” functions exclusively as an adjective. This misconception is akin to thinking a car battery’s only job is to start the engine, ignoring its role in powering various electronic systems. While “worst” is undeniably a powerful superlative adjective, limiting our understanding to this single grammatical role overlooks its significant versatility and several other legitimate applications within the English language.

The truth is, “worst” can wear multiple grammatical hats. Beyond its role as an adjective, it also functions as a noun, an adverb, and even a verb. Each of these roles carries distinct implications and allows for different kinds of expression, adding layers of nuance to our communication. To ignore these alternative uses is to operate with a diminished linguistic toolkit, potentially leading to misinterpretation.

As a noun, “worst” often appears with the definite article, as in “the worst.” The dictionary explicitly states, “n. [ uncountable; usually: the + ~ ] usually: the something that is worst: Prepare for the worst.” It also serves as an adverb, typically meaning “in the worst manner” or “in the greatest degree,” as in “My sore leg hurts worst when it’s cold.” Perhaps most surprisingly, “worst” can be a transitive verb meaning “to defeat; beat,” as in “He worsted him easily.”

Read more about: Deconstructing Failure: Understanding ‘Worst’ in Business and Celebrity Ventures

3. **The “Badder” and “Baddest” Are Standard Lie**

Just as you wouldn’t use premium fuel in a diesel engine, you shouldn’t assume that every adjective forms its comparative and superlative degrees regularly. One common linguistic “check engine light” is the belief that “badder” and “baddest” are standard, grammatically correct comparative and superlative forms of “bad.” This is a widespread misconception, particularly in informal speech, and it’s crucial for clarity to understand why these forms are considered nonstandard.

The English language has numerous irregular adjectives that don’t follow the simple “-er” and “-est” rules for comparison; “bad” is a prime example. Its comparative form is “worse,” and its superlative form is “worst.” The dictionary explicitly notes this: “bad1 /bæd/ USA pronunciation adj., worse/wɜrs/ USA pronunciation worst /wɜrst/ USA pronunciation.” This is the established, conventional usage, honed over centuries.

The usage notes further reinforce this point, stating unequivocally: “The comparative badder (for worse) and superlative baddest (for worst) derived from the positive bad are nonstandard.” This means that while you might hear “badder” or “baddest” in casual conversation, they do not conform to standard English grammar in formal writing or speech. Employing them in contexts where precision is expected can lead to a perception of error or a lack of linguistic sophistication.

Read more about: The Ultimate Guide to ‘Worse’ vs. ‘Worst’: 14 Common Traps You Can’t Afford to Ignore

4. **The “Worser” Is Acceptable Lie**

Continuing our diagnostic scan of linguistic “check engine light” errors, we encounter another common mistake: the belief that “worser” is an acceptable comparative form. This “lie” is particularly insidious because it involves a correct root word (“worse”) but then incorrectly applies a comparative suffix to it, creating a grammatical redundancy. It’s like putting too much oil in your engine—it’s a good component, but too much of it actually causes problems.

“Worse” itself is already the comparative form of “bad” and “ill.” It means “more bad” or “more ill.” The error in “worser” comes from treating “worse” as if it were a positive adjective and then trying to form a comparative from it by adding “-er,” creating a double comparative that is grammatically incorrect in standard English. The dictionary’s usage notes explicitly address this, stating: “The comparative worser is also nonstandard.”

Using “worser” can often be seen as a sign of linguistic uncertainty, a common “malfunction” in the communication system. It indicates a lack of familiarity with the irregular forms that some of our most basic adjectives take. For clear, precise, and grammatically sound communication, it is imperative to remember that “worse” already holds the comparative meaning. There is no need for “worser,” and recognizing this “lie” elevates the quality of one’s language.

5. **The “Worstest” and “Worstestest” Are Always Serious Lie**

When you encounter unusual sounds from your car, you typically assume they’re serious. However, sometimes those sounds are just quirks, or even intentional, if humorous, additions. Similarly, another linguistic “lie” is the notion that forms like “worstest” and “worstestest” are always grievous grammatical errors, indicative of a severe lack of education. While they are indeed nonstandard, their presence in language isn’t always a sign of a critical malfunction; sometimes, it’s a deliberate act of playful exaggeration.

The dictionary clarifies the status of these hyper-superlatives. In its usage notes, it states: “Worst may be further inflected to form the two additional superlatives worstest (nonstandard) and worstestest (informal, humorous).” This is a crucial distinction. “Nonstandard” means they don’t conform to established rules, but “informal, humorous” tells us these forms have a specific, acknowledged role, even if outside strict grammar.

When someone says “That was the worstest movie ever,” they are usually not trying to be grammatically correct but are using exaggeration to emphasize extreme dislike in a lighthearted, almost self-aware way. The “lie” is not that these forms are grammatically standard, but that their use *always* signals a serious mistake. Recognizing the humorous or informal intent allows for a more nuanced interpretation, helping us differentiate between genuine errors and intentional linguistic play.

6. **The “Bad” as an Adverb is Always Wrong Lie**

Many drivers get caught up in the “always” traps of automotive advice – “always check your tires before every drive.” While good guidelines exist, absolute statements often hide nuances. The same goes for language, and a pervasive linguistic “lie” is the belief that using “bad” as an adverb is *always* wrong. While “badly” is indeed the standard adverbial form, the dictionary acknowledges specific, albeit informal, contexts where “bad” correctly functions as an adverb.

The primary adverbial role, meaning “in a bad way; incorrectly, inadequately, or unfavorably,” is universally held by “badly,” as the dictionary states: “adv. in a bad way; incorrectly, inadequately, or unfavorably: speaks French badly; a marriage that turned out badly.” This is the default setting for expressing actions performed poorly in standard English.

However, the “lie” arises when we fail to acknowledge the specific, limited, and often informal use of “bad” as an adverb. The context clearly states: “Bad as an adverb appears mainly in informal situations: He wanted it pretty bad.” Another entry similarly states: “adv. Informal. badly: He wanted it bad enough to steal it.” This indicates that while not standard for formal discourse, “bad” as an adverb isn’t an outright error in *all* circumstances; its use fits casual speech, conveying intensity in a direct, unvarnished way.

Read more about: The 12 Worst Classic Car Investments Made by 15 Celebrities

7. **The “Feel Bad” vs. “Feel Badly” Confusion Lie**

Few linguistic dilemmas spark as much debate and self-correction as the “feel bad” versus “feel badly” conundrum. This is a classic “check engine light” moment that often leaves speakers and writers second-guessing themselves, fearing they’ve made a terrible error no matter which choice they make. The “lie” here is that one is *always* wrong and the other *always* right, creating undue anxiety, when in reality, both can be acceptable depending on intended meaning and formality.

When you “feel bad,” you are describing your *state of being*, where “bad” is an adjective modifying “you.” The dictionary confirms this: “After such verbs as sound, smell, look, and taste… You look pretty bad; are you sick? … I feel bad from overeating.” In this context, “bad” refers to a state of poor health, regret, or general unpleasantness.

Conversely, “feel badly” can imply your *sense of touch* is impaired, as “badly” functions as an adverb modifying the verb “feel.” However, the dictionary also notes: “After the copulative verb feel, the adjective badly in reference to physical or emotional states is also used and is standard, although bad is more common in formal writing: I feel bad from overeating. She felt badly about her friend’s misfortune.” This indicates both are often acceptable for emotional/physical states, with “bad” preferred in formal writing for those senses.

Just as understanding the full range of signals from your car’s diagnostic system empowers you to make informed decisions, comprehending the complete linguistic toolkit of “worst,” “bad,” and “ill” will dramatically improve your communication. We’ve debunked some of the most common “check engine light” fears in the first section; now, let’s continue to decode more intricate linguistic mysteries. By understanding these next seven “lies,” you’ll gain even greater precision and confidence in navigating the complexities of English.

Read more about: The 12 Worst Classic Car Investments Made by 15 Celebrities

8. **The “Worst” is Never a Verb Lie**

Many drivers might think of their vehicle’s engine solely in terms of its primary function: propulsion. Yet, modern engines are complex systems with many less obvious, but equally legitimate, components and capabilities. Similarly, while most people are familiar with “worst” as an adjective or an adverb, a persistent linguistic “lie” is the belief that “worst” never functions as a verb, or that such usage is archaic or simply incorrect.

However, the truth is that “worst” can indeed act as a transitive verb. The dictionary explicitly states its verbal function: “v. [ ~ + object ] to defeat; beat.” This means you can actively “worst” someone or something, indicating a clear victory or overcoming. A straightforward example provided is, “He worsted him easily.”

Recognizing this less common, but perfectly valid, application adds another dimension to your command of the language. It transforms a perceived grammatical error into a precise, if somewhat formal, expression of dominance or triumph. Dispelling this “lie” ensures your linguistic engine is firing on all cylinders, capable of more diverse and nuanced expressions.

Read more about: Beyond the Hashtag: 12 Crucial Things Psychologists Say You Should Always Keep Private for Your Well-being

9. **The “At Worst” Implies Guaranteed Failure Lie**

When a diagnostic tool indicates a potential issue, it’s easy to jump to the most catastrophic conclusion. “At worst, the engine will seize!” This kind of overreaction mirrors a common linguistic “lie” surrounding the idiom “at worst.” Many speakers assume “at worst” implies an inevitable, severely negative outcome, almost a prophecy of guaranteed failure.

In reality, “at worst” serves as a crucial qualifier, preparing for a potential, rather than certain, undesirable scenario. The dictionary clarifies its meaning as “Idioms at (the) worst, under the worst conditions.” It also provides the definition, “at worst, if the worst happens; under the worst conditions.” An illustrative sentence is, “He will be expelled from school, at worst.”

This idiom is about considering the most unfavorable conditions *if* they were to materialize, not declaring them as a certainty. It encourages a realistic assessment of risks, allowing for preparation without succumbing to unwarranted despair. Understanding this distinction empowers you to use language that reflects thoughtful contingency planning, rather than baseless alarm.

10. **The “If Worst Comes to Worst” Is Just a Dramatic Phrase Lie**

Some drivers might dismiss a flashing warning light as merely “dramatic flair” from the car’s computer, assuming it’s an exaggeration rather than a true indicator of potential trouble. A similar linguistic “lie” exists with the idiom “if worst comes to worst,” often perceived as just a colorful, dramatic expression without a precise or practical meaning. This misconception undervalues its genuine function in planning and communication.

However, this idiom carries a very specific and critical implication: it’s about preparing for the absolute lowest point. The dictionary defines it directly: “Idioms if worst comes to worst, if the very worst happens.” An example solidifies this meaning: “If worst comes to worst, we still have some money in reserve.”

Far from being mere theatrics, “if worst comes to worst” is a pragmatic expression used to discuss contingency plans for the most extreme negative outcome imaginable. It acknowledges the possibility of a complete breakdown or disaster and prompts consideration of fallback strategies. Recognizing this exact meaning allows for precise communication when discussing serious eventualities.

Read more about: Deconstructing Failure: Understanding ‘Worst’ in Business and Celebrity Ventures

11. **The “Ill” Only Describes Sickness Lie**

Imagine a multi-purpose tool that you only ever use for one specific job, ignoring its many other capabilities. This is akin to the linguistic “lie” that “ill” primarily, or even exclusively, describes a state of poor health or sickness. While “ill” is certainly a standard adjective for unwellness, this narrow understanding overlooks a much richer and more nuanced semantic landscape within the English language.

The dictionary reveals that “ill” as an adjective extends far beyond the realm of physical ailment. It can denote hostility or unkindness, as in “hostile; unkind: [ before a noun ] ill feeling.” Furthermore, it describes something evil or wicked, seen in phrases like “evil; wicked: [ before a noun ] ill deeds.” It can also signify something unfavorable or adverse, as in “unfavorable: [ before a noun ] ill fortune.”

These broader definitions demonstrate that “ill” is a versatile descriptor for various negative qualities, not just physical health. By recognizing its capacity to describe malicious intent, moral failing, or unfortunate circumstances, you gain a more precise instrument for expressing subtle shades of negativity. Disentangling “ill” from its sole association with sickness allows for a more robust and sophisticated linguistic expression.

Read more about: From Bad to Worse (or is it Worst?): Unpacking the Ultimate Grammar Showdown

12. **The “Ill” as an Adverb is Always a Grammatical Error Lie**

Much like a mechanic might initially raise an eyebrow at an unfamiliar engine component, many people harbor the “lie” that using “ill” as an adverb is always a grammatical error, preferring “badly” in all adverbial contexts. This misconception stems from an incomplete understanding of “ill’s” full grammatical range, overlooking its legitimate, albeit often formal or specific, adverbial applications.

The dictionary clearly supports “ill” in its adverbial role, defining it as meaning “unsatisfactorily; poorly; badly: It ill befits a person to betray friends.” It also specifies its use for meaning “faultily; improperly: an ill-constructed house,” and “with difficulty or inconvenience; scarcely: an expense we can ill afford.” These examples demonstrate its proper use in formal contexts.

Furthermore, “ill” is frequently and correctly employed in compound adjectives to convey a sense of inadequacy or impropriety. The context notes: “The word ill can be used in combination with other adjectives or participles to mean ‘badly, improperly; inadequately:’ ill- + considered → ill-considered (= not thought out well in advance; inappropriate); ill- + defined → ill-defined (= not well defined or clearly set out).” Understanding these constructions is key to mastering its adverbial flexibility.

Recognizing the valid adverbial uses of “ill,” both standalone and in compounds, allows for a more refined and precise style of communication. It’s about knowing when the less common, but correct, option is the best fit for your message, proving that your linguistic knowledge goes beyond the most obvious functions.

Read more about: The 12 Grammar Mix-Ups You Voted Worst: Why These ‘Worse’ & ‘Worst’ Errors Are Best Avoided

13. **The “In the Worst Way” Always Signals Something Negative Lie**

Sometimes, a car’s warning light might indicate something that, despite the alarming phrasing, isn’t inherently negative in its practical effect, or even implies a strong desire. This counterintuitive dynamic is perfectly captured by the linguistic “lie” that the idiom “in the worst way” *always* signals a negative outcome or feeling. For many, the word “worst” automatically conjures up dread, leading to a misunderstanding of this phrase’s true, often positive, intent in informal speech.

In a fascinating twist of English idiom, “in the worst way” frequently conveys an intense positive desire or need, particularly in informal settings. The dictionary clarifies this: “Informal Terms in the worst way, in an extreme degree; very much: She wanted a new robe for Christmas in the worst way. Also, the worst way.” Another entry confirms this, stating, “Idioms in the worst way, very much; extremely: He needs praise in the worst way.”

This demonstrates that while the literal interpretation of “worst” might suggest negativity, the idiom’s established informal usage flips this meaning entirely. It’s an emphatic way to express an urgent or strong desire for something, often quite positive. To interpret it otherwise is to miss a common nuance in everyday English.

Dispelling this “lie” enables you to accurately interpret and use this idiom in casual conversation. It’s a prime example of how context and idiomatic meaning can override individual word meanings, providing a powerful, direct way to convey intense longing without implying any actual ‘worst’ outcome.

Read more about: Navigating the ‘Bad’ Spectrum: A Consumer Reports Guide to Differentiating ‘Worse’ and ‘Worst’ for Clear Communication

14. **The “Badly Off” and “In a Bad Way” Are Identical Lie**

Just as your car might have distinct warning lights for “low oil pressure” and “engine overheating,” both indicating serious problems but requiring different responses, the English language features idioms that, while similar, carry distinct nuances. A common linguistic “lie” is the belief that “badly off” and “in a bad way” are interchangeable, conveying precisely the same meaning without any differentiation. While both express negative circumstances, their specific focus and common applications vary.

“Badly off” typically refers to a state of financial or material deprivation. The dictionary states: “Idioms badly off, [ be + ~] in need of: We are quite badly off for money. not having much money; poor.” Another definition reinforces this: “Idioms bad off, in poor or distressed condition or circumstances; destitute: His family has been pretty bad off since he lost his job. Also, badly off.” It zeroes in on a lack of resources.

Conversely, “in a bad way” has a broader application, often describing severe trouble, distress, or a deteriorated state that isn’t necessarily financial. The dictionary defines it as “Idioms in a bad way, in severe trouble or distress: She’s in a bad way now.” This phrase can encompass physical illness, emotional turmoil, or general dire circumstances beyond just economic hardship.

Understanding the subtle but important distinctions between “badly off” and “in a bad way” allows for greater precision in describing a person’s unfortunate circumstances. It prevents the misuse of one phrase when the other would more accurately capture the specific nature of their distress, ensuring your language is as precise and effective as a finely tuned engine.

By methodically examining these pervasive linguistic “check engine light lies,” we hope to have provided you with the tools and knowledge to navigate the English language with greater clarity and confidence. Just as a well-understood car dashboard prevents unnecessary panic and costly mistakes, a clear grasp of these words and idioms empowers you to communicate with precision, avoiding linguistic misfires. You now have the authoritative owner’s manual for “worst,” “bad,” and “ill,” ready to drive your ideas forward with unmatched accuracy.